Abstract

The arrival of a newborn is often a happy event in a woman’s life. However, many women experience perinatal distress such as anxiety disorders and depression during pregnancy or postpartum period. Although the positive interpersonal relationships of women with their wider environment seem to be a support network, research shows that support provided by partners is a very important protective factor in reducing mental health disorders in both prenatal and postnatal period in a woman's life. for this reason, more research needs to be done in the field of perinatal distress in order to clarify the causes that lead to mental disorders and to strengthen the partner’s role in the management of perinatal mental disorders of women.

Keywords:perinatal mental health, perinatal distress, perinatal mental disorders, perinatal anxiety, perinatal depression, perinatal PTSD, perinatal OCD, postpartum psychosis, support from spouse.

BACKGROUND

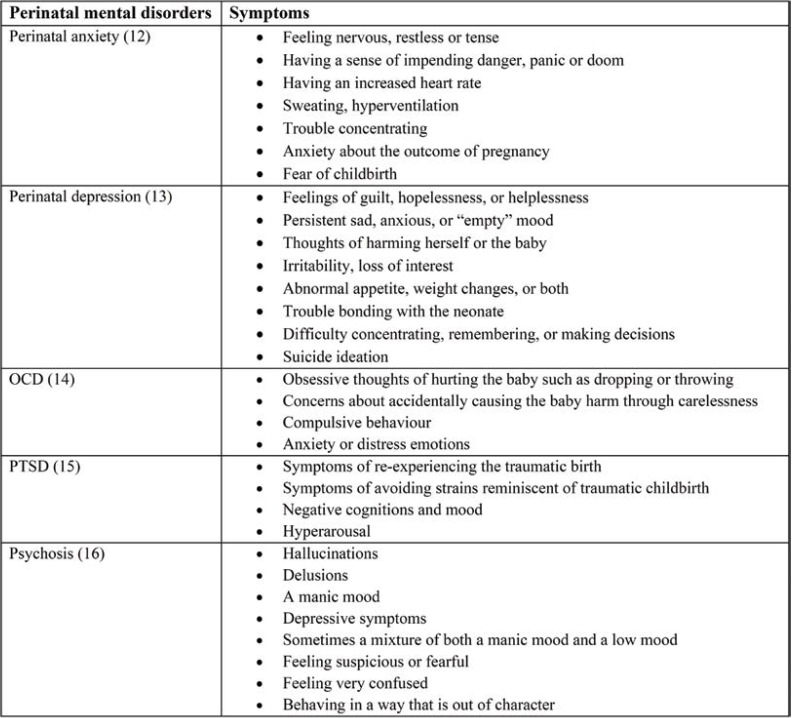

Preventing perinatal mental health problems is crucial due to the unpropitious effects on women and their family. Support from the partner is considered to be the ideal way, as it is a factor in preventing and treating the mother's mental disorders (1). Perinatal mental disorders include anxiety, depression (2), posttraumatic stress disorder (3), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (4) and psychosis (5) (Table 1).

The prenatal period is defined as the period from the start of the pregnancy to the onset of labour, while the postnatal period includes the period of six weeks after delivery (6, 7). The perinatal period is defined as pregnancy and the first year postpartum and it represents a time in women's lives that involves significant physiological and psychosocial change and adjustment (8). The perinatal mental health period, encompasses the mental health problems which occur either during pregnancy or in the first year following the birth of a child (9).

Data related to perinatal mental disorders showed a high prevalence during the postpartum period, while 19.8% of women have postnatal mental health disorders compared to 15.6% of women who have the same disorders prenatally (10), indicating that the postpartum period is slightly more sensitive to the development of mental disorders. Since the perinatal period is a very sensitive period for the development of perinatal disorders, social support, and especially support from the partner, is critical in the adverse effects of the perinatal illness (11).

So, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the support from the partner and its impact on maternal perinatal mental disorders. In order to achieve this goal, an international literature searching in Google Scholar, PubMed, Crossref and PsycINFO was carried out. We selected all studies that included the following variables: partner support or partner lack of support and perinatal outcomes on women mental health. Languages other than English as well as articles published before 2009 were excluded from the present literature review.

The feeling of fear is quite usual during pregnancy, with an estimated percentage of 80% of pregnant women showing signs of stress with regard to labor pain but also to the safety and health risks of the process (1, 14). These types of fear do stand to reason and the majority of women are able to express and control these feelings by being well-informed about the birth process, discussing their worries with other women who have already experienced childbirth and seeking advice from a midwife or doctor (1). In some cases, however, fear results in tocophobia and it is estimated that 3% of women develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after childbirth (1). This rate increases in women at high risk of developing psychological problems and postpartum PTSD symptoms may include the revival of childbirth and nightmares of the event (1, 15).

Anxiety and depression are attributed to some extent to the hormonal changes of this period – they are the most commonly observed symptoms in the perinatal period and often extend from the beginning of pregnancy up to two years later in some cases (17). In addition, perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms may have negative effects on infant and child health as they are associated with premature birth, perinatal complications and cesarean sections (18). More specifically, the prevalence of perinatal anxiety during pregnancy varies between 8.5% and 10.5% and it is higher than in general population (between 1.2% and 10.5%). The disorder appears to evident in women who have a family history of anxiety or other mood disorders (19). Perinatal anxiety can appear with different conditions such as generalized anxiety. Pregnancy related concerns in the first trimester of primiparous women can make the diagnosis of prenatal anxiety very difficult (20). Another complex diagnostic problem is the comorbidity between anxiety and depression, with many symptoms being similar in anxiety and depression (21). However, perinatal anxiety is more common in the postpartum period than in pregnancy, with a frequency ranging from 6.1% to 27.9% in the postpartum period (22). This high prevalence is due to the emotional deregulation from the function of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and can be mitigated by recent contact with infants (23). On the other hand, perinatal depression is depression that occurs during or after pregnancy. Symptoms vary from rare to severe but can be treated effectively. Perinatal depression is caused by a combination of environmental and genetic factors (13). In addition to personal and family history of depression, some other factors, including maternal anxiety, poor relationship quality, pregnancy complications and history of physical and sexual abuse, can contribute to perinatal depression (24). The prevalence of prenatal depression has averaged 10–25% (25). Postnatal depression most commonly occurs within six weeks after birth and affects about 6.5% to 20% of postpartum women. It occurs more commonly among mothers with premature infants and in adolescents (26).

Obsessive compulsive disorder affects 2% of pregnant women and 2-3% of postpartum women (within the first year) (27). Assessing a pregnant or postpartum woman involves a careful consideration of risks and an attentive communication and the purpose of therapy is to teach women to tolerate their symptoms and to develop the mother-infant bond (28).

Some women can develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during pregnancy. Women who re-experienced a past trauma or those who suffered from a new trauma during pregnancy may experience posttraumatic stress that can worsen in the postpartum period (29). The mean prevalence of prenatal PTSD is 3.3% (30). Various conditions seem to affect the development of PTSD in the perinatal period, including pregnancy complications, complications during childbirth, emergency cesarean section, atomic history of psychiatric disorders, fear of childbirth, and previous traumatic life events (31-33). A traumatic birth experience that evolves into PTSD can overshadow the mother-infant relationship, the relationship with the partner and the desire for another pregnancy in the future (34). The prevalence of postpartum PTSD varies between 4.6 to 16.8%, and, in some cases involving emergency surgeries, it may reach up to 30% (35).

Finally, postpartum psychosis is a very serious perinatal mental disorder that can affect women soon after delivery. It affects around 1 in 500 postpartum mothers (16). Women with a family or personal history of bipolar disorder run a higher risk of recurrence in this period. Also, the risk is higher if a pregnant woman with a bipolar disorder discontinued her medication (36). Other risk factors for postpartum psychosis include the extremes of reproductive age, primiparity cesarean section (37), poor socioeconomic status and postpartum maternal and neonatal complications (38).

1. Support from the partner

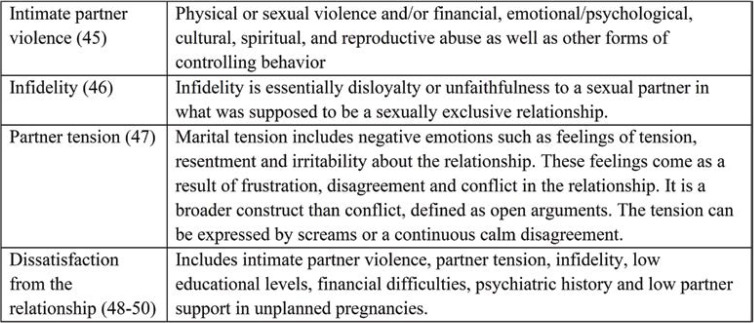

By the term "partner support" we mean all supportive mental and behavioral actions that a partner offers to the problems faced by the partner in a relationship (39). The fact that the support from a partner is considered the most important source of help during the perinatal period is not arbitrary. So far, many studies support the role of social support in the prevention and treatment of women's mental health problems during the perinatal period (40), but the mother's relationship with her partner is considered a more stronger protective factor than social support (41-43). It has been shown that intimacy resulting from a balanced relationship can promote mental and physical health. Thus, even in the case of women suffering from a mental illness, the support of a partner can minimize these symptoms (44). Severe perinatal mental health issues were a more frequent sign in women with low partner support. More specifically, intimate partner violence, partner infidelity or partner tension are factors of woman’s dissatisfaction with their relationship (Table 2).

1.1. Intimate violence during the perinatal period

Domestic violence is a physical, sexual or emotional abuse by an intimate partner (51). However, it has been shown that the high prevalence of perinatal depression (52), anxiety and PTSD is associated with intimate partner violence experiences (53). Some studies have reported that women who had experienced prenatal stress were more likely to have experienced violence from their partner compared to those without anxiety symptoms (54). Also, in a study conducted in Bangladesh, 7 in 10 pregnant women reported being the victim of at least a single act of physical violence from the partner, while the prevalence of antenatal anxiety and antenatal depression was 29.4% and 18.3%, respectively (50). It is a fact that intimate partner violence is a risk factor for postpartum mental health problems. In a study published in 2014 (55), almost two thirds of postpartum women who showed serious mental health issues reported intimate partner violence during pregnancy. In addition, a systematic review of Paulson, published in 2020, reported that the intimate partner violence was largely associated with perinatal depression and PTSD. Outcomes were more severe for women when the intimate partner violence occurred during the perinatal period (56). Regarding the causes associated with perinatal partner violence, several issues might be responsible for such incidences, including suspicion about the newborn or preference for a male sex of the child, alcohol consumptions, partner infidelity, lower educational level and financial difficulties (57).

1.2. Partner infidelity

Another indicator of the quality stability is the absence of infidelity. Few studies have been conducted on the effect of partner infidelity on maternal depressive symptoms during the perinatal period. One qualitative study published in 2014 (58) highlighted that partner rejection and infidelity were possible causes of maternal perinatal mental disorders, while a study of Fisher et al from 2012 (10) had reported that polygamous relationships resulted in more symptoms of perinatal mental disorders in mothers. In addition, jealousy was considered as a major factor of abusive relationships and may be a consequence of partner’s infidelity. Similarly, partner infidelity can also lead to intimate partner violence (57).

1.3. Partner tension

Partner tension is considered as a predictor factor of anxiety and depression in women during the perinatal period and poor quality of a relationship, according to the study of Bayrampour et al (2015) (59). In the research of postpartum depression and the relationship with a partner, all fathers reported some communication problems and an increase of their tension. Tension sometimes came from differing communication styles, while the role transitions during the perinatal period contributed to the deterioration of the problem (60).

2. Other factors that contribute to dissatisfaction from the relationship

Various studies have correlated the couple's socioeconomic status and symptoms of maternal depression, anxiety and PTSD during the perinatal period (3, 10, 61-63). However, other studies did not find any correlation between the above variables (64, 65). In fact, the balance in a relationship can be upset due to financial difficulties (49), while other factors, including low educational level (49, 66), history of mental health problems (50, 59), younger age (67) as well as unwanted pregnancies (68), can be contributors to perinatal mental health problems (69). When the partner is not supportive during the perinatal period, the above factors increase the chances of women being dissatisfied with their relationship.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSIONS

The aim of this study was to investigate the support from the partner and its impact on maternal perinatal mental health outcomes. As seen above, the relationship with the partner is catalytic in the development and consolidation of perinatal mental disorders. Therefore, a non-supportive partner will not be able to offer support neither to the mother during the prenatal period nor to himself during the postpartum period (70). Severe perinatal mental health problems were a more common sign or may more easily recur in women with low partner support. More specifically, partners of women with postpartum psychosis should be hypervigilance for signs of relapse or positive changes in a woman's attitudes and behavior (71). On the other hand, postpartum PTSD is related to low couple relationship satisfaction, even when controlling for a considerable number of background factors (72). In terms of support for postpartum depression, a significant reduction in symptoms has been observed in women who received support from their partner, in contrast to those who did not have support and experienced a worsening of their depressive symptoms (73). However, a cross-sectional study published by Nasreen in 2011 (50) showed that 18% of women had depressive symptoms and 29% anxiety symptoms during pregnancy, which were associated with low partner support, including intimate partner violence, in combination with other factors such as the interaction between poor household economy and poor partner relationship.

Of course, intimate partner violence, partner infidelity and partner tension are major factors of relationship dissatisfaction. In addition to the above problems in a relationship, the role of other factors, such as financial difficulties, low educational levels, psychiatric history, younger age and unplanned or unwanted pregnancies can be a link between all causes of dissatisfaction with the partner. However, the high quality of perinatal support from the partner can contribute to the improvement of mothers’ health but also of the newborn’s and, consequently, the child’s health (11). Finally, the World Health Organization (74) has recommended that health policies on maternal mental health problems should emphasize the importance of early screening for perinatal mental health problems, perinatal care and implications for training.

Instructions to perinatal care professionals

We believe that the current study will help develop a more thorough understanding of the impact that the support or non-support from a partner can have on women. For this reason, early detection of couples’ relationship problems during the perinatal period and the provision of professional help, particularly in high-risk couples, may not only improve the quality of the couple’s relationship but also favour positive perinatal experiences, positive perinatal mental health outcomes, development of strong bond mother-child and therefore, positive effects on infant and child health.

Finally, it is imperative to establish health policies on mental health, especially perinatal mental health, which should focus on the importance of early diagnosis of perinatal mental disorders, good midwifery practices and perinatal training.

Conflict of interests: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Maria Gianoutsou for her important help regarding English editing.

TABLE 1.

Perinatal mental disorders and their symptoms

TABLE 2.

Low partner support

Contributor Information

Evangelia ANTONIOU, Department of Midwifery, University of West Attica, 12243 Athens, Greece.

Maria-Dalida TZANOULINOU, Department of Midwifery, University of West Attica, 12243 Athens, Greece.

Pinelopi STAMOULOU, Department of Midwifery, University of West Attica, 12243 Athens, Greece.

Eirini OROVOU, Department of Midwifery, University of West Attica, 12243 Athens, Greece.

References

- 1.Pilkington P, Milne L, Cairns K, Whelan T. Enhancing Reciprocal Partner Support to Prevent Perinatal Depression and Anxiety: A Delphi Consensus Study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:23. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0721-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Zee-van den Berg AI, Boere-Boonekamp MM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn C, et al. Postpartum Depression and Anxiety: A Community-Based Study on Risk Factors before, during and after Pregnancy. J Affect Disord. 2021;286:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth Induced Posttraumatic Stress Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Risk Factors. Front Psychol. 2017;8:560. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hara MW, Wisner KL. Perinatal Mental Illness: Definition, Description and Aetiology. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2014;28:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia ER, Yim IS. A Systematic Review of Concepts Related to Women’s Empowerment in the Perinatal Period and Their Associations with Perinatal Depressive Symptoms and Premature Birth. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2017;17:347. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1495-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, et al. Prevalence and Determinants of Common Perinatal Mental Disorders in Women in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2012;90:139–149. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.091850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stapleton LRT, Schetter CD, Westling E, et al. Perceived Partner Support in Pregnancy Predicts Lower Maternal and Infant Distress. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26:453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0028332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George A, Luz RF, De Tychey C, et al. Anxiety Symptoms and Coping Strategies in the Perinatal Period. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2013;13:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a Measure of Postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard, L. M.; Khalifeh, H. Perinatal Mental Health: A Review of Progress and Challenges. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:313–327. doi: 10.1002/wps.20769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Wulff M, et al. Implications of Antenatal Depression and Anxiety for Obstetric Outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:467–476. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000135277.04565.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, Swift E. Perinatal Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Assessment and Treatment. J Womens Health. 2015;24:762–770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weisberg RB, Paquette JA. Screening and Treatment of Anxiety Disorders in Pregnant and Lactating Women. Women’s Health Issues. 2002;12:32–36. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(01)00140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wardrop AA, Popadiuk NE. Women’s Experiences with Postpartum Anxiety: Expectations, Relationships, and Sociocultural Influences. Qualitative Report. 2013;18:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali E. Women’s Experiences with Postpartum Anxiety Disorders: A Narrative Literature Review. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:237–249. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S158621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lonstein JS. Regulation of Anxiety during the Postpartum Period. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2007;28:115–141. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Accortt EE, Cheadle ACD, Dunkel Schetter C. Prenatal Depression and Adverse Birth Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1306–1337. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1637-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell EJ, Fawcett JM, Mazmanian D. Risk of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Pregnant and Postpartum Women: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:377–385. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muzik M, McGinnis EW, Bocknek E, et al. PTSD Symptoms across Pregnancy and Early Postpartum Among Women with Lifetime PTSD Diagnosis. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:584–591. doi: 10.1002/da.22465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yildiz PD, Ayers S, Phillips L. The Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Pregnancy and after Birth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:634–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sentilhes L, Maillard F, Brun S, et al. Risk Factors for Chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Development One Year after Vaginal Delivery: A Prospective, Observational Study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8724. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09314-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Heumen MA, Hollander MH, van Pampus MG, et al. Psychosocial Predictors of Postpartum Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Women With a Traumatic Childbirth Experience. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:348. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James S. Women’s Experiences of Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after Traumatic Childbirth: A Review and Critical Appraisal. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18:761–771. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0560-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaban Z, Dolatian M, Shams J, et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Following Childbirth: Prevalence and Contributing Factors. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:177–182. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orovou E, Dagla M, Iatrakis G, et al. Correlation between Kind of Cesarean Section and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Greek Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17:1592. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing Maternal Deaths to Make Motherhood Safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG. 2011;118 Suppl 1:1–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blackmore ER, Jones I, Doshi M, et al. Obstetric Variables Associated with Bipolar Affective Puerperal Psychosis. BJPsych. 2006;188:32–36. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Upadhyaya SK, Sharma A, Raval CM. Postpartum Psychosis: Risk Factors Identification. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:274–277. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.134373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haber MG, Cohen JL, Lucas T, Baltes BB. The Relationship between Self-Reported Received and Perceived Social Support: A Meta-Analytic Review. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39:133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng ER, Rifas-Shiman SL, Perkins ME, et al. The Influence of Antenatal Partner Support on Pregnancy Outcomes. J Womens Health. 2016;25:672–679. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowe HJ, Fisher JR. Development of a Universal Psycho-Educational Intervention to Prevent Common Postpartum Mental Disorders in Primiparous Women: A Multiple Method Approach. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:499. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hopkins J, Campbell SB. Development and Validation of a Scale to Assess Social Support in the Postpartum Period. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Highet NJ, Gemmill AW, Milgrom J. Depression in the Perinatal Period: Awareness, Attitudes and Knowledge in the Australian Population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:223–231. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.547842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edwards RC, Thullen MJ, Isarowong N, et al. Supportive Relationships and the Trajectory of Depressive Symptoms among Young, African American Mothers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:585–594. doi: 10.1037/a0029053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Birditt KS, Wan W, Orbuch T, Antonucci T. The Development of Marital Tension: Implications for Divorce among Married Couples. Dev Psychol. 2017;53:1995–2006. doi: 10.1037/dev0000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernard O, Gibson RC, McCaw-Binns A, et al. Antenatal Depressive Symptoms in Jamaica Associated with Limited Perceived Partner and Other Social Support: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jonsdottir SS, Thome M, Steingrimsdottir T, et al. Partner Relationship, Social Support and Perinatal Distress among Pregnant Icelandic Women. Women and Birth. 2017;30:e46–e55. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nasreen HE, Kabir ZN, Forsell Y, Edhborg M. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms during Pregnancy: A Population Based Study in Rural Bangladesh. BMC Women’s Health. 2011;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Necho M, Belete A, Zenebe Y. The Association of Intimate Partner Violence with Postpartum Depression in Women during Their First Month Period of Giving Delivery in Health Centers at Dessie Town, 2019. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2020;19:59. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00310-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hahn CK, Gilmore AK, Aguayo RO, Rheingold AA. Perinatal Intimate Partner Violence. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45:535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jundt K, Haertl K, Knobbe A, et al. Pregnant Women after Physical and Sexual Abuse in Germany. GOI. 2009;68:82–87. doi: 10.1159/000215931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Desmarais SL, Pritchard A, Lowder EM, Janssen PA. Intimate Partner Abuse before and during Pregnancy as Risk Factors for Postpartum Mental Health Problems. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paulson JL. Intimate Partner Violence and Perinatal Post-Traumatic Stress and Depression Symptoms: A Systematic Review of Findings in Longitudinal Studies. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2020;28:1524838020976098. doi: 10.1177/1524838020976098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abota TL, Gashe FE, Kabeta ND. Postpartum Women’s Lived Experiences of Perinatal Intimate Partner Violence in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A Phenomenological Study Approach. IJWH. 2021;13:1103–1114. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S332545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kathree T, Selohilwe OM, Bhana A, Petersen I. Perceptions of Postnatal Depression and Health Care Needs in a South African Sample: The “Mental” in Maternal Health Care. BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14:140. doi: 10.1186/s12905-014-0140-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bayrampour H, McDonald S, Tough S. Risk Factors of Transient and Persistent Anxiety during Pregnancy. Midwifery. 2015;31:582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Battle CL, Londono Tobon A, Howard M, Miller IW. Father’s Perspectives on Family Relationships and Mental Health Treatment Participation in the Context of Maternal Postpartum Depression. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:4191. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.705655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, et al. Risk Factors for Depressive Symptoms during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stewart D. Perinatal Mental Health in Low- and Middle-Income Country Migrants. BJOG. 2017;124:753–753. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rondon MB. Perinatal Mental Health around the World: Priorities for Research and Service Development in South America. BJPsych International. 2020;17:85–87. doi: 10.1192/bji.2020.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abuidhail J, Abujilban S. Characteristics of Jordanian Depressed Pregnant Women: A Comparison Study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2014;21:573–579. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Srinivasan N, Murthy S, Singh AK, et al. Assessment of Burden of Depression During Pregnancy Among Pregnant Women Residing in Rural Setting of Chennai. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:LC08–LC12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12380.5850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yanikkerem E, Ay S, Mutlu S, Goker A. Antenatal Depression: Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Hospital Based Turkish Sample. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63:472–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, et al. Depressed Mood in Pregnancy: Prevalence and Correlates in Two Cape Town Peri-Urban Settlements. Reproductive Health. 2011;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kazemi A, Ghaedrahmati M, Kheirabadi G. Partner’s Emotional Reaction to Pregnancy Mediates the Relationship between Pregnancy Planning and Prenatal Mental Health. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2021;21:168. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-03644-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garthus-Niegel S, Ayers S, Martini J, et al. The Impact of Postpartum Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms on Child Development: A Population-Based, 2-Year Follow-up Study. Psychol Med. 2017;47:161–170. doi: 10.1017/S003329171600235X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sapkota S, Kobayashi T, Takase M. Impact on Perceived Postnatal Support, Maternal Anxiety and Symptoms of Depression in New Mothers in Nepal When Their Husbands Provide Continuous Support during Labour. Midwifery. 2013;29:1264–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Holford N, Channon S, Heron J, Jones I. The Impact of Postpartum Psychosis on Partners. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:414. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2055-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A, Handtke E, et al. The Impact of Postpartum Posttraumatic Stress and Depression Symptoms on Couples’ Relationship Satisfaction: A Population-Based Prospective Study. F. rontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:1728. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Misri S, Kostaras X, Fox D, Kostaras D. The Impact of Partner Support in the Treatment of Postpartum Depression. Can J Psychiatry. 2000;45:554–558. doi: 10.1177/070674370004500607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]