Abstract

The recent high-profile cases of hate crimes in the U.S., especially those targeting Asian Americans, have raised concerns about their risk of victimization. Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, intimations—and even accusations—that the novel coronavirus is an “Asian” or “Chinese” virus have been linked to anti-Asian American hate crime, potentially leaving members of this group not only fearful of being victimized but also at risk for victimization. According to the Stop AAPI Hate Center, nearly 1900 hate crimes against Asian Americans were reported by victims, and around 69% of cases were related to verbal harassment, including being called the “Chinese Coronavirus.” Yet, most of the evidence martialed on spikes in anti-Asian American hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic has been descriptive. Using data from four U.S. cities that have large Asian American populations (New York, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington D.C.), this study finds that hate crime against Asian Americans increased considerably in 2020 compared with that of 2019. Specifically, hate crime against Asian Americans temporarily surged after March 16, 2020, when the blaming labels including “Kung flu” or “Chinese Virus” were used publicly. However, the significant spike after March 16, 2020, in anti-Asian American hate crime was not sustained over the follow-up time period available for analysis.

Keywords: hate crime, COVID-19, crime prediction, ARIMA, anti-Asian American

Hate crime is a distinct form of violence and aggression targeting a certain group of individuals on the basis of their religion, race/ethnicity, or gender identity (Chakraborti & Garland, 2012; Hall, 2013; Perry, 2001). This emotional, hostility-oriented aggression likely heightens or hardens the common expression of hate while sustaining social hurdles between individuals having different identities (Chakraborti, 2018). Scholars have proposed multiple reasons to explain why hate crime occurs. Some argue that critical/trigger events of local, national, and global significance could increase or decrease the frequency, severity, and the demographic group targeted by hate crime (Awan & Zempi, 2017; Chakraborti & Garland, 2015). Traditionally, terrorist attacks or domestic economic downturns, such as recessions or depressions, are believed to contribute to increases in hate crime (Byers & Jones, 2007; Hanes & Machin, 2014). Although there are likely to be several theoretical reasons as to why this may be the case, one commonly used framework anticipates that people tend to build more prejudice towards a group of distinct individuals, for example, an “outgroup,” and express prejudice as aggression or discrimination when visual and symbolic differences that distinguish between outgroups and ingroups are considered as the cause of tragic events, resulting in the amplified ingroup and outgroup social psychology (Allport, 1979; Byers & Jones, 2007; Jacobs & Potter, 1998).

The recent high-profile cases of hate crimes in the U.S., especially those targeting Asian Americans, have raised concerns about their risk of victimization. For example, on March 14, 2020, several members of an Asian American family in Texas were stabbed by a man since he believed this Asian family was infecting people with coronavirus (Kim, 2020). More recently, a 65-year-old woman was beaten outside of a New York City apartment with anti-Asian American racial slurs such as “you do not belong here” said to her on March 29, 2021 (Treisman, 2021). The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was accompanied by intimations—and even accusations—that the novel coronavirus is an “Asian” or “Chinese” virus. These sentiments and the high-profile cases of hate crime against Asian Americans may have left members of this group fearful of victimization simply because of their race/ethnicity (Sun, 2021). In fact, a recent Pew Research Center survey found a majority of Asian Americans worried about being threatened or attacked due to their race or ethnicity, and just over one-third of those that worried about victimization have made changes to their daily routines due to that fear (Noe-Bustamante et al., 2022). Regarding the “amplified prejudice perspective,” the recent pandemic coupled with the view of Asian Americans as permanent outsiders in society could amplify the prejudicial and discriminative perceptions among the in-group population in the U.S., resulting in an increase in hate crime against Asian Americans (Gover et al., 2020; Tessler et al., 2020).

Yet, most of the evidence martialed on spikes in anti-Asian American hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic have been descriptive (e.g., Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, 2021; Hswen et al., 2021). This useful evidence articulates a rapid increase in hate crime against Asian Americans along with the spread of COVID-19, but it remains largely under-documented. Accordingly, this study examines whether the recent spike of hate crime was linked to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and stay-at-home orders by empirically examining the trend of hate crime in several U.S. cities, including some which have the largest Asian American populations.1

Background

Hate Crime

In recent decades, hate crime has received increasing attention from citizens, politicians, and criminologists as a newer type of discrimination and criminal behavior that may heighten a hurdle for unification and harmony in society. Due to its nature, hate crime is distinct from traditional violent or property crime. The definition of hate crime highlights the motivation of aggressive behavior against a certain group of people in the form of hate, prejudice, and hostility underlying the commission of a crime, rather than the action that is the central theme in the traditional definition of crime (see Chakraborti, 2018). The underlying bias-based motivation is likely driven by differentiating or marginalizing other religions, genders, ethnic identities, or vulnerabilities/disabilities which are the core components of hate crime (Chakraborti & Garland, 2012; Hall, 2013; Perry, 2001).

According to the legal definition, hate crime is defined as “crimes that manifest evidence of prejudice based on race, gender and gender identity, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or ethnicity” (Hate Crime Statistic Act (28 U.S.C. § 534)). The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) also defines hate crimes as a “criminal offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity” (Federal Bureau of Investigation, n.d.). The US Department of Justice (DOJ) categorizes actions into hate crime and other hate incidents (Department of Justice, n.d.). Hate incidents are acts of prejudice that are not codified as crimes and they do not accompany traditional forms of criminal behavior such as violence, threats, or property damage. Hate crime involves violent and property crime, including harassment, assault, murder, arson, or vandalism, driven by biased motivation regarding the victim’s race, color, religion, nationality, disability, gender, or sexual orientation. In sum, the DOJ explains that hate crime may include all the violent or non-violent activities targeting marginalized individuals in any form of verbal harassment, assault, or bullying due to differences in religion, gender, sexual identity, or ethnicity.

COVID-19 and Hate Crime Increases

In 2020, the outbreak of COVID-19 and the ensuing global pandemic has influenced the everyday life of countless numbers of people around the world. As of May 20, 2022, more than 525 million people have been infected by COVID-19, with more than 6 million deaths attributed to COVID-19 (Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, n.d.). In the United States alone, as of May 20, 2022, just over one million people have lost their lives due to COVID-19 (Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, n.d.) In addition, the pause to everyday life in response to COVID-19 has resulted in unplanned negative changes, including unemployment, the disruption of education, aggravated financial polarization, and the global financial crisis (Boman & Gallupe, 2020). As well, pervasive stay-at-home orders, mask regulations, and other social distancing guidelines have caused unprecedented changes to everyone’s daily routines (i.e., working home remotely or avoiding crowded public spaces), interpersonal contact (i.e., social distancing or virtual meeting), and social interactions (i.e., avoiding neighbors).

Changes in crime as a result of the pandemic and its associated public health response has not gone unstudied either. According to major news outlets at the beginning of the pandemic, crime was decreasing across the United States (Jackman, 2020; Jacoby et al., 2020; Waldrop, 2020), which subsequent scholarly research has tended to confirm. Several dozens of studies have explored crime trends during this pandemic period, with the most consistent set of findings indicating increases in violent crimes throughout the later part of 2020, especially homicide, aggravated assault, and domestic violence (see Rosenfeld et al., 2021; Piquero et al., 2021). A recent, comprehensive study using daily counts of crime in 27 cities from 23 different countries showed that stay-at-home policies were associated with a decline in urban crime, but there was variability in this general conclusion across crime types and cities (Nivette et al., 2021).

Recently, the publicization of hate crime against the Asian population has triggered a debate about another negative consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic regarding crime. According to the Anti-Asian Hate Crime Report (2021), hate crimes against the Asian population increased by 145% in the 16 largest cities in the U.S. in 2020 compared with that of 2019. Also, one poll about COVID-19 revealed that more than 30% of respondents had seen someone blaming the Asian population for the spread of the COVID-19 virus (Ipsos, 2020).

Aforementioned, it is hypothesized that significant events (i.e., terrorist attacks or great economic downturns) are likely to trigger hostile emotions among the public, and individuals express those negative feelings in the form of microaggressions, violence, or other types of crime (Byers & Jones, 2007; Muzzatti, 2005). People in major groups tend to perceive various types of threats to their own culture and system from the outgroup which in turn lead to feelings of anger or rage, resulting in more acts of aggression and hostility (Cottrell & Neuberg, 2005; Smith & Mackie, 2015). According to Othering Theory, a racially/socially dominant group tends to differentiate or even marginalize a non-dominant group by labeling this outgroup as “others” and viewing them as deviant from the dominant culture and system (Grove & Zwi, 2006; Sundstrom & Kim, 2014). Moreover, when this type of prejudice is merged with the symbolic image of an outgroup that is considered to contribute to recent tragic events, the hostile attitudes and expressions against the outgroup are likely amplified (Byers & Jones, 2007). For instance, after the 9/11 terrorist attack, hate crime against Arab Americans and those of the Islamic faith considerably increased (e.g., approximately 1600% increase in 2001 compared to 2000) since those individuals were described as belonging to the same group responsible for the terrorist attack (Hanes & Machin, 2014; Swahn et al., 2003).2 The existing social perception that visually differentiated the ingroup from the outgroup along with negative attribution played a key element in increased hate crime against Islamic individuals who were considered outgroup members (Byers & Jones, 2007).

Asian Americans have also been considered as threats to the dominant group (e.g., White race) in Western societies due to the rise in economic, cultural, and military power since the 1880s, with this threat labeled as the “yellow peril” (Chen, 2000; Hsu, 2015; Kimura, 2021). In accordance with rapidly growing Asian immigration rates, the fear among ingroup members of being invaded by Asian populations has remained and appeared in the form of legislation (e.g., Immigration Act of 1924) or general perceptions viewing Asians as forever foreigners (Kil, 2012; Kimura, 2021; Tuan, 1998). Indeed, Asian Americans have been consistently treated with a stereotype of the model minority in secured and peaceful eras while being othered or isolated in times of economic downfall, wars, or pandemics [such as COVID-19] (Gover et al., 2020).

The novel coronavirus was first reported in Wuhan, China, and news sources in late January 2020 referred to it as the “Wuhan Virus,” or “Chinese Virus.” For example, one such article stated “a second person in the U.S. who visited China has been diagnosed with the Wuhan virus, officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Friday” (Szabo, 2020, para. 5). In addition, government officials, including Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in the Trump administration, used those terms during the second week of March in public appearances rather than referring to the novel coronavirus as COVID-19 (Boyer, 2020; Rogers, 2020). Some argued that these terminologies might connote racist or xenophobic messages to the public as they can sound like the promotion of aggression towards Asian Americans or they may be suggestive of excluding them from society (Gover et al., 2020). Regarding the spread of biased terms and blaming attitudes, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) warned in its mid-March intelligence report that hate crime against the Asian population could increase due to the presumed association between COVID-19 and Asian Americans (Margolin, 2020). According to the Stop AAPI Hate Center, nearly 1900 hate crime against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic were reported by victims, and around 69% of cases were related to verbal harassment, including being called the “Chinese Coronavirus” (Jeung & Nham, 2020). Also, Lee and Waters (2021) analyzed qualitative answers from 410 Asian respondents to a survey during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that around 30% of Asian American respondents experienced at least one type of hate crime or form of discrimination, such as being treated as a suspicious person in public, hearing racist jokes, being verbally or physical threatened, or overhearing racist comments. Taken together, it is hypothesized that the recent COVID-19 pandemic and widely spread blame on Asian Americans for coronavirus may contribute to an increase in hate crime against Asian Americans due to the amplified prejudice spawned by the pandemic and othering that already existed towards this outgroup’s members.

Current Study

The present work focuses on the recent purported surge in hate crime, with a special focus on hate crime against Asian Americans in the U.S. The aim of the study is twofold. First, the trends of hate crime against Asian Americans are examined to assess whether they evinced any change(s) during the pandemic, especially with the use of the blaming label for Asian Americans such as “Chinese Virus” or “Kung flu.” Second, this study is designed to statistically analyze whether the trends of general hate crime show unprecedented changes. The examination of overall hate crime trends is expected to provide hints on whether overall hate crime increased during the COVID-19 pandemic or whether hate crime against Asian Americans is the only type of hate crime statistically associated with this unprecedented event. For this study, data were drawn from multiple police departments to analyze changes in anti-Asian American hate crime during the pandemic that move beyond the descriptive analyses that exist.

Method

Data

The data for this study is comprised of two sets of hate crime data drawn from multiple police departments of some of the largest metropolitan cities in the U.S. Specifically, weekly general hate crime information between 2019–2020 is drawn from four police departments (New York, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington D.C.), while weekly anti-Asian American hate crime data were collected from the same four cities from January 2019 to March 2021. It is, of course, ideal to include many cities or a representative sample to maximize the generalizability of the study findings, but not all cities count (and/or report) hate crime, disaggregate hate crime by race/ethnicity, or provide data in a format suitable for time-series analysis. As a result, we relied on a convenience sample consisting of four U.S. metropolitan cities with large Asian American populations. In total, we had 104 observations for the weekly hate crime dataset and 116 complete observations for the weekly dataset for hate crime against Asian Americans. Datasets were comprised of data gathered from public city data portals or provided based upon public information requests.3

Looking at the number of hate crime each year in Table 1, three out of four cities reported decreases in hate crime between 2019 and 2020. Only Seattle showed an increase in hate crime in 2020 relative to 2019, with hate crime increasing by 63% in 2020. Also, Seattle received the largest volume of calls regarding hate crime, while San Francisco, in general, had the fewest reports of hate crime during the study years. With respect to hate crime against Asian Americans, considerable increases were observed in New York, Seattle, and San Francisco. New York appeared to have the greatest increase in hate crime against Asian Americans, with an increase of 3200%, from 1 incident in 2019 to 33 in 2020. In Seattle, overall hate crime and those against Asian Americans increased, even doubling among Asian Americans. It is important to note that hate crime against Asian Americans is a relatively rare event, and as such, small denominators and numerators can greatly influence percent change calculations. Because of this, we employ multiple methodological techniques to assess the state of hate crime in our four-city sample, to which we now turn.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Hate Crime in Four Cities Between 2019–2020.

| City | % of Population- AAPI | Hate Crime | Anti-Asian American Hate Crime | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | Change | 2019 | 2020 | Change | ||

| New York | 14.4 | 447 | 284 | −36% | 1 | 33 | 3200% |

| San Francisco | 34.9 | 83 | 57 | −31% | 8 | 9 | 12% |

| Seattle | 16.6 | 484 | 791 | 63% | 24 | 55 | 129% |

| Washington D.C. | 4.1 | 203 | 132 | −35% | 6 | 1 | −83% |

Note. Percent of AAPI population is drawn from 2019 American Community Survey.

Measurement

The definition and guidelines for hate crime are heterogeneous across the nation. Each police department defines hate crime following their city and state code or regulation. For instance, Seattle has a more expansive definition because police have three categorizations: bias incidents, crimes with bias elements, and hate crimes.4 Similarly, the New York and San Francisco Police Departments include both hate crime and bias incidents as unlawful acts that need to be reported to police. Meanwhile, the Washington, DC Metropolitan Police Department articulates that hate crime must be a criminal act based on the offender’s prejudice or bias.

The US Attorney General’s Office released a memo on May 27, 2021, relaying information from the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act and Jabara-Heyer NO HATE Act and explaining the DOJ’s goal to combat both hate crimes and hate incidents (Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General, 2021). While hate crimes and hate incidents may be distinct, the memo stressed how both may lead to fear within minority communities. Following the Attorney General’s May 2021 memo, and due to the limitation in differentiating hate crime from hate incidents in the data available from police departments, we operationalized hate crime as hate crimes and hate incidents reported to police departments. In particular, we analyze a weekly series of hate crime that includes all types of criminal behavior targeting any demographic groups as well as a weekly series of hate crime against Asian Americans. Data were aggregated to weekly counts, with the first week starting on January 7, 2019 (Monday) and running through January 13, 2019 (Sunday).

Due to this coding scheme, week 63 of our data (week 12 of 2020) starts with March 16, 2020, the third week of March 2020, and we considered week 63 as the start of the “intervention” for our analyses, or the break point marking the beginning of anti-Asian American rhetoric and stay-at-home orders related to the spread of COVID-19. We use the term “intervention” here and throughout the text to refer to the break point marking the beginning of anti-Asian American rhetoric related to the spread of COVID-19, something we believe to act as an exogenous force that might interrupt the pre-existing trend in anti-Asian American hate crime. In particular, we selected March 16, 2020, as the break point and segmented weekly data into pre- (January 7, 2019 to March 15, 2020) and post-intervention (March 16, 2020 to March 28, 2021). While there may have been public anti-Asian American remarks made in reference to COVID-19 prior to this date, Hswen et al. (2021) have documented the first expansive spread of this sentiment occurred March 16, 2020. Furthermore, in the third week of March 2020, most cities, counties, and states in the U.S. had issued mandatory stay-at-home orders in order to curb the spread of COVID-19. Previous studies also set March as a break point to examine the increase/decrease in crime during the pandemic (e.g., March 24th in Piquero et al., 2020).5 Additionally, some officials in the Trump administration started using terms like “Chinese virus,” “China virus,” or “Kung flu” after Trump made those remarks himself in mid-March (Gover et al., 2020; Hswen et al., 2021; Rogers, 2020; Scott, 2020).6

Analytic Plan

To explore the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, stay-at-home orders, and accompanying rhetoric that may have inflamed hostile attitudes and behavior towards Asian Americans in the middle of March 2020, we employ two separate analytical techniques: an ARIMA forecasting approach and a trend analysis. First, the ARIMA forecasting approach uses data from before the intervention to train an ARIMA model to predict hate crime after the intervention and then compares observed values to prediction intervals to assess whether crime significantly increased or decreased relative to what we might have expected. Point estimates and 80 and 95% prediction intervals centered on the point estimates were generated for this study for eight periods (8 weeks) post-intervention for the weekly series. If an observed (actual) value falls above a predicted interval’s upper limit, this means the data point is significantly different from what we might have expected to happen 80 or 95% of the time.

Our second approach for examining the trends of hate crime against Asian Americans is interrupted time-series analysis (ITSA), also known as trend analysis. ITSA is typically used to evaluate the impacts of an intervention by comparing outcomes of the pre- and post-intervention periods. The intervention refers to the treatment, and the pre-intervention period is utilized to compare the outcomes of an intervention. In this study, the 16th of March 2020 where the COVID-19 pandemic became widely spread so much that it began leading to stay-at-home orders and the blaming of Asian Americans for COVID-19 appeared in media reports is considered our “intervention” point, or the beginning of the “treatment” (i.e., anti-Asian American rhetoric). The data utilized is weekly anti-Asian American hate crime between January 7, 2019, and March 28, 2021, resulting in 116 weeks of observation. Therefore, anti-Asian American hate crime from the period of the 1st week of January 2019 through the 2nd week of March 2020 constitutes the pre-intervention series while data from the 3rd week of March 2020 through 2021 comprises the post-intervention series. The statistical package “itsa” in STATA is used (Imbens & Lemieux, 2008), and the model is presented in the form of the following equation:

where denotes the hate crime against Asian Americans, Tt represents the time since the start of the study, is a dichotomous variable indicating the intervention, and is an interaction term (Linden, 2015). Therefore, represents temporal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic while represents continuous effects over time.

We begin by investigating weekly counts of hate crime against Asian Americans in our four-city sample with an ARIMA forecasting approach. Dickey-Fuller tests for the presence of a unit root and the “auto.arima” function in R were used to identify the best model for our data based on the 62 observations from the 1st week of January 2019 through the 2nd week of March 2020 to project eight weeks post-intervention. Second, we use the trend analysis approach with a longer follow-up period to examine anti-Asian American hate crime in our four-city sample. This analysis allows researchers to examine whether the increase/decrease in hate crime against Asian Americans is a temporary or a longer-lasting change, at least within the window of the data available. Lastly, the weekly counts of overall hate crime were analyzed with a secondary analysis of four cities, projecting eight weeks post-intervention.7

Results

Anti-Asian American Hate Crime

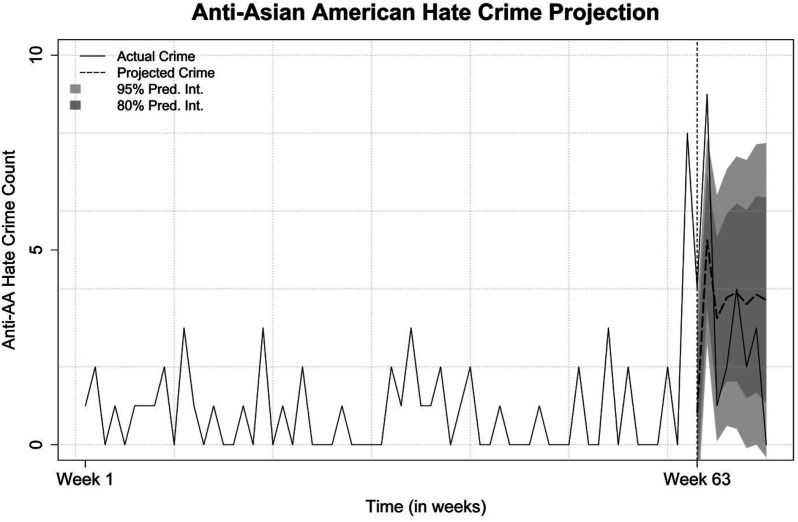

With our forecasting approach, we used the “auto.arima” function in R to fit a model to a subset of our data (weeks 1 through 62) to then test the observed data against 80 and 95% prediction intervals. According to the “auto.arima” results, the best fitting model is an ARIMA model of order (2,0,0) based on the first 62 weeks of data to predict the 8 weeks after March 16, 2020. However, the results of a Dickey-Fuller test suggested there is a unit-root and the series is non-stationary. A subsequent Dickey-Fuller test of the first difference of the data suggests the first difference of the series is stationary. To account for this, we fit an ARIMA model of order (2,1,0) to our data. The results displayed in Figure 1 show anti-Asian American hate crime spiked above the upper bound of the 95% prediction interval in the first week after the intervention and then returned to expected levels in the weeks thereafter.

Figure 1.

Weekly Anti-Asian American Hate Crime Projection, 4 Cities.

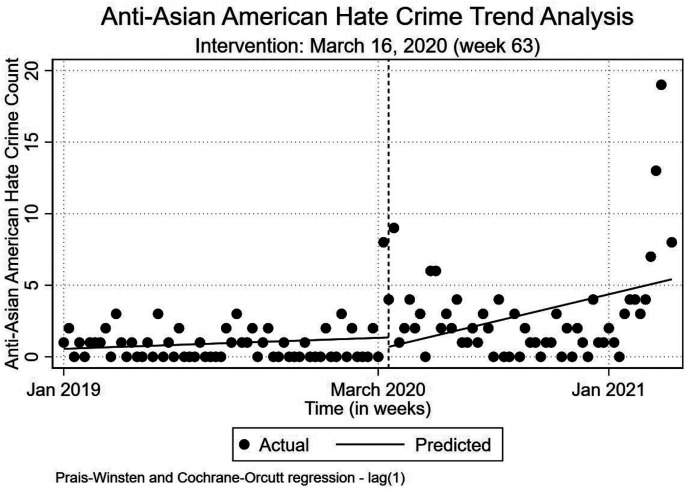

To conduct a longer-term evaluation of the trend of anti-Asian American hate crime, we employed 116 full weeks of observed data to conduct our trend analysis, with week 1 beginning Monday January 7, 2019, and the final week ending Sunday March 28, 2021. The intervention begins in week 63 of our data, or the 12th week of 2020. Table 2 contains the results for the trend analysis, and Figure 2 visually displays the estimated trend lines before and after our intervention. Using the “itsa” command in STATA to estimate pre- and post-trend linear regression estimates, although we see visual evidence of an initial spike in anti-Asian American hate crime, we found no statistically significant change to the trend of anti-Asian American hate crime in our four study cities.

Table 2.

Trend Analysis, Anti-Asian American Hate Crime Results (N = 116).

| Variables | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | SE | t | |

| Time before March 16, 2020 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.56 |

| Start of March 16, 2020 | −0.651 | 1.45 | −0.45 |

| Time after March 16, 2020 | 0.075 | 0.056 | 1.32 |

| Constant | 0.559 | 0.583 | 0.96 |

| F (3, 112) | 3.86* | ||

Note. * = p < .05.

Figure 2.

Anti-Asian American Hate Crime Trend Analysis.

The results in Table 2 can be interpreted as follows. The coefficient for the time before March 16, 2020, is the slope estimate for weeks 1 through 62 of our data. The start of March 16, 2020 is the estimated increase associated with the start of our intervention (week 63) and the time after March 16, 2020 coefficient is the estimated change in the slope from pre-to post-intervention. The post-intervention slope estimate can be calculated by adding together the coefficients for the time before March 16, 2020 (b = 0.013) and the time after March 16, 2020 (b = 0.075) to have an estimated post-intervention slope estimate of 0.088.8 However, none of the parameter estimates are statistically significant, which means there was no identifiable trend (increasing or decreasing) before the intervention, and there was no statistically significant increase or decrease in the slope associated with the intervention.

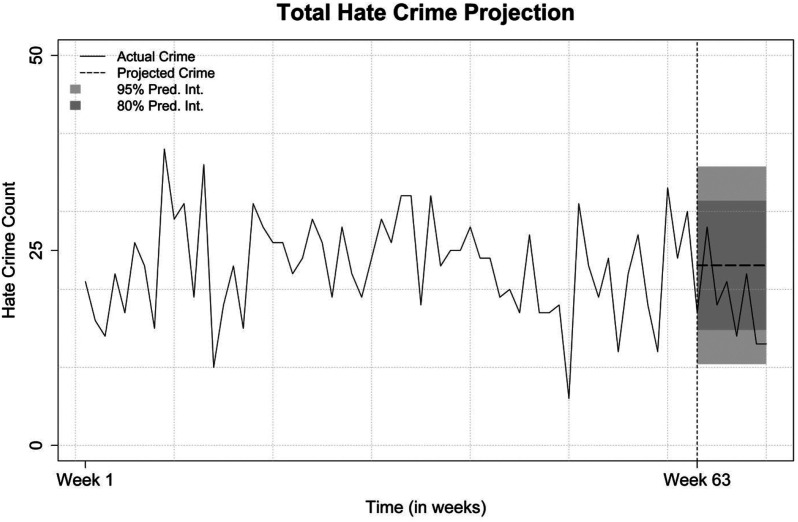

Total Hate Crime Forecasts

After considering model fit and the presence of a unit root, a final ARIMA model order of (0,0,0) was specified for the weekly hate crime series. Data were stationary, and there was no need to difference the series. Figure 3 displays the weekly hate crime forecast for our four-city sample. As can be seen in Figure 3, actual hate crime statistics for the weeks after the intervention did not exceed what we might expect them to be based on prior values. There was not an observable spike in total hate crime like there was for anti-Asian American hate crime. This might suggest the increase in anti-Asian American hate crime was due to a factor that might influence it alone and not affect all hate crime in our sample. This is particularly important because we detected a sudden (though short-term) spike for hate crime on Asian Americans that was not observed for more general hate crime, that happened to coincide with not just stay-at-home orders, but more importantly (and we believe not coincidentally) anti-Asian American remarks made by many influential persons that may have influenced members of the public.

Figure 3.

Weekly Hate Crime Projection, 4 Cities.

Discussion

Various media outlets have reported increases in hate crime against Asian Americans amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a concern over the risk of victimization within the Asian American community. In fact, on March 20, 2021, President Biden signed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act, due in large part to attacks on the Asian American community, signifying that the issue was a priority among the highest levels of the U.S. government (Cathey, 2021). Our investigation comes on the heels of the descriptive research that has highlighted increases in anti-Asian American hate crime by applying two statistical modeling approaches to gauge whether there have been significant increases since the early stages of the pandemic and especially when high profile individuals started to use derogatory terms to describe the virus in public.

Two notable findings emerge from our multi-city research. First, descriptive statistics show that hate crime against Asian Americans increased considerably in 2020 compared with that of 2019. Three out of four cities in the study sample experienced a dramatic increase in hate crime against Asian Americans while overall hate crime incidents decreased during the study period for three of our four cities between 2019 and 2020. Further empirical analysis also revealed that hate crimes against Asian Americans temporarily surged after March 16, 2020, when the blaming labels including “Kung flu” or “Chinese Virus” were stated in the media by certain political officials.9 Indeed, Asian Americans have long been considered as “foreigners,” and their communities have continued to experience being excluded and ”othered” by the culture of racism and xenophobia (Grove & Zwi, 2006; Kim & Sundstrom, 2014). Also, the repetitive emergence of anti-Asian American stereotypes caused by yellow peril occurred with the myths inherently differentiating Asian Americans from the majority population (Gover et al., 2020; McGowan & Lindgren, 2006). When prejudice towards the outgroup was coupled with accusations of spreading the coronavirus, ingroup and outgroup differences were amplified, likely leading to the short-term spike in anti-Asian American hate crime. Adding to the prevalent and chronic discriminatory culture, the blaming labels on Asian Americans for stay-at-home orders and subsequent financial restrictions and tremendous loss of life in the COVID-19 pandemic is deemed as spiking the surge of hate crime against Asian Americans.10 Although we grant that this remains speculative, we are stricken by the spikes observed and encourage subsequent efforts to gather the necessary data to better examine individual-level motivation to fully assess the theoretical notions posited above.

This finding notwithstanding, it is also important to note that the significant spike in anti-Asian American hate crime was not sustained over time—at least with the follow-up data available for our analysis. There are possible reasons explaining this eventual stabilization, if it indeed has stabilized. As Chakarborti (2018) argued, three elements may play important roles in reducing hate crime and eliminating the discriminatory culture against a specific group of individuals in society: dismantling barriers to reporting, prioritizing meaningful engagement with diverse communities, and delivering meaningful criminal justice interventions. In this regard, police actively responded to hate crime, especially against Asian Americans. For instance, NYPD deployed plainclothes officers to Asian-populated areas in order to prevent hate crime. This initiative operated with a strong message that when people discriminate or target a person of a different identity, whether it is verbal, menacing activity, or anything else, the victim could be a plainclothes New York City police officer (Eyewitness News, 2021). In addition, there were police departments that launched new taskforces/teams to deal with hate crime or opened their website for reporting hate crime victimization along with recently opened social organizations helping to report hate crime victimization (e.g., Stop AAPI Hate). These massive efforts to combat hate crime against Asian Americans might have delivered a strong message to the public that hate crime is no longer acceptable while encouraging involvement of communities in helping address social issues together.

In spite of the findings emanating from our multi-city investigation, we are also mindful of the limitations of our work. First, our data were limited to four large U.S. cities, therefore additional work in other U.S. cities (as well as cities around the world) would be important. Second, due to the lack of a uniform definition, the definition of hate crime is not perfectly consistent across the four cities in the current study. For instance, Seattle holds a wider definition of hate crime compared with that of Washington D.C. Since the data could not be reliably disaggregated into hate crimes and hate incidents, separating the two might yield alternative findings. Thus, future studies need to examine the differential effects of policies on hate crime and hate incidents, as well as the effects each have on perceptions of safety within targeted communities. Third, this study relies on official records and has not captured hate crime that were not reported to the police. Since hate crime may not always be person- or violence-oriented, there is a need to try and capture as many of these non-traditional hate crimes as possible. Lastly, it would be important as well to interview offenders who committed these acts in order to better understand and ascertain their motivations and whether their actions were influenced by the statements made of any particular individuals. This will be important to assess not only the theoretical rationales highlighted earlier in the work but other frameworks and constructs that may also yield insight.

Hate crime has a long history, and significant events likely trigger the blaming labels on a certain group of people in society due to different identities. In order to address its adverse effects, the community of scholars and government officials should continue to track the effects of COVID-19 and provide adequate service to people in need.

Author Biographies

Sungil Han, PhD is an Assistant Professor in the Criminal Justice and Criminology Department at the University of North Carolina Charlotte. His research interest includes environmental criminology, immigration and crime, and issues related to communities and crime

Jordan R. Riddell, PhD is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Missouri State University. His research interests include the spatial-temporal analysis of crime and criminal justice education

Alex R. Piquero, PhD is a professor and chair of the Department of Sociology and Criminology, Arts and Sciences Distinguished Scholar at The University of Miami and professor of Criminology at Monash University in Melbourne Australia. He is also editor of Justice Evaluation Journal. His research interests include criminal careers, criminological theory, crime policy, evidence-based crime prevention, and quantitative research methods. He has received several research, teaching, and service awards and is fellow of both the American Society of Criminology and the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences. He has received several research, teaching, and mentoring awards and in 2019, he received the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences Bruce Smith, Sr. Award for outstanding contributions to criminal justice. In 2020, he received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Division of Developmental and Life Course Criminology.

Notes

Due to the limitation in differentiating hate crime from hate incidents in the data available from police departments, we operationalized hate crime as hate crimes and hate incidents reported to police departments.

According to the FBI statistics, 28 anti-Islamic hate crime occurred in 2000 compared to 481 hate crime against the Islamic population in 2001. https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ucr/hate-crime/services/cjis/ucr/publications#Hate-CrimeStatistics

Datasets are available at links below: New York: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/stats/reports-analysis/hate-crimes.page. Seattle: https://www.seattle.gov/police/information-and-data/bias-crime-unit/bias-crime-dashboard. Washington D.C.: https://mpdc.dc.gov/hatecrimes

The term “Bias Crime” is interchangeably used with “Hate Crime”. Since hate crime is motivated by bias it is widely called bias crime as well.

Most cities in the US implemented stay-at-home orders between the middle to the end of March.

According to Vox (and other outlets), then US President Trump first started making anti-Asian American COVID-related remarks around March 16 (https://www.vox.com/2020/3/18/21185478/coronavirus-usa-trump-chinese-virus).

To be sure, it is challenging to determine whether the dramatic spike after March 16, 2020, stems solely from the blame targeted at Asian Americans for spreading COVID-19 or from the possible effects of stay-at-home orders (or even some combination thereof). The key here will be if the intervention had a significant effect on hate crime against Asian Americans more than regular hate crime, it may be assumed that the labeling might have influenced the spike of hate crime against Asian Americans.

According to the post-intervention trend results, the post-trend slope estimate is also not statistically significant.

According to Figure 1, the unique spike in hate crime against Asian Americans is observed just before the 16th of March 2020 which is the intervention point of the study. A set of interrupted time series analyses with a new break point which is the first week of March 2020 were conducted and the results showed similar findings indicating a short and significant spike after the first week of March 2020 but insignificant increasing trends after the intervention period.

Given that stay-at-home orders were implemented around the fourth week of March in three sample cities (New York: March 22, San Francisco: March 17, Seattle: March 23, Washington D.C.: March 30) the spike in the third week of March can be linked (but causality remains uncertain) to the blaming labels.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Sungil Han https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5438-9520

References

- Allport G. W. (1979). The nature of prejudice (25th Anniversary Edition). Addison-Wesely. [Google Scholar]

- Awan I., Zempi I. (2017). ‘I will blow your face OFF’—VIRTUAL and physical world anti- muslim hate crime. The British Journal of Criminology, 57(2), 362–380. [Google Scholar]

- Boman J. H., Gallupe O. (2020). Has COVID-19 changed crime? Crime rates in the United States during the pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 537–545. 10.1007/s12103-020-09551-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer D. (2020). Trump spars with reporter over accusation that staffer called coronavirus 'Kung flu’. The Washington Times. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2020/mar/18/trump-spars-reporter-over-accusation-staffer-calle/ [Google Scholar]

- Byers B. D., Jones J. A. (2007). The impact of the terrorist attacks of 9/11 on anti-Islamic hate crime. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 5(1), 43–56. 10.1300/j222v05n01_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cathey L. (2021). Biden signs anti-Asian hate crime bill marking 'significant break’ in partisanship. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/biden-sign-anti-asian-hate-crime-billlaw/story?id=77801857 [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism . (2021). Report to the nation: Anti-Asian prejudice and hate crime. https://www.csusb.edu/hate-and-extremism-center [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti N. (2018). Responding to hate crime: Escalating problems, continued failings. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(4), 387–404. 10.1177/1748895817736096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti N., Garland J. (2012). Reconceptualizing hate crime victimization through the lens of vulnerability and ‘difference. Theoretical Criminology, 16(4), 499–514. 10.1177/1362480612439432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti N., Garland J. (Eds.), (2015). Responding to hate crime: The case for connecting policy and research. Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. Y. L. (2000). Hate violence as border patrol: An Asian American theory of hate violence. Asian LJ, 7(1), 69. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell C. A., Neuberg S. L. (2005). Different emotional reactions to different groups: A sociofunctional threat-based approach to“ prejudice”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(5), 770–789. 10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Justice . (n.d.). Learn about hate crimes. https://www.justice.gov/hatecrimes/learn-about-hate-crimes/chart [Google Scholar]

- Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General . (2021). Memorandum for department of justice employees: Improving the department’s efforts to combat hate crimes and hate incidents. https://www.justice.gov/ag/page/file/1399221/download [Google Scholar]

- Eyewitness News . (2021). NYPD announces new initiative to combat anti-Asian hate crimes in NYC. ABC7 New York. https://abc7ny.com/anti-asian-hate-crimes-nypd-initiative-bias-crime/10447140/ [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation . (n.d.). Hate Crimes. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/civil-rights/hate-crimes [Google Scholar]

- Gover A. R., Harper S. B., Langton L. (2020). Anti-Asian hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the reproduction of inequality. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 647–667. 10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove N. J., Zwi A. B. (2006). Our health and theirs: Forced migration, othering, and public health. Social Science & Medicine, 62(8), 1931–1942. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall N. (2013). Hate crime. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hanes E., Machin S. (2014). Hate crime in the wake of terror attacks: Evidence from 7/7 and 9/11. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 30(3), 247–267. 10.1177/1043986214536665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu M. (2015). The good immigrants: How the yellow peril became the model minority. Princeton University Press. 10.1515/9781400866373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hswen Y., Xu X., Hing A., Hawkins J. B., Brownstein J. S., Gee G. C. (2021). Association of “# covid19” versus “# chinesevirus” with anti-Asian sentiments on Twitter: March 9–23, 2020. American Journal of Public Health, 111(5), 956–964. 10.2105/ajph.2021.306154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbens G. W., Lemieux T. (2008). Regression discontinuity designs: A guide to practice. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2), 615–635. 10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos . (2020). New center for public integrity/Ipsos poll finds most Americans say the Coronavirus pandemic is a natural disaster. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/center-for-public-integrity-poll-2020 [Google Scholar]

- Jackman T. (2020). Amid pandemic, crime dropped in many U.S. cities, but not all. https://www.washingtonpost.com/crime-law/2020/05/19/amid-pandemic-crime-dropped-many-us-cities-not-all/ [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J. B., Potter K. (1998). Hate crimes: Criminal law and identity politics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby K., Stucka M., Phillips K. (2020). Crime rates plummet amid the coronavirus pandemic, but not everyone is safer in their home. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2020/04/04/coronavirus-crime-rates-drop-and-domestic-violence-spikes/2939120001/ [Google Scholar]

- Jeung R., Nham K. (2020). Incidents of coronavirus-related discrimination. http://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/wpcontent/uploads/STOP_AAPI_HATE_MONTHLY_REPORT_4_23_20.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center . (n.d.). COVID-19 dashboard. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Google Scholar]

- Kil S. H. (2012). Fearing yellow, imagining white: Media analysis of the Chinese exclusion act of 1882. Social Identities, 18(6), 663–677. 10.1080/13504630.2012.708995 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. (2020). Report: Sam’s Club stabbing suspect thought family was ‘Chinese infecting people with coronavirus’. https://www.kxan.com/news/crime/report-sams-club-stabbing-suspect-thought-family-was-chinese-infecting-people-with-coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K. (2021). “Yellow Perils,” revived: Exploring racialized Asian/American affect and materiality through hate discourse over the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Hate Studies, 17(1), 133–145. 10.33972/jhs.194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Waters S. F. (2021). Asians and Asian Americans’ experiences of racial discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on health outcomes and the buffering role of social support. Stigma and Health, 6(1), 70–78. 10.1037/sah0000275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linden A. (2015). Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. The Stata Journal, 15(2), 480–500. 10.1177/1536867x1501500208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin J. (2020). FBI warns of potential surge in hate crimes against Asian Americans amid coronavirus. https://abcnews.go.com/US/fbiwarns-potential-surge-hate-crimes-asianamericans/story?id=69831920 [Google Scholar]

- McGowan M. O., Lindgren J. (2006). Testing the model minority myth. Nw. UL Rev, 100(1), 331. [Google Scholar]

- Muzzatti S. L. (2005). Bits of falling sky and global pandemics: Moral panic and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Illness, Crisis & Loss, 13(2), 117–128. 10.1177/105413730501300203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nivette A. E., Zahnow R., Aguilar R., Ahven A., Amram S., Ariel B., Burbano M. J. A., Astolfi R., Baier D., Bark H. M., Beijers J. E. H., Bergman M., Breetzke G., Concha-Eastman I. A., Curtis-Ham S., Davenport R., Diaz C., Fleitas D., Gerell M., Eisner M. P. (2021). A global analysis of the impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions on crime. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(7), 868–877. 10.1038/s41562-021-01139-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe-Bustamante L., Ruiz N.G., Lopez M.H., Edwards K. (2022). About a third of Asian Americans say they have changed their daily routine due to concerns over threats, attacks. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/05/09/about-a-third-of-asian-americans-say-they-have-changed-their-daily-routine-due-to-concerns-over-threats-attacks/ [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. (2001). In the name of hate: Understanding hate crimes. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A. R., Jennings W. G., Jemison E., Kaukinen C., Knaul F. M. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic-Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 74, 101806. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A. R., Riddell J. R., Bishopp S. A., Narvey C., Reid J. A., Piquero N. L. (2020). Staying home, staying safe? A short-term analysis of COVID-19 on Dallas domestic violence. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 601–635. 10.1007/s12103-020-09531-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K. (2020). Politicians’ use of ‘Wuhan virus’ starts a debate health experts wanted to avoid. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/10/us/politics/wuhan-virus.html [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld R., Abt T., Lopez E. (2021). Pandemic, social unrest, and crime in U.S. Cities: 2020 Year-end Update. Council on Criminal Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. (2020). Trump’s new fixation on using a racist name for the coronavirus is dangerous. VOX. https://www.vox.com/2020/3/18/21185478/coronavirus-usa-trump-chinese-virus [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. R., Mackie D. M. (2015). Dynamics of group-based emotions: Insights from intergroup emotions theory. Emotion Review, 7(4), 349–354. 10.1177/1754073915590614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W. (2021). The pain and fear of anti-Asian hate crimes hits close to home. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/11/op-ed-the-pain-and-fear-of-anti-asian-hate-crimes-hits-close-to-home.html [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom R. R., Kim D. H. (2014). Xenophobia and racism. Critical Philosophy of Race, 2(1), 20–45. 10.5325/critphilrace.2.1.0020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn M. H., Mahendra R. R., Paulozzi L. J., Winston R. L., Shelley G. A., Taliano J., Saul J. R. (2003). Violent attacks on Middle Easterners in the United States during the month following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Injury Prevention, 9(2), 187–189. 10.1136/ip.9.2.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo L. (2020). Something far deadlier than the Wuhan virus lurks near you. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/flu-far-deadlier-than-wuhan-virus/ [Google Scholar]

- Tessler H., Choi M., Kao G. (2020). The anxiety of being Asian American: Hate crimes and negative biases during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 636–646. 10.1007/s12103-020-09541-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman R. (2021). Attack on Asian woman in Manhattan, as bystanders watched, to be probed as hate crime. https://www.npr.org/2021/03/30/982745950/attack-on-asian-woman-in-manhattan-as-bystanders-watched-to-be-probed-as-hate-cr

- Tuan M. (1998). Forever foreigners or honorary whites?: The Asian ethnic experience today. Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop T. (2020). Coronavirus has police everywhere scrambling to respond as their forces are reduced. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/01/us/police-coronavirus/index.html [Google Scholar]