Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Since poor communication with the patient has a negative impact on the quality of nursing care, taking the necessary measures to strengthen the relationship with the patient seems necessary. This study was conducted to determine the effect of spiritual intelligence training on nurses’ skills for communicating with patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This experimental study with the control group and the pretest-posttest design was conducted on 70 nurses working in Imam Khomeini Hospital, Mahabad, in 2019. Randomized stratified sampling was used to recruit participants. Then, participants were randomly assigned to the two groups of control and intervention. The demographic information form and the patient-nurse communication skill questionnaire were used to collect the data. For the intervention group, 7 spiritual intelligence training sessions were held as a workshop in 2 months. Two weeks and a month after the intervention, both groups completed the questionnaires. Data were analyzed with the SPSS software version 17.0.

RESULTS:

The findings showed that the mean communication skill scores in the intervention group before training were 44.71 ± 7.62, which significantly increased to 66.22 ± 8.43 2 weeks after training. Bonferroni multiple comparisons showed the mean communication skill scores significantly increased before, 2 weeks later and in the follow-up phase in the intervention group (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION:

Spiritual intelligence training is effective in improving the communication skills of nurses. It is recommended that the prepared content can be provided to in-service training units; consequently, nurses can improve their communication skills by individual and group learning.

Keywords: Communication, intelligence, nurse, patient, spirituality

Introduction

Communication has always been one of the most challenging issues in nursing.[1] Proper communication by nurses leads to better understanding of the patient's concerns; provides empathy and support; improves the patient's mental, physical, and psychological well-being.[2]

Spiritual intelligence is a human capacity to search and ask the ultimate questions about the meaning of life, and at the same time, it is the experience of the integrated connection between each of us and the world in which we live.[3] George considers the important features of spiritual intelligence to be personal confidence, the effectiveness of communication, interpersonal understanding, managing changes, and moving from difficult routes.[4] Besides, from King's point of view, the four main components of spiritual intelligence include critical existential thinking, personal meaning production, transcendental consciousness, and the development of the state of consciousness.[5]

Having high spiritual intelligence helps medical staff to cope better with work pressures by considering the services they provide to patients and society as meaningful and purposeful.[6] However, in a study in Iran in 2011, spiritual intelligence was lower than the mean score in 45% of nurses.[7]

Teaching communication skills to nurses increase the quality of patient care.[7] Training program based on BASNEF Model in improving nursing interpersonal communication skills[8] and spiritual care skills training.[9] Thus, the role of spiritual intelligence is significant in the way nurses communicate.[10]

Despite the importance of effective communication, research has shown that communication between nurses and patients in Iran has not been very effective and has been reported to be weak in many cases.[11] Rostami et al.'s study assessed nurses’ communication skills as poor.[12] Since poor communication with the patient has a negative impact on the quality of nursing care, taking the necessary measures to strengthen communication with the patient seems essential. The present study was carried out with the aim of determining the effect of spiritual intelligence training on nurses’ skills for communicating with patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This is an experimental study with a control group and the pretest-posttest design that was conducted on 70 nurses of Imam Khomeini Hospital, Mahabad, in 2019.

Study participants and sampling

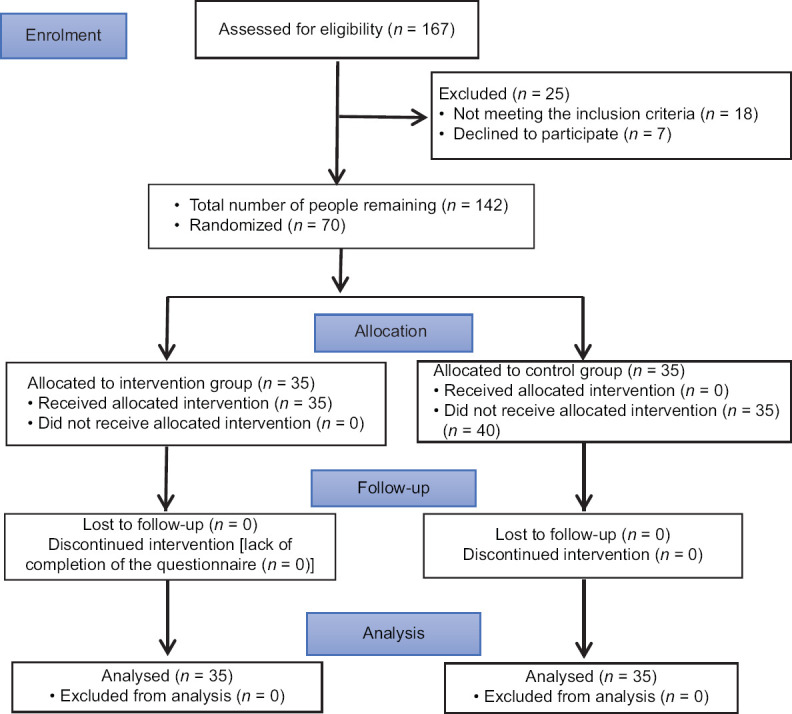

Our target population was nurses working in Imam Khomeini Hospital. Nurses were stratified according to wards and randomly assigned as control group (n = 35) and intervention group (n = 35). The sample size was calculated according to the study by Massoud et al.,[13] in which the mean and standard deviation of the total score of communication skills in the control and the intervention groups were 99.9 ± 15.1 and 114.5 ± 14.3, respectively, with 95% confidence and 95% test power in the formula  . Taking into account, the 10% attrition, 35 individuals for each group, and a total of 70 participants entered the study [Figure 1].

. Taking into account, the 10% attrition, 35 individuals for each group, and a total of 70 participants entered the study [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the participants

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included the willingness to participate in the study, having at least a bachelor's degree in nursing, not participating in the spiritual intelligence and communication skills workshops in the past 6 months, and having at least 6 months of clinical nursing experience. Exclusion criteria included the unwillingness to stay in the study, absence from more than one session of training and leaving the hospital, or being transferred to another hospital.

Data collection

Data were collected using a two-part questionnaire. The first part was related to demographic information, including age, gender, level of education, marital status, income, employment ward, work experience, and employment status. The second part was the nurse-patient communication skills questionnaire. This tool was designed by Hemmati-Maslakpak et al. The tool consists of 21 phrases arranged in two areas: verbal (13 phrases) and nonverbal (8 phrases) skills of communicating with the patient. The scale used in this measurement is Likert, in which each item contains five degrees of evaluation from always to ever, and the values of each item vary between 1 and 5. The sum of the numerical values of the items indicates the measurement score that fluctuates between 21 and 105. In determining the scoring rate, three levels are assumed: scores 21–49 indicating poor communication with the patient, scores 50–77 indicating moderate communication with the patient, and scores 78–105 indicating a good relationship with the patient.[14]

Hemmati-Maslakpak et al. used the qualitative and quantitative content validation method to determine the scientific validity of the questionnaire after its face validity was approved by 15 samples. After confirming the content validity of the questionnaire by 10 experts, they used content validity ratio, content validity index, and 15 experts’ ideas to determine the quantitative content validity. The reliability coefficient of the questionnaire was determined as 0.96 using the test-retest method. Furthermore, the reliability of its aspects was confirmed by Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.87 and 0.92 for verbal and nonverbal skills, respectively.[14]

Procedure

First, we obtained permission from the research and ethics committee of Urmia University of Medical Science (IR.UMSU.REC.1398.058) and registering in the IRCT system with the code: (IRCT06626662616102N4). Then, the researcher referred to Imam Khomeini Educational and Medical Center in Mahabad to coordinate with hospital officials and conduct the research. First, the list of all 12 wards of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Mahabad was prepared. Afterward, the wards’ name was written on separate sheets and placed in a bag, and by drawing lots (simple random), six wards including Men's Internal Medicine ward, Women's Surgical ward, Dialysis, Neuroscience Intensive Care Unit (NSICU), Emergency Unit, and Critical Care Unit (CCU) were selected. In the second stage of the drawing lots, by simple random method, wards were assigned to the control and the intervention group successively (Emergency Unit, CCU, and Women's surgical ward for the intervention group and dialysis unit, NSICU, and Men's Internal Medicine ward for the control group). Subsequently, a list of employed nurses in the selected wards, who were qualified to enter the study, was prepared and subjects were selected using the simple random method and in proportion to the number of nurses in each ward (Emergency Unit – 21 participants, CCU – 6 participants, Women's Surgical ward – 8 participants, NSICU – 19 participants, Dialysis – 7 participants, and Men's Internal Medicine – 9 participants). If any selected subject was reluctant to participate in the study, the next sample was randomly selected and replaced [Figure 1].

The researcher introduced himself to the subjects and obtained informed consent from them. After stating the research objectives, the number of sessions, and the time and manner of holding the sessions, the members of the intervention group were asked to strictly refrain from exchanging any information with the control group and other nurses according to the research objectives. The questionnaires were unnamed, and nurses were assured that the respondents’ information would remain confidential and would only be used for research purposes and that the results of the study would be provided to them if desired. Later, the training of spiritual intelligence was held for the intervention group as a workshop in 7 sessions of 90 min with an interval of 1 week. No training was given to the control group.

Meetings were held every Thursday from 8:30 to 10 a.m. in the conference hall of Imam Khomeini Hospital. Educational protocols were selected based on spiritual intelligence training sessions from King's point of view. The educational content of the meetings has been described in Table 1. In addition, in the intervals between the sessions, the researcher tried to recall the content and motivate the participants to cooperate more by using SMS and social media and answered the nurses’ questions during and after the intervention sessions. Two weeks and 1 month after the completion of the educational intervention, the nurse-patient communication skill questionnaires were completed by the two intervention and control groups.

Table 1.

Content of spiritual intelligence training sessions from King’s point of view

| Session | Subject |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | Introducing members to each other, announcing group rules, defining and explaining spirituality and spiritual intelligence, raising a few questions to discuss |

| Session 2 | Familiarizing with the application of spirituality in everyday life and spiritual intelligence from King’s point of view, the benefits of spiritual intelligence and its components, explaining the concept of flexibility and familiarizing with this concept |

| Session 3 | Teaching the first component of the intellectual intelligence from King’s point of view: “Critical Thinking” including thinking capacity about the nature of the universe and existence of self, life goals and reasons, thinking about the meaning of life events, defining honesty and rightness |

| Session 4 | Teaching the second component of the spiritual intelligence from King’s point of view: “Producing personal meaning” including the individual’s ability to understand the meaning and purpose of life to overcome stressful situations, the ability to understand the meaning of life goals and reasons |

| Session 5 | Teaching the third component of the spiritual intelligence “transcendent consciousness” including transcendent consciousness as a state beyond the natural and physical experience of the human being or the existential nature without the main limitations in the material world, knowing and being aware of the immaterial aspects of life, mindfulness in the inner and outer world |

| Session 6 | Teaching the fourth component of the spiritual intelligence “Expansion and increase of conscious state” including explanations and practice on methods of expanding states of consciousness (pondering and thinking, exploring) - how to meditate and practice - mindfulness and practice, the definition of sleep and its application in life |

| Session 7 | Reviewing the topics of previous sessions and summarizing the contents and answering the participants’ questions, appreciating the subjects’ participation |

Data analysis

To interpret the statistical results, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 17 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) was used. To compare the means, the repeated measurement was used at three points of time, i.e., before the intervention, 2 weeks, and 1 month after the intervention. In addition, Bonferroni Multiple Comparisons were used to compare the mean of intragroup total communication skills in the control and intervention groups. Data normality was also analyzed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. The significant level was considered as P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The majority of participants in this study were female (68.6%), single (60%), with <5 years of work experience (45.7%), and with the age mean of 35.26 ± 7.14 and 31.60 ± 5.76 in the intervention and control groups, respectively. In addition, the mean and standard deviation of the work experience of the intervention group and the control group were 10.29 ± 6.88 and 7.23 ± 5.76, respectively. Based on the results, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of these variables. In other words, the two groups were completely identical (P > 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the three study groups

| Variable | n (%) | n (%) | df | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 20-29 | 16 (45.7) | 9 (25.7) | 2 | 0.156 |

| 30-39 | 15 (42.9) | 17 (48.6) | ||

| 40-49 | 4 (11.4) | 9 (25.7) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 11 (31.4) | 12 (34.3) | 1 | 0.799 |

| Female | 24 (68.6) | 23 (65.7) | ||

| Educational | ||||

| Masters | 28 (80) | 29 (82.9) | 1 | 0.759 |

| Masters | 7 (20) | 6 (17.1) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 14 (40) | 18 (51.4) | 1 | |

| Single | 21 (60) | 17 (48.6) | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Design | 10 (28.6) | 6 (17.1) | 3 | 0.679 |

| Contract | 3 (8.6) | 2 (5.7) | ||

| Official | 16 (45.7) | 20 (57.1) | ||

| Company | 6 (17.1) | 7 (20) | ||

| Income | ||||

| Income = expenditure | 4 (11.4) | 6 (17.1) | 2 | 0.136 |

| Input > expenses | 6 (17.1) | 1 (2.9) | ||

| Income < expenditure | 25 (71.4) | 28 (80) | ||

| Work experience | ||||

| 1-5 | 16 (45.7) | 13 (37.1) | 4 | 0.215 |

| 6-10 | 11 (31.4) | 5 (14.3) | ||

| 11-15 | 4 (11.4) | 9 (25.7) | ||

| 16-20 | 2 (5.7) | 4 (11.4) | ||

| >21 | 2 (5.7) | 4 (11.4) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Age (mean±SD, years) | 31.60 (5.932) | 35.26 (7.147) | 68 | 0.642 |

| Work experience | ||||

| Age (mean±SD, years) | 7.23 (5.765) | 10.29 (6/888) | 68 | 0.130 |

SD=Standard deviation, df=Degrees of freedom

Nurse-patient communication

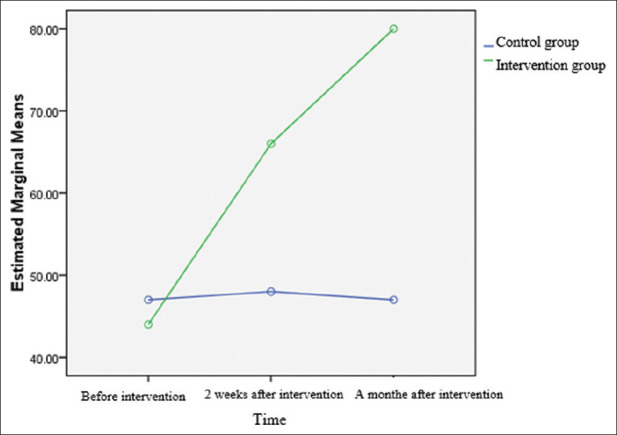

The mean scores of verbal communication skills before the intervention and 2 weeks and 1 month after the intervention in the intervention group were 28.20 ± 5.87, 41.85 ± 6.10, and 51.54 ± 4.57, respectively, and in the control group were 30.34 ± 4.41, 30.82 ± 4.33, and 30.2 ± 5.70, respectively. Mean scores of nonverbal communication skill scores before the intervention and 2 weeks and 1 month after the intervention in the intervention group were 16.51 ± 3.32, 24.37 ± 5.59, and 29.11 ± 4.49 and in the control group were 17.20 ± 4.35, 17.82 ± 4.36, and 17. 77 ± 4.87, respectively. In addition, the mean scores of total communication skills before the intervention and 2 weeks and 1 month after the intervention in the intervention group were 44.71 ± 7.62, 66.22 ± 8.43, and 80.65 ± 7.63 and in the control group were 47.54 ± 6.01, 48.65 ± 6.58, and 47.80 ± 8.74, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of the communication skills in the study groups at 3 points of time

| Group | communication skills | Before intervention | 2 weeks after the intervention | 1 month after the intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Verbal | 30.34±4.41 | 30.82±4.33 | 30.02±5.70 |

| Nonverbal | 17.20±4.35 | 17.82±4.36 | 17.77±4.87 | |

| Total | 47.54±6.01 | 48.65±6.58 | 47.80±8.74 | |

| Intervention | Verbal | 28.20±5.87 | 41.85±6.10 | 51.54±4.57 |

| Nonverbal | 16.51±3.32 | 24.37±5.59 | 29.11±4.49 | |

| Total | 44.71±7.62 | 66.22±8.43 | 80.65±7.63 |

Repeated measures analysis was used to evaluate the mean score of total communication skills at 3 points of time between the control and the intervention groups. The results are shown in Table 4. In this table, three effects are tested: (1) The interaction effect of time and intervention: the result of the statistical test indicates that the interaction effect of time and intervention on the mean scores of total communication skills is significant (P < 0.001), in fact, the response trend (total communication skills scores) is not the same for both groups over time, (2) time effect: due to the fact that the value of the variable of time is <0.05; therefore, the assumption that the different levels of time factor are the same is rejected with maximum confidence of 0.99. Accordingly, a statistically significant difference was observed in the mean scores of total communication skills at different points of time (P < 0.001), (3) the main effect of the intervention: the main purpose of this study is to investigate this effect and the results of the table of variance analysis show that there is a significant difference between the intervention and control group (P < 0.001) in the mean trend of total communication skills [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of the communication skills between the study groups at 3 points of time

| Total communication skills score | Total squares of error | df | Average square error | F | P | Partial eta squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original effect (time) | 11,466.35 | 1 | 11,466.35 | 223.13 | <0.001 | 0.766 |

| Mutual effect (with intervention) | 11,142.86 | 1 | 11,142.86 | 216.84 | <0.001 | 0.761 |

| Error component (time) | 3494.28 | 68 | 51.38 | - | - | - |

| The main effect (intervention) | 13,216.93 | 1 | 13,216.93 | 125.95 | <0.001 | 0.640 |

| Error component (intervention) | 7135.46 | 68 | 104.93 | - | - | - |

df=Degrees of freedom

As shown in Figure 2, at first, the mean of both groups was almost similar, and in the control group, over the next period, the means were almost alike and were not significantly different. However, in the intervention group, the mean score increased over the next period, and due to this increase, it was significantly different from that of the control group.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the communication skills between the study groups at 3 points of time

Multiple comparison

Given that the interaction effect of time and intervention is significant, the comparison of the mean of total communication skills between the intervention and control groups in different points of time is evaluated as the intervention effect. The results are summarized in Table 5 in the Bonferroni Multiple Comparison method. Before the intervention, the mean of total communication skills in the two groups was not significantly different (P = 0.089) that indicates the similarity of total communication skills of the two groups before the study. However, in the changes of the mean scores of total communication skills in the two groups, significant differences were observed 2 weeks and 1 month after the intervention (P < 0.001) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Comparison of the communication skills between the groups in different points of time as the intervention effect

| Time | Group | Average difference | The difference between the SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | Intervention-control | 2.82 | 1.64 | 0.089 |

| 2 weeks after the intervention | Intervention-control | −17.57 | 1.80 | 0.001 |

| 1 month after the intervention | Intervention-control | −32.85 | 1.96 | 0.001 |

SD=Standard deviation

Moreover, to compare the mean of intragroup total communication skills in the control and intervention groups, Bonferroni Multiple Comparisons were used [Table 6].

Table 6.

Comparison of the mean of intragroup total communication skills in study groups

| Group | Time | Mean difference | SD difference | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Before versus 2 weeks after | −1.11 | 1.26 | 1.000 |

| Before versus a month after | −0.25 | 1.71 | 1.000 | |

| 2 weeks later versus 1 month after | 0.85 | 1.09 | 1.000 | |

| Intervention | Before versus 2 weeks after | −21.51 | 1.26 | 0.001 |

| Before versus a month after | −35.94 | 1.71 | 0.001 | |

| 2 weeks later versus 1 month after | −14.42 | 1.09 | 0.001 |

SD=Standard deviation

In the intervention group, the mean scores of total communication skills before the intervention were different from 2 weeks and 1 month after the intervention; in addition, the mean scores of total communication skills 2 weeks and 1 month after the intervention were significantly different (P < 0.001). Furthermore, in the control group, the mean scores of communication skills before the intervention, 2 weeks, and 1 month after the intervention were not significantly different. In other words, in the intervention group, after the intervention, the total communication skills scores increased; therefore, the intervention was effective.

Discussion

This study showed that the mean of total communication skills and the two components of communication including verbal and nonverbal communication in nurses of the intervention group were significantly higher than those of nurses in the control group. In other words, the intervention of spiritual intelligence training has been effective in improving the communication skills of nurses in the intervention group.

This result is consistent with the results of the study by Kaur et al. conducted in Malaysian hospitals. The results of the above-mentioned study showed that spiritual intelligence training has significant effects on nurses’ care behaviors.[15] Bagheri et al. conducted on nursing students in Bushehr are in agreement with the present study. The results of the aforementioned study showed that the promotion of spiritual intelligence through religious education leads to an understanding of life patterns, greater achievement of communication skills, and proficiency in goal setting.[16]

In line with the findings of the present study, we can point to the results of the study by Rani et al. In that case study, the effect of spiritual intelligence training on nurses’ performance was evaluated as positive. Quoted from several studies, they believe that spiritual intelligence helps nurses feel good, contented, and look at problems correctly.[17] A study by Abolfazl, 2013 showed that spiritual intelligence can predict the effectiveness of employees’ relationships. Communication skills are likewise able to predict this effectiveness.[18]

The results of the study by Ghasemi et al. who examined the relationship between spiritual intelligence and communication skills of nursing students in a descriptive-correlational study showed that spiritual intelligence has a positive relationship with communication skills. That is to say, individuals with high spiritual intelligence listen well to others, accept them, and interact well with them.[19] It is consistent with the present study. In his study, Emmons sought to answer the question of whether spirituality is considered a form of intelligence. He believes that spirituality predicts the performance and level of adaptation of individuals and also provides the necessary facilities to solve problems and achieve goals.[20]

The results of Heydari et al.'s study, which was conducted to determine the effect of spiritual intelligence training on job satisfaction of nurses working in Mashhad Psychiatric Hospital, showed that the mean scores of job satisfaction in the intervention group were higher than the control group and in follow-up stage 1 month later, the mean of job satisfaction in the intervention group was higher than before.[21]

Since there were a limited number of similar studies to compare the effect of spiritual intelligence training on nurses’ skills for communicating with patients, the findings of the present study were compared with studies aimed at determining the effect of other educational interventions on nurses’ communication skills. In line with the findings of the present study, the results of the study by Kounenou et al. indicated that there was a significant difference in the nurses’ skills for communicating with patients among nurses who participated in seminars and conferences on communication and those who did not participate.[22] Similarly, in the study by Xie et al., nurses and nursing students who were trained in communication skills through speech had higher communication skills,[23] which are consistent with the results of the present study. However, in Salimi et al.'s study, no significant relationship was observed between taking interpersonal communication skills training courses and the level of communication skills of nursing students.[24] The difference could be due to different educational environments and discrepancies in the quality of teaching.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this study was that the study population was nurses of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Mahabad; therefore, the generalization of results to other populations should be done with caution. Due to the selection of the intervention and control groups from a hospital, there was a possibility of transferring information. To reduce this error, the intervention group was asked to refrain from giving information and training provided in meetings to the control group. Moreover, differences in mental and spiritual characteristics, motivations, and the personality traits of the participants might have affected their perception and knowledge.

Conclusion

Recent findings suggest that workshop-based spiritual intelligence training has been relatively successful in improving nurses’ communication skills. Although the effect of education in any way possible is obvious for individuals with various characteristics, teaching in different ways has different results. Therefore, it is recommended that the prepared content can be provided to in-service training units; consequently, nurses can improve their communication skills by individual and group learning.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study has been extracted from a master's thesis in medical-surgical nursing and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Urmia University of Medical Sciences (Approval No. IR.UMSU.REC.1398.058). The authors express their deep gratitude to the university officials and the participants for the contribution they have made.

References

- 1.Li Y, Wang X, Zhu XR, Zhu YX, Sun J. Effectiveness of problem-based learning on the professional communication competencies of nursing students and nurses: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2019;37:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgener AM. Enhancing communication to improve patient safety and to increase patient satisfaction. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2020;39:128–32. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pant N, Srivastava SK. The impact of spiritual intelligence, gender and educational background on mental health among college students. J Relig Health. 2019;58:87–108. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George M. How intelligent are you. really? From IQ to EQ to SQ, with a little intuition along the way. Train Manage Dev Methods. 2006;20:411–25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.King DB, DeCicco TL. A viable model and self-report measure of spiritual intelligence. Int J Transpers Stud. 2009;28:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bone N, Swinton M, Hoad N, Toledo F, Cook D. Critical care nurses’ experiences with spiritual care: The SPIRIT study. Am J Crit Care. 2018;27:212–9. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2018300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mingaghi K, Gazranani A, Real S, Gholami H, Moghaddam S, Assyrian A. The relationship between spiritual intelligence and clinical competence. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2011;10:132–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nazari S, Jalili Z, Tavakoli R. The effect of education based on the BASNEF model on nurses communication skills with patients in hospitals affiliated to Tehran University of medical sciences. Iran J Health Educ Health Promot. 2019;7:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagherpour M, Abdollahzadeh H, Salamati Z. The impact of spiritual care skills instruction on nursing students’ achievement motivation and styles of communication with patient. Iran J Med Educ. 2016;16:516–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banerjee SC, Bialer PA, Levin TT, Maloney EK, et al. Communication skills training for oncology professionals. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1242–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barzapranjani S, Shariati A, Renani HA, Mousavi M. Barriers to effective communication between nurse and patient in Ahvaz Hospitals. Nurs Res. 2011;51:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rostami H, Golchin M, Mirzaei A. Evaluation of communication skills of nurse from hospitalized patients perspectine. J Urmia Nurse Midwifery Fac. 2012;10:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massoud M, Firooz N. Investigating the effect of emotional intelligence training on communication skills of students of Islamic Azad University, Najafabad Branch. Sci Res Q Psychol Methods Model. 2012;2:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemmati-Maslakpak M, Sheikhbaglu M, Baghaie R. Relationship between the communication skill of nurse-patient with patient safety in the critical care units. J Clin Nurs Midwifery. 2014;3:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur D, Sambasivan M, Kumar N. Impact of emotional intelligence and spiritual intelligence on the caring behavior of nurses: A dimension-level exploratory study among public hospitals in Malaysia. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;28:293–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bagheri F, Akbarizadeh F, Hatami H. The relationship between spiritual intelligence and happiness on the nurse staffs of the Fatemeh Zahra Hospital and Bentolhoda Institute of Boushehr City. Iran South Med J. 2011;14:256–63. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rani AA, Abidin I, Hamid M. The impact of spiritual intelligence on work performance: case studies in government hospitals of east coast of mala the macro theme review. Multidiscip J Glob Macro Trend. 2013;2:46–59. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abolfazl HS. The Relationship between Spiritual Intelligence and Communication Skills with the Effectiveness of High School Principals in Fars Province. First International Conference on Political Epic (with an Approach to Middle East Developments) and Economic Epic (with an Approach to Management and Accounting. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghasemi SS, Shami S, Olyaie N, Nematifard T, Nemati M, Khorshidi M. An investigation into the correlation between Spiritual intelligence and communication skills among nursing students. SJNMP. 2017;3:49–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emmons RA. Is spirituality an intelligence? Motivation, cognition, and the psychology of ultimate concern. Int J Psychol Relig. 2000;10:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heydari A, Meshkinyazd A, Soudmand P. The effect of spiritual intelligence training on job satisfaction of psychiatric nurses. Iran J Psychiatry. 2017;12:128–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kounenou K, Aikaterini K, Georgia K. Nurses’ communication skills: Exploring their relationship with demographic variables and job satisfaction in a Greek sample. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2011;30:22–75. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie J, Ding S, Wang C, Liu A. An evaluation of nursing students’ com munication ability during practical clinical training. Nurs Educ Today. 2013;33:823–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salimi M, Peyman H, Sadeghifar J, Rakhshan ST, Alizadeh M, Yamani N. Assessment of interpersonal communication skills and associated factors among students of Allied Medicine School in Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Iran J Med Educ. 2013;12:895–902. [Google Scholar]