Abstract

Background

Trials involving adults who lack capacity to consent encounter a range of ethical and methodological challenges, resulting in these populations frequently being excluded from research. Currently, there is little evidence regarding the nature and extent of these challenges, nor strategies to improve the design and conduct of such trials. This qualitative study explored researchers’ and healthcare professionals’ experiences of the barriers and facilitators to conducting trials involving adults lacking capacity to consent.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted remotely with 26 researchers and healthcare professionals with experience in a range of roles, trial populations and settings across the UK. Data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

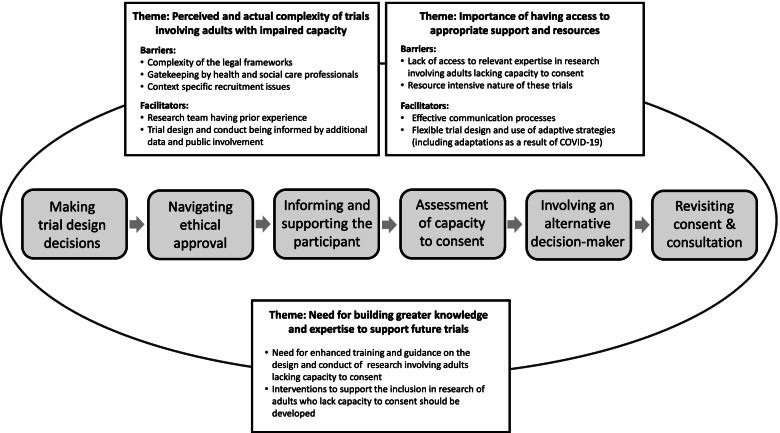

A number of inter-related barriers and facilitators were identified and mapped against key trial processes including during trial design decisions, navigating ethical approval, assessing capacity, identifying and involving alternative decision-makers and when revisiting consent. Three themes were identified: (1) the perceived and actual complexity of trials involving adults lacking capacity, (2) importance of having access to appropriate support and resources and (3) need for building greater knowledge and expertise to support future trials. Barriers to trials included the complexity of the legal frameworks, the role of gatekeepers, a lack of access to expertise and training, and the resource-intensive nature of these trials. The ability to conduct trials was facilitated by having prior experience with these populations, effective communication between research teams, public involvement contributions, and the availability of additional data to inform the trial. Participants also identified a range of context-specific recruitment issues and highlighted the importance of ‘designing in’ flexibility and the use of adaptive strategies which were especially important for trials during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants identified a need for better training and support.

Conclusions

Researchers encountered a number of barriers, including both generic and context or population-specific challenges, which may be reinforced by wider factors such as resource limitations and knowledge deficits. Greater access to expertise and training, and the development of supportive interventions and tailored guidance, is urgently needed in order to build research capacity in this area and facilitate the successful delivery of trials involving this under-served population.

Keywords: Informed consent, Mental capacity, Randomised controlled trials, Inclusion, Under-served populations, Qualitative

Background

An estimated two million people in England and Wales have significantly impaired decision-making, which may be due to acute medical events, or through long-term conditions affecting cognitive function such as dementia and mental illness, or associated with learning disabilities or at the end of life [1]. Up to half of patients in acute medical and psychiatric healthcare settings lack decision-making capacity [2, 3], and this rises to around 70% in settings such as care homes [4] and 90% in critical care [5]. Research into conditions affecting these groups, who often experience higher care needs and require greater health resource use [6], is vital. However, adults with impaired decision-making and who therefore have an impaired ability to provide their own consent, are often excluded from research [7–9]. This exclusion is a result of the complex ethical and practical challenges encountered when seeking to include adults who lack capacity in research and the daunting range of methodological, structural and systemic barriers to their inclusion [10].

Impact of exclusion from trials for this under-served population

Despite a growing emphasis on making trials more inclusive to under-represented or under-served populations, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) INCLUDE initiative [11], few trials are designed to include participants who lack capacity, and the numbers of participants unable to consent who are actually recruited are worryingly low [12]. This exclusion is particularly concerning in conditions where the prevalence of cognitive impairment is high. For example, 1 in 3 patients with a hip fractures have concomitant cognitive impairment, yet this population is excluded or ignored in 8 out of 10 hip fracture trials [13]. Consent-based recruitment biases have a clear impact on the generalisability of trials, as demonstrated in a trial in acute haemorrhagic shock (CONTROL) where the consent model used reduced enrolment by 80–90% in the USA and led to a trial population that was not representative of the intended target population and the trial being halted due to futility [14]. This widespread exclusion of adults lacking capacity results in a poorer evidence base for their treatment and care compared to other groups, leading to ‘evidence biased’ care [15] and contributing to the health inequalities many already experience [16].

COVID-19 has shone a spotlight on this issue through the disproportionate impact on populations who are under-served by research, many of whom have impaired capacity to consent. Dementia is an age-independent risk factor for contracting COVID-19, subsequently requiring hospitalisation, and death [17], with older people living in care homes at particularly high risk [18]. However, a review of COVID-19 trials found that half excluded older people, with other relevant indirect exclusions such as cognitive impairment [19]. Older people were excluded from all of the vaccine trials included in the review [19]. This has led to criticisms that, despite the disproportionate impact on people living in care homes, the research community has largely ignored this population when conducting clinical research on COVID-19 [20]. Similarly, people with learning disabilities with COVID-19 were five times more likely to be admitted to hospital and eight times more likely to die than people without a learning disability [21]. Yet, prior to the pandemic, 90% of RCTs were designed in a way that excludes people with a learning disability [7].

Ethical and legal complexities of trials including adults who lack capacity to consent

Trials involving adults with impaired capacity to consent are recognised as being ethically and legally complex, with the need to ensure that special safeguards are in place to protect the interests of this group [22]. The legal arrangements for including adults who lack capacity vary by jurisdiction and the type of research in question. In the UK, clinical trials of investigational medicinal products (CTIMPs) are governed by the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trial) Regulations which permits a legal representative to give consent on behalf of an adult who lacks capacity [23]. However, other types of research (including trials not classified as CTIMPs) are governed by mental capacity legislation with different laws in place across the UK [15]. There are important differences between how non-CTIMPs involving adults who lack capacity, particularly in emergency situations, are governed. For example, where the treatment needs to be given as a matter of urgency and it is not possible to obtain either the participant’s consent or to consult a family member or carer before participation, in England and Wales the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) permits recruitment into the study if it is done in accordance with a protocol previously approved by a research ethics committee (REC) [24]. However, in Scotland, there are no similar provisions under the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act (AWI) [25] and so such research cannot be lawfully carried out in Scotland [22]. Unsurprisingly, these complexities have resulted in misunderstandings about the legal frameworks and how they apply to research involving adults lacking capacity [26], which then translates into incomplete and misinterpreted information provided to legal representatives and consultees [27]. This in turn contributes to the decisional and emotional burden experienced by family members acting as legal representatives and consultees [28].

In the UK, other safeguards designed to protect this group considered ‘vulnerable’ include the requirement for the research to be approved by an appropriate body, which is one of the panel of national RECs that are flagged to review studies involving adults unable to consent for themselves [29]. Trials in populations, settings and conditions where capacity to consent is of particular relevance require careful design, planning and implementation to incorporate these important safeguards whilst ensuring that these populations have the opportunity to contribute to and benefit from research.

Importance of understanding and addressing the barriers to inclusion

Strategies to improve the conduct of trials involving adults who lack capacity will not be effective unless the barriers are recognised and addressed. In recent years, there has been a huge focus on improving trial conduct through initiatives such as Trial Forge [30] and by the MRC-NIHR Trials Methodology Research Partnership (formerly Methodology Hubs) [31] in the UK, and the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative in the US [32]. Considerable work has also been undertaken to identify and address the priority areas for research into recruitment and retention in trials [33]. However, these ambitious programmes have almost exclusively concerned trials involving adults who provide their own consent to research. Given the considerable additional complexities in trials involving adults who are unable to provide consent, similarly large-scale work is needed to ensure that these populations are better served by research.

This qualitative study marks the first step to empirically explore the barriers and facilitators to conducting trials with adults who lack capacity to consent in the UK across a range of populations and settings, and to identify potential areas for future research and interventions to support their inclusion. The objectives of the study were to explore researchers’ and healthcare professionals’ views about the barriers and facilitators to research involving adults lacking capacity to consent and to establish their training, education and support needs for designing and conducting research with these populations.

Methods

We conducted remote semi-structured interviews with researchers in health and social care and healthcare professionals who design and conduct research with adults who lack capacity.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited through UK-wide research networks (e.g. MRC-NIHR TMRP, UK Trial Managers’ Network (UKTMN)) who disseminated information about the study to their members, and via social media (e.g. Twitter). The aim of the interviews was to obtain a range of views and experiences, and so maximum variation sampling was used to ensure the inclusion of participants with diverse roles and experiences. This heterogeneity enabled an understanding of variations in experiences whilst also investigating core elements and shared issues [34].

Participants were iteratively selected to take part in an interview based on criteria used to construct the sample frame such as their role (e.g. Trial Managers, Research Nurses, Chief Investigators and other members of research team), experience with populations and conditions (e.g. dementia, frailty, COVID, trauma, learning disability, stroke), research settings (e.g. ICU, acute care, community, care homes), types of study/intervention (e.g. CTIMPs, surgery, complex intervention) and stage of the trial (e.g. completed, recently commenced, requiring adaptions during COVID-19). As this is the first study in this area, the lack of a clear understanding about the range of experiences meant that an iterative approach to sampling was warranted, where analysis of initial data influenced subsequent recruitment decisions [34]. Eligibility was assessed by email discussion with potential participants about their role and experiences, and eligible participants were then invited to take part in a single one-to-one interview by telephone or online (via Zoom video conferencing).

Ethical considerations

This study was reviewed by the Cardiff University School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (SMREC ref. 21.28) and received a favourable opinion. Prior to agreeing to take part in an interview, participants were provided with a participant information sheet and consent form by email and given the opportunity to ask questions. All study participants provided verbal consent prior to participation which was audio recorded. This approach is in accordance with the Health Research Authority (HRA) guidance that consent may be obtained orally (or by any other means of communication) for research studies that are not clinical trials [35]. Participants were allocated a unique study ID to ensure anonymity of participants, and all trial names and other identifying features were removed from transcripts prior to analysis to ensure anonymity of the trials discussed.

Data collection

The topic guide for the interviews was developed by the research team and was informed by previous research [10]. It was piloted with two researchers with similar roles to participants. The guide was used to help structure the interview, although the exact phrasing of questions and sequence of areas of enquiry was not intended to be rigidly adhered to and participants were openly encouraged to talk about other areas and experiences that they felt were relevant to the topic. Notes were made during the interviews to highlight significant points for further discussion and researcher observations were recorded in order to capture any contextual data. Participants were also provided with information about a decision support tool that has been developed by the research team [36] and asked for their views about conducting a trial to establish its effectiveness using SWAT (Study Within a Trial) methodology [37], and how it might be implemented in practice. Data relating to this topic area are not included in this paper but will be reported separately.

Data collection took place between April and June 2021. Recruitment and data collection continued until the research team considered that sufficient data (defined as the depth, diversity, and adequacy of the data) were obtained to answer the research questions [38]. A total of 26 interviews were conducted with researchers and healthcare professionals, of which 25 interviews were conducted by video conferencing (Zoom) and one by telephone. All interviews were conducted by the first author, who is female and a nurse by profession and is experienced in conducting qualitative research. The interviews were digitally audiorecorded with consent. The mean duration of the interviews was 45 min (range 34–56 min).

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by an external professional transcription service who have previously been used by the research team. The transcripts were checked by the first author for accuracy and completeness against the source data and anonymised. Thematic analysis of the interviews was undertaken through a process of familiarisation with the data, data coding, generation of initial themes, and refining the themes [39]. Qualitative data analysis software (NVivo 12, QRS International) was used to support data analysis. Transcripts were read and re-read by the first author to achieve familiarity, and data were iteratively coded using codes derived from the data, and those identified a priori. Data generation and analysis was undertaken concurrently to facilitate an iterative approach to coding and identification of early initial themes. Analysis of the first four interview transcripts was undertaken by the first author, and then discussed with the wider research team to review the coding framework and coding process. The remaining transcripts were then iteratively coded by the first author with a second researcher (a medical sociologist with extensive experience in qualitative research) reviewing the coding of a subset of transcripts (n=4), selected to represent a range of different researcher roles, to enable greater critical reflexivity in the analytical process [40] and ensure coding validity. In accordance with reflexive thematic analysis, a statistical ‘inter-rater reliability’ approach to coding validity was not used [41]. Initial themes were generated by the first author and then developed and refined through an iterative process of discussions about data interpretation by the research team, before then finalising these themes.

Results

Participants consisted of four Chief Investigators (CI), ten Trial Managers (TM) or Senior Trial Managers (STM), four Research Nurse/Practitioners or Senior Research Nurses and two non-clinical researchers who recruited participants, two qualitative researchers and four who had other roles such as a CTU manager (see Table 1). In terms of trial settings, their experiences ranged from trials in acute or emergency settings such as critical care, pre-hospital, and emergency departments (ED), to primary care and care homes. Trial populations included people living with long-term conditions such as dementia and mental health conditions, people receiving palliative care and people with learning disabilities, as well as acute events such as trauma, stroke, cardiac arrest and myocardial infarction. Trial interventions included a range of CTIMPs, as well as non-CTIMPs including complex interventions and surgical trials. Due to the timing of the interviews (mid 2021), many participants had recently experienced designing and conducting COVID-19 trials or reported their experiences of the impact of COVID-19 on trials which had been designed and set up pre-pandemic.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| No. of participants (n=26) |

|

|---|---|

| Role | |

| Chief Investigator/Principal Investigator | 4 |

| Trial Manager/Project Manager | 4 |

| Senior Trial Manager/Programme Manager | 6 |

| Research Nurse/Research Practitioner | 2 |

| Senior Research Nurse/Team Lead | 2 |

| Qualitative Researcher | 2 |

| Research Associate/Senior Research Associate (recruiting participants) | 2 |

| Other (e.g. statistician, Clinical Trials Unit manager, research governance lead) | 4 |

| Experience in role | |

| 0–4 years | 6 |

| 5–9 years | 10 |

| 10+ years | 10 |

| Location | |

| England | 24 |

| Scotland | 2 |

Participants described a wide range of experiences with previous and ongoing trials involving adults who lack capacity to consent and reported how a number of factors influenced various key processes throughout the design, conduct and delivery of a trial (see Table 2). These processes can be categorised as making trial design decisions, navigating ethical approval for the trial, providing information to and supporting decision-making by potential participants with impaired capacity, undertaking assessment of capacity to consent, the involvement of alternative decision-makers (consultees and legal representatives), and revisiting consent and consultation throughout the trial.

Table 2.

Key processes in the the design, conduct and delivery of trials involving adults with impaired capacity

| Process | Description of process |

|---|---|

| Making trial design decisions | Decisions about the design of the trial made prospectively (e.g. eligibility criteria) and during the ongoing conduct of the trial (e.g. adaptations following a feasibility study) |

| Navigating ethical approval | Process of seeking review by a Research Ethics Committee and the challenges of obtaining a favourable opinion. May involve multiple approvals process across the UK nations and beyond for multi-centre multi-national trials |

| Informing and supporting the participant | Providing information about the trial to a potential participant with a communication disability and/or impaired capacity, and supporting their involvement in making a decision about participation |

| Assessment of capacity to consent | Assessment of a person’s mental capacity with respect to their ability to make a decision about participating in a trial, in accordance with the process set out in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 or other devolved legislation |

| Involvement of alternative decision-maker | Process of identifying and consulting an alternative decision-maker (e.g. consultee or legal representative) on behalf of a participant who lacks capacity to consent. In accordance with the legal frameworks, this may involve someone acting in either a personal or professional capacity |

| Revisiting consent and consultation | Informed consent is an ongoing process which may require revisiting consent and/or consultation with alternative decision-makers due to changes in the participant’s capacity during the trial. This includes in emergency research where a participant may have been recruited without prior consent or consultation |

Participants described a number of inter-related barriers and facilitators, of which the main contributors are outlined below using anonymised illustrative quotations and are summarised in Table 3 below. Three over-arching themes were identified: (1) the perceived and actual complexity of trials involving adults with impaired capacity, (2) the importance of having access to support and resources and (3) the need for building a body of knowledge and expertise to support future trials. The diagram in Fig. 1 shows the themes and related barriers and facilitators.

Table 3.

Summary of barriers and facilitators to conducting trials involving adults with impaired capacity

| Process | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Making trial design decisions |

∙ Complexity of the legal frameworks governing trials involving adults lacking capacity ∙ Lack of access to relevant expertise in trial teams ∙ Lack of effective training and information about conducting trials with adults who lack capacity ∙ Context-specific recruitment issues (e.g. lack of consultees/legal representative in some settings, role of gatekeepers) ∙ Pressure of recruitment targets and timescales which do not take account of the additional time required to recruit adults lacking capacity ∙ Lack of resources (e.g. research nurse time) to meet the additional resources required ∙ Lack of appropriate and agreed outcome measures for participants with cognitive impairment and their proxies |

∙ Experience and familiarity with trials with adults lacking capacity to consent ∙ Availability of additional data (qualitative, feasibility) to inform the design and conduct of the trial ∙ Flexibility and use of adaptive strategies (e.g. allowing remote contact and consent from consultees and legal representatives) ∙ Feedback from funders and reviewers which recognises the importance of the inclusion of adults lacking capacity and supports their inclusion |

| Navigating ethical approval |

∙ Lack of knowledge and understanding by RECs and research teams about the legal provisions for adults lacking capacity and how they are implemented in practice ∙ Differences in the legal provisions between nations (e.g. between England & Wales and Scotland) and the impact of dual applications and multiple sets of trial documents ∙ Lack of provision for conducting emergency non-CTIMP research in Scotland under AWI ∙ Inconsistency in REC reviews (both between and within RECs) and inaccuracies in advice/requirements |

∙ Having an established relationship with a REC who have previously reviewed trials involving adults who lack capacity by the research team ∙ Effective communication with RECs who are able to offer knowledgeable advice to trial teams |

| Informing and supporting the participant |

∙ Complex and lengthy Participant Information Sheets that are not cognitively or linguistically accessible ∙ Lack of access to timely translation services that are appropriate for people with cognitive impairment who do not have English as a first language |

∙ Availability of accessible trial information (e.g. easy-read, pictorial, brief summary version) ∙ Involvement of family and carers to support the person with cognitive impairment to make a decision about research participation |

| Assessment of capacity to consent |

∙ Requirement to conduct assess capacity remotely which is more challenging and unfamiliar ∙ Lack of access to background information held in clinical records |

∙ Seeking the views of others who are familiar with the person (e.g. family, usual carers) ∙ Access to expertise on communication and assessing capacity (e.g. Speech & Language Therapist) |

| Involvement of alternative decision-maker |

∙ Reliance on care team to identify and approach family members ∙ Gatekeeping or lack of engagement from families and care team ∙ Uncertainty around the legal and ethical role of alternative decision-makers ∙ Challenging process of decision-making when the person’s wishes and preferences are unknown |

∙ Flexible consent arrangements (e.g. telephone consultation, verbal consent/agreement) ∙ Established processes for involving alternative decision-makers (e.g. prospective list of care team members able and willing to act as consultee/legal representative) |

| Revisiting consent and consultation |

∙ Participant is discharged, transferred or dies before consent can be sought (e.g. deferred consent or recovered capacity) ∙ Reliance on remote contact only during a trial (e.g. postal follow-up only) |

∙ Regular communication and establishing a rapport with the participant and their care team ∙ Prospective planning for changes in capacity (e.g. prospectively obtaining family contact details, ongoing involvement of family/carer) |

Key: REC research ethics committee, CTIMP clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product, AWI Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the barriers and facilitators to conducting trials involving adults lacking capacity to consent

Perceived and actual complexity of trials involving adults with impaired capacity

Complexity of the legal frameworks

Participants’ experiences of the complexity of the legal frameworks governing trials involving adults lacking capacity, and the perceived complexity by those without direct experience, acted as a barrier to the design and conduct of trials. This included the difference between the frameworks governing CTIMP and non-CTIMP studies, the implications for who could be involved as an alternative decision-maker, the legal basis for their decision, and the different terminology used. However, having experience across different types of trials reduced the complexity for some researchers.

It is quite complicated because the rules change depending on whether it’s a drug trial or whatever. There’s consultees or legal representatives and they’re slightly different even though they’re more or less the same thing. The legalities of it are quite complex but I think once you’ve got your head around it, because I see it all the time and I do it all the time it’s relatively easy for me, whereas for a researcher who’s maybe doing this for the first time, it’s not so much. [ID 01, research governance lead].

Participants described trials involving adults lacking capacity as a minefield, and many expressed fears that consent might be obtained from the ‘wrong person’. This trepidation was a particular concern when research staff had less experience in research with adults lacking capacity, where family circumstances were not straightforward, where professionals were acting as a consultee or legal representative, or where consent pathways were more complex. These fears centred around the legal and professional implications of unintentional non-compliance with the legal frameworks. For some, this impacted on how trial design decisions were made in relation to selecting eligibility criteria which led to the subsequent exclusion of adults lacking capacity such as those with learning disabilities or dementia as the safest default position. Where this occurred, participants acknowledged the problematic nature of this exclusion.

As a researcher it feels like just an insurmountable black box of horrendousness that I dare not go [into]. It feels very much [that] if you get this wrong you will be illegal … and the ethics police will come for you or something. So, we just try and avoid it and then I’m not really sure that that’s the right thing. It’s scary. [ID 02, care home researcher]

The differing legal frameworks across the UK, EU and beyond acted as a barrier to conducting multi-centre trials. This was particularly encountered in emergency non-CTIMP research which is not currently permitted in Scotland, and so trials were either unable to include Scottish sites or they had to amend the trial design to have different recruitment pathways in Scotland which aligned with the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act [25]. Other participants reported that their trials that did not reach the definition of being emergency research but were ‘borderline’ cases with narrow recruitment windows or were being conducted in emergency settings, and so also encountered problems through being on the legal ‘cusp’. This demonstrated that the legal dichotomy that exists between emergency and non-emergency research was much less clearly defined in practice.

The complexity surrounding the legal frameworks also contributed to the challenges of navigating ethics review for these trials. Participants reported it being often a difficult process and sometimes a ‘brutal’ or ‘baptism of fire’ experience. This included situations where RECs raised concerns about the processes being proposed, although researchers considered that they had adhered to the legal frameworks to the best of their ability to interpret the requirements. REC concerns sometimes centred on who would act as a consultee or legal representative, particularly where they had a dual role as a carer and so potentially may indirectly benefit from the intervention.

The REC had a problem with that consultee being the carer of the individual because they felt that consultee advice wouldn’t be that impartial and we included data collection from carers. So, we had to try and separate that out, and that’s quite difficult because when you’re looking for a consultee, the nearest person to that individual is likely to be their carer and that is the person that is likely to know them best. So, it’s a bit of a double-edged sword, isn’t it? [ID 04, research programme manager]

Participants also reported inconsistencies in ethics reviews, with conflicting advice being provided both between different RECs and from the same REC regarding different studies. Some participants reported receiving inaccurate advice from RECs which they felt obliged to follow in order to obtain the favourable opinion that they needed, despite knowing the information to be inconsistent with the legal frameworks.

I remember myself and the project lead going to the ethics meeting and being grilled about who would take on the role of the personal consultee and [the REC] being adamant that it needed to be the lasting power of attorney for health and welfare, which it doesn’t need to be, which I did try to say but they weren’t really having any of it. So, [we] dutifully we put in the protocol that we have to firstly approach a lasting power of attorney if there is one in place, but if not or if not suitable then we will speak to another member of the family or another friend. So, we’ve kind of had to follow that approach which feels inappropriate really but that was imposed by ethics. [ID 06, trial manager]

There were particular challenges when navigating ethical approval for emergency research conducted without prior consent or consultation (often termed deferred consent). This was illustrated in a pre-hospital cardiac arrest trial where questions around the ability of members of the public to ‘opt out’ of the trial were raised by the REC, although this could potentially lead to delays in administering life-saving treatment.

They thought it was important that people could let us know that they didn’t want to be in the trial, and I think that it was a misguided piece of advice. So, we did it and we opened recruitment and no one got in contact with us to say, ‘can you please put me on the register?’ because nobody knows when someone might go into cardiac arrest. So, I think it’s a burden on the researchers, without any really meaningful outcome. If you check the peoples’ name against some register and say there were a hundred names on the register, it means the paramedics are going to have to pause while they do recruitment to assess if they should recruit, randomise this person. It’s not safe and makes the research unethical. [ID 23, senior trial manager]

Research nurses were less likely to share trial teams’ concerns about the complexity of the legal frameworks or the need for more information. They were generally satisfied that they were complying with the legal frameworks if they complied with the approach that was stated in the protocol. This was partly influenced by their perception about where responsibilities lay, but also because they worked across multiple trials to recruit a range of participants in high pressure environments and so needed straightforward processes to follow.

We are all assuming, rightly or wrongly, that these things have been dealt with by the MHRA and all the legal groups. I think it’s something that needs to be handled by the trial centre … we do need to query these things, but I think if it was all done at the beginning, and it was all set up and we don’t have to worry about it and there was a document that came in the introduction part of the trial, then that’s as much as we would need to know in my opinion. [ID 24, research nurse]

Benefit of having prior experience

Participants frequently reported how members of the team having relevant prior experience acted as a facilitator. This included having clinically trained researchers who were familiar with cognitive impairment and issues around capacity either as investigators on the trial or located within the Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), as well as CTU staff who had prior experience with conducting trials involving adults who lacked capacity. However, while some participants were members of teams or located within centres with considerable expertise in this area, many reported a more ad hoc nature of having access to people with relevant experience due to the relative rarity of such trials. Of particular value was their practical experience of the application of the legal frameworks and an understanding of mental capacity assessment processes.

Not a lot of studies that come through even our unit have had to go down the route of dealing with capacity and so forth. But, actually, although you’re aware of regulations, it’s never until you really need to apply them that you start to learn the ‘ins and outs’, is it? [ID 22, senior trial manager]

Having experience within trials teams also increased their confidence in designing trials to include adults who lacked capacity, partly due to a lack of information and support available from elsewhere.

It was really difficult to get anything concrete that was useful. And that’s where my colleague would come in because I would have been very reluctant to have proposed this without [their] expertise of being an ex-GP. [ID 26, Chief Investigator]

Research nurses also described the benefit of having experience in the same clinical area or population that they were conducting trials in, which increased their confidence in recruiting participants who lacked capacity. Where research nurses lacked personal experience, they drew on other team members’ experience, and having a team with a mixture of clinical backgrounds was seen as advantageous.

Gatekeeping by health and social care professionals

In addition to the role gatekeepers can play in research generally, participants described the additional layer of gatekeeping that can occur for people with cognitive impairment in a wide range of settings including in mental health, older people and in care homes.

We have a lot of care coordinators who go oh no, my patients are just not well enough, they wouldn’t be interested in that, they’re not well enough, you know, it’s not something that would be appropriate to talk to them about. [ID 01, research governance lead]

I think consent and capacity to consent in care homes is quite a tricky issue, because you do have these gatekeepers along the way as well. They’ve got another layer with the care home staff there, that’s quite difficult. [ID 04, research programme manager]

In some situations, participants reported how the involvement of alternative agencies introduced additional gatekeeping barriers, especially when these groups would not be considered to hold any decision-making authority according to the legal frameworks. This sometimes led to considerable delays.

You identify that someone might be eligible, and you want to get them involved, and not spend months and months contacting every relative. And, we did have a few cases [when] we needed to have a social services meeting to decide whether the person can take part. Some of them went on about two or three months, and then the nurses are just waiting for a decision on how to move forward with the patient. [ID 20, senior trial manager]

Gatekeeping was perceived by participants as being paternalistic, recognising that health and social care staff intended to protect those in their care from the perceived burdens and harms that they associated with research. Participants suggested that further work to integrate care and research was needed, and more education and awareness about research and about the importance and justification to include people with impaired capacity in research in order to generate the evidence to inform their care.

Trial design and conduct being informed by additional data and public involvement

The importance of having access to additional data when designing and conducting trials involving adults with impaired capacity was highlighted by a number of researchers. This included feasibility studies which provided estimates of the number of potential participants who might lack capacity, allowed the feasibility and acceptability of consent models to be assessed, and enabled processes for identifying and seeking agreement or consent from alternative decision-makers to be explored. It also enabled trial teams to understand how often there might not be a family member to act as a consultee or legal representative for participants who would therefore require a nominated consultee or professional legal representative to be identified instead. Data collection processes and completion rates could also be assessed, including where proxy-reported data were being provided by carers or family members, which could then be amended for the main trial if need be.

Some participants described the value of having qualitative data to directly inform the design and conduct of a trial. This was gained through either a qualitative study being embedded during a feasibility study or in the main trial, or formed part of a process evaluation. In some cases, qualitative interviews exploring participants’, clinicians, and carers’ experiences of recruitment raised unanticipated concerns about participants’ capacity to consent at the time of enrolment which led to these issues being raised with trial managers and clinical staff involved in recruitment. Providing this feedback synchronously, rather than waiting for the formal qualitative analysis that followed, provided an opportunity to revise consent arrangements and revisit site staff training on capacity and consent in real time.

Qualitative research in the context of the trials highlights issues that you wouldn’t find if you didn’t do it. Because we would have taken that consent and assumed everything was fine and it’s only because I did those interviews and I had that relationship with [the trial manager], that we were able to kind of iron out some of these things and try and do something about it. Otherwise, I think we would have just assumed all was okay. [ID 12, qualitative researcher]

Researchers who had experienced the value of concurrent qualitative research described how they would purposefully design future trials in these populations to include qualitative research focusing on aspects of consent and capacity during trial recruitment, with early findings reported to inform trial conduct.

Public involvement was also reported to have a facilitative effect through a number of different mechanisms. At the early design and funding application stages, lay research partner support for including people with impaired capacity was seen as crucial for the trial. During the ethics review process, it strengthened the ethical justification for their inclusion, and also ensured that trial materials were appropriately worded and accessibly designed for both people with cognitive impairment and their families.

Our Chair for that [public involvement] group was a stroke survivor and they were also involved in the Ethics application and went to the Ethics Committee …. I think that certainly was helpful for [the REC members] to know that we’ve involved patients in not only the patient facing documentation, but also in the discussions involving people without capacity and yes, they would have wanted to be involved, and believed [their spouse] would have made that decision for them if they had been asked. [ID 21, trial manager]

Context-specific recruitment issues

Whilst many of the barriers and facilitators were generic across trials and populations, a number of participants reported context-specific issues. This included the impact from a lack of research staff in less research active areas such as community-based services, or where clinical and research roles had to be combined such as paramedics attending a call, or settings outside the NHS such as care homes. Even areas with high research activity such as primary care encountered challenges recruiting people with impaired capacity as they often relied on recruitment methods such as screening patient records and sending out invitations which these populations are unlikely to be able to respond to. Clinical pathways which involved transition between care settings such as discharge from hospital to community follow-up, often encountered challenges around maintaining contact and continuity of data collection with patients who were unable to self-report.

Where trials used postal recruitment and data collection methods, there were particular challenges around interpreting non-responses or assessing capacity. It was also difficult to recruit people with fluctuating or borderline capacity who lived alone but required consultee or legal representative involvement—or which may be required during the duration of the trial if capacity were to be lost.

Quite often our participants live independently at home or semi independently. It's quite difficult to track down a carer in a lot of instances so even trying to get hold of a consultee is quite difficult for the researchers. First of all, you have to get the potential participant to name somebody and then getting the contact information for them and then trying to track them down has got issues of its own. [ID 04, research programme manager]

Depending on the nature of the intervention, some trials tried to overcome these challenges by sending the initial recruitment invitation addressed to the household, or including a statement in the initial invitation or questionnaire in which the person could indicate that they had problems with their memory or understanding, or they recruited through registries such as NIHR Join Dementia Research [42] which includes an option for a person’s representative to be contacted about a study.

Trials that recruited care home residents who lacked capacity encountered specific challenges around relying on busy care home staff to assist with determining eligibility, approaching care home residents on behalf of the researchers and informing mental capacity assessments. They also played a key role in contacting family members to act as a consultee or legal representative, data collection, monitoring and reporting changes in residents’ condition (including capacity to provide ongoing consent) and potentially delivering the intervention and reporting compliance/adherence. In addition to their gatekeeping role, these additional roles added to the complexity of trials in care homes as the staff may lack the time or motivation to take on these additional roles on top of an already heavy workload.

In other contexts, trials with short time windows for recruitment were very challenging as they required a compressed process for capacity assessment and identification of alternative decision-maker if required. This included trials in ED and ICU settings, as well as those involving trauma where there were additional pressures of recruiting within expected surgical timeframes against the backdrop of operating list timings. These trials might also involve randomisation to surgical or non-surgical management where clinician equipoise and patient/family preferences could strongly influence recruitment. There were also additional challenges around surgeons’ views about the requirements for capacity to consent to research as opposed to their usual consent practices for treatment decisions, and where cognitive impairment associated with the traumatic event such as a hip fracture following a fall may be superimposed on existing cognitive issues due to a condition such as dementia.

The argument that we often got back was, “Well, this isn’t different to what we were doing with routine practice.” But our start has always been, “But it isn’t the same as routine practice, because you’re asking someone to take part in a trial.” [ID 12, qualitative researcher]

Another important context was the nature of the intervention and whether it was designed to enable participants with cognitive impairment to engage with it. This was particularly challenging when potential participants might have physical disabilities or hearing and vision impairments in addition to cognitive and or communication impairment, for example in conditions such as a stroke. Additional linguistic complexities may also arise if English is not the person’s first language. These issues were often difficult to untangle and were sometimes conflated by researchers, trial recruiters and RECs. Participants highlighted the importance of exploring the feasibility of implementing the intervention in these different contexts, in addition to the feasibility of the consent and consultation arrangements.

Issues around data collection and the lack of validated questionnaires for these populations was also cited as a barrier to conducting trials, as well as a lack of consensus around which outcome measures should be used. Some researchers described the additional challenges this would bring in terms of the impact on data analysis.

There was definitely a lot of thought in that trial about which questionnaires were appropriate to be completed by a proxy, if there were validated proxy versions of those questionnaires, and if there weren’t, what was the most appropriate wording for us to use? There were questionnaires that we did remove because we thought that it wasn’t really appropriate for someone else to answer that on their behalf. That will definitely have an impact in the analysis side of things, because we’ll have a lot of missing data on those. [ID 05, trial statistician]

In one study, rather than using formal interviews to collect qualitative data with care home residents with cognitive impairment, the researchers reported the use of ‘in the moment conversations’ to capture their views and feelings about the intervention. These conversations would be recorded in the form of written notes by the researchers, rather than being audio or video recorded. This was seen as a pragmatic way of including the voices of a population which has high levels of cognitive impairment where formal interviews were unlikely to provide in-depth or ‘quality’ data.

Research teams also described the importance of recording and reporting the use of supportive and adaptive strategies in different contexts, such as including a question about whether participants had researcher support to complete their questionnaires whether they had capacity or not. They also highlighted the importance of contemporaneously recording the data collection methods used at each timepoint because in these populations the person who was providing data might change over time.

And just recording that whole process - being able to record who’s actually completing that questionnaire, is it a proxy or not? And making sure that we have those at all of the different time points, as it might not be the same for the whole trial. [ID 05, trial statistician]

Importance of having access to support and resources

Lack of access to relevant expertise

Where trial teams did not have relevant internal experience, the lack of access to external expertise was reported to be a considerable barrier. Some participants described the difference that having a knowledgeable ‘colleague down the corridor’ would make if available, and this lack of access to expertise ultimately impacted on their confidence and ability to design trials that included adults lacking capacity.

We did not have any particular expertise in our research team and institute, you know someone who can advise us on okay, if you want to involve people who lack capacity this is what you should do, this is how you need to write the ethics approval, this is how you should just carry it out. So, we just had no idea how to do it. [ID 02, care home researcher]

Participants also expressed a desire to have input from sources of expertise such as the HRA when they were navigating the contextualised intricacies of designing trials involving adults lacking capacity against a backdrop of the complexities of the legal frameworks. Analogies were drawn with the ability to consult the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for scientific advice at any stage during the development of a CTIMP trial [43]. Some participants reported the impact of not being able to seek advice from ‘flagged’ NHS REC with expertise in reviewing research involving adults who lack capacity ahead of submitting their application for ethics review as their input was only accessible once an application had been submitted. Other participants described how trials that excluded adults who lacked capacity would be reviewed by a REC that was not necessarily experienced in reviewing research involving adults lacking capacity and therefore they were unable to benefit in terms of potentially increasing the inclusivity in their current trial or to inform their design of future trials.

Resource-intensive nature of trials including adults with impaired capacity

Trial setup was frequently reported to be prolonged for trials involving adults lacking capacity due to additional delays associated with preparing alternative forms of documents and for gaining ethical approvals. In addition to standard participant information sheets (PIS) and consent forms, trials including adults lacking capacity had to create versions of the PIS for consultees and legal representatives, and an alternative consent form or consultee declaration form. Some trials used the same version for both personal and nominated/professional consultees and legal representatives, whilst others developed separate versions. Some trials also created accessible information for participants with cognitive impairments (e.g. brief summary, pictorial or easy-read versions, video format). The development and document control aspects of multiple documents required additional resources, particularly to ensure that effective public involvement was undertaken, and where versions translated into other languages were also being used.

[A trial] where maybe you need only two information sheets, it is quicker. But for this, I think last time we probably submitted about ten or twelve different information sheets, and you want to consult with different people, you want more time to consult with not just a lay group, you probably want to consult with [care home] residents and with staff and with relatives. So, there’s a lot of work to do to do it properly I think which we’d probably skimp on because we just don’t have the time. [ID 06, trial manager]

However, it was the additional delays around ethical approval, particularly where there were sites in Scotland as well as England and Wales that was reported to have the greatest impact. Again, this was adversely affected by a lack of expertise in conducting these trials.

We have tried to maintain the same protocol across both nations because I thought at the outset that that might be easier. With hindsight it probably wasn’t but the advice wasn’t there when we set off, so we had to just do what we felt would work. Essentially, we've got a different IRAS number for the capacity elements of the study in Scotland and not the rest of it, and we almost have two complete document sets now. [ID 17, trial manager]

The dual ethical approval processes meant that applications were reviewed sequentially—in England and Wales and then Scotland where only one NHS REC reviews research involving adults who lack capacity—which impacted on opening sites and potentially having to re-submit documents where one REC required changes but not the other.

So that in itself was quite tricky because for a while we had ethical approval in one country, but we didn’t have it in the other and then if we had any amendments they had to go separately and then we had to wait. [ID 20, senior trial manager]

Differences included terminology and who could act as an alternative decision-maker, as well as processes of establishing if a participant lacked capacity to consent. For example, in Scotland, certificates of incapacity are issued under the AWI [25], and so protocols and context-specific site training needed to take account of these differences. Some trials reported having very high numbers of different consent and information documents. Where trials involved emergency situations, it became even more complex, with accompanying additional uncertainties over timescales.

Scotland have slightly different guidelines again, so we’ve had to kind of model pathways that are as universal as possible but representing the differences. But obviously, there is the worry that they may disagree with our process, in which case you’ve then got to go back and potentially start that process again, you know, in terms of protocol and so on. [ID 22, senior trial manager]

It also led to knock on delays such as database development which was already complex due to the array of forms required, multiple addresses (participant, consultee) to be stored, and potential changes to data collection (self-report, proxy completed) over time.

The additional resources needed to recruit adults with cognitive impairments were also highlighted by participants. This included the additional time needed to provide information about the trial to the person with the cognitive impairment, and to check their understanding which in turn might lead to the need for an assessment of their capacity to consent.

It’s knowing that sometimes you have to take time with patients to be able to absorb the information. So, it’s not always a straightforward you can go and complete a consent form with someone. It might be that you go back and forth a few times to allow them to retain the information that they need about the trial. I mean it’s expected but sometimes, you know, we are under pressure to recruit a lot of the time. [ID 16, research team lead]

Assessing whether a participant had capacity to consent to the trial required additional time and also necessitated having trained and experienced personnel to appropriately conduct assessments. This was viewed as particularly challenging in populations where capacity fluctuated and for interventional trials which required complex information to be understood. Only a few participants reported having a specific process to follow in a trial. Some described the use of cognitive tests such as Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to inform their capacity assessment when the test was already being used in the trial, or applying the principles of the MCA to conduct an assessment. Although some reported the challenges of assessing capacity.

So, I found it very difficult, if not impossible, for me, as a researcher, to be able to assess their capacity. I mean I’ve never done any kind of formal mini mental state exams or anything like that. Any kind of formal capacity assessment other than following the principles of the Act… so I go by those principles rather a kind of battery of tests which I know that other people have done. [ID 02, care home researcher]

Others described using the judgement of colleagues who may have been more experienced in assessing capacity or with this population, or the person’s usual care team who may have been more familiar with the person, which all took additional time. As the assessment was often recorded on study-specific forms in addition to the person’s clinical care records, additional trial documents were needed.

Having assessed a potential participant as lacking capacity to consent, recruiting staff then needed to identify and approach someone to act as a personal consultee or legal representative. This was considered to be the most resource-intensive part of recruiting adults lacking capacity. In non-emergency trials recruiting in secondary care settings this was generally more straightforward, although it may still have required multiple attempts to contact a family member. However, it was especially time-consuming in settings where family members may not be available or are not in close contact such as in care homes, or where there was little way of contacting families such as remote recruitment in primary care. Even once a family member had been identified, there were issues around non-responses that led to uncertainties about whether the family member had received the information, was not willing to act as consultee or legal representative, or if this should be interpreted as a passive form of declining participation on the person’s behalf. This led to potential participants being left in a ‘state of limbo’.

I may have gone out [to the potential participant’s home] and realised that that person may need a personal consultee, but there wasn’t anyone that they lived with, a spouse or anyone, or a family member in the home. So, I would then often leave the personal consultee information and I would write my name and number on it and sometimes I would get contacted, other times I wouldn’t. But then you don’t know whether that information’s been seen, or acted on, or whatever. [ID 08, researcher in older people]

If no family member or close friend could be identified, an additional process was needed to identify and approach someone in a professional capacity to act as a consultee or legal representative. This could be a member of the person’s usual care team, e.g. the doctor responsible for their care or a member of care home staff, provided they were not involved in the trial.

We kind of go down the route of trying to identify a [care home resident’s] family member or friend to start with, and in most cases, there would be somebody that we can send information to initially. We would send information out to them, give them a couple of weeks to contact us or to send back their agreement form, and then we’d send out a chase, and then if we hadn’t heard anything another seven days after that, then we’d go down the route of identifying a nominated consultee. [ID 06, trial manager]

In some care homes, a suitable member of the care team would be identified once a consultee or legal representative was needed, in others it was a pre-delegated and one member of the care team would take on this role for all residents if needed. Not all care homes or staff were comfortable with this process however, and some required additional explanation and reassurance or did not wish to use this approach in their care home. In secondary care settings, some research nurses reported having prospectively created a pool of colleagues to act as potential consultees or legal representatives which facilitated the process. This sometimes took the form of a log that was maintained by the research nurse and was considered particularly useful in time-sensitive trials such as those involving trauma. It was viewed by some as a way for clinical staff to get involved in supporting research without the requirements of GCP training. It was reported that some felt reassured that it was an interim arrangement as consent would later be sought from the patient or their family, although there was no guidance or support for this role in any of the trials.

They know that it’s only a finite consent that they’re giving because the next step will be either the participant themselves if they agree [when] gaining capacity, or the relative. And the professional consultee [sic] only stands if the patient dies. [ID 13, research nurse]

Participants also acknowledged the additional time required for collecting data and completing outcome measures both with participants with cognitive impairment and when proxy reported.

Obviously a lot of them are having to sit down and fill out measures with staff, it’s not just handing out, you know, if you were doing a trial in an adult population, or something, you just give them a load of questionnaires to fill out themselves and it just doesn’t work like that for studies where you’ve got to get staff to do proxy measures, or you’re getting self-report from people with dementia, you’re having to sit down with them to do that. [ID 15, Chief Investigator]

These resource implications and the need to meet expected or metric-driven recruitment rates sometimes resulted in participants feeling under pressure to recruit more quickly or to find alternatives to including participants with impaired capacity.

Oh, you’ve only recruited such and such an amount? Like what’s the delay can you not just move it on? I think with this population things take longer, and recruitment takes longer, there’s more people involved, there’s extra things to be sensitive, mindful about. Yeah, wouldn’t it be easier if we could just talk to their parents or talk to their support workers and get their answers, but just because something’s easy doesn’t mean it should be that way. [ID 03, learning disabilities researcher]

Having adequate support and resources was seen as a key facilitator, and some participants described how their experiences had led them to build in additional resources when developing funding applications, beyond those usually available through R&D departments or clinical research networks.

We funded a half–time research nurse at every site because of the difficulties in working with these patients and their families, and the sorts of visits that were needed, going out to their homes. It was quite intensive so that was funded on the grant. [ID 20, senior trial manager]

However, the competitiveness of funding applications that need to be seen as offering value for money alongside other trials with populations which are more straightforward to recruit was a significant challenge. Participants also reported the challenges of having caps for particular funding schemes, e.g. the tiers in NIHR Research for Social Care (RfSC) and Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) programmes, which did not take account of these additional resource requirements. This was particularly the case where the research was conducted in non-NHS settings such as care homes and so did not have equitable access to research delivery infrastructure.

The challenges of pressure to conduct more inclusive trials, with limited funding and resources available to adequately support inclusion, were also highlighted as a barrier to both conducting trials involving adults lacking capacity and other under-served populations in general.

Sometimes you have to bear in mind you need to get the numbers, but you also need to think about inclusivity with that …. I don’t think resources is the reason not to do it, but it’s got to be a consideration. You know, you can’t ask for the world and not fund it. [ID 12, qualitative researcher]

The role of funders and grant reviewers in encouraging inclusive research was welcomed; however, the responsibility to conduct more inclusive trials was viewed as being shared between funders, RECs and research teams.

Applications where you force people to think about how [they] have they addressed inclusivity and then also being willing to provide funds to support those extra [requirements], because it does take time and the cost in some cases is huge. I think making researchers think about it earlier, but funders also being prepared to allocate resources to support that I think is key. [ID 25, senior trial manager]

Effective communication processes

Participants described the role of effective communication in successfully conducting trials involving adults lacking capacity. This included communication between members of trial teams when designing and co-ordinating trials, but also the importance of two-way communication between the trial team and those delivering the trial at research sites to ensure that key messages about the barriers being encountered and strategies to overcome them were being fed back. It also included communication between clinical staff and research staff at sites to more closely integrate research and clinical care and to ensure that potential participants and their consultees and legal representatives were being identified and communicated with.

We’ve got quite close links with the Trauma Coordinators, they’d be like I’ve already spoken to [the patient’s] next of kin, and she’s happy, here’s her number, and what have you. It’s about communicating as a whole team and to discuss it with colleagues and trial offices about the problems and things that were working well and things that weren’t. [ID 18, research nurse]

Communicating with potential participants with cognitive impairment was viewed by research nurses and others involved in recruitment as requiring confidence and experience, as well as having accessible information to facilitate information provision. This included the use of summary information sheets as well as alternative formats which could be used to scaffold information about the trial and enable to person to express their informed views about participation where possible.

We did actually have an aphasia friendly information leaflet for those who didn’t have capacity [to consent] but had some capacity to understand the study. It was a large font, so it was fourteen point, one and a half times spacing, the layout was in boxes with images, so that was all broken down. [ID 19, trial manager]

Other strategies to overcome communication difficulties included approaching the person when family members were present who could support the person to understand the information and make a decision about participation where possible, or the involvement of interpreters where language was considered to be a barrier. Where research nurses considered a communication disorder to play a role in capacity and decision-making, particularly for people who had experienced a stroke, some reported seeking the involvement of a speech and language therapist (SLT) or tagging their discussion about the trial onto the end of a routine SLT session where possible.

Effective communication was also viewed as an important part of engaging with family members who were approached to act as a consultee or legal representative and was considered to be particularly challenging when the approach was made remotely, e.g. via post, or when usual care teams had to be relied upon to send out information about the trial due to data protection requirements.

You don’t want to harass the relative. So, unless the relative contacts us, we can’t contact them. So, unless the relative says, I would like some more information about this, we can’t give them more information even though we’ve written to them. I naively said, ‘Well why can’t we ring them up a few days later, and check they’ve got the letter and ask them what they thought about it?’, but you can’t do that. [ID 11, Chief Investigator]

The challenges of family members making a decision about participation on the person’s behalf was also seen as a barrier, primarily around how families can be orientated to base their decision on the person’s wishes and feelings rather than their own views, and how they might access those wishes in the absence of explicit discussions about research participation.

I think it’s hard to try and say what that person would want if you haven’t specifically had that conversation with them previously about whether they’d want to be involved in research or even what types of research. It’s difficult when you’re asking someone to consent on behalf of someone else, they are always going to have their own views, and it’s difficult with the best will in the world, to make a decision based purely on what someone else would want and not what you would want. [ID 01, research governance lead]

Building a rapport with family members and using a person-centred approach to discuss what mattered most to the person was viewed as a useful approach to supporting the family member to make a decision based on the person’s wishes and feelings.

Issues around communication were also raised when there were changes in a person’s capacity status during a trial and consent was revisited. This including the use of a ‘deferred consent’ model where the person was enrolled without prior consent (or through brief verbal consent) during an emergency and then consent to remain in the trial was sought from them once they had recovered or their family approached if not [44]. In these situations, they had received the intervention at the point they were approached, and so they were informed about their participation and were asked to provide consent for data collection to continue. Participants recognised the sensitive and potentially challenging nature of these discussions, and the need to tailor the timing and approach to the context and the person’s ongoing health needs. Research nurses highlighted the importance of maintaining a relationship with the person, their family and the care team throughout their time in a study, including regular bedside conversations when completing visits to the ward for data collection. This also provided opportunities for ongoing assessment for any changes in capacity. Participants reported rarely encountering anyone who declined to continue in a trial, with high levels of acceptability towards the consent approach used, although there were instances of people being discharged or transferred or dying before consent could be sought.

At the time we get to them all the work has been done, so it’s just asking consent to keep the data and I’m always surprised at how accepting people are. It’s very rare that we have somebody that is really unhappy about what has happened, once you sit down and explain to them. And many patients are really happy that they’ve been able to contribute to improve treatment for somebody like them in the future. [ID 16, research team lead]

Good communication with RECs was also seen as facilitative, and research teams described how building a relationship with particular RECs meant that there was a shared understanding about the ethical issues involved and how trials could best be designed to overcome these. However, this supportive communication with RECs was not experienced by all researchers, with some expressing frustration with the process and the inability to discuss these complex applications in detail or in advance of submitting an application.

One of the panels didn’t seem to get it at all, and it was like really difficult to try and explain. The other problem is that when panel’s running behind they might not allow enough time and so when [the researchers] got into the room, they’ve got like five minutes and so they didn’t get a chance to answer, be asked or answer any of the questions or explain anything, so it was all very rushed, and not having a chance to actually talk through the study and have a conversation about it. [ID 15, Chief Investigator]

What would have been useful, and I don’t know whether it is accessible, is contacting REC beforehand to kind of talk through that proposal because, obviously, if we had had that conversation and they’d gone, well, you need to make these changes. Well, that could have just pretty much saved us probably two and a half, three months. That’s a massive amount of time. [ID 22, senior trial manager]

Use of adaptive strategies including COVID-19-related adaptations

The importance of designing in flexibility in a trial, and adapting processes in response to challenges encountered, was seen as key to the successful delivery of trials with this population, including in response to the pandemic. Participants expressed how COVID-19 had presented particular challenges which highlighted the need for adaptive strategies in response to the high numbers of acutely and critically ill patients, the introduction of Urgent Public Health studies with a pause in almost all non-COVID trials, and universal infection control measures. Challenges also included the involvement of research-naïve and redeployed staff who required rapid general research and trial-specific training that was sufficiently comprehensive but minimally burdensome. However, the greatest impact was the stopping of all hospital visitors which included family members who would act as consultees and legal representatives. Participants reported a change in many trials towards enabling remote forms of consultation with families through email, phone calls and video calling which facilitated the recruitment of people who lacked capacity to consent. This included COVID-19 trials as well as amendments to non-COVID trials in other settings such as care homes and the community. COVID-19 was seen by some as a driver in enabling long-awaited advancements in trial conduct.

I think there was question about whether that [the use of professionals as nominated consultees] could happen, but since COVID that has now come in as being acceptable and they’ve had a substantial amendment on the trial to allow for professional consultee [sic] to be enough. [ID 13, research nurse]

Research nurses talked about the value of sustaining this flexible approach and embedding it in more trials in the future that recruit adults lacking capacity.

It would be better to have a few more [studies allowing] consent that we could do over the phone with relatives. Because it’s something that we’ve found to be quite helpful to have with some of the COVID trials and they’ve adapted some of the non-COVID trials as well. But many of our trials don’t have that at all. [ID 16, research team lead]

However, others reported that the challenges of communicating about the trial with these populations and those who care for them may not be easily addressed through these adaptions which limit personal interaction and the building of relationships.

In the original study, we were going into the [care] home. We were going to meet people face to face and now we’re trying to do that remotely via Zoom, so it’s sort of turned into a different animal. In a way that also brings subtle changes to the way you engage with people. Very, very different. [ID 11, Chief Investigator]

Research nurses described the challenges of communicating about a trial with patients with COVID-19 who often had impaired capacity due to hypoxia or other conditions. This was intensified by the requirement for research staff to use PPE (personal protective equipment) and reduce physical contact which limited non-verbal communication, and patients requiring respiratory support such as CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) hoods which made it difficult for them to hear above the noise and meant that patients who usually wore glasses may not have been able to read information about the trial. Even research nurses who were familiar with impaired and fluctuating capacity in a range of conditions described the more complex nature of assessing hypoxia-related capacity impairment. Other COVID-19-related challenges included the infection control risk from contaminated paper consent forms which necessitated alternative approaches such as photographing or quarantining completed forms, or the use of witnessed verbal consent or e-consent with people with capacity as well as consultees/legal representatives for those who lacked capacity. However, the use of digital tools such as email and video conferencing raised additional concerns about the exclusion of those without access to such technology.

Outside of secondary care, challenges included care homes closing to all non-essential visitors which included research staff, and ‘lockdown’ restrictions which prevented research visits in primary care. For trials that remained open, this necessitated a rapid change in contact methods with potential participants, their families, and sites such as care homes, which could also be affected by limited digital access and poor connectivity issues. It also presented new challenges such as having to undertake virtual assessments of capacity which were unfamiliar to researchers.

However, research nurses reported a positive impact from COVID-19 where the high-profile and urgent search for effective treatments for this novel disease meant that there was a greater awareness about research in the general public. This facilitated discussions about trial participation with both patients and their families when contacted. COVID-19 adaptations also removed geographical location as a barrier to participation in some instances and led to greater embracing of digital technologies for some groups. This was seen in a study involving people with learning disabilities which originally recruited through local advocacy groups but switched to online recruitment and data collection.