Abstract

Biotransformation of 2-chlorophenol by a methanogenic sediment community resulted in the transient accumulation of phenol and benzoate. 3-Chlorobenzoate was a more persistent product of 2-chlorophenol metabolism. The anaerobic biotransformation of phenol to benzoate presumably occurred via para-carboxylation and dehydroxylation reactions, which may also explain the observed conversion of 2-chlorophenol to 3-chlorobenzoate.

Anaerobic biotransformation of a wide variety of aromatic compounds initially involves the formation of a carboxyl group on the aromatic nucleus, e.g., via a carboxylation reaction (6). An anaerobic isolate (21) and a coculture (9) that are able to carboxylate phenol have been characterized. Other aromatics that undergo anaerobic carboxylation include simple polyaromatic hydrocarbons (22), aniline (8), o-cresol (2), and m-cresol (12). However, under anaerobic conditions, biotransformation of most halogenated aromatic compounds is typically initiated by reductive dehalogenation (14). In fact, it appears that removal of the halogen substituent must occur before anaerobic cleavage of the aromatic nucleus is feasible (19). Indeed, in nearly all previous studies, anaerobic transformation of 2-chlorophenol (2-CP) by mixed cultures occurred solely via reductive dehalogenation to phenol (e.g., see references 4 and 15). The pathway by which phenol is biodegraded in mixed cultures under methanogenic conditions has been examined in a number of investigations (e.g., see references 16 and 18). The results of these recent studies indicate that 4-hydroxybenzoate is formed via para-carboxylation of phenol and subsequently dehydroxylated to yield benzoate, which undergoes ring cleavage and ultimately is mineralized.

However, in some cases, more than one pathway may be possible for the biotransformation of aromatic compounds in mixed anaerobic cultures. Which pathway is operative may determine whether or not the parent compound is ultimately mineralized. For example, Londry and Fedorak (12) examined the biotransformation of m-cresol in a methanogenic consortium. Biotransformation of m-cresol initially proceeded via para-carboxylation to yield 4-hydroxy-2-methylbenzoic acid. Metabolism of this intermediate appeared to be the rate-limiting step in the biotransformation of m-cresol. 4-Hydroxy-2-methylbenzoate predominantly underwent demethylation to yield 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, which was ultimately converted to acetate via reductive dehydroxylation to benzoate and subsequent ring cleavage. However, “premature” reductive dehydroxylation of 4-hydroxy-2-methylbenzoate produced a minor metabolite, 2-methylbenzoate, which persisted.

The existence of two m-cresol biotransformation pathways, one leading to mineralization of the parent compound and the other resulting in the production of a persistent substituted benzoate, points to the importance of understanding biotransformation pathways. This information is necessary for predicting the fate of organic pollutants in the environment and for designing bioremediation strategies and wastewater treatment processes. In this paper, we report that in mixed anaerobic cultures, in addition to undergoing the expected pathway of reductive dehalogenation to phenol and ultimate mineralization, transformation of 2-CP may initially involve the formation of a carboxyl group analogous to the anaerobic biotransformation of nonhalogenated aromatic compounds.

Establishment of cultures.

Strict anaerobic and aseptic techniques were used throughout the experiments. Experiments were performed with batch reactors consisting of 160-ml or 2-liter glass vessels with serum bottle closures. The glass vessels were sealed with thick black butyl septa and aluminum crimp caps. All of the reactors had the same ratio of headspace volume to slurry-phase volume (3:5, vol/vol). The slurry phase was composed of sediment and anaerobic medium (1:9, vol/vol). The anaerobic sediment inoculum was collected from a depth of 100 m at a site located approximately 16 km east of Fox Point, Wisconsin, in Lake Michigan by using a box corer, transferred to canning jars, and stored at 4°C for approximately three months until used. The techniques used for medium preparation, culture handling, and sampling were based on previously described methods (13). The anaerobic medium used for this study has been previously described (5) and was prepared by combining separate sterile, anoxic solutions of salts, bicarbonate buffer, and reducing agents with the remaining medium components. The sediment inoculum was added to the glass vessels inside an anaerobic glove box (85% N2–10% CO2–5% H2; Coy Laboratories, Ann Arbor, Mich.), and the bicarbonate buffer was equilibrated with 30% CO2–70% N2. 2-CP was added to a final concentration of 200 μM. One 2-liter reactor and two 160-ml viable reactors were prepared in this manner. In the interest of brevity, only the results obtained with the duplicate 160-ml reactors are presented here. Except where noted, the results obtained with the 2-liter reactor were similar. A 2-liter sterile control was prepared in the same manner as the viable reactors, except that the sediment inoculum was autoclaved for 1 h on each of three consecutive days before being combined with sterile medium and 2-CP. The reactors were incubated statically at 30°C.

Analysis of aromatic compounds.

The reactors were continuously shaken on a platform shaker (100 rpm) during sampling events. Slurry-phase samples were taken by using deoxygenated and sterile disposable syringes, filtered (0.45-μm pore size; Gelman Acrodisc), and either analyzed immediately or frozen (−20°C) prior to analysis. The aqueous concentrations of 2-CP and its aromatic metabolites were determined by using a reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography system (Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a computer interface and D-7000 HSM software (Hitachi). Separations were performed by using a mobile phase of methanol-water-acetic acid (60:38:2, vol/vol) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min and a C18 column (4.7 mm by 235 mm) (Partisil 5 ODS-3; Whatman International Ltd.). Detection was by UV absorbance with a diode array detector (Hitachi, model L-4500) operated at 280 nm. Linear calibration factors were determined from external standards, which were injected along with each sample set. Identification of aromatic metabolites of 2-CP biotransformation was based on comparison of their retention times and UV spectra (250 to 380 nm) with those of authentic compounds.

2-CP fate.

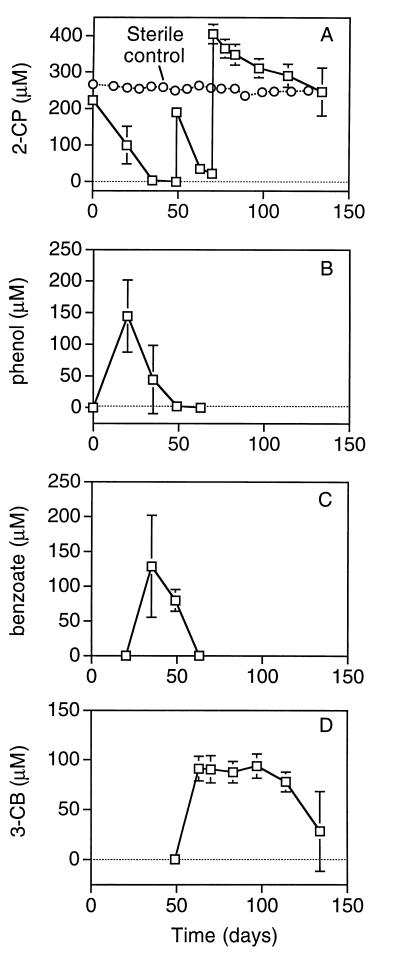

Complete removal of 2-CP was observed in the viable reactors within 50 days, as shown for the duplicate 160-ml reactors in Fig. 1A. The concentration of 2-CP in the 2-liter sterile control remained nearly constant during this period, which indicates that transformation of 2-CP in the viable reactors was due to biological activity. Whenever 2-CP was no longer detectable in the sediment slurry reactors, it was replenished.

FIG. 1.

Anaerobic biotransformation of 2-CP in the sediment community (A) and corresponding production of phenol (B), benzoate (C), and 3-CB (D). Squares represent the average concentrations in duplicate 160-ml batch slurry reactors. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation. Circles represent the concentration of 2-CP in a single 2-liter sterile control.

Transformation of 2-CP in the sediment slurry reactors resulted in the production of several aromatic metabolites, including phenol and benzoate (Fig. 1B and C). Substantial amounts of a third metabolite, which had a significantly longer retention time than phenol or benzoate, were also detected in the sediment slurry reactors. On the basis of its retention time and absorbance spectrum, the unknown metabolite was identified as 3-chlorobenzoate (3-CB). The concentrations of 3-CB in the duplicate 160-ml reactors are shown in Fig. 1D.

The formation of these aromatic metabolites was not limited to the 2-CP-degrading sediment slurries described here. Significant amounts of phenol, benzoate, and 3-CB were also detected in previous studies involving 2-CP-degrading slurry reactors that were inoculated with anaerobic sediment collected from the Lake Michigan site at various times over a period of two years (1). In addition, trace amounts of a compound with the same retention time and absorbance spectrum as 3-chloro-4-hydroxybenzoate were sporadically detected in the previously studied 2-CP-degrading sediment slurries. None of these aromatic metabolites were ever detected in sterile controls.

The concentrations of phenol, benzoate, and 3-CB followed similar patterns in all of the sediment slurry reactors. In each case, phenol production occurred concomitantly with the removal of the first addition of 2-CP (Fig. 1B). The decline in phenol concentrations was accompanied by the production of benzoate (Fig. 1C). As shown in Fig. 1D, by the time benzoate was no longer detectable in the slurries, some 3-CB had been formed in each of the reactors. Significant production of 3-CB coincided with the biotransformation of the second (160-ml reactors [Fig. 1D]) or third (2-liter reactor [data not shown]) addition of 2-CP.

All of the 2-CP transformed in the duplicate 160-ml reactors within the first 3 weeks of incubation was converted to phenol. This indicates that, initially, all of the 2-CP transformed in the reactors underwent reductive dehalogenation. The concomitant removal of phenol and production of benzoate in the three reactors suggest that the phenol produced by reductive dehalogenation was subsequently biotransformed to benzoate, presumably via sequential carboxylation and dehydroxylation reactions. However, the detection of 3-CB in all three reactors by day 63 (Fig. 1D) indicates that transformation of 2-CP via a second pathway also occurred. The amount of 2-CP transformed via this alternative pathway was significant. The maximum molar ratios of 3-CB accumulated to cumulative 2-CP degraded exceeded 20% in the duplicate 160-ml reactors.

The presence of 3-CB or an alternative 2-CP biotransformation pathway may have decreased the overall rate of 2-CP transformation in some of the reactors. High concentrations of 3-CB persisted in the 160-ml reactors for approximately 60 to 70 days (Fig. 1D). As shown in Fig. 1A, during this period, the biotransformation of 2-CP via reductive dehalogenation or an alternative pathway was severely reduced in the duplicate 160-ml reactors. It is not known whether reductive dehalogenation of 2-CP continued after 63 days in the 160-ml reactors because no phenol was detected in these systems after 49 days (Fig. 1B), and the 3-CB levels did not increase significantly after 63 days (Fig. 1D).

On the other hand, although 3-CB persisted for over 50 days in the 2-liter reactor, the rate of 2-CP transformation was not significantly diminished for an extended period of time (data not shown), as was observed in the 160-ml reactors. Furthermore, low levels of phenol were sporadically detected during periods of increasing 3-CB concentrations in the 2-liter reactor (data not shown), which suggests that simultaneous biotransformation of 2-CP to 3-CB and reductive dehalogenation of 2-CP were feasible.

Removal of 3-CB was observed approximately two to three months after it was produced in the 2-CP-degrading reactors, as illustrated in Fig. 1D. No aromatic metabolites of 3-CB biotransformation were detected in the 2-liter and duplicate 160-ml 2-CP-degrading reactors. However, in a parallel study, benzoate accumulated transiently in dilutions of methanogenic 3-CB-degrading reactors that were inoculated with sediment obtained from the same site in Lake Michigan (1). Therefore, it is likely that 3-CB was biotransformed in the 2-CP-degrading sediment slurry reactors via reductive dehalogenation to benzoate. Presumably, benzoate-degrading populations that had already been established within the 2-CP-degrading community rapidly consumed benzoate produced from the reductive dehalogenation of 3-CB and prevented it from accumulating.

The initial biotransformation of 2-CP via reductive dehalogenation in the sediment slurry reactors was expected on the basis of results of numerous previous studies (e.g., see references 4 and 15). The biotransformation of 2-CP to 3-CB has not been observed frequently. However, a methanogenic consortium that was enriched on phenol and proteose peptone for several years produced 3-CB from 2-CP when the monochlorophenol was added in equimolar amounts with phenol (3). The phenol-degrading consortium also carboxylated other ortho-substituted phenolic compounds in the presence of phenol and the growth substrate, but unlike the methanogenic sediment community evaluated in this study, it did not mediate reductive dehalogenation of 2-CP or biotransformation of 3-CB.

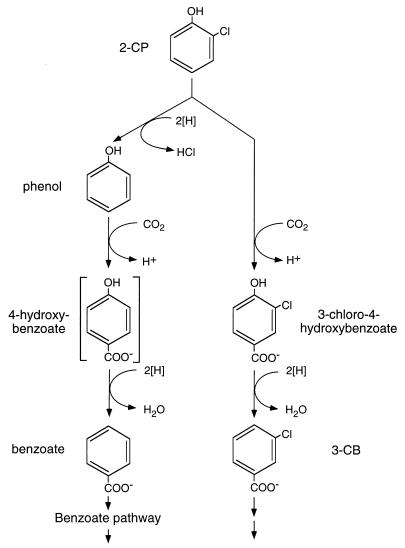

The proposed pathways for 2-CP biotransformation in the sediment slurry reactors are shown in Fig. 2. Reductive dehalogenation of 2-CP to phenol, followed by carboxylation of phenol to 4-hydroxybenzoate and subsequent dehydroxylation to benzoate, is shown on the left side of Fig. 2. 4-Hydroxybenzoate was the only aromatic metabolite that was not detected (UV, A280) in this pathway. However, 4-hydroxybenzoate has also been undetectable in several other studies involving the anaerobic biotransformation of phenol to benzoate (e.g., see reference 20).

FIG. 2.

Proposed pathways for the biotransformation of 2-CP in the anaerobic sediment community.

Biologically mediated reactions that could lead to the production of 3-CB from 2-CP in the sediment slurry reactors are shown on the right side of Fig. 2. In this sequence of reactions, 2-CP is para-carboxylated to produce 3-chloro-4-hydroxybenzoate, which is subsequently dehydroxylated to yield 3-CB. Several observations support this proposed pathway. First, the analogous reactions of carboxylation of phenol to 4-hydroxybenzoate and dehydroxylation of 4-hydroxybenzoate to benzoate occurred in the sediment slurry reactors. Second, trace amounts of a compound with the same retention time and absorbance spectrum as 3-chloro-4-hydroxybenzoate, which is an intermediate in the proposed pathway, were detected sporadically in previously studied 2-CP-degrading slurry reactors that were inoculated with sediment obtained from the same Lake Michigan site (1). Finally, in previous studies conducted by other researchers (16, 17), monofluorophenols were added as phenol analogs to anaerobic phenol-degrading enrichments in order to elucidate the phenol biodegradation pathway. In these studies, 2-fluorophenol was transformed to 3-fluorobenzoate, 2-fluorobenzoate was produced from 3-fluorophenol, and 4-fluorophenol was not transformed. para-Carboxylation followed by dehydroxylation can explain the production of the monofluorobenzoates from 2- and 3-fluorophenol but cannot occur with 4-fluorophenol because the para position is blocked by the fluorine substitute. The biotransformation reactions involving the monofluorophenols (16, 17) and 2-CP (3) in phenol-degrading enrichments demonstrate that carboxylation and subsequent dehydroxylation of a monohalogenated phenol are feasible in other anaerobic communities.

The transformation of 2-CP to 3-CB in the sediment slurry reactors may involve cometabolic reactions. Several observations are consistent with this hypothesis. First, carboxylation and dehydroxylation of phenol to benzoate in an anaerobic coculture that contains the Clostridium-like strain 6 and the gram-positive strain 7 (9) are cometabolic reactions (10). Furthermore, an enzyme that mediates decarboxylation of 4-hydroxybenzoate and the reverse phenol carboxylase activity in Clostridium hydroxybenzoicum, which was isolated from a 2,4-dichlorophenol-degrading freshwater sediment enrichment, also acts on other hydroxylated aromatic compounds (7). 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoate, 3-fluoro-4-hydroxybenzoate, and 3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzoate (vanillate) are decarboxylated by this enzyme. Similarly, the strain 6 reversible 4-hydroxybenzoate decarboxylase also catalyzes the carboxylation of catechol to 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate (11). Thus, the populations that participate in the transformation of phenol and the production of benzoate in the sediment slurry reactors could also conceivably mediate cometabolic transformation of 2-CP to 3-CB. In other words, the production of 3-CB from 2-CP might have been the result of nonspecific, “premature” carboxylation and dehydroxylation reactions.

The results of this study reveal a potential limitation of using anaerobic microbial communities to remove chlorinated phenols. That is, transformation of 2-CP to another chlorinated compound is not acceptable from a treatment standpoint if that chlorinated product is not further degraded. Although the 2-CP-degrading community examined in this study eventually removed 3-CB, this property is not shared by all anaerobic 2-CP-degrading communities (e.g., see reference 15). Furthermore, some of the evidence obtained in this study suggests that 3-CB production may be correlated with reduced 2-CP biotransformation rates. However, the extent to which this transformation occurs in natural and engineered anaerobic environments and the factors that determine whether 2-CP is transformed via reductive dehalogenation or an initial carboxylation reaction are not yet known.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency grant R823351.

We thank Gina Berardesco for obtaining the sediment samples and Brian Wrenn for thoughtful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker J G. Characterization of anaerobic microbial communities that adapt to 3-chlorobenzoate and 2-chlorophenol: an integrated approach of chemical measurements and molecular evaluations. Ph.D. dissertation. Evanston, Ill: Northwestern University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisaillon J-G, Lépine F, Beaudet R, Sylvestre M. Carboxylation of o-cresol by an anaerobic consortium under methanogenic conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2131–2134. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.8.2131-2134.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisaillon J-G, Lépine F, Beaudet R, Sylvestre M. Potential for carboxylation-dehydroxylation of phenolic compounds by a methanogenic consortium. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:642–648. doi: 10.1139/m93-093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd S A, Shelton D R, Berry D, Tiedje J M. Anaerobic biodegradation of phenolic compounds in digested sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:50–54. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.1.50-54.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman D L, Gossett J M. Biological reductive dechlorination of tetrachloroethylene and trichloroethylene to ethylene under methanogenic conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2144–2151. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.9.2144-2151.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elder D J E, Kelly D J. The bacterial degradation of benzoic acid and benzenoid compounds under anaerobic conditions: unifying trends and new perspectives. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;13:441–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He Z, Wiegel J. Purification and characterization of an oxygen-sensitive reversible 4-hydroxybenzoate decarboxylase from Clostridium hydroxybenzoicum. Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heider J, Fuchs G. Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:577–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Letowski J, Villemur R, Bisaillon J-G, Beaudet R, Lépine F. Abstracts of the 98th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1998. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Study of an anaerobic phenol transforming syntrophic coculture of two new species of bacteria, abstr. Q-79; p. 434. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li T, Bisaillon J-G, Villemur R, Létourneau L, Bernard K, Lépine F, Beaudet R. Isolation and characterization of a new bacterium carboxylating phenol to benzoic acid under anaerobic conditions. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2551–2558. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2551-2558.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li T, Bisaillon J-G, Beaudet R. Abstracts of the 98th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1998. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Purification and characterization of 4-hydroxybenzoate decarboxylase from a new species of Clostridium, abstr. Q-80; p. 434. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Londry K L, Fedorak P M. Use of fluorinated compounds to detect aromatic metabolites from m-cresol in a methanogenic consortium: evidence for a demethylation reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2229–2238. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2229-2238.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller T L, Wolin M J. A serum bottle modification of the Hungate technique for cultivating obligate anaerobes. Appl Microbiol. 1974;27:985–987. doi: 10.1128/am.27.5.985-987.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohn W W, Tiedje J M. Microbial reductive dehalogenation. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:482–507. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.482-507.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharak Genthner B R, Price II W A, Pritchard P H. Characterization of anaerobic dechlorinating consortia derived from aquatic sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1472–1476. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.6.1472-1476.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharak Genthner B R, Townsend G T, Chapman P J. Anaerobic transformation of phenol to benzoate via para-carboxylation: use of fluorinated analogues to elucidate the mechanism of transformation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;162:945–951. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)90764-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharak Genthner B R, Townsend G T, Chapman P J. Effect of fluorinated analogues of phenol and hydroxybenzoates on the anaerobic transformation of phenol to benzoate. Biodegradation. 1990;1:65–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00117052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharak Genthner B R, Townsend G T, Chapman P J. para-Hydroxybenzoate as an intermediate in the anaerobic transformation of phenol to benzoate. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;78:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90168-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suflita J M, Townsend G T. The microbial ecology and physiology of aryl dehalogenation reactions and implications for bioremediation. In: Young L Y, Cerniglia C E, editors. Microbial transformation and degradation of toxic organic chemicals. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1995. pp. 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Wiegel J. Sequential anaerobic degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenol in freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1119–1127. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.4.1119-1127.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Wiegel J. Reversible conversion of 4-hydroxybenzoate and phenol by Clostridium hydroxybenzoicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4182–4185. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.4182-4185.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Young L Y. Carboxylation as an initial reaction in the anaerobic metabolism of naphthalene and phenanthrene by sulfidogenic consortia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4759–4764. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4759-4764.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]