Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Many measures have been taken so far to minimize the outbreak of COVID-19, but it is still unclear to what extent people have understood the risk. Public participation plays a vital role in better and effective control of the coronavirus, and the importance of risk perception is effective in their preventive behavior. The aim of this study was to investigate the pandemic risk perception of coronavirus disease after began of pandemic in Iranian society.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Iran in spring 2020. The data collection tool was a researcher-made questionnaire. The questions were extracted through interviews with experts and summarizing the opinions of public interviews, etc., The questionnaire was made available to the public through social media. The information was collected within 3 months. Quantitative data were reported as mean ± standard deviation and the qualitative data were reported as number and percent. Multiple linear regression and cross were also used to examine the demographic factors associated with risk perception. Data Analysis was performed using the SPSS version 21 statistical software.

RESULTS:

In this study, 402 individuals from 28 provinces (Azarbaijan Gharbi, Azarbaijan Sharghi, Alborz, Ardabil, Bushehr, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Esfahan, Fars, Ghazvin, Gilan, Golestan, Hamedan, Hormozgan, Ilam, Kerman, Kermanshah, Khorasan Razavi, Khorasan Shomali, Khuzestan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyerahmad, Kurdistan, Lorestan, Mazandaran, Semnan, Sistan and Baluchestan, Tehran, Yazd, and Zanjan) of Iran participated. The risk perception score obtained from the sum of the scores of the questions was classified into quartiles. Accordingly, the risk perception score of (22.9) 92 people was very low, (26.6) 107 people low, (26.9) 108 people moderate, and (23.6) 95 people high. The results of multiple linear regression showed that the variables of gender (P = 0.008) and occupation (P = 0.013) had a significant relationship with risk perception. There was no significant relationship between risk perception and variables of age, marital status, and level of education (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION:

The study showed that the risk perception of the people is more in categories of moderate to high. Assessing the risk perception of a pandemic can be helpful for preventive measurements and planning, and also, according to the results of the research, can be done appropriate educational interventions. Given that 47.5% of respondents were employees, of course, it should be noted that in sending a questionnaire virtually, there is usually a lot of loss and this is a limitation of the research. The results of this study can be useful in making prevention decisions and maintaining safety and health in the workplace.

Keywords: Behavior, COVID-19, health, knowledge, pandemics, perception, risk

Introduction

The coronavirus gets transmitted through contact with respiratory droplets caused by coughing or sneezing of an infected person, or touching objects and surfaces that contain sneezing droplets of an infected person.[1,2,3] Given the unknowns of coronavirus and the fact that there has been no specific treatment for this virus so far, the only way to deal with it and the most cost-effective way is prevention. China's experience has shown that the most important way to control the transmission of the virus is social distancing and staying at home.[4]

Studies have shown that it is very important for the general population to be aware of the dangers and how to behave in times of pandemics. Also, assessment of public perceptions of risk, protective behaviors, as well as correct knowledge and information are necessary for health education.[5] At first, we should find the level of risk perception of a population about a pandemic; after that, we can modify a plan for controlling. Maybe, it should be necessary to increase awareness by training about protective behaviors such as mask wearing, handwashing, and social distancing. Due to this, it is still unclear to what extent people are aware of the risks associated with COVID-19, how to change their behavior, and how well they understand the risks involved.[6] The results of studies have shown that in an emergency situation, the reactions and how people behave are determined according to their perception of risks and the extent of injuries.[7] Risk perception is the subjective assessment process of the probability of a specific event and how to deal with its consequences. It is very important in health and safety, and many events occur because people do not have a proper understanding of the risks.[8] According to the theory of protection motivation, new hazards are considered unfamiliar and uncontrollable, which leads to greater protection motivation and thus higher understanding.[9] Furthermore, the occurrence of the negative consequences of disasters is associated with low-risk perception.[10] Studies have shown that timely psychological and behavioral assessment of the community is useful for awareness of next interventions and risk-related strategies with the progression of the pandemic.[11] The results of the risk perception study by Wise et al. showed that a group of people, who were mostly unaware, did not perform protective behaviors.[12] In the study of factors affecting Iranians’ risk perception by Samadipour and Ghardashi, the results showed that religious, cultural, political, cognitive, social, and emotional factors were effective in Iranians’ risk perception of COVID-19.[7] In some countries, including China, the United States, and Germany, research has been conducted on the risk perception of coronavirus. These studies investigate how protective behaviors are predicted through individuals’ risk perceptions.[5,8,12] Public participation plays a vital role in the better and more effective control of coronavirus disease. Risk perception is important in preventive behavior. Hence, the aim of this study was to assess the pandemic risk perception of coronavirus (COVID-19) after four peak periods of the disease in Iran in spring and the results can show us a picture of Iranian risk perception about the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted for 3 months in spring 2020 (the beginning of the Corona pandemic) to investigate the risk perception of coronavirus in Iran. The sampling method was availability sampling.

Study participants and sampling

The study population was from different cities in Iran. Data were collected using a researcher-made questionnaire. The general questionnaire was included demographic variables and a risk perception questionnaire. Inclusion criteria were willingness to complete the questionnaire, access smartphones and cyberspace, and live in Iran and the exclusion criteria were unwillingness to continue cooperation and lack of answers to all questionnaire questions.

The results of the reliability study after removing a question showed that the internal reliability of the attitude awareness subscale increased to 0.70 and the perspective attitude subscale increased to 0.70 and the performance behavior subscale was 0.85.

After that, a researcher-made questionnaire was developed and designed on the network virtually, then its link was available to the social media same as (WhatsApp, Telegram).

First, the aim of this study and the subject of the research were explained to the participants. Participants were reassured that their information would remain confidential.

Data collection tool and technique

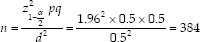

Incomplete questionnaires were not recorded in this analysis. In this study, an easy and available sampling method was used, and the sample size was estimated to be 384 individuals based on the Cochran formula. d = 0.05, P = Q = 0.5, α = 0.05.

The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were acceptable, considering Cronbach's alpha (alpha number: 0.72). Quantitative data were reported as mean ± standard deviation and the qualitative data were reported as numbers. Multiple linear regression was also used to examine the demographic factors associated with risk perception. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software.

Ethical consideration

It should be noted that this plan is approved in Torbat Heydariyeh University of Medical Sciences and has the ethics code IR.THUMS.REC.1399.004. The questionnaires were unnamed and the information of the individuals will remain confidential.

Results

We submitted 1148 questionnaires because it was expected that there would be a significant decline in virtual submissions, but only 402 were completed.

In this study, 402 individuals from 28 provinces of Iran participated (Azarbaijan Gharbi, Azarbaijan Sharghi, Alborz, Ardabil, Bushehr, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Esfahan, Fars, Ghazvin, Gilan, Golestan, Hamedan, Hormozgan, Ilam, Kerman, Kermanshah, Khorasan Razavi, Khorasan Shomali, Khuzestan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyerahmad, Kurdistan, Lorestan, Mazandaran, Semnan, Sistan and Baluchestan, Tehran, Yazd, and Zanjan). The highest frequency was related to Tehran (32.3%), Fars (10%), and Khuzestan (7% [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of coronavirus disease-2019 infection in Iranian provinces

| Variable: State of residence | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Alborz | 17 (4.2) |

| Azarbaijan.Gharbi | 4 (1.0) |

| Azarbaijan.Sharghi | 11 (2.7) |

| Ardabil | 19 (4.7) |

| Bushehr | 3 (0.7) |

| Chahar Mahal Bakhtiari | 3 (0.7) |

| Esfahan | 19 (4.7) |

| Fars | 40 (10.0) |

| Ghazvin | 2 (0.5) |

| Gilan | 3 (0.7) |

| Golestan | 1 (0.2) |

| Hamedan | 4 (1.0) |

| Hormozgan | 12 (3.0) |

| Ilam | 5 (1.2) |

| Kerman | 23 (5.7) |

| Kermanshah | 7 (1.7) |

| Khorasan Razavi | 19 (4.7) |

| Khorasan Shomali | 2 (0.5) |

| Khuzestan | 28 (7.0) |

| Kohgiluyeh and Boyerahmad | 13 (3.2) |

| Kurdistan | 3 (0.7) |

| Lorestan | 8 (2.0) |

| Mazandaran | 15 (3.7) |

| Semnan | 1 (0.2) |

| Sistan and Baluchestan | 3 (0.7) |

| Tehran | 130 (32.3) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.7) |

| Zanjan | 3 (0.7) |

| Total | 402 (100.0) |

In this study, among 402 participants with a mean age of 35.7 ± 9.2-year-old, 161 (40%) were male with a mean age of 36.8 ± 9.1, and 239 (59.5%) were female with a mean age of 35.1 ± 9.3. The highest age frequency was related to the participants in the age group of 30–36 years (30.8%). The highest frequency of education levels was related to bachelor's and master's degrees, with a total of 246 (61.2%) people. Two hundred and seventy-three (67.9%) participants were married, 189 (47.0%) were employees, and 388 (96.5%) were residents of the city. Demographic information of the participants is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 161 (40) |

| Female | 239 (59.5) |

| Unknown (not filled) | 2 (0.5) |

| Total | 402 (100) |

| Age | |

| <30 | 92 (23.8) |

| 30-36 | 124 (30.8) |

| 37-40 | 76 (18.9) |

| >40 | 95 (23.6) |

| Unknown (not filled) | 15 (3.7) |

| Total | 402 (100) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 1 (0.2) |

| Elementary school | 8 (2) |

| Middle school | 8 (2) |

| High school | 5 (1.2) |

| Diploma | 43 (10.7) |

| Associate degree | 28 (7) |

| Bachelor degree | 134 (33.3) |

| Master degree | 112 (27.9) |

| Doctoral degree | 43 (10.7) |

| Postdoc degree | 18 (4.5) |

| Unknown (not filled) | 2 (0.5) |

| Total | 402 (100) |

| Marital status | |

| No | 122 (30.3) |

| Yes | 273 (67.9) |

| Other | 3 (0.7) |

| Unknown (not filled) | 4 (1) |

| Total | 402 (100) |

| Job | |

| Student | 11 (2.7) |

| University student | 46 (11.4) |

| Office worker | 189 (47) |

| Manual work | 8 (2) |

| Self-employment | 31 (7.7) |

| Housewife | 53 (13.2) |

| Retired | 9 (2.2) |

| Other | 51 (12.7) |

| Unknown (not filled) | 4 (1) |

| Total | 402 (100) |

| Location residence | |

| City | 388 (96.5) |

| Village | 12 (3) |

| Unknown (not filled) | 2 (0.5) |

| Total | 402 (100) |

The risk perception score obtained from the sum of the scores of the questions was classified into quartiles. Accordingly, the risk perception score of (22.9) 92 people was very low, (26.6) 107 people low, (26.9) 108 people moderate, and (23.6) 95 people high. Multiple linear regression was also used to examine the demographic factors associated with risk perception.

The results showed that the coefficient of determination (R2) in the linear regression model was equal to 0.23. Gender and job variables were also significantly associated with risk perception [Table 3].

Table 3.

That coronavirus disease pandemic risk perception questions during the spring

| Question | Very low, n (%) | Low, n (%) | Medium, n (%) | High, n (%) | Very high, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much do you know about the coronavirus disease transmission cycle? | 7 (1.75) | 8 (1.99) | 115 (28.68) | 182 (45.39) | 89 (22.19) |

| How much knowledge and information do you have coronavirus disease prevention health protocols in shopping and other cases? | 4 (1) | 5 (1.25) | 113 (28.25) | 181 (45.25) | 97 (24.25) |

| How much do you know about the symptoms of coronavirus disease? | 5 (1.25) | 3 (0.75) | 104 (26.07) | 194 (48.62) | 93 (23.31) |

| How effective do you think public health is in preventing coronavirus disease? | 4 (1) | 0 | 13 (3.25) | 112 (28) | 271 (67.75) |

| How effective do you think personal hygiene is in preventing coronavirus disease? | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 7 (1.74) | 98 (24.38) | 294 (73.13) |

| How effective do you think travel avoidance is in preventing coronavirus disease? | 2 (0.5) | 5 (1.25) | 23 (5.74) | 114 (28.43) | 257 (64.09) |

| How effective do you think staying at home is in preventing coronavirus disease? | 3 (0.75) | 0 | 18 (4.5) | 91 (22.75) | 288 (72) |

| How much time did you have to spend away from home working and earning money during this period? | 95 (23.75) | 62 (15.5) | 104 (26) | 81 (20.25) | 58 (14.5) |

| How much do you increase your awareness and knowledge about coronavirus disease prevention during the day? | 17 (4.24) | 35 (8.73) | 153 (38.15) | 144 (35.91) | 52 (12.97) |

| Do you think praying and trusting in god is effective in preventing the coronavirus disease from getting infected or improving patients’? | 90 (22.56) | 44 (10.53) | 96 (24.06) | 72 (18.05) | 99 (24.81) |

| Do you think exercise is effective in preventing coronavirus disease? | 29 (7.21) | 50 (12.44) | 143 (35.57) | 116 (28.86) | 64 (15.92) |

| Do you think fresh fruits and vegetables are effective in preventing coronavirus disease? | 15 (3.74) | 21 (5.24) | 114 (28.43) | 148 (36.91) | 103 (25.69) |

| How much have you participated in gatherings and ceremonies (weddings, mourning, etc.,) in the last month? | 339 (84.96) | 43 (10.78) | 13 (3.26) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| How much do you adhere to the social customs of holy day and parties during this period? | 284 (71.54) | 43 (10.83) | 24 (6.05) | 15 (3.78) | 31 (7.81) |

| How much have you cared about staying home (quarantined) in the last month? | 15 (3.76) | 10 (2.51) | 54 (13.53) | 100 (25.06) | 220 (55.14) |

| How often shared personal supplies did you use at home during this month? | 143 (35.66) | 90 (22.44) | 102 (25.44) | 41 (10.22) | 25 (6.23) |

| How much personal hygiene have you observed in the last month? | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.23) | 33 (8.23) | 154 (38.4) | 211 (52.62) |

| How much have you paid attention to environmental health (outside the home) in the last month? | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1) | 48 (11.97) | 158 (39.4) | 189 (47.13) |

| How much has your in-person purchase been in these days (a recent month)? | 107 (26.62) | 92 (22.89) | 133 (33.08) | 52 (12.94) | 18 (4.5) |

| Has your online shopping increased in recent months due to the coronavirus disease outbreak? | 105 (26.12) | 74 (18.41) | 107 (26.62) | 67 (16.67) | 49 (12.19) |

| How much have you been to the bank these days (a recent month)? | 280 (70) | 85 (21.25) | 26 (6.5) | 5 (1.25) | 4 (1) |

| How much have you used the ATM these days (1 month)? | 200 (49.88) | 115 (28.68) | 67 (16.71) | 10 (2.5) | 9 (2.24) |

| How much have you been cash purchase these days (a recent month)? | 292 (73.18) | 70 (17.54) | 26 (6.52) | 7 (1.75) | 4 (1) |

| How much are you using for shopping from bank card these days? | 69 (17.25) | 77 (19.25) | 83 (20.75) | 58 (14.5) | 113 (28.25) |

| In the last month, how many times have you visited a doctor for signs of coronavirus disease? | 339 (85.39) | 42 (10.58) | 11 (2.77) | 1 (0.25) | 4 (1) |

| Has the outbreak of coronavirus disease caused you to avoid contact with animals? | 79 (19.85) | 22 (5.53) | 39 (9.8) | 78 (19.6) | 180 (45.23) |

| How much of the materials you purchased last month have been disinfected? | 4 (0.995) | 10 (2.5) | 38 (9.45) | 85 (21.14) | 265 (65.92) |

| How much have you disinfect your home, clothes and other supplies in the last month? | 4 (0.995) | 13 (3.23) | 60 (14.93) | 102 (25.37) | 223 (55.47) |

| How much have you been to mosques and shrines in the last month? | 375 (94.46) | 16 (4.03) | 4 (1.01) | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

| Have you visited relatives and acquaintances during the holidays? | 349 (87.91) | 33 (8.31) | 11 (2.77) | 3 (0.76) | 1 (0.25) |

| How much do you use masks and gloves outdoors? | 12 (2.98) | 16 (3.98) | 66 (16.42) | 121 (30.1) | 187 (46.52) |

| How much social distance (minimum one meter and maximum two meters) do you heed with people? | 11 (2.74) | 9 (2.24) | 91 (22.64) | 135 (33.58) | 156 (38.81) |

| How much probability do you have for staying home during time coronavirus disease outbreak? | 25 (6.23) | 21 (5.24) | 85 (21.2) | 129 (32.17) | 141 (35.16) |

| How committed are you to changing your life behavior during the coronavirus disease outbreak? | 4 (1) | 3 (0.75) | 60 (15) | 148 (37) | 185 (46.25) |

| How probable is that a person with coronavirus disease will recover? | 15 (3.75) | 7 (1.75) | 120 (30) | 163 (40.75) | 95 (23.75) |

| How much do you wash your hands properly and thoroughly during the day? | 5 (1.25) | 3 (0.75) | 72 (17.96) | 165 (41.15) | 156 (38.9) |

| How much did you separate your personal supplies from others? | 9 (2.24) | 24 (5.98) | 102 (25.44) | 128 (31.92) | 138 (34.41) |

| How much purchase protocols have you followed in the last month? | 4 (1) | 7 (1.75) | 74 (18.5) | 144 (36) | 171 (42.75) |

| How much do you use personal transportation during this period? | 128 (31.92) | 27 (6.73) | 45 (11.22) | 58 (14.46) | 143 (35.66) |

| How much do you use public transportation (taxis, buses, subways, etc.) during this period? | 332 (83.63) | 26 (6.55) | 24 (6.05) | 7 (1.76) | 8 (2.02) |

| Do you think cash and noncash fines (for people who do not comply with quarantine) are effective in controlling coronavirus disease? | 23 (5.75) | 24 (6) | 56 (14) | 98 (24.5) | 199 (49.75) |

ATM=Automated Teller Machine

The average risk perception score in women was 4 points higher than men (B = 4.234, P = 0.008). The average risk perception score in the employed group was 7 points lower than the housewife and retiree (B = −7.065, P = 0.013).

In addition, with increasing one unit in age, the average risk perception score decreases by 0.1.

There was no significant relationship between risk perception and variables of age, marital status, and level of education (P > 0.05) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Results of multiple linear regression analysis to examine demographic factors related to risk perception

| Predictor | Coefficient | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.091 | 0.350 | −0.281-0.100 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 4.234 | 0.008 | 1.095-7.373 |

| Male | - | - | - |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 2.262 | 0.219 | −1.354-5.878 |

| Single | - | - | - |

| Education | |||

| Diploma | −1.406 | 0.727 | −9.304-6.493 |

| academic education | −0.100 | 0.977 | −6.835-6.635 |

| High school | - | - | - |

| Job | |||

| Student | 3.814 | 0.169 | −9.260-1.632 |

| Office worker | 0.292 | 0.877 | −3.991-3.407 |

| Factory worker andself-employed | −7.065 | 0.013 | −12.657-−1.473 |

| Housewife and retiree | - | - | - |

Coefficient=Regression coefficient, P=P-value for the regression coefficient. CI=Confidence interval for the regression coefficient, Bold=Statistically significant

Discussion

Risk perception is important in making the right decisions during a pandemic crisis, and it can be said that it is the stimulus of preventive behaviors.[13] If people have a good risk perception, they will use control devices because they value avoiding disease (according to HBM model).[14] This study was conducted to assess the risk perception of the coronavirus risk in spring in Iran. In this study, 402 individuals from 28 provinces in Iran participated (90% provinces of Iran). The results of the risk perception survey in 10 countries from different continents, i.e., Europe, Asia, and America, have shown that personal experience of coronavirus infection, personal and social value, friends and family, trust in government, science, medical professionals, personal knowledge of government strategy, and individual and collective effectiveness were all significant predictors of risk perception.[15]

Furthermore, the results of the study by Samadipour and Ghardashi indicate that religious, cultural, political, cognitive, social, and emotional factors were effective in Iranians’ risk perception of COVID-19.[7] According to the results of this study, 86.25% of the participants believed that survival and recovery from the coronavirus are possible, 76.62% of participants used masks and gloves outdoors, and 72.39% of participants had observed the social distancing. In addition, 98.01% of the people washed their hands correctly and completely. It may be a result of Iranian religious attitude that people should be hopeful and try keeping their bodies safe and clean.

The results of the study showed that 66.92% of the people stated that praying and trusting in God is effective in preventing the coronavirus or improving the disease, but 98.5% responded that they have not been to mosques and shrines in the last month. The results of the study by Samadipour and Ghardashi showed that religious and cultural factors were mostly associated with Iranians’ risk perception.[7] A study by Chester et al. showed that religion and other religious beliefs play effective roles in understanding and managing the risk.[16]

In our study, 88% of the participants responded, a person infected with coronavirus may not show or report symptoms. Hence, lots of them conduct in a preventive manner. Our study results were the same as Kwok et al. study that showed more than 70% of the people of Hong Kong observed personal hygiene and travel avoidance in the 1st week of the emergence of coronavirus. However, the actual acceptance of social distancing has been less.[8] The results of the study by de Bruine et al. reported out of 6684 respondents, 90% reported handwashing, 58% avoiding high-risk individuals, 57% avoiding crowds, and 37% canceling or postponing travel.[17] In Rezaeipandari study et al. (2018), among the preventive behaviors of influenza A, the highest frequency was related to continuous washing of hands by soap and water, covering the mouth and nose when coughing and sneezing, and the least frequency was wearing the masks when leaving the house.[18] The results of studies by Alizadeh, Shilpa, and Kamate indicated the most frequent preventive behaviors related to handwashing.[19,20,21]

The results of the studies showed that acceptance of preventive behaviors had a significant relationship with risk perception, and this is more important in the coronavirus pandemic.[12,15] Although respondents in the United States strongly disagreed on the risks of COVID-19, risk perception has generally been associated with protective behaviors.[17] The results of a study conducted in the Netherlands on the SARS epidemic showed that there was a correlation between risk perception and preventive behaviors.[22] While in the study of Taghrir et al. on medical students, a significant negative correlation was reported between preventive behaviors and risk perception, and the perception of risk is associated with stress and anxiety and the perception of risk decreases as stress reduces.[23] It may be because of insufficient personal protective devices and unreasonable stress relief based on unreliable news. The statistical results of a risk perception study in Vietnam showed that two factors, i.e., the use of social media and geography, were effective in risk perception. The higher use of social media, the greater the perception of risk, and the people of central and south Vietnam were more aware of the risk than the regions of North Vietnam because the first cases were reported in these areas.[24] According to the findings of this study, 87.03 of people tried to increase their awareness and information about the prevention of coronavirus during the day. The information level of 96.26% of participants was moderate to high about the coronavirus transmission cycle. In addition, the level of knowledge and information about purchase protocols and other hygienic standards in the prevention of coronavirus was moderate to high in 97.75% of the participants. Moreover, 48.62% of participants were aware of symptoms of coronavirus.

According to the results of the study by Rezai Pendri et al. on preventive behaviors in the outbreak of influenza type A, a positive correlation between behavior and level of awareness of benefits and severity of perceived risk has been reported. In the study of Taghrir et al., the results showed that 79.60% of medical students had a high level of knowledge related to coronavirus. The mean rate of preventive behaviors was 94.47% and 94.2% had high performance in preventive behaviors.[23] The preventive health behaviors are not only determined by the awareness of objective health risks but also influenced by health beliefs and cognitions, which is consistent with the results of the study of Zera et al.[25,26]

Based on the results of the research conducted in the United States, the risk perception of COVID-19 and the one of death due to COVID-19 has a stronger relationship with protective behaviors because it was understood that COVID-19 may have severe consequences other than death including serious diseases and self-quarantine.[16] In the 1st year of the H1N1 flu epidemic, the perception of infection risk with vaccination was more strongly correlated than the perception of mortality risk from influenza.[27] However, the results of a cross-sectional study in Asian or European regions showed no significant relationship between understanding the risk of the flu pandemic and performing protective behaviors at the time of the outbreak.[28] The results of this study showed that 67.75% of participants agreed that observing public health and 73.13% of participants agreed that personal hygiene is very effective in preventing coronavirus. About 64.09% of participants believed that avoiding travel can be very effective in preventing coronavirus infection. Tehran is the country's business hub, and the city has a high population density, resulting in peaks in demand for practically every mode of public transportation, including ridesharing taxis, metro, and bus. There are no limitations or alternate forms of transport put in place to reduce the population in high-risk high traffic areas and transport means.

In the US, 37% of people canceled or postponed travel by the start of the coronavirus epidemic.[17] In our study, 72.0% of participants believed that staying at home can be very effective in preventing coronavirus infection. According to the results of the study, factors affecting the understanding of the coronavirus risk by Samadipour and Ghardashi such as hygiene and implementation of health protocol had the highest positive correlation with the risk perception model.[7]

According to the results of the current study, people had participated very little in gatherings, weddings, and funerals, etc., in the last month. The adherence rate to the social customs of Nowruz and parties during this period has been very low. In the last month, 55.14% of participants were quarantined. The results of other similar studies have shown that ignoring coronavirus power has the most negative correlation with the risk perception model.[7]

Among other health behaviors, we can name disinfection of home surfaces, disinfection of purchased items, reduction of visits to banks, ATMs, mosques, and shrines, reduced party and visits during the New Year, observance of quarantine, and reduced use of public transportation.

The reason could be aware of the symptoms and ways of prevention during the pandemic, which was available to the public through different sources and led to increased awareness.

Hence, continuing the training of preventive health behaviors can play an important role in creating healthy behaviors in society.

In the current study, the results showed that 49.75% of participants believed that cash and noncash fines have a great impact on individuals, who do not observe the quarantine standards of the home. Other studies also show the role of the government in coronavirus control and strict rules impact on the implementation of health protocols.[29] The results of the study showed that 60.75% of the responder have to stay out of the house to work and earn money. Hence, in the pandemic, people need governmental economic support.

According to the result, risk perception is effective in accepting health protocols and adopting preventive behaviors; therefore, raising awareness and promoting risk perception in the community is especially important in the coronavirus pandemic. The result of this study shows a picture of risk perception in Iranian people during COVID-19 for the first time, and it can be beneficial for planning in health promotional education.

The level of risk perception in the public people reflects the impact of education and information on culture building at the community level, and indirectly indicates the level of compliance with protocols. Awareness of perceived risk can be included in management decisions to strengthen or change prevention and health promotion programs.

Recommendation and limitation

One of the limitations of this study is that samples were collected only in spring (the beginning of the Corona pandemic). It cannot be generalized to the whole pandemic duration. Furthermore, data were collected through a virtual questionnaire and only literate people and those who had access to Internet could have participated. We tried several times, but just 402 participants answered the questionnairs. The questionnaire was distributed into social media.

Another limitation of this study was the collection of data were collected at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, in which there was little knowledge about coronavirus.

Furthermore, this study was conducted in Iranian people under the cultural and social conditions of Iran. Therefore, its generalization of the results to other times during the coronavirus pandemic and other societies may not be possible.

Conclusion

It seems that the level of risk perception of those, who had access to this questionnaire, was moderate to high. These results may be due to preventive measures to control COVID-19 by governmental and nongovernmental organizations In Iran. Furthermore, since the beginning of the pandemic, virtual webinars were held for medical staff and 24-h call centers to answer people's questions. The results of the study showed that many of the participants have to go out to work and earn money. Hence, in the pandemic, workers need governmental economic support. Examining the risk perception of a pandemic can help preventive measures and planning, and also according to the results of the research can be done appropriate educational interventions. Given that 47.5% of respondents were employees, presenting the results of the study can be useful in making prevention decisions and maintaining safety and health in the workplace.

According to the results of this study, a large percentage of people had to leave home to earn money, so it is suggested that work at home and home production be more supported. The results of our study may be generalizable to Islamic countries with similar cultures and customs to Iran.

Financial support and sponsorship

Torbat Heydaiyeh University of Medical Sciences (cod No; 99000012).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to Torbat Heydaiyeh University of Medical Sciences for financial support (cod No; 99000012).

References

- 1.Ghalichi Z, Barzanouni S, Pirposhteh E.A, Pouya Ab, Poursadeghian M, Hami M. A Study of Preventive Behaviors Against COVID-19 in the Lifestyle of Iranian Society of in Iran after one Years of Pandemic. JOHE. 2022 11,1, X. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khajehnasiri F, Zaroushani V, Poursadeqiyan M. Macroergonomics and health workers during COVID-19 pandemic. Work. 2021;69:713–4. doi: 10.3233/WOR-210412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soltaninejad M, Babaei-Pouya A, Poursadeqiyan M, Feiz Arefi M. Ergonomics factors influencing school education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review. Work. 2021;68:69–75. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu K, Cai H, Shen Y, Ni Q, Chen Y, Hu S, et al. Management of corona virus disease-19 (COVID-19): The Zhejiang experience. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;49:147–57. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poursadeqiyan M, Kasseri N, Pouya AB, ghalichi-zaveh Z, Abbasi M, Khajehnasiri F, et al. The fear of COVID-19 infection after one years of jobs reopening in Iranian society. J Health Sci Surveillance Sys. 2022;10 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dargahi A, Gholizadeh H, Poursadeghiyan M, Hamidzadeh Y, Hamidzadeh MH, Hosseini J. Health-promoting behaviors in staff and students of Ardabil University of Medical Sciences. J Edu Health Promot. 2022;9 doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1639_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samadipour E, Ghardashi F. Factors influencing Iranians’ risk perception of COVID-19. J Mil Med. 2020;22:122–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwok KO, Li K K, Hin Chan H H, Yuan Yi Y, Tang A, Wei WI, et al. Community responses during the early phase of the COVID-19 epidemic in Hong Kong: Risk perception, information exposure and preventive measures. medRxiv. 2020;26(7):1575–1579. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddux JE, Rogers RW. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1983;19:469–79. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosa EA. White, Black, and Gray: Critical Dialogue with the International Risk Governance Council's Framework for Risk Governance, in Global Risk Governance. Germany: Springer; 2008. pp. 101–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li JB, Yang A, Dou K, Wang LX, Zhang MC, Lin XQ. Chinese public's knowledge, perceived severity, and perceived controllability of COVID-19 and their associations with emotional and behavioural reactions, social participation, and precautionary behaviour: A national survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1589. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wise T, Zbozinek TD, Michelini G, Hagan CC, Mobbs D. Changes in risk perception and self-reported protective behaviour during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. R Soc Open Sci. 2020;7:200742. doi: 10.1098/rsos.200742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cori L, Bianchi F, Cadum E, Anthonj C. Risk Perception and COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;19(19):3114. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rejeski WJ, Fanning J. Models and theories of health behavior and clinical interventions in aging: A contemporary, integrative approach. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1007–19. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S206974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dryhurst S, Schneider C.R, Kerr J, Freeman A L. J, Recchia G, van der Bles A.M. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J Risk Res. 2020;23:994–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chester DK, Duncan AM, Dibben CJ. The importance of religion in shaping volcanic risk perception in Italy, with special reference to Vesuvius and Etna. J Volcanol Geothermal Res. 2008;172:216–28. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruine de Bruin W, Bennett D. Relationships between initial COVID-19 risk perceptions and protective health behaviors: A national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59:157–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rezaeipandari H, Mirkhalili S.M, Morowati Sharifabad M.A, Ayatollahi J, Fallahzadeh H. Investigation of predictors of preventive behaviors of influenza A (H1N1) based on health belief model among people of Jiroft City, (Iran) 2018;12(3):76–86. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alizadeh K, Zareiy S, Hoseini Y. H1N1 influenza among suspected patients in Bes’ at IRIAF hospital Nov and Dec 2009: A case-series. Ebnesina. 2010;12:26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shilpa K, Praveen Kumar BA, Yogesh Kumar S, Ugargol Amit R, Naik Vijaya A, Mallapur MD. A study on awareness regarding swine flu (influenza A H1N1) pandemic in an urban community of Karnataka. Med J Dr. DY Patil Univ. 2014;7:732–737. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamate SK, Agrawal A, Chaudhary H, Singh K, Mishra P, Asawa K. Public knowledge, attitude and behavioural changes in an Indian population during the Influenza A (H1N1) outbreak. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;4:7–14. doi: 10.3855/jidc.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brug J, Aro AR, Oenema A, de Zwart O, Richardus JH, Bishop GD. SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1486–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1008.040283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taghrir MH, Borazjani R, Shiraly R. COVID-19 and Iranian medical students; A survey on their related-knowledge, preventive behaviors and risk perception. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23:249–54. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huynh TL. The COVID-19 risk perception: A survey on socioeconomics and media attention. Econ Bull. 2020;40:758–64. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renner B, et al. Risk perception, risk communication and health behavior change: Health psychology at the University of Konstanz. Zeitschrift Für Gesundheitspsychol. 2008;16:150–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zera CA, Nicklas JM, Levkoff SE, Seely EW. Diabetes risk perception in women with recent gestational diabetes: Delivery to the postpartum visit. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:691–6. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.746302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gidengil CA, Parker AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Trends in risk perceptions and vaccination intentions: A longitudinal study of the first year of the H1N1 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:672–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadique MZ, Edmunds WJ, Smith RD, Meerding WJ, de Zwart O, Brug J, et al. Precautionary behavior in response to perceived threat of pandemic influenza. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1307–13. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.070372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kupferschmidt K, Cohen J. China's aggressive measures have slowed the coronavirus. They may not work in other countries. Science. 2020;2:3193. [Google Scholar]