Abstract

Introduction:

Retired plastic surgeons can provide valuable insights for the greater plastic surgery community. The purpose of this study was to gather demographics, personal reflections, and advice for a career in plastic surgery from retired American plastic surgeons.

Methods:

An email survey was distributed to 825 members of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons during September 2021. The survey distribution was designed to engage members of the plastic surgery community, who were retired from surgical practice in the United States. The form consisted of 29 questions, five of which were free response. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed.

Results:

A total of 214 completed surveys were received, with a response rate of 25.9%. The average age at retirement was 67.6 years. The majority of respondents were men (87.6%) and White (93.3%); 46.9% of surgeons practiced at individual private practice. Ninety percent of surgeons indicated that they would choose to practice as a plastic surgeon again. Free responses provided positive career reflections and advice for young plastic surgeons regarding navigating the changing landscape of healthcare.

Conclusions:

Retired plastic surgeons are interested in engaging with the plastic surgery community and demonstrate continued interest in the future of the field. Efforts can be made to avail the field of their expertise and experience.

Takeaways

Question: What can we learn from surveying retired American plastic surgeons regarding their personal reflections and practice advice for a career in plastic surgery?

Findings: From a survey conducted with the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, this study reports the personal demographics and practice details for a group of over 200 American plastic surgeons who have retired from full-time practice in plastic surgery. Additionally, the surgeons’ reflections (best career decisions, challenges, and advice for early-career surgeons) on their careers in plastic surgery are detailed.

Meaning: From the survey results, it is clear that retired plastic surgeons provide valuable insights and are interested in engaging further with the plastic surgery community.

INTRODUCTION

As the nature of medical and surgical practice changes rapidly, plastic surgery adapts to meet the challenges. However, innovation in research, clinical technique, and leadership does not always stem from new and undiscovered areas. By learning from and about the past, the plastic surgery community can rediscover existing strategies that might help address practice- and system-wide struggles that many surgeons find themselves facing today. To access that perspective, we can look to an incredibly valuable and largely untapped resource: retired plastic surgeons.

Senior and retired plastic surgeons are honored and remembered in many ways—the field of plastic surgery has this rich tradition.1–3 However, although it is edifying to highlight influential surgeons and their groundbreaking contributions to the specialty, there are additionally many more thousands of plastic surgeons who have accumulated a wealth of specialty- and practice-specific knowledge that can strengthen the field.4 Although difficult to present what is cumulatively thousands of years of practice without losing significant detail and nuance, there is a need to expand this institutional memory to persevere progress. The resulting quantitative and qualitative data can help inform individual surgeons, academic programs, and national organizations to better equip the workforce as the field evolves within the current healthcare landscape.

To that end, this study presents the results of a national survey conducted with the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) to further understand the practice and career reflections of plastic surgeons who have retired from full-time surgical practice. The aim of this study was to characterize the demographic makeup of the group of retired surgeons (many of whom entered surgical practice in the 1970s) and catalog their experiences both qualitatively and quantitatively. The findings will help form the basis of future initiatives to connect the plastic surgery community with retired plastic surgeons, who have much to offer in the way of surgical technique, practice management, and general career advice.

METHODS

This study was deemed IRB exempt by the study hospital institutional review board. Participation was completely voluntary, the privacy of the participants was protected, and the confidentiality of individual survey respondents’ identities was maintained. A survey querying plastic surgeons who have retired from full-time surgical practice for their career reflections and advice for practicing plastic surgeons was distributed to 825 retired plastic surgeons in the United States. Surveys were administered in a single electronic mailing via selected ASPS mailing lists. ASPS professional society members include both private practice and academic plastic surgeons practicing across the United States. Surveys were initially sent on August 31, 2021, and responses were collected through October 2021. Three reminders were sent on September 3, September 11, and September 23, 2021, respectively.

A total of 29 questions were asked to delineate information regarding (1) personal demographics, (2) training, (3) clinical practice, (4) family life, (5) practice and personal finance, and (6) general career advice. The survey was designed by the research team and approved by the senior author (B.T.L.). These questions collected a variety of response formats, including yes/no, multiple choice, and free text.

The collected answers were imported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Wash.) for qualitative and statistical analysis. Partially completed surveys were included in the final analysis to the greatest extent possible. For questions with free text responses, equivalent phrases and statements were identified within the body of the response and counted as the same answer to simplify the assessment of results and understand overarching qualitative categorical themes. Descriptive statistical analyses, including frequencies, measures of central tendencies, and measures of variability, were performed using Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS

A total of 214 surveys were returned, representing a 25.9% response rate from the 825 plastic surgeons who were invited to complete the survey based on their self-description of employment status. Two-hundred ten invited plastic surgeons (98%) confirmed that they were retired from full-time surgical practice or were within 1 year of retirement. A nonresponder analysis is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Retired Plastic Surgeons: Personal Characteristics

| Retired Plastic Surgeons Survey Respondents: Personal Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Time, median (IQR) in years | |

| Age at the time of survey: September 2021 | 75 (70–79) |

| Age at the time of Retirement | 68 (64–72) |

| Age at the start of plastic surgery practice | 34 (32–35) |

| Length of career | 34 (30–39) |

| Gender, % (n) | |

| Men | 87.6 (170) |

| Women | 11.3 (22) |

| Prefer not to say | 1.0 (2) |

| Race, % (n) | |

| White | 93.3 (180) |

| Asian | 3.6 (7) |

| Hispanic | 0.5 (1) |

| Prefer not to say | 1.6 (3) |

| Other | 1.0 (2) |

| Practice location, % (n) | |

| Northeast (NJ, NY, PA, RI, CT, MA, VT, NH, and ME) | 19.6 (38) |

| South (MD, DE, WV, VA, DC, KY, TN, NC, SC, GA, AL, MS, FL AR, LA, OK, and TX) | 32.5 (63) |

| Midwest (OH, MI, IN, WI, IL, MN, IA, MO, ND, SD, NE, and KS) | 18.6 (36) |

| West (MT, WY, CO, NM, ID, UT, AZ, WA, OR, CA, and NV) | 27.8 (54) |

| Pacific (AK and HI) | 1.0 (2) |

| Prefer not to say | 0.5 (1) |

| Practice type, % (n) | |

| Individual practice (private) | 46.9 (91) |

| Group practice (private) | 23.7 (46) |

| Academic practice | 10.3 (20) |

| Combined academic/private practice | 13.4 (26) |

| Other | 5.7 (11) |

IQR (Q1, Q3).

Demographics

The average age of plastic surgeon respondents was 74.5 years (range, 60–91). The average age of retirement was 67.6 years (range, 45–86 years). The majority of respondents are men (87.6%) and 11.3% are women. With regard to ethnic makeup of respondents, 93.3% self-identified as White, 3.6% as Asian, and 0.5% as Hispanic. Regarding geographic region where respondents practiced plastic surgery for the longest duration, 32.5% named the Southern United States; 27.8% the West; 19.6% the Northeast; 18.6% the Midwest; and 1% replied that they had practiced in the Pacific (Alaska or Hawaii) the longest (Table 2). Demographic information is represented pictorially in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Retired Plastic Surgeons: Leadership Roles

| Retired Plastic Surgeons Survey Respondents: Leadership Roles, % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Practice owner | 61.4 (108) |

| Section chief/department chair | 54.6 (96) |

| University professor | 39.2 (69) |

| Society/organization president | 27.8 (49) |

| Principal investigator (research) | 24.4 (43) |

| Residency program director | 17.1 (30) |

| Journal editor | 4.6 (8) |

| Other | 21.6 (38) |

Fig. 1.

Retired plastic surgeons: demographics. Selected demographics of responding retired plastic surgeons.

Training

The average age for plastic surgery residency or fellowship graduation was 34 years (range, 29–45 years). An estimated 83.5% of respondents noted that their training pathway consisted of general surgery residency training followed by a plastic surgery residency (independent plastic surgery training). Of the respondents, 9.8% trained through an integrated plastic surgery residency model. In total, 6.7% replied that they had trained in another surgical subspecialty (otolaryngology, orthopedic surgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery, or neurosurgery) and then completed a plastic surgery residency.

With regard to fellowship training, 72.2% of retired plastic surgeons did not pursue fellowship training after residency and 27.8% did complete a fellowship. Of those who completed fellowship training, the most common area of subspecialist training was craniofacial surgery (34.0%). Training information is further presented in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Retired plastic surgeons: training. Selected training and early-career information reported by retired plastic surgeons.

Career

When asked about the practice environments they had operated in for the longest amount of time, 46.9% of retired plastic surgeons practiced in a private, single-surgeon (ie, “solo”) practice setting, 23.7% in private group practice, 13.4% in combined academic and private practice, and 10.3% reported practicing primarily in an academic setting. Slightly over half of respondents (51.8%) indicated that their practice was best described as general plastic surgery (no subspecialization), whereas 19.4% replied that they had practiced mostly in aesthetic plastic surgery (Fig. 3). When asked about leadership roles held during their careers, 83.8% indicated that they had held at least one position in leadership during their career. Of these, 61.4% indicated that they had owned a plastic surgery practice, and 54.5% reported that they had served as either section chief or department chair (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Retired plastic surgeons: career. Selected practice details reported by retired plastic surgeons.

Table 3.

Retired Plastic Surgeons Survey: Nonresponder Analysis

| Retired Plastic Surgeons Survey Nonresponder Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Survey Population | Survey Responders | Survey Nonresponders | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 84 (10) | 23 (11) | 61 (10) |

| Male | 736 (90) | 191 (89) | 545 (90) |

| Age, n (%) | |||

| 55–64 | 47 (6) | 13 (6) | 34 (6) |

| 65 and over | 770 (94) | 201 (94) | 569 (94) |

| Practice makeup, n (%) | |||

| 100% reconstructive | 53 (11) | 21 (15) | 32 (9) |

| 75% reconstructive/25% cosmetic | 111 (22) | 30 (22) | 81 (22) |

| 50% reconstructive/50% cosmetic | 104 (21) | 24 (18) | 80 (22) |

| 25% reconstructive/75% cosmetic | 122 (24) | 28 (21) | 94 (26) |

| 100% cosmetic | 110 (22) | 33 (24) | 77 (21) |

Ninety percent of retired surgeons affirmed they would choose to practice as a plastic surgeon again. Of the 10.0% who would not have chosen to practice as a plastic surgeon again, 57.1% replied that they would have chosen to practice in a different medical specialty (most commonly, orthopedic surgery), and 42.9% would have chosen an entirely nonmedical career.

Family

When asked about their family life, 72.3% of respondents reported that they are currently married, whereas 2.6% responded they had never married. Of those who are married, 73.0% reported that their spouse did work outside the home during their careers. In total, 92.1% of surgeons reported that they had children, and of those, 91.4% had two or more children (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Retired plastic surgeons: family. Selected family makeup reported by retired plastic surgeons.

Finances

Of the retired surgeons, 94.1% affirmed that a career in plastic surgery afforded them enough financial stability for their retirement. In the free responses accompanying this question, surgeons described how they had achieved this, with the most common themes including prioritizing saving for retirement from the first day of independent practice, and learning business administration and practice management skills.

Reflections: Qualitative Results

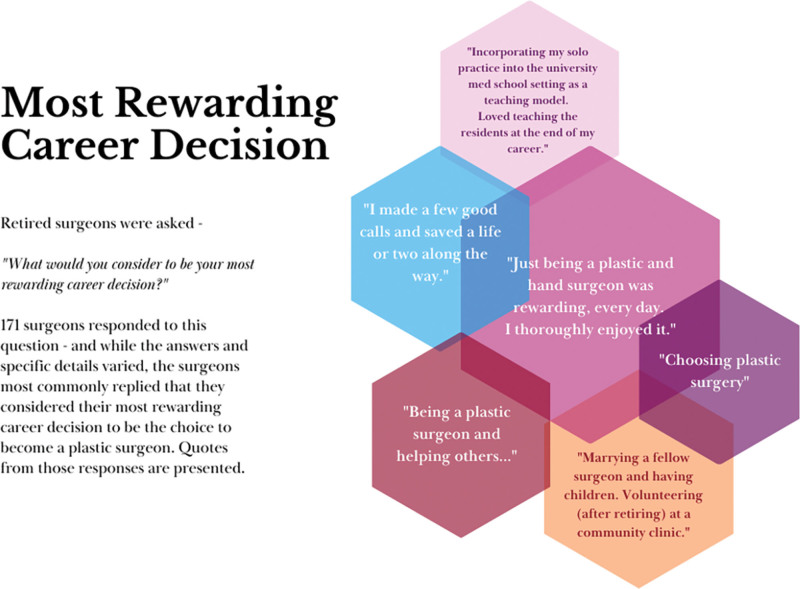

Surgeons were asked five short-answer questions to capture career reflections that they believed might be helpful to share with the plastic surgery community. The first of these questions was “what would you consider to be your most rewarding career decision?” which was answered by 79.9% (171) of respondents. A variety of responses were given for this question; however, the most common response had the theme of “choosing to practice as a plastic surgeon” (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Most rewarding career decisions: selected quotes.

The second free response question asked was “what was the greatest professional or personal challenge you faced as a plastic surgeon?” which was answered by 79.9% (171) of respondents. Again, responses were heterogeneous, but the most common responses focused on themes of administrative and practice management difficulties (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Greatest professional challenges.

The third free response question posed to the retired surgeons was “would you have done anything differently in your life or career as a plastic surgeon?” The most common response to this question was “no.” This question was answered by 82.2% (176) of respondents.

The fourth question asked was “in your opinion, do you think that young plastic surgeons at the start of their careers will have the same opportunities afforded to you when you started your career? Do you feel they will have an easier or harder time?” This question was answered by 78.0% (167) respondents. The most common response theme from the retired plastic surgeons was that they believed early-career plastic surgeons would have a harder time in practice and experience less opportunities than they did due to challenges posed by the increasing corporatization of American healthcare.

The fifth and final question posed to the retired plastic surgeons was if they had any specific, actionable advice for early-career plastic surgeons and/or trainees. This question was answered by 73.8% (158) respondents. Responses varied in content and specificity. The most common advice recommended was prioritizing patient safety and developing a durable work ethic early in practice.

DISCUSSION

There are thousands of retired plastic surgeons who have practiced for many decades—they have seen changing political regimes, technological advances, and evolutions in healthcare; they are able to provide the plastic surgery community with hard-earned insight from their careers and lives.5 Previous studies have surveyed senior practicing surgeons and characterized their practice patterns and retirement plans in an effort to help create and steward resources to strengthen the community of plastic surgeons.6 This study aims to add to that effort by characterizing the group of retired plastic surgeons and surveying them for their advice to drive the future of the profession.

The main quantitative findings of this study demonstrate the demographics of this group of retired surgeons comprising mostly men, and those having completed general surgery training before plastic surgery training and having experienced a “general plastic surgery” mix instead of early specialization. These trends are largely unsurprising given the historical plastic surgery training pathway. When considering the particulars of the qualitative responses provided, it is important to understand the context of the specialty and the medical community at the time. Nevertheless, many significant themes arise that can be used to plan future specialty-wide initiatives in education, political involvement, and healthcare leadership.

From both the qualitative and quantitative responses, it was clear that the vast majority, 90%, of responding plastic surgeons experienced a high level of career satisfaction. These findings are slightly higher than those of a previous study, demonstrating that approximately three-fourths of practicing plastic surgeons are satisfied with their career choice.7 Recalling that the survey’s overall response rate was roughly 25%, there is potential concern for response bias—that is, nonresponding surgeons may have declined to respond due to career dissatisfaction. However, there are a few elements that make this less likely: the language in the survey email did not mention career satisfaction and instead used the phrase “career reflection”; the questions ascertaining career satisfaction were phrased obliquely (eg, “would you choose to practice as a plastic surgeon again?”); and many surgeons, while indicating that they would or would not choose to practice as a plastic surgeon again, reflected frankly on both their negative and positive experiences. Additionally, the nonresponder analysis illustrates that personal and practice demographics of responders and nonresponders are similar. Although this does not completely eliminate the possibility of response bias, it is much more likely that the relatively low response rate could be attributed to a different phenomenon, such as the survey’s electronic format, as opposed to a deliberate abstention from answering questions regarding career satisfaction.

Of the 10% of retired surgeons who indicated that they would have chosen a career path other than plastic surgery, over half expressed that they would have specialized in orthopedic surgery instead of plastic surgery. The reasons provided were specific to the surgeon answering, but most had to do with the case makeup they anticipated they would have experienced in orthopedic surgery versus that of plastic surgery. Many of these surgeons’ practices were completely reconstructive, with specialization in hand surgery. Through that practice type, the surgeons worked alongside orthopedic surgeons and were able to experience that specialty, firsthand. However, even within this group of surgeons who expressed that they would have rather specialized in a different branch of surgery or medicine, many still expressed an overall satisfaction with their plastic surgery careers, patients, and choices.

Of those who would have chosen a career entirely outside of medicine, the most common reasoning provided for this was the unwieldy administrative and legal burdens placed on surgeons in the increasingly corporatized healthcare landscape. They cited that this occurrence prevented them from enjoying the practice of surgery and medicine. Although others indicated that these corporate trends did not weigh as heavily for them, a common theme of concern for many surgeons was the increasing role of corporate influence and interference in the practice of medicine. This administrative trend, they said, has coincided with a general decline in reimbursements for reconstructive procedures and increase in “competition” from cosmetic surgery practitioners who are not certified by the American Board of Plastic Surgery. Some indicated that these issues, compounded by the devastation of the global COVID-19 pandemic, hastened their choice to retire.

Now, many surgeons cited these issues—corporate influence, declining reimbursements, and increased competition—as the major challenges that plastic surgery practice young surgeons would encounter and be forced to either surmount or submit, and some offered general reflections and actionable advice to help plastic surgeons protect their patients and their autonomy. Different responses distilled the healthcare landscape; thus the current model would push surgeons toward a more “9–5” existence with a greater focus on work-life balance, but would also strip them of the freedom to build and shape their practice to their liking. These events may also come with increased productivity demands from administrators that may, at times, be incongruent with the practice of safe surgery that prioritizes patient protection. To circumvent this, surgeons recommended joining practice groups with surgeon leadership and becoming more familiar with the financial and administrative aspects of healthcare. Most advocated for complete honesty with patients, and for building a practice around the individual surgeon’s talents. Beyond advice for weathering administration and management, the most common advice for all surgeons was to find mentors that one admired for their work ethic, technical ability, and integrity in patient and practice dealings.

Although this study aimed to contribute to the plastic surgery literature, it has several limitations that can be addressed in further studies and initiatives. The first of these limitations is the relatively low response rate; it is unclear whether this rate is due to the format of the survey (electronic, sent via email), the timing of the survey (sent midlate summer), or a general lack of interest in responding to this survey. Further research should be done to determine how to best connect with retired surgeons who are interested in similar efforts. It may be worthwhile to offer the surveys in more than one medium, such as via phone call or mailed paper form, in addition to providing an electronic option, as has been done in analogous studies involving this generation of physicians.8 Another significant limitation of this study lies in the presentation of details within the confines of this article. The free responses provided by the plastic surgeons are brief, which potentially miss both nuance and contextualization as they are presented here. Due to the nature of reporting findings in a standard article format, these hundreds of responses are unable to be described here to their full effect. Although this finding seems to be a byproduct of the format of reporting these results, more work needs to be done to present these pieces of advice in a way that is useful to the plastic surgery community. A final limitation is that although many surgeons were happy to answer the predetermined questions and offer generalized advice, the most useful advice would be customized to both the adviser and advisee’s specific situations and questions. For example, the survey did not include any questions asking for causes of burnout or other reasons that might have led to the decision to retire from full-time practice. This would be interesting information that could help corroborate related studies on the topic and provide insight into retirement decisions for senior surgeons. It follows that there is no such thing as “one-size-fits-all” mentoring or career planning, as every surgeon and trainee holds different perspectives and circumstances, and therefore, the advice given is not generalizable to every member of the plastic surgery community.

The results of this survey prove that there is much more to learn from retired surgeons. Involving these surgeons in academic and societal efforts would greatly help strengthen and fortify the plastic surgery community.9 As many of the retired surgeons expressed a desire to remain involved in the active plastic surgery community, and specifically the academic community that consists of students, residents, and fellows, there is perhaps an opportunity to formalize their involvement. Although structured, mandated mentorship programs often do not appeal to either mentor or mentee, providing an established avenue for retired surgeons to connect with trainees or established plastic surgeons may be of significant benefit to all who participate. Additionally, consideration and inspiration may be taken from our general surgery colleagues, who are investigating and piloting the concept of “surgical coaching” wherein senior surgeons are able to instruct and advise junior surgeons on clinical and nonclinical skills important to surgical practice.10 There is also interest in career planning and retirement planning for plastic surgeons at all levels of practice; retired surgeons could certainly provide helpful perspective to this end.11,12 Although these ideas ultimately require buy-in from all parties involved, this study clearly demonstrates that there are many retired surgeons who are amenable to effective, efficient channels of connection and idea exchange with the greater plastic surgery community.

CONCLUSIONS

This study aims to help start building a framework for a tradition of intergenerational knowledge transfer in plastic surgery. As the challenges to career planning, establishment, and success become increasingly difficult to navigate within a complicated, ever-evolving healthcare landscape, every medical specialty would benefit from a thorough understanding of where the field has been to help shape the future in specific, actionable ways.

Footnotes

Published online 6 June 2022.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morain WD. History and plastic surgery: systems of recovering our past. Clin Plast Surg. 1983;10:595–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stark RB. The history of plastic surgery in wartime. Clin Plast Surg. 1975;2:509–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ICON project. The American Association of Plastic Surgeons: the ICON Project. Accessed at https://aaps1921.org/Icon/. Accessed November 10, 2021.

- 4.Asserson DB, Janis JE. The aging surgeon: evidence and experience. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohan Rao M. A plastic surgeon retires. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:721–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohrich RJ, McGrath MH, Lawrence TW; ASPS Plastic Surgery Workforce Task Force and AAMC Center for Workforce Studies . Plastic surgeons over 50: practice patterns, satisfaction, and retirement plans. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1458–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Streu R, Hawley S, Gay A, et al. Satisfaction with career choice among U.S. plastic surgeons: results from a national survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:636–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolarski A, Moseley JM, O’Neal P, et al. Retired surgeons’ reflections on their careers. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:359–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Benna S. Retired plastic surgeons as educators during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020;44:2326–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg CC, Byrnes ME, Engler TA, et al. Association of a statewide surgical coaching program with clinical outcomes and surgeon perceptions. Ann Surg. 2021;273:1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carbullido MK, Hornacek M, Reid CM, et al. Career development in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147:1441–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson DJ, Shenaq D, Thakor M. Making the end as good as the beginning: financial planning and retirement for women plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]