Abstract

Background

With the emergence of SARS‐CoV‐2 in late 2019, governments worldwide implemented a multitude of non‐pharmaceutical interventions in order to control the spread of the virus. Most countries have implemented measures within the school setting in order to reopen schools or keep them open whilst aiming to contain the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2. For informed decision‐making on implementation, adaptation, or suspension of such measures, it is not only crucial to evaluate their effectiveness with regard to SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission, but also to assess their unintended consequences.

Objectives

To comprehensively identify and map the evidence on the unintended health and societal consequences of school‐based measures to prevent and control the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2. We aimed to generate a descriptive overview of the range of unintended (beneficial or harmful) consequences reported as well as the study designs that were employed to assess these outcomes. This review was designed to complement an existing Cochrane Review on the effectiveness of these measures by synthesising evidence on the implications of the broader system‐level implications of school measures beyond their effects on SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, four non‐health databases, and two COVID‐19 reference collections on 26 March 2021, together with reference checking, citation searching, and Google searches.

Selection criteria

We included quantitative (including mathematical modelling), qualitative, and mixed‐methods studies of any design that provided evidence on any unintended consequences of measures implemented in the school setting to contain the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Studies had to report on at least one unintended consequence, whether beneficial or harmful, of one or more relevant measures, as conceptualised in a logic model.

Data collection and analysis

We screened the titles/abstracts and subsequently full texts in duplicate, with any discrepancies between review authors resolved through discussion. One review author extracted data for all included studies, with a second review author reviewing the data extraction for accuracy. The evidence was summarised narratively and graphically across four prespecified intervention categories and six prespecified categories of unintended consequences; findings were described as deriving from quantitative, qualitative, or mixed‐method studies.

Main results

Eighteen studies met our inclusion criteria. Of these, 13 used quantitative methods (3 experimental/quasi‐experimental; 5 observational; 5 modelling); four used qualitative methods; and one used mixed methods. Studies looked at effects in different population groups, mainly in children and teachers. The identified interventions were assigned to four broad categories: 14 studies assessed measures to make contacts safer; four studies looked at measures to reduce contacts; six studies assessed surveillance and response measures; and one study examined multiple measures combined. Studies addressed a wide range of unintended consequences, most of them considered harmful. Eleven studies investigated educational consequences. Seven studies reported on psychosocial outcomes. Three studies each provided information on physical health and health behaviour outcomes beyond COVID‐19 and environmental consequences. Two studies reported on socio‐economic consequences, and no studies reported on equity and equality consequences.

Authors' conclusions

We identified a heterogeneous evidence base on unintended consequences of measures implemented in the school setting to prevent and control the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2, and summarised the available study data narratively and graphically. Primary research better focused on specific measures and various unintended outcomes is needed to fill knowledge gaps and give a broader picture of the diverse unintended consequences of school‐based measures before a more thorough evidence synthesis is warranted. The most notable lack of evidence we found was regarding psychosocial, equity, and equality outcomes. We also found a lack of research on interventions that aim to reduce the opportunity for contacts. Additionally, study investigators should provide sufficient data on contextual factors and demographics in order to ensure analyses of such are feasible, thus assisting stakeholders in making appropriate, informed decisions for their specific circumstances.

Keywords: Child, Humans, COVID-19, COVID-19/epidemiology, COVID-19/prevention & control, Pandemics, Pandemics/prevention & control, Quarantine, SARS-CoV-2, Schools

Plain language summary

Unintended consequences of school‐based measures to manage the COVID‐19 pandemic

Why is this question important?

Countries worldwide have taken many public health and social measures to prevent and control the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2, a highly contagious respiratory virus responsible for COVID‐19. A range of measures have been put in place to minimise transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 within schools and the wider community. Schools have the potential to be settings of high viral transmission because they involve extended interactions amongst people in close proximity. A previous review located and examined studies on the effectiveness of such school‐based measures regarding SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission. It is equally important to look at their unintended consequences on health and society in order that policymakers and parents can make informed decisions. Unintended consequences of a public health measure may be beneficial or harmful (or a mix of both). A public health measure may result in a mix of benefits and harms. For this review, we planned to examine the unintended consequences of measures designed to prevent and control the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 in schools. This review can therefore be seen as complementing the previous review on the effectiveness of such measures.

What did we do?

Firstly, we searched nine databases for studies that assessed any measure put in place in the school settings (primary or secondary schools, or both) to prevent transmission of the virus. We considered all types of studies and a broad range of outcomes.

Secondly, we grouped the identified studies according to the types of measures they examined. We then described which approaches were used in the studies, where these were conducted, and which unintended consequences were evaluated.

What did we find?

We found 18 studies that matched our inclusion criteria. Five studies used ‘real‐life’ data (observational studies); five studies used data generated by a computer and based on a set of assumptions (modelling studies); three studies were experimental studies (e.g. laboratory‐based); and four studies used qualitative methods, meaning they based their findings on interviews with people. One study used mixed methods, combining numerical and non‐numerical (qualitative) information.

Studies examined four different types of measures, as follows.

‐ Measures to reduce contacts (4 studies): policies to reduce the number of students in the school building (i.e. reducing the number of students present per class) and/or to reduce the number of contacts of students (e.g. through defined groups or staggered arrival, breaks, and departures).

‐ Measures to make contacts safer (14 studies): practices to ensure safer contacts between people in the school and classroom setting (e.g. mask mandates or distancing regulations), to modify the environment or activities (e.g. enhanced cleaning or ventilation practices).

‐ Surveillance and response measures to detect SARS‐CoV‐2 infections (6 studies): testing and/or screening strategies (e.g. temperature taking, screening tests for students and staff, and testing of symptomatic students and staff) and self‐isolation or quarantine measures.

‐ Multicomponent measures (1 study): interventions using a combination of at least two of the above measures.

We looked at the following unintended outcomes.

‐ Educational consequences (11 studies), e.g. changes in school performance, advancement to the next grade, or change in graduation numbers.

‐ Psychosocialoutcomes (7 studies), e.g. mental health, anxieties about going to school.

‐ Physical health and health behaviour outcomes beyond COVID‐19 (3 studies), e.g. hand eczema due to increased handwashing.

‐ Environmental consequences (3 studies), e.g. changes in air quality in classrooms.

‐ Socio‐economic consequences (2 studies), e.g. economic burden on families.

What did we conclude?

We identified a wide range of unintended consequences of school‐based measures designed to prevent the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2. However, the evidence base is small, and there are large gaps where more research is needed. This scoping review is a first step in gauging the extent of those consequences. More research is needed to collect additional information and to enable a more thorough analysis of the evidence. Psychosocial consequences (e.g. mental health issues, depression, loneliness) and equity and equality consequences (e.g. disadvantages for children from low‐income households, unfair distribution of work between genders for parents, are in need of further attention. We recommend that future research look at interventions such as fixed groups, alternating physical presence at school and staggered arrival departure and break times, as well as testing and quarantine measures.

How up to date is this evidence?

The evidence is up to date to March 2021.

Background

Since its reported emergence in Wuhan in late 2019, SARS‐CoV‐2 – the virus that causes COVID‐19 – has spread around the world, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a pandemic on 11 March 2020 and to urge all countries to take appropriate action (WHO 2020a).

Most countries have since implemented a variety of non‐pharmaceutical interventions, now also referred to as public health and social measures (PHSM), in order to contain and/or control the emerging crisis (WHO 2020b). One of the earliest and most widespread actions taken by governments around the world was the closure of primary and secondary schools. Over the course of the pandemic so far, more than 190 countries have closed their schools completely or partially over an extended period of time, putting more than 1.6 billion students (or 80% of enrolled learners worldwide) out of their classrooms at the peak of school closures (UNESCO 2020). The closure of schools is highly disruptive, and the appropriateness of such measures has been hotly debated. Uncertainty remains about the effectiveness of school closures in terms of reducing SARS‐CoV‐2 community transmission (Walsh 2021). Children appear to be less susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection than adults, and to contribute fewer secondary infections than adults (RKI 2021; Viner 2021a; Viner 2021b), casting doubt on the overall benefit of keeping schools closed to prevent transmission in the wider community. Moreover, concerns have also been raised about the likely harmful effects of school closures on children and their families, school staff, and the wider community (Bonell 2020; Viner 2021a; Viner 2021b).

In light of these concerns, academic and policy attention has shifted to the challenge of safely opening and operating schools amidst ongoing community transmission. To this end, governments have, to varying extents, implemented measures such as reduced class sizes, cohorting children in fixed groups and rotating systems, mandatory mask wearing inside the classroom and whilst travelling to and from school, symptom screening, and physical distancing (Couzin‐Frankel 2020; Dibner 2020). Research on these measures is being generated rapidly, but the evidence on their effectiveness remains equivocal. A recent Cochrane Review identified 38 observational and modelling studies assessing a variety of measures across three categories: reducing contacts, increasing the safety of contacts, and surveillance and response measures (Krishnaratne 2022). In some studies, these measures improved transmission‐related outcomes. However, some studies showed mixed results, and the certainty of the evidence was assessed as low or very low due to concerns about risk of bias of included studies and indirectness of the evidence (Krishnaratne 2022). Few studies in the review investigated the unintended consequences of school‐based measures, including adverse health effects and broader societal and systemic implications.

All PHSM influence outcomes beyond those they were designed to affect. Studying the unintended effects, including potentially harmful consequences of public health interventions, is essential to evaluating their overall impact and informing judgements about whether, when, and how they should be implemented (Bonell 2015; Rehfuess 2019). Unintended effects include the unanticipated consequences discussed in Merton 1936, as well as effects that may be predictable but nonetheless not part of an intervention’s intended causal chain or mechanism of action. Unintended consequences can be beneficial, harmful, or neutral (Turcotte‐Tremblay 2021).

Little is known as yet about the unintended consequences of school‐based measures intended to prevent, mitigate, or contain transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2. Several systematic reviews have studied the psychosocial consequences of lockdown and quarantine measures in children and adolescents (Fong 2020; Imran 2020; Panda 2021), whilst others have looked at children’s physical and mental health outcomes related to school closures (Viner 2021a; Viner 2021b). However, the likely much broader unintended effects on various aspects of society associated with school‐based measures remain unclear.

Objectives

Rationale for conducting a scoping review

A scoping review is a systematic (usually exploratory) approach to reviewing the research literature that can be used to determine the extent, variety, and characteristics of a body of evidence (Arksey 2005; Tricco 2018). Given the likely breadth and relative novelty of the topic of unintended consequences of school‐based measures during the COVID‐19 pandemic, we decided to conduct a scoping review in order to map the existing evidence in this area; to understand where evidence can be found; to examine what types of studies are available; and to identify gaps in the research base (Lockwood 2019).

Objectives of this scoping review

The main objective of this scoping review was to comprehensively identify and map the evidence on the unintended health and societal consequences of school‐based measures to prevent and control the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2. We aimed to generate a descriptive overview of the range of unintended (beneficial or harmful) consequences reported as well as the study designs that were employed to assess these outcomes. This review was designed to complement an existing Cochrane Review on the effectiveness of these measures (Krishnaratne 2022), by synthesising evidence on the implications of the broader system‐level implications of school measures beyond their effects on SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission.

Methods

The methods and inclusion criteria for this review were specified in advance in a protocol published on the Open Science Framework (osf.io/bsxh8/). We followed interim recommendations by the Cochrane Evidence Production & Methods Directorate, which were developed based on established methodologies (Lockwood 2019; Peters 2020; Tricco 2018). This review is reported in compliance with the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (Appendix 1) (Tricco 2018).

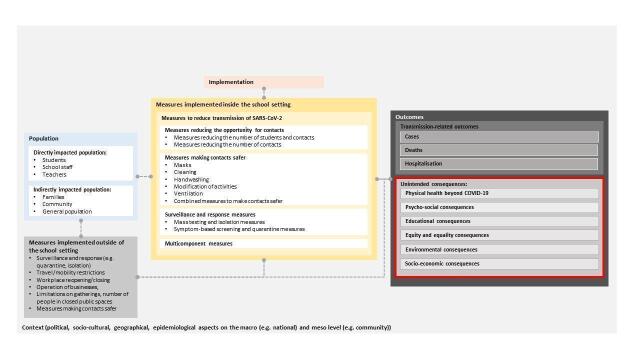

Logic model

This review was guided by a logic model that reflected our understanding of the school system (Figure 1), of the possible types of unintended consequences of measures implemented within the school and school system at the start of this scoping review. It was informed by a more comprehensive system‐based logic model developed previously for a published Cochrane scoping review (Krishnaratne 2020), and a published Cochrane Review on the effectiveness of these school‐based measures (Krishnaratne 2022). We adapted this system‐based logic model to focus on unintended consequences rather than intended outcomes of the measures, by (i) concentrating on the most directly relevant elements of the system‐based logic model (i.e. population, measures, outcomes); (ii) drawing on the WHO‐INTEGRATE framework, an evidence‐to‐decision framework that examines the implications of public health interventions from a system‐wide perspective (Rehfuess 2019); and (iii) a framework to anticipate and assess adverse and other unintended consequences of public health interventions (Bonell 2020). The resulting logic model of unintended consequences describes three types of school‐based measures and their manifold health and broader implications for those directly affected (students, teachers, school staff) (Figure 1), those indirectly affected within the local community (parents, families), and society at large. In categorising unintended consequences, we proceeded with greater granularity for consequences of particular relevance in the school setting (e.g. treating physical and psychosocial health as two separate categories, establishing a distinct 'educational consequences' category) than for consequences of lesser relevance in the school setting (e.g. environmental consequences). Whilst these a priori categories provided the basis for the initial sorting of findings extracted from included studies, we deliberately maintained an openness to identifying consequences potentially outside of these categories.

1.

Figure 1: Logic model of school‐based measures to prevent and control the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 and their unintended consequences. The logic model follows the PIO (population, intervention, outcomes) scheme. This logic model is based on the previously developed logic model for a Cochrane scoping review, Krishnaratne 2020, and a Cochrane Review on the effectiveness of school‐based measures (Krishnaratne 2022).

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of study

We included any study that assessed the impact of measures implemented in the school setting to contain the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic on any unintended consequences. This means multiple study types were eligible, including quantitative (including both empirical and mathematical modelling studies), qualitative, and mixed‐methods studies. This broad criterion is reflective of the objective of this scoping review, which is to comprehensively identify and map evidence on all potential unintended consequences. Studies had to report on at least one unintended consequence, whether beneficial or harmful, of one or more relevant measures, as conceptualised in a logic model.

Settings

To be included in this scoping review, and aligned with the existing intervention effectiveness review (Krishnaratne 2022), studies had to investigate interventions within the primary and/or secondary school setting. We considered a school to be any setting in which the main purpose is to provide education to children. For this review, we defined the setting ‘school’ as the school building; the school grounds; vehicles to arrive at, return from, or move around on or between school premises; or any setting related to any activity organised by or linked to the school. Measures implemented by or around the school may therefore affect any activity carried out on the school premises or on the way to school, including before, during, or after class or during breaks.

We excluded studies looking solely at kindergarten and/or preschool settings and university and college settings.

Populations

Similar to Krishnaratne 2022, we distinguished between three population groups. First, we examined the directly affected population inside the school, including students, teachers, and other staff, as well as the school as an organisation in itself. We also looked at the more indirectly affected population outside the school, where we further differentiated between the local community (i.e. parents or family of people directly affected, the second group), and society at large (the third group). Students could be between 4 and 18 years of age; studies with a subset of participants outside this age range (e.g. German schools, where some students may be 19 years old) were also included.

Interventions

We included studies that investigated any measures implemented in the school setting with the aim of preventing the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2. Informed by the published intervention effectiveness review (Krishnaratne 2022), we classified eligible interventions into four broad categories, as follows.

1. Measures to reduce contacts

Policies and practices to reduce the number of students in the school building, that is reopening school for certain class types or reducing the number of students present per class. Policies and practices to reduce the number of contacts of all students present onsite, that is through defined groups (i.e. cohorts) or staggered arrival, breaks, and departures.

2. Measures to make contacts safer

Policies and practices to ensure safer contacts between individuals in the school and classroom setting (e.g. mask mandates, distancing regulations, handwashing guidelines, respiratory etiquette); to modify the physical environment (e.g. enhanced cleaning or ventilation practices); or to modify activities (e.g. no contact sports in physical education class) and vaccination policies and practices.

3. Surveillance and response measures in relation to SARS‐CoV‐2 infections

Testing and/or screening strategies for individuals and/or groups (e.g. temperature taking, screening tests for students and staff, testing of symptomatic students and staff) and related self‐isolation or quarantine measures (e.g. stay‐at‐home‐orders for students or school staff with symptoms, or those who have had contact with infected individuals, or those who have had a positive test result).

4. Multicomponent measures

Interventions using a combination of at least two of the aforementioned measures.

We excluded studies if:

they described proactive school closures (e.g. complete school closures during a general lockdown) rather than measures implemented whilst schools were open or partially open;

they described COVID‐19‐related interventions implemented in settings other than the school setting (as defined above), for example general containment and mitigation measures (e.g. community‐based quarantine, personal protective measures, hygiene measures, bans on mass gatherings and other social‐distancing measures);

they described interventions aiming to mitigate the (negative) effects of a general lockdown and/or school closures and/or school measures (e.g. improvements to online‐learning platforms).

Outcomes

To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to report at least one unintended consequence, whether beneficial or harmful, of one or more of the relevant measures. Such unintended consequences may be predictable (e.g. considered during the planning stages of the intervention) or unexpected. Six categories of unintended consequences were prespecified in our logic model:

physical health and health behaviour outcomes (not associated with COVID‐19, e.g. health seeking behaviour);

educational consequences (impact on school performance);

psychosocial outcomes (impact on mental health or social well‐being);

consequences for equity and equality (impact on fair distribution of benefits and burdens between groups of populations or individuals);

environmental consequences (both within the school setting and the broader environment); and

socio‐economic consequences (at individual, family, and societal levels).

An unintended consequence did not have to fit our predefined categories; we were open to the emergence of other categories from the review itself. We excluded studies that reported only on intended SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission‐related outcomes or other infectious disease control‐related outcomes. Whether a consequence can be considered 'unintended' was judged by the review team, regardless of whether it had been explicitly labelled as such by the primary study authors.

Search methods for identification of studies

The search strategy consisted of both controlled vocabulary, such as the National Library of Medicine’s MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms, and keywords. The search was built around four main components, namely: 1) SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID‐19; 2) school settings; 3) control measures; and 4) unintended consequences. We combined results from two strategies, notably for searches of 1) SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID‐19 and 2) school settings and 3) control measures, and for searches of 1) SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID‐19 and 2) school settings and 3) unintended consequences. The starting date was limited to 1 January 2020, the point at which publications about schools and the COVID‐19 pandemic began to appear. No study design filters were applied to the search, as a wide range of study types were considered for inclusion.

An experienced Information Specialist (RF) designed and executed the searches, which were verified by a content expert and reviewed by a second Information Specialist.

We ran searches in the following electronic databases between 26 March and 30 March 2021:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 3); searched 26 March 2021 via the Cochrane Register of Studies (crsweb.cochrane.org);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 25 March 2021);

Embase Ovid (1974 to 25 March 2021);

Ovid APA PsycINFO (1806 to March Week 4 2021);

Ovid ERIC (1965 to January 2021);

Web of Science (Social Sciences Citation Index – 1900 to present, Science Citation Index Expanded – 1900 to present, and Emerging Sources Index – 2005 to present) via Clarivate;

Academic Search Complete via EBSCOhost (1887 to present).

We also searched the following COVID‐19‐specific databases:

Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register (covid-19.cochrane.org/) searched on 26 March 2021 via the Cochrane Register of Studies (crsweb.cochrane.org/);

WHO COVID‐19 Global literature on coronavirus disease (search.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/) searched on 30 March 2021.

To retrieve grey literature of unpublished reports or studies not published through traditional models, we conducted two Google web searches on 30 March 2021, and screened the first 10 pages of relevancy‐ranked results (200 web pages).

The full search strategy is presented in Appendix 2. Finally, we reviewed the cited and citing references of all relevant systematic reviews identified through the searches, as well as for all included studies (for a list of reviews used for this 'backward and forward' snowballing search, please see Appendix 3).

Language

Within our review team, we were able to accommodate studies written in Armenian, English, French, German, Italian, Russian, and Spanish. Where necessary, we asked for help with translation of other languages (e.g. Portuguese) using our networks. However, we mainly found English studies and one German study that met our inclusion criteria.

Study selection

We used EndNote X9 for de‐duplication and management of all records (EndNote). For title and abstract screening, we used Rayyan (Ouzzani 2016), a web‐based application designed for citation screening. We created guidance to ensure similar and consistent screening by all review authors. In a preliminary calibration exercise, all review authors involved in this step (BV, CK, JS, KW, RB, and SK) screened a randomly selected batch of 50 titles and abstracts. In a subsequent discussion, we addressed and resolved unclear cases and adjusted the guidance. All titles and abstracts were then screened in duplicate. Questions concerning any unclear studies could be posted in a rolling questions sheet available to all review authors. Any additional uncertainties and discrepancies were resolved through discussion, including with a third review author or in the wider team when necessary. At this stage only clearly irrelevant studies were excluded.

We followed similar steps during full‐text screening. All review authors involved in this step (AM, BV, CK, JR, JS, RB, and SK) screened the same batch of 10 studies for calibration. Within the team, we had a meeting to address open questions and revised the guidance. The full texts were screened in duplicate, with any disagreements resolved through discussion or, when necessary, through involvement of a third review author.

Final decisions regarding inclusion or exclusion were made, and reasons for excluding studies at the full‐text stage documented.

Data extraction and charting

Two review authors (SK, BV) piloted a standardised data extraction form with five included studies, including one qualitative, three quantitative (one modelling and two observational), and one mixed‐methods study, adapting the form where necessary. One review author (SK) then extracted study characteristics and data for all included studies, and a second review author (BV) checked the extraction. The information was extracted as reported by the study authors themselves in the original paper. All extraction categories and subcategories are shown in Appendix 4.

Collation, summary, and reporting of results

One review author (SK) collated, summarised, and reported the extracted data, which a second review author (BV) reviewed. We used the categories of intervention types (i.e. measures to reduce contacts, measures to make contacts safer, surveillance and response measures, multicomponent interventions); the predefined outcome categories (i.e. physical health and health behaviour outcomes, educational consequences, psychosocial outcomes, consequences for equity and equality, environmental consequences, and socio‐economic consequences); and study designs (i.e. quantitative, qualitative, and mixed‐methods studies) to summarise and present clusters of information. Whilst we were open to additional categories emerging during the analysis, all data fit the predefined categories. Firstly, we developed a broad overview of key characteristics of each included study in tabular form. We then collated the findings in the form of a graphical evidence map, in which each cell represents an intervention‐outcome pair reported in one of the included studies.

Results

Results of the search

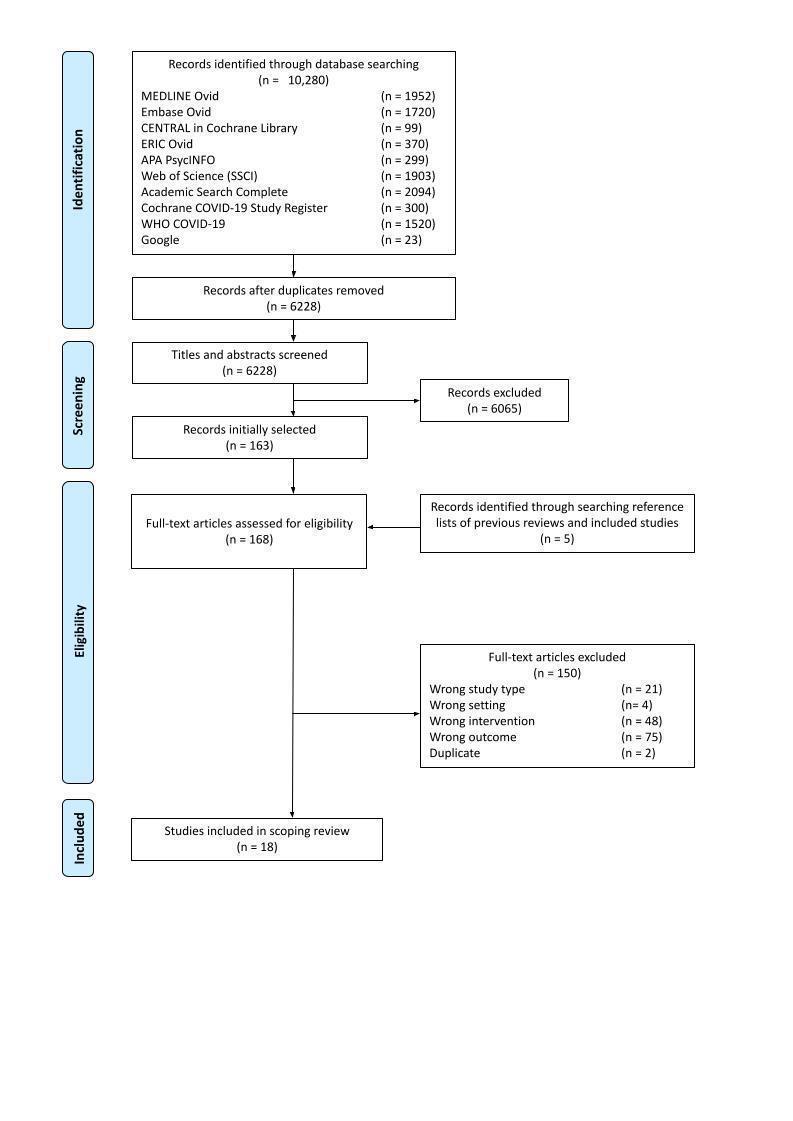

Our study screening process is summarised in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2). Our searches yielded 6228 records after de‐duplication. Following title and abstract screening, 163 articles were retained for assessment at the full‐text screening stage, of which 16 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. Citation searches of relevant reviews and included studies identified an additional five potentially relevant studies, two of which met our inclusion criteria. We included a total of 18 studies, of which 10 were peer‐reviewed journal articles, six were published on preprint servers, and two were think‐tank reports.

2.

PRISMA flow diagram.

We excluded 150 studies at the full‐text stage. A list of selected excluded studies that we considered likely to be of interest to readers (principally because they met most, but not all, of our inclusion criteria, and because deliberation over their eligibility prompted lengthy discussions amongst the review team during the screening process) can be found in Characteristics of excluded studies.

Description of studies

In this section we have provided an overview of the key characteristics of the included studies, based on study design as well as the population, setting, intervention, and outcome categories specified in the logic model. Seventeen of the 18 included studies were published in English, whilst one study was published in German (Steffens 2021). We identified a high degree of heterogeneity across studies. This overview demonstrates the broad range of topics covered by the included studies, especially concerning the intervention and outcome categories. See Characteristics of included studies.

Study type

The largest group of included studies (13 studies) was quantitative. Of these, observational, Borch 2020; Doron 2021; Li 2021; Schwarz 2021; Simonsen 2020, and modelling studies, Cohen 2020; Gill 2020b; Phillips 2021; Saad 2020; Steffens 2021, are represented with five studies each, whilst three studies used quasi‐experimental or experimental designs (Alonso 2021; Curtius 2021; Ruba 2020). Four studies drew on qualitative methods (Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Hortigüela‐Alcalá 2021; Lorenc 2021; Marchant 2020). One study employed a mixed‐methods design (Gill 2020a).

Population

Most studies assessed relevant outcomes in populations directly affected by school‐based measures. All but one study, Saad 2020, included at least one population group within the school system (students, teachers, or school staff). Of these, 10 studies reported relevant outcomes solely for students (Alonso 2021; Borch 2020; Cohen 2020; Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Gill 2020a; Gill 2020b; Phillips 2021; Ruba 2020; Schwarz 2021; Simonsen 2020); two for teachers only (Hortigüela‐Alcalá 2021; Li 2021); and five studies reported outcomes for both groups (Curtius 2021; Doron 2021; Lorenc 2021; Marchant 2020; Steffens 2021). No studies explicitly reported on school staff other than teachers. Of the 15 studies reporting outcomes in children, five did so through surveying or interviewing parents, teachers, or doctors, rather than the children themselves (Borch 2020; Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Gill 2020a; Schwarz 2021; Simonsen 2020). Three studies reported unintended outcomes in other populations, namely families or caregivers of school‐aged children (Doron 2021; Lorenc 2021; Saad 2020). One of these also reported outcomes for the society at large (Saad 2020).

Settings

The included studies were mainly set in Europe and North America, notably in the USA (6), Germany (3), Spain (2), Denmark (2), Canada (2), England (1), and Wales (1). Only one study from outside these two world regions (conducted in China) met our inclusion criteria.

Half of the included studies (n = 9) looked at both primary and secondary schools (two of which additionally assessed outcomes in preschool children, and another two that also documented outcomes in high school and university teachers). Four studies were concerned solely with primary school settings, whereas two studies focused on secondary school settings. In three studies, the school setting was not clearly specified. Two of these studies modelled hypothetical schools or classrooms without specifying the type of school.

Interventions

A wide variety of interventions were examined in the included studies, with many studies investigating several measures.

Consequences of interventions designed to reduce the opportunity for contacts within the school setting were reported in three qualitative studies and one modelling study. One study looked at a hybrid learning approach, with half the class learning on site and the other half online, which reduces the number of students in school and therefore the possibilities for contacts (Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021). In two other studies (Lorenc 2021; Marchant 2020), the opportunity for contacts was reduced through forming fixed cohorts whilst all students were present in school. In one study (Phillips 2021), the opportunity for contacts was reduced through halving the school day.

The majority of studies (n = 14) evaluated at least one measure to make contacts within the school setting safer, including mask wearing (Gill 2020a; Hortigüela‐Alcalá 2021; Li 2021; Ruba 2020; Schwarz 2021), improved hygiene measures (Borch 2020; Hortigüela‐Alcalá 2021; Marchant 2020; Simonsen 2020), ventilation protocols and air purifiers (Alonso 2021; Curtius 2021; Steffens 2021), distancing (Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Hortigüela‐Alcalá 2021; Lorenc 2021; Marchant 2020), and modified activities (Phillips 2021).

We identified six studies on surveillance and response measures. Of these, three studies looked at consequences of screening within the school (Doron 2021; Lorenc 2021; Saad 2020), and three evaluated response measures after a case was detected (Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Gill 2020b; Phillips 2021).

One study modelled the effects of several interventions (mask wearing, distancing, hand hygiene, cohorting, screening, quarantine) implemented together without differentiating between the effects of the individual interventions (Cohen 2020).

Outcomes

Eleven studies investigated educational consequences (Curtius 2021; Cohen 2020; Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Gill 2020a; Gill 2020b; Hortigüela‐Alcalá 2021; Lorenc 2021; Marchant 2020; Phillips 2021; Schwarz 2021; Steffens 2021); seven studies reported on psychosocial outcomes (Doron 2021; Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Li 2021; Lorenc 2021; Marchant 2020; Ruba 2020; Schwarz 2021); three studies provided information on physical health and health behaviour outcomes beyond COVID‐19 (Borch 2020; Schwarz 2021; Simonsen 2020); and three studies provided information on environmental consequences (Alonso 2021; Curtius 2021; Steffens 2021). Two studies examined socio‐economic consequences (Doron 2021; Saad 2020).

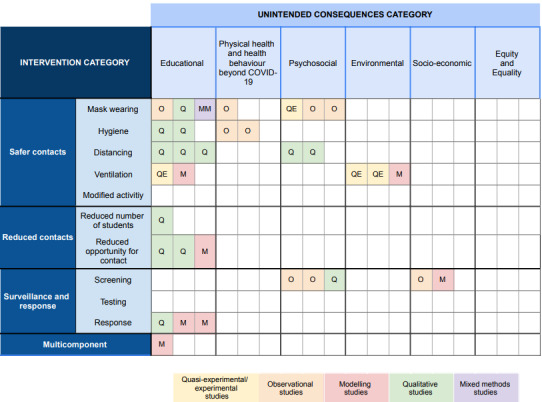

Evidence map and summary

The evidence map presented in Figure 3 gives a graphical overview of the interventions and unintended consequences examined in the included studies and the distribution of study approaches through which each intervention‐outcome pair was investigated.

3.

Evidence map of unintended consequences of school‐based measures to prevent SARS‐CoV‐2. Each square represents the case in which a single included study evaluated a type of school measure (rows) against an unintended consequences category (columns); additionally, the study type is provided (colour).

The largest group of identified unintended consequences by far was educational consequences. Within this category, the most studied interventions were measures to make contacts safer, mainly through qualitative methods. Studies described or predicted negative impacts on learning resulting from distancing and/or mask mandates during class, Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Lorenc 2021; Schwarz 2021, or the use of air purifiers, Curtius 2021; Steffens 2021, that may impair students' ability to hear the teachers and follow the class. Other studies assessed the impact on teachers and their capacity to provide support to their students. Teaching was found to be affected by being required to wear masks in class (Gill 2020a; Hortigüela‐Alcalá 2021); by having to implement extensive hygiene regulations (Hortigüela‐Alcalá 2021; Marchant 2020); and by complying with distancing measures (Hortigüela‐Alcalá 2021; Lorenc 2021). All four studies that looked at reducing contacts reported solely on consequences for the education of children. Two studies reported on disruptive learning or negative impacts on student behaviour, either due to reducing the number of students present at school (Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021), or to reduced contacts through fixed cohorts (Lorenc 2021), whilst one study looked at missed school days and missed time at school after halving a school day (Phillips 2021). Notably, only one study mentioned a positive educational consequence for students, namely the benefit of reduced ratios of students to teachers due to smaller, alternating cohorts (Marchant 2020). Within the surveillance and response category, three studies assessed educational consequences like learning continuity (Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021), or the number of missed school days (Gill 2020b; Phillips 2021), all of which were reported in relation to response measures, such as sending children home after showing symptoms or quarantining after close contact with an infected person.

Three studies reported physical health outcomes, all of which investigated the effects of safer contact measures using observational designs. These outcomes included the incidence of hand eczema or irritant contact dermatitis due to frequent handwashing (Borch 2020; Simonsen 2020), and various health outcomes such as headaches, skin reactions, and tiredness associated with mask wearing (Schwarz 2021).

The findings of psychosocial outcomes were highly heterogeneous, with outcomes mainly being reported for safer contact measures. Here, most studies described some form of reduced general well‐being, reduced level of comfort, or concerns or anxiety felt by children as well as teachers about attending school with measures like distancing, Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Marchant 2020, or mask wearing, Li 2021; Schwarz 2021, in place. One study assessed how mask wearing in class may impact children’s social interaction and their emotional inferences (i.e. their ability to read emotions from facial expressions) (Ruba 2020). We did not identify any study examining reduced contact measures with regard to psychosocial outcomes. In contrast, two studies linked asymptomatic screening, as part of surveillance and response measures, to psychosocial outcomes (Doron 2021; Lorenc 2021). Both studies reported on the stigma students or teachers might face when receiving a positive test at school, and one study documented an increased level of comfort after implementing weekly pooled polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests (Doron 2021).

Three studies of safer contact interventions looked at environmental consequences, such as increased noise levels and improved air quality within the classroom following the installation of mobile air purifiers (Curtius 2021; Steffens 2021), and changes in air quality due to changed ventilation schedules (Alonso 2021). Two studies assessed changes in thermal comfort, defined as the combination of temperature and potentially disturbing air circulation, as perceived by students and teachers, due to changed ventilation schedules (Alonso 2021; Curtius 2021).

We identified two outcomes in the socio‐economic category, both of which were connected to screening measures. One modelling study examined economic implications of daily random testing of students within a school by calculating the costs of increased healthcare seeking after the measure was implemented (Saad 2020). A second observational study identified the possible economic burden for the households of students quarantining after testing positive in weekly pooled PCR tests (Doron 2021).

The most obvious gap in the evidence map was a complete lack of studies reporting on consequences for equity and equality, for example how individuals or populations groups might be disadvantaged or discriminated against by the implementation of the measures (e.g. unfair distribution of work between genders for parents, higher burden for children with special needs). Very few outcomes were identified in the socio‐economic category as well as in the environmental consequences and physical health outcomes categories. Psychosocial outcomes and educational consequences, on the other hand, are well represented in our evidence base.

A second notable gap in the evidence includes research on the unintended outcomes of measures designed to work by reducing contacts. Only one unintended consequence was identified for measures designed to work by reducing the number of students in the school building (i.e. halving class sizes). Whilst three studies identified unintended consequences of measures that reduce the opportunity for contacts, none of these investigated common measures in this category like staggered arrival and departure times, or staggered break times for students and staff. Twenty‐three studies looking at the effectiveness of such contacts‐reducing measures were identified and evaluated in the previous effectiveness review (Krishnaratne 2022). Our searches on unintended consequences, however, did not yield many results.

Discussion

Summary of results

In this scoping review, we mapped the evidence on the unintended consequences of interventions implemented in and around schools to prevent the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2. We identified 18 studies across eight countries that provided evidence on at least one unintended consequence.

With the exception of a single Chinese study, all of the included studies were conducted either in Europe or North America, or investigated hypothetical school settings without reference to a particular country. Most studies did not mention context or implementation factors, which makes it hard to generalise the outcomes to other settings, since for example cultural or economic differences between countries and regions may influence whether a measure is effective and what unintended consequences it may show. Most studies focused on directly affected populations within schools – in particular students and teachers, whilst few addressed unintended consequences for indirectly affected populations, such as families, communities, and the society at large. The majority of studies were based on empirical (quantitative and/or qualitative) data, although five mathematical modelling studies were also identified.

The majority of the included studies examined educational consequences, whilst a large number also identified health‐related outcomes – both physical and psychosocial – amongst students and teachers. We did not identify any studies that focused on equity‐/equality‐related consequences, and socio‐economic consequences were examined by only a small set of studies. Reasons for this lack of evidence may be that these larger‐scale consequences may be harder to measure than consequences on individuals, or may only become visible and measurable with a bigger time difference to the intervention.

We found that unintended consequences of interventions designed to increase the safety of contacts within and around schools were more often assessed than interventions designed to reduce contacts, and surveillance and response measures.

Overall, the evidence base on the unintended consequences of school‐based measures to prevent the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 is thin. Whilst all 18 included studies contributed relevant data, and diverse unintended consequences were identified, we did not find evidence of a comprehensive or coherent body of research on these outcomes. Instead, we identified a patchwork of studies, many only tangentially related to our review question. In most of the included studies, unintended consequences constituted a relatively minor focus of the investigation, and we identified no studies with the specific aim of studying unintended consequences in general, or a specific category thereof. To our knowledge, there is no deliberate, systematic research effort to identify, quantify, and/or theorise the unintended consequences of school‐based SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID‐19 prevention measures.

Decisions about whether, how, and when to implement, scale‐up, or de‐implement COVID‐19 risk mitigation measures in school settings require an understanding of both of their likely effectiveness (i.e. their impact on SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission and COVID‐19 morbidity and mortality) and their potential unintended consequences, harmful as well as beneficial. Consequently, for a complete picture of the evidence base, education officials and other policymakers should consider the findings of the current review in conjunction with the recently published (and soon to be updated) Cochrane effectiveness review on school measures (Krishnaratne 2022). Krishnaratne 2022 reported that an array of measures implemented in the school setting during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic can have a positive impact on transmission and healthcare utilisation outcomes. However, this scoping review found that these measures may also lead to a broad range of unintended consequences. Further investigation of short‐ and long‐term consequences of school measures, intended or unintended, during the ongoing pandemic is warranted.

Strengths and limitations

Through the description of identified studies, the study designs employed, and the combination of interventions and outcomes investigated, this scoping review provides an initial overview of the research on the unintended consequences of measures implemented in the school setting to prevent the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 to date. It can therefore be understood as a complement to the Cochrane Review on the effectiveness of measures implemented in schools during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Krishnaratne 2022).

Authors of the published Cochrane effectiveness review noticed that very few outcomes besides transmission or healthcare utilisation were identified (Krishnaratne 2022), and the main body of evidence in this review consisted of mathematical modelling studies, which by design make it hard to evaluate unintended consequences. In this scoping review, we included quantitative evidence, which, through its explorative character, may be better suited to assess unintended consequences.

This review was conducted according to a strict and thorough methodology developed by the Cochrane Network. Our electronic search strategies were comprehensive, covering a wide range of databases across multiple academic fields and disciplines, and were supplemented by forward and backward citation tracking, both of included studies and relevant published reviews. Our database searches were designed with the support of, and were run by, an information retrieval specialist.

Detailed standardised instructions for the conduct of each stage of the review were developed and provided to the review team members, and the team met regularly to discuss queries and to resolve uncertainties and concerns. Planned procedures for each stage of the review were piloted and fine‐tuned through calibration exercises. All decisions related to study screening and selection and data extraction were either performed in duplicate, or double‐checked as a safeguard against the influence of bias and human error, and to maximise consistency.

Despite these strengths, we encountered some challenges whilst attempting to meaningfully collate and integrate this highly multifarious literature. Most significantly, it was not always straightforward to determine what can be considered an unintended consequence. For example, several studies reported on the number of school days lost as a result of a measure or measures (Cohen 2020; Gill 2020a; Gill 2020b; Phillips 2021), but only in some cases did we interpret this as an unintended consequence. In other studies – most notably studies of measures that involved splitting students into cohorts or pods and alternating their school attendance – we determined that lost school days were part and parcel of the intervention rather than an unintended effect. In arriving at such judgements, we made a firm distinction between, on the one hand, those consequences that are likely to logically fall on the hypothesised causal chain of a measure, intermediate to intervention inputs/activities and its predicted impacts on COVID‐19‐related outcomes, and, on the other hand, outcomes that are likely to be genuinely unintended. Our a priori logic model was very helpful in these processes of conceptualisation. We have tried to be very open and flexible in the definition of unintended consequences; it is worth noting that future research may identify unintended consequences that were not predicted with our logic model, and our flexible search approach allowed for this.

Similarly, in some cases, a great deal of judgement was involved in determining whether reported unintended consequences could actually be reasonably linked to the interventions in which we were interested. This was at times attributable, in part, to a lack of detailed reporting in the included studies. In some cases (Fontenelle‐Tereshchuk 2021; Gill 2020a; Gill 2020b; Lorenc 2021), the reported unintended outcomes were (partially) derived from qualitative data about the anticipated (i.e. not actual) adverse effects of social distancing on schoolchildren, presenting us with the challenge of determining whether such findings were sufficient to warrant inclusion. After discussions within the team we decided to take an inclusive posture, determining that participant perceptions of anticipated or likely unintended consequences, or both, were within the scope of our review focus and would be of value to report. Still, these were subjective judgements, and it is possible that a different review team would have come to slightly different conclusions.

This scoping review was designed and conducted, and the results were written up, amidst a rapidly evolving global public health emergency. Research on COVID‐19 is being generated at a pace unprecedented in the history of academic public health (Palayew 2020). Whilst we planned, conducted, and wrote this review rapidly, it is likely that relevant studies have been published during the time period between the conduct of our searches and the publication of this paper. The results of this review represent the evidence available in March 2021; the universe of intervention types and unintended outcomes for which evidence is now available has no doubt expanded during the past year. Important developments in the pandemic over the course of 2021 – the emergence of new variants of concern, the widespread availability of vaccines (in some contexts), and, most importantly, evolution in how governments are approaching COVID‐19 mitigation in their jurisdictions – have changed the contexts in which decisions about school‐based interventions are made. Decision‐makers must therefore take into consideration the current pandemic situation when applying these results in their contexts.

Authors' conclusions

With this scoping review, we were able to gain an initial understanding of the potential unintended consequences of measures implemented in and around schools to contain the spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 in this setting. The 18 included studies covered a heterogeneous range of unintended consequences; nevertheless, we identified wide gaps in the evidence base.

More targeted primary research is needed to fill the identified gaps in the evidence base in order to gain the full picture of consequences related to measures implemented in school settings. There has been extensive discussion in the academic literature and popular media on psychosocial outcomes (e.g. anxiety, depression, loneliness) and equity and equality outcomes (e.g. implications for sex and gender equality for parents or schoolchildren, disadvantages for children or parents from low‐income families) in relation to school closures. However, less attention has been paid to these outcomes in relation to reopened schools with risk mitigation measures in place. How do such measures affect children’s mental health? Are some groups of children (and, indeed, parents and teachers) impacted more than others?

Prominent gaps also exist with regard to interventions. For example, measures that reduce the opportunity for contacts are widely used, and many have been evaluated for their effectiveness at reducing SARS‐CoV‐2 spread (Krishnaratne 2022). However, the unintended consequences of measures like the implementation of fixed groups, alternating physical presence, and staggered arrival, departure, and break times have not been widely studied.

Additionally, primary authors should report sufficient contextual factors and demographic data in order to ensure analyses of such are feasible to assist decision‐makers in making appropriately nuanced decisions for their circumstances.

Whilst this scoping review was designed to provide a systematic overview of the available evidence, we did not aim to synthesise the evidence on unintended consequences. With more primary research and evidence emerging over time, such an analysis could be valuable to decision‐makers. We conclude that more focused primary research is needed to fill the gaps and give a broader picture of the diverse unintended consequences of school‐based measures before a more thorough synthesis is warranted. Education or practice recommendations about the likely balance of benefits and harms of these interventions can only be derived from the availability of a more complete evidence base.

Acknowledgements

Cochrane Public Health supported the authors in the development of this scoping review. The following people conducted the editorial process.

Sign‐off Editor (final editorial decision): Lisa Bero, University of Sydney, Australia

Managing Editor (selected peer reviewers, collated peer‐reviewer comments, provided editorial guidance to authors, edited the article): Joey Kwong, Cochrane Central Editorial Service

Editorial Assistant (conducted editorial policy checks and supported editorial team): Leticia Rodrigues, Cochrane Central Editorial Service

Copy Editor (copy‐editing and production): Lisa Winer, c/o Cochrane Copy Edit Support

Peer reviewers (provided comments and recommended an editorial decision): Wanli Tan, Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology (clinical review); Abbey Masonbrink, Children's Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, University of Missouri, Kansas City School of Medicine (clinical review); Micah Peters, University of South Australia, Clinical and Health Sciences, Rosemary Bryant AO Research Centre (clinical/method review); Kate Zinszer, University of Montreal (clinical review); Stella O'Brien (consumer review); Robert Walton, Cochrane UK (summary versions review); Rachel Richardson, Cochrane Evidence Production & Methods Directorate (methods review); Douglas Salzwedel, Cochrane Hypertension (search review). One additional peer reviewer provided clinical peer review but chose not to be publicly acknowledged.

We acknowledge Maria‐Inti Metzendorf of Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders for peer reviewing the primary database strategy and search methods at the protocol stage.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Completed PRISMA ScR Checklist

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA‐ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED (SECTION) |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | See Title |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | See Abstract |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | See Objectives |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g. population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualise the review questions and/or objectives. | See Objectives |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g. a web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | See Methods |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g. years considered, language, and publication status) and provide a rationale. | See Methods |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g. databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | See Methods |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | See Appendix 2 |

| Selection of sources of evidence | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e. screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | See Methods |

| Data charting process | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g. calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | See Methods |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | See Methods |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | Not applicable |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarising the data that were charted. | Not applicable |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | See Figure 2 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | See Characteristics of studies |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | Not applicable |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | Not applicable |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarise and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | See Results |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarise the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | See Results |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | See Discussion |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | See Conclusion |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | See Sources of Support |

Appendix 2. Search strategies

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946 to March 25, 2021

Date search conducted: March 26, 2021

Strategy:

1 Coronavirus/ (4569)

2 Coronavirus Infections/ (44655)

3 COVID‐19/ (66730)

4 SARS‐CoV‐2/ (51921)

5 (2019 nCoV or 2019nCoV or 2019‐novel CoV).tw,kf. (1599)

6 (corona vir* or coronavir* or neocorona vir* or neocoronavir*).tw,kf. (59273)

7 COVID.mp. (113023)

8 COVID19.tw,kf. (1304)

9 (nCov 2019 or nCov 19).tw,kf. (132)

10 ("SARS‐CoV‐2" or "SARS‐CoV2" or SARSCoV2 or "SARSCoV‐2").tw,kf. (38374)

11 ("SARS coronavirus 2" or "SARS‐like coronavirus" or "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus‐2").tw,kf. (12207)

12 or/1‐11 [Set 1: SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID‐19] (131988)

13 exp School Health Services/ (23430)

14 School Teachers/ (1733)

15 Schools/ (40299)

16 Students/ (62244)

17 ((campus* or class* or employee* or pupil* or staff* or student$1 or teacher$1) adj3 (college$1 or elementary or junior or middle* or primary or secondary)).tw,kf. (55342)

18 (educational adj1 (institution$1 or setting$1)).tw,kf. (3911)

19 (gradeschool* or highschool* or kindergarten* or school* or schoolbus*).tw,kf. (301694)

20 or/13‐19 [Set 2: Primary or secondary school settings] (382822)

21 exp Communicable Disease Control/ (359385)

22 exp COVID‐19 Testing/ (4673)

23 COVID‐19 Vaccines/ (1862)

24 Disease Outbreaks/pc (15339)

25 Disease Transmission, Infectious/pc (4892)

26 Disinfection/ (15446)

27 exp Hand Hygiene/ (7297)

28 Health Education/ (61484)

29 Masks/ (5284)

30 exp Mass Screening/ (131909)

31 Ventilation/ (5889)

32 air purifier$1.tw,kf. (176)

33 ((activit* or building$1 or classroom* or environment* or room* or space$1) adj3 (adapt* or chang* or modif*)).tw,kf. (132546)

34 (alternat* adj3 presen*).tw,kf. (9977)

35 ((avoid* or limit* or reduc* or restrict*) adj3 contact*).tw,kf. (7653)

36 (clean* or disinfect* or sanitation* or saniti*).tw,kf. (134845)

37 ((cohort$1 or contact$1 or group$1) adj3 (fix* or limit* or reduc* or restrict* or small*)).tw,kf. (103801)

38 cohort$1 siz*.tw,kf. (759)

39 confinement.tw,kf. (20910)

40 (contact$1 adj2 (investigat* or notif* or screen* or test* or trac*)).tw,kf. (7164)

41 (distanc* adj2 (physical* or social*)).tw,kf. (7402)

42 (facemask* or face cover*).tw,kf. (1700)

43 (hand$1 adj2 (hygiene or wash*)).tw,kf. (8855)

44 handwash*.tw,kf. (2381)

45 ((health promotion or hygiene or non‐pharm* or nonpharm* or organi?ation* or policies or policy or population health or prevention or public health or structural) adj3 (intervention$1 or program* or measure$1)).tw,kf. (120352)

46 (lock down* or lockdown*).tw,kf. (5914)

47 mask*.tw,kf. (83967)

48 ((measur* or tak*) adj2 temperature*).tw,kf. (17272)

49 (outbreak adj2 respon*).tw,kf. (968)

50 quarantin*.tw,kf. (7891)

51 stay at home order*.tw,kf. (384)

52 surveillance.tw,kf. (192878)

53 vaccin*.tw,kf. (333796)

54 ventilat*.tw,kf. (175464)

55 or/21‐54 [Set 3: Control measures] (1710896)

56 Absenteeism/ (9256)

57 Anxiety/ (85754)

58 exp Behavioral Symptoms/ (383687)

59 Body Mass Index/ (131743)

60 exp Dyssomnias/ (70791)

61 Eczema/ (11128)

62 Gender Equity/ (83)

63 Hand Dermatoses/ (7803)

64 Harm Reduction/ (3294)

65 Healthcare Disparities/ (18504)

66 Mental Health/ (42311)

67 exp Occupational Stress/ (15013)

68 Resilience, Psychological/ (6587)

69 exp Risk Assessment/ (282104)

70 exp Social Isolation/ (18947)

71 exp Socioeconomic Factors/ (463285)

72 Stress, Psychological/ (124276)

73 Weight Gain/ (32169)

74 Workload/ (22072)

75 absent*.tw,kf. (161713)

76 ((adverse or harm* or iatrogenic or unwanted) adj3 (consequence* or effect$1 or event* or outcome$1 or impact$1 or reaction$1 or result*)).tw,kf. (520644)

77 ((alienat* or exclu* or isolat*) adj2 social*).tw,kf. (12315)

78 (anxi* or depress* or mental health or stress*).tw,kf. (1534594)

79 (behavi* adj2 (problem* or symptom*)).tw,kf. (32951)

80 (BMI or body mass index).tw,kf. (262223)

81 ((benefi* or paradox* or surpris* or unanticipated or uninten* or unpredict*) adj3 (consequence* or effect$1 or event* or outcome$1 or impact$1 or reaction$1 or result*)).tw,kf. (173737)

82 ((career* or job or professional*) adj2 (opportunit* or train*)).tw,kf. (12835)

83 (cost* or economic* or expens* or expenditure* or income*).tw,kf. (1086696)

84 (dermat* or eczema).tw,kf. (188421)

85 disrupt*.tw,kf. (305486)

86 (equalit* or equit* or disadvantag* or discriminat* or disparit* or inequalit* or inequit*).tw,kf. (460831)

87 (fair* or unfair*).tw,kf. (92082)

88 ((fail* or perform*) adj2 (grade* or school*)).tw,kf. (8174)

89 ((gain* or increas*) adj2 weight).tw,kf. (95123)

90 (health* adj3 (consequence* or effect$1 or event* or outcome$1 or impact$1 or reaction$1 or result*)).tw,kf. (234382)

91 lonel*.tw,kf. (8446)

92 ((los* or miss*) adj2 (day$1 or schoolday$1)).tw,kf. (6827)

93 resilienc*.tw,kf. (31453)

94 side effect*.tw,kf. (264731)

95 sleep*.tw,kf. (193948)

96 (well‐being or wellbeing or wellness).tw,kf. (111246)

97 (work load* or workload*).tw,kf. (33948)

98 or/56‐97 [Set 4: Unintentional effects] (5570751)

99 and/12,20,55 [Sets 1 and 2 and 3: SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID control measures implemented in the school setting] (1364)

100 and/12,20,98 [Sets 1 and 2 and 4: SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID unintentional effects of school measures] (1388)

101 99 or 100 [Combined results: SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID control measures implemented in the school setting or unintentional effects of school measures] (2009)

102 limit 101 to yr="2020‐Current" (1990)

103 remove duplicates from 102 [MEDLINE results for export] (1952)

Database: Ovid Embase 1974 to 2021 March 25

Date search conducted: March 26, 2021

Strategy:

1 coronaviridae/ (1133)

2 exp coronavirinae/ (23463)

3 coronavirus disease 2019/ (97950)

4 exp coronavirus infection/ (24540)

5 sars‐related coronavirus/ (471)

6 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2/ (24694)

7 (2019 nCoV or 2019nCoV or 2019‐novel CoV).ti,ab,kw. (1602)

8 (corona vir* or coronavir* or neocorona vir* or neocoronavir*).ti,ab,kw. (59048)

9 COVID.mp. (103527)

10 COVID19.ti,ab,kw. (1700)

11 (nCov 2019 or nCov 19).ti,ab,kw. (104)

12 ("SARS‐CoV‐2" or "SARS‐CoV2" or SARSCoV2 or "SARSCoV‐2").ti,ab,kw. (37437)

13 ("SARS coronavirus 2" or "SARS‐like coronavirus" or "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus‐2").ti,ab,kw. (11447)

14 or/1‐13 [Set 1: SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID‐19] (144799)

15 elementary student/ (1590)

16 high school/ (21990)

17 high school student/ (8306)

18 kindergarten/ (3048)

19 middle school/ (1916)

20 middle school student/ (1458)

21 primary school/ (13510)

22 *school/ (18067)

23 exp school health service/ (19728)

24 school teacher/ (1762)

25 *student/ (26784)

26 ((campus* or class* or employee* or pupil* or staff* or student$1 or teacher$1) adj3 (college$1 or elementary or junior or middle* or primary or secondary)).ti,ab,kw. (69443)

27 (educational adj1 (institution$1 or setting$1)).ti,ab,kw. (4917)

28 (gradeschool* or highschool* or kindergarten* or school* or schoolbus*).ti,ab,kw. (368581)

29 or/15‐28 [Set 2: Primary or secondary school settings] (447164)

30 air conditioning/ (23129)

31 air filter/ (1103)

32 exp communicable disease control/ (122606)

33 COVID‐19 testing/ (597)

34 exp disinfection/ (28291)

35 epidemic/pc (8001)

36 face mask/ (8774)

37 exp hand washing/ (16349)

38 pediatric face mask/ (115)

39 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine/ (1619)

40 school health education/ (819)

41 air purifier$1.ti,ab,kw. (239)

42 ((activit* or building$1 or classroom* or environment* or room* or space$1) adj3 (adapt* or chang* or modif*)).ti,ab,kw. (153993)

43 (alternat* adj3 presen*).ti,ab,kw. (12095)

44 ((avoid* or limit* or reduc* or restrict*) adj3 contact*).ti,ab,kw. (9216)

45 (clean* or disinfect* or sanitation* or saniti*).ti,ab,kw. (168872)

46 ((cohort$1 or contact$1 or group$1) adj3 (fix* or limit* or reduc* or restrict* or small*)).ti,ab,kw. (156270)

47 cohort$1 siz*.ti,ab,kw. (1457)

48 confinement.ti,ab,kw. (16262)

49 (contact$1 adj2 (investigat* or notif* or screen* or test* or trac*)).ti,ab,kw. (8479)

50 (distanc* adj2 (physical* or social*)).ti,ab,kw. (7392)

51 (facemask* or face cover*).ti,ab,kw. (2307)

52 (hand$1 adj2 (hygiene or wash*)).ti,ab,kw. (13094)

53 handwash*.ti,ab,kw. (2868)

54 ((health promotion or hygiene or non‐pharm* or nonpharm* or organi?ation* or policies or policy or population health or prevention or public health or structural) adj3 (intervention$1 or program* or measure$1)).ti,ab,kw. (148865)

55 (lock down* or lockdown*).ti,ab,kw. (5409)

56 mask*.ti,ab,kw. (104426)

57 ((measur* or tak*) adj2 temperature*).ti,ab,kw. (18169)

58 (outbreak adj2 respon*).ti,ab,kw. (1086)

59 quarantin*.ti,ab,kw. (7703)

60 stay at home order*.ti,ab,kw. (337)

61 surveillance.ti,ab,kw. (268371)

62 vaccin*.ti,ab,kw. (384114)

63 ventilat*.ti,ab,kw. (259256)

64 or/30‐63 [Set 3: Control measures] (1754121)

65 absenteeism/ (17934)

66 exp adolescent behaviour/ (13319)

67 anxiety/ (220750)

68 body mass/ (478592)

69 body weight gain/ (21181)

70 body weight change/ (4400)

71 exp child behaviour/ (50809)

72 exp dermatitis/ (159811)

73 harm reduction/ (7029)

74 health equity/ (4235)

75 mental health/ (150661)

76 psychological resilience/ (4858)

77 psychological well‐being/ (21253)

78 risk assessment/ (609450)

79 exp sleep disorder/ (250987)

80 exp social isolation/ (25418)

81 exp socioeconomics/ (402736)

82 exp stress/ (325523)

83 workload/ (46453)

84 absent*.ti,ab,kw. (211082)

85 ((adverse or harm* or iatrogenic or unwanted) adj3 (consequence* or effect$1 or event* or outcome$1 or impact$1 or reaction$1 or result*)).ti,ab,kw. (815584)

86 ((alienat* or exclu* or isolat*) adj2 social*).ti,ab,kw. (16271)

87 (anxi* or depress* or mental health or stress*).ti,ab,kw. (1989689)

88 (behavi* adj2 (problem* or symptom*)).ti,ab,kw. (43220)

89 (BMI or body mass index).ti,ab,kw. (480243)

90 ((benefi* or paradox* or surpris* or unanticipated or uninten* or unpredict*) adj3 (consequence* or effect$1 or event* or outcome$1 or impact$1 or reaction$1 or result*)).ti,ab,kw. (233664)

91 ((career* or job or professional*) adj2 (opportunit* or train*)).ti,ab,kw. (17153)

92 (cost* or economic* or expens* or expenditure* or income*).ti,ab,kw. (1408988)

93 (dermat* or eczema).ti,ab,kw. (271309)

94 disrupt*.ti,ab,kw. (386186)

95 (equalit* or equit* or disadvantag* or discriminat* or disparit* or inequalit* or inequit*).ti,ab,kw. (573394)

96 (fair* or unfair*).ti,ab,kw. (117172)

97 ((fail* or perform*) adj2 (grade* or school*)).ti,ab,kw. (11057)

98 ((gain* or increas*) adj2 weight).ti,ab,kw. (130940)

99 (health* adj3 (consequence* or effect$1 or event* or outcome$1 or impact$1 or reaction$1 or result*)).ti,ab,kw. (339171)

100 lonel*.ti,ab,kw. (10503)

101 ((los* or miss*) adj2 (day$1 or schoolday$1)).ti,ab,kw. (12541)

102 resilienc*.ti,ab,kw. (37425)

103 side effect*.ti,ab,kw. (388105)

104 sleep*.ti,ab,kw. (294029)

105 (well‐being or wellbeing or wellness).ti,ab,kw. (145787)

106 (work load* or workload*).ti,ab,kw. (47358)

107 or/65‐106 [Set 4: Unintentional effects] (7600252)

108 and/14,29,64 [Sets 1 and 2 and 3: SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID control measures implemented in the school setting] (1225)

109 and/14,29,107 [Sets 1 and 2 and 4: SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID unintentional effects of school measures] (1285)

110 108 or 109 [Combined results: SARS‐CoV‐2/COVID control measures implemented in the school setting or unintentional effects of school measures] (1841)

111 limit 110 to yr="2020‐Current" (1738)

112 remove duplicates from 111 [Embase results for export] (1720)

Database: Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register

URL:https://covid-19.cochrane.org/ (searched via the Cochrane Register of Studies: https://crsweb.cochrane.org/)

Date search conducted: March 26, 2021

Strategy:

1 ((campus* OR class* OR employee* OR pupil* OR staff* OR student* OR teacher*) ADJ3 (college* or elementary OR junior OR middle* OR primary OR secondary)):TI,AB AND INREGISTER 320

2 (educational NEXT setting*):TI,AB AND INREGISTER 6

3 (gradeschool* OR highschool* OR kindergarten* OR school* OR schoolbus*):TI,AB AND INREGISTER 1182

4 #1 OR #2 OR #3 1425

5 Prevention AND INREGISTER 6372

6 #4 AND #5 300

Database: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 2)

URL: searched via the Cochrane Register of Studies: https://crsweb.cochrane.org/

Date search conducted: March 26, 2021

Strategy:

1 Coronavirus:MH AND CENTRAL:TARGET 694

2 "Coronavirus Infections":MH AND CENTRAL:TARGET 681

3 "COVID‐19":MH AND CENTRAL:TARGET 222

4 "SARS‐CoV‐2":MH AND CENTRAL:TARGET 160

5 ("2019 nCoV" OR 2019nCoV OR "corona virus*" OR coronavirus* OR COVID OR COVID19 OR "nCov 2019" OR "SARS‐CoV2" OR "SARS CoV‐2" OR SARSCoV2 OR "SARSCoV‐2"):TI,AB AND CENTRAL:TARGET 5100

6 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 5119

7 ((campus* OR class* OR employee* OR pupil* OR staff* OR student* OR teacher*) ADJ3 (college* or elementary OR junior OR middle* OR primary OR secondary)):TI,AB AND CENTRAL:TARGET 7166

8 (educational NEXT setting*):TI,AB AND CENTRAL:TARGET 135

9 (gradeschool* OR highschool* OR kindergarten* OR school* OR schoolbus*):TI,AB AND CENTRAL:TARGET 28505

10 #7 OR #8 OR #9 AND CENTRAL:TARGET 33330

11 #6 AND #10 103

12 2020 TO 2021:YR AND CENTRAL:TARGET 114829

13 #11 AND #12 99

Database: Clarivate Web of Science Core Collection: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) ‐‐1900‐present; Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) ‐‐1900‐present; Emerging Sources Index (ESCI) ‐‐ 2005‐present

URL:https://webofknowledge.com

Date search conducted: March 26, 2021

Strategy:

| # 7 | 1,903 | #6 OR #5 Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, ESCI Timespan=2020‐2021 |

||

| # 6 | 1,402 | #4 AND #2 AND #1 Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, ESCI Timespan=2020‐2021 |

||

| # 5 | 1,142 | #3 AND #2 AND #1 Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, ESCI Timespan=2020‐2021 |

||