Abstract

Schizophrenia is a severe and heritable neuropsychiatric disorder, which arises due to a combination of common genetic variation, rare loss of function variation, and copy number variation. Functional genomic evidence has been used to identify candidate genes affected by this variation, which revealed biological pathways that may be disrupted in schizophrenia. Understanding the contributions of these pathways are critical next steps in understanding schizophrenia pathogenesis. A number of genes involved in endocytosis are implicated in schizophrenia. In this review, we explore the history of endosomal trafficking in schizophrenia and highlight new endosomal candidate genes. We explore the function of these candidate genes and hypothesize how their dysfunction may contribute to schizophrenia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a common and severe neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by both positive (delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior) and negative (diminished emotional expression or avolition) symptoms [1]. Schizophrenia affects about 0.25%–0.64% of the population of the United States [2–4]. There are negative consequences to unmanaged schizophrenia for both people with schizophrenia and their caregivers, but current therapeutics have side effects that lead some people to discontinue treatment. These facts highlight the need to elucidate specific mechanisms that underlie schizophrenia pathogenesis to develop more effective and targeted therapies.

Twin and other studies demonstrated that schizophrenia has an estimated heritability of ~80% [5]. These studies suggest that schizophrenia has a genetic component but not the source of genetic variation. Historically, candidate genes were identified from linkage studies with small sample sizes [6]. However, technological advancements have made sequencing the genomes of large numbers of people possible. These studies revealed that common variation, copy number variation (CNV), and rare loss-of-function (LoF) variation all contribute to schizophrenia. Rare LoF variation contributes a small but significant source of variation in schizophrenia, explaining about 0.274% of the overall liability [7]. Although identifying rare LoF variation has been challenging, recent progress has been made [8–10]. CNV explains about 0.85% of the variance in schizophrenia liability, and eight specific CNVs have been identified [11]. Finally, common variation explains about 3.4% of the variance in schizophrenia liability [12]. However, this variation only explains a small percentage of the overall heritability of schizophrenia, which underscores its highly polygenic and heterogenous nature. This missing heritability is most likely a result of rare variants that have not yet been identified and have much larger effects on risk [13]; larger samples sizes will certainly identify more rare variants.

Identifying candidate genes in schizophrenia

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified common variation within 145 loci associated with schizophrenia [14]. However, many of these loci are within non-coding regions of the genome, which complicates assigning affected genes to these variants. Traditionally, non-coding variants are assigned to genes based on proximity and linkage disequilibrium (LD) using multimarker analysis of genomic annotation (MAGMA). More recently, Hi-C, a method used to detect 3D chromatin structure, has been utilized to link genome wide significant (GWS) loci to genes based on a physical interaction between the GWS loci and the gene. For example, Sey et al. linked genes to variants using Hi-C datasets from human adult dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and fetal developing cortex in a process termed H-MAGMA [15].

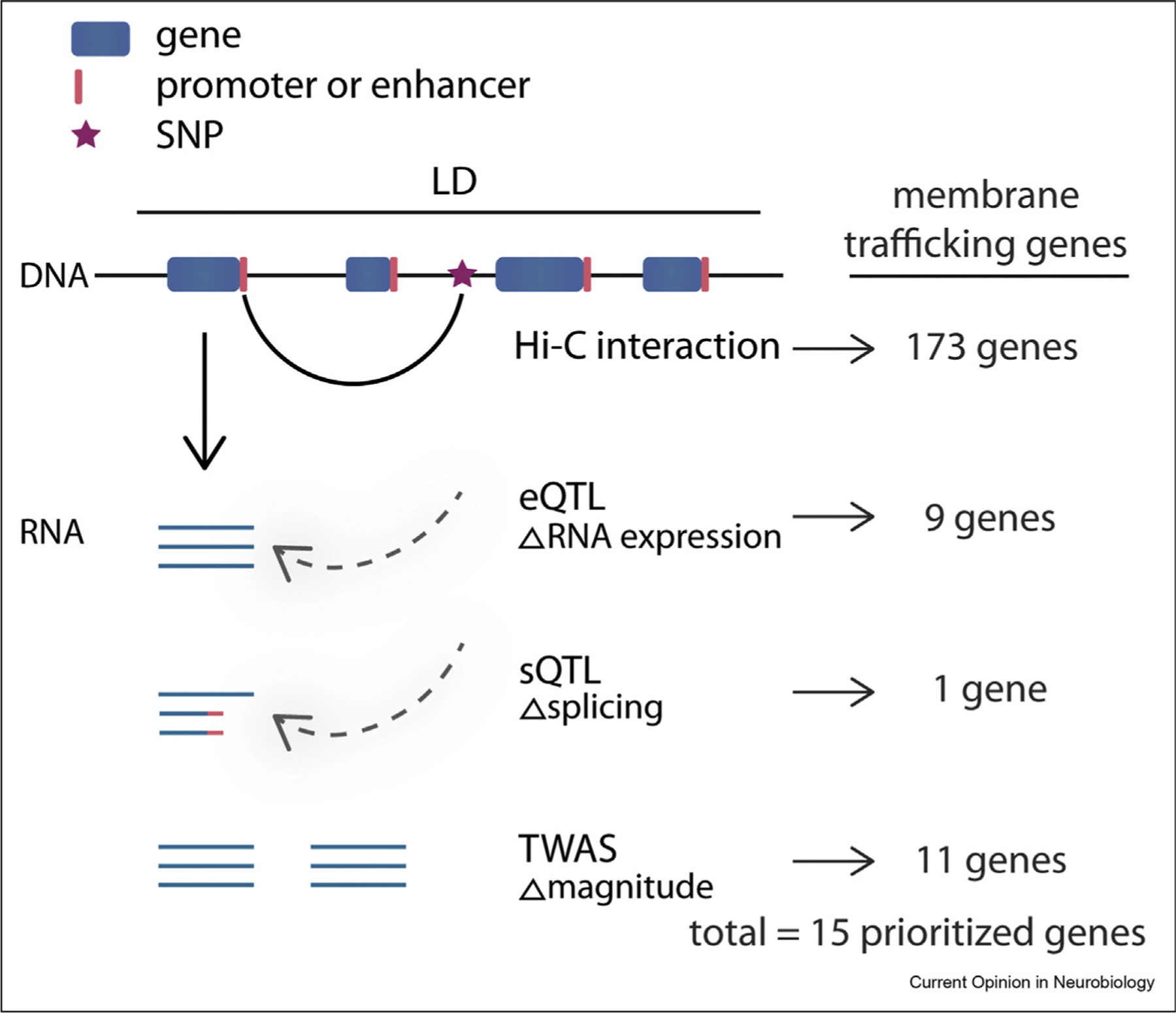

Gene candidates highlighted by H-MAGMA support a physical chromatin interaction with risk loci, but the effects of these interactions are not known. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) has been used to determine the effects of these genetic variants by quantifying how various traits, such as gene expression (eQTL) and splicing (sQTL) correlate with specific loci. Although eQTL provides support for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as the cause for expression changes of a gene, there is no consensus on how to calculate effect size, or the magnitude of the change, in gene expression. Therefore, eQTL is unreliable in determining the magnitude of gene expression changes. Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) can determine the magnitude of gene expression changes in schizophrenia. TWAS is similar to GWAS, but uses RNA-sequencing rather than DNA-sequencing, and, thus, can determine fold-changes in gene expression. These methods are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Functional genomic evidence can link candidate genes to GWS loci.

The majority of common variation in schizophrenia resides within noncoding regions of the genome, therefore, further support is needed to link a specific gene to GWS loci. Hi-C has been used to identify physical interactions between GWS loci and genes. eQTL and sQTL provide support that these GWS loci can explain gene expression and splicing changes, respectively. Finally, TWAS has been used to identify genes that are more or less expressed in people with schizophrenia than in neurotypical controls. We identified a number of membrane trafficking genes that are supported by Hi-C, eQTL, sQTL, and/or TWAS.

While these techniques provide valuable information for linking genes with GWS loci, these methods rely upon bulk Hi-C and RNA-sequencing and thus do not provide cell-type specific information. Attempting to interpret cell-type information from these data is generally biased, relying upon assumptions about cell-types by their expression of different markers, and thus may not represent the actual distribution of cell types within the brain. Therefore, single-cell RNA-sequencing is a critical next step in confidently determining which genes are affected by different GWS loci. Nonetheless, quantitative data like QTL and TWAS can provide support for specific gene candidates and affected biological pathways that lead to the cellular and physiological phenotypes in schizophrenia [16]. For example, Wang et al. integrated direct assignment, Hi–C interaction maps, QTL, and gene regulatory network data to highlight 321 “high-confidence” candidate genes (genes supported by at least two lines of evidence) for schizophrenia risk [17]. Interestingly, a number of these genes are predicted to be involved in membrane trafficking, particularly endosomal trafficking.

Endosomal trafficking was historically linked to schizophrenia

Cells contain numerous membrane-bound compartments responsible for the sorting, recycling, and degradation of protein cargo. Endocytosis transports molecules and proteins into the cell, whereas exocytosis inserts cargo into the plasma membrane and secretes cargo out of the cell. Endocytosed cargo is sorted at early endosomes. Cargo can be recycled back to the plasma membrane through rapid recycling compartments or slower recycling endosomes. Alternatively, cargo is sent to late endosomes and lysosomes for degradation. Transport carriers, including vesicles and elongated tubules, bud from and fuse with endosomes to provide both soluble and membrane-associated components to their target compartment [18].

Endosomal trafficking was implicated in schizophrenia prior to modern genomic studies. Dystrobrevin-binding protein 1 (DTNBP1), encoding the protein dysbindin-1, was linked to schizophrenia through linkage analysis [19]. Post-mortem examination suggested DTNBP1 mRNA and dysbindin-1 protein in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex was reduced in individuals with schizophrenia compared to neurotypical controls [20]. Dysbindin-1 is a subunit of the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex 1 (BLOC-1). BLOC-1 functions in the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles (LROs), such as melanosomes [21].

Despite years of effort to explore how dysfunction of dysbindin and BLOC-1 contribute to schizophrenia pathogenesis, common variants of BLOC-1 subunits were no more associated with schizophrenia than controls in genomic studies of schizophrenia [22]. Does this mean that mutations in BLOC-1 do not contribute to schizophrenia? Not necessarily; rare variants of BLOC-1 components may exist that have not yet been implicated in schizophrenia.

Endosomal trafficking is a pathway of interest in schizophrenia

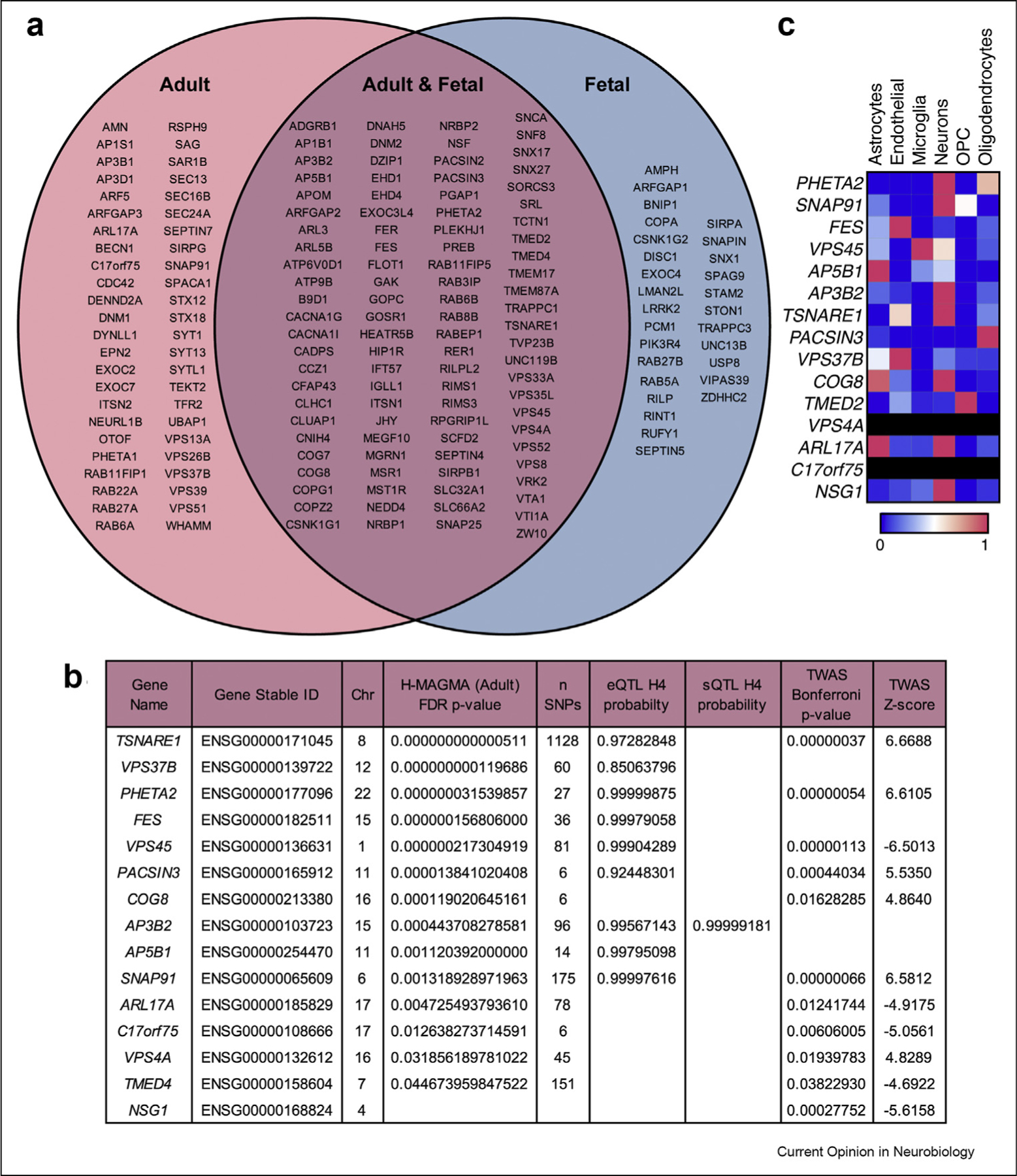

To identify membrane trafficking genes associated with schizophrenia, we compiled a list of 921 genes with gene ontology (GO) biological processes related to membrane trafficking, including both endocytic and exocytic pathways. We found 97 of 921 membrane trafficking genes were supported by both the adult and fetal H-MAGMA schizophrenia datasets. An additional 48 were supported by the adult H-MAGMA alone, and 28 were supported by the fetal H-MAGMA alone. In total, 173 genes were associated with schizophrenia GWS loci (Figure 2a). We compared the list of 921 membrane trafficking genes with eQTL and sQTL identified from adult human brain tissue [17]. We found nine genes that have significant schizophrenia-associated eQTL and 1 that has significant schizophrenia-associated sQTL. We further explored whether any membrane trafficking genes were identified in schizophrenia TWAS of human adult frontal cortex were supported by both eQTL and TWAS (TSNARE1, PHETA2, VPS45, PACSIN3, and SNAP91). These candidates are outlined in Figure 2b. While many of these candidates are considered housekeeping genes and would therefore likely be ubiquitously expressed, we wondered if any of these genes were enriched in particular cell-types in the brain. We data-mined single-cell RNA-sequencing data from human adult brain cortex [23]. The endosomal candidate genes tended to be more enriched in neurons than in glial cells (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Candidate genes involved in endosomal trafficking are well supported in schizophrenia.

(a) 173 membrane trafficking genes are supported by either fetal and/or adult H-MAGMA (FDR adjusted p-value < 0.05). (b) 15 membrane trafficking genes are supported by eQTL, sQTL, and/or TWAS (QTL = H4 posterior probability >0.7 or TWAS = Bonferroni adjusted p-value < 0.05) and are listed with their gene name, Ensembl gene stable ID, and chromosome location (chr). If these genes were supported by the adult H-MAGMA, the FDR adjusted p-value and the number of SNPs (n SNPs) associated with that gene are shown. Blank cells suggest it was not significant. (c) Within-row normalized values of transcripts per million (TPM) per candidate gene. Rows are black if there were no data for that gene. Abbreviation: oligodendrocyte precursor cell (OPC).

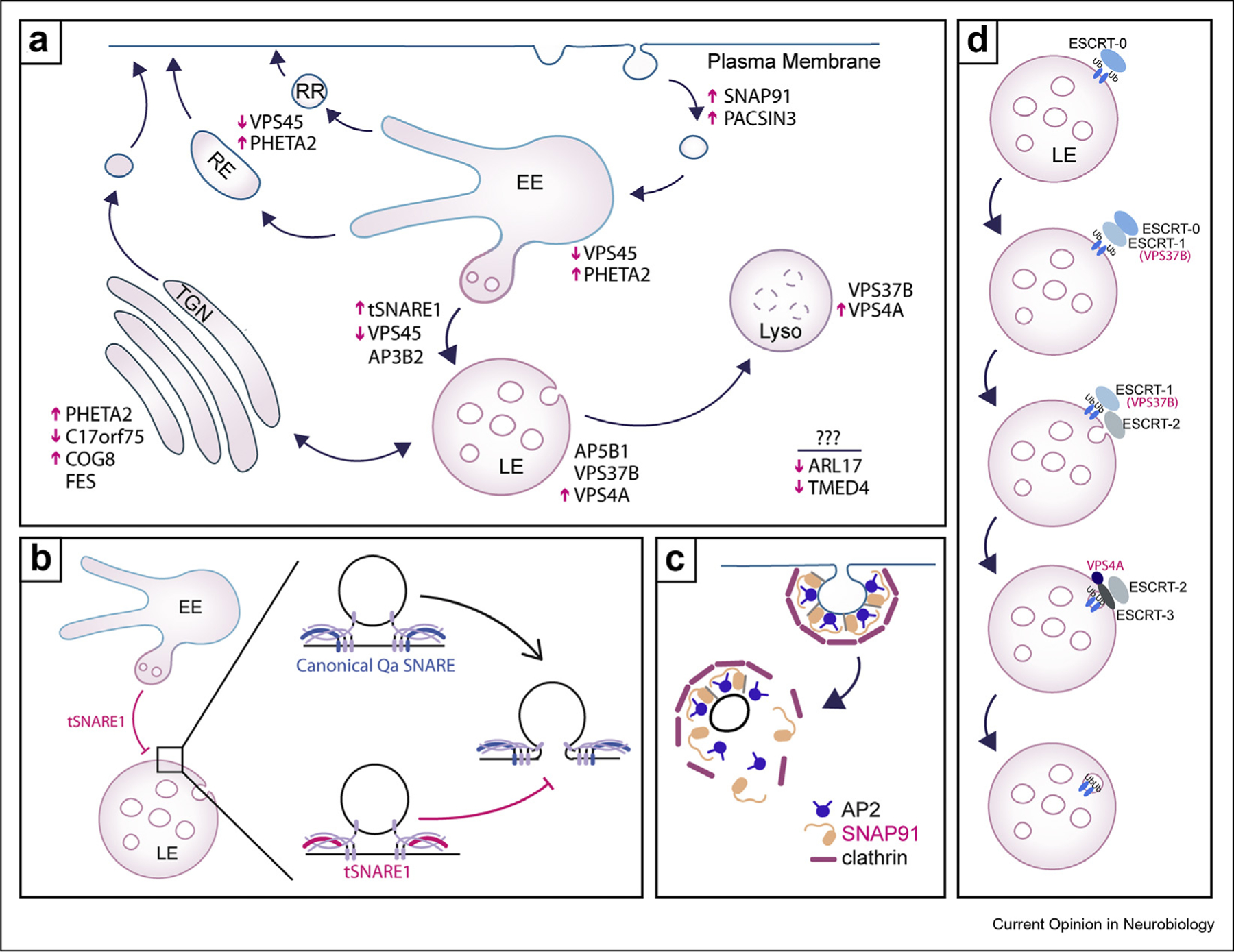

A number of prioritized genes function at the late endosome and lysosome (Figure 3a). For example, the gene that is the third most significant of the membrane trafficking genes in the adult H-MAGMA is TSNARE1. TSNARE1 is additionally supported by eQTL and TWAS, which suggests that tSNARE1 is overexpressed in schizophrenia. TSNARE1 encodes a syntaxin-like SNARE protein called t-SNARE domaining containing 1 (tSNARE1). SNARE proteins are involved in membrane fusion. We recently characterized tSNARE1 isoforms that all contain a Qa-SNARE domain. However, the majority of tSNARE1 in the brain lacks a transmembrane domain, which suggests it likely functions as an inhibitory SNARE. tSNARE1 isoforms localized primarily to the late endosome. tSNARE1 expression delayed trafficking of the somatodendritic transmembrane protein Nsg1 into late endosomes and lysosomes. Nsg1 is endocytosed from the plasma membrane and trafficked primarily from the early endosome to the late endosome and lysosome [24,25]. tSNARE1 therefore likely functions as a negative regulator to early endosome to late endosome trafficking [26] (Figure 3b). Interestingly, TWAS suggests NSG1 is downregulated in schizophrenia, although there is no evidence for a common variant being responsible for this change. In fact, NSG1 is the only gene from our list of membrane trafficking genes that was supported by TWAS but not by Hi-C or QTL.

Figure 3. Schizophrenia-associated genes function in endosomal trafficking.

(a) Overview of endocytosis and exocytosis. Schizophrenia candidate genes that are supported by at least two lines of evidence are listed according to their known localization and function. If a candidate is supported by TWAS, the magenta arrow displays whether the gene is more or less expressed in schizophrenia than in neurotypical controls. Abbreviations: early endosome (EE), late endosome (LE), lysosome (Lyso), rapid recycling (RR), recycling endosome (RE), trans-Golgi network (TGN). (b) A model by which tSNARE1 likely negatively regulates early endosome to late endosome trafficking, where the absence of its transmembrane domain blocks membrane fusion. (c) SNAP91 regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis in conjunction with AP2 and clathrin. (d) Model of how ESCRT complexes mediate late endosome intralumenal invagination.

Adaptor protein (AP) complexes are also implicated by the inclusion of AP complex subunits AP3B2 and AP5B1. AP complexes are heterotetrameric and have roles in the regulation of membrane trafficking. AP3B2 encodes a subunit of AP-3 that is specific to neurons [27]. AP-3 recognizes sorting signals on transmembrane proteins that dictate cargo be sent to lysosomes or synaptic vesicles [28]. For example, AP-3 recognizes LAMP proteins on early endosomes and directs them to late endosomes and lysosomes, thus playing critical roles in lysosomal cargo sorting [29]. Interestingly, there are significant sQTL for AP3B2 in schizophrenia, indicating that common schizophrenia variants alter the splicing of AP3B2. However, how splicing affects AP-3 neuronal expression and function is not known. AP5B1 encodes a subunit of AP-5. AP-5 localizes to late endosomes and lysosomes and is involved in a sorting step out of the late endosome [30].

SNAP91 is a gene of interest that encodes the protein SNAP91/AP180. SNAP91 is thought to function with the adaptor protein complex AP-2 in directly recruiting the v-SNARE, VAMP2, for clathrin-dependent endocytosis and recycling from the plasma membrane following exocytosis [31] (Figure 3c). At the presynapse, SNAP91 regulates the number of VAMP2 synaptic vesicles—presumably via endocytic retrieval [32]. Another prioritized candidate, PACSIN3, encodes PACSIN3 or syndaptin 3 in rodents. PACSIN3 is less studied than either PACSIN1 or PACSIN2, which have well described roles in synaptic vesicle and trans-Golgi vesicle transport. PACSIN3, however, localizes to the cell periphery and is involved in transferrin endocytosis [33], TRPV4 endocytosis [34], and glucose uptake [35].

We identified several vacuolar protein sorting (VPS) genes as candidates for schizophrenia risk: VPS4A, VPS37B, and VPS45. VPS37 and VPS4 are involved in the biogenesis of late endosomes in conjunction with endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) complexes by promoting intraluminal vesicle biogenesis (Figure 3d). Specifically, ESCRT-0 binds to ubiquitinated cargo on endosomal membranes and recruits and transfers ubiquitinated cargo to ESCRT-I. VPS37 is a subunit of the ESCRT–I complex. ESCRT-I subsequently recruits ESCRT-II, which invaginates the membrane. ESCRT-II activates ESCRT-III. ESCRT-III promotes scission of the invaginated membrane in conjunction with the ATPase VPS4 [36]. VPS4 mediates ESCRT-III subunit exchange that drives its assembly and disassembly [37]. Besides biogenesis of late endosomes, VPS4 and ESCRT-III additionally function in a number of other membrane remodeling events [36]. VPS45 is a Sec1p/Munc18-like (SM) protein that has roles in trafficking to the early endosome and recycling back to the plasma membrane [38]. More recently, VPS45 was shown to function in early to late endosome maturation [39].

PHETA2 is a candidate that encodes the protein PHETA2 (also known as FAM109B/Ses2/IPIP27B). PHETA2 interacts with OCRL, an inositol phosphatase, and localizes to early endosomes, recycling endosomes, and the trans Golgi [40]. COG8 encodes a subunit of the conserved oligomeric Golgi (COG) complex, which regulates Golgi trafficking [41]. C17orf75 encodes a largely unstudied protein C17orf75, which forms a complex with WDR11 and ICP0 and localizes to the trans-Golgi network, where it is involved in tethering of vesicles [42]. FES encodes the protein Fes, a tyrosine-protein kinase whose role in membrane trafficking is not well described but colocalizes with Golgi and endosomal markers [43]. The rest of the prioritized candidates are predicted to be involved in membrane trafficking due to sequence similarity but are not well-studied, including TMED4 and ARL17.

How might dysfunction of endocytosis and membrane trafficking contribute to schizophrenia?

Several hypotheses may explain the etiology of schizophrenia, including alterations in synaptogenesis, synaptic plasticity, synaptic pruning, and synaptic function [44–49]. The brain undergoes a period of rapid synaptogenesis after birth that peaks around 2–3 years of age, after which a period of synaptic pruning, which removes unneeded synapses, extends through late adolescence. Synapses are strengthened or weakened based on how often they are used, a process termed synaptic plasticity. Ultimately, dysregulation of the dopamine system is thought to be central to schizophrenia pathogenesis, and recent evidence suggests that alterations in the circuits that control midbrain dopamine neurons may cause this dysregulation [50].

Several lines of evidence support the idea that schizophrenia is caused by altered synaptic connectivity, particularly at the post-synapse. First, neurons are associated with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia-associated genes are enriched in neurons [15,17,51,52]. Single cell RNA-sequencing data from human samples suggest that medium spiny neurons, pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus, pyramidal cells in the somatosensory cortex, and cortical interneurons are particularly correlated with schizophrenia [53]. Second, alterations in neuronal morphology are associated with schizophrenia; for example, there a decreased density of dendritic spines is observed [54]. Third, schizophrenia associated genes are associated with GO terms related to vesicle trafficking and the post-synapse [15,17,51]. However, the exact cause of the altered synaptic connectivity in schizophrenia is not well understood.

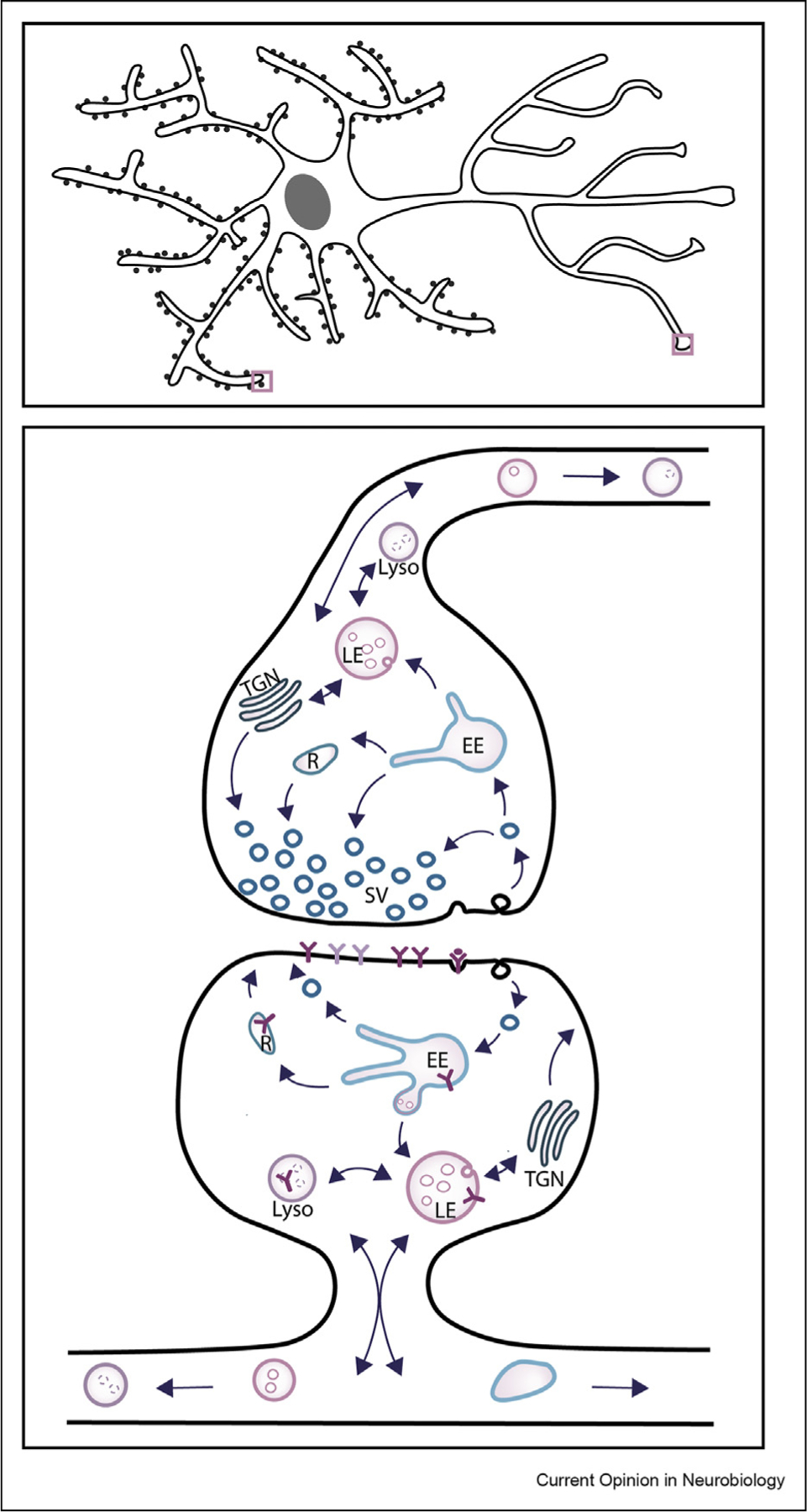

Membrane trafficking is essential for proper synaptic plasticity, pruning, and function (Figure 4). At the presynapse, the endosomal network regulates the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles, both by generating new synaptic vesicles or degrading vesicles that are damaged or unneeded. The endosomal network regulates receptor endocytosis and recycling at the postsynaptic membrane. Endosomal trafficking transports, sorts, and degrades a number of receptors at the synapse, such as AMPA receptors (AMPARs) [55,56]. The number of receptors on the post synaptic membrane dictates the strength of the excitatory or inhibitory signal that is propagated, therefore alterations in endocytic trafficking can have dramatic effects on postsynaptic function and plasticity. In line with this observation, Kim et al. optogenetically disrupted early to late endosomal trafficking and found that transient changes in the balance of endocytosis and exocytosis of AMPARs led to long-lived alterations in synaptic plasticity, presumably by sustained alterations to the ratio of receptors at the cell surface [57]. Whether degradation of these receptors occurs locally at spines or if receptors are transported to the soma for degradation is not understood. A number of studies describe polarized endosomal transport, where mature late endosomes and degradative lysosomes are localized closer to the cell body [25]. In support of local degradation at synapses, Goo et al. observed lysosomes that trafficked to the base of dendritic spines in response to activity [58].

Figure 4. Endosomal trafficking at the synapse.

A cartoon of a pyramidal neuron (top), which is a cell type associated with schizophrenia. Zoomed in region of a synapse (below) displays how endosomal trafficking plays multiple roles both at the pre- (synaptic vesicle trafficking) and post-synapse (receptor trafficking). Abbreviations: early endosome (EE), late endosome (LE), lysosome (Lyso), recycling compartments (R), trans-Golgi network (TGN), and synaptic vesicles (SV).

Endosomal trafficking is also critical for a number of developmental processes, which is another possible mechanism for schizophrenia pathogenesis. For example, proper endocytic control mediated by Rab5 and ESCRT contributes to proper axonal and dendritic thinning and pruning in Drosophila [59–61]. Dysregulation of axonal and dendritic thinning and pruning may contribute to the altered synaptic connectivity in schizophrenia. In conclusion, we have highlighted 15 schizophrenia gene candidates involved in endosomal trafficking. As endosomal trafficking is critical for processes thought to be disrupted in schizophrenia, understanding how these candidates contribute to schizophrenia pathogenesis should be further investigated.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01GM054712 to P.B., R01NS105614 and R35GM135160 to S.L.G., and F31MH116576 and T32GM119999 to M.P.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, Falloon IRH, Gagnon E, Guyer M, Howes MJ, Kendler KS, Shi L, Walters E, et al. : The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biol Psychiatr 2005, 58:668–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu EQ, Shi L, Birnbaum H, Hudson T, Kessler R: Annual prevalence of diagnosed schizophrenia in the USA: a claims data analysis approach. Psychol Med 2006, 36:1535–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J: A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med 2005, 2:e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilker R, Helenius D, Fagerlund B, Skytthe A, Christensen K, Werge TM, Nordentoft M, Glenthøj B: Heritability of schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum based on the nationwide Danish twin register. Biol Psychiatr 2018, 83:492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Coordinating Committee, Cichon S, Craddock N, Daly M, Faraone SV, Gejman PV, Kelsoe J, Lehner T, Levinson DF, Moran A, et al. : Genomewide association studies: history, rationale, and prospects for psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatr 2009, 166:540–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh T, Walters JTR, Johnstone M, Curtis D, Suvisaari J, Torniainen M, Rees E, Iyegbe C, Blackwood D, McIntosh AM, et al. : The contribution of rare variants to risk of schizophrenia in individuals with and without intellectual disability. Nat Genet 2017, 49:1167–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh T, Kurki MI, Curtis D, Purcell SM, Crooks L, McRae J, Suvisaari J, Chheda H, Blackwood D, Breen G, et al. : Rare loss-of-function variants in SETD1A are associated with schizophrenia and developmental disorders. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19: 571–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. *Zoghbi AW, Dhindsa RS, Goldberg TE, Mehralizade A, Motelow JE, Wang X, Alkelai A, Harms MB, Lieberman JA, Markx S, et al. : High-impact rare genetic variants in severe schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2021, 118. To find rare variants in schizophrenia, Zoghbi et al. selectively sequenced individuals with severe and treatment-resistant schizophrenia. By selecting those individuals with the most extreme phenotypes, the authors found the highest burden of de novo rare variants in schizophrenia to date, highlighting a potential avenue for identifying genetic variants in smaller sample sizes.

- 10. *Singh T, Neale BM, Daly MJ: Exome sequencing identifies rare coding variants in 10 genes which confer substantial risk for schizophrenia. medRxiv 2020, 10.1101/2020.09.18.20192815. In the largest exome sequencing study on schizophrenia to date, Singh et al. identify rare variation in 10 genes associated with schizophrenia. Prior to this study, only 1 gene (SETD1A) had been robustly linked with rare variation in schizophrenia.

- 11.Marshall CR, Howrigan DP, Merico D, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Wu W, Greer DS, Antaki D, Shetty A, Holmans PA, Pinto D, et al. : Contribution of copy number variants to schizophrenia from a genome-wide study of 41,321 subjects. Nat Genet 2017, 49: 27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ripke S, Neale BM, Corvin A, Walters JTR, Farh K-H, Holmans PA, Lee P, Bulik-Sullivan B, Collier DA, Huang H, et al. : Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 2014, 511:421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. * Owen MJ, Williams NM: Explaining the missing heritability of psychiatric disorders. World Psychiatr 2021, 20:294–295. In this succinct review, Owen et al. describe why variants from modern genomic studies on schizophrenia have failed to explain the majority of heritability, the so-called “missing heritability.” The authors summarize the main challenges to determining the source of this missing heritability and how studying rare variants may fill the gap.

- 14.Pardiñas AF, Holmans P, Pocklington AJ, Escott-Price V, Ripke S, Carrera N, Legge SE, Bishop S, Cameron D, Hamshere ML, et al. : Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat Genet 2018, 50:381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. **Sey NYA, Hu B, Mah W, Fauni H, McAfee JC, Rajarajan P, Brennand KJ, Akbarian S, Won H: A computational tool (H-MAGMA) for improved prediction of brain-disorder risk genes by incorporating brain chromatin interaction profiles. Nat Neurosci 2020, 23:583–593. Sey et al. developed an analysis platform called H-MAGMA, which uses Hi-C chromatin interaction profiles from human brain tissue to link disorder-associated noncoding variants from five psychiatric disorders (including schizophrenia) to their affected genes. This is a technological advancement from traditional MAGMA analysis, which maps variants to their nearest genes.

- 16. **Guan F, Ni T, Zhu W, Williams LK, Cui L-B, Li M, Tubbs J, Sham P-C, Gui H: Integrative omics of schizophrenia: from genetic determinants to clinical classification and risk prediction. Mol Psychiatr 2021, 10.1038/s41380-021-01201-2. This comprehensive review summarizes the various -omic (genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, metabolomics, connectomics, and microbiomics) studies on schizophrenia. Guan et al. particularly highlight studies that have integrated several -omic approaches, which they convincingly argue provides a roadmap to understand complex psychiatric disorders.

- 17.Wang D, Liu S, Warrell J, Won H, Shi X, Navarro FCP, Clarke D, Gu M, Emani P, Yang YT, et al. : Comprehensive functional genomic resource and integrative model for the human brain. Science 2018, 362, eaat8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkin SR, Lakoduk AM, Schmid SL: Endocytic pathways and endosomal trafficking: a primer. Wien Med Wochenschr 2016, 166:196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straub RE, Jiang Y, MacLean CJ, Ma Y, Webb BT, Myakishev MV, Harris-Kerr C, Wormley B, Sadek H, Kadambi B, et al. : Genetic variation in the 6p22.3 gene DTNBP1, the human ortholog of the mouse dysbindin gene, is associated with schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet 2002, 71:337–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weickert CS, Rothmond DA, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Straub RE: Reduced DTNBP1 (dysbindin-1) mRNA in the hippocampal formation of schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res 2008, 98: 105–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Setty SRG, Tenza D, Truschel ST, Chou E, Sviderskaya EV, Theos AC, Lamoreux ML, Di Pietro SM, Starcevic M, Bennett DC, et al. : BLOC-1 is required for cargo-specific sorting from vacuolar early endosomes toward lysosome-related organelles. Mol Biol Cell 2007, 18:768–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson EC, Border R, Melroy-Greif WE, de Leeuw CA, Ehringer MA, Keller MC: No evidence that schizophrenia candidate genes are more associated with schizophrenia than noncandidate genes. Biol Psychiatr 2017, 82:702–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darmanis S, Sloan SA, Zhang Y, Enge M, Caneda C, Shuer LM, Hayden Gephart MG, Barres BA, Quake SR: A survey of human brain transcriptome diversity at the single cell level. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015, 112:7285–7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yap CC, Digilio L, McMahon L, Winckler B: The endosomal neuronal proteins Nsg1/NEEP21 and Nsg2/P19 are itinerant, not resident proteins of dendritic endosomes. Sci Rep 2017, 7:10481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yap CC, Digilio L, McMahon LP, Garcia ADR, Winckler B: Degradation of dendritic cargos requires Rab7-dependent transport to somatic lysosomes. J Cell Biol 2018, 217: 3141–3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. **Plooster M, Rossi G, Farrell MS, McAfee JC, Bell JL, Ye M, Diering GH, Won H, Gupton SL, Brennwald P: Schizophrenia-linked protein tSNARE1 regulates endosomal trafficking in cortical neurons. J Neurosci 2021, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0556-21.2021. In our study, we characterize one of the more significant but previously unstudied gene candidates for schizophrenia risk, TSNARE1. We found that TSNARE1 encodes a SNARE protein that lacks a transmembrane domain that likely functions as a negative regulator in early endosome to late endosome trafficking.

- 27.Grabner CP, Price SD, Lysakowski A, Cahill AL, Fox AP: Regulation of large dense-core vesicle volume and neurotransmitter content mediated by adaptor protein 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci Unit States Am 2006, 103:10035–10040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullin AP, Gokhale A, Larimore J, Faundez V: Cell biology of the BLOC-1 complex subunit dysbindin, a schizophrenia susceptibility gene. Mol Neurobiol 2011, 44:53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peden AA, Oorschot V, Hesser BA, Austin CD, Scheller RH, Klumperman J: Localization of the AP-3 adaptor complex defines a novel endosomal exit site for lysosomal membrane proteins. J Cell Biol 2004, 164:1065–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirst J, Itzhak DN, Antrobus R, Borner GHH, Robinson MS: Role of the AP-5 adaptor protein complex in late endosome-to-Golgi retrieval. PLoS Biol 2018, 16, e2004411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan L-S, Moshkanbaryans L, Xue J, Graham ME: The ~ 16 kDa C-terminal sequence of clathrin assembly protein AP180 is essential for efficient clathrin binding. PLoS One 2014, 9, e110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koo SJ, Kochlamazashvili G, Rost B, Puchkov D, Gimber N, Lehmann M, Tadeus G, Schmoranzer J, Rosenmund C, Haucke V, et al. : Vesicular synaptobrevin/VAMP2 levels guarded by AP180 control efficient neurotransmission. Neuron 2015, 88:330–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Modregger J, Ritter B, Witter B, Paulsson M, Plomann M: All three PACSIN isoforms bind to endocytic proteins and inhibit endocytosis. J Cell Sci 2000, 113 Pt 24:4511–4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’hoedt D, Owsianik G, Prenen J, Cuajungco MP, Grimm C, Heller S, Voets T, Nilius B: Stimulus-specific modulation of the cation channel TRPV4 by PACSIN 3. J Biol Chem 2008, 283: 6272–6280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roach W, Plomann M: PACSIN3 overexpression increases adipocyte glucose transport through GLUT1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007, 355:745–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vietri M, Radulovic M, Stenmark H: The many functions of ESCRTs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21:25–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37. *Pfitzner A-K, Mercier V, Jiang X, Moser von Filseck J, Baum B, Šarić A, Roux A: An ESCRT-III polymerization sequence drives membrane deformation and fission. Cell 2020, 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.021. Using elegant in vitro reconstitution assays, Pfitzner et al. elucidate the precise molecular events that lead to sequential ESCRT-III polymerization at the membrane, finding that Vps4 drives ESCRT-III subunit exchange that leads to membrane deformation.

- 38.Rahajeng J, Caplan S, Naslavsky N: Common and distinct roles for the binding partners Rabenosyn-5 and Vps45 in the regulation of endocytic trafficking in mammalian cells. Exp Cell Res 2010, 316:859–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frey L, Ziętara N, Łyszkiewicz M, Marquardt B, Mizoguchi Y, Linder MI, Liu Y, Giesert F, Wurst W, Dahlhoff M, et al. : Mammalian VPS45 orchestrates trafficking through the endosomal system. Blood 2021, 137:1932–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noakes CJ, Lee G, Lowe M: The PH domain proteins IPIP27A and B link OCRL1 to receptor recycling in the endocytic pathway. Mol Biol Cell 2011, 22:606–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ungar D, Oka T, Brittle EE, Vasile E, Lupashin VV, Chatterton JE, Heuser JE, Krieger M, Waters MG: Characterization of a mammalian Golgi-localized protein complex, COG, that is required for normal Golgi morphology and function. J Cell Biol 2002, 157:405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Navarro Negredo P, Edgar JR, Manna PT, Antrobus R, Robinson MS: The WDR11 complex facilitates the tethering of AP-1-derived vesicles. Nat Commun 2018, 9:596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zirngibl R, Schulze D, Mirski SE, Cole SP, Greer PA: Subcellular localization analysis of the closely related Fps/Fes and Fer protein-tyrosine kinases suggests a distinct role for Fps/Fes in vesicular trafficking. Exp Cell Res 2001, 266:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kahn RS, Sommer IE, Murray RM, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR, Cannon TD, O’Donovan M, Correll CU, Kane JM, Van Os J, et al. : Schizophrenia. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2015, 1: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smeland OB, Frei O, Dale AM, Andreassen OA: The polygenic architecture of schizophrenia - rethinking pathogenesis and nosology. Nat Rev Neurol 2020, 16:366–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCutcheon RA, Reis Marques T, Howes OD: Schizophrenia-an Overview. JAMA Psychiatr 2020, 77:201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boksa P: Abnormal synaptic pruning in schizophrenia: urban myth or reality? J Psychiatry Neurosci 2012, 37:75–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zagorski N: New evidence for classic “synaptic pruning” hypothesis of schizophrenia. Psychiatr News 2016, 51:1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi-Takagi A, Barker P, Arika S: Readdressing synaptic pruning theory for schizophrenia. Commun Integr Biol 2014, 4: 211–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sonnenschein SF, Gomes FV, Grace AA: Dysregulation of midbrain dopamine system and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatr 2020, 11:613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gandal MJ, Zhang P, Hadjimichael E, Walker RL, Chen C, Liu S, Won H, van Bakel H, Varghese M, Wang Y, et al. : Transcriptome-wide isoform-level dysregulation in ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Science 2018, 362, eaat8127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. **Mah W, Won H: The three-dimensional landscape of the genome in human brain tissue unveils regulatory mechanisms leading to schizophrenia risk. Schizophr Res 2019, 10.1016/j.schres.2019.03.007. In this review, Mah et al. discuss how Hi-C and QTL can be used to identify gene candidates from genomic studies on schizophrenia. Using this method, Mah et al. highlight a set of gene candidates in schizophrenia supported by Hi-C and summarize how these may contribute to schizophrenia pathogenesis.

- 53.Skene NG, Bryois J, Bakken TE, Breen G, Crowley JJ, Gaspar HA, Giusti-Rodríguez P, Hodge RD, Miller JA, Muñoz-Manchado AB, et al. : Genetic identification of brain cell types underlying schizophrenia. Nat Genet 2018, 50:825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glausier JR, Lewis DA: Dendritic spine pathology in schizophrenia. Neuroscience 2013, 251:90–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrini EM, Lu J, Cognet L, Lounis B, Ehlers MD, Choquet D: Endocytic trafficking and recycling maintain a pool of mobile surface AMPA receptors required for synaptic potentiation. Neuron 2009, 63:92–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsuda S, Kakegawa W, Budisantoso T, Nomura T, Kohda K, Yuzaki M: Stargazin regulates AMPA receptor trafficking through adaptor protein complexes during long-term depression. Nat Commun 2013, 4:2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim T, Yamamoto Y, Tanaka-Yamamoto K: Timely regulated sorting from early to late endosomes is required to maintain cerebellar long-term depression. Nat Commun 2017, 8:401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goo MS, Sancho L, Slepak N, Boassa D, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Bloodgood BL, Patrick GN: Activity-dependent trafficking of lysosomes in dendrites and dendritic spines. J Cell Biol 2017, 23: 201704068–201712513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Issman-Zecharya N, Schuldiner O: The PI3K class III complex promotes axon pruning by downregulating a Ptc-derived signal via endosome-lysosomal degradation. Dev Cell 2014, 31:461–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang H, Wang Y, Wong JJL, Lim K-L, Liou Y-C, Wang H, Yu F: Endocytic pathways downregulate the L1-type cell adhesion molecule neuroglian to promote dendrite pruning in Drosophila. Dev Cell 2014, 30:463–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanamori T, Yoshino J, Yasunaga K-I, Dairyo Y, Emoto K: Local endocytosis triggers dendritic thinning and pruning in Drosophila sensory neurons. Nat Commun 2015, 6:6515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]