Abstract

Suicide is death caused by injuring oneself with the intent to die. According to the 2017 National Vital Statistics report, suicide was the second leading cause of death for adolescents 10-24 years old, accounting for 19.2% of deaths in that age group. Aggregated 2015-2017 Hawai‘i Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data from 12 120 respondents were analyzed. Multivariate logistic regression modeling for complex survey procedure was created using predicted marginals to estimate crude and adjusted prevalence ratios for suicide attempts. After adjusting for race, depressive symptoms, bullying, illicit drug use, alcohol use, and self-harm, youth who experienced bullying (adjusted prevalence ratio=1.75; 95% confidence interval: 1.44-2.12), used illicit drugs (1.89; 1.54-2.31), those with one-time self-harm (2.87; 2.04-4.04), or repeated self-harm (5.31; 4.28-6.60) were more likely to have suicide attempts. Race by depressive symptoms interaction was significant (P <.01), demonstrating the heterogeneity of the stratum-specific measures of association. When depressive symptoms were present, youth who are Native Hawaiian (2.64; 1.68-4.15), Japanese (2.39; 1.44-3.95), other Pacific Islander (2.04; 1.29-3.21), Filipino (1.77; 1.21-2.59), and those who do not describe as only one race/ethnicity (1.74; 1.16-2.62) were more likely to have suicide attempts compared to White. When depressive symptoms were not present, other Pacific Islanders (4.05; 1.69-9.67), Hispanics/Latinos (3.37; 1.10-10.30), Native Hawaiians (3.03; 1.23-7.45), and other race groups (2.03; 1.03-4.00) were more likely to have suicide attempts compared to White. These results demonstrated the importance of screening for depressive symptoms and other risk factors to prevent suicide attempts in adolescents.

Keywords: Suicide attempts, risk factors, depressive symptoms, race, self-harm

Introduction

Suicide is death caused by injuring oneself with the intent to die. The effects of suicide extend beyond the person who takes his or her life. It has detrimental and lasting effects on family, friends, and communities. Although suicide occurs more frequently in older than in younger people, it is one of the leading causes of death for adolescents. According to the 2017 National Vital Statistics Report, suicide was the second leading cause of death for young people 10-24 years old, accounting for 19.2% of deaths in that age group.1 The suicide rate for this age group was stable from 2000 to 2007 but then demonstrated a significant increase from 2007 (6.8 per 100 000) to 2017 (10.6 per 100 000).2 In Hawai‘i, aggregated data from the 2015-2017 National Vital Statistics System reported that the rate of suicide deaths for adolescents aged 15-19 years was 13.2 (per 100 000), which was higher than the national estimate of 10.5 (per 100 000). Identifying the risk factors for suicide attempts for adolescents in Hawai‘i is crucial to help reduce the rate and improve adolescent health.

Past researchers have found that adolescent suicide attempt was associated with past suicide attempts, hopelessness and depressive symptoms, impulsivity, aggressive behavior, or exposure to violence.3-6 For example, a review conducted by Bilsen (2018) suggested that in addition to these risk factors, family structure and processes, such as the presence of depression and substance abuse in family members, were also linked to adolescent suicide behavior.5 In another study, Taliaferro and Muehlenkamp (2014) revealed that hopelessness and depressive symptoms were important risk factors that distinguished youth who reported suicidal ideation and those without, while self-injury differentiated those who attempted suicide from those who had suicidal ideation but without the attempt.4

In addition, past researchers have also found an association between bullying and suicide-related behavior in youth.7-9 For example, Hertz, et al (2013), suggested that the association between bullying and suicide-related behaviors was mediated by depression and delinquency in youth.7 Vergara, et al (2019), examined the different consequences in peer victimization and bully perpetration in suicide behavior. They found that bully perpetration was associated with the number of past month suicide attempts, while peer victimization was associated more with suicidal ideation.9

Aside from these risk factors, past studies have found the association between race and suicide.10-13 According to the 2017 data from National Center of Health Statistics, the age-adjusted suicide rates were highest for American Indians/Alaska Natives and Whites, compared to Hispanics, Asians/Pacific Islanders, or Blacks.12 Hawai‘i consists of diverse populations of Native Hawaiians, other Pacific Islanders, and multiple Asian groups (eg, Japanese, Filipinos, and other Asians) that are not commonly reported in the scientific literature. According to the 2018 American Community Survey, there were approximately 1.4 million persons living in Hawai‘i with 37.6% classified as Asian, 24.3% as White, 10.2% as Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders, and 24.3% as 2 or more races.14 A study by Wong, et al (2012), using Hawai‘i data from the 1999-2009 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys (YRBS) revealed a higher prevalence of Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, multiracial, and American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents in suicide-related behaviors (ie, suicide ideation, planning, and attempts), compared to Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White youth.10

Another study conducted by Hishinuma, et al (2018), examined longitudinal prediction of suicide attempts for Native Hawaiians, Peoples of the Pacific, and Asian Americans, and found that past suicide attempts being the strongest predictor for future suicide attempts for these race groups.6 This suggests that suicide-related behaviors occurred more frequently in some racial groups than others in Hawai‘i; that certain risk factors might be stronger for certain race groups; and that culturally-embedded approaches to suicide prevention might be necessary.15 Thus, the present study aims to determine the risk factors for adolescent suicide attempts in Hawai‘i using YRBS data from 2015-2017 and to examine the associations between adolescent suicide attempts with racial groups and other selected demographic characteristics.

Methods

Aggregate data from the 2015-2017 high school Hawai‘i YRBS were used for this study. The 2019 YRBS data were not available yet at the time of analyses. Developed in 1990, the YRBS is a national school-based survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to collect information on behaviors that put youth at risk for negative health outcomes, including substance use, unhealthy dietary behaviors, inadequate physical activity, sexual behaviors related to unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease, and behaviors that contribute to unintentional injuries and violence. Data are collected every odd year from Grade 9th through 12th students in public, non-charter schools in the US.

In this study, a total of 12 120 public high school respondents were analyzed from the 2015-2017 YRBS data. Suicide attempts were defined by those who reported having attempted suicide at least once in the past 12 months. There were 1 822 youth (15.0%) who did not respond to this question and were excluded from the analyses, resulting in a total of 10 298 participants. Depressive symptoms were defined by those who reported feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more during the past 12 months. Self-harm was classified into none, one-time, or repeatedly (≥ 2 times) of purposely hurting oneself during the past 12 months.

Unlike the national survey that combines all Asians into one category and aggregates Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander as a single race group,16 the Hawai‘i YRBS disaggregates these groups with the following race classifications based on the question in the survey, “Which one of these groups best describes you?”: White, Native Hawaiian, Japanese, Filipino, other Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino, other race, or “I do not describe myself as only one race or ethnicity.” Other covariates included bullying, which was defined by those who reported having been bullied on school property during the past 12 months. Illicit drug use was defined by those who had used any of the following at least once during the past 30 days: marijuana, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, ecstasy, prescription drugs (without doctor’s prescription), or hallucinogen. Alcohol use was defined by those who had at least one drink of alcohol at least once during the past 30 days.

Prevalence estimates of selected sociodemographic data and other characteristics by suicide attempts were obtained. Multivariate logistic regression modeling for complex survey procedure was created, using predicted marginals to estimate crude and adjusted prevalence ratios for suicide attempts. The model controlled for race, depressive symptoms, self-harm, bullying, illicit drug use, and alcohol use. Testing for interaction between race and depressive symptoms was identified (P < .01) with subsequent calculation of prevalence ratios for main effects. The final model included a total of 9 243 participants after listwise deletion of missing values in the independent and outcome variables. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, INC., Cary, NC) with a P -value of < .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 reports that the largest racial group represented in the 2015-2017 Hawai‘i YRBS data was Filipino (29.8%), followed by White (15.1%), Native Hawaiian (12.6%), and Japanese (12.2%). There was 18.7% of youth who reported “do not describe as only one race/ethnicity.” Approximately 10.2% of youth reported having attempted suicide at least once in the past 12 months. Estimates of suicide attempts were highest among youth who are Native Hawaiian, Hispanic/Latino, other Pacific Islander, those who do not describe as only one race/ethnicity, those who had repeated self-harm, those who experienced bullying, and those who used illicit drugs or alcohol (Table 2).

Table 1.

Selected Sociodemographic Characteristics of Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) Study Sample, Hawai‘i, 2015 to 2017 (N=12 120)

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Frequency | Weighted Percentage | 95% CIa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide Attempt | |||

| No | 9113 | 89.8 | 88.7-90.8 |

| Yes | 1185 | 10.2 | 9.2-11.3 |

| Missing | 1822 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1324 | 15.1 | 11.7-18.5 |

| Native Hawaiian | 1818 | 12.6 | 10.0-15.2 |

| Filipino | 2728 | 29.8 | 26.4-33.2 |

| Japanese | 1036 | 12.2 | 10.0-14.4 |

| Other Pacific Islander | 796 | 4.5 | 3.4-5.6 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 580 | 2.7 | 2.3-3.0 |

| Other Race | 632 | 4.4 | 3.3-5.5 |

| Do not describe as only one race/ethnicity |

2922 | 18.7 | 17.5-20.0 |

| Missing | 284 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | |||

| No | 8100 | 70.5 | 69.3-71.7 |

| Yes | 3630 | 29.5 | 28.3-30.7 |

| Missing | 390 | ||

| Bullying | |||

| No | 9458 | 81.5 | 80.4-82.6 |

| Yes | 2262 | 18.5 | 17.4-19.6 |

| Missing | 400 | ||

| Illicit Drug Use | |||

| No | 9839 | 82.7 | 81.2-84.2 |

| Yes | 2281 | 17.3 | 15.8-18.8 |

| Missing | 0 | ||

| Alcohol Use | |||

| No | 8167 | 75.2 | 73.6-76.7 |

| Yes | 3086 | 24.8 | 23.3-26.4 |

| Missing | 867 | ||

| Self-Harm | |||

| None | 9292 | 79.0 | 77.7-80.2 |

| One-time | 1082 | 9.1 | 8.2-10.1 |

| Repeatedly (≥2 times) | 1536 | 11.9 | 11.0-12.8 |

| Missing | 210 | ||

Note: Individual subgroup column totals may not sum to overall total due to missing/unknown data and row percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding. Also note that the time period for alcohol use and illicit drug use (past 30 days) is different from the time period for suicide attempt, depressive symptoms, bullying, and self-harm (past 12 months).

CI = confidence interval.

Table 2.

Selected Sociodemographic Characteristics for Respondents Who Had Attempted suicide at Least Once in the Past 12 Months, Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), Hawai‘i, 2015 to 2017

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Prevalence (%) | 95% CIa |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 7.6 | 5.8-9.3 |

| Native Hawaiian | 16.5 | 14.1-18.9 |

| Filipino | 8.8 | 7.1-10.4 |

| Japanese | 6 | 3.9-8.2 |

| Other Pacific Islander | 14.7 | 10.8-18.6 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 16.5 | 10.3-22.7 |

| Other Race | 9.8 | 5.9-13.8 |

| Do not describe as only one race/ethnicity |

10.9 | 9.3-12.5 |

| Depressive Symptoms | ||

| No | 4.5 | 3.7-5.4 |

| Yes | 20.3 | 18.7-22.0 |

| Bullying | ||

| No | 6.5 | 5.6-7.3 |

| Yes | 21.8 | 19.5-24.0 |

| Illicit Drug Use | ||

| No | 6.3 | 5.5-7.1 |

| Yes | 31.1 | 27.6-34.7 |

| Alcohol Use | ||

| No | 5.7 | 5.0-6.4 |

| Yes | 19.5 | 16.3-22.7 |

| Self-Harm | ||

| None | 4.1 | 3.5-4.6 |

| One-time | 22.1 | 16.9-27.3 |

| Repeatedly (≥2 times) | 41 | 37.1-44.9 |

Note: The time period for alcohol use and illicit drug use (past 30 days) is different from the time period for suicide attempt, depressive symptoms, bullying, and self-harm (past 12 months).

CI = confidence interval.

After adjusting for race, depressive symptoms, bullying, illicit drug use, alcohol use, and self-harm, youth who experienced bullying were more likely to have suicide attempts compared to those who did not experience bullying (adjusted prevalence ratio [APR]=1.75, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.44-2.12; Table 3a). Those who used illicit drugs (APR=1.89, 95% CI: 1.54-2.31) were more likely to have suicide attempts compared to those who did not use illicit drugs. Adolescents with one-time self-harm (APR=2.87, 95% CI: 2.04-4.04) or repeated self-harm (APR=5.31, 95% CI: 4.28-6.60) were more likely to have suicide attempts compared to those without any self-harm.

Table 3a.

Crude and Adjusted Prevalence Ratios (PR) of Bullying, Illicit Drug Use, Alcohol Use, and Self-harm, Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), Hawai‘i, 2015 to 2017

| Characteristics | Crude PR | 95% CIa | Adjusted PRb | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying | ||||

| No | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 3.37 | 2.83-4.01 | 1.75 | 1.44-2.12 |

| Illicit Drug Use | ||||

| No | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 4.94 | 4.27-5.70 | 1.89 | 1.54-2.31 |

| Alcohol Use | ||||

| No | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 3.43 | 2.70-4.36 | 1.31 | 1.00-1.71 |

| Self-Harm | ||||

| None | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| One-time | 5.46 | 4.17-7.14 | 2.87 | 2.04-4.04 |

| Repeatedly (≥2 times) | 10.11 | 8.69-11.77 | 5.31 | 4.28-6.60 |

Note: The time period for alcohol use and illicit drug use (past 30 days) is different from the time period for bullying and self-harm (past 12 months).

CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, depressive symptoms, bullying, illicit drug use, alcohol use, and self-harm.

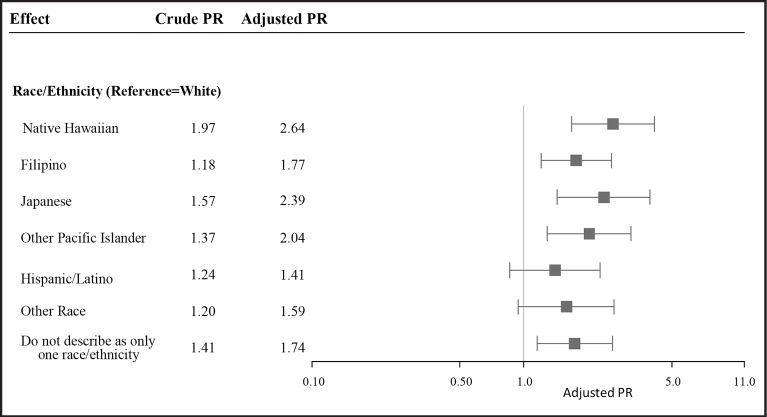

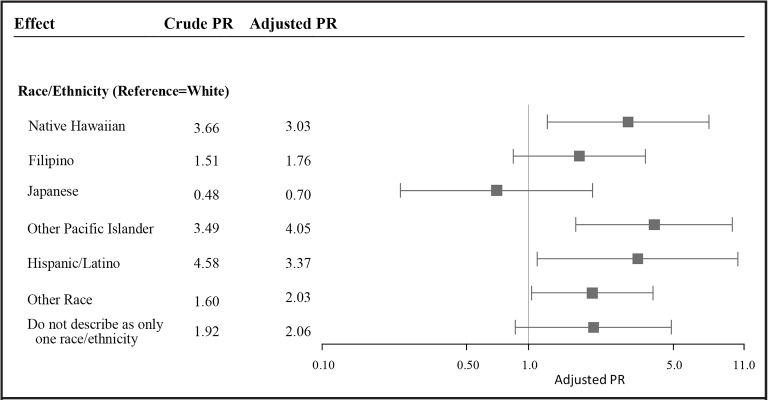

The effects of race on suicide attempts associated with the presence of depressive symptoms were explored, and the stratum-specific adjusted prevalence ratios were obtained (Table 3b). In the adjusted model when depressive symptoms were present (Figure 1), youth who are Native Hawaiian (APR=2.64, 95% CI: 1.68-4.15), Japanese (APR=2.39, 95% CI: 1.44-3.95), other Pacific Islander (APR=2.04, 95% CI: 1.29-3.21), Filipino (APR=1.77, 95% CI: 1.21-2.59), and those who do not describe as only one race/ethnicity (APR=1.74, 95% CI: 1.16-2.62) were more likely to have suicide attempts compared to White youth. On the other hand, when depressive symptoms were not present (Figure 2), other Pacific Islanders (APR=4.05, 95% CI: 1.69-9.67), Hispanics/Latinos (APR=3.37, 95% CI: 1.10-10.30), Native Hawaiians (APR=3.03, 95% CI: 1.23-7.45), and other races (APR=2.03, 95% CI: 1.03-4.00) were more likely to have suicide attempts compared to Whites.

Table 3b.

Crude and Adjusted Prevalence Ratios (PR) of Race/Ethnicity, Stratified by Depressive Symptoms

| Race/Ethnicity and Depressive Symptoms | Crude PR | 95% CIa | Adjusted PRb | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depressive Symptoms | ||||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Native Hawaiian | 3.66 | 1.39-9.60 | 3.03 | 1.23-7.45 |

| Filipino | 1.51 | 0.74-3.07 | 1.76 | 0.84-3.67 |

| Japanese | 0.48 | 0.18-1.32 | 0.7 | 0.24-2.03 |

| Other Pacific Islander |

3.49 | 1.67-7.29 | 4.05 | 1.69-9.67 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4.58 | 1.25-16.81 | 3.37 | 1.10-10.30 |

| Other Race | 1.6 | 0.77-3.33 | 2.03 | 1.03-4.00 |

| Do not describe as only one race/ ethnicity |

1.92 | 0.86-4.29 | 2.06 | 0.86-4.90 |

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Native Hawaiian | 1.97 | 1.37-2.83 | 2.64 | 1.68-4.15 |

| Filipino | 1.18 | 0.80-1.75 | 1.77 | 1.21-2.59 |

| Japanese | 1.57 | 0.93-2.65 | 2.39 | 1.44-3.95 |

| Other Pacific Islander |

1.37 | 0.92-2.04 | 2.04 | 1.29-3.21 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.24 | 0.76-2.03 | 1.41 | 0.86-2.29 |

| Other Race | 1.2 | 0.73-1.95 | 1.59 | 0.94-2.67 |

| Do not describe as only one race/ ethnicity |

1.41 | 0.94-2.12 | 1.74 | 1.16-2.62 |

Note: Interaction between race and depressive symptoms was significant, P <.01

CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, depressive symptoms, bullying, illicit drug use, alcohol use, and self-harm.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) for suicide attempt by race/ethnicity when depressive symptoms were present. Adjusted prevalence ratio adjusts for race/ethnicity, depressive symptoms, bullying, illicit drug use, alcohol use, and self-harm. The plot displays the adjusted prevalence ratio with 95% confidence intervals. The vertical line represents a prevalence ratio of 1.0, where there is no effect.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) for suicide attempt by race/ethnicity when depressive symptoms were not present. Adjusted prevalence ratio adjusts for race/ethnicity, depressive symptoms, bullying, illicit drug use, alcohol use, and self-harm. The plot displays the adjusted prevalence ratio with 95% confidence intervals. The vertical line represents a prevalence ratio of 1.0, where there is no effect.

Discussion

The study examined the risk factors for suicide attempts for adolescents in Hawai‘i and revealed that approximately 10.2% of youth reported having attempted suicide at least once in the past 12 months. This study highlighted the heterogeneity in the suicide attempt outcomes among different racial groups by depression symptoms.

Hawai‘i consists of diverse populations of Native Hawaiians, other Pacific Islanders, and multiple Asian groups. This study revealed higher estimates of suicide attempts for certain race groups including Native Hawaiians, other Pacific Islanders, Filipinos, and Hispanics/Latinos, compared to Whites. Consistent with past literature where depression was a significant risk factor,4,5 this study demonstrated a higher estimate of suicide attempts for youth with depressive symptoms.

This study reported a significant interaction between race and depressive symptoms, demonstrating the heterogeneity of the stratum-specific measures of association. The final adjusted model showed that when stratified by the presence of depressive symptoms, the effect of race on suicide attempt outcomes differed by whether depressive symptoms were present or not. When depressive symptoms were present, youth who are Native Hawaiian, Filipino, Japanese, other Pacific Islander, and those who do not describe as only one race/ethnicity were significantly more likely to have had suicide attempts compared to White youth. However, when depressive symptoms were not present, Native Hawaiians, other Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics/Latinos had a higher prevalence in suicide attempts compared to Whites, whereas Filipinos, Japanese, and those who do not describe as only one race/ethnicity did not differ from Whites in the prevalence of suicide attempts. It seems that race had a higher impact on suicide attempt outcomes when depressive symptoms were present.

The differential impact of race on suicide attempt outcomes might be related to the higher estimates of suicide attempts for certain race groups, particularly with Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders, who had higher prevalence for suicide attempts compared to Whites regardless of whether depressive symptoms were present or not. This is consistent with past research where Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native and multiracial adolescents were found to have increased risk for substance use, depression, and suicide.10,17-19 For example, Subica, et al (2018), conducted analyses using data from 1991-2015 Combined National Youth Behavioral Risk Surveys and found that Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander had a higher prevalence for depressed moods, suicide ideation, planning, and attempts compared to non-Hispanic White adolescents.18 Harder, et al (2012), reported that suicide was most prominent among indigenous youth as individuals suffered from acculturation and oppression, resulting in fragmentation and dislocation of culture that might negatively influence a person’s identity and self-esteem.19 The authors emphasized culture as an important protective factor against indigenous youth suicide. Thus, the present study showed variation in the prevalence of suicide attempts among several of the Asian and Pacific Islander racial groups that are typically aggregated together in national studies, suggesting the importance of evaluating specific subgroups when possible.

In this study, other Pacific Islanders reported the highest prevalence in adolescent suicide attempts compared to other race groups when depressive symptoms were not present. This is consistent with past research that adolescent suicide rates in the Pacific Islands were among the highest in the world.20-22 However, there is a lack of recent literature on adolescent suicide studying the Pacific Islander populations alone. When they were included in studies, these populations were often combined with other race groups into one aggregated group, making it difficult to draw conclusions based on this population alone.23

This study demonstrated that when depressive symptoms were present, there was a higher prevalence of suicide attempts among those who do not describe as only one race/ethnicity when compared to Whites. It is possible these youth with multiracial identities struggled with integrating their diverse racial identities, due to the person’s perception that the multiple racial identities were distinct and in conflict with one another,24 resulting in perceived racial discrimination and poor mental health outcomes.25,26 However, due to the limited information provided in the YRBS survey, it is not clear in this study how the prevalence of suicide attempts in this group differed from the group who were multiracial but identified as a single race.

Our study revealed that adolescents who experienced bullying, those who used illicit drugs, or those who had harmed themselves were more likely to have suicide attempts, compared to those who did not experience bullying, did not use illicit drugs, or did not harm themselves. The strongest predictor for suicide attempt was self-harm. An incremental, upward trend was found for self-harm, with youth who had hurt themselves repeatedly about 5 times more likely to have attempted suicide compared to those without self-harm. This is consistent with past research that indicated non-suicidal self-injury as a significant predictor for subsequent suicidal thoughts/behaviors.27 This study provides valuable information of the impact of self-harm on suicide attempts and highlights the need of screening adolescents for self-harm.

To improve the health and well-being of adolescents in Hawai‘i, it will be important to develop youth-centered, cultural approaches to suicide prevention, requiring the commitment of indigenous communities. Strength-based approach interventions with emphasis on individual abilities and mastery skills and relationships within family and community might serve as protective factors against suicide. In 2016, The Hawai‘i State Legislature passed a House Concurrent Resolution (HCR66) that mandated the formation of a Prevent Suicide Hawaii Taskforce (PSHTF) subcommittee to develop a strategic plan to reduce suicides in Hawai‘i by 25% by 2025. The PSHTF (https://health.hawaii.gov/injuryprevention/home/suicide-prevention/information/) is a state, public, and private collaboration of individuals, organizations, and community groups working together to set goals and develop strategies in suicide prevention. For example, the PSHTF held a 2-day, statewide conference in April 2019 that brought together policymakers, health professionals, survivors, and service providers who presented a wide variety of topics in suicide prevention, aiming at increasing awareness and enhancing coping skills for those at risk for suicide. In addition, the Hawai‘i Caring Communities Initiative (HCCI; http://blog.hawaii.edu/hcci/about/) for Youth Suicide Prevention implemented 2 strategic projects aiming at preventing youth suicide and increasing early identification and intervention of youth at risk. The HCCI used an evidence-based, youth-leadership approach to develop health promotion and community awareness activities in suicide prevention.28 Aside from these resources, Goebert, et al, provided in their study a list of available resources for suicide prevention in Hawai‘i.29

There are limitations of this study and caution is necessary for the interpretation and application of the results. First, the YRBS data were based on self-reported questions about suicide attempts, depressive symptoms, and self-harm. Response bias, ranging from simply misunderstanding the question to social desirability bias, often exist in self-reported data.30 As a result, the extent of underreporting or overreporting of these behaviors could not be determined. Also, the risk factors identified in this study were limited to those that were collected in the YRBS survey. Other risk factors identified by past researchers, such as depression or substance abuse in family members, were not collected in the survey, and could not be identified as risk factors in this study. In addition, the YRBS data applied only to youths who attended public, non-charter schools. Youth from charter and private schools were not included in the study and therefore, the sample was not representative of all persons in this age group. Students who were absent on the day the survey was administered were not included in the results, and thus, students with poorer health, higher absenteeism, and lower grades may be excluded. Finally, race categorization in this study was based on the question in the survey, “Which one of these groups best describes you?” which was limited to the single race category and provided limited race groupings. Although the survey provided the response option, “I do not describe myself as only one race or ethnicity,” information on multiracial category was limited and might result in the underrepresentation of certain race groups such as Native Hawaiian.

Suicide has a devastating impact on families, friends, and communities. Identifying groups at increased risk through available data may help inform public health programs in the development of targeted outreach with aims to reduce adolescent suicide attempts and improve the overall mental health of youth in Hawai‘i. Public health professionals who work with adolescents are encouraged to screen for depressive symptoms and self-harm and provide appropriate follow up that may help reduce the rate of adolescent suicide attempts in Hawai‘i. Increasing awareness of disparities in suicide attempts among the Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander race groups, those who experience depression symptoms, and those who had harmed themselves, would be crucial to help reduce the occurrence of suicide attempts in adolescents.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Hawai‘i State Department of Health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Hawai‘i State Department of Education for collecting data on the YRBS study. We would also like to thank the Hawai‘i Health Data Warehouse for providing the data and reviewing the manuscript.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- APR

Adjusted prevalence ratios

- CI

Confidence Interval

- YRBS

Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Heron M. Leading causes for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68((6)):1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtin SC, Heron M. Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2017. NCHS Data Brief. 2019;352:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Suicide in Children and Teens. Updated June 2018. Accessed August 10, 2020. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Teen-Suicide-010.aspx.

- 4.Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ. Risk and protective factors that distinguish adolescents who attempt suicide from those who only consider suicide in the past year. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44((1)):6–22. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilsen J. Suicide and youth: Risk factors. Front in Psychiatry. 2018;9((540)):1–5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hishinuma ES, Smith MD, McCarthy K, et al. Longitudinal prediction of suicide attempts for a diverse adolescent sample of Native Hawaiians, Pacific Peoples, and Asian Americans. Arch Suicide Res. 2018;22((1)):22. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2016.1275992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hertz MF, Donato I, Wright J. Bullying and suicide: a public health approach. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53((1)):S1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borowsky IW, Taliaferro LA, McMorris BJ. Suicidal thinking and behavior among youth involved in verbal and social bullying: Risk and protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:S4–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vergara GA, Stewart JG, Cosby EA, Lincoln SH, Auerbach RP. Non-Suicidal self-injury and suicide in depressed adolescents: Impact of peer victimization and bullying. J of Affect Disord. 2019;245:744–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong SS, Sugimoto-Matsuda JJ, Chang JY, Hishinuma ES. Ethnic differences in risk factors for suicide among American high school students, 2009: the vulnerability of multiracial and Pacific Islander adolescents. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16((2)):159–173. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2012.667334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute of Mental Health Suicide. Accessed August 17, 2020. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml.

- 12.Curtin SC, Hedegaard H. Suicide rates for females and males by race and ethnicity: United States, 1999 and 2017. NCHS Health E-Stat. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balis T, Postolache TT. Ethnic differences in adolescent suicide in the United States. Inter J Child Health Hum Dev. 2008;1((3)):281–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Census Bureau ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates:2018 ACS 1-Year Estimates Data Profiles. Accessed August 11, 2020. https://data.census.gov.

- 15.Goebert D, Alvarez A, Andrade NN, et al. Hope, help, and healing: Culturally embedded approaches to suicide prevention, intervention and postvention services with Native Hawaiian youth. Psychol Serv. 2018;15((3)):332–339. doi: 10.1037/ser0000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention YRBSS Data and Documentation. Updated June 9, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/data.htm.

- 17.Else IR, Andrade NN, Nahulu LB. Suicide and suicidal-related behaviors among indigenous Pacific Islanders in the United States. Death Studies. 2007;31((5)):479–501. doi: 10.1080/07481180701244595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subica AM, Wu LT. Substance use and suicide in Pacific Islander, American Indian, and multiracial youth. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54((6)):795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harder HG, Rash J, Holyk T, Jovel E, Harder K. Indigenous youth suicide: A systematic review of the literature. Pimatisiwin. 2012;10((1)):125–140. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin H. Study: Pacific youth more at risk of suicide than any other group. April 28, 2017. Accessed November 6, 2020. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/91938328/study-pacific-youth-more-at-risk-of-suicide-than-any-other-group.

- 21.Wilson C. Youth Suicides Sound Alarm Across the Pacific. August 12, 2014. Accessed November 6, 2020. http://www.ipsnews.net/2014/08/youth-suicides-sound-alarm-across.

- 22.Mathieua S, de Leoa D, Kooa YW, Leskea S, Goodfellowa B, Kõlves K. Suicide and suicide attempts in the Pacific Islands: A systematic literature review. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;17:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyatt LC, Ung T, Park R, Kwon SC, Trinh-Shevrin C. Risk Factors of Suicide and Depression among Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Youth: A Systematic Literature Review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26((2 Suppl)):191–237. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng C, Lee F. Multiracial identity integration: Perceptions of conflict and distance among multiracial individuals. J Social Issues. 2009;65:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reid Marks L, Thurston IB, Kamody RC, Schaeffer-Smith M. The role of multiracial identity integration in the relation between racial discrimination and depression in multiracial young adults. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2020;51((4)):317–324. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson KF, Yoo HC, Guevarra R, Jr, Harrington BA. Role of identity integration on the relationship between perceived racial discrimination and psychological adjustment of multiracial people. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59((2)):240–250. doi: 10.1037/a0027639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Eckenrode J, et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52((4)):486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung-Do JJ, Goebert DA, Bifulco K, et al. Hawai‘i’s Caring Communities Initiative: Mobilizing Rural and Ethnic Minority Communities for Youth Suicide Prevention. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2015;8((4)) Article 8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goebert D, Sugimoto-Matsuda J. Medical School Hotline: Advancing Suicide Prevention in Hawai’i. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76((11)):310–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenman R, Tennekoon V, Hill L. Measuring bias in self-reported data. Int J Behav Healthc Res. 2011;((4)):320–332. doi: 10.1504/IJBHR.2011.043414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]