Neural stem cells exist in the adult brain of mammals, and these stem cells can differentiate into neurons in specific regions like the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus through a process called adult neurogenesis (1). In the hippocampus, these newly born neurons play a critical role in learning and memory. In particular, they are critical for our ability to distinguish between objects, places, emotions, and events that are similar to each other, a process called pattern separation. There is a decline in adult neurogenesis with age, and this decline correlates with a decline in learning, memory, and emotional balance (2–4). Since neurogenesis is a process, measuring it can be complicated. In PNAS, Kandel et al. (5) make substantial progress. The experimental “gold standard” has been to pulse neural stem cells with cell cycle indicators like BrdU or EdU or radiocarbon to label dividing neural stem cells and then to double-label postmortem brains at a subsequent time with a mature neuronal marker (6, 7). This approach allows determination of whether the BrdU or EdU has colocalized with the mature neuronal marker, indicating that neurogenesis has occurred. A less precise approach and one prone to contradictions is the use of antibodies to a protein or RNA transcripts that are thought to be specific for a particular state of adult neurogenesis (2–4, 8–10).

A better approach would be to identify an indicator of neurogenesis that can be detected in vivo, so the process of neurogenesis can be monitored in a living organism. In 2007, the authors (5) identified an NMR spectroscopy signal that correlates with neurogenesis in mice and humans (11). This signal resonates at 1.28 ppm, a frequency that corresponds to the saturated hydrocarbon groups that characterize all fatty acids in mice and humans. They also showed that blocking fatty acid synthetase blocked running-induced adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus. In ref. 5, the authors identify oleic acid (18:1ω9 monounsaturated fatty acid [MUFA]) as the 1.28-ppm signal, and, importantly, they reveal that oleic acid (18:1ω9 MUFA) is the long-sought-after endogenous ligand that binds the previous orphan nuclear receptor TLX/NR2E1 (12). What makes this finding particularly interesting is that TLX has previously been repeatedly shown to regulate adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus (13–16). In vertebrates, TLX is specifically localized to the neurogenic regions of the forebrain, including the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and retina, throughout development and adulthood. TLX regulates the expression of genes involved in multiple pathways such as the cell cycle, DNA replication, and cell adhesion. These roles are primarily performed through the intricate and elegantly timed switch between transcriptional repression and activation of downstream target genes that regulate proliferation of neural stem cells, as well as the initiation of maturation.

Kandel et al. (5) demonstrate that MUFAs are enriched in neural stem and progenitor cells and are critical for their proliferation and survival. Blocking MUFA generation by inhibition of stearoyl-CoA desaturases, which are enzymes required for the production of MUFAs from saturated fatty acids, reduced the proliferation and/or survival of human neural progenitor cells. Remarkably, supplementing oleic acid (18:1ω9 MUFA) but not 18:0 saturated fatty acids rescued the neural progenitor population, providing strong evidence that MUFAs play an important role in neural progenitor cell proliferation and/or survival. Consistent with the in vitro study, a high concentration of MUFAs was detected in the dentate gyrus of mouse hippocampus. Inhibition of stearoyl-CoA desaturases led to a substantial reduction in neural stem and progenitor cell proliferation in the hippocampus.

How do MUFAs regulate neural stem and progenitor cell proliferation and neurogenesis? Because the nuclear receptor TLX has been shown to be an essential regulator of neural stem cell proliferation/self-renewal and hippocampal neurogenesis (13, 14), the authors (5) asked whether MUFAs could bind to TLX to regulate its activity and, in turn, modulate neural stem cell proliferation and neurogenesis. Molecular docking revealed that fatty acids could fit into the presumed binding pocket of the TLX ligand-binding domain. Encouraged by the virtual analysis result, the authors (5) next tested the physical interaction of fatty acids with the TLX ligand-binding domain, using biolayer interferometry, a biosensing technology designed for detection of ligand–receptor interaction, and they detected saturable binding of oleic acid (18:1ω9 MUFA) to the TLX ligand-binding domain, with a Kd of 7.3 µM. In contrast, no specific binding of saturated fatty acids (e.g., stearic acid, 18:0) or polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g., linolenic acid, 18:3ω3) to the TLX ligand-binding domain could be detected in the same assay. These results from Kandel et al. provide evidence that MUFAs such as oleic acid fulfill the prerequisite of being a TLX ligand, by having the ability to physically interact with the TLX ligand-binding domain.

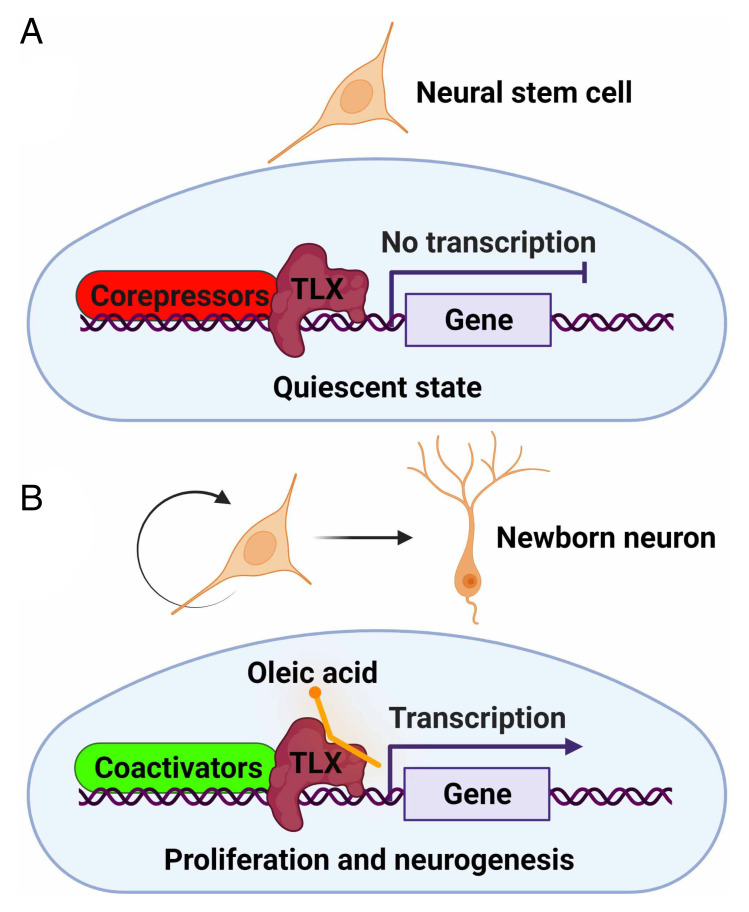

To qualify as a ligand, oleic acid needs to be able to modulate TLX activity upon binding to the TLX ligand-binding domain. Because TLX has been shown to function as a transcriptional repressor by interacting with corepressors (17–19), Kandel et al. (5) tested whether oleic acid could modulate TLX–corepressor interactions. Indeed, they found that oleic acid could inhibit the interaction of the TLX ligand-binding domain with a peptide of atrophin, a corepressor for TLX (17), in a dose-dependent manner. Accordingly, the authors demonstrated that oleic acid could also promote coactivator recruitment to the TLX ligand-binding domain in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, the authors cotransfected a TLX expression vector and a TLX-responsive luciferase reporter into HeLa cells and showed that TLX repressed the luciferase reporter activity, consistent with previous studies (13, 14, 17–19). Interestingly, treatment with oleic acid led to a modest activation of the luciferase reporter in TLX-expressing cells, resulting in derepression of the reporter activity. These results together demonstrate that oleic acid could serve as a TLX ligand by binding to the TLX ligand-binding domain and could facilitate the dissociation of transcriptional corepressors from and the recruitment of transcriptional coactivators to the TLX ligand-binding domain to derepress or activate TLX-responsive genes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Oleic acid binding to the nuclear receptor TLX promotes hippocampal neurogenesis. (A) In the absence of oleic acid, TLX is associated with corepressors; thus, transcription at its target genes is repressed, and neural stem cells are maintained in a quiescent state. (B) When oleic acid is bound to TLX, corepressors are dissociated from TLX; instead, transcriptional coactivators are recruited to promote transcription at TLX target genes, leading to cell cycle progression and neurogenesis. The figure was created with BioRender.com.

To determine the effect of oleic acid treatment on neural stem cell proliferation and hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo, Kandel et al. (5) treated young (2-mo-old) and old (24-mo-old) mice with oleic acid by stereotactic injection to the dentate gyrus. Treatment with oleic acid led to increased numbers of neural stem cells in both young and old mice. Oleic acid treatment also increased the number of newborn neurons in young mice. Of note is that the increase of proliferating neural stem cells induced by oleic acid is TLX dose dependent, with the highest increase in wild-type mice that carry two copies of the TLX gene, an intermediate increase in heterozygous mice with one copy of the TLX gene, and no effect in TLX knockout (KO) mice.

Consistent with the role of oleic acid in promoting neural stem and progenitor cell proliferation and neurogenesis, the authors (5) detected up-regulated expression of genes in cell cycle progression and neurogenesis/gliogenesis (collectively referred to as neurogenesis). To evaluate the TLX-dependent effect of oleic acid, the authors generated an elegant mouse model (by crossing Lfng-CreERT2; RCL-tdT mice with TLXloxp/loxp mice, and then with Lfng-eGFP mice) that carried both wild-type and TLX KO neural stem cells in the same dentate gyrus. Moreover, the wild-type and TLX KO neural stem cells were labeled by fluorescent reporters differentially. These mice were mock treated or injected with oleic acid, and neural stem cells were isolated from the dentate gyrus of the treated mice. Comparing the expression profile of the wild-type with the TLX KO neural stem cells isolated from the treated mice revealed that 32 cell cycle–related and 32 neurogenesis-related genes were induced by oleic acid in a TLX-dependent manner. The induction was seen in wild-type but not in TLX KO neural stem cells. Together, these results support a key role for TLX in regulating neural stem cell proliferation and hippocampal neurogenesis as well as the potential of oleic acid in modulating neurogenesis through TLX.

Of interest is that both PAX6 and SOX2 expression are regulated by TLX and oleic acid, reinforcing the idea that TLX is a master regulator of neural stem cells (13), acting upstream of PAX6 and SOX2. It is worth noting that a higher induction of neurogenesis-related genes was achieved by TLX KO as compared to oleic acid–induced TLX activation, suggesting that oleic acid can only partially derepress neurogenesis-related genes. On the other hand, a weaker induction of cell cycle–related genes was attained by TLX KO as compared to oleic acid–induced activation, indicating that oleic acid can activate cell cycle–related genes beyond derepression. How many of these genes are direct TLX targets remains to be verified. How oleic acid regulates TLX target genes in a context-dependent manner will be of interest for future mechanistic studies. It will also be important to understand how oleic acid and/or other endogenous TLX ligands regulate the transitions from quiescent neural stem cells to rapidly amplifying progenitor cells and then to differentiated neurons and glia. Finally, uncovering the mechanisms that establish intracellular and extracellular oleic acid concentration gradients to fine-tune TLX activity and neural progenitor cell fate may shed light on the role of the neurogenic niche in adult neurogenesis.

While the discovery of the ligand for TLX is important in and of itself, knowing what the ligand is will allow for more detailed experiments to reveal the mechanism for how TLX orchestrates adult neurogenesis. In addition, this study validates oleic acid (18:1ω9 MUFA) as a constituent of the 1.28-ppm signal, thus providing a valuable tool to monitor adult neurogenesis in vivo in mice and nonhuman primates as well as humans. This method of in vivo monitoring of adult neurogenesis will be particularly valuable in clinical trials for drugs that are designed to target neurogenesis for neurodegenerative diseases where neurogenesis has been shown to be dysregulated (20). Finally, as the authors (5) point out, oleic acid is now a meaningful target for discovering drugs designed to increase or decrease neurogenesis in disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Gage and J. Cerneckis for editing, and J. Cerneckis for preparing the figure and legend.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

See companion article, “Oleic acid is an endogenous ligand of TLX/NR2E1 that triggers hippocampal neurogenesis,” 10.1073/pnas.2023784119.

References

- 1.Gage F. H., Mammalian neural stem cells. Science 287, 1433–1438 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreno-Jiménez E. P., et al. , Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 25, 554–560 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobin M. K., et al. , Human hippocampal neurogenesis persists in aged adults and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Cell Stem Cell 24, 974–982.e3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boldrini M., et al. , Human hippocampal neurogenesis persists throughout aging. Cell Stem Cell 22, 589–599.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandel P., et al. , Oleic acid is an endogenous ligand of TLX/NR2E1 that triggers hippocampal neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, 10.1073/pnas.2023784119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksson P. S., et al. , Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat. Med. 4, 1313–1317 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spalding K. L., Bhardwaj R. D., Buchholz B. A., Druid H., Frisén J., Retrospective birth dating of cells in humans. Cell 122, 133–143 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franjic D., et al. , Transcriptomic taxonomy and neurogenic trajectories of adult human, macaque, and pig hippocampal and entorhinal cells. Neuron 110, 452–469.e14 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorrells S. F., et al. , Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature 555, 377–381 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terreros-Roncal J., et al. , Impact of neurodegenerative diseases on human adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science 374, 1106–1113 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manganas L. N., et al. , Magnetic resonance spectroscopy identifies neural progenitor cells in the live human brain. Science 318, 980–985 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu R. T., McKeown M., Evans R. M., Umesono K., Relationship between Drosophila gap gene tailless and a vertebrate nuclear receptor Tlx. Nature 370, 375–379 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Y., et al. , Expression and function of orphan nuclear receptor TLX in adult neural stem cells. Nature 427, 78–83 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C. L., Zou Y., He W., Gage F. H., Evans R. M., A role for adult TLX-positive neural stem cells in learning and behaviour. Nature 451, 1004–1007 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qu Q., et al. , Orphan nuclear receptor TLX activates Wnt/beta-catenin signalling to stimulate neural stem cell proliferation and self-renewal. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 31–40, 1–9 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murai K., et al. , Nuclear receptor TLX stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis and enhances learning and memory in a transgenic mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9115–9120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang C. L., Zou Y., Yu R. T., Gage F. H., Evans R. M., Nuclear receptor TLX prevents retinal dystrophy and recruits the corepressor atrophin1. Genes Dev. 20, 1308–1320 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokoyama A., Takezawa S., Schüle R., Kitagawa H., Kato S., Transrepressive function of TLX requires the histone demethylase LSD1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 3995–4003 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun G., Yu R. T., Evans R. M., Shi Y., Orphan nuclear receptor TLX recruits histone deacetylases to repress transcription and regulate neural stem cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15282–15287 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gage F. H., Adult neurogenesis in neurological diseases. Science 374, 1049–1050 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]