Abstract

Objective

Advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma is a heterogeneous group with limited treatment options. TACE has been advocated recently by various study groups. The purpose of this study was to evaluate if TACE in combination with sorafenib, as well as TACE alone, was safe and efficacious in treating BCLC stage C HCC.

Methods

A retrospective evaluation of the clinical data of 78 patients with BCLC stage C HCC who received either TACE-sorafenib (TS) combination therapy or TACE monotherapy as their first treatment was done. The two groups were compared in terms of radiological tumor response 1 month after the intervention. The two groups were also compared in terms of time to progression (TTP), overall survival (OS), and adverse events.

Results

The disease control rate (44.9% and 25.8%, respectively, P = 0.09) was higher in the TS combination group than in the TACE monotherapy group after 1 month of treatment. The TS combination group had significantly superior TTP and OS than the TACE group (TTP was 4.6 and 3.1 months, respectively, P = 0.001), and OS was 10.1 and 7.8 months, respectively, P < 0.001). The TACE-S group had a greater cumulative survival time at 6 months, 9 months, and 1 year than the TACE group (97.9%, 51.1%, 25.7% vs. 90.4%, 51.6%, and 0%, respectively).

Conclusion

TS combination therapy in advanced-stage (BCLC-C) HCC significantly improved disease control rate, TTP, and OS compared with TACE alone, without any significant increase in adverse reactions.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), TACE, sorafenib, overall survival

Abbreviations: ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; BCLC, Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer; CT, Computed tomography; CTCAE, Common terminology criteria for adverse events; CTP, Child–Turcotte–Pugh; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Group; EHS, Extrahepatic spread; HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; m-RECIST, Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; MVI, Macrovascular invasion; OS, Overall survival; PS, Performance status; SPSS, Statistical Package for Social Sciences; TACE, Transarterial chemoembolisation; TS, TACE-sorafenib; TTP, Time to tumor progression

The most frequent primary liver tumor is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is also the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally.1 HCC in its initial stages is usually asymptomatic, and it can go misdiagnosed for a long time. More than 50% of all HCCs are detected at an intermediate or advanced tumor stage, which limits treatment options to palliative care and results in a poor prognosis.2 The Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system is currently the most widely used clinical staging approach.3,4 The Eastern Cooperative Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) 1 or 2, macrovascular invasion (MVI), and extrahepatic spread (EHS) are used to define advanced-stage HCC (Stage C) in BCLC staging.4 The group is diverse, with survival ranging from 3.1 to 38.6 months, depending on the rationale for stage assignment.5 Patients with advanced HCC frequently die of hepatic failure or intra-hepatic tumor progression rather than metastatic disease progression.6,7 Systemic chemotherapy is the standard of care in the advanced HCC group. Sorafenib is probably the most extensively used treatment for patients with advanced unresectable HCC, as recommended by different clinical practice guidelines based on evidence from randomized clinical trials such as SHARP, Asia Pacific Trial, and GIDEON.3,8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Sorafenib is a multikinase inhibitor that reduces tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis by directly inhibiting the Ras/Raf/MEKUERK signaling pathway.10,11 The benefit of sorafenib alone in terms of survival is minimal, and it varies depending on tolerability. Due to poor toleration and drug-related side effects, the drug dosage may need to be adjusted or terminated. This subset of patients is difficult to treat because sorafenib is not tolerated. TACE produces tumor necrosis and hypoxia, which enhances angiogenesis and is a primary cause of tumor recurrence or metastasis and may lead to poor outcomes. Hypoxia generated by TACE increases the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), which in turn increases the expression of VEGF and platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFRs). The tyrosine kinase receptors VEGFR-2/3 and PDGFR-b are both inhibited by sorafenib. TACE and sorafenib are expected to complement each other, reducing post-TACE VEGF and PDGF overexpression and hence enhancing TACE efficacy.13, 14, 15, 16 Multiple RCTs have explored into the role of TACE-sorafenib (TS) combination therapy in unresectable HCC. The TACTICS trial shown that the combination of TACE and sorafenib can improve clinical outcomes and may be a viable therapy option for patients with unresectable HCC without vascular invasion or EHS who are good TACE candidates.15 TS combination therapy has been studied in advanced HCC (BCLC stage C) and has shown to increase outcome and survival.16, 17, 18 Furthermore, several studies have shown that TACE alone is as effective as sorafenib in selected patients with advanced HCC who had major portal vein invasion or EHS.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25

We did a retrospective analysis of patients who underwent TACE with or without sorafenib for advanced-stage HCC to examine the safety and outcome of TACE alone or TS combination due to the limits of available therapeutic options for advanced-stage HCC.

Materials and methods

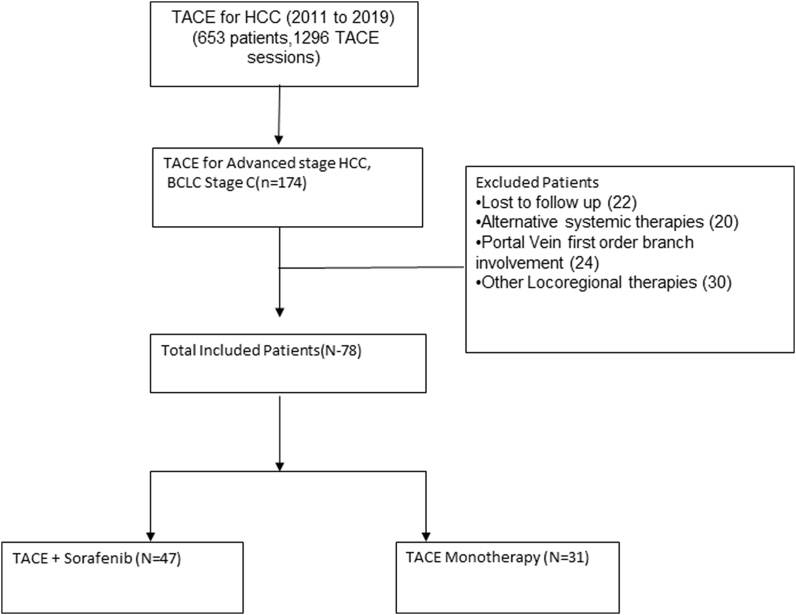

Institutional review board/Institutional Ethics Committee approval was taken for this retrospective analysis of all patients who underwent TACE for advanced-stage HCC between January 2011 and December 2019. The patients' and their relatives' informed consent was obtained before the procedure. The study's main goal was to compare overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced-stage HCC who were treated with either TS combination therapy or TACE monotherapy. The study's secondary goals were to assess the radiological response in terms of time to tumor progression (TTP) and complications after each therapy. We reviewed the hospital database system for patients with advanced-stage HCC who underwent TACE. TACE was used on a total of 653 individuals with HCC, with a total of 1296 TACE sessions. Out of these, 78 patients with radiologically confirmed advanced BCLC stage C (extrahepatic vascular invasion and/or metastases) were included in this study, omitting individuals who were not followed up on or had inadequate clinical details (Figure 1). TS combination therapy was given to 47 individuals (group A), whereas TACE monotherapy was given to 31 individuals (group B). TACE monotherapy was given to patients in group B when they developed dose-related, sorafenib-related side effects (mainly dermatologic, fatigue and weight loss, diarrhea, and worsening of liver function) within 2 weeks of commencing the medicine and alternative therapy was not an option due to various reasons (multidisciplinary team decision) (Figure 1). The tumors in all of the patients in the research were either biopsy-proven or had multiphasic imaging confirmation. The following were the inclusion criteria: serum bilirubin less than 3 mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) less than 5 times the upper limit of normal, Child–Pugh class A/B, HCC with MVI or EHS. On pre-procedural cross-sectional imaging, tumor thrombosis involving the main portal trunk or in both the left and right portal veins, major hepatic veins, inferior vena cava were characterized as an MVI (Figure 2). In our study, EHS included lung, nodes, abdominal/chest deposits, and bone metastases, and patients with limited EHS (extrahepatic disease burden not more than the primary disease, i.e., with only single metastasis) were included (Figure 3). Patients who underwent surgical resection, liver transplantation, radiofrequency ablation, or loco-regional treatments, refractory ascites, clinical encephalopathy, or any other contraindications to TACE were excluded. All the patients in this research had received at least one TACE session, with additional TACE sessions based on tolerance and treatment response. Sorafenib and TACE were given together in the combination therapy group. Patients were given oral sorafenib 400 mg twice daily for more than 1 month and until they died, with dose adjustments as needed based on side effects and tolerability.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the materials and methods.

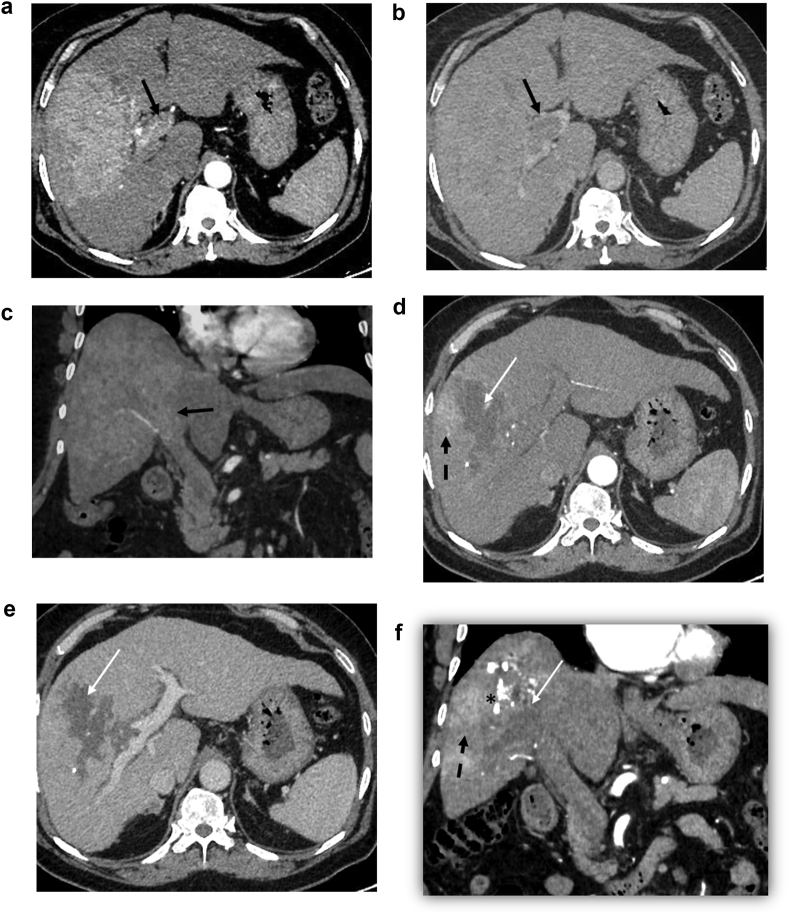

Figure 2.

A 64-year-old patient with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and portal vein tumoral thrombosis underwent conventional TACE. Preprocedure arterial phase axial (a) and coronal (c) phase images shows an arterial enhancing infiltrative HCC in the right lobe with tumoral thrombus involving the right and main portal veins (black arrow). Washout in the lesion as well as tumoral thrombus in the portal vein can be seen in the venous phase image (b). The 3-month follow-up CECT after lipiodol-TACE arterial phase (d, f) demonstrates PR in the form of tumor necrosis (white arrow), residual lipiodol deposit (asterisk), and residual arterial enhancement in the lesion (dashed black arrow). The venous phase (e) of the lesion reveals partial necrosis.

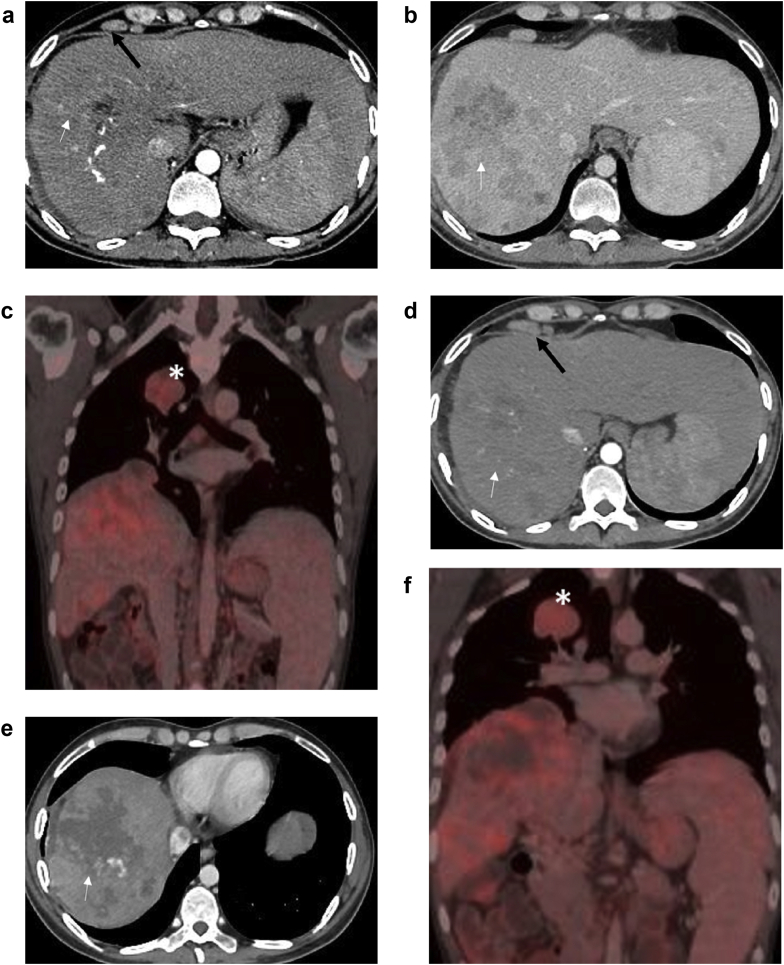

Figure 3.

A 35-year-old patient with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with metastasis underwent conventional TACE. Preprocedure multiphasic PET-CT shows an arterial enhancing infiltrative HCC in the right lobe in the arterial phase (a) with washout (white arrow) in the venous phase (b). Enlarged epiphrenic lymph nodes are also noted (black arrow in a). Coronal fusion PET-CT image (c) shows uptake in the hepatic lesion and in the lung metastasis in the right-upper lobe (Asterisk). The 3-month follow-up multiphasic PET-CT scan after lipiodol-TACE demonstrates PR in the form of tumor necrosis (white arrow) in arterial (d) and venous phase (e). The metastasis size (asterisk) is stable over this interval as seen on PET-CT fusion image (f).

TACE Procedure

The common femoral artery was accessed using a standard Seldinger technique. To examine arterial architecture and tumor vascularization, celiac and mesenteric arteriograms were performed. A micro-catheter (Progreat 2.7 Fr coaxial micro-catheter system, Somerset, NJ: Terumo Medical Corporation) was used to perform superselective cannulation of the segmental or sub-segmental hepatic artery branches feeding the tumor, which was then embolized either with epirubicin and lipiodol emulsion (Guerbet, Paris, France) or epirubicin-loaded drug-eluding beads (HepaSpheres, Meritmedical, USA). In case of extrahepatic blood supply to the tumor (the inferior phrenic, intercostal arteries or internal mammary, etc.), the respective arteries were cannulated and embolized in the same way. The endpoint of embolization was regarded to be blood flow stasis or near standstill (sluggish). Finally, gel foam was used to embolize the artery supplying the tumor in conventional TACE.

Follow-up

On days 2–5 after TACE, all the patients' serum bilirubin, AST, and ALT levels were monitored to assess the parenchymal injury and the risk of acute liver failure, as recommended by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0, for toxicities). OS was the major goal. An outpatient visit or a telephone interview served as the basis for the follow-up. Multiphasic contrast-enhanced CT/MRI was used to assess therapy response in both groups 1 month after TACE, followed by 2–3 month intervals in the first year and 6-month intervals afterward until the last follow-up or survival. The tumor response (intrahepatic and extrahepatic tumor) was graded as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease based on comparison with the baseline contrast-enhanced CT/MRI before first TACE, according to modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (m-RECIST) criteria. Further TACE sessions were decided on the basis of the response at 1-month follow-up imaging. Objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) were calculated. The percentage of individuals whose disease decreased (PR) or disappeared (CR) after the treatment was defined as the ORR. DCR included the percentage of patients whose disease was reduced (ORR) or was constant (SD) over time. TTP, OS, and complications/adverse effects were the main criteria assessed and compared in the two groups. The time from the initial TACE to objective radiographic tumor progression based on m-RECIST criteria was designated as the TTP. The time from the first TACE to death from any cause was referred to as OS. The results linked to ECOG -PS, Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP) score, MVI, and EHS are the other factors studied in these groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software (version 23). The student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test were used to analyze continuous data. Chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used to assess categorical parameters, which were presented as frequency and percentages. Kaplan–Meier curve was used for survival analysis, and comparison was performed by log-rank test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of Baseline Data

Table 1 summarizes and compares the baseline characteristics of the 78 patients. In both groups, men predominated, with viral etiology being the most common cause of cirrhosis leading to HCC. Age, gender, CTP score, preoperative alpha-fetoprotein, bilirubin, albumin, ECOG-PS, tumor size, number of tumors, MVI, and EHS showed no significant difference between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Only MVI was seen in the majority of patients (42/78, 53.84%), followed by EHS without vascular invasion (27/78, 34.6%). The most prevalent sites of metastases were extrahepatic metastases to the lung and nodes, accounting for 54.28% and 37.14% of all metastases, respectively. Both MVI and EHS were observed in 11.5% (9/78) of the participants.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristic Comparison of the Two Groups.

| TACE + sorafenib (TS) | TACE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) (Years) | 57.47 ± 8.89 | 60.71 ± 11.01 | 0.158 |

| Sex (male/female) | 40/7 | 29/2 | 0.296 |

| Cause of HCC | 0.884 | ||

| Hepatitis B | 18 | 11 | |

| Hepatitis C | 7 | 7 | |

| NASH | 10 | 7 | |

| Ethanol | 9 | 5 | |

| Cryptogenic | 3 | 1 | |

| Tumor size (cm) (mean ± SD) | 7.91 ± 3.07 | 8.30 ± 3.31 | 0.586 |

| Tumor number (single/multiple) | 19/28 | 14/17 | 0.667 |

| ECOG-PS | 0.276 | ||

| 0 | 19 | 9 | |

| 1 | 26 | 22 | |

| 2 | 2 | – | |

| AFP value | 0.431 | ||

| <400 ng/L/>400 ng/L | 20/27 | 15/16 | |

| CTP score | 0.476 | ||

| A | 31 | 18 | |

| B | 16 | 13 | |

| Total serum bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.36 | 1.49 | 0.332 |

| Total serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.20 | 3.06 | 0.258 |

| MVI only | 22 | 20 | 0.179 |

| EHS only | 19 | 8 | 0.134 |

| Both | 6 | 3 | 0. |

| Number of TACE sessions (≤2/>2) | 29/18 | 23/8 | 0.254 |

| Duration of sorafenib (months) | 5.5 ± 2.3 | NA |

TACE, trans arterial chemoembolization; SD, standard deviation; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; CTP, Child–Turcotte–Pugh; MVI, macrovascular invasion; EHS, extrahepatic spread.

Treatment, Response, and Survival

Patients in the TS combination therapy group received comparable TACE sessions to the TACE monotherapy group (Table 1). In the combination therapy group, sorafenib was administered for an average of 5.5 ± 2.3 months. SD was the best radiological response based on m-RECIST criteria in 36 (46.15%) of the patients at 1 month, followed by PR in 27 (34.62%). Only two patients in the combination group showed CR. Patients with progressive disease accounted for 13 (16.67%) of the total. At 1 month, the two groups' response assessments were comparable (Table 2). The TS combination group had a higher DCR than the TACE monotherapy group (P = 0.04). The overall response rate was likewise higher in the combination group, although there was no statistically significant difference.

Table 2.

Summary of Tumor Response at 1-month Follow-up Scan; n (%).

| CR | PR | SD | PD | ORR | DCR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TACE + sorafenib | 2(4.2%) | 19(40.4%) | 21(44.7%) | 5(10.6%) | 21(44.9%) | 43(91.5%) |

| TACE | 0(0%) | 8(25.8%) | 15(48.4%) | 8(25.8%) | 8(25.8%) | 23(74.1%) |

| P-value | 0.09 | 0.04a |

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Significant p-value

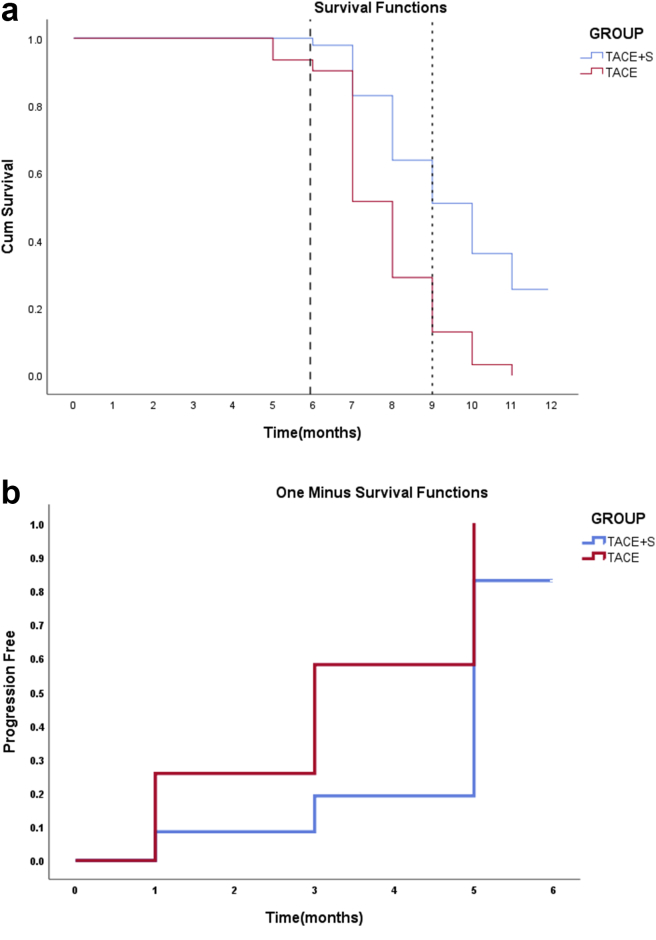

Our study population's mean TTP was 4.05 ± 1.9 months (median: 5 months, IQR: 3–5months). The mean OS was 9.22 ± 2.6 months (median: 8.5 months, IQR: 7–10 months). Half-yearly, 9-month, and 1-year survival rates of patients in the TACE group were 90.4%, 51.6%, and 0%, respectively; the survival rates of patients in the combined group were 97.9%, 51.1%, and 25.7%. TTP and OS differed significantly between the two groups, with combination therapy having a greater OS and longer TTP than TACE monotherapy (Table 3) (Figure 4a and b). CTP score A and PS 0–1 had improved OS in both groups compared with CTP score B and PS 2, although the difference was not significant. Patients who had both extrahepatic vascular invasion and metastases had a lower OS rate (7.44 months) than patients who had both MVI (9.74 months) and metastasis (9 months). OS was compared among the groups, and TS combination showed significant difference for MVI and EHS (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of TTP and OS Between the Two Groups.

| TTP (months) | OS (months) | |

|---|---|---|

| TACE + sorafenib | 4.62 ± 1.89 | 10.15 ± 2.8 |

| TACE | 3.19 ± 1.57 | 7.81 ± 1.4 |

| P-value | 0.001∗∗ | <0.001a |

TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TTP, time to progression; OS, overall survival.

Significant p-value

Figure 4.

(a) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for comparison of overall survival between TACE + sorafenib (TS) group and TACE group (P < 0.001). (b) Kaplan–Meier curve for comparison of TTP between TS group and TACE group (P = 0.001).

Table 4.

Subgroup Analysis of OS Between MVI and EHS.

| MVI | EHS | MVI + EHS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TACE-sorafenib | 11.44 ± 2.67 | 9.42 ± 2.67 | 6, 7.83 ± 1.16 |

| TACE | 7.90 ± 1.55 | 8 ± 0.75 | 3, 6.67 ± 1.52 |

| P-value | <0.001a | 0.04a | 0.321 |

Significant P-value, TACE-trans arterial chemoembolization, MVI, macrovascular invasion; EHS, extrahepatic spread; OS, overall survival.

Complications and Safety

Post-embolization syndrome was the most common TACE consequence in both groups (60% in the combination therapy group and 55% in the TACE monotherapy group), with symptoms including fever, upper abdomen pain/discomfort, nausea, and lack of appetite. Following TACE, this syndrome was self-limiting and was managed with supportive care. Transient hepatic dysfunction was diagnosed by abnormal liver function tests and a slight increase in the amount of the ascites/new-onset ascites in about 11% of the patients in both groups. During the postprocedural hospital stay, the hepatic dysfunction caused by TACE also improved over a week and reverted to the baseline levels. In our study, the most common side effect related to sorafenib was hand–foot skin responses (54%, 20/37) followed by diarrhea (29.7%,11/37). Appropriate dose adjustments were carried out on outpatient department basis. Aside from the modest problems stated above, neither group experienced any serious side effects.

Discussion

The overall efficacies of TS combination and TACE monotherapy in patients with BCLC stage C HCC were investigated in this study. Several recent investigations have discovered that performing local TACE improves survival in this population.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 In this retrospective cohort analysis, we discovered that concurrent treatment with sorafenib and TACE may prolong TTP and OS in patients with advanced HCC compared with TACE monotherapy. A Kaplan–Meier curve was used to demonstrate the effect of sorafenib plus TACE in extending OS and TTP in patients with HCC involving the portal vein or extrahepatic metastasis.

As a widely used molecular targeted medication, sorafenib has shown tremendous promise in the treatment of advanced HCC.10, 11, 12 Significant number of newer anti-angiogenic (VEGFR pathway inhibitors) agents beyond sorafenib have shown efficacy in the treatment of advanced HCC and includes lenvatinib, regorafenib, cabozantinib, and ramucirimab. In addition, a new class of immune checkpoint inhibitors is available, which acts either through interruption of the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 or between CTLA-4 and B7 and includes nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and tremelimumab.1

Patients with advanced HCC who have MVI or EHS have a poor prognosis, and local therapeutic options such as TACE are not listed in several clinical practice guidelines.3,8,9 In advanced HCC, sorafenib is the most commonly prescribed treatment. Patients who received sorafenib over placebo had a survival advantage of 10.7 months compared with 7.9 months in the SHARP trial.10 Compared with placebo or other modalities, average survival was shown to be in the range of 5–10.7.10, 11, 12,27,28

TACE coupled with sorafenib has been advocated in prior comparative studies for advanced-stage HCC, with significant survival improvements over sorafenib alone.25,28, 29, 30, 31, 32 The TS combination group had a greater DCR than the TACE monotherapy group in our trial, but there was no statistically significant difference in total response rate. This could indicate that, despite the lack of a partial or CR, the combination therapy was able to slow the progression of the disease. In our study, the TS combination group's OS was 10.1 + 2.8 months, which was superior to that of the TACE monotherapy group (7.81 + 1.4 months). In addition, there was a substantial difference in time to progression, with combination therapy delaying TTP. OS has been found in previous studies to last anywhere from 7 to 27 months (Table 5). In our investigation, the combined group's OS was higher than Hu et al but was lower than the other studies32 (Table 5). The difference might be attributed to some reasons including the number of TACE sessions used, sorafenib duration, and difference in patient selection. In our patient selection criteria, we did not include patients with second- and third-order portal vein invasion, which might be the reason for decreased OS in our study compared with other abovementioned studies.

Table 5.

Comparison With Previous Studies.

| Type of study | Type of subjects | Number of subjects (TS/T/S) | TACE + sorafenib (TS) | TACE monotherapy (T) | Sorafenib (S) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koch et al28 | Retrospective TS/T/S |

BCLC stage C | 54/65/82 | 16.5 months [95%CI:15.0–18.1] |

10.5 months [95%CI:7.5–13.6] |

8.4 months [95%CI:6.0–10.8] |

| Ren et al29,a,b | Retrospective (propensity score matched) |

Unresectable HCC | 31/50 (1:2 matching) |

15.8 ± 2 months (95%CI:11.82–19.78) |

8.3 ± 1.4 months (95%CI:5.52–11.07) |

NA |

| Qu et al30,a,b | Retrospective TS/T |

Unresectable HCC | 29/18/0 | 27 months [95%CI:19.07–35.32] |

12 months [95%CI:9.96–16.02] |

NA |

| Liu et al31,b | Retrospective | BCLC stage C | 35/40 | 13.6 months | 6.3 months | NA |

| Hu et al32,b | Retrospective (propensity score matched) |

BCLC stage C | 82/164 (1:2 matching) |

7 months | 4.9 months | NA |

| Bettinger et al25 | Retrospective TS/T/S |

Metastatic HCC | 23/42/48 | 16 months [95%CI:9.94–22.10] | 9 months [95%CI:4.46–13.54] |

6 months [95%CI:4.67–7.33] |

| Our studyb | Retrospective | BCLC stage C | 47/31 | 10.15 ± 2.8 months | 7.81 ± 1.4 months | NA |

- Results from subgroup analysis.

Study comparing TACE + sorafenib (TS) and TACE (T) monotherapy only, TACE, trans arterial chemoembolisation; BCLC, Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CI, confidence interval.

Patients who were unable to tolerate sorafenib were given TACE, which resulted in a mean survival of 7.81 + 1.4 months in our trial. TACE monotherapy findings were comparable with those of other studies, with OS ranging from 4.9 to 12 months (Table 4). Zhao et al conducted a retrospective comprehensive evaluation comparing TACE monotherapy to sorafenib and found that the TACE monotherapy group had a median survival of 14 months, and the sorafenib group had a median survival of 9.7 months.26 Few additional retrospective trials comparing TACE, sorafenib, and TS monotherapies have found similar results, with TACE providing a survival benefit compared with sorafenib.25,28, 29, 30, 31, 32 TACE can, thus, be used in a group of patients who cannot tolerate sorafenib with equivalent survival advantages.

Multiple recent studies have indicated that adding TACE to patients with advanced HCC owing to portal venous invasion improves survival.20, 21, 22 In our subset of patients with MVI, the TACE-S group and TACE monotherapy had OS of 11.4, and 7.9 months, respectively (Table 4). Those who underwent TACE had a significantly superior 1-year survival rate than patients in the control group (P = 0.03) in a meta-analysis by Leng et al comparing prospective trials.20 Patients with advanced HCC with portal vein invasion who underwent TACE had a higher OS rate, according to another study by Liu et al. Patients with right/left and segmental branch involvement had a better outcome than those with main portal vein involvement in the same study.22 TACE-S exhibited better outcomes for the first- and lower-order portal vein thrombosis than in the main portal vein, according to a meta-analysis by Zhang et al33. Comparing TACE monotherapy with TS, this meta-analysis indicated that TS improves 6-month and 1-year OS.

In our subset of patients with extrahepatic metastases, the TS combination group and TACE monotherapy had OS of 9.42, and 8 months, respectively (Table 4). Because intrahepatic HCC progression determines the prognosis of patients with metastatic HCC, local therapy with TACE may enhance OS. Few studies have shown that slowing intrahepatic HCC progression with TACE improves survival in advanced illness compared with systemic treatment.23, 24, 25 Compared with TACE alone (9 months) or sorafenib monotherapy (6 months), Bettinger et al found a substantial (p-0.002) survival benefit in a group of patients with advanced HCC with EHS treated with combination therapy (16 months).25 In a study by Yoo et al, the median survival time of patients classified as Child–Pugh A and T3-stage HCC and treated with TACE-S combination therapy, TACE monotherapy, and conservative management was 10, 5, and 2.9 months, respectively, with a significant difference among the groups. The median survival was 7.1, 2.6, and 1.6 months in patients classified as Child–Pugh B and T3-stage, respectively.24 TACE also showed efficacy in a few studies and case reports where pulmonary metastases of HCC were controlled and even regressed, extending the life span of advanced HCC patients; however, the mechanism of this process remains unknown.23

Patients with advanced HCC are a diverse group, with varying degrees of underlying hepatic illness and treatment response. As a result, lumping them all together and denying them strong treatment alternatives like TACE may not be the best idea. There is a good chance that a subgroup of patients with this advanced disease will benefit from the addition of TACE to sorafenib.

TACE is also an option for patients who are unable to tolerate, afford, or obtain systemic monotherapy, as it provides better, albeit not superior, OS.

Because of the side effects related to sorafenib, patients' survival may be affected if their dose is reduced or discontinued. Even in our trial, 31 patients who were given TACE monotherapy were unable to tolerate sorafenib or had difficulty with compliance; in these circumstances, TACE monotherapy is an acceptable replacement. Conservative embolization and optimal patient selection can reduce the risk of hepatic decompensation following TACE in individuals with portal vein invasion. In our research, no serious complications were found in either group. In both groups, a poor CTP score and the presence of both extrahepatic vascular invasion and metastases were linked to a poor outcome and survival.

The retrospective character of the study, as well as the related selection bias, and the relatively small sample size, are the limitations of our study. It was difficult to control many factors like time of starting sorafenib with respect to TACE, number of sessions of TACE used in all cases, dose of sorafenib used and tolerated. Sorafenib monotherapy group was not added for comparison, which is another limitation. Furthermore, our study population was small in number, and subgroup analysis of EHS and MVI was not possible. To validate the use of combination therapy in advanced HCC, a large prospective randomized controlled trial is needed. Furthermore, as newer drugs become available, future studies will provide an insight into the effects of combining trans arterial therapy with these newer drugs.

Based on our findings, we conclude that TACE monotherapy or TS combination therapy is an acceptable and safe alternative to sorafenib monotherapy in the management of select patients with advanced HCC, providing improved outcome and a definite survival benefit, particularly in patients with CTP-A and those who cannot tolerate sorafenib. Even though the combination therapies are not mentioned as a preferred mode of treatment in guidelines and treatment algorithms, we have irrefutable evidence from several studies and our own experience that combination therapy and individualized therapy is the way forward in the management of advanced HCC.

Credit authorship contribution statement

PY, CK, CN, MA, SKS—Conceptualized the study design; PY, CK, CN, SVS—Collected the data, analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Jindal A., Thadi A., Shailubhai K. Hepatocellular carcinoma: etiology and current and future drugs. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019 Mar-Apr;9:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.01.004. Epub 2019 Jan 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinter M., Hucke F., Graziadei I., Vogel W., Maieron A., Königsberg R., et al. Advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: transarterial chemoembolization versus sorafenib. Radiology. 2012;263:590–599. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018 Jul;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. Epub 2018 Apr 5. Erratum in: J Hepatol. 2019 Apr;70(4):817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tellapuri S., Sutphin P.D., Beg M.S., Singal A.G., Kalva S.P. Staging systems of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2018 Nov;37:481–491. doi: 10.1007/s12664-018-0915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giannini E.G., Bucci L., Garuti F., et al. Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma need a personalized management: a lesson from clinical practice. Hepatology. 2018 May;67:1784–1796. doi: 10.1002/hep.29668. Epub 2018 Apr 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okusaka T., Okada S., Ishii H., et al. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with extrahepatic metastases. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 1997;44:251–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uka K., Aikata H., Takaki S., et al. Clinical features and prognosis of patients with extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:414–420. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heimbach J.K., Kulik L.M., Finn R.S., et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018 Jan;67:358–380. doi: 10.1002/hep.29086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A., Acharya S.K., Singh S.P., et al. INASL task-force on hepatocellular carcinoma. 2019 update of Indian national association for study of the liver consensus on prevention, diagnosis, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma in India: the puri II recommendations. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020 Jan-Feb;10:43–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llovet J.M., Ricci S., Mazzaferro V., et al. SHARP investigators study group: sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng A.L., Kang Y.K., Chen Z., et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lencioni R., Kudo M., Ye S.L., et al. GIDEON (Global Investigation of therapeutic DEcisions in hepatocellular carcinoma and of its treatment with sorafeNib): second interim analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2014 May;68:609–617. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X., Feng G.S., Zheng C.S., Zhuo C.K., Liu X. Expression of plasma vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and effect of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization therapy on plasma vascular endothelial growth factor level. World J Gastroenterol. 2004 Oct 1;10:2878–2882. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i19.2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang B., Xu H., Gao Z.Q., Ning H.F., Sun Y.Q., Cao G.W. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Acta Radiol. 2008 Jun;49:523–529. doi: 10.1080/02841850801958890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kudo M., Ueshima K., Ikeda M., et al. TACTICS study group. Randomised, multicentre prospective trial of transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) plus sorafenib as compared with TACE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: TACTICS trial. Gut. 2020 Aug;69:1492–1501. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-3181934. Epub 2019 Dec 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bai W., Wang Y.J., Zhao Y., et al. Sorafenib in combination with transarterial chemoembolization improves the survival of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score matching study. J Dig Dis. 2013 Apr;14:181–190. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y., Wang W.J., Guan S., et al. Sorafenib combined with transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a large-scale multicenter study of 222 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013 Jul;24:1786–1792. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt072. Epub 2013 Mar 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng Z., He L., Guo Y., Song Y., Song S., Zhang L. The combination therapy of transarterial chemoembolisation and sorafenib is the preferred palliative treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2020 Sep 11;18:243. doi: 10.1186/s12957-020-02017-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xue T.C., Xie X.Y., Zhang L., Yin X., Zhang B.H., Ren Z.G. Transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: a meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013 Apr 8;13:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leng J.J., Xu Y.Z., Dong J.H. Efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis: a meta-analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2016 Oct;86:816–820. doi: 10.1111/ans.12803. Epub 2014 Aug 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerrito L., Annicchiarico B.E., Iezzi R., Gasbarrini A., Pompili M., Ponziani F.R. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with portal vein tumor thrombosis: beyond the known frontiers. World J Gastroenterol. 2019 Aug 21;25:4360–4382. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i31.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Lei, Zhang Cheng, Zhao Yan, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis: prognostic factors in a single-center study of 188 patients. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:8. doi: 10.1155/2014/194278. Article ID 194278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Huiyong, Zhao Wei, Liu Shuguang, et al. Pure transcatheter arterial chemoembolization therapy for intrahepatic tumors causes a shrink in pulmonary metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:1035–1042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoo D.J., Kim K.M., Jin Y.J. Clinical outcome of 251 patients with extrahepatic metastasis at initial diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: does transarterial chemoembolization improve survival in these patients? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Jan;26:145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bettinger D., Spode R., Glaser N., Buettner N., Boettler T., Neumann-Haefelin C., et al. Survival benefit of transarterial chemoembolization in patients with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma: a single center experience. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017 Aug 10;17:98. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0656-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Y., Cai G., Zhou L., et al. Transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma with vascular invasion or extrahepatic metastasis: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2013 Dec;9:357–364. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12081. Epub 2013 May 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chien S.C., Chen C.Y., Cheng P.N., et al. Combined transarterial embolization/chemoembolization-based locoregional treatment with sorafenib prolongs the survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and preserved liver function: a propensity score matching study. Liver Cancer. 2019 May;8:186–202. doi: 10.1159/000489790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch C., Göller M., Schott E., et al. Combination of sorafenib and transarterial chemoembolization in selected patients with advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study at three German liver centers. Cancers (Basel) 2021 Apr 28;13:2121. doi: 10.3390/cancers13092121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren B., Wang W., Shen J., Li W., Ni C., Zhu X. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) combined with sorafenib versus TACE alone for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score matching study. J Cancer. 2019 Jan 29;10:1189–1196. doi: 10.7150/jca.28994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qu X.D., Chen C.S., Wang J.H., et al. The efficacy of TACE combined sorafenib in advanced stages hepatocellullar carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2012 Jun 21;12:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu K.C., Hao Y.H., Lv W.F., et al. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with sorafenib in patients with BCLC stage C hepatocellular carcinoma. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2020 Aug 25;14:3461–3468. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S248850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu H., Duan Z., Long X., et al. Sorafenib combined with transarterial chemoembolization versus transarterial chemoembolization alone for advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a propensity score matching study. PLoS One. 2014 May 9;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X., Wang K., Wang M., et al. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) combined with sorafenib versus TACE for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017 Apr 25;8:29416–29427. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]