Abstract

Introduction:Care delivery from nursing staff to patients in hospital environment may involve the exertion of considerable muscular force and, as a result, there is a consequent risk of developing musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). The aim of this prospective study was to investigate the relationship between reported MSDs and perceived caring behaviors among nursing staff.

Methods: A total of 250 questionnaires were completed in three Greek hospitals during February and March 2019. The Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire for the evaluation of MSDs and the Caring Behaviors Inventory-24 (CBI-24) for the assessment of caring behaviors were used.

Results:A total of 185 participants (74%) were found to have at least one MSD. Back (64.3%), neck (63.2%) and shoulder (58.4%) pain were the most commonly reported MSDs. The mean score on the CBI-24 scale was 5.06 (SD=0.51) and the mean “Connectedness” dimension was 4.59 (SD=0.74). Elbow MSDs were significantly associated with the lowest score in the “Knowledge and skills” dimension (p=0.024) and the lowest overall nursing score (p=0.048). Linear regression analysis showed that the lowest nursing care score was associated with left-handed nurses (p=0.008) of low hierarchical position (p=0.013), suffering from elbow MSDs (p=0.002), for which they did not seek treatment (p=0.023). Participants who continued to work on a regular basis despite MSDs showed a lower score on the dimensions of “Respectful” (p=0.05) and “Connectedness” (p=0.01).

Conclusion:The nursing staff showed high percentage of MSDs that negatively affected their perceived dimensions of caring behaviors. These findings could be used to prevent and deal with work-related MSDs, reduce occupational hazards and improve hospital patient care.

Keywords:musculoskeletal disorders, nursing staff, caring behaviors, Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire, Caring Behaviors Inventory-24.

INTRODUCTION

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) represent a common health problem for nursing staff due to the nature of nursing. The most commonly reported sites for MSDs are the lower back, neck and shoulders (1, 2). Musculoskeletal disorders often significantly affect nurses’ quality of life and may lead to job restrictions, absenteeism and desire to leave the profession (3, 4). In addition, MSDs affect nurses’ productivity and caring behaviors, which may lead to decrease of the quality-of-care provision, patient satisfaction as well as safety (5, 6).

Understanding nurses’ perceptions of caring behaviors is crucial, since nurses represent the primary caregivers in the healthcare system and are among the first healthcare providers to interact with patients. The experiences and working conditions of nursing staff and methods for the division of labor may significantly affect caring behaviors (7).

The aim of this prospective study was to investigate the relationship between the reported MSDs and the caring behaviors of nurses and nursing assistants in three general hospitals.

METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted in various departments of three Greek hospitals (“Sismanoglio” General Hospital, “Amalia Fleming” General Hospital, 417 Army Equity Fund Hospital) in the region of Attica between February and March 2019. Of the 266 people who met the inclusion criteria (must have worked as clinical nurses or nursing assistants for at least one year), 250 participated in the study (69.5%). The Greek version of the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire was used to record possible MSDs, classified as pain, discomfort or numbness in specific anatomical areas (8-10). The Greek version of the Caring Behavior Inventory-24 (CBI-24) Questionnaire was used to assess behaviors and the overall quality of care (11, 12). It consists of four subgroups and 24 items representative of different caring behaviors (13). Demographic and occupational data were also recorded as well as information about participants’ lifestyles and overall perceptions of health.

Mean values, standard deviations (SD), median and interquartile ranges (IQR) were used to describe the quantitative variables. Absolute (N) and relative (%) frequencies were used to describe the qualitative variables. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney criterion was used to compare quantitative variables. Linear regression analysis was used to determine independent factors related to the dimensions of nursing care from which dependent coefficients (b) and their standard errors (SE) emerged, while logistic regression analysis, following the consecutive integration/ subtraction procedure, was used to find independent factors related to the presence of discomfort. Statistical significance was set at 0.05. Data were analyzed using the SPSS v.24.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) statistical package for personal computers.

The study was approved by the relevant committees of all three institutions and written informed consent was received form all participants.

RESULTS

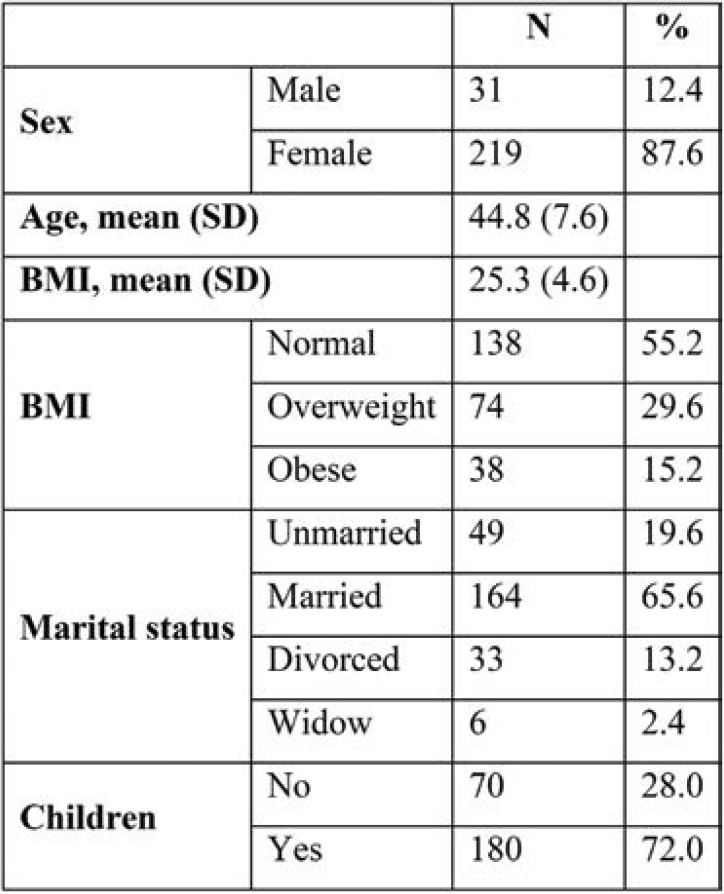

A total of 250 nurses and nursing assistants were enrolled in the study. The studied population had a mean age of 44.8 years (SD=7.6) and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 25.3 kg/m2 (SD=4.6). Among all participants, 87.6% were females, 65.6% were married and 72.0% had children (Table 1).

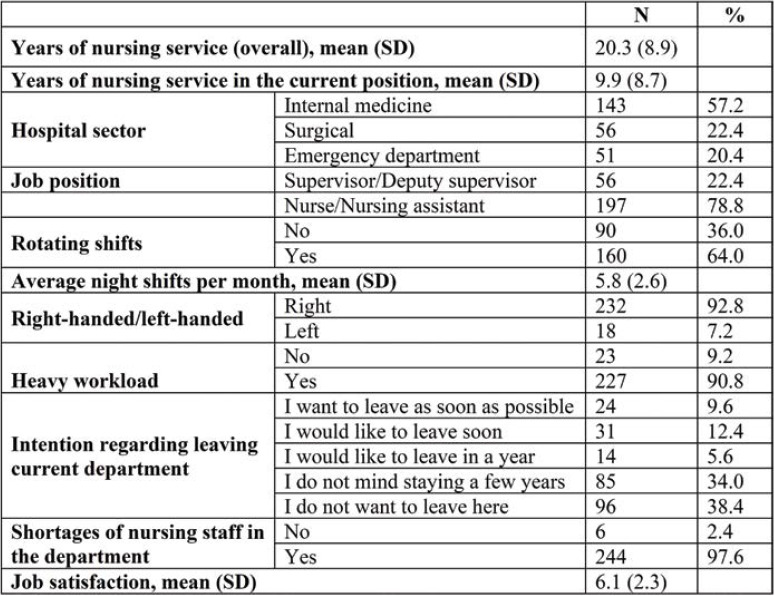

The participants’ mean total nursing service was 20.3 years (SD=8.9) and the average nursing service in the current position 9.9 years (SD=8.7). Among all subjects, 64.0% worked part-time and 57.2% had a job in the internal medicine sector. A total of 90.8% of participants reported large nursing workload and 97.6% shortages of nursing staff in their department, while 38.4% of all subjects did not want to leave their current department. The average work satisfaction score (10-point scale) was 6.1 (SD=2.3) (Table 2).

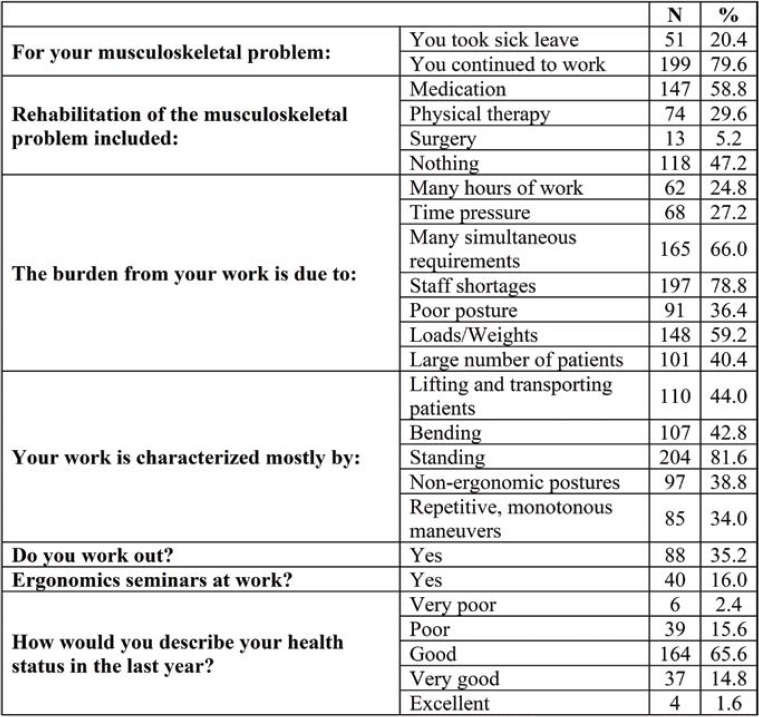

Among participants who experienced MSDs (n=185, 74%), 79.6% continued to work, while 58.8% had received mainly medication and 29.6% physiotherapy. The main reasons for a higher nursing workload included staff shortages and many simultaneous requirements (78.8% and 66.0%, respectively). Regarding ergonomics, 81.6% of all subjects reported a lot of standing in their work, while 35.2% exercised regularly and 16.0% had taken ergonomics seminars at work. The majority of participants (65.6%) described their health condition as “good” (Table 3).

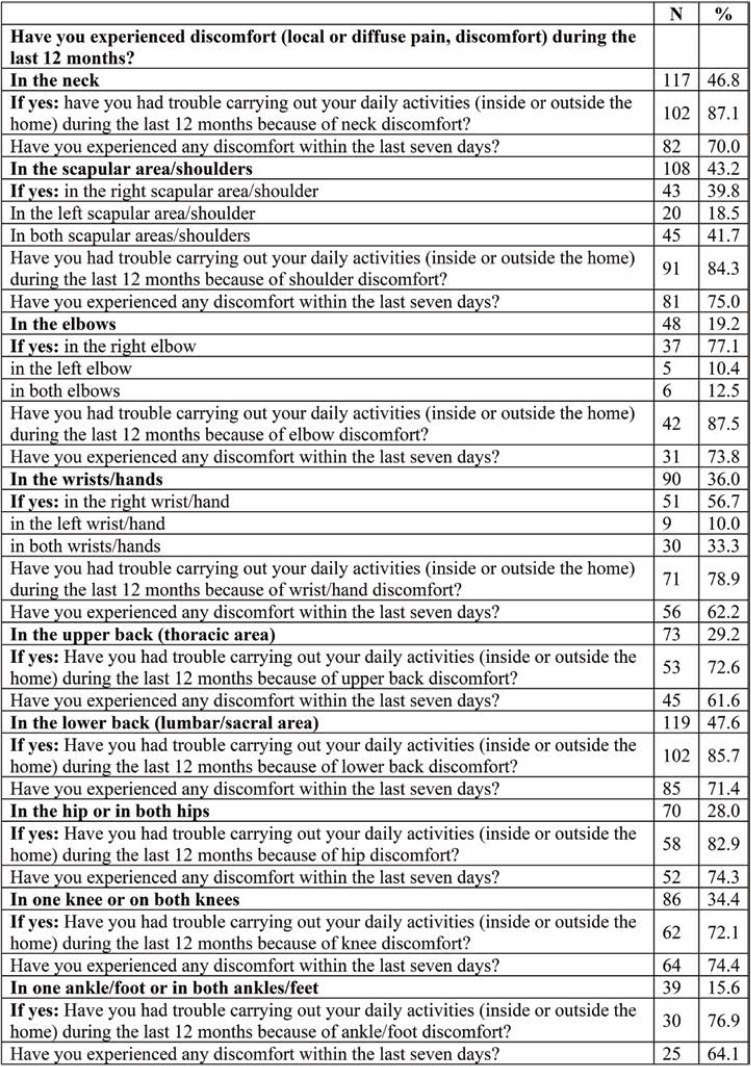

Musculoskeletal disorders reported in the last year were mainly in the lower back (47.6%), neck (46.8%) and shoulder/scapular areas (43.2%) (Table 4).

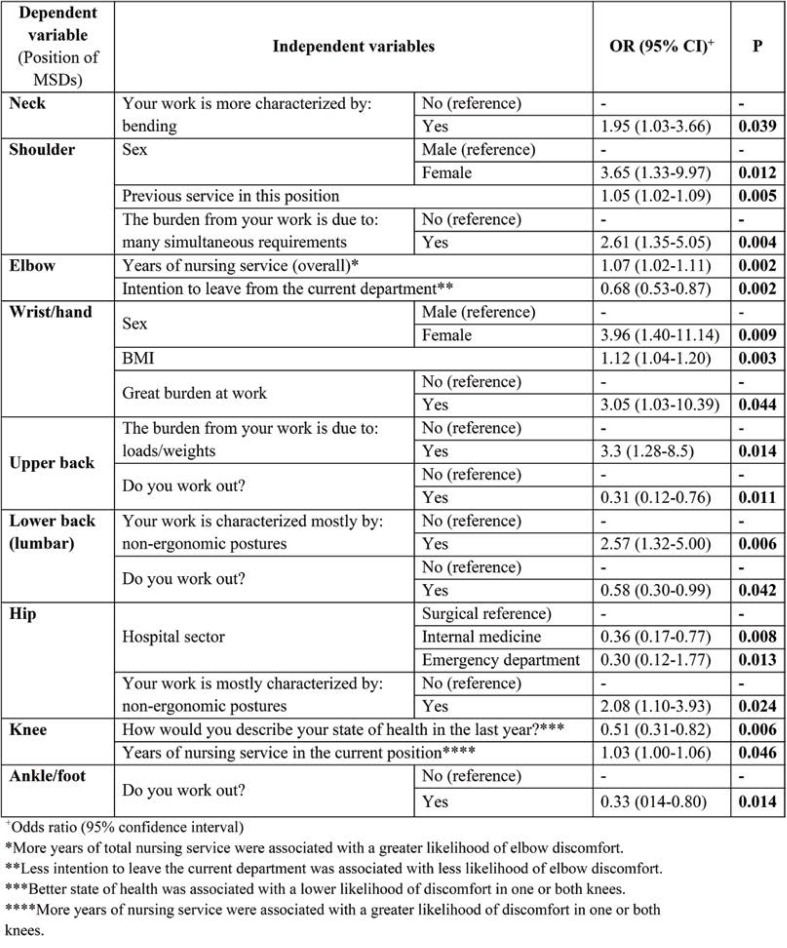

Multifactorial logarithmic regressions results are shown in Table 5. Participants who frequently needed to bend at work were 1.95 times more likely to have neck discomfort. Women (3.65 times), previous service in this position and those reporting a heavy work burden due to many simultaneous requirements (2.61 times) reported more discomfort in the shoulder/scapular areas.

Nurses with more work experience presented more elbow discomfort (1.07 times), while a lesser desire to leave the workplace was associated with less elbow discomfort.

Females (3.96 times), those with higher BMI (1.12 times) and those reporting a heavy work burden (3.05 times) were more likely to have wrist/hand discomfort.

Participants reporting a work burden due to loads/weights (3.30 times) were more likely to have discomfort in the upper back, while participants who exercised were less likely to have discomfort in the upper back (69%).

Those reporting non-ergonomic work postures were more likely (2.57 times) to have lower back discomfort, while those who exercised were less likely to have lower back discomfort (42%). Employees in the internal medicine sector and Emergency Department were less likely to have discomfort in one or both hips (64% and 70% less likely, respectively), while those reporting non-ergonomic work postures were 2.08 times more likely to have discomfort in one or both hips.

Those who reported better health and those with more years of nursing service in the current position were less likely to have knee problems. Finally, participants who exercised were less likely to have discomfort in one or both ankles/legs.

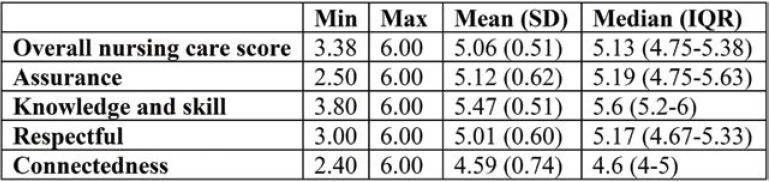

The scores on the “overall nursing care score” of the CBI-24 questionnaire ranged from 3.38 to 6, with a mean value of 5.06 (SD=0.51). The highest score was found in the “Professional knowledge and skills” dimension, with a mean value of 5.47 (SD=0.51), while the lowest score was reported in the “Positive connectedness” dimension, with a mean value of 4.59 (SD=0.74) (Table 6).

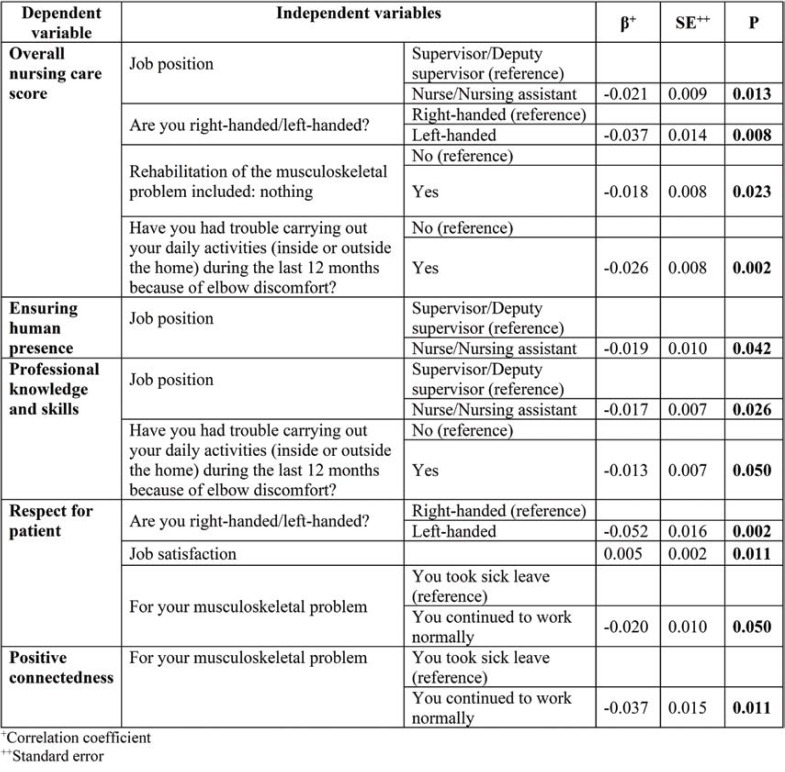

Multifactorial linear regression was also performed, as shown in Table 7. Job position, lefthandedness, following a rehabilitation method and elbow discomfort were found to be related to the overall nursing care score. Significantly lower scores were reported by clinical nurses/nursing assistants, left-handers, those not following any rehabilitation method for their MSDs and those reporting elbow discomfort.

Job position was the only factor found to be significantly related to the score in the “Assurance” dimension, with clinical nurses/nursing assistants showing significantly lower scores compared to supervisors/deputy supervisors.

Job position and elbow discomfort were related to the score in the “Knowledge and skills” dimension. In particular, clinical nurses/nursing assistants had significantly lower scores, compared with supervisors/deputy supervisors, as did those who reported elbow discomfort.

Left-handedness, job satisfaction, and following a rehabilitation method were found to be related to the “Respectful” dimension. In particular, left-handers, those reporting less work satisfaction and subjects who continued to work despite their musculoskeletal problems had significantly lower scores.

Following a rehabilitation method was found to be significantly related to the “Connectedness” score, with participants who continued to work despite their MSDs showing significantly lower scores compared to participants who took sick leave.

DISCUSSION

The nurses and nursing assistants from three Greek hospitals participating in this prospective study reported a high percentage of MSDs in the lower back, neck, shoulders and scapular area during the previous year. A correlation was found between the location of MSDs and demographic and occupational data such as gender, hospital sector, years of service, physical activity, BMI and work burden.

Similar research has found that high BMI, more years of service and older age are associated with the onset of MSDs (3, 14). Nurses with a higher BMI are much more likely to report upper extremity discomfort, while nurses with more than 20 years of clinical service are approximately four times more likely to develop MSDs than those with 11 to 20 years of service (15, 16).

In the present study, no correlation was found between MSDs and marital status or working hours. However, MSDs appear to be more common among married nurses, and more severe among nurses working part-time (4, 17).

This study also revealed that the mean job satisfaction score was low and the majority of participants reported shortages of nursing staff in the department where they were working. These shortages in combination with the numerous daily tasks and frequent heavy lifting were the main reasons for the heavy work burden and the desire to move in another department. Heavy work burden and shortages of nursing staff appear to be associated with an increased risk of burnout, MSDs and dissatisfaction as well as medical/nursing errors (18, 19). It also caused low job satisfaction, deterioration in the quality of life, increased stress, tendency to absenteeism, and a greater desire to change position or leave the profession (3, 20, 21).

Many participants with MSDs continued to work normally despite the presence of MSDs, a situation also observed in the study by Amin et al (15). The possible causes of this phenomenon include ethical reasons (concern for colleagues’ increased workload), financial reasons (fear of dismissal), work arrangements (avoidance of certain activities) or other reasons such as better placement in the department’s hierarchy (18, 22-24). Some nurses consider MSDs an inevitable consequence of the nature of their work. However, the tendency of nurses to continue working despite their discomfort may worsen or complicate the recovery from MSDs, adversely affecting their work performance (25). A large proportion of participants reported a good health, a finding that, combined with the low rate of sick leave attributable to MSDs, may indicate either a low morbidity or the fact that the presence of MSD does not automatically imply a poor health status.

The majority of participants reported moderate physical activity, which is in line with other studies (26, 27). Low physical activity can be associated with health problems and injuries, while regular physical activity improves muscle tone, keeps the musculoskeletal system in good condition, reduces MSD symptoms and improves the psychosocial status (27, 28).

A very small percentage of participants in the present study had attended ergonomics seminars. Injury prevention training and ergonomics interventions may help in preventing as well as treating MSDs. However, their importance is often underestimated, resulting in reduced performance and diminished desire to stay at work despite the contradictory research outcomes regarding the effectiveness of training interventions and assistive devices (3, 4, 29, 30).

The studied population reported high rates (nearly 50%) of MSDs in the lower back, neck and shoulder area. These areas are quite typical, according to other relevant studies (1, 2). Symptoms in the back, especially in the lower back region, are more often present in nurses performing repeated invasive procedures, health and comfort care procedures, feeding and mobilization of bedridden patients (31). Neck MSDs are associated with high workload, demanding postures (especially torso flexion), low satisfaction rates and low levels of control at work (32-34).

Shoulder MSDs were significantly correlated with female sex, multiple and simultaneous work requirements, and more years of nursing service in the current position. Low levels of work control, repetitive tasks and limited autonomy increase the risk of developing MSDs in women (35, 36). Length of previous service and older age may be related to neck and shoulder MSDs, while age may also be related to years of service, correlations that could explain that nurses tend to take on patients with more care needs and the cumulative effects of long-term injuries to them in their work environment (37, 38).

In the present study it was found that elbow MSDs were significantly related to the desire to change department in the workplace. These findings had been previously reported in a study by Freimann et al (39). In addition, elbow MSDs were significantly related to the overall years of nursing. Female participants, nurses with higher BMIs and those who reported a high burden at work reported significantly more MSDs in the wrists. Also, a positive correlation has been found between higher BMI values and the frequency of MSDs in the upper back, shoulders and lower back, while wrist MSDs have been associated with higher BMI and female sex (40, 41). Musculoskeletal disorders in the upper back were related to the work burden due to physical loads and weights and to the levels of physical exercise. Similarly, these MSDs have been found to be associated with heavy physical work and frequently demanding postures (25). It has been also reported that nurses had a worse physical condition compared to the general population; this, in combination with the increased physical demands of their profession, increased the risk of developing MSDs (42, 43). Regular participation in sports was reported to reduce the risk of neck and shoulder symptoms (44), while mild exercise had a protective effect against low back and neck pain in workers with heavy and sedentary activities (45-46).

Low back pain has been found to be associated with non-ergonomic postures and a lack of exercise. In general, low back MSDs appear to be associated with heavy lifting, changing a patient’s position, prolonged standing, high workload, working in a surgical sector and poor job satisfaction (3, 47). Implementing a zero-lift program in hospitals in Washington in order to prevent lumbar injuries in health workers has resulted in significant reduction of MSDs (48).

Hip MSDs were found to be related to work department and non-ergonomic postures, with nurses in the surgical sector reporting higher incidence. Nursing staff in the Intensive Care Unit also appears to be at greater risk of developing MSDs compared to their older counterparts working in other departments, because of the greater effort involved in delivering patient care (49). Similarly, nurses in the surgical sector are at greater risk of developing MSDs compared to their older counterparts working in other departments, as a result of additional physical risk factors (3).

Knee MSDs were found to be related to participants’ health status and years of work. Other factors associated with the occurrence of these MSDs in nurses included low job satisfaction and older age (1, 32, 50).

Participants who exercised were 67% less likely to develop ankle/foot MSDs. Nurses with a poorer physical health were six times more likely to have limited ankle/foot disorders, while strenuous walking and standing contributed to ankle/ foot MSDs (47, 51). Regular physical activity had a protective effect and reduced the risk of developing MSDs (52). Moreover, the physical and psychological demands of work are significantly related to nurses’ MSDs, and it is advisable that intervention programs should be implemented (53).

The mean value of the overall Nursing Care Score in the present study was 5.06. A lower value of 4.21 ± 1.08 was reported by a study conducted in Ethiopia, while a higher value (5.54 ± 0.53) was found in another study of 1500 clinical nurses, after the application of a professional model of nursing care and practice (54, 55).

According to Porter et al, the highest scores were seen in the “Knowledge and skills” dimension and the lowest in the “Connectedness” dimension, with the same hierarchy and classification of the dimensions of care behaviors (55). Similarly, Sarafis et al reported that the highest score in caring behaviors regarded the dimension of “Knowledge and skills”, followed by that of “Assurance” and “Respectful”, which probably suggests that nurses valued clinical knowledge and skills as the most important (56). However, the psychosocial aspects of care, especially patient communication, seem to contribute more to improving patient satisfaction (11).

Differences between patients and nurses’ perceptions of caring behaviors are common (57). Nurses tend to rate themselves higher than their patients do. They feel more reassuring and positively connected than their patients perceive them to be, while nurses also believe that they are better in terms of skills, knowledge and respect for others compared to their patients’ evaluation (5).

Consistently with findings from other studies using CBI-24, the lowest score was observed in the “Connectedness” dimension, which is described as the provision of continuous patient support with constant readiness and constant nurse presence (56, 58). These findings may be related to increased workload as well as understaffing of the reference hospitals. Time pressure is an important factor in nurses’ exhaustion, and it is significantly related to two components of burnout, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while perceived increased time pressure is reported to lead to more frequent depersonalization in nurses (59, 60). Time allocation contributes to positive patient development, while time pressure significantly reduces the quality of nursing care (61).

“Connectedness” was also associated with the presence of nurses at work despite the presence of MSDs. Nurses are ranked among the occupations with the highest rates of attendance at work despite health problems, while they often suffer from some chronic diseases associated with MSDs (6). However, not taking sick leave may make nurses more vulnerable and impatient, rendering them less able to fully meet the demands of their job (6, 54). The score in the “Respectful” dimension was correlated with the presence of nurses at work despite the occurrence of MSDs, with low job satisfaction and lefthandedness. However, dissatisfied nurses are more likely to distance themselves from their patients and generally provide lower-quality nursing care (62).

The low overall Nursing Care Score was significantly associated with left-handedness, nonsupervisor job position and failure to follow rehabilitation for elbow MSDs. Work experience and working conditions also affect caring behaviors, as do labor division methods (7, 58).

The correlation between low scores for caring behaviors and failure to follow rehabilitation for MSDs may indicate a corresponding life attitude or a matter of emotional intelligence, as higher emotional intelligence is associated with better self-control and consequently better services provided to the patient (63). The dimensions of “Assurance” and “Knowledge and skills” were found to be higher in nursing supervisors, probably because they have fewer clinical duties and more voluntary time to communicate with patients. In contrast, the high workload and additional clinical tasks of non-supervisor nurses may cause fatigue and irritability (64). In jobs with higher mental involvement and autonomy but lower physical strain, work ability remains stable and nursing supervisors often enjoy these benefits due to their age and professional development (65). In addition, older nurses may seek stability and achieve better adaptation to the work environment, while more work experience increases nurses’ sense of security, skills and opportunities for advancement and professional development (66, 67). Finally, nursing supervisors seem to develop professional skills and values through socialization (68).

Regarding the dimension of “Knowledge and skills”, correlation was found between job position and elbow MSDs. Low educational level and inadequate training have also been found to be associated with fewer career prospects, affecting work ability (3, 56). Additionally, elbow MSDs were significantly associated with low score in the “Knowledge and skills” dimension and low overall score on the CBI-24 scale. Another study found that nurses’ MSDs affected their productivity (6). Having a chronic health problem represents a low productivity predictor. Attending work with MSDs is associated with higher incidence of medication errors and lower self-reported quality of care. The effects of nurses’ poor health status on productivity are significant and are expected to be more unfavorable as the mean age of the nursing staff increases. There are also concerns regarding the potential adverse effects of certain narcotic analgesics used to treat nurses’ MSDs, which may cause drowsiness and decrease critical ability (6). Furthermore, higherranking job positions as well as older age are associated with lower risk of MSDs for nurses, given their fewer manual and more administrative tasks.

The present study has some limitations. The participation of nurses and nursing assistants from only one health district, differences in duties related to educational level and differences in staffing levels between hospitals as well as the inability to record the cause of absence from work may have affected the results of this study. More studies with larger and more representative samples are needed to investigate the prevalence of MSDs in nurses and nursing assistants and their association with caring behaviors.

The findings of the present study indicate that there are increased psychosocial risk factors that predispose to MSDs. The above data, combined with the fact that job satisfaction was not high and a significant percentage of participants expressed the desire to leave their profession showed that there was room for improvement in working conditions. At a time when it is imperative to explore all possible ways to improve the quality of care and reduce costs, prevention of MSDs in nursing staff is essential. Early identification of risk factors in the development of MSDs in the local working environment and the modification of working conditions, with ergonomic workplace design, as well as introduction of ergonomics programs and safe moving of patients will contribute towards maintaining the ability of nurses at a satisfactory level. A systematic investigation of caring behavior subcategories is also required, so that educational interventions and administrative support may be implemented.

Compliance with ethical standards: The study has been approved by the institutions’ bioethics committee.

Conflict of interests: none declared

Financial support: none declared.

Authors’ contributions: SN, PM, KR for the literature search and analysis, and manuscript writing. MS, IK, PS for data collection. SN, CK, OG, TK for concept. PM, MS, IK, PS, OG for data analysis. CK, OG, TK for the final manuscript revision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of study participants

TABLE 2.

Participants’ work-related data

TABLE 3.

Data on participants’ health status

TABLE 4.

Distribution of musculoskeletal disorders in nursing staff during the last year

TABLE 5.

Correlations of the existence of musculoskeletal disorders with demographic and occupational characteristics

TABLE 6.

Scores for caring behaviors (overall and individual dimensions)

TABLE 7.

Factors associated with CBI-24 dimensions

Contributor Information

Symeon NAOUM, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, “251” Air Force General Hospital of Athens, Greece.

Panagiotis MITSEAS, Department of Social Sciences, Hellenic Open University, Achaia, Patras, Greece.

Christos KOUTSERIMPAS, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, “251” Air Force General Hospital of Athens, Greece.

Maria SPINTHOURI, Department of Nursing, Venizeleio Pananeio General Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Ioannis KALOMIKERAKIS, Department of Nursing, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece.

Konstantinos RAPTIS, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, “251” Air Force General Hospital of Athens, Greece.

Pavlos SARAFIS, General Department Lamia, University of Thessaly, Greece.

Ourania GOVINA, Department of Nursing, University of West Attica, Greece.

Theocharis KONSTANTINIDIS, Department of Nursing, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Greece.

References

- 1.Freimann T, Pääsuke M, Merisalu E. Work-Related Psychosocial Factors and Mental Health Problems Associated with Musculoskeletal Pain in Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pain Res Manag. 2016;2016:9361016. doi: 10.1155/2016/9361016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexopoulos EC, Burdorf A, Kalokerinou A. Risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders among nursing personnel in Greek hospitals. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76:289–294. doi: 10.1007/s00420-003-0442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soylar P, Ozer A. Evaluation of the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in nurses: a systematic review. Med Sci. 2018;7:479–485. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rathore FA, Attique R, Asmaa Y. Prevalence and Perceptions of Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Hospital Nurses in Pakistan: A Cross-sectional Survey. Cureus. 2017;9:e1001. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiliç M, Öztunç G. Comparison of nursing care perceptions between patients who had surgical operation and nurses who provided care to those patients. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2015;8:625. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Letvak SA, Ruhm CJ, Gupta SN. Nurses' presenteeism and its effects on self-reported quality of care and costs. Am J Nurs. 2012;112:30–38. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000411176.15696.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salimi S, Azimpour A. Determinants of Nurses' Caring Behaviors (DNCB): Preliminary Validation of a Scale. J Caring Sci. 2013;2:269–278. doi: 10.5681/jcs.2013.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson AP, Steele EJ, Hodges PW, Stewart S. Development and test-retest reliability of an extended version of the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ-E): a screening instrument for musculoskeletal pain. J Pain. 2009;10:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonopoulou M, Ekdahl C, Sgantzos M, et al. Translation and standardisation into Greek of the standardised general Nordic questionnaire for the musculoskeletal symptoms. Eur J Gen Pract. 2004;10:33–34. doi: 10.3109/13814780409094226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer K, Smith G, Kellingray S, Cooper C. Repeatability and validity of an upper limb and neck discomfort questionnaire: the utility of the standardized Nordic questionnaire. Occup Med. 1999;49:171–175. doi: 10.1093/occmed/49.3.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf ZR. The caring concept and nurse identified caring behaviors. Top Clin Nurs. 1986;8:84–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papastavrou E, Karlou C, Tsangari H, et al. Cross-cultural validation and psychometric properties of the Greek version of the Caring Behaviors Inventory: a methodological study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:435–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Y, Larrabee JH, Putman HP. Caring Behaviors Inventory: a reduction of the 42-item instrument. Nurs Res. 2006;55:18–25. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heiden B, Weigl M, Angerer P, Müller A. Association of age and physical job demands with musculoskeletal disorders in nurses. Appl Ergon. 2013;44:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amin NA, Nordin R, Fatt QK, et al. Relationship between Psychosocial Risk Factors and Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Public Hospital Nurses in Malaysia. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2014;26:23. doi: 10.1186/s40557-014-0023-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tinubu BM, Mbada CE, Oyeyemi AL, Fabunmi AA. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among nurses in Ibadan, South-west Nigeria: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sveinsdóttir H. Self-assessed quality of sleep, occupational health, working environment, illness experience and job satisfaction of female nurses working different combination of shifts. Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20:229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brien K, Lukhele Z, Nhlapo JM, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in nurses working in South African spinal cord rehabilitation units. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2018;8:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holden RJ, Scanlon MC, Patel NR, et al. A human factors framework and study of the effect of nursing workload on patient safety and employee quality of working life. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:15–24. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2008.028381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacey SR, Cox KS, Lorfing KC, et al. Nursing support, workload, and intent to stay in Magnet, Magnet-aspiring, and non-Magnet hospitals. J Nurs Adm. 2007;37:199–205. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000266839.61931.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leone C, Bruyneel L, Anderson JE, et al. Work environment issues and intention-to-leave in Portuguese nurses: A cross-sectional study. Health Policy. 2015;119:1584–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ando S, Ono Y, Shimaoka M, et al. Associations of self estimated workloads with musculoskeletal symptoms among hospital nurses. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57:211–216. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coggon D, Ntani G, Vargas-Prada S, et al. Members of CUPID Collaboration. International variation in absence from work attributed to musculoskeletal illness: findings from the CUPID study. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:575–584. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-101316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rugulies R, Christensen KB, Borritz M, et al. The contribution of the psychosocial work environment to sickness absence in human service workers: results of a 3-year follow-up study. Work & Stress. 2007;21:293–311. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheung K, Szeto G, Lai GKB, Ching SSY. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Work-Related Musculoskeletal Symptoms in Nursing Assistants Working in Nursing Homes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:265. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsekoura M, Koufogianni A, Billis E, Tsepis E. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among female and male nursing personnel in Greece. World J Res Rev (WJRR) 2017;3:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heidari M, Borujeni MG, Khosravizad M. Health-promoting Lifestyles of Nurses and Its Association with Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Lifestyle Med. 2018;8:72–78. doi: 10.15280/jlm.2018.8.2.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yip Y. A study of work stress, patient handling activities and the risk of low back pain among nurses in Hong Kong. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36:794–804. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi SD, Brings K. Work-related musculoskeletal risks associated with nurses and nursing assistants handling overweight and obese patients: A literature review. Work. 2015;53:439–448. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Arcy LP, Sasai Y, Stearns SC. Do assistive devices, training, and workload affect injury incidence? Prevention efforts by nursing homes and back injuries among nursing assistants. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:836–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serranheira F, Sousa-Uva M, Sousa-Uva A. Hospital nurses’ tasks and work-related musculoskeletal disorders symptoms: A detailed analysis. Work. 2015;51:401–409. doi: 10.3233/WOR-141939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sezgin D, Esin MN. Predisposing factors for musculoskeletal symptoms in intensive care unit nurses. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:92–101. doi: 10.1111/inr.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carneiro P, Martins J, Torres M. Musculoskeletal disorder risk assessment in home care nurses. Work. 2015;51:657–665. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoe VC, Kelsall HL, Urquhart DM, Sim MR. Risk factors for musculoskeletal symptoms of the neck or shoulder alone or neck and shoulder among hospital nurses. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2012;69:198–204. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alamgir H, Yu S, Drebit S, et al. Are female healthcare workers at higher risk of occupational injury? Occup Med. 2009;59:149–152. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urbanetto Jde S, da Silva PC, Hoffmeister E, et al. Workplace stress in nursing workers from an emergency hospital: Job Stress Scale analysis. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2011;19:1122–1131. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692011000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiwaridzo M, Makotore V, Dambi JM, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among registered general nurses: a case of a large central hospital in Harare, Zimbabwe. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:315. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3412-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munabi IG, Buwembo W, Kitara DL, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders among nursing staff: a comparison of five hospitals in Uganda. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17:81. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.17.81.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freimann T, Coggon D, Merisalu E, et al. Risk factors for musculoskeletal pain amongst nurses in Estonia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:334. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darby B, Gallo AM, Fields W. Physical attributes of endoscopy nurses related to musculoskeletal problems. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2013;36:202–208. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e31829466eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Komurcu HF, Kilic S, Anlar O. Relationship of age, body mass index, wrist and waist circumferences to carpal tunnel syndrome severity. Neurol Med Chir. 2014;54:395–400. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa2013-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naidoo R, Coopoo Y. The health and fitness profiles of nurses in KwaZulu-Natal. Curationis. 2007;30:66–73. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v30i2.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smedley J, Inskip H, Trevelyan F, et al. Risk factors for incident neck and shoulder pain in hospital nurses. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:864–869. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.11.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Heuvel SG, Heinrich J, Jans MP, et al. The effect of physical activity in leisure time on neck and upper limb symptoms. Prev Med. 2005;41:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coury HJ, Moreira RF, Dias NB. Evaluation of the effectiveness of workplace exercise in controlling neck, shoulder and low back pain: a systematic review. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy. 2009;13:461–479. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreira RF, Foltran FA, Albuquerque-Sendín F, et al. Comparison of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials evidence regarding the effectiveness of workplace exercise on musculoskeletal pain control. Work. 2012;Suppl 1:4782–4789. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0764-4782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheikhzadeh A, Gore C, Zuckerman JD, Nordin M. Perioperating nurses and technicians' perceptions of ergonomic risk factors in the surgical environment. Appl Ergon. 2009;40:833–839. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charney W, Simmons B, Lary M, Metz S. Zero lift programs in small rural hospitals in Washington state: reducing back injuries among health care workers. AAOHN J. 2006;54:355–358. doi: 10.1177/216507990605400803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ovayolu O, Ovayolu N, Genc M, Col-Araz N. Frequency and severity of low back pain in nurses working in intensive care units and influential factors. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30:70–76. doi: 10.12669/pjms.301.3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arvidsson I, Gremark Simonsen J, Dahlqvist C, et al. Cross-sectional associations between occupational factors and musculoskeletal pain in women teachers, nurses and sonographers. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:35. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-0883-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reed LF, Battistutta D, Young J, Newman B. Prevalence and risk factors for foot and ankle musculoskeletal disorders experienced by nurses. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ellapen TJ, Narsigan S. Work related musculoskeletal disorders among nurses: systematic review. J Ergonomics. 2014;4:S4–003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choobineh A, Movahed M, Tabatabaie SH, Kumashiro M. Perceived demands and musculoskeletal disorders in operating room nurses of Shiraz city hospitals. Ind Health. 2010;48:74–84. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.48.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Negewo AF, Gudeta SY. Nurses Perception about Nurse Caring Behaviors in Hospitals of Harari Region, East Ethiopia. Journal of Nursing & Patient Care. 2018;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Porter CA, Cortese M, Vezina M, Fitzpatrick JJ. Nurse caring behaviors following implementation of a relationship centered care professional practice model. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2014;7:818–822. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sarafis P, Rousaki E, Tsounis A, et al. The impact of occupational stress on nurses' caring behaviors and their health related quality of life. BMC Nurs. 2016;15:56. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0178-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poirier P, Sossong A. Oncology patients' and nurses' perceptions of caring. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2010;20:62–65. doi: 10.5737/1181912x2026265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peacock‐Johnson A. Nurses' perception of caring using a relationship‐ based care model. J Compr Nurs Res Care. 2018;3:128. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li B, Bruyneel L, Sermeus W, et al. Group-level impact of work environment dimensions on burnout experiences among nurses: a multivariate multilevel probit model. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Taris TW, et al. A multigroup analysis of the job demands-resources model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management. 2003;10:16. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duffield C, Roche M, Merrick ET. Methods of measuring nursing workload in Australia. Collegian. 2006;13:16–22. doi: 10.1016/s1322-7696(08)60512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mrayyan MT. Jordanian nurses' job satisfaction, patients' satisfaction and quality of nursing care. Int Nurs Rev. 2006;53:224–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2006.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hidayati L, Rifai F, Ni'mah L. Emotional Intelligence and Caring Behavior Among Muslim Nurse: A Study in Religious-Based Hospital in Surabaya-Indonesia. Advances in Health Sciences Research. 2017;3:136–139. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rafii F, Hajinezhad ME, Haghani H. Nurse caring in Iran and its relationship with patient satisfaction. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;26:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Costa G, Sartori S. Ageing, working hours and work ability. Ergonomics. 2007;50:1914–1930. doi: 10.1080/00140130701676054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mohamed NA, Mohamed SA. Impact of job demand and control on nurses intention to leave obstetrics and gynecology department. Life Sci J. 2013;10:2239. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pillay R. Work satisfaction of professional nurses in South Africa: a comparative analysis of the public and private sectors. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]