Abstract

Background

Mother‐infant proximity and interactions after birth and during the early postpartum period are important for breast‐milk production and breastfeeding success. Rooming‐in and separate care are both traditional practices. Rooming‐in involves keeping the mother and the baby together in the same room after birth for the duration of hospitalisation, whereas separate care is keeping the baby in the hospital nursery and the baby is either brought to the mother for breastfeeding or she walks to the nursery.

Objectives

To assess the effect of mother‐infant rooming‐in versus separation on the duration of breastfeeding (exclusive and total duration of breastfeeding).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (30 May 2016) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effect of mother‐infant rooming‐in versus separate care after hospital birth or at home on the duration of breastfeeding, proportion of breastfeeding at six months and adverse neonatal and maternal outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the studies for inclusion and assessed trial quality. Two review authors extracted data. Data were checked for accuracy. We assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included one trial (involving 176 women) in this review. This trial included four groups with a factorial design. The factorial design took into account two factors, i.e. infant location in relation to the mother and the type of infant apparel. We combined three of the groups as the intervention (rooming‐in) group and the fourth group acted as the control (separate care) and we analysed the results as a single pair‐wise comparison.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome, duration of any breastfeeding, was reported by authors as median values because the distribution was found to be skewed. They reported the overall median duration of any breastfeeding to be four months, with no difference found between groups. Duration of exclusive breastfeeding and the proportion of infants being exclusively breastfed at six months of age was not reported in the trial. There was no difference found between the two groups in the proportion of infants receiving any breastfeeding at six months of age (risk ratio (RR) 0.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.51 to 1.39; one trial; 137 women; low‐quality evidence).

Secondary outcomes

The mean frequency of breastfeeds per day on day four postpartum for the rooming‐in group was 8.3 (standard deviation (SD) 2.2), slightly higher than the separate care group, i.e. seven times per day. However, between‐group comparison of this outcome was not appropriate since every infant in the separate care group was breastfed at a fixed schedule of seven times per day (SD = 0) resulting in no estimable comparison. The rate of exclusive breastfeeding on day four postpartum before discharge from hospital was significantly higher in the rooming‐in group 86% (99 of 115) compared with separate care group, 45% (17 of 38), (RR 1.92; 95% CI 1.34 to 2.76; one trial, 153 women; low‐quality evidence). None of our other pre‐specified secondary outcomes were reported.

Authors' conclusions

We found little evidence to support or refute the practice of rooming‐in versus mother‐infant separation. Further well‐designed RCTs to investigate full mother‐infant rooming‐in versus partial rooming‐in or separate care including all important outcomes are needed.

Plain language summary

Rooming‐in for new mother and infant versus separate care for increasing duration of breastfeeding

What is the issue?

Keeping mother and infant together (rooming‐in) or separating them after birth are both traditional practices seen in many cultures. During the early 20th century when hospitals became the centre for birthing in industrialised countries, the practice of separate care became established. Newborns were placed in a nursery separated from their mothers and brought to their mother only for breastfeeding. The practice of mother‐infant rooming‐in became less practised. Mother‐infant proximity during the early postpartum period might directly influence mother‐infant interaction, which might impact on the duration of breastfeeding.

Why is this important?

Separating infants from their mothers after birth may reduce the frequency of breastfeeding and hence the amount of breast milk a mother produces. Whereas, infants staying together with the mother throughout their hospital stay would have more frequent suckling of the breast and thus promote closeness and bonding. Separate care might allow the mother to rest and reduce stress, which also might improve milk production. Many hospitals have now started to keep the mother and baby in the same room, particularly since the advent of the WHO/UNICEF Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative in 1991. This systematic review aimed to establish from randomised controlled trials whether rooming‐in or separate care after birth resulted in a longer duration of exclusive breastfeeding once they had returned home.

What evidence did we find?

The latest search was done on 30th May 2016. No new studies were identified. Only one study is included in the review.

One trial (involving 176 women) was analysed which provided information on the rate of exclusive breastfeeding on discharge from hospital. We found that there was low‐quality evidence that keeping mother and infant together in the same room after birth until they are discharged from the hospital increased the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at four days after birth. There was no difference between the groups in the proportion of infants receiving any breastfeeding at six months of age.

What does this mean?

We found little evidence to support or refute the practice of rooming‐in after birth. A randomised controlled trial is needed and it should report all important outcomes, including breastfeeding duration.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Comparison between rooming‐in versus separate care for new mother and infant for increasing the duration of breastfeeding.

| Comparison between rooming‐in versus separate care for new mother and infant for increasing the duration of breastfeeding | ||||||

|

Patient or population: 176 healthy mother‐infant dyads after normal spontaneous vaginal delivery (rooming‐in: 132, separate care: 44) Settings: 1 maternity home in St Petersburg, Russia Intervention: rooming‐in Comparison: separate care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Comparison between rooming‐in versus separate care | |||||

| Duration of any breastfeeding | This outcome was reported as a median and could not be included in any analysis. | |||||

| Proportion of women exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months | The trial included in the review did not report this outcome. | |||||

| Proportion of women with any breastfeeding at 6 months (nearly exclusive breastfeeding) | Study population | RR 0.84 (0.51 to 1.39) | 137 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Althought there was no blinding of the intervention and blinding of the outcome assessor is unclear, we did not downgrade for lack of blinding because we judged this to be an objective outcome not affected by blinding | |

| 406 per 1000 | 341 per 1000 (207 to 565) | |||||

| Frequency of breastfeeding per day | The mean frequency of breastfeeds per day on day 4 postpartum for the rooming‐in group was 8.3 (standard deviation (SD) 2.2), slightly higher than the separate care group, i.e. 7 times per day. However, analysis of this outcome was not possible since every infant in the separate care group was breastfed at a fixed schedule of 7 times per day (SD = 0) resulting in no estimable comparison. | |||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding at day 4 postpartum | Study population | RR 1.92 (1.34 to 2.76) | 153 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Although there was no blinding of the intervention and blinding of the outcome assessor is unclear, we did not downgrade for lack of blinding because we judged this to be an objective outcome not affected by blinding | |

| 447 per 1000 | 859 per 1000 (599 to 1000) | |||||

| Maternal level of confidence in breastfeeding | The trial included in the review did not report this outcome. | |||||

| Neonatal infection | The trial included in the review did not report this outcome. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level for risk of bias concerns due to differences in care between the groups other than the intervention and differences in the reason for attrition 2 Downgraded one level because estimate based on one small trial

Background

Description of the condition

Keeping a mother and her baby together in the same room or separating them after birth are both traditional practices. However, in the early part of 20th century, when hospitals became the predominant sites for birth in industrialised countries, separation of mothers and babies became widely practised. Newborns were cared for in hospital nurseries and mothers in postnatal wards. Babies were brought to their mothers for feeding, but otherwise remained in the hospital nursery until discharge. More recently some hospitals have begun the practise of keeping the mother and infant together in the same room to promote breastfeeding. Mother‐infant proximity during the early postpartum period may influence mother‐infant behaviour that is essential in regulation of breast‐milk production and milk supply and hence it might make a difference to whether a mother successfully breastfeeds (Bramson 2010; Bigelow 2014; Moore 2012).

Description of the intervention

Keeping mother and infant together has been termed rooming‐in. It is defined by World Health Organization (WHO 1998), as the hospital practice where postnatal mothers with normal infants (including those born by caesarean section) stay together in the same room 24 hours a day, from the time they arrive in their room after delivery. They remain together until discharge unless there is a specific medical indication which warrants separation. During rooming‐in the infant is placed close to the mother either by bed‐sharing, an attached side‐car crib or by her bedside in a stand‐alone cot.

Separating the infant from the mother in the hospital nursery after birth allows the mother to sleep and rest. While she is recuperating, she can either walk to the nursery whenever she feels ready, as frequently as she wishes or she can request the infant to be brought to her room for demand breastfeeding. Alternatively, all babies are brought from the nursery to their mothers at fixed intervals usually of about three or four hours (Hiller 2006). In order to maintain optimal breast‐milk production, the mother may continue to stimulate her breasts in between breastfeeds by either milking the breasts by hand massage or using the mechanical pump to emulate the infant's suckling (Hill 1996). Separate care may also be partial, for example it could be practised during the night with rooming‐in during the day or rooming‐in during the hospitalisation and separate care at home after discharge or vice versa.

How the intervention might work

Placing the infant in close proximity to the mother enables the mother to respond in a timely way whenever her infant shows signs of readiness to feed. Uninhibited mother‐infant interaction and close contact promotes bonding, encourages demand breastfeeding and results in more efficient infant suckling, all essential in the regulation of breast‐milk secretion (Bigelow 2014). Observational studies suggest that rooming‐in is associated with higher a breastfeeding frequency (Yamauchi 1990), a higher rate of exclusive breastfeeding (Buranasin 1991) and a longer duration of breastfeeding (Wright 1996). Furthermore, mothers who remain together with their infants reported more self‐confidence and felt more competent in caring for their infants (O'Connor 1980), and were more likely to continue to breastfeed their infants longer than those mothers who had their infants separated. Apart from the positive effects on breastfeeding, rooming‐in mothers may have a lower incidence of breast engorgement and milk stasis (Wilde 1999) due to frequent breast‐suckling by the infant and better infant weight gain due to less energy consumption from crying during early infancy (Yamauchi 1990). Rooming‐in may also be advantageous to infant's health as it is associated with lower incidence of neonatal diarrhoea (Mustajab 1986) and significant hyperbilirubinaemia (Suradi 1998) when compared to the infants in nursery care.

On the other hand, separate care might be harmful because the process of breast‐milk production begins immediately after parturition with secretion of copious breast milk in the first 24 to 36 hours, progressing to mature breast milk by 72 hours postpartum (Neville 2001). The regulation of breast‐milk production during this period is controlled by multiple factors including the maternal physical and psychological condition, the frequency of breastfeeding and effective infant suckling (Knight 1998; Neville 1988). Previous research has demonstrated that higher breastfeeding frequency during the early days of the puerperium contributes to optimal milk production (Daly 1993), higher milk volume (Wilde 1995), and an adequate milk supply for a longer period (Hill 2005) and thus, likely to result in an increase in the duration of breastfeeding. On the contrary, lack or delay in breast stimulation in the first few days after delivery may result in sub‐optimal breast‐milk production, low milk supply and early cessation of breastfeeding (Bigelow 2012; Neville 1988 ). In addition, breast milk expression when compared to direct breastfeeding is associated with a higher risk of mastitis (Potter 2005). One study suggested that mother‐infant separation in the early days of puerperium negatively affects the breast‐milk production and reduces the duration of breastfeeding (Elander 1984), but there are other studies that show maternal intention and interest in breastfeeding is the most important determining factor that influences the success of breastfeeding (Bergman 2013; Forster 2006; Lee 2007).

There is a perceived security concern for infants when other patients and visitors have access to them, especially in hospitals with open maternity wards. In the hospital nursery, there is tighter security as access to the infants is strictly limited to mothers and midwives and in some hospitals even mothers are not allowed into the nursery. One of the reasons for the practice of separate care was the belief that it would protect babies from infection. However, serious outbreaks of nursery infection were reported leading to a proposal that keeping the mother and baby together might prevent infections (Hiller 2006).

Labour is a stressful event for both the mother and infant. Most mothers, especially primigravidas and mothers who have had caesarean birth or prolonged and complicated labour, require adequate rest after childbirth in order to recover physically and psychologically. Increased levels of stress hormones during childbirth have been shown to affect the onset of breast‐milk production leading to early breastfeeding failure (Chen 1998), and this could be potentially reduced by separate care.

Why it is important to do this review

The duration of exclusive breastfeeding globally remains low, with only an estimated 35% of infants being exclusively breastfed up to four months of age (WHO 2012), despite the benefits of breastfeeding for six months being well‐established (Kramer 2012; Victora 1987). Among the factors in the early puerperium that contribute to failure to sustain lactation for a longer duration include the mother's condition after labour, psychological stress (Chen 1998), mode of delivery (Suradi 1998), individual cultural practice (Ingram 2003) and, most importantly, the maternal desire to breastfeed her infant.

Mother‐infant rooming‐in is recommended by WHO/UNICEF Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative 1991 in the 10 steps to successful breastfeeding. It is believed to be the most favourable arrangement for optimal breast‐milk production (WHO 1998). Although both separate care and rooming‐in are traditional practices, the benefits and harms have not been fully evaluated. Therefore, the aim of this review is to assess the effects of the practice of routine mother‐infant rooming‐in compared with the practice of routine separation of mothers and babies on the duration of breastfeeding.

Objectives

To assess the effect of mother‐infant rooming‐in versus separation on the duration of breastfeeding (exclusive and total duration of breastfeeding).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials including cluster‐randomised trials were eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

All mothers who have given birth and are able to care for their normal newborn infants whether or not they have initiated breastfeeding. Trials recruiting populations with specific health problems such as AIDS were not included in this review.

Types of interventions

For this update we have reversed the intervention and the comparison. We have taken rooming‐in as our intervention and separate care as the comparison (seeDifferences between protocol and review). Since both rooming‐in and separate care are traditional practices we have made this change because we felt that rooming‐in was the intervention of interest and it was more intuitive for the reader.

Intervention

Mother and infant placed in the same room immediately after birth in the case of a home birth, immediately after leaving the labour or delivery room after a normal hospital birth or from the time when the mother is able to respond to her infant (in the case of caesarean section) where the infant is either bed‐sharing by attached side‐car crib or placed in a stand‐alone cot by the bedside.

Comparison

Mother and infant are placed separately. The primary site of care of the infant is in the hospital nursery throughout the hospital stay or, in the case of deliveries at home, the infant is cared for in a separate room by someone other than the mother.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Duration of breastfeeding as measured by one of the following.

Duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

Duration of any breastfeeding.

Proportion of infants being exclusively breastfed at six months of age.

Proportion of infants being given any breastfeeding at six months of age (not pre‐specified).

Exclusive breastfeeding is defined as an infant receiving only breast milk, without any additional food or supplement.

Any breastfeeding is defined as an infant receiving any amount of breast milk, regardless of supplements.

Secondary outcomes

Frequency of breastfeeding per day.

Exclusive breastfeeding on discharge from the hospital or day four postpartum.

Maternal outcomes: breast engorgement, maternal duration of sleep, maternal adverse events (wound breakdown, puerperal sepsis, fainting episode, postpartum haemorrhage), maternal satisfaction and level of mother's confidence in breastfeeding.

Neonatal outcomes: any neonatal infection, diarrhoea, hypoglycaemia, hypothermia, significant hyperbilirubinaemia needing therapy.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (30 May 2016).

The Register is a database containing over 22,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth Group review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set which has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections: (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeJaafar 2012.

For this update, we planned to use the following methods to assess the reports identified as a result of the updated search. However, no new studies were included in this update.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For the one eligible study, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In the previous version of this review, two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for the included study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and outlined below. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for the one included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for the included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for the included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We had determined that studies would be at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for the included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for the included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for the included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for the included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether the one included study was at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update the quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparison.

Duration of any breastfeeding

Proportion of infants being exclusively breastfed at six month of age

Proportion of infants being given any breastfeeding at six months of age

Frequency of breastfeeding per day

Exclusive breastfeeding on discharge from the hospital or day four postpartum.

Maternal level of confidence in breastfeeding

Neonatal infection

We used GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create a ’Summary of findings’ table. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes were produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

Had we had encountered continuous outcomes, we planned to report the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We would have used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in this update. In future updates, if eligible for inclusion, we will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials if such trials are identified and are otherwise eligible. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a subgroup analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials are not eligible for inclusion; such trials are not appropriate for this type of intervention.

Trials with more than two arms

The trial included in this review consisted of four groups. We combined three of the groups as the intervention (rooming‐in) and the fourth group acted as the control (separate care) and analysed the results as a single pair‐wise comparison using the methods set out in the Handbook (Higgins 2011) to avoid double‐counting.

Dealing with missing data

We noted the level of attrition for the one included study. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect will be explored by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

There was only one included study in this update and so it was not possible to assess heterogeneity. In future updates, we will assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We will regard heterogeneity as substantial if the I² is greater than 30% and either the Tau² is greater than zero, or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). There was only one included study in this update. In future updates, if more studies are included, we will use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials.

If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

There was only one included study and so it was not possible to carry out planned subgroup analysis. In future updates, if we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We will carry out the following subgroup analyses to compare the differential effect of the intervention by mode of delivery (normal delivery versus caesarean section), by parity (primipara versus multipara) and by the infant sleeping allocation (bed‐sharing versus bedside cot). For this update we have added feeding schedule.

In future updates any subgroup analyses will be restricted to the primary outcomes:

duration of exclusive breastfeeding;

duration of any breastfeeding;

proportion of infants exclusively breastfed at six months of age.

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014) and report the results quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

In future updates of this review, as more data become available, we will carry out sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of trial quality. This will involve analyses excluding studies at risk of selection bias or attrition bias. Studies of poor quality (rated as 'inadequate' or 'unclear' for allocation concealment; sequence generation; or incomplete outcome assessment), will in future updates be excluded from the analysis in order to assess for any substantive difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For the previous version of this review (Jaafar 2012), the search identified 24 reports of 19 randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We included one study (four reports) (Bystrova 2008).

For this 2016 update, we identified two new trial reports, one of which is a further report of Bystrova 2008. The other report (Tateoka 2014), is in abstract form only and does not provide sufficient information to include or exclude (seeStudies awaiting classification for details). We previously referenced two reports of an excluded study (O'Connor 1980) as two separate studies and have now merged these into one.

Included studies

One trial met our inclusion criteria. This study was reported as a thesis and in four study reports. Two of these reports contributed data for analysis.

Bystrova 2008: The study was a 4 x 2 factorial design involving a total of 176 mothers who were randomly assigned to the four main treatment groups. The four treatment groups were 1) skin‐to‐skin contact at birth with rooming‐in, 2) no skin‐to‐skin contact with rooming‐in, 3) no skin‐to‐skin contact with 24 hours nursery care, and 4) no skin‐to‐skin contact with rooming‐in delayed up to three hours after birth. The overall aim of the study was to explore the role of closeness versus separation on infant and maternal outcomes, including breastfeeding outcomes. Breastfeeding outcomes on day four postpartum were reported in one of the reports. The authors reported the overall duration of 'nearly exclusive' breastfeeding as a median. In this review, we included the reported 'nearly exclusive' breastfeeding outcome as our pre‐specified outcome 'any breastfeeding'. Data for nearly exclusive breastfeeding at six months was provided by the author. We reported this as one of our primary outcome of 'any breastfeeding'.

Three reports from Bystrova 2008 reported the effect of maternity home practices on breastfeeding performance with special reference to the type of infant apparel and the long‐term effect of early contact versus separation. The most recent study report identified for this 2016 update reported on mother‐infant interactions at day four postpartum by video analysis lasting 25 to 45 minutes. Videos were analysed for their visual content using a validated assessment tool (Assessment tool for the observation of mother/infant interaction, (unpublished)) to evaluate the quality of four variables measuring aspects of mother‐infant interactions, each on a scale of one to five. Video data were available for analysis only for 151 mother‐infant dyads. Some of these observations might indirectly measure maternal confidence. However, there were no analysable data; only P values were reported.

For further details of the trial, seeCharacteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

A total of 18 trials (20 reports) were excluded. Perez‐Escamilla 1992: this trial met our objective of comparing separate care with rooming and reported our pre‐specified outcome rate of breastfeeding at discharge, eight, 70 and 135 days postpartum. However, this study was excluded because the participating mothers were not randomly assigned to separate care or rooming. There were two other non‐randomised controlled trials and neither of these met our inclusion criteria for the intervention (Elander 1986; Kontos 1978). The other 15 trials were excluded because the intervention did not meet our inclusion criteria.

For further details of the excluded studies, seeCharacteristics of excluded studies.

One study identified at this update (Tateoka 2014) was only in abstract form and there were insufficient data available to make a judgement as to whether this study met our inclusion criteria. The authors have been contacted for further information. We are waiting for a response. For details, see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

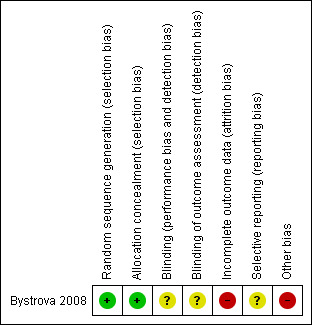

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 1 for a summary of our 'Risk of bias' assessments.

1.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

For Bystrova 2008, we judged the risk of selection bias to be low as they used a table to generate a random sequence and sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes to achieve allocation concealment.

Blinding

The authors stated that the women and researchers were blinded to the task. We judged this to be unclear. However blinding of the intervention and comparison would be extremely difficult if not impossible to achieve.

Incomplete outcome data

A total of 23 (13%) mothers were excluded from the in‐hospital analysis and the reasons for exclusion were similar across the four groups. However a total of five out of 44 (11%) dropped out after allocation because they did not want to be allocated to nursery care, and six out of 115 (5%) because they did not want rooming‐in. We judged there to be an imbalance between the groups for the reasons of attrition. There were no significant differences between the 23 mothers who were excluded and the 153 mothers who participated in the study with respect to education or the other background variables. Data were available for 78% of mothers at six‐month follow‐up. Intention‐to‐treat principle was used for those women who remained in the study.

Selective reporting

We judged this to be unclear because in the methods section of the thesis it was stated that breastfeeding duration was up to 12 months, however the results were not reported in any of the study publications, whereas other outcomes not relevant to this review were reported up to 12 months. Three‐ and six‐month data were provided on request.

Other potential sources of bias

One‐third of the women in the rooming‐in group were allocated to skin‐to‐skin contact and one‐third were able to hold their fully‐clothed infant in the labour ward after birth, whereas one‐third of the rooming‐in group and all of the separate care group did not have any contact with their infant in the labour ward. These factors could independently influence breastfeeding outcomes, apart from any intervention effect, and so we judged this to be high risk for other biases.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison: Rooming‐in versus separate mother and infant care after birth

Primary outcomes

Only one randomised trial (Bystrova 2008), involving 176 women, contributed data to the outcomes of interest, i.e. duration of any breastfeeding, frequency of breastfeeding per day and the rate of infants exclusively breastfed on discharge from the hospital. However, the trial did not report the duration of exclusive breastfeeding; the proportion of infants exclusively breastfed up to six months of age; or any of the maternal or neonatal outcomes pre‐specified in our protocol.

Duration of any breastfeeding

The overall median duration of any breastfeeding was reported to be four months. The authors stated that there was no significant difference between the groups. These data were reported as median because the distribution was skewed and so we could not include the data in any analysis.

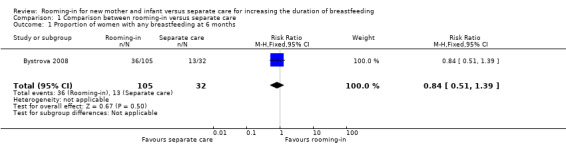

Proportion of infants being given any breastfeeding at six months of age (not pre‐specified)

There was no difference between the rooming‐in (36/105) and separate care (13/32) in the proportion of infants receiving any breastfeeding at six months (risk ratio (RR) 0.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.51 to 1.39; one trial; 137 women; low‐quality evidence), (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison between rooming‐in versus separate care, Outcome 1 Proportion of women with any breastfeeding at 6 months.

Secondary outcomes

Frequency of breastfeeding per day

The Brystrova trial reported the mean frequency of breastfeeds per day on day four postpartum for the rooming‐in group as 8.3 (standard deviation (SD) 2.2), slightly higher that the separate care group, i.e. seven times per day. However, analysis of this outcome was not done since every infant in the separate care group was breastfed at a fixed schedule of seven times per day (SD = 0) resulting in no estimable comparison.

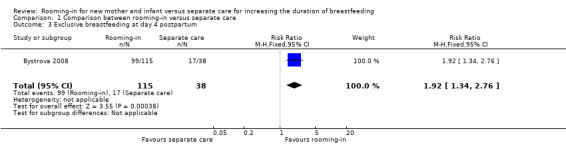

Exclusive breastfeeding at day four postpartum

The rate of infants exclusively breastfed on day four postpartum before discharge from hospital was significantly higher in the rooming‐in group 86% (99/115) compared with separate care group, 45% (17/38) (RR 1.92; 95% CI 1.34 to 2.76; one trial, 153 women; low‐quality evidence), (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison between rooming‐in versus separate care, Outcome 3 Exclusive breastfeeding at day 4 postpartum.

None of our other pre‐specified secondary outcomes were reported.

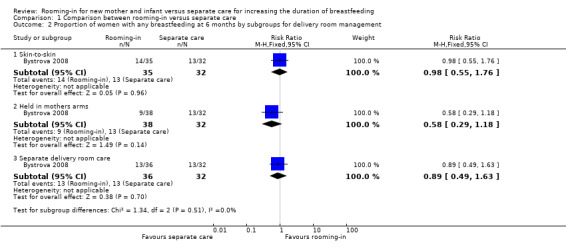

Subgroup analysis

We did not have sufficient data to perform any of our pre‐specified subgroup analyses.

However, one‐third of the women in the rooming‐in group were allocated to skin‐to‐ skin contact and one‐third were able to hold their fully clothed infant in the labour ward after birth, whereas one‐third of the rooming‐in group and all of the separate care group did not have any contact with their infant in the labour ward. These factors could independently influence breastfeeding outcomes, apart from any intervention effect, and so we judged this to be high risk for other biases. We conducted a posthoc subgroup analysis to explore the impact of the differences in labour ward management and found no differences between the three rooming‐in groups subgroups, (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison between rooming‐in versus separate care, Outcome 2 Proportion of women with any breastfeeding at 6 months by subgroups for delivery room management.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found only one randomised controlled trial (RCT) (involving 176 mother‐infant dyads) which took place in one maternity home in St Petersburg, Russia for inclusion in the review. Analysis from the available data showed mother‐infant rooming‐in significantly increased the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (day four postpartum). However, there is insufficient evidence to draw any conclusion on the effect of this on breastfeeding duration up to six months.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The search for studies for inclusion in this review was very extensive and we believe that there is only one study that addresses our question. The included RCT (Bystrova 2008) did not evaluate all the important pre‐specified outcomes, in particular it did not evaluate the proportion of infants exclusively breastfed up to six months of age as recommended by the World Health Organization. The trial examined only healthy mother‐infant pairs after a normal vaginal delivery and did not include healthy mother‐infant pairs after operative delivery as we had intended to study. In addition, they did not report any of our pre‐specified potentially harmful maternal and fetal outcomes such as rate of breast engorgement, maternal adverse events, neonatal infection, diarrhoea, and hypoglycaemia.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence is severely limited by the inclusion of only one small study. We were unable to conduct GRADE quality assessments on five of our seven GRADE outcomes (duration of any breastfeeding; proportion of infants being exclusively breastfed at six month of age; frequency of breastfeeding per day; maternal level of confidence in breastfeeding; neonatal infection). The study reported nearly exclusive breastfeeding at six months. We judged this to be similar enough to our outcome, any breastfeeding. The authors stated that exclusive breastfeeding was rare in their setting. Nearly exclusive breastfeeding was defined as breastfeeding plus irregular supplementation of juices and solids less than 30 mL per day and formula less than 100 mL per day. We assessed the two outcomes proportion of women with any breastfeeding at six months (nearly exclusive breastfeeding) and exclusive breastfeeding at day four postpartum as being of low‐quality evidence. We downgraded both outcomes to low quality because the evidence was derived only from this one small study, and secondly for risk of bias. We judged the study to be at high risk of attrition bias and for other biases arising from differences in labour ward management between the groups. These differences could have had an independent effect on our pre‐specified outcomes. However, we conducted a posthoc subgroup analysis to explore the impact of the differences in labour ward management. We found no differences between the three rooming‐in groups subgroups.

Potential biases in the review process

We attempted to minimise bias during the review process by having two people assess the eligibility of studies, assess risk of bias and extract data with a third person involved to check or review each area. We attempted to be as inclusive as possible in our search. We introduced the outcome proportion of infants being fed any breastfeeding at six months for this update. This is a post hoc decision which we made after we had completed our search and the decision is partly based on the outcomes reported in the included trial but also based om outcomes reported in the other Cochrane reviews reporting duration of breastfeeding.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We did not find any other review on this topic. A non‐randomised study (Perez‐Escamilla 1992) found a higher rate of breastfeeding at four months for primiparous but not multiparous women who received rooming‐in but not separate care.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found little evidence to support or refute the practice of mother‐infant rooming‐in or separation post delivery.

Implications for research.

There is a need for a properly designed randomised controlled trial in this field to support or refute the practice of mother‐infant rooming‐in after delivery for increasing duration of breastfeeding. Proper randomisation including concealed allocation and blinding of outcome assessors, and complete or near complete follow‐up are crucial. The intervention should be rooming‐in for the entire duration of hospital stay as defined by the World Health Organization and outcome measures should include duration of exclusive breastfeeding and proportion of infants with exclusive or any breastfeeding to six months as well as the other secondary outcomes in this review. Consideration should be given to standardising the placement of the cot for the rooming‐in mother‐infant pair. In addition to a randomised controlled trial, it would be important to explore the process of rooming‐in, using qualitative methods. This would provide insight into social and environmental factors that may support or hinder this practice.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 May 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Search updated and two new reports were identified. One report was an additional report of the included study (Bystrova 2008) and one is awaiting classification (Tateoka 2014). |

| 30 May 2016 | New search has been performed | Title has changed from Separate care for new mother and infant versus rooming‐in for increasing duration of breastfeeding to Rooming‐in for new mother and infant versus separate care for increasing the duration of breastfeeding. We have incorporated a 'Summary of findings' table in this update. A new outcome has been added for this update, Proportion of infants being given any breastfeeding at six months of age; data relating to this outcome have been added. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2007 Review first published: Issue 9, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the SEA‐ORCHID group and members of the Cochrane Australasian Centre. We would like to thank Ksenia Bystrova for providing additional data for the Bystrova 2008 trial.

This research was supported by a grant from the Evidence and Programme Guidance Unit, Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, World Health Organization. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner whatsoever to WHO.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Comparison between rooming‐in versus separate care.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion of women with any breastfeeding at 6 months | 1 | 137 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.51, 1.39] |

| 2 Proportion of women with any breastfeeding at 6 months by subgroups for delivery room management | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Skin‐to‐skin | 1 | 67 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.55, 1.76] |

| 2.2 Held in mothers arms | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.29, 1.18] |

| 2.3 Separate delivery room care | 1 | 68 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.49, 1.63] |

| 3 Exclusive breastfeeding at day 4 postpartum | 1 | 153 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.92 [1.34, 2.76] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bystrova 2008.

| Methods | This is a randomised controlled trial with 4 x 2 factorial design. The factorial design takes into account 2 factors, i.e. infant location in relation to the mother and the type of infant apparel. Randomisation took place immediately after birth. Data were recorded in the delivery ward 25‐120 minutes postpartum and later in the maternity ward. St Petersburg, Russia. |

|

| Participants | 176 (separate care: 44, rooming‐in:132) healthy mother‐infant dyads after normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. 23 participants excluded (separate care: 6, rooming‐in: 17) leaving total of 153 (separate care: 38, rooming‐in: 115) mother‐infant pairs for study all of whom were included in the short‐term outcomes up to discharge from hospital (on day 4 postpartum). Data for 6 months breastfeeding outcome were available for 137 mothers (135 rooming‐in, 32 separate care mothers) | |

| Interventions | Group 1 infants (n = 37) were placed skin‐to‐skin on their mother's chest 25‐120 minutes after birth, while still in the labour ward and later were dressed in clothes and taken to the maternity ward for rooming‐in with their mother. Group 2 infants (n = 40) were dressed and placed in their mother's arm 25‐120 minutes after birth and then taken to the maternity ward for rooming‐in with their mothers. Group 3 infants (n = 38) were dressed and kept in the cot at the labour ward nursery 25‐120 minutes after birth and stayed in the nursery while their mother was in the maternity ward until discharged from the hospital. Group 4 infants (n = 38 ) were dressed and kept in the cot at labour ward nursery 25‐120 minutes after birth and later were taken for rooming‐in with their mothers. We analysed group 3 as the control group (separate care) and group 1, 2 and 4 as the experimental group (rooming‐in). In the rooming‐in group, the mothers were encouraged to breastfeed their infants on demand while in the separate care group, the infants were taken to their mothers' room in the maternity ward at a fixed schedule of 7 times a day for breastfeeding. |

|

| Outcomes | Primary breastfeeding outcomes: breastfeeding parameters on day 4 postpartum, i.e. frequency of breastfeeding per day, duration of each feed (minutes), volume of milk ingested (mL), infant weight changes (g) and rate of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge. Secondary outcomes: median duration of 'nearly exclusive' breastfeeding, and mother‐infant interaction 1 year later using The Parent‐Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA) Method. 'Nearly exclusive' breastfeeding is analysed as any breastfeeding in this review. The paper included in this update used a validated tool with 14 observations to assess mother‐infant interaction at day 4. Some of the elements on this tool might be considered as indirect measures of maternal confidence. |

|

| Notes | This thesis was reported in a total of 5 study reports (only 2 study reports contributed data to this review). Due to skewing of the data the duration of breastfeeding was analysed as a median and interquartile range. The mean and SD was supplied by the author who warned a skewed distribution of data. The author also supplied 'nearly exclusive breastfeeding' outcomes at 6 months. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A table of allocation sequence was drawn up in advance of the trial. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | The mother‐infant pairs were randomly assigned according to allocation sequence using sealed opaque sequentially numbered envelopes for primiparas and multiparas. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It was reported that both "the researchers and the recruited women were blinded to the task". The method of blinding used for women and researchers was not stated. Comment: It would be extremely difficult to blind this intervention. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | The method of blinding of outcome assessors was not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 23/176 (13%) of the mother‐infant pairs excluded from the trial post randomisation, (6/38 (15%) from the separate care group and 18/138 (13%) from the rooming‐in group. The number of exclusions and reasons for exclusion were similar across the 4 groups. However a higher proportion of exclusions in the separate care group, 5/44 (11%) compared with 6/115 (4%) in the rooming‐in groups were due to refusal of treatment allocation. At 1‐ 3‐ 4‐ and 6‐months follow‐up there were 32 and 105 in the 2 respective groups (19.9%). Those included in the 6‐month outcomes were analysed by an intention‐to‐treat principle. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The methods section of 1 paper stated that breastfeeding duration was studied at intervals up to 12 months, however results were not reported in any of the study publications. |

| Other bias | High risk | Women in the rooming‐in group had 1 of 3 different treatments in the labour ward i.e. skin‐to‐skin contact, holding dressed baby in her arms immediately after delivery and removal of the baby form the mother during stay in the labour ward. These treatments could have independently influenced the outcome so that any effect seen in the rooming‐in group might not be attributable to the rooming‐in intervention. |

SD: standard deviation

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by year of study]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Greenberg 1973 | This is a randomised controlled trial of 100 primiparous mothers who had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery. 50 mothers were assigned to room‐in and the infant was brought to the mother within 12‐36 hours after birth and remained in a cot from 9 am to 6 pm and later returned to the nursery. The other group of the mothers were assigned to a nursery care unit where their infants were placed in the open nursery. The outcomes measured in this study were mother's level of confidence and level of competence prior to leaving the hospital. In this study, rooming‐in did not meet our defined rooming‐in criteria. |

| Sousa 1974 | This trial reported only in abstract form, comparing separate care and rooming‐in, is not clear how the mother‐infant pairs were assigned. 200 mother‐infant pairs were recruited after a normal vaginal delivery. 'Successful lactation' up to 2 months was measured. |

| Sosa 1976 | This is a randomised controlled trial of 160 primiparous mothers to determine the physical benefits of early mother‐infant skin‐to‐skin contact. The mothers in the experimental groups had skin‐to‐skin contact with their infants at birth followed by rooming‐in for only 45 minutes before the infants were placed in the nursery for their remaining hospital stay. The outcomes measured in this study were mean duration of breastfeeding in the first year, the rate of breastfeeding up to 1‐year postpartum, affectionate behaviour, rate of infection and infant growth. In this study, rooming‐in did not meet our pre‐defined rooming‐in criteria. |

| Hales 1977 | This is a randomised trial of 60 healthy primiparous mothers to assess the effect of mother‐infant skin‐to‐skin contact after birth on mothers' affectionate behaviour towards the infants. Mothers were assigned to 3 groups, i.e. early skin‐to‐skin contact, delayed contact and controls, The study did not meet our inclusion criteria as it did not study rooming‐in. |

| Kontos 1978 | This non‐randomised trial examined the effect of extended contact in the early postpartum hours and days on maternal attachment behaviour at 1 and 3 months. The study comparison group did not meet our pre‐specified criteria of rooming‐in. |

| Ali 1981 | This randomised trial examined the effects on later behaviour of a 45‐minute period of contact immediately after birth between a woman and her full‐term healthy newborn. A total of 100 mothers from a low‐income group were recruited after uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Half (50) of the mothers were randomly assigned to the study group where they were allowed contact with their infants for 45 minutes, followed by separate care for 9 hours before re‐establishing contact. Both the intervention and comparison did not meet our pre‐specified inclusion criteria. |

| Grossmann 1981 | This randomised controlled trial examined the effect of early and/or extended mother‐infant tactile contact. This study did not meet any of our pre‐specified inclusion criteria. |

| Elander 1986 | The design of this study is quasi‐random. However, the authors did not fully comply with allocation in that some participants were allocated by convenience. A total of 29 infants undergoing phototherapy to treat jaundice were alternately selected into separated care (infant was transferred to pediatric ward for treatment of jaundice and mother in maternity ward) and non‐separated (both mothers and her infants were transferred to the pediatrics ward when bed was available). However, when there was no empty single room available for rooming‐in the infant was assigned to the separate care group. The age of the infants at allocation and the type of care prior to allocation was not described. |

| Lind 1986 | In this study, 344 primiparas after uncomplicated vaginal delivery of term infants with birthweights of 3000 g to 4000 g were recruited and randomly selected to a rooming‐in group (n = 172) where the newborns stayed with the mothers during the day time and returned to nursery during the night. The comparison group (n = 175) had separate care in the nursery until discharge. At discharge mothers completed questionnaires on duration of exclusive and any breastfeeding during the hospital stay. The study did not meet our pre‐specified inclusion criteria for rooming‐in. |

| Keefe 1986 | This randomised trial compared the state of behaviour of newborns who were rooming‐in with their mothers at night with those who were cared for in the traditional nursery at night. During the day all the infants were cared for in the nursery. The study comparison group did not meet our pre‐specified criteria for rooming‐in. |

| Lindenberg 1990 | The study was carried out over 2 time periods. Women were assigned to separate care during the first time period and to rooming‐in for the second time period. Women during the first period were randomised to 2 different types of separate care. The outcome reported measured was incidence of breastfeeding at 1 week and 4 months. |

| Perez‐Escamilla 1992 | This trial was a non‐random controlled comparison of rooming‐in versus nursery care. 58 eligible women who delivered in Hospital A were assigned to nursery care and compared with 107 women assigned to rooming‐in in Hospital B. The women in Hospital B were randomised to rooming‐in and rooming‐in with breastfeeding guidance. The outcome measured was duration of full and any breastfeeding. This study reported a significantly higher breastfeeding rate at 4 months among primiparae who had a childbirth at the rooming‐in hospital and received breastfeeding guidance. |

| Segura‐Millan 1994 | This randomised trial aimed to evaluate a maternity ward breastfeeding promotion programme and to identify factors related to perceived insufficient milk. Women were interviewed in the hospital, at 1 week, 2 months and 4 months postpartum for factors associated with perceived insufficient milk. This study did not meet our inclusion criteria. |

| Kastner 2005 | This randomised trial aimed to evaluate the impact of a first hour postpartum mother‐infant contact on the mother‐child relationship during the puerperium period. Immediately after delivery the mother‐infant pairs were assigned either to a group where mother and child spent the first hour alone and the control group which followed labour room routine practice. This trial did not study rooming‐in versus separate care of mother‐infant pairs. |

| O'Connor 1980 | This 'randomised' trial examined the effect of rooming‐in on the incidence of measures of parenting inadequacy. A total of 301 mother‐infant pairs were studied. The randomisation and allocation was based on the availability of the rooming‐in beds in the postnatal ward. When both type beds were available, there was no information about how mothers were assigned to the postnatal beds. About 143 mothers were assigned by the bed availability to rooming‐in (n = 143), where the infants were roomed‐in with their mothers 7 hours after birth up to 8 hours each day until discharge. The other 158 mother‐infant pairs had separate care after a glimpse of their baby at birth. Parental inadequacy was measured after 17 months by the rate of infestations, rate of accident, exanthematous disease and hospitalisation. Rooming‐in in this study did not meet our definition of rooming‐in where the infants are expected to stay with mother in the same room or in nursery for 24 hours a day. |

| Ball 2006 | This randomised trial examined the effect of 3 rooming‐in practices on the initiation of breastfeeding and infant safety. There was no separate care group. |

| Ball 2011 | This study compared the effect on breastfeeding duration of side‐car cribs with stand alone cots in rooming‐in mother infant pairs. There was no separate care group. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Tateoka 2014.

| Methods | Randomised control trial? |

| Participants | 46 mother‐infant pairs. |

| Interventions | Mother‐infant contact after birth. |

| Outcomes | Salivary cortisol and saliva CgA level. |

| Notes | This study analysed physical and psychological stresses from the participant 60‐120 minutes after birth. It does not measure any of the outcome pre‐specified in our review. We have contacted the author for the details and awaiting for his reply. |

CgA: chromogranin A

Differences between protocol and review

The methods have been updated in accordance with the latest guidelines (Higgins 2011) and standard methods text for Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth review group.

For this update (2016), we have reversed the intervention and the comparison. We have taken rooming‐in as our intervention and separate care as the comparison. Since both rooming‐in and separate care are traditional practices we have made this change because we felt that rooming‐in was the intervention of interest and it was more intuitive for the reader. We added the outcome, Proportion of infants being given any breastfeeding at six months of age. We also conducted a posthoc subgroup analysis to explore the impact of the differences in labour ward management of the three rooming‐in groups.

Feeding schedule has been added as a new subgroup within the methods section on Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity.

Contributions of authors

Sharifah Halimah (SHJ) is the main author and guarantor for the review. She wrote the first draft of the protocol; provided a clinical and policy perspective as well as providing general advice on the development of the protocol, review and update. For the review she assessed studies for inclusion, assessed trial quality and extracted and analysed the data and wrote the review.

Jacqueline Ho (JH) provided general comments and advice from the protocol development to the completion of the review and update. She assessed trial quality where disagreement arose in the decision to include or exclude trials.

Lee Kim Seng (LKS) helped to draft the protocol and provided a clinical perspective during protocol development as well as the review. For the review he assessed studies for inclusion and assessed trial quality.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Regency Specialist Hospital, Johor Baru, Malaysia.

Penang Medical College, Malaysia.

KPJ Ipoh Specialist Hospital, Malaysia.

External sources

SEA ORCHID Project, Malaysia.

Evidence and Programme Guidance Unit, Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, World Health Organization, Switzerland.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bystrova 2008 {published and unpublished data}

- Brystrova K, Matthiesen AS, Widstrom AM, Ransjo‐Arvidson A, Welles‐Nystrom B, Vorontsov I, et al. The effect of Russian Maternity Home routines on breastfeeding and neonatal weight loss with special reference to swaddling. Early Human Development 2007;83:29‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brystrova K, Widstrom AM, Matthiesen AS, Ransjo‐Arvidson A, Welles‐Nystrom B, Vorontsov T, et al. Early lactation performance in primiparous and multiparous women in relation to different maternity home practices. A randomised trial in St. Petersburg. International Breastfeeding Journal 2007;2:9. [DOI: 10.1186/1746-4358-2-9] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystrova K. Skin to skin contact and suckling in early postpartum: effects on temperature, breastfeeding and mother‐Infant interaction. A study in St. Petersburg, Russia [thesis]. Karolinska Institute, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bystrova K, Ivanova V, Matthiesen A, Mukhamedrakhimov R, Ransjo‐Arvidson AB, Mukhamedrakhimov R, et al. Early contact versus separation: effect on mother‐infant interaction one year later. Birth 2009;36(2):97‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas L, Lepage M, Bystrova K, Matthiesen AS, Welles‐Nyström B, Widström AM. Influence of skin‐to‐skin contact and rooming‐in on early mother‐infant interaction: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Nursing Research 2013;22:310‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Ali 1981 {published data only}

- Ali Z, Lowry M. Early maternal‐child contact: effects on later behaviour. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 1981;23:337‐45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ball 2006 {published data only}

- Ball H. Sleeping and feeding in the first 6 months: test of a large‐scale data collection technique. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 2004;22(3):231. [Google Scholar]

- Ball HL, Ward‐Platt MP, Heslop E, Leech SJ, Brown KA. Randomised trials of infant sleep location on the postnatal ward. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2006;91(12):1005‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ball 2011 {published data only}

- Ball HL, Ward‐Platt MP, Howel D, Russell C. Randomised trial of sidecar crib use on breastfeeding duration (NECOT). Archives of Disease in Childhood 2011;96(7):630‐4. [PUBMED: 21474481] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Elander 1986 {published data only}

- Elander G, Lindberg T. Hospital routines in infants with hyperbilirubinemia influence the duration of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica 1986;75(5):708‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Greenberg 1973 {published data only}

- Greenberg M, Rosenberg I, Lind J. First mothers rooming‐in with their newborns: its impact upon mother. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 1973;43:783‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grossmann 1981 {published data only}

- Grossmann K, Thane K, Grossmann KE. Maternal tactual contact of the newborn after various postpartum conditions of mother‐infant contact. Developmental Psychobiology 1981;19:454‐61. [Google Scholar]

Hales 1977 {published data only}

- Hales DJ, Lozoff B, Sosa R, Kennell JH. Defining the limits of maternal sensitive period. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 1977;19:454‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kastner 2005 {published data only}

- Kastner R, Gingelmaier A, Langer B, Grubert T, Hartl K, Stauber M. Mother‐child relationship before, during and after birth [Die Mutter‐Kind‐Beziehung pranatal, unter der Geburt und postnatal]. Gynakologische Praxis 2005;29(1):109‐14. [Google Scholar]

- Kastner R, Gingelmaier A, Langer B, Grubert TA, Hartl K, Stauber M. Mother‐child relationship before, during and after birth [Die Mutter‐Kind‐Beziehung pranatal, unter der Geburt und postnatal]. Padiatrische Praxis 2005;67(1):13‐8. [Google Scholar]

Keefe 1986 {published data only}

- Keefe MR. Comparison of neonatal nighttime sleep‐wake patterns in nursery versus rooming‐in environments. Nursing Research 1987;36:140‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kontos 1978 {published data only}

- Kontos D. A study of the effects of extended mother‐infant contact on maternal behaviour at one and three months. Birth and the Family Journal 1978;5(3):133‐40. [Google Scholar]

Lind 1986 {published data only}

- LInd J, Jaderling J. The influence of "rooming‐in" on breastfeeding. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica 1986;159:167. [Google Scholar]

Lindenberg 1990 {published data only}

- Lindenberg CS, Artola RC, Jimenez V. The effect of early post‐partum mother‐infant contact and breast‐feeding promotion on the incidence and continuation of breast‐feeding. International Journal of Nursing Studies 1990;27(3):179‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Connor 1980 {published data only}

- O'Connor S, Vietze PM, Sherrod K, Sandler H, Altemeier W. How does rooming‐in enhance the mother‐infant bond?. Pediatrics 1980;66:176‐82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor S, Vietze PM, Sherrod KB, Sandler HM, Altemeier WA. Reduced incidence of parenting inadequacy following rooming‐in. Pediatric Research 1980;66:176‐82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Perez‐Escamilla 1992 {published data only}

- Perez‐Escamilla R, Segura‐Millan S, Pollitt E, Dewey K. Effect of the maternity ward system on the lactation success of low‐income urban Mexican women. Early Human Development 1992;31:25‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Segura‐Millan 1994 {published data only}

- Segua‐Millan S, Dewey KG, Perez‐Escamilla R. Factors associated with perceived insufficient milk in urban population in Mexico. Journal of Nutrition 1994;124(2):202‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sosa 1976 {published data only}

Sousa 1974 {published data only}

- Sousa PLR, Barros FC, Gazale RV, Begeres RM, Pinheiro GN, Menezes ST, et al. Attachment and lactation. Proceedings of 14th International Congress of Pediatricia; 1974; Buenos Aires, South America. 1974:136‐8.

References to studies awaiting assessment

Tateoka 2014 {published data only}

- Tateoka Y, Katori Y, Takahashi M. Effect of early mother‐child contact immediately after birth on delivery stress state. International Confederation of Midwives 30th Triennial Congress. Midwives: Improving Women’s Health; 2014 June 1‐4; Prague, Czech Republic. 2014:P188.

Additional references

Bergman 2013

- Bergman J, Bergman N. Whose choice? Advocating birthing practices according to baby’s biological needs. Journal of Perinatal Education 2013;22(1):8‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bigelow 2012

- Bigelow AE, Power M, MacLellan‐Peters J, Alex M, McDonald C. Effect of mother/infant skin‐to‐skin contact on postpartum depressive symptoms and maternal physiological stress. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 2012;41(3):369‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bigelow 2014

- Bigelow AE, Power M, Gillis DE, MacLellan‐Peters J, Alex M, McDonald C. Breastfeeding, skin‐to‐skin contact, and mother‐infant interactions over infants’ first three months. Infant Mental Health Journal 2014;35(1):51‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bramson 2010