Abstract

Background

Although digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) offer a potential solution for increasing access to mental health treatment, their integration into real-world settings has been slow. A key reason for this is poor user engagement. A growing number of studies evaluating strategies for promoting engagement with DMHIs means that a review of the literature is now warranted. This systematic review is the first to synthesise evidence on technology-supported strategies for promoting engagement with DMHIs.

Methods

MEDLINE, EmbASE, PsycINFO and PubMed databases were searched from 1 January 1995 to 1 October 2021. Experimental or quasi-experimental studies examining the effect of technology-supported engagement strategies deployed alongside DMHIs were included, as were secondary analyses of such studies. Title and abstract screening, full-text coding and quality assessment were performed independently by two authors. Narrative synthesis was used to summarise findings from the included studies.

Results

24 studies (10,266 participants) were included. Engagement strategies ranged from reminders, coaching, personalised information and peer support. Most strategies were disseminated once a week, usually via email or telephone. There was some empirical support for the efficacy of technology-based strategies towards promoting engagement. However, findings were mixed regardless of strategy type or study aim.

Conclusions

Technology-supported strategies appear to increase engagement with DMHIs; however, their efficacy varies widely by strategy type. Future research should involve end-users in the development and evaluation of these strategies to develop a more cohesive set of strategies that are acceptable and effective for target audiences, and explore the mechanism(s) through which such strategies promote engagement.

Keywords: digital interventions, eHealth, systematic review, mental health, engagement

Introduction

Digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) are increasingly being recognised as effective, scalable solutions that can help to treat a range of mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, substance abuse and suicide ideation for both youth and adult users.1–4 Due to the ubiquity of technology ownership and increasing rates at which people are turning to digital platforms for mental health support,5,6 DMHIs offer an unprecedented opportunity to extend traditional mental health services to people who may be unable, or unwilling, to access them. The increasing investment in developing new models of care that harness advancements in technology is evidence of a widespread belief that leveraging technology is core to being able to meet the demand for mental health services into the future. 7

Despite the potential of DMHIs to address access to service gaps and/or enhance existing treatments, we are yet to see the routine integration of these interventions in health, education and community settings where they can reach individuals in need.7,8 This implementation lag is, in part, because clinicians will require stronger evidence that DMHIs work before these are offered as part of treatment-as-usual, and in part, because the evidence suggests that user engagement is typically poor.9,10 A recent meta-analysis of 10 randomised controlled trial (RCT) studies found that approximately only 30% of users completed 75% or more of their assigned DMHI. 11 Another meta-analysis that examined intervention attrition rates in 11 RCTs found that participants assigned to the DMHI were more likely to drop out the intervention than those assigned to a waitlist or attentional control group. 3 Given that engagement is a core component of the effectiveness of DMHIs,12–14 solving how to improve barriers to engagement is an important focus if we are to see DMHIs integrated routinely into real-world settings. 15

In recognition of issues of low engagement with digital interventions, there has been an increase in the number of studies examining the efficacy and acceptability of different engagement strategies over the past 10 years. 16 This research can be broadly classified into two categories. One group of studies has investigated the efficacy of various features within digital interventions themselves that could promote engagement. These features are generally grounded in principles of persuasive system design (PSD) – a framework that has been used to guide the design of technology-based services aimed at changing users’ attitudes or behaviours17,18 – or incorporate game-like strategies aimed at encouraging user interactivity and continued intervention use. 19 The other group of studies has examined the utility of technology-supported strategies which are not part of the digital intervention but implemented alongside the latter. These strategies generally include reminders, feedback, coaching and peer support delivered to users via the Internet (e.g. email, web-based software) or telephone (e.g. call, text message), with dissemination usually managed by a healthcare professional or an automated system.16,20 The present review focuses on this latter group of strategies because greater empirical attention has already centred on the first group of strategies.17,18

To date, only one systematic review by Alkhaldi and colleagues 16 has examined the effectiveness of external technology-supported strategies in promoting user engagement with digital interventions aimed at improving either physical or mental health. They found that technology-supported strategies showed modest effects in promoting engagement compared to when no strategies were employed, as indicated by app-obtained engagement metrics such as the number of completed modules or activities, number of features accessed, number and frequency of log-ins or page views or time spent. However, as only eight of the 14 digital interventions included in that review were specifically targeting mental health, it was difficult to draw conclusions about the role of these strategies in improving engagement among interventions addressing mental health. Users with mental health problems may find it difficult to remain engaged with interventions as a result of mental fatigue and heightened stigma-related concerns. 21 Strategies that may work for users of digital interventions targeting physical health might not be generalisable to users of DMHIs. Evidence of the effectiveness of engagement strategies in the context of DMHIs remains inconclusive on the basis of prior reviews. A review of the current state of evidence is therefore warranted. By focusing on DMHIs only, this study extends on prior reviews of this general topic area. The specific aims of this narrative synthesis are to: (i) provide an overview of the types of technology-supported engagement strategies used to promote engagement with DMHIs, and (ii) describe the effectiveness of these strategies in promoting engagement.

Method

This study adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines 22 and is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020209380).

Search strategy

Four databases were searched from 1 January 1995 (when the first journal of internet interventions was published) to 1 October 2021: MEDLINE, EmBASE, PsycINFO and PubMed. The initial search strategy was built using Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and keywords from a test set of five papers meeting study inclusion criteria that were obtained via manual search. Search terms were centred around four conceptual blocks: (i) engagement/adherence, (ii) digital interventions, (iii) mental health and (iv) study design. The final search strategy (refer Supplementary Material, Appendix 1) was developed and tested in MEDLINE. It achieved 100% sensitivity against the test set and was subsequently adapted for use in the other databases. Articles in languages other than English and grey literature were excluded.

Screening and selection

All citations were downloaded to Endnote X9 (Thomson Reuters) and duplicates were removed. Screening (titles and abstracts, and full text records) was conducted by two authors (DZQG and LM). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion at each stage and, where necessary, a third author (MT) was consulted. Inter-rater consensus for full text screening was acceptable (κ = 0·80, p < 0.01).

Inclusion criteria

Experimental (e.g. RCT, micro-randomised trial) or quasi-experimental studies which compared levels of engagement (operationalised as: the percentage of participants attaining a certain level of completion specified by the study authors; number of activities/modules completed; number and frequency of log-ins/site visits/page views; or time spent logged on) between DMHI users who received an engagement strategy with another group of users who do not receive that strategy were included. Studies that tested variations of a particular strategy (e.g. different types of reminder messaging), or explored the cumulative effect of multiple strategies were also included. Studies with three or more treatment arms were eligible if they compared the effectiveness of (i) multiple types of engagement strategies, or (ii) alternative variations of one specific engagement strategy (e.g. types of text messaging content).

Exclusion criteria

To improve comparability, we excluded studies examining interventions that (i) were aimed at helping caregivers or health professionals care for individuals with mental health difficulties, (ii) consisted only of information or self-management activities (e.g. journal, mood tracking) without any therapeutic content, or (iii) delivered by other digital media (e.g. fully text-based interventions, pre-recorded videos, DVD).

Studies were also not eligible if engagement strategies were examined in relation to non-digital interventions, if digital interventions did not primarily target mental health outcomes, or if engagement with DMHIs was measured using subjective methods (e.g. self-reported use) rather than objective methods (e.g. usage-related information that is digitally recorded on an app or digital device at the source of its origin).

Participants

There were no restrictions on characteristics pertaining to participants (e.g. age, race, gender), population (e.g. adult, youth) or setting (e.g. clinical, community).

Interventions

DMHIs had to deliver manualised therapeutic content via a technology-based medium such as the Internet or smartphone. There were no restrictions on mental health condition(s) targeted by DMHIs. Restrictions on the characteristics of DMHIs have been covered in the exclusion criteria.

Comparators

Comparator groups for eligible studies were those in which participants received one of the following: (i) little or no engagement support, (ii) engagement strategies that were not delivered using technology (e.g. face-to-face human support, physically mailed reminders) or (iii) alternative variations of a specific technology-supported engagement strategy.

Outcomes

The main outcome of interest was engagement with the DMHI, measured objectively as the number of features accessed, number of sessions/activities completed, number and frequency of log-ins/visits, time spent on the DMHI, completion/non-completion rates and rates of adherence to prescribed levels of use. Reports of one or more of these metrics are considered collectively as engagement.

Data extraction

Data from the included studies were extracted and recorded in a custom spreadsheet created using methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 23 Key study information extracted included the following: (i) study design, (ii) characteristics of the study sample, (iii) characteristics of the DMHI, (iv) characteristics of the engagement strategy, (v) how engagement was measured and (vi) main study findings. One author (DZQG) extracted and recorded data for all the included papers. This was subsequently verified by another author (LM). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, and if no consensus was achieved, a third author (MT) was consulted. Corresponding authors of studies were contacted by email for any clarification or missing information.

Risk of bias

The Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) 24 and Risk Of Bias in Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) 25 tools were used to assess the risk of bias for RCT and non-RCT studies, respectively. Each of the five risk domains of the RoB2 was scored against a three-point rating scale corresponding to a low, unclear or high risk of bias. Each of the seven risk domains of the ROBINS-I was scored against a four-point rating scale, corresponding to a low, moderate, serious, or critical risk of bias. Risk of bias ratings was conducted independently by two reviewers (DZQG and LM). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Results

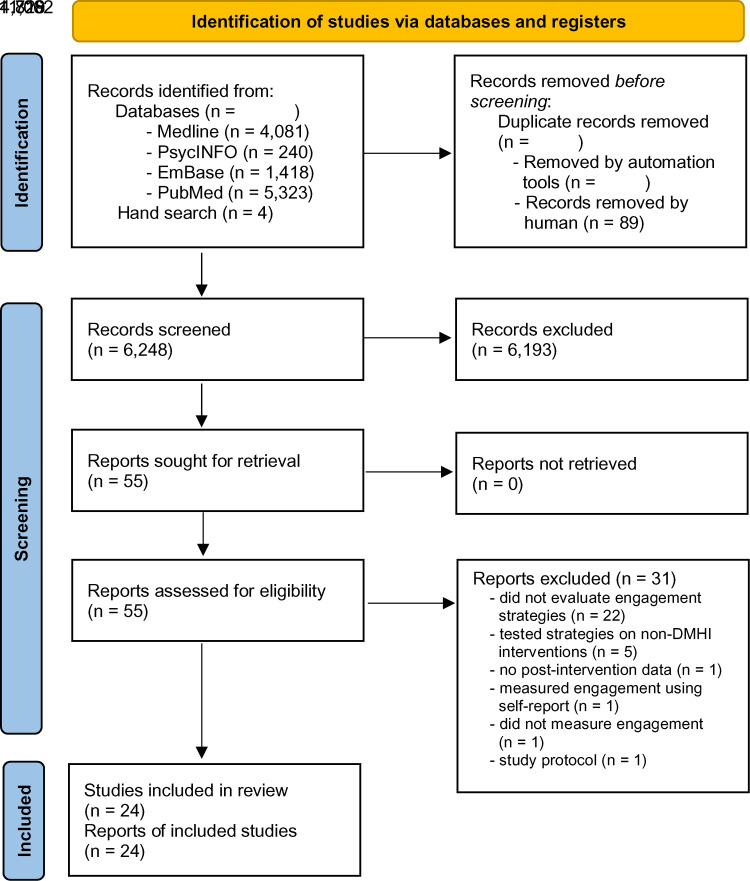

Figure 1 summarises the systematic search process. The search yielded a total of 11,066 papers. Following the removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 6248 papers were screened for inclusion. Following this, 55 papers were identified as potentially eligible and underwent full-text screening. A total of 24 papers were eligible for inclusion; 31 papers were excluded at the full-text screening stage for the following reasons: 22 papers did not empirically evaluate the effect of an engagement strategy; five papers tested engagement strategies for non-DMHI interventions; one study did not contain data on the post-intervention effects of the engagement strategy; one study used subjective self-report engagement measures; one study did not measure engagement; and one study was a protocol.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process.

Included studies

Characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. The 24 included papers contained data from 23 unique studies (N = 10,266 participants); 15 studies (62.5%) were published within the last five years (i.e. since 2016). Total sample sizes of individual studies ranged from 25 to 4561 participants (Median = 168). Most studies were RCTs (n = 20, 83.3%). Two employed quasi-experimental designs.27,33 Finally, two studies employed a micro-randomised trial (MRT) design on the same study sample.30,31 In MRTs, individuals are randomised many times over the duration of the study with the aim of examining whether the effect of the treatment component(s) of interest varies given the individual's context at each point in time. 50

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| First author, Country | DMHI name, characteristics | Primary outcome(s) & data collection time points | Study design | Treatment (Engagement strategy) arm(s) | Participant demographics* | Comparator arm(s) | Engagement strategy details | Engagement measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batterham et al. 26 , Australia | myCompass 2 14 modules, 7 weeks. Unguided. 7 modules provided core transdiagnostic CBT, whereas the other 7 provided content aimed at addressing specific mental health problems. |

Depression- and anxiety-related

symptoms Post: 7 weeks Follow-up: 19.1 weeks |

RCT | Engagement Facilitation Intervention (EFI, n = 280) |

Adults from the general population. EFI group: 54.3% aged between 36 −55yrs. 77.5% female No EFI group: 57.9% aged between 36–55yrs. 76.1% female |

No strategy (n = 285) | The EFI was developed using a participatory design approach

that involved potential end users. It consisted of brief,

tailored, written, and audio-visual content with the

following: - Feedback about the participant's symptom levels - Tailored description of the benefits of participating in DMHIs - Information about the characteristics and efficacy of myCompass 2 Provided to participants on an Internet-based platform after randomisation and before starting on myCompass 2 |

Modules started Modules completed |

| Beintner et al. 27 , Germany | IN@. CBT. 11 sessions, 39.1 weeks. Unguided. Reading assignments, email feedback, online chat with psychologist |

Symptoms of bulimia nervosa (BN) Post: 39.1 weeks Follow-up: NA |

Quasi | Telephone prompts (n = 63) | Adults diagnosed with BN, and receiving inpatient

treatment. 25.8(7.09) yrs 100% female |

Email prompts (n = 63) | 5-min calls by a research assistant at 6 time-points: 2 weeks, 2-, 3-, 4-, 6-, 8-months post-allocation. | % of all assignments completed |

| Berger et al. 28 , Switzerland | Internet-based self-help guide. CBT 5 lessons, 10 weeks. Unguided. Text-based lessons, several exercises, online diary, online discussion forum. |

Symptoms of social phobia Post: 10 weeks Follow-up: 26.1 weeks |

RCT | Emails – standard (n = 27) Emails – optional (n = 27) |

Adults aged 18 and above. Self-report meeting cut-off on at least 1 of 2 social anxiety measures. Email: 36.9(11.6)yrs 48.1% Female On-demand: 37.4(11.4)yrs 55.6% Female |

No strategy (n = 27) |

Email support: Weekly email feedback by therapist Access to

email contact with therapist Optional: start with no emails. Provision of support upon request |

Lessons completed |

| Berger et al. 29 , Switzerland & Germany | Deprexis. CBT 11 modules, 10 weeks. Unguided. Each module imparts concepts and techniques, engages the user through exercises and response prompts. |

Depression-related symptoms Post: 10 weeks Follow-up: 26.1 weeks |

RCT | Email prompts (n = 25) | Adults aged 18 and above. Self-reporting at least mild

depressive symptoms 38.2(15.1)yrs 68% Female |

No strategy (n = 25) |

Weekly therapist emails with feedback based on participants’ program usage over the previous week. | Modules completed |

| Bidargaddi et al. 30 , Australia | JOOL. Behaviour modification. 12 weeks.

Unguided. Feedback and content recommendations are provided based on user's self-monitoring ratings. |

General mental well-being Post: NA Follow-up: NA |

Micro-randomised trial | All participants with push notifications enabled (n = 1255) | Adults. Office workers Age (yrs): <30: 28.9% 30–50: 42.4% >50: 28.7% 64.0% Female |

NA | Time-varying push notifications containing a contextually tailored message from a curated library to Push notifications randomised could be sent at 1 of 6 chosen time points throughout the day. Maximum of one message per day. | % who used app within 24hrs of receiving notification |

| Bidargaddi et al. (2018b) 31 , Australia | JOOL. Behaviour modification. 12 weeks.

Unguided. Feedback and content recommendations are provided based on user's self-monitoring ratings. |

General mental well-being Post: NA Follow-up: NA |

Micro-randomised trial | All participants with push notifications enabled (n = 1265) | Adults. Office workers Age (yrs): <30: 28.9% 30–50: 42.4% >50: 28.7% 64.0% Female |

NA | Tailored suggestions vs. tailored insights. | % who used app within 24hrs of receiving notification |

| Carolan et al. 32 , UK | WorkGuru CBT, positive psychology, mindfulness 7 modules ( + 3 optional), 8 weeks. Unguided. |

General mental well-being Post: 8 weeks Follow-up: 8 weeks |

RCT | Online discussion group

(n = 26) |

Adults. Aged 18 and above; working in a UK-based

organisation. Elevated stress levels 40.2(9.8)yrs 81% Female |

No strategy (n = 28) |

Online discussion group that was delivered via a bulletin board. Facilitated by a coach, who introduced one or more of the modules and encouraged discussion about the topic each week. Participants remained anonymous. | 1. No. of site logins 2. Modules completed 3. Page views |

| Cheung et al. 33 , USA | IntelliCare. Behavioural Intervention Technology model. 12 apps; 16 weeks. Unguided. |

Depression- and anxiety-related

symptoms. Post: NA Follow-up: NA |

Quasi-experimental | Recommender app (“Hub”; n = 1514) |

Adult 36(13)yrs 62% Female |

No strategy (n = 3047) | Hub coordinates user experience with the other IntelliCare apps, including managing messages and notifications from the other clinical apps within the IntelliCare suite and encourage exploration of new apps. | 1. Time between DL and last use 2. # sessions launched (any app) 3. # days/week with at least one session |

| Clarke et al. 34 , USA | ODIN (Overcoming Depression on the InterNet). Pure self-help program offering training in cognitive restructuring. Each chapter presents a new technique via interactive examples and practices 7 chapters, 16 weeks max. Unguided. |

Depression-related symptoms Post: 16 weeks Follow-up: NA |

RCT | Telephone prompt (n = 80) | Adults. Recruited both clinical and non-clinical populations. Identified using electronic medical records 44.4(10.5)yrs 83.8% Female |

Postcard prompt

(n = 75) |

The telephone reminder calls were <5 min and scripted to

convey information identical to that included on the

postcard reminders. Reminder staff had no mental health background, were prohibited from engaging in any therapy-like activity, and could only assist users with basic website troubleshooting. |

Frequency of log-ons. |

| Farrer et al. 35 , Australia | BluePages is a psychoeducational website that contains

information and resources related to depression. (Week

1) AND MoodGym: online CBT program for depression. Five interactive modules released sequentially. (Weeks 2-6). Unguided. |

Depression-related symptoms Post: 6 weeks Follow-up: 26.1 weeks |

RCT | Telephone tracking (n = 45) | Adults (18 years and above) who called into a suicide

counselling

hotline. > 22 or above on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) 41.7(12.1)yrs 82% Female |

No strategy (n = 38) |

Weekly 10-min telephone call from a lay telephone counsellor, with the call addressing any issues related to participants’ use of the online programs. | 1. Visits to the BluePages site. 2. MoodGYM program modules completed (0 to 5) 3. % participants that completed all learning activities |

| Gilbody et al. 36 , UK | MoodGYM. CBT five interactive modules released sequentially and a sixth session that is predominantly consolidation. 5 weeks. Unguided. |

Depression-related symptoms Post: 17.4 weeks Follow-up: 34.8 weeks |

RCT | Telephone facilitation (n = 187) | Adults recruited from primary care.

>10 for depression

(PHQ9) 41.0(13.8)yrs 66.8% Female |

No strategy (n = 182) | 8 telephone calls conducted by a telephone support worker alongside the cCBT program within 14 weeks of first contact (and before the 4-month follow-up time point). Calls were 10–20 min long and aimed to provide motivation and address any barriers to engagement. |

Modules completed |

| Hadjistavropoulos et al. 37 , Canada | Well-being Course. CBT. 5 lessons, 8 weeks. Unguided. Individual lessons focus on: (1) the cognitive behavioural model and symptom identification; (2) thought monitoring and challenging; (3) de-arousal strategies and pleasant activity scheduling; (4) graduated exposure; and (5) relapse prevention |

Depression- and anxiety-related

symptoms Post: 8 weeks Follow-up: 13.0 weeks |

RCT | Email therapist support

(standard) n = 91 Email therapist support (optional) n = 83 |

Adults self-reporting mild-mod depression or anxiety

symptoms Standard: 38.2(11.4)yrs 82.4% Female Optional: 38.4(14.5)yrs 74.7% Female |

NA | Trained therapists were instructed to: (1) show warmth and

concern; (2) ask about patient's understanding of the

material and need for help; (3) provide feedback on outcome

measures; (4) highlight lesson content; (5) answer questions

about the lesson and assist with use of skills; (6)

reinforce progress and practice of skills; (7) manage any

risks that presented and (8) clarify and remind patients of

course instructions. Optional: no contact is offered unless the patient requests support. |

1. % patients who accessed each lesson 2. No. emails sent to therapist, 3. Emails from therapist 4. Phone calls with therapist 5. App log-ins |

| Hadjistavropoulos et al. 38 , Canada | Well-being Course. CBT. 5 lessons, 7 weeks. Unguided. Each lesson includes psychoeducational material in a slideshow format, patient stories, and downloadable lesson materials and assignments to facilitate skill acquisition. |

Depression- and anxiety-related

symptoms Post: 8 weeks Follow-up: 4, 16, 44 weeks |

RCT | Speed of email

response (one-day) (n = 233) Speed of email response (within one-week) (n = 216) |

Adults college students (18 years and

older). Self-reported depression or anxiety symptoms. 37.4(13.2)yrs 76% Female |

NA | In all conditions, the assigned therapist would send an

email to the patient on the designated day each week. In the 1BD condition, additional emails were sent within 1BD of receiving a patient email, were designed to be supportive, answer patient questions or respond to comments in patient emails |

1. % patients who accessed each lesson 2. #log-ins to app |

| Hudson et al. 39 , UK | Improving distress in dialysis (iDiD). 7 sessions, 12 weeks. Targets specific cognitive, emotional, and behavioural mechanisms associated with distress in hemodialysis. Encouraged to complete online sessions weekly with automated email reminders |

Psychological distress from dialysis

treatment Post: 12 weeks Follow-up: NA |

RCT | Telephone support calls (n = 18) | HD patients recruited from a

hospital. 49(11.4)yrs 44% Female |

No strategy (n = 7) | 30-min calls at weeks two, four, and six, all by a trained

psychological well-being practitioner (PWP). Aimed at promoting engagement with the website and CBT skills |

Sessions completed. |

| Levin et al. 40 , USA | Online ACT 12 sessions. Unguided. Website sessions that included reflection questions and writing exercises as interactive features. Content was developed by clinicians trained in ACT. Transdiagnostic approach used to cover a variety of mental health issues. |

Psychological distress Post: 6 weeks Follow-up: 4 weeks |

RCT (secondary analysis) | Phone coaching + email prompts

(n = 68) |

College students aged 18 and above. Elevated levels of self-reported psychological distress 22.3(5.08)yrs mostly female 72.4% Female No group breakdown available. |

Email

prompts (n = 68) |

All participants in active conditions received regular email

reminders (weekly). Coaching was provided by two doctoral students with one year of training in basic counselling skills, and based on an established protocol. Weekly; 5–10 mins. |

1. #sessions completed 2. % with 100% completion 3. % with at least 50% completion |

| Lillevoll et al.

41

, Norway |

MoodGYM Unguided. |

Depression-related symptoms Post: 6.5 weeks Follow-up: NA |

RCT | Tailored email

(n = 175) Standardised email (n = 176) |

High school students. No between-group demographic data |

No strategy (n = 175) |

Standard: e-mails preceding each module providing a general

introduction to the topic of each module. Tailored: based on data collected in the baseline survey on risk of depression, level of self-efficacy and self-esteem |

Adherence was measured as number of modules with 25% progression or more, with modules 2–5 collapsed to one category to increase power |

| Mira et al. 42 , Spain | Smiling is

Fun Transdiagnostic. Eight interactive modules, up to 12 weeks to complete. Unguided. Various components: motivation, psychoeducation, cognitive therapy, relapse prevention, behavioral activation component Self-help Internet-based. |

Depression-related symptoms Post: 12 weeks Follow-up: 52 weeks |

RCT | Automated phone support

(n = 36) Automated + Human phone support (n = 44) |

Adults aged 18–65years; recruited from

community Elevated levels of self-reported depression Automated: 35.2(9.70)yrs 63.9% Female Automated + Human: 35.1(9.36)yrs 65.9% Female |

NA |

Automated: biweekly automated phone messages reminding and

encouraging participants to continue with the

programme. Human: weekly 2-min call by therapist to tell participants how they are doing with their progress in the programme. No clinical content. |

Modules completed |

| Mohr et al. 43 , USA | IntelliCare. Consists of 12 clinical apps,

each targeting a specific strategy for improving symptoms of depression and anxiety, and a Hub app for consolidating user experience. 8 weeks. Unguided. |

Depression- and anxiety-related

symptoms Post: 8 weeks Follow-up: 26 weeks |

RCT | Coaching only (C)

(n = 76) Recommendations Only (R) (n = 75) Online coaching + recommendations (C + R) (n = 74) |

Community sample recruited online. 18 years and older.

Self-reported depression or

anxiety C + R: 37.6(12.2)yrs 77% Female C only: 37.1(12.3)yrs 81% Female R only: 36.2 (11.5) yrs 72% Female |

No strategy (n = 76) | Coaching: initial phone call, followed by 2–3 text

messages/week to provide encouragement, support, and check

progress. Recommendations: weekly phone notification providing recommendations to other IntelliCare apps, based on user's app use profile. |

1. Time to last use (up to 6 months) 2. App use sessions during treatment 3. #App downloads |

| Proudfoot et al. 44 , Australia | Online Bipolar Education Program (BEP) 8 module, 8 weeks. Unguided. Topics include: medications, psychological treatments, well-being plans, support networks |

Symptoms of bipolar disorder Post: 8 weeks Follow-up: 26 weeks |

RCT | Online peer support (n = 134) | Office workers aged 18–75. Age breakdown: <30: 28.9% 30–50: 42.4% >50: 28.7% No group-level demographic data |

No strategy (n = 139) |

Online coaching provided via email by people with Lived Experience of Bipolar Disorder. Aims of coaching were to help users apply skills in their lives, and answer any questions they have in managing their symptoms. | Completion of at least 4 of 8 module workbooks. |

| Renfrew et al. 45 , Australia | eLMS and a mobile app called

“MyWellness.” Theory of planned behavior (TPB) 10 modules, 10 weeks. Unguided. Interdisciplinary intervention covering a range of evidence-based strategies for enhancing mental well-being. |

General mental well-being Post: 12 weeks Follow-up: NA |

RCT | Emails only

(n = 157) Emails + Text (n = 163) Emails + Videoconferencing (n = 138) |

Adults aged 18–81 years. Non-clinical

sample. |

NA | Participants received a weekly email on the day before the

next session commencing. The email included a link to a 20

to 25 s video by the presenter, inviting them to engage with

the next presentation. S + pSMS group received automated emails plus SMS messages sent thrice weekly for the first 3 weeks, and twice weekly for the remaining 7 weeks. S + VCS group were invited to attend a synchronous, videoconference session using the app “Zoom.” A weekly timetable provided 9 different timeslots to choose from. |

1. # videos viewed 2. # challenge activities completed |

| Santucci et al. 46 , USA | Beating the Blues (BtB). CBT. 8 sessions, 8 weeks.

Unguided Web-based, imparting cognitive-behavioral strategies for the treatment of anxiety and depression. |

Depression & anxiety symptoms Post: 9 weeks Follow-up: 4 weeks |

RCT | Email reminders (n = 21) | College students who attended a university

behavioural medicine clinic. Elevated levels of self-reported depression 22.9(4.2)yrs 75% Female No between-group demographic data reported. |

No strategy (n = 22) | Weekly emails from research team reminding them to complete their BtB session for the week. | # sessions completed. |

| Simon et al.47, USA | MyRecoveryPlan 8 modules, 3 weeks. Unguided. Modules covering education, recovery plan, self-monitoring, social networking and consumer activation. |

Bipolar Disorder Post: NA Follow-up: NA |

RCT | Online peer coaching (n = 64) | Adults with bipolar disorder. No age data 72% Female No between-group demographic data |

No strategy (n = 54) | Peer specialists were people with lived experience in

bipolar disorder and completed specialised

training Participants in the coaching group were encouraged to send messages to coaches seeking additional information or support. |

Access and use of specific components of MyRecoveryPlan |

| Titov et al. 48 , Australia | cCBT. 6 lessons, 8 weeks. Unguided. Summary/homework assignment for each lesson, automatic emails and fortnightly SMS messages |

Social phobia Post: 8 weeks Follow-up: NA |

RCT | Telephone prompts (n = 84) | Adults meeting DSM-IV criteria for social

phobia. M = 41.2 years 52% Female (no group breakdown) |

No strategy (n = 84) | Weekly calls by a research assistant, at a time specified by the participant, when they were commended and encouraged to persevere but no clinical advice was offered. |

1. Adherence: complete all 6 lessons within 8

weeks 2. Mean lessons completed |

| Titov et al.49, Australia | Well-being Course. CBT. 5 lessons, 8 weeks. Unguided. Each lesson includes psychoeducational material in a slideshow format, patient stories, and downloadable lesson materials and assignments to facilitate skill acquisition. |

Depression & anxiety Post: 8 weeks Follow-up: NA |

RCT | Email prompts (n = 100) | Adults aged 18 and above with self-reported depression, GAD,

social phobia, or panic

disorder. Adults 40.3(10.1)yrs 77% Female |

No strategy (n = 106) |

All participants received email at the start. Thereafter, the Email group received at least 2 emails/week. Emails were triggered upon completion of a lesson, or non-completion of a lesson 7 days after its release. | % completed all 5 online lessons |

17 studies evaluated the effectiveness of a singular engagement strategy relative to either a non-technological engagement strategy 34 or with no engagement strategy.27–29,32–36,39–41,43,44,46–49 Seven studies explored the incremental effect of an additional engagement strategy on top of an existing engagement strategy.26,27,40,42,43,45,48 Six studies investigated characteristics of engagement strategies that may be potentially associated with their effectiveness. These included opt-in flexibility (allowing clients to opt in or out of receiving the engagement strategy),29,37 feedback response rate, 38 time of delivery, 31 type of content 30 and mode of delivery. 34

Risk of bias assessments

Risk of bias ratings for each study is provided in Supplementary Material (Appendix 2). Among the 20 RCTs, 13 studies (65.0%) had a low risk of bias relating to randomisation sequence and allocation concealment. Eight studies (40.0%) had greater than low risk of bias in deviations from the intended intervention. 14 studies (70.0%) had a low risk of bias pertaining to incomplete outcome data. All studies were rated to be at low risk for bias from outcome measurement issues. Notably, only one study was rated to have a low risk of bias for selective reporting because the other studies did not have a published trial registration or protocol with an a priori statistical analysis plan. The four non-RCT studies were each assessed to have an overall risk of bias rating of “moderate” using the ROBINS-I tool, indicating that they were methodologically sound despite not having the same level of rigour as a high-quality RCT.

Characteristics of DMHIs

DMHIs targeted a range of mental health symptoms. The primary treatment targets of DMHIs in most studies (19 studies; 79.2%) were symptoms of depression (13 studies; 54.2%), anxiety (7 studies; 29.2%) and general psychological distress (6 studies; 25.0%). In the remaining five studies (20.8%), DMHIs targeted specific mental health conditions including social phobia (two studies), bipolar disorder (two studies) and bulimia nervosa (one study). The average length of the intervention was 10.9 (SD = 6.93) weeks. 54.2% (13/24) of the studies collected follow-up data on mental health outcomes. Among these studies, the average follow-up period was 21.6 (SD = 13.3) weeks post-intervention.

Characteristics of technology-supported engagement strategies

Type. The strategies tested in the eligible studies can be broadly classified into four categories based on content: (i) brief reminders to use the app or notifications of new content to access;27,34,35,41,42,45,46,48,49 (ii) tailored suggestions, information or feedback based on participants’ baseline mental health information and/or intervention usage characteristics;26,28–31,33,41–43 (iii) peer support;32,45,47 and (iv) use of coaching techniques to increase user motivation, encourage DMHI use, facilitate learning and application of skills, provide feedback, or resolve problems impeding progress.36–40,43–45,47

Mode of dissemination. Most engagement strategies were disseminated to users via internet-based platforms such as email26,28,29,37,38,40,41,44,46,49 or telephone calls.27,34–36,39,40,42,43,48 Three studies used online discussion forums,32,45,47 three studies used text messages or in-app notifications.30,31,45 Finally, two studies based on the IntelliCare suite of apps used a companion recommender app to provide suggestions on app(s) that users could consider exploring.33,43 There was no clear pattern suggesting that certain types of strategies tended to be disseminated via a specific modality.

Frequency of dissemination. Nearly all studies utilised engagement strategies at regular intervals throughout the duration of the DMHI. The frequency of strategy dissemination ranged from once a day to once every two months. Most strategies were used once a week. Studies evaluating strategies that involved coaching43–45,47 tended to engage users between two and three times a week. Strategies that were delivered via the telephone tended to engage users at a frequency of less than once a week.27,34,36,39

Source of dissemination. Engagement strategies in 17 studies involved human dissemination. These were mostly overseen by trained mental health professionals, laypersons or coaches.28,29,32,35–39,42–47 Other personnel, such as research assistants, were responsible for this process in the remaining studies.27,34,48 The use of automated systems to disseminate engagement strategies was employed in 10 studies26,30,31,33,40–43,45,49

Effectiveness of strategies towards promoting engagement

Findings pertaining to the effectiveness of the engagement strategies for each study can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study findings split by strategy type.

| Study | Strategy | Study aim | Engagement | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reminders (n = 8) | ||||

| Beintner et al. 27 | Telephone reminder |

Incremental gains (with email prompts) |

Adherence: % of all assignments opened. | Most of the women in the telephone prompt group (67%) were reached only once or twice during the intervention period. However, overall adherence in the telephone prompt group was significantly higher than in the unprompted group (t = − 3.015, df = 124, p = 0.003). They completed significantly more assignments, used the personal goal setting feature in significantly more sessions, and filled out the symptom diary significantly more frequently than women in the unprompted group. The groups did not differ in their use of scheduled one-to-one chats (Beintner et al., Table 2). The number of successful telephone contacts was significantly correlated with overall participation (Beintner et al., Table 4). |

| Clarke et al. 34 | Telephone reminder (study staff) |

Evaluation (vs. postcard reminders) |

No. of log-ons | Participants in the two intervention groups with different reminder modes did not differ in the number of log-ons to the website (t = .45, p = 0.65) |

| Farrer et al. 35 | Telephone reminder (counsellor) | Evaluation (vs. no strategy) |

Page views Modules completed Visit duration |

No differences in average number of BluePages visits (t(81) = 0.388, p = 0.70), average visit duration (t(81) = 0.728, p = 0.47), and no. of modules completed (Mann–Whitney U = 696.0, p = 0.13) between participants in the ‘web only’ and ‘web with tracking’ conditions. |

| Lillevoll et al. 41 | Email reminder (automated) |

Evaluation (vs. no strategy) |

Adherence: number of modules with 25% progression or

more. Adherence data were coded into the following categories: (i) non-participation, (ii) one module, (iii) two or more modules |

The overall model was non-significant,

χ2(1) = 1.92, p = 0.17,

indicating that the weekly reminders did not predict

adherence. Engagement with the DMHI was very low in the overall sample. Only 8.54% (45/527) attempted at least one moodGYM module across 3 engagement and control arms. |

| Mira et al. 42 | Telephone reminder (therapist) | Incremental gains (with automated messages) |

Modules completed Treatment drop out |

There were no significant differences between the experimental groups in the drop out rate (χ2 = 0.202; df = 1; p = 0.653). |

| Santucci et al. 46 |

Email reminder (study staff) |

Evaluation (vs. no strategy) |

Sessions completed | Participants completed a mean of 3.2 sessions (SD = 2.4, range = 0–8). The mean number of sessions did not significantly differ between reminder (M = 2.9, SD = 2.5) and no reminder (M = 3.6, SD = 2.3) groups (t(41) = 0.88, ns). |

| Titov et al. 48 | Telephone reminder (RA) |

Incremental gains (with email reminders) |

Completion rates (all modules in 8 weeks) | 66 (81%) CCBT + telephone group and 56 (68%) CCBT group

participants completed all six lessons within the required

time frame

(p < 0.05). CCBT + telephone group participants completed more (M = 5.68, SD = 0.79) of the six lessons than participants in the CCBT group (M = 5.26, SD = 1.35; F(1161) = 5.95, p < 0.02). |

| Titov et al. 49 | Email reminder (automated) |

Evaluation (vs. no strategy) |

Completion rates (all modules in 8 weeks) | More TEG participants (58.0%) completed the course than TG (35.8%) participants (χ2(1) = 10.15, p = 0.001) in the Overall Sample. |

| Coaching (n = 8) | ||||

| Gilbody et al.

36

|

Telephone facilitation by trained support worker | Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

# Sessions completed | All 5 sessions completed: Intervention Group: 19.4%; Control

Group: 10.4%. 2 or more completed: Intervention Group: 46.2%; Control Group: 29.1%. No inferential stats were reported. |

| Hadjistavropoulos et al.

37

|

Email |

Characteristics (Flexibility) |

# Logins # Days spent in program # Emails exchanged with therapist % completion of lessons 4 and/or 5 |

Patients in the Standard Support group logged in more times (M = 20.57; SD = 10.33 vs. M = 15.10; SD = 10.22; Wald's χ2 = 10.43, p = 0.001) and spent more days enrolled in the program (M = 102.21; SD = 49.65 vs. M = 74.93 (SD = 47.90); Wald's χ2 = 12.22, p < 0.001), were more likely than patients receiving Optional Support to complete Lesson 4 (79/91; 86.8% vs. 57/83; 68.6%; p < 0.01) and Lesson 5 (75/91; 82.4% vs. 47/83; 56.6%; p < 0.001). |

| Hadjistavropoulos et al.

38

|

Characteristics (Response rate) |

% patients who accessed all 5 lessons Therapist contact (#emails sent/received, #calls) # Log-ins to app |

Lesson completion: χ2(2,

N = 675) = 1.13;

p = 0.57 Logins: F(2673) = 4.11; p = 0.02 |

|

| Hudson et al. 39 | Support calls by trained practitioners |

Evaluation (vs no strategy |

# Sessions completed | Adherence to online CBT sessions were lower for patients randomised to the supported arm (Median = 3, IQR = 1–5) compared with the unsupported arm (Median = 6; IQR range = 2–6). |

| Levin et al. 40 | Phone coaching by doctoral students | Incremental gains (email prompts) | 1. # Sessions completed 2. % participants with 100% completion 3. % participants with at least 50% completion |

There were no differences between the coaching and non-coaching conditions on number of sessions completed (out of 12 total), t(134) = .26, p = 0.798; Coaching M = 8.51, SD = 3.81; Non-Coaching M = 8.34, SD = 4.20, d = .04. There were also no differences between coaching and non-coaching conditions on the rate of participants completing all 12 sessions (χ2 = 0.12, p = 0.730; Coaching 43% vs. Non-Coaching 46%), or half (6) of the 12 sessions (χ2 = .16, p = 0.692; Coaching 76% vs. Non-Coaching 74%). |

| Mohr et al. 43 | Text message-based coaching | Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

Time to last use # App sessions # Apps downloaded |

Time to last use: Recommendations

(p = 0.06); Coaching

(p = 0.94) App sessions: Recommendations (p = 0.04); Coaching (p = 0.36) App downloads: Recommendations (p = 0.08); Coaching (p < 0.001) |

| Proudfoot et al. 44 |

Email-based coaching | Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

% participants who completed and returned at least 4/8 module workbooks | Adherence was significantly higher in the supported

intervention (n = 107, 79.9%) than the

unsupported (n = 96, 69.1%) intervention

(χ2 = 4.16,

p < 0.05). |

| Simon et al. 47 | Email coaching with lived experience

peers |

Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

Access and use of specific components of MyRecoveryPlan | Rates of engagement for all features of the program were higher in the coaching group, but not every comparison was statistically significant. |

| Tailored Feedback (n = 8) | ||||

| Batterham et al. 26 | Engagement facilitation Intervention |

Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

1. % of participants who started at least one

module 2. # Modules started 3. # Modules completed |

No difference (n = 565; χ2(1)

< .01; p = 0.87) between the EFI group

(in the percentage of participants who started at least one

module. No difference between EFI and no EFI groups both in the number of modules started (U = 39366.50; z = −0.32; p = 0.75) and number of modules completed (U = 39494.0; z = −0.29; p = 0.77). In general, overall module start and module completion rates were low. |

| Berger et al.

28

|

Therapist email feedback | Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

Lessons completed | Lessons completed across the three treatment

conditions were compared using Kruskal-Wallis 1-way ANOVA. No significant difference was found between the three groups, (χ2 (2) = 0.58, p = 0.75) |

| Berger et al. 29 | Therapist email feedback | Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

Modules completed | Lessons completed across the two active treatment conditions were compared using a Mann–Whitney U test No significant difference was found between the two groups (U = 240.5, p < 0.15). |

| Bidargaddi et al. 30 | Tailored health message | Characteristics | Whether the user charts in the app over a 24-h period | Users were 3.9% more likely to engage with app when a tailored health message was sent vs. not sent (risk ratio 1.039; 95% CI: 1.01–1.08; p < 0.05). Weekends > weekdays, but ns (p = 0.18). Effect of tailored message was greatest at 12:30 pm on weekends, when the users were 11.8% more likely to engage (90% CI: 1.02–1.13). |

| Bidargaddi et al.

31

|

Message type (suggestions vs insights) | Characteristics | Time of last use Frequency of use |

Overall prompts with tailored suggestions improved

likelihood of interacting with app significantly compared to

tailored insights (OR = 3.56, 95%

CI = 2.36–5.36). There was a significant interaction between message type and frequency of app use, such that sending prompts with tailored suggestions to individuals with high frequency of app use at the time of prompts significantly reduces the odds of interacting with app and monitoring (OR = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.10–0.28). We confirmed through linear regression that there were no significant independent associations between frequency of app use and type of push notifications sent. This indicates that prompts with tailored insights are better than tailored suggestions when individuals become frequent app users |

| Cheung et al. 33 | Recommendations based on previous use | Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

1. Time between DL and last use 2. # sessions launched (any app) 3. # days/week with at least one session |

Continued use – IG: 21%, CG: 11%,

p < 0.001. risk ratio for Hub users

stopping using any apps was 0.67 (95% CI: 0.62–0.71)

compared to non-Hub users, after adjusting for age, gender,

race, ethnicity, and education Hub users launched on average at least twice as many sessions per week (and up to about 5 times as many) as the non-Hub users. The increase was statistically significant at all time points. Hub users had lower odds of no activity than the non-Hub users (i.e. an odds ratio <1) after accounting for user characteristics. Hub users had higher regularity by 0.1–0.4 day per week with confidence intervals uniformly above 0. |

| Mohr et al. 43 | Recommendations based on prev use (using Hub

app) Coaching via text messaging |

Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

1. Time to last use (up to 6 months) 2. App use sessions during treatment |

Time to last use: Recommendations

(p = 0.06), Coaching

(p = 0.94) App sessions: Recommendations (p = 0.04), Coaching (p = 0.36) App downloads: Recommendations (p = 0.08), Coaching (p < 0.001) |

| Renfrew et al. 45 | Tailored

messages Videoconference |

Incremental gains (automated emails) | 1. Videos viewed (at least 80% played) 2. Challenge activities completed (Each daily challenge was worth 10 points (i.e., a total of 70 points weekly), and weekly challenges were worth 30 points.) |

The number of videos viewed was not significantly different between the groups (p = 0.42). No significant differences were recorded between the groups in the mean challenge points scored (p = 0.71) or in the mean number of weeks in which challenge scores were recorded (p = 0.66) |

| Online support (n = 2) | ||||

| Carolan et al. 32 | Online discussion group | Evaluation (vs no strategy) |

1. No. of site log-ins 2. Page views 3. Modules completed |

A medium between-group effect size was observed for the primary outcome of login (d = 0.51; 95% CI: −0.04, 1.05) and for secondary outcome page views (d = 0.53; 95%CI: −0.02, 1.07). A small effect size (d = 0.26; 95% CI: −0.28, 0.80) was observed for modules completed. |

| Renfrew et al.

45

|

Online videoconferencing support (VC) | Incremental gains VC support | 1. Videos viewed 2. Challenge activities completed |

Number of videos viewed was not significantly different

between the ‘VC + email’ group and the ‘email only’ group

(p = 0.42) Mean challenge activities completed was not significantly different between the ‘VC + email’ group and the ‘email only’ group (p = 0.71) |

Overall findings. Most studies (14/24) were RCTs that examined the efficacy of a strategy on DMHI engagement by comparing a singular engagement strategy of interest against a no-strategy comparison group. Seven studies reported higher levels of engagement in the strategy group relative to the no-strategy group on one or more measures of engagement.32,33,36,43,44,47,49 The remaining seven studies reported no differences between the strategy and no-strategy groups across all measures of engagement.26,28,29,35,39,41,46

Reminders. Eight studies investigated the efficacy of reminders in promoting engagement with DMHIs. Most delivered reminders by telephone call27,34,35,42,48 than by email.41,46,49 Four studies evaluated the effect of reminders on engagement compared to a no-strategy control group. Of these, one study reported higher completion rates in the reminder group than the control group. 49 The other three studies found no differences with their respective control groups in relation to online page views, 35 number of modules/sessions completed35,46 or overall completion rates.41,46 Three studies examined the incremental effect of telephone-delivered reminders on engagement. Of these, two reported higher completion rates among users who received telephone reminders in addition to email prompts27,48 while the remaining study found no incremental effect of telephone reminders over automated messages on rates of module completion and treatment drop out. 42

Coaching. Eight studies investigated the efficacy of coaching-based strategies in promoting engagement with DMHIs. Coaching was provided by trained practitioners, postgraduate students or peers with lived experience, and delivered to recipients via email, text message or telephone call. Five studies evaluated the effect of coaching on engagement compared to a no-strategy control group. Of these, three studies reported that coaching resulted in a greater amount of intervention content being accessed 47 or completed.36,44 One study found that coaching had no effect on the number of sessions completed. 39 Finally, one study reported mixed findings where coaching appeared to increase the amount of content accessed, but not the total number of sessions completed or duration over which the DMHI was used. 43 One study found no evidence of incremental gains in either the number of sessions completed or completion rates when telephone-based coaching was used in addition to email prompts. 40 Two studies investigated whether increasing the response rate and allowing user flexibility influenced the effect of email-based coaching.37,38 There were no differences in the number of lessons accessed and app log-ins regardless of whether therapists responded to users’ emails within one business day, or on a specific day every week. 38 In addition, users who were allowed the flexibility to opt into email-based therapist coaching had fewer log-ins, lower completion rates and spent less days using the DMHI relative to their counterparts who were assigned to receive coaching from the beginning of the intervention. 37

Personalisation. Eight studies investigated the efficacy of personalised information in promoting engagement with DMHIs. All studies offered feedback or suggestions based on users’ past programme use or individual context. These were delivered via in-app push notifications,30,31,33,43 email,28,29 internet-based platform 26 and text message. 45 Four studies evaluated the effect of tailored feedback on engagement compared to no-strategy. Of these, two examined the use of a recommender app intended for paired use with a DMHI, finding that the recommender app was effective in promoting more frequent and more sustained DMHI use over time.33,43 The other two studies which investigated the use of email-based therapist feedback both reported no effect on the number of lessons or modules completed.28,29 One study examined the incremental effect of personalised brief text messages in addition to automated weekly emails; the findings did not yield any evidence supporting the incremental utility of text messages across different intervention-related activities such as video views and challenge points scored. 45 One study found that a brief engagement intervention, used in addition to reminders, had no incremental effect on the number of modules started or completed. 26 Finally, two studies investigated whether the time of dissemination and type of content (suggestions vs. insights) of tailored health messages influenced their effectiveness in nudging users to engage with a workplace mental health app. In general, users were more likely to engage with the app when they received a health message than if they had not received it, regardless of the time of day; notably, messages sent in the early afternoon on weekends were most likely to elicit app engagement. 31 As for message content, tailored suggestions were approximately 3.5 times more likely to lead to app use than tailored insights; however, tailored insights were more effective than suggestions at eliciting app engagement among users who used the app more often. 30

Online Support Groups. Two studies investigated the efficacy of guided online support groups in promoting engagement with DMHIs. One study found that users assigned to weekly facilitated online discussion group had higher numbers of app log-ins, modules completed and page views relative to their counterparts who did not receive any strategy. 32 The other study reported no incremental effect of an online support group over automated email reminders in relation to the number of videos viewed and challenge activities completed on the intervention. 45

Discussion

This systematic review is the first to describe the characteristics of technology-supported strategies used to promote engagement with DMHIs and summarise findings pertaining to their efficacy. Engagement strategies generally involved coaching, reminders, personalised information and peer support. Most strategies engaged users throughout the intervention period through email, online forums, mobile apps or phone calls at regular intervals – usually at least once a week. Characteristics of the strategies reviewed in this paper were similar to those in the studies reviewed by Alkhaldi and colleagues. 16 Overall findings from the narrative synthesis indicated that evidence for the efficacy of technology-supported strategies in promoting engagement with DMHIs was inconclusive. Our findings also do not support the view that the use of multiple strategies has an additive effect on engagement. In addition, the results reported for each group of similar strategies were mixed. Thus, there is no evidence that a specific strategy or group of strategies is relatively more efficacious in promoting engagement than others. This contradicts previous research suggesting that human-centred strategies delivered by trained healthcare professionals, such as coaching or telephone calls, improve user engagement. 51

Studies that did not find support for the efficacy of their engagement strategy furnished several explanations for their findings. Suboptimal matching of strategies to client needs or preferences consistently emerged as a possible factor that may have hindered their effectiveness. For example, users may not have accessed strategies as intended if these were not delivered via users’ preferred medium.40,41,43 Users might also be less likely to connect with strategies pitched at a level that was not commensurate with their mental health needs. 39 In particular, reminder-based strategies may have been frowned upon by some users who perceived them as controlling 35 or lacking emotional validation. 46 Apart from one study, 26 there was no information on whether prospective users of the digital interventions were involved in developing these strategies. This absence of end-user perspectives in the design process may have had a negative impact on the potential efficacy of the strategies examined.

The studies reviewed identified a number of contextual factors that could have influenced the observed effects of engagement strategies. Although intended users of a given DMHI may have similar mental health needs, it is expected that they will differ in their preferences for the type of strategy received. 31 As a result, it is difficult to control the myriad of possible ways in which users could respond to the same strategy. For instance, engagement strategies may be successful for increasing help-seeking motivation; however, motivation may not necessarily translate into engagement with the digital intervention.41,43 Some strategies, such as those delivered via telephone call, may inadvertently provide users with convenient opportunities to discontinue with the DMHI or the research study. 35 Finally, levels of DMHI engagement in the intervention and control conditions were high in some studies,29,43 and this may have created a ceiling effect which made it difficult to detect meaningful gains in engagement that can be attributed to the strategy.

There were several variables not discussed by the studies reviewed that could have influenced engagement instead of the strategies evaluated. First, it is plausible that interactive features built directly into DMHIs for the purpose of encouraging user interaction might contribute more to engagement than the strategies discussed. 17 However, a recent meta-analytic review found that the number of in-built design elements in mHealth interventions for depression and anxiety was not positively associated with engagement. 18 The studies also did not discuss the extent to which user satisfaction with the DMHIs may have influenced engagement findings. This is important because user satisfaction with the content and design features of a DMHI may be positively associated with engagement. 52 Thus, it would not be possible to establish the effectiveness of a technology-supported engagement strategy if used in conjunction with a DMHI with poor user acceptability ratings. Following up with users who drop out of these interventions is needed to better understand the factors which might predict loss of engagement among the intended users for specific DMHIs. These insights might then be subsequently incorporated in the development of engagement strategies.

Implications

Several implications can be drawn from the findings of this review. As is the case with mental health interventions, the results suggest that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to promoting engagement with DMHIs. Tailoring of characteristics to match user's needs, preferences and profile is critical towards designing engagement strategies that are acceptable and effective. Two recent research strands that have emerged in the digital mental health space are focused on identifying user-specific characteristics 53 and intervention-specific features 18 associated with engagement. Results from such studies can be applied to the context of engagement strategies, so as to guide the design and development of strategies that are acceptable and effective to specific groups of users.

This review also highlighted two research gaps that future studies on engagement with DMHIs are recommended to address. First, research aimed at elucidating the mechanism(s) through which engagement strategies increase use with DMHIs is scarce. This was noted by some studies in this review.33,49 A recent review looking at barriers and facilitators of engagement with DMHIs and which included 208 studies highlighted that user-specific factors such as having a sense of self-efficacy, insight to their own condition, feeling that the intervention is a good fit for their needs and being able to connect with others are key factors that nudge users towards engaging with these interventions. 52 Thus, subsequent evaluations of engagement strategies should collect data assessing one or more of these potential facilitators. Also, future studies should strive to measure the extent to which a strategy was accessed by users. This is necessary as a manipulation check for treatment group(s) receiving the strategy and facilitates identification of potential dose–response associations between a given strategy and user engagement.

The existing literature is replete with examples of poorly conceptualised health research yielding outcomes of little use in meeting user needs.54,55 Collaboration with end-users should therefore constitute an essential part of the design, development and evaluation of engagement strategies for DMHIs. In the past few years, there has been growing recognition of the value of user input in the development of mental health technologies. In particular, principles of co-design – a participatory design approach whereby health professionals and end-users collaborate as equal partners – are increasingly being adopted in the design and development of digital mental health technologies, especially for younger users.56,57 There is some evidence that employing co-design approaches in the design and development of digital technologies may improve engagement by intended users. A pilot evaluation of iBobbly – an mHealth intervention that helps indigenous young people in Australia manage suicidal thoughts – found that 85% (34/40) of study participants completed all of the app's learning modules. 58 Another example of an app co-developed together with young people with lived experience of mental health difficulties is SPARX (Smart, Positive, Active, Realistic, X-factor thoughts). 59 Evaluation of SPARX revealed decent levels of engagement – close to 90% of participants completed over half of the modules, and 60% completed all modules. 59 Notwithstanding, the use of co-design methods may not always have a positive impact on user engagement. For instance, one study in this review 48 developed its strategy using a rigorous co-design process but found no effect relative to a no-strategy comparison group on all measures of engagement; however, the low overall engagement rates for the DMHI in that study suggest that engagement may be difficult to change if users do not find the intervention sufficiently engaging to begin with. In summary, the role of co-design in developing digital technologies is an emerging field with promising areas for further investigation. 56 Evaluating the impact of co-design processes on the efficacy of engagement strategies for DMHIs will be essential for establishing their value in this context.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. The studies reviewed differed in many ways, such as the type of strategy used, type of DMHI that strategies were used in conjunction with, type of engagement metrics used and research methodologies employed to assess efficacy. The strategies reviewed also differed from one another in terms of their characteristics. Due to these sources of between-study variation, exploring aggregated levels of efficacy using meta-analysis was not feasible. In addition, the number of studies that explored the effect of multiple strategies or specific characteristics within individual strategies was small, thereby preventing conclusions from being drawn. In addition, the systematic search did not include non-English language papers and grey literature. Thus, the risk of publication bias was not minimised. Notwithstanding, the earlier review by Alkaldi and colleagues 16 noted that engagement with DMHIs is an emerging field of research where both positive and null findings are equally valued.

The lack of conclusiveness in the study findings may partly be due to the broader challenges associated with operationalising engagement with digital interventions. As a result, there was considerable variation in the types of indicators used to measure engagement. The studies reviewed mostly employed system usage data (e.g. modules completed, logins, time spent in app) as indicators of engagement. These indicators are objective and tangible measures of digital technology use, and analysis of usage patterns may reveal relationships between engagement and outcomes. 60 However, they may not account for user-specific factors – such as motivation to change, actual interaction with content and offline application of content in everyday life – which may be predictive of client outcomes rather than technology usage per se. 61 As a result, it has been proposed that valid measures of engagement incorporate objective usage combined with subjective user experience elements. 61 Establishing the construct validity of engagement is a critical area of research requiring further investigation in order to elucidate the role of engagement in digital interventions. 62 Achieving a clear operational definition of engagement is an essential precursor for the standardisation of engagement-related outcome measures. In addition, future studies should also report on follow-up time points. Collectively, these steps should increase the pool of data for future meta-analyses that will help to establish the effectiveness of engagement approaches.

It was not possible to discuss the efficacy of engagement strategies in relation to differences in health condition. The mental health conditions of participants in nearly all studies were not established using formal diagnostic criteria, and there was no way to validate differences in the severity of conditions. Future studies should endeavour to account for these differences in developing engagement strategies. Specifically, users with more complex or severe psychopathology might require more simple tasks/content that minimise cognitive burden, while users with milder symptoms may have the capacity to participate in a wider range of interactive content or activities.

Finally, it is noteworthy that all of the studies reviewed were conducted prior to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. It is possible that the increased mental health burden brought about by COVID-19 may have affected how people engage with DMHIs, given the greater need for mental health support that has stemmed from this global health crisis. A further review of engagement with DMHIs will be warranted in future when more studies undertaken following the pandemic are published.

Conclusions

Strategies to improve engagement with DMHIs are undoubtedly needed if their benefits are to be fully realised. Our findings show that technology-supported strategies deployed alongside DMHIs could be effective in promoting engagement with the latter. However, more evaluation studies are needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn. Given that the lack of user input may account for the mixed findings observed across studies, it is recommended that future efforts to improve engagement with DMHIs involve end-users in the development of engagement strategies. Other areas for future research include refining the construct validity of engagement, measuring the extent to which strategies are accessed by users, exploring possible mechanisms through which the strategies of interest bring about engagement and evaluating the impact of co-design methods in developing effective engagement strategies for DMHIs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076221098268 for Technology-supported strategies for promoting user engagement with digital mental health interventions: A systematic review by Daniel Z Q Gan, Lauren McGillivray, Mark E Larsen, Helen Christensen and Michelle Torok in Digital Health

Acknowledgements

DZQG is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and a Centre of Research Excellence in Suicide Prevention (CRESP) PhD Scholarship. HC is supported by a NHMRC Elizabeth Blackburn Fellowship. MT is supported by a NHMRC Early Career Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: Lauren McGillivray, Mark E Larsen, Helen Christensen and Michelle Torok are employed by the Black Dog Institute (University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia), a not-for-profit research institute that develops and tests digital interventions for mental health.

Contributorship: DZQG, LM, MEL, HC and MT designed the study. DZQG extracted and analysed the data, with assistance from LM and MT. DZQG and LM assessed study eligibility and quality. DZQG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results, revised the initial draft critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor: MT

ORCID iD: Daniel Z Q Gan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3788-5848

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Carlbring P, Andersson G, Cuijpers P, et al. Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther 2018; 47: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linardon J, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, et al. The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry 2019; 18: 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Välimäki M, Anttila K, Anttila M, et al. Web-based interventions supporting adolescents and young people with depressive symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017; 5: e180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollis C, Falconer CJ, Martin JL, et al. Annual research review: digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems – a systematic and meta-review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017; 58: 474–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torous J, Friedman R, Keshavan M. Smartphone ownership and interest in mobile applications to monitor symptoms of mental health conditions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014; 2: e2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtis BL, Ashford RD, Magnuson KI, et al. Comparison of smartphone ownership, social media use, and willingness to use digital interventions between generation z and millennials in the treatment of substance use: cross-sectional questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e13050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreiweis B, Pobiruchin M, Strotbaum V, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of eHealth services: systematic literature analysis. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e14197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torous J, Nicholas J, Larsen ME, et al. Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone apps: evidence, theory and improvements. Evid Based Ment Health 2018; 21: 116–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews G, Basu A, Cuijpers P, et al. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: an updated meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord 2018; 55: 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleming T, Bavin L, Lucassen M, et al. Beyond the trial: systematic review of real-world uptake and engagement with digital self-help interventions for depression, low mood, or anxiety. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: e9275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karyotaki E, Kleiboer A, Smit F, et al. Predictors of treatment dropout in self-guided web-based interventions for depression: an ‘individual patient data’ meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2015; 45: 2717–2726. 2015/04/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donkin L, Christensen H, Naismith SL, et al. A systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapies. J Med Internet Res 2011; 13: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res 2005; 7: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbody S, Littlewood E, Hewitt C, et al. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy (cCBT) as treatment for depression in primary care (REEACT trial): large scale pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 2015; 351: h5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batterham PJ, Sunderland M, Calear AL, et al. Developing a roadmap for the translation of e-mental health services for depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2015; 49: 776–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alkhaldi G, Hamilton FL, Lau R, et al. The effectiveness of prompts to promote engagement with digital interventions: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18: e6. Original Paper 08.01.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelders SM, Bohlmeijer ET, Pots WTet al. et al. Comparing human and automated support for depression: fractional factorial randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2015; 72: 72–80. 2015/07/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu A, Scult MA, Barnes ED, et al. Smartphone apps for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of techniques to increase engagement. NPJ Digit Med 2021; 4: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming TM, De Beurs D, Khazaal Y, et al. Maximizing the impact of e-therapy and serious gaming: time for a paradigm shift. Front Psychiatry 2016; 7: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neff R, Fry J. Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2009; 11: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batterham PJ, Han J, Calear AL, et al. Suicide stigma and suicide literacy in a clinical sample. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2019; 49: 1136–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J 2021: 372: n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J 2019; 366: l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J 2016; 355: i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Sunderland M, et al. A brief intervention to increase uptake and adherence of an internet-based program for depression and anxiety (enhancing engagement with psychosocial interventions): randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e23029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beintner IJ, Jacobi C. Impact of telephone prompts on the adherence to an internet-based aftercare program for women with bulimia nervosa: a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv 2019; 15: 100–104. 2017/11/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]