Abstract

Despite the mental health and substance use burden among people living with HIV (PLHIV) in the Asia–Pacific, data on their associations with HIV clinical outcomes are limited. This cross-sectional study of PLHIV at five sites assessed depression and substance use using PHQ-9 and ASSIST. Among 864 participants, 88% were male, median age was 39 years, 97% were on ART, 67% had an HIV viral load available and < 1000 copies/mL, 19% had moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms, and 80% had ever used at least one substance. Younger age, lower income, and suboptimal ART adherence were associated with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms. Moderate-to-high risk substance use, found in 62% of users, was associated with younger age, being male, previous stressors, and suboptimal adherence. Our findings highlight the need for improved access to mental health and substance use services in HIV clinical settings.

Keywords: HIV, Asia, Depression, Substance use, ART adherence

Introduction

In 2020, the Asia–Pacific region was home to 5.8 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) [1]. In the era of effective combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), with increasing rates of ART coverage and virologic suppression, attention has shifted towards the management of HIV as a chronic disease and the need to better address comorbid conditions among PLHIV [2]. Continued HIV treatment cascade gains and reaching the UNAIDS ‘95–95–95’ targets (95% of PLHIV diagnosed, 95% initiating ART, and 95% achieving virologic suppression by 2030) will not be achieved without addressing mental health and substance use disorders among PLHIV [3].

The burden of mental health disorders and substance use among adult PLHIV is high and rates are often higher than those among HIV-negative counterparts [4–6]. Mental health disorders and use of certain substances are also associated with a higher risk of mortality among adult PLHIV [7–9]. Research among adult PLHIV cohorts, predominantly in developed countries, indicate that mental health and substance use disorders are associated with negative HIV clinical and treatment outcomes, such as poorer ART adherence and retention in care, and virologic failure [10–15]. However, similar evidence from the Asia–Pacific region is sparse.

Studies of depression among different adult PLHIV populations in the Asia–Pacific region indicate a prevalence of between 3 and 60% depending on the study population, study methodology, and screening tool used [16–21]. Data on the prevalence of substance use disorders among adult PLHIV in the region have often focused on opiate use in countries where it has historically driven local HIV epidemics, with more limited data on other substance use, such as amphetamines, sedatives and cannabis. Addressing the substantial mental health and substance use burden among PLHIV in the region would also have to be achieved in the context of persistent underfunding and scarcity of human resources for mental health services in the Asia–Pacific region [22]. We therefore conducted a cross-sectional study of depression and substance use among adult PLHIV under care at five HIV clinical centers in the Asia–Pacific region, and assessed risk factors for recent depression and substance use.

Methods

Study Design and Study Population

Adults living with HIV aged 18 years or older and under care at five sites were eligible to participate in this cross-sectional study. Participating sites are all tertiary care centers located in the following urban areas: Hong Kong SAR, China; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; Muntinlupa City, Metro Manila, Philippines; Seoul, South Korea; and Bangkok, Thailand. All study participants were consented and enrolled as they attended routine HIV clinical visits between July 2019 and June 2020.

Data Collection

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to assess for depression over the past two weeks [23], and the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST v3.1) was used to assess ever using a substance, substance use in the past three months, and substance use risk [24]. If available, locally validated versions of PHQ-9 and ASSIST v3.1were used. If validated versions were not available, these screening tools were translated and reviewed by local investigators with related clinical or research experience. In one participating site a cultural adaptation process was developed that included a combination of translation, expert review, and local testing. Data on employment, household income, education level, HIV disclosure status, recent traumatic events or stressors, and family history of mental health diagnoses were collected as part of a study-specific questionnaire. PHQ-9 and ASSIST screenings were conducted by trained study staff or self-administered using electronic tablets. Positive screening results triggered clinical follow-up according to local standards of care, including urgent referrals of participants with suicidal thoughts for further psychiatric assessment and management.

Demographic data (i.e., age, sex, ethnicity, marital status), medical history (i.e., comorbid chronic conditions, sexually transmitted infections), laboratory data (i.e., weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, complete blood count, lipid profile, liver function tests, glucose, creatinine, hepatitis serology), and HIV clinical data (i.e., HIV exposure category, date of HIV diagnosis, history of CDC stage C illness, CD4 cell count, HIV viral load, ART regimen, adverse events, adherence) were collected from existing medical records, as available. We collected all available CD4 cell count and HIV viral load test results for study participants up to the date of their last clinic visit, and Visual Analog Scale adherence assessments from the 12 months preceding the start of this study.

Statistical Analyses

We conducted risk factor analyses to assess associations with the following outcomes: (i) moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms; and (ii) moderate-to-high risk substance use of any drug. Patients were classified as having moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms if they had a PHQ-9 total score of 10 to 27. Moderate-to-high risk substance use was classified as having an ASSIST score ≥ 11 for alcohol or an ASSIST score ≥ 4 for other substances.

Patients with missing questionnaire responses to PHQ-9 and ASSIST were included in the analysis with missing responses imputed using the “hot deck” imputation method [25]. This imputation method replaces the missing value with a single data point imputed from randomly selected patients with complete dataset, who have similar characteristics to those with missing responses. The method was applied consistently across all other questionnaires within the study that required calculations of survey scores.

To account for heterogeneity across sites, we adjusted for World Bank country income grouping in all analyses. Logistic regression was used to analyse factors associated with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms, and moderate-to-high risk substance use. Covariates included were demographics and HIV clinical characteristics, as well as socio-economic risk factors on education, employment, household income, and previous life stressors obtained from the study-specific questionnaire. Not reported or unknown values were included in the regression as a separate category. Regression analyses were fitted using backward stepwise selection process. Covariates with p < 0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. Covariates with p < 0.05 in the multivariate regression model were considered statistically significant.

Data management and statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata software version 16.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical Considerations

All participating study sites, the study coordinating center (TREAT Asia, amfAR/The Foundation for AIDS Research, Thailand), and the data management center (The Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales, Australia) obtained institutional review board (IRB) approvals for study participation. Study participants were consented using standard informed consent and study information forms.

Results

A total of 864 patients participated in the study (Table 1). Of the 864 study participants, 793 (92%) had at least a high school education, 622 (72%) were in full- or part-time employment, and 334 (39%) were from high income countries. Their median age at enrolment was 39 years (IQR 31–47), 758 (88%) were male, 460 (53%) acquired HIV through male-to-male sex, and 841 (97%) were on ART. Among those on ART, median duration of ART was 6 years (IQR 2–11).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Total patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Total | 864 (100) |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |

| Age at study assessment (years) | Median = 39, IQR (31–47) |

| ≤ 30 | 203 (24) |

| 31–40 | 270 (31) |

| 41–50 | 255 (30) |

| > 50 | 136 (16) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 758 (88) |

| Female | 106 (12) |

| Employment status | |

| No | 180 (21) |

| Yes, full-time | 499 (58) |

| Yes, part-time, or occasionally | 123 (14) |

| No response/not reported | 62 (7) |

| Total household income | |

| ≤ 500 USD/local currency equivalent per month | 212 (24) |

| 501–2000 USD/local currency equivalent per month | 258 (30) |

| > 2000 USD/local currency equivalent per month | 257 (30) |

| No response/unknown/not reported | 137 (16) |

| Highest education level | |

| No formal education | 4 (0) |

| Primary school | 46 (5) |

| High school | 231 (27) |

| College/vocational training | 125 (14) |

| University | 437 (51) |

| No response/not reported | 21 (2) |

| HIV-related characteristics | |

| HIV mode of exposure | |

| Heterosexual contact | 276 (32) |

| MSM | 460 (53) |

| Injecting drug use | 15 (2) |

| Other/Unknown | 113 (13) |

| Year of ART initiation | |

| < 2010 | 236 (27) |

| 2010–2012 | 115 (13) |

| 2013–2015 | 189 (22) |

| 2016–2020 | 313 (36) |

| No ART/unknown | 11 (1) |

| Viral Load at study assessment (copies/mL) | Median = 33, IQR (19–39) |

| < 50 | 535 (62) |

| 50–399 | 37 (4) |

| 400–999 | 4 (0.5) |

| ≥ 1000 | 49 (6) |

| Not tested | 239 (28) |

| Median (IQR) viral load among those with VL ≥ 1000 (copies/mL) |

107,644 (IQR 45,556–406,000) |

| CD4 at study assessment (cells/µL) | Median = 519, IQR (333–725) |

| ≤ 200 | 73 (8) |

| 201–350 | 94 (11) |

| 351–500 | 123 (14) |

| > 500 | 319 (37) |

| Not tested | 255 (30) |

| Current ART | |

| NRTI + NNRTI | 455 (53) |

| NRTI + PI | 55 (6) |

| INSTI | 320 (37) |

| Other | 11 (1) |

| None/unknown | 23 (3) |

| ART adverse events in the previous year | |

| No | 603 (70) |

| Yes | 93 (11) |

| Not reported/unknown | 168 (19) |

| ART adherence in the previous year | |

| ≥ 95 | 566 (66) |

| < 95 | 58 (7) |

| Not reported/unknown | 240 (28) |

| Prior AIDS diagnosis | |

| No | 556 (64) |

| Yes | 202 (23) |

| Not reported | 106 (12) |

| Disclosure of HIV status | |

| Full (i.e. to all friends and family) | 41 (5) |

| Partial (i.e. to some friends or family) | 617 (71) |

| None, to no one | 162 (19) |

| No response/ not reported/ unknown | 44 (5) |

| Coinfections, comorbidities and medical history | |

| Hepatitis B co-infection | |

| Negative | 297 (34) |

| Positive | 34 (4) |

| Not tested | 533 (62) |

| Hepatitis C co-infection | |

| Negative | 410 (47) |

| Positive | 30 (3) |

| Not tested | 424 (49) |

| History of STIs in the past 5 years | |

| No | 413 (48) |

| Yes | 263 (30) |

| Not reported/unknown | 188 (22) |

| Current chronic comorbid condition | |

| No | 352 (41) |

| Yes | 150 (17) |

| Not reported/unknown | 362 (42) |

| Previous mental health diagnosis | |

| No | 639 (74) |

| Yes | 67 (8) |

| Not reported/unknown | 158 (18) |

| Family history of mental health diagnoses | |

| No | 739 (86) |

| Yes | 34 (4) |

| Not reported/unknown | 91 (10) |

| Traumatic events or stressors experienced in the past 5 years (multiple answers allowed) | |

| None | 389 (45) |

| Unknown | 46 (5) |

| Sexual assault or abuse | 32 (4) |

| Physical assault or abuse | 33 (4) |

| Physical pain or injury e.g. car accident, burns, dog attack | 63 (7) |

| Major surgery or life-threatening illness | 75 (9) |

| Natural disaster e.g. hurricane, flood, fire or earthquake | 36 (4) |

| War or political violence (civil war, terrorism, refugee) | 14 (2) |

| Death of family member, partner or friend | 168 (19) |

| Divorce or separation from a partner | 37 (4) |

| Unemployment, redundancy or significant financial concerns | 190 (22) |

| Home relocation | 90 (10) |

| Arrest or prison stay | 14 (2) |

| Other | 33 (4) |

| Not reported | 24 (3) |

ART antiretroviral therapy, STIs sexually transmitted infections, MSM men who have sex with men, NRTI nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, NNRTI non-NRTI, PI protease inhibitors, INSTI integrase inhibitors, USD US dollars

Of the 609 participants with a CD4 measurement available, median CD4 cell count was 519 cells/µL (IQR 333–725). Of the 625 participants with an available VL within six months of the study assessment, 576 (92%) had VL < 1000 copies/mL. Current ART regimens were nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) plus non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) in 455 (53%), integrase inhibitors (INSTI) in 320 (37%), and NRTI plus protease inhibitors (PI) in 55 (6%). Overall, 639 (74%) had no previous mental health diagnosis, and 389 (45%) had experienced no traumatic event or stressors in the past five years.

Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms

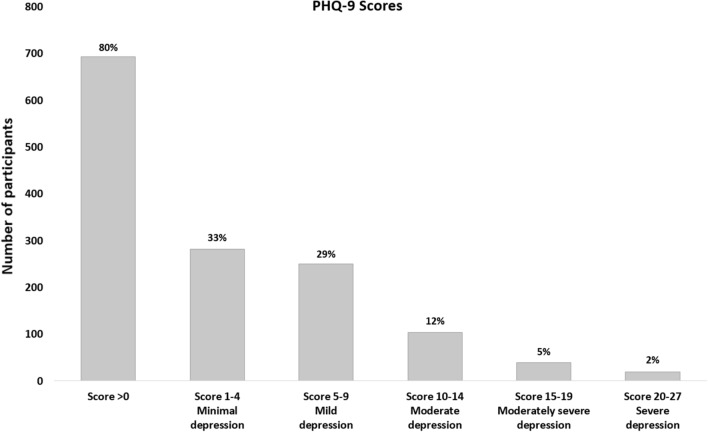

On depression screening, 693 (80%) had a total PHQ-9 score above 0 (95% CI 77–83). There were 282 (33%) participants with minimal depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score 1–4), 250 (29%) with mild depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score 5–9), 103 (12%) with moderate depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score 10–14), 39 (5%) with moderately severe depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score 15–19), and 19 (2%) with severe depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score 20–27) (Fig. 1). Suicidal thoughts on at least several days over the past two weeks were reported in 164 (19%) participants as indicated by a PHQ-9 question 9 score of 1 or above.

Fig. 1.

PHQ-9 scores and severity classification of study participants (N = 864)

Factors Associated with Depressive Symptoms

Overall, 161 (19%) reported moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms, and associated risk factors are shown in Table 2. In the multivariate analysis, moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms were less likely in patients with older age at time of study assessment (41–50 years: aOR = 0.39, 95% CI 0.23–0.66, p < 0.001; > 50 years: aOR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.21–0.75, p = 0.004) compared to age ≤ 30 years, and those with higher monthly household income (> $501-$2000 USD: aOR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.31–0.87, p = 0.013; and > $2000 USD: aOR = 0.31, 95% CI 0.16–0.58, p < 0.001) compared to ≤ $500 USD. Participants reporting previous stressors (aOR = 3.05, 95% CI 1.95–4.75, p < 0.001) compared to no previous stressors, a previous mental health disorder (aOR = 2.97, 95% CI 1.65–5.32, p < 0.001) compared to none, and suboptimal ART adherence (< 95%) in the previous year (aOR = 2.41, 95% CI 1.23–4.75, p = 0.011) compared to adherence ≥ 95% were more likely to experience moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms. Moderate-to-high risk substance use was not found to be associated with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Factors associated with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms by PHQ-9

| Total patients | Number with moderate to severe depression | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | aOR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Total | 864 | 161 | ||||||

| Age at study assessment (years) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| ≤ 30 | 203 | 55 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 31–40 | 270 | 57 | 0.72 | (0.47, 1.10) | 0.131 | 0.81 | (0.51, 1.28) | 0.358 |

| 41–50 | 255 | 31 | 0.37 | (0.23, 0.61) | < 0.001 | 0.39 | (0.23, 0.66) | < 0.001 |

| > 50 | 136 | 18 | 0.41 | (0.23, 0.74) | 0.003 | 0.40 | (0.21, 0.75) | 0.004 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 758 | 149 | 1 | |||||

| Female | 106 | 12 | 0.52 | (0.28, 0.98) | 0.042 | |||

| Employment | < 0.001 | |||||||

| No | 180 | 49 | 2.41 | (1.59, 3.66) | < 0.001 | |||

| Full time | 499 | 67 | 1 | |||||

| Part time | 123 | 34 | 2.46 | (1.54, 3.95) | < 0.001 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 62 | 11 | ||||||

| Household income (USD) per month | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| ≤ $500 | 212 | 59 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| $501-$2000 | 258 | 40 | 0.48 | (0.30, 0.75) | 0.001 | 0.52 | (0.31, 0.87) | 0.013 |

| > $2000 | 257 | 28 | 0.32 | (0.19, 0.52) | < 0.001 | 0.31 | (0.16, 0.58) | < 0.001 |

| Not reported/unknown | 137 | 34 | ||||||

| Highest education level | ||||||||

| No education | 4 | 0 | N/A | |||||

| Primary to high school | 277 | 52 | 1.01 | (0.70, 1.45) | 0.975 | |||

| College to university | 562 | 105 | 1 | |||||

| Not reported/unknown | 21 | 4 | ||||||

| HIV mode of exposure | 0.031 | |||||||

| Heterosexual contact | 276 | 48 | 1 | |||||

| MSM | 460 | 78 | 0.97 | (0.65, 1.44) | 0.880 | |||

| Injecting drug use | 15 | 6 | 3.17 | (1.08, 9.31) | 0.036 | |||

| Other/Unknown | 113 | 29 | 1.64 | (0.97, 2.77) | 0.065 | |||

| Year of ART initiation | 0.066 | |||||||

| < 2010 | 236 | 31 | 1 | |||||

| 2010–2012 | 115 | 18 | 1.23 | (0.65, 2.30) | 0.524 | |||

| 2013–2015 | 189 | 41 | 1.83 | (1.10, 3.06) | 0.021 | |||

| 2016–2020 | 313 | 69 | 1.87 | (1.18, 2.97) | 0.008 | |||

| No ART/unknown | 11 | 2 | 1.47 | (0.30, 7.12) | 0.633 | |||

| Viral load at study assessment (copies/mL) | 0.016 | |||||||

| < 50 | 535 | 82 | 1 | |||||

| 50–399 | 37 | 7 | 1.29 | (0.55, 3.03) | 0.561 | |||

| 400–999 | 4 | 1 | 1.84 | (0.19, 17.92) | 0.599 | |||

| ≥ 1000 | 49 | 14 | 2.21 | (1.14, 4.29) | 0.019 | |||

| Not tested | 239 | 57 | ||||||

| CD4 at study assessment (cells/µL) | < 0.001 | |||||||

| ≤ 200 | 73 | 23 | 1 | |||||

| 201–350 | 94 | 21 | 0.63 | (0.31, 1.25) | 0.184 | |||

| 351–500 | 123 | 21 | 0.45 | (0.23, 0.88) | 0.021 | |||

| > 500 | 319 | 43 | 0.34 | (0.19, 0.61) | < 0.001 | |||

| Not tested | 255 | 53 | ||||||

| Current ART | 0.035 | |||||||

| NRTI + NNRTI | 455 | 88 | 1 | |||||

| NRTI + PI | 55 | 14 | 1.42 | (0.74, 2.73) | 0.286 | |||

| INSTI | 320 | 48 | 0.74 | (0.50, 1.08) | 0.119 | |||

| Other | 11 | 2 | 0.93 | (0.20, 4.37) | 0.923 | |||

| None/unknown | 23 | 9 | 2.68 | (1.12, 6.39) | 0.026 | |||

| ART adverse events in the previous year | ||||||||

| No | 603 | 88 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 93 | 15 | 1.13 | (0.62, 2.04) | 0.698 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 168 | 58 | ||||||

| ART adherence in the previous year | ||||||||

| ≥ 95 | 566 | 80 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| < 95 | 58 | 16 | 2.31 | (1.24, 4.31) | 0.008 | 2.41 | (1.23, 4.75) | 0.011 |

| Not reported/unknown | 240 | 65 | ||||||

| Prior AIDS diagnosis | ||||||||

| No | 556 | 85 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 202 | 37 | 1.24 | (0.81, 1.90) | 0.316 | |||

| Not reported | 106 | 39 | ||||||

| HIV disclosure status | 0.173 | |||||||

| Full | 41 | 9 | 1 | |||||

| Partial | 617 | 122 | 0.88 | (0.41, 1.88) | 0.735 | |||

| None, to no one | 162 | 22 | 0.56 | (0.24, 1.33) | 0.187 | |||

| No response/not reported/unknown | 44 | 8 | ||||||

| Hepatitis B co-infection | ||||||||

| Negative | 297 | 36 | 1 | |||||

| Positive | 34 | 3 | 0.70 | (0.20, 2.41) | 0.574 | |||

| Not tested | 533 | 122 | ||||||

| Hepatitis C co-infection | ||||||||

| Negative | 410 | 46 | 1 | |||||

| Positive | 30 | 3 | 0.88 | (0.26, 3.01) | 0.838 | |||

| Not tested | 424 | 112 | ||||||

| History of STIs in the past 5 years | ||||||||

| No | 413 | 58 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 263 | 43 | 1.20 | (0.78, 1.84) | 0.413 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 188 | 60 | ||||||

| Current chronic comorbid condition | ||||||||

| No | 352 | 58 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 150 | 32 | 1.37 | (0.85, 2.22) | 0.195 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 362 | 71 | ||||||

| Previous mental health diagnosis | ||||||||

| No | 639 | 83 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 67 | 25 | 3.99 | (2.31, 6.88) | < 0.001 | 2.97 | (1.65, 5.32) | < 0.001 |

| Not reported/unknown | 158 | 53 | ||||||

| Family history of mental health diagnoses | ||||||||

| No | 739 | 125 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 34 | 9 | 1.77 | (0.81, 3.88) | 0.155 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 91 | 27 | ||||||

| Previous stressors | ||||||||

| No | 369 | 32 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 437 | 116 | 3.81 | (2.50, 5.79) | < 0.001 | 3.05 | (1.95, 4.75) | < 0.001 |

| Not reported/unknown | 58 | 13 | ||||||

| Moderate to high risk substance use | ||||||||

| No | 439 | 68 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 425 | 93 | 1.53 | (1.08, 2.16) | 0.016 | |||

| World Bank country income grouping | ||||||||

| High | 334 | 52 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Upper-middle and lower-middle | 530 | 109 | 1.40 | (0.98, 2.02) | 0.067 | 0.82 | (0.49, 1.36) | 0.435 |

Not reported values were included in the analysis as a separate category but were excluded from test for heterogeneity

Global p-value for age, viral load, CD4, household income were test for trend

OR odds ratio, aOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval, ART antiretroviral therapy, STIs sexually transmitted infections, MSM men who have sex with men, NRTI nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, NNRTI non-NRTI, PI protease inhibitors, INSTI integrase inhibitors

Prevalence of Substance Use and Substance Use Risk

On screening with ASSIST, 681 (80%) participants reported ever using at least one substance, and 553 (64%) reported using at least one substance in the past three months. Of those who ever used at least one substance, 407 (60%) used tobacco, 597 (88%) alcohol, 130 (19%) cannabis, 36 (5%) cocaine, 151 (22%) amphetamines, 33 (5%) inhalants, 101 (15%) sedatives, 43 (6%) hallucinogens, and 21 (3%) opioids (Table 3). Of those who used at least one substance in the past three months, 282 (51%) used tobacco, 443 (80%) alcohol, 40 (7%) cannabis, 7 (1%) cocaine, 69 (12%) amphetamines, 14 (3%) inhalants, 62 (11%) sedatives, 7 (1%) hallucinogens, and 2 (0%) opioids.

Table 3.

ASSIST screening of recent and lifetime substance use, and risk-level

| Substance | Total patients used substance in last 3 months (%) | Total patients ever used substance (%) | Total patients with lower risk (%) | Total patients with moderate risk (%) | Total patients with high risk (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | 282 (51) | 407 (60) | 123 (30) | 252 (62) | 32 (8) |

| Alcohol | 443 (80) | 597 (88) | 376 (63) | 184 (31) | 37 (6) |

| Cannabis | 40 (7) | 130 (19) | 101 (78) | 29 (22) | 0 (0) |

| Cocaine | 7 (1) | 36 (5) | 31 (86) | 5 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Amphetamines | 69 (12) | 151 (22) | 75 (50) | 66 (44) | 10 (7) |

| Inhalants | 14 (3) | 33 (5) | 19 (58) | 13 (39) | 1 (3) |

| Sedatives | 62 (11) | 101 (15) | 47 (47) | 50 (50) | 4 (4) |

| Hallucinogens | 7 (1) | 43 (6) | 39 (91) | 4 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Opioids | 2 (0) | 21 (3) | 17 (81) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 4 (1) | 14 (2) | 9 (64) | 5 (36) | 0 (0) |

| Total patients | 553 | 681 | 447 | 398 | 69 |

A participant may take multiple substances and the total patients at the bottom of each column is the count of individual patients. Percentages are column percentages for recent and lifetime substance use columns. Percentages are row percentages for risk-level columns

Of the 681 study participants who ever used at least one substance, 425 (62%) were classified as having moderate-to-high risk ASSIST scores to any drug. This included 284/407 (70%) of those that ever used tobacco, 221/597 (37%) alcohol, 29/130 (22%) cannabis, 5/36 (14%) cocaine, 76/151 (51%) amphetamine, 14/33 (42%) inhalants, 54/101 (54%) sedatives, 4/43 (9%) hallucinogens, and 4/21 (19%) of those that ever used opioids.

Factors Associated with Substance Use Risk

Overall, 425 (49%) were classified as having moderate-to-high risk substance use to any drug. Multivariate analyses indicated that those age > 50 years (aOR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.37–0.96, p = 0.033) compared to age ≤ 30 years, and females (aOR = 0.38, 95% CI 0.23–0.61, p < 0.001) compared to males, were less likely to report moderate-to-high risk substance use (Table 4). Those who had partially (aOR = 0.30, 95% CI 0.14–0.63, p = 0.002) or not disclosed their HIV status to others (aOR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.15–0.74, p = 0.007) compared to those who had fully disclosed, and participants from upper-middle and lower-middle income countries (aOR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.43–0.82, p = 0.001) compared to those from high-income countries, were less likely to report moderate-to-high risk substance use. Participants in part-time employment (aOR = 2.07, 95% CI 1.34–3.19, p = 0.001) compared to full time, and those reporting previous stressors (aOR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.21–2.20, p = 0.001) compared to none, and suboptimal ART adherence (< 95%) in the previous year (aOR = 2.90, 95% CI 1.55–5.40, p = 0.001) compared to adherence ≥ 95% were more likely to report moderate-to-high risk substance use. Moderate-to-severe depression was not found to be associated with moderate-to-high risk substance use.

Table 4.

Factors associated with moderate to high risk substance use

| Total patients | Number with moderate to high risk substance use | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | aOR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Total | 864 | 425 | ||||||

| Age at study assessment (years) | 0.002 | 0.008 | ||||||

| ≤ 30 | 203 | 107 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 31–40 | 270 | 152 | 1.16 | (0.80, 1.67) | 0.438 | 1.24 | (0.84, 1.82) | 0.279 |

| 41–50 | 255 | 112 | 0.70 | (0.49, 1.02) | 0.062 | 0.78 | (0.52, 1.16) | 0.213 |

| > 50 | 136 | 54 | 0.59 | (0.38, 0.92) | 0.019 | 0.60 | (0.37, 0.96) | 0.033 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 758 | 398 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 106 | 27 | 0.31 | (0.20, 0.49) | < 0.001 | 0.38 | (0.23, 0.61) | < 0.001 |

| HIV mode of exposure | 0.096 | |||||||

| Heterosexual contact | 276 | 119 | 1 | |||||

| MSM | 460 | 238 | 1.41 | (1.05, 1.91) | 0.024 | |||

| Injecting drug use | 15 | 9 | 1.98 | (0.69, 5.71) | 0.207 | |||

| Other/Unknown | 113 | 59 | 1.44 | (0.93, 2.24) | 0.103 | |||

| Viral load at study assessment (copies/mL) | 0.982 | |||||||

| < 50 | 535 | 256 | 1 | |||||

| 50–399 | 37 | 16 | 0.83 | (0.42, 1.63) | 0.588 | |||

| 400–999 | 4 | 0 | N/A | |||||

| ≥ 1000 | 49 | 25 | 1.14 | (0.63, 2.04) | 0.671 | |||

| Not tested | 239 | 128 | ||||||

| CD4 at study assessment (cells/µL) | 0.179 | |||||||

| ≤ 200 | 73 | 29 | 1 | |||||

| 201–350 | 94 | 49 | 1.65 | (0.89, 3.07) | 0.112 | |||

| 351–500 | 123 | 54 | 1.19 | (0.66, 2.14) | 0.567 | |||

| > 500 | 319 | 163 | 1.59 | (0.94, 2.66) | 0.081 | |||

| Not tested | 255 | 130 | ||||||

| Current ART | 0.270 | |||||||

| NRTI + NNRTI | 455 | 214 | 1 | |||||

| NRTI + PI | 55 | 28 | 1.17 | (0.67, 2.04) | 0.587 | |||

| INSTI | 320 | 163 | 1.17 | (0.88, 1.56) | 0.284 | |||

| Other | 11 | 9 | 5.07 | (1.08, 23.71) | 0.039 | |||

| None/unknown | 23 | 11 | 1.03 | (0.45, 2.39) | 0.941 | |||

| Hepatitis B co-infection | ||||||||

| Negative | 297 | 132 | 1 | |||||

| Positive | 34 | 8 | 0.38 | (0.17, 0.88) | 0.023 | |||

| Not tested | 533 | 285 | ||||||

| Hepatitis C co-infection | ||||||||

| Negative | 410 | 169 | 1 | |||||

| Positive | 30 | 13 | 1.09 | (0.52, 2.30) | 0.821 | |||

| Not tested | 424 | 243 | ||||||

| Prior AIDS diagnosis | ||||||||

| No | 556 | 268 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 202 | 100 | 1.05 | (0.76, 1.45) | 0.751 | |||

| Not reported | 106 | 57 | ||||||

| Household income (USD) per month | 0.012 | |||||||

| ≤ $500 | 212 | 95 | 1 | |||||

| $501–$2000 | 258 | 112 | 0.94 | (0.66, 1.36) | 0.761 | |||

| > $2000 | 257 | 144 | 1.57 | (1.09, 2.26) | 0.016 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 137 | 74 | ||||||

| Employment | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| No | 180 | 78 | 0.87 | (0.61, 1.22) | 0.411 | 0.76 | (0.52, 1.12) | 0.168 |

| Full time | 499 | 234 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Part time | 123 | 79 | 2.03 | (1.35, 3.06) | 0.001 | 2.07 | (1.34, 3.19) | 0.001 |

| Not reported/unknown | 62 | 34 | ||||||

| Highest education level | 0.579 | |||||||

| No education | 4 | 1 | 0.34 | (0.03, 3.25) | 0.346 | |||

| Primary to high school | 277 | 133 | 0.93 | (0.70, 1.24) | 0.622 | |||

| College to university | 562 | 280 | 1 | |||||

| Not reported/unknown | 21 | 11 | ||||||

| HIV disclosure status | 0.025 | 0.007 | ||||||

| Full | 41 | 29 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Partial | 617 | 302 | 0.40 | (0.20, 0.79) | 0.009 | 0.30 | (0.14, 0.63) | 0.002 |

| None, to no one | 162 | 76 | 0.37 | (0.17, 0.77) | 0.008 | 0.33 | (0.15, 0.74) | 0.007 |

| No response/not reported/unknown | 44 | 18 | ||||||

| Previous stressors | ||||||||

| No | 369 | 156 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 437 | 238 | 1.63 | (1.23, 2.16) | 0.001 | 1.63 | (1.21, 2.20) | 0.001 |

| Not reported/unknown | 58 | 31 | ||||||

| Current chronic comorbid condition | ||||||||

| No | 352 | 191 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 150 | 76 | 0.87 | (0.59, 1.27) | 0.460 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 362 | 158 | ||||||

| Previous mental health diagnosis | ||||||||

| No | 639 | 297 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 67 | 39 | 1.60 | (0.96, 2.67) | 0.069 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 158 | 89 | ||||||

| Family history of mental health diagnoses | ||||||||

| No | 739 | 349 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 34 | 23 | 2.34 | (1.12, 4.86) | 0.023 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 91 | 53 | ||||||

| History of STIs in the past 5 years | ||||||||

| No | 413 | 167 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 263 | 153 | 2.05 | (1.50, 2.80) | < 0.001 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 188 | 105 | ||||||

| Year of ART initiation | 0.045 | |||||||

| < 2010 | 236 | 97 | 1 | |||||

| 2010–2012 | 115 | 61 | 1.62 | (1.03, 2.54) | 0.035 | |||

| 2013–2015 | 189 | 93 | 1.39 | (0.94, 2.04) | 0.095 | |||

| 2016–2020 | 313 | 169 | 1.68 | (1.20, 2.37) | 0.003 | |||

| No ART/unknown | 11 | 5 | 1.19 | (0.35, 4.02) | 0.775 | |||

| ART adverse events in the previous year | ||||||||

| No | 603 | 290 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 93 | 41 | 0.85 | (0.55, 1.32) | 0.472 | |||

| Not reported/unknown | 168 | 94 | ||||||

| ART adherence in the previous year | ||||||||

| ≥ 95 | 566 | 259 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| < 95 | 58 | 41 | 2.86 | (1.59, 5.15) | < 0.001 | 2.90 | (1.55, 5.40) | 0.001 |

| Not reported/unknown | 240 | 125 | ||||||

| Moderate to severe depression | ||||||||

| No | 703 | 332 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 161 | 93 | 1.53 | (1.08, 2.16) | 0.016 | |||

| World Bank country income grouping | ||||||||

| High | 334 | 187 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Upper-middle and lower-middle | 530 | 238 | 0.64 | (0.49, 0.84) | 0.002 | 0.60 | (0.43, 0.82) | 0.001 |

Not reported values were included in the analysis as a separate category but were excluded from test for heterogeneity

Global p-value forage, viral load, CD4, household income were test for trend

OR odds ratio, aOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval, ART antiretroviral therapy, STIs sexually transmitted infections, MSM men who have sex with men, NRTI nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, NNRTI non-NRTI, PI protease inhibitors, INSTI integrase inhibitors

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of 864 adult PLHIV in care at five HIV clinical sites in five countries in the Asia–Pacific region, 19% had moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms, 19% had suicidal thoughts, 80% ever used at least one substance, and 64% used at least one substance in the past three months. Alcohol, tobacco, amphetamine, sedative, and cannabis use was common, as was moderate-to-high risk substance use. Moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms and moderate-to-high risk substance use were both associated with younger age, previous stressors, and previous suboptimal ART adherence. Neither was associated with mean CD4 cell count or VL < 1000 copies/mL. We found no association between moderate-to-high risk substance use and moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms.

Rates and risk factors for depressive symptoms in our cohort are consistent with those documented in similar adult PLHIV cohorts in the region, for example a study of predominantly male adult PLHIV in Southern India, screened using PHQ-9, found that 23% had moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms [26] and a meta-analysis of PLHIV in sub-Saharan Africa found a 14% prevalence of depressive symptoms among PLHIV on ART based on a PHQ-9 cut-off score of ≥ 10 [27]. The same analysis found depressive symptoms were associated with lower personal income, and an analysis of adult PLHIV in East Africa found both stressful life events and low personal income were associated with depression [28]. Rates of suicidal thoughts in our cohort appear higher than those documented elsewhere. A recent study of adult PLHIV in Indonesia identified lifetime suicidal ideation in 23% [29], and a survey of adult PLHIV in Nigeria found a 12-month prevalence rate for suicidal ideation of 2.9% [30]. These differences are likely explained by differences in screening instruments used, and differences in key sociodemographic characteristics often linked to mental health status, such as sex, age, marital status, and income and education levels.

The high rates of alcohol and tobacco use found in our cohort are consistent with those observed in other adult PLHIV cohorts in the region. Studies among HIV-positive adults in Nepal and India found a prevalence of alcohol use disorder of 25.7 and 12.8% [31, 32]. Recent tobacco use among adult men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) living with HIV in Taiwan was just under 50% [33]. Amphetamine use in our adult PLHIV cohort are consistent with those reported in populations at risk of HIV infection in the region, with rates of 7% reported among Cambodian female sex workers [34] and 30% among MSM in Vietnam [35]. Although the substantial proportions of sedative users in our cohort have not been widely documented elsewhere in the region, a study in Taiwan did find that PLHIV had an increased risk of sedative use compared to those without HIV, after adjusting for demographic data and psychiatric comorbidities [36]. Factors associated with moderate-to-high risk substance use are also consistent with those identified in cohorts elsewhere. Meta-analyses have found higher prevalence of both alcohol use disorders and current smoking among male PLHIV than female PLHIV, and a higher prevalence of alcohol use disorders among PLHIV in developed countries than those in developing countries [37, 38].

Our finding that those with suboptimal adherence in the previous year were more likely to experience moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms and report moderate-to-high risk substance use adds to the substantial body of evidence from this region linking mental health issues, substance use and poorer adherence across different adult PLHIV populations [20, 32, 39–43]. Our finding that mean CD4 cell count and viral load < 1000 copies/mL were not risk factors for moderate-to-high risk substance use or moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms, adds to the insubstantial and conflicting regional evidence of associations between mental health or substance use and HIV clinical or treatment outcomes. In a systematic review published in 2018, none of the three Asia–Pacific studies included identified mental health disorders or substance use to be a predictor of poor retention in HIV care for adults living with HIV [14]. However, an analysis of adult PLHIV in South Korea did find patients with depression were more likely to frequently miss clinical appointments and have a higher cumulative time lost to follow-up per month compared to patients without depression [44]. Among HIV-positive heterosexual men and MSM in Thailand, non-injection substance use was associated with a lower likelihood of having an undetectable viral load [45], but a study of predominantly male adult PLHIV in care at community and hospital-based ART clinics in Vietnam found no association between mental health symptoms and virologic suppression [46].

Despite a high burden of depression and substance use, and the potential for negative impacts on HIV clinical outcomes, there remain substantial gaps in access to mental health and substance use related care for adult PLHIV in the region, and fragmented integration of related services within HIV clinical settings. In a global analysis, only 43% of 28 HIV clinical Asia–Pacific sites screened for depression and 39% for substance use disorders, rates of screening that were among the lowest of any region [47]. We feel the relatively low screening rates for depression and substance use in HIV clinical settings in the region are likely reflective of a general lack of resources dedicated to addressing mental health and substance use issues across all settings and populations in the region, and related to this, limited capacity of health care workers and health systems to support the delivery of such services [22]. The same global analysis reported on-site management of substance use disorders in 57%, and another global analysis noted substantial gaps persist in the integration of substance use services into HIV care settings, particularly in resource-constrained settings [48]. A study in Malaysia published in 2020, found that over 80% of adult PLHIV with prevalent psychiatric symptoms had not previously been recognized clinically, and that only 32% of participants with severe mental health symptoms received a psychiatric referral [49]. This limited integration is in spite of growing regional evidence of the effectiveness of non-pharmacological mental health and substance use interventions among adult PLHIV populations, including telephone-based behavioral therapy [50], group coping interventions [51], group rational-emotive-behavior-based therapy [52], brief cognitive behavioral therapy interventions [53], and home-based social support [54].

Further integration of mental health and substance use services within HIV clinical settings in the region is exacerbated by a lack of local research on optimal integration models and strategies. In recent systematic reviews of interventions and approaches to integrating HIV, mental health or substance use services, none or very few of the eligible articles were from the Asia–Pacific region [55, 56]. The limited research on approaches to integrating HIV, mental health and substance use services in the region are likely related to a lack of implementation research capacities in the region, and the relatively recent emergence of implementation research as a priority research discipline in the region. Indeed, the importance of implementation research to inform the integration, adaptation or scale-up of mental health or substance use services within HIV care in Asian or resource-limited settings is increasingly being highlighted [48, 57, 58].

It is worth noting that our study had a number of limitations. As a cross-sectional study, it can say nothing of trends in mental health or substance use disorders, or incidence levels. Study methodology did not support assessment of causal relationships between depression, substance use and HIV clinical and treatment outcomes. Because study participants were only recruited from adult PLHIV in routine care, those with more severe mental health or substance use issues may have dropped out of care, raising the potential for sampling bias. Formal validation of translated mental health and substance use screening tools was not conducted among the study population. Despite these limitations, we feel the study provides an informative picture of the mental health and substance use burden, risks and impacts among adults living with HIV in the region in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic period.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of mild to severe depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and substance use, and their association with suboptimal ART adherence, in our adult PLHIV cohort highlight the need to improve access to and integration of mental health and substance use screening and management in HIV clinical settings in the Asia–Pacific region. Enhanced linkages to specialist mental health care for further assessment or interventions, should also be considered in the context of HIV clinical settings. It is important that service integration is localised to address local mental health and substance use issues, particularly depression, suicidality, tobacco, alcohol, amphetamine and sedative use. Further implementation research would inform optimal approaches to integrating mental health and substance use services within HIV care in the region.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the study participants and all site staff for their commitment to the study. The S2D2 Study Group: MP Lee, I Chan, YT Chan, SM Au, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR; JY Choi, Na S, JH Kim, JM Kim, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea; I Azwa, R Rajasuriar, ML Chong, JY Ong, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; R Ditangco, MI Melgar, ES Gomez, Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Muntinlupa City, Philippines; A Avihingsanon, C Padungpol, J Jamthong, S Thammasala, S Phonphithak, P Chaiyahong, HIV-NAT/Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand; AH Sohn, JL Ross, B Petersen, C Chansilpa, TREAT Asia, amfAR, Bangkok, Thailand; MG Law, A Jiamsakul, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, Australia.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by AJ, SG, IC, MIEM, JHK, and MLC. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JLR and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding support was provided through a grant to amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research from the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the Fogarty International Center (IeDEA; U01AI069907). The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The content of this research is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the institutions above.

Data Availability

Study data available on request.

Code Availability

Codes available on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the following institutional research ethics committees: Research Ethics Committee (Kowloon Central / Kowloon East), Hospital Authority IRB, Hong Kong SAR; Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) Institutional Review Board, Muntinlupa City, the Philippines; Severance Hospital Yonsei University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board, Seoul, South Korea; Institutional Review Board Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand; Medical Research Ethics Committee, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), The University of New South Wales, UNSW Sydney, NSW, Australia; and Advarra, Inc. Institutional Review Board, Maryland, U.S.A.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable. Identifying information, data or photographs of individuals are not included in this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics 2021.

- 2.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, Robbins RN, Pala AN, Mellins CA. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS (London, England) 2019;33(9):1411–1420. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):725–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt R. The mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: a systematic review. Afr J AIDS Res. 2009;8(2):123–133. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.2.1.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parcesepe AM, Bernard C, Agler R, Ross J, Yotebieng M, Bass J, et al. Mental health and HIV: research priorities related to the implementation and scale up of 'treat all' in sub-Saharan Africa. J Virus Erad. 2018;4(Suppl 2):16–25. doi: 10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30341-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pence BW, Mills JC, Bengtson AM, Gaynes BN, Breger TL, Cook RL, et al. Association of increased chronicity of depression with HIV appointment attendance, treatment failure, and mortality among HIV-infected adults in the United States. JAMA Psychiat. 2018;75(4):379–385. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas AD, Ruffieux Y, van den Heuvel LL, Lund C, Boulle A, Euvrard J, et al. Excess mortality associated with mental illness in people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: a cohort study using linked electronic health records. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(10):e1326–e1334. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams JW, Bryant KJ, Edelman EJ, Fiellin DA, Gaither JR, Gordon AJ, et al. Association of cannabis, stimulant, and alcohol use with mortality prognosis among HIV-infected men. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1341–1351. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1905-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montgomery L, Bagot K, Brown JL, Haeny AM. The association between marijuana use and HIV continuum of care outcomes: a systematic review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019;16(1):17–28. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00422-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Velloza J, Kemp CG, Aunon FM, Ramaiya MK, Creegan E, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral therapy non-adherence among adults living with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(6):1727–1742. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02716-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayston R, Kinyanda E, Chishinga N, Prince M, Patel V. Mental disorder and the outcome of HIV/AIDS in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. AIDS (London, England) 2012;26(Suppl 2):S117–S135. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835bde0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB. Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle- and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(3):291–307. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0220-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bulsara SM, Wainberg ML, Newton-John TRO. Predictors of adult retention in HIV care: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(3):752–764. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1644-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shubber Z, Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Vreeman R, Freitas M, Bock P, et al. Patient-reported barriers to adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(11):e1002183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatia MS, Munjal S. Prevalence of depression in people living with HIV/AIDS undergoing ART and factors associated with it. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:WC01. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7725.4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu L, Luo D, Liu Y, Silenzio VM, Xiao S. The mental health of people living with HIV in China, 1998–2014: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0153489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thai TT, Jones MK, Harris LM, Heard RC, Hills NK, Lindan CP. Symptoms of depression in people living with HIV in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: prevalence and associated factors. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(Suppl 1):76–84. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1946-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright E, Brew B, Arayawichanont A, Robertson K, Samintharapanya K, Kongsaengdao S, et al. Neurologic disorders are prevalent in HIV-positive outpatients in the Asia-Pacific region. Neurology. 2008;71(1):50–56. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316390.17248.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prasithsirikul W, Chongthawonsatid S, Ohata PJ, Keadpudsa S, Klinbuayaem V, Rerksirikul P, et al. Depression and anxiety were low amongst virally suppressed, long-term treated HIV-infected individuals enrolled in a public sector antiretroviral program in Thailand. AIDS Care. 2017;29(3):299–305. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1201194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang T, Fu H, Kaminga AC, Li Z, Guo G, Chen L, et al. Prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1741-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2020. 2021.

- 23.PHQ9. https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline/patient-health-questionnaire.pdf

- 24.World Health Organization. ASSIST. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924159938-2

- 25.World Health Organization. Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO disability assessment schedule (WHODAS 2.0). 2010.

- 26.Chan BT, Pradeep A, Prasad L, Murugesan V, Chandrasekaran E, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevalence and correlates of psychosocial conditions among people living with HIV in southern India. AIDS Care. 2017;29(6):746–750. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1231887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard C, Dabis F, de Rekeneire N. Prevalence and factors associated with depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0181960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayano G, Solomon M, Abraha M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiology of depression in people living with HIV in east Africa. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):254. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1835-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ophinni Y, Adrian Siste K, Wiwie M, Anindyajati G, Hanafi E, et al. Suicidal ideation, psychopathology and associated factors among HIV-infected adults in Indonesia. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02666-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egbe CO, Dakum PS, Ekong E, Kohrt BA, Minto JG, Ticao CJ. Depression, suicidality, and alcohol use disorder among people living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):542. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4467-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayston R, Patel V, Abas M, Korgaonkar P, Paranjape R, Rodrigues S, et al. Determinants of common mental disorder, alcohol use disorder and cognitive morbidity among people coming for HIV testing in Goa, India. TM & IH. 2015;20(3):397–406. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pokhrel KN, GauleePokhrel K, Neupane SR, Sharma VD. Harmful alcohol drinking among HIV-positive people in Nepal: an overlooked threat to anti-retroviral therapy adherence and health-related quality of life. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1441783. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1441783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen WT, Shiu C, Yang JP, Chuang P, Berg K, Chen LC, et al. Tobacco, alcohol, drug use, and intimate partner violence among MSM living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2019;30(6):610–618. doi: 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans JL, Couture MC, Carrico A, Stein ES, Muth S, Phou M, et al. Joint effects of alcohol and stimulant use disorders on self-reported sexually transmitted infections in a prospective study of Cambodian female entertainment and sex workers. Int J STD AIDS. 2021;32(4):304–313. doi: 10.1177/0956462420964647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vu NTT, Holt M, Phan HTT, La LT, Tran GM, Doan TT, et al. Amphetamine-type-stimulants (ATS) use and homosexuality-related enacted stigma are associated with depression among men who have sex with men (MSM) in two major cities in Vietnam in 2014. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(11):1411–1419. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1284233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei HT, Chen MH, Wong WW, Chou YH, Liou YJ, Su TP, et al. Benzodiazepines and Z-drug use among HIV-infected patients in Taiwan: a 13-year nationwide cohort study. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:465726. doi: 10.1155/2015/465726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duko B, Ayalew M, Ayano G. The prevalence of alcohol use disorders among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2019;14(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s13011-019-0240-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinberger AH, Smith PH, Funk AP, Rabin S, Shuter J. Sex differences in tobacco use among persons living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(4):439–53. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JY, Yang Y, Kim HK, Kim JY. The impact of alcohol use on antiretroviral therapy adherence in Koreans living with HIV. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2018;12(4):258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tao J, Qian HZ, Kipp AM, Ruan Y, Shepherd BE, Amico KR, et al. Effects of depression and anxiety on antiretroviral therapy adherence among newly diagnosed HIV-infected Chinese MSM. AIDS (London, England) 2017;31(3):401–406. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Do HM, Dunne MP, Kato M, Pham CV, Nguyen KV. Factors associated with suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Viet Nam: a cross-sectional study using audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bijker R, Jiamsakul A, Kityo C, Kiertiburanakul S, Siwale M, Phanuphak P, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia: a comparative analysis of two regional cohorts. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21218. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chakraborty A, Hershow RC, Qato DM, Stayner L, Dworkin MS. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV patients in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(7):2130–2148. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02779-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song JY, Lee JS, Seo YB, Kim IS, Noh JY, Baek JH, et al. Depression among HIV-infected patients in Korea: assessment of clinical significance and risk factors. Infect Chemother. 2013;45(2):211–216. doi: 10.3947/ic.2013.45.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuyuki K, Shoptaw SJ, Ransome Y, Chau G, Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Friedman RK, et al. The longitudinal effects of non-injection substance use on sustained HIV viral load undetectability among MSM and heterosexual men in Brazil and Thailand: the role of ART adherence and depressive symptoms (HPTN 063) AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):649–660. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02415-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen MX, McNaughton Reyes HL, Pence BW, Muessig K, Hutton HE, Latkin CA, et al. The longitudinal association between depression, anxiety symptoms and HIV outcomes, and the modifying effect of alcohol dependence among ART clients with hazardous alcohol use in Vietnam. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(Suppl 2):e25746. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parcesepe AM, Mugglin C, Nalugoda F, Bernard C, Yunihastuti E, Althoff K, et al. Screening and management of mental health and substance use disorders in HIV treatment settings in low- and middle-income countries within the global IeDEA consortium. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(3):e25101. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parcesepe AM, Lancaster K, Edelman EJ, DeBoni R, Ross J, Atwoli L, et al. Substance use service availability in HIV treatment programs: data from the global IeDEA consortium, 2014–2015 and 2017. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meng Li C, Jie Ying F, Raj D, Pui Li W, Kukreja A, Omar SF, et al. A retrospective analysis of the care cascades for non-communicable disease and mental health among people living with HIV at a tertiary-care centre in Malaysia: opportunities to identify gaps and optimize care. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(11):e25638. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo Y, Hong YA, Cai W, Li L, Hao Y, Qiao J, et al. Effect of a wechat-based intervention (Run4Love) on depressive symptoms among people living with HIV in China: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(2):e16715. doi: 10.2196/16715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye Z, Chen L, Lin D. The relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and posttraumatic growth among HIV-infected men who have sex with men in Beijing, China: the mediating roles of coping strategies. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1787. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Surilena Ismail RI, Irwanto Djoerban Z, Utomo B, Sabarinah, et al. The effect of rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) on antiretroviral therapeutic adherence and mental health in women infected with HIV/AIDS. Acta Med Indones. 2014;46(4):283–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang JP, Simoni JM, Dorsey S, Lin Z, Sun M, Bao M, et al. Reducing distress and promoting resilience: a preliminary trial of a CBT skills intervention among recently HIV-diagnosed MSM in China. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup5):S39–S48. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1497768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pokhrel KN, Sharma VD, Pokhrel KG, Neupane SR, Mlunde LB, Poudel KC, et al. Investigating the impact of a community home-based care on mental health and anti-retroviral therapy adherence in people living with HIV in Nepal: a community intervention study. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):263. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3170-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chuah FLH, Haldane VE, Cervero-Liceras F, Ong SE, Sigfrid LA, Murphy G, et al. Interventions and approaches to integrating HIV and mental health services: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(4):iv27–iv47. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haldane V, Cervero-Liceras F, Chuah FL, Ong SE, Murphy G, Sigfrid L, et al. Integrating HIV and substance use services: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21585. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sohn AH, Ross J, Wainberg ML. Barriers to mental healthcare and treatment for people living with HIV in the Asia-Pacific. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(10):e25189. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Senn TE, Greenwood GL, Rao VR. Global mental health and HIV care: gaps and research priorities. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(Suppl 2):e25714. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Study data available on request.

Codes available on request.