ABSTRACT

Background

Emerging evidence supports the health benefits of ginger for a range of conditions and symptoms; however, there is a lack of synthesis of literature to determine which health indications are supported by quality evidence.

Objectives

In this umbrella review of systematic reviews we aimed to determine the therapeutic effects and safety of any type of ginger from the Zingiber family administered in oral form compared with any comparator or baseline measures on any health and well-being outcome in humans.

Methods

Five databases were searched from inception to April 2021. Review selection and quality were assessed in duplicate using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews–2 (AMSTAR-2) checklist and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method, with results presented in narrative form.

Results

Twenty-four systematic reviews were included with 3% overlap of primary studies. The strongest evidence was found for the antiemetic effects of ginger in pregnant women (effect size: large; GRADE: high), analgesic effects for osteoarthritis (effect size: small; GRADE: high), and glycemic control (effect size: none to very large; GRADE: very low to moderate). Ginger also had a statistically significant positive effect on blood pressure, weight management, dysmenorrhea, postoperative nausea, and chemotherapy-induced vomiting (effect size: moderate to large; GRADE: low to moderate) as well as blood lipid profile (effect size: small; GRADE: very low) and anti-inflammatory and antioxidant biomarkers (effect size: unclear; GRADE: very low to moderate). There was substantial heterogeneity and poor reporting of interventions; however, dosage of 0.5–3 g/d in capsule form administered for up to 3 mo was consistently reported as effective.

Conclusions

Dietary consumption of ginger appears safe and may exert beneficial effects on human health and well-being, with greatest confidence in antiemetic effects in pregnant women, analgesic effects in osteoarthritis, and glycemic control. Future randomized controlled and dose-dependent trials with adequate sample sizes and standardized ginger products are warranted to better inform and standardize routine clinical prescription.

Keywords: ginger, Zingiber officinale, chronic disease, pain, gastrointestinal conditions, umbrella review

Introduction

Zingiber officinale Roscoe, the most common ginger species, contains 80–90 nonvolatile compounds that have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antiemetic effects, as well as lowering blood pressure, blood lipid, and blood glucose (1–3). The myriad of mechanisms of action have been extensively examined in animal and cell models, mostly involving gingerol, shogaol, zingerone, gingerdiol, and paradol compounds (3, 4). Briefly, the anti-inflammatory effects of ginger have been linked to reducing pain and the vasodilatory effects to lowering blood pressure (3, 4). Ginger has been found to inhibit the production of cholesterol as well as adipocytes, thus benefiting the blood lipid profile and weight management, respectively (3, 4). Ginger compounds have also been shown to act similarly to hypoglycemic agents in assisting with transportation of glucose into cells (3), as well as antiemetic medications to block the activation of receptors that initiate nausea and vomiting pathways (3, 5). Furthermore, ginger consumption has been endorsed by numerous clinical practice guidelines (6–8) and was reported to be among the most common supplement used by pregnant women (9–12) and people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (13–15), hypertension (14), and those with cancer as a complementary rather than alternative medicine (16, 17).

Despite common clinical use and mechanistic studies supporting possible pathways of action to promote the use of ginger to support human health and well-being, there is a lack of quality synthesis of research to determine what health effects have the strongest evidentiary support in humans. Anh and colleagues (2) conducted a systematic review of 109 primary studies published up until 2019 that explored the human health benefits of ginger, finding beneficial effects for inflammation, metabolic syndromes, and gastrointestinal function. However, these authors did not conduct a meta-analysis, thus warranting exploration of other systematic reviews that have used meta-analysis to pool effects as well as consideration of the methodological quality of systematic reviews that have been used to guide clinical practice (2). Li and colleagues (18) conducted an umbrella review of systematic reviews examining the efficacy of ginger for any health condition and therefore did not consider the effects on healthy adults. In this article the authors discussed methodological quality of reviews and highlighted the plethora of systematic reviews on the topic with inconsistent evidence and the growing interest in this research area, but included only reviews published up until 2018. Furthermore, Li and colleagues (18) combined all modes of delivery (oral, aromatherapy, topical, and moxibustion) which have different mechanisms of action. Comprehensive synthesis of up-to-date highest-level systematic review evidence using rigorous study design and consideration of methodological quality for the effects of dietary ginger on human health would be useful to guide the integration of adjuvant use into clinical practice to address both general health and well-being as well as therapeutic uses for disease management.

Therefore, this umbrella review of systematic reviews of clinical trials aimed to determine the therapeutic effects and safety of any type of ginger from the Zingiber family administered in oral form and compared with any comparator or baseline measures on any health and well-being outcome in humans.

Methods

This umbrella methodology of this review was guided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (19) and the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis on Umbrella Reviews (20) and was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID: CRD42020197925). The study was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (21).

Search strategy

Electronic databases [PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Google Scholar] and the PROSPERO register were searched from database inception until 4 April 2021. Per the Practical Tool for Searching Grey Literature (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health) the first 120 records were taken from Google Scholar (22). The search strategy was based on the following structure: [(ginger* OR zingiber officinale*) AND (systematic review OR meta-analysis*)] and was designed in PubMed using a combination of keywords and controlled vocabulary then translated to other databases with Polyglot (23) (Supplemental Table 1). Google Scholar, Pubmed search updates, and reference lists of included reviews and relevant literature were assessed to identify additional systematic reviews not located in the search strategy up until April 2021.

Eligibility and record screening

Screening of titles and abstracts, then full text, was completed by 2 investigators independently (MC and ARD) in Endnote X9 (24). Disagreements were managed via consensus between reviewers or were resolved by discussion with a third researcher (SM).

Published peer-reviewed systematic reviews that met the following criteria were included: 1) systematic reviews, being regarded as the highest level of evidence, were defined as follows with guidance from the PRISMA Protocols Statement (21): i) had an explicit set of aims, ii) employed a reproducible methodology, including a systematic search strategy and selection of studies, and iii) had a systematic presentation and synthesis of the characteristics and findings of included studies (conducted meta-analysis and/or narrative synthesis as part of their analysis); 2) for the most comprehensive synthesis of available evidence, eligible clinical trials reviewed by the systematic reviews were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized or noncontrolled intervention trials, and observational studies; 3) examined the effects of any type of ginger from the Zingiber family administered in oral form and not in conjunction with any other therapeutic product; 4) compared ginger with placebo, other medicinal product, usual care, or no comparator; 5) (for systematic reviews that included noneligible intervention arms, e.g., turmeric, nonhuman sample) included only if the ginger group and human population were reported separately; and 6) reported on any health-related or physiological outcome in humans.

Systematic reviews were excluded if they comprised only 1 primary study that reported on the effects of ginger or if they could not be translated into English. Studies that examined the effects of ginger administered via nonoral routes (e.g., topical, aromatherapy, moxibustion) were excluded due to these formulations containing different compositions and having mechanisms of action drastically different from those of orally consumed ginger. If multiple systematic reviews existed on the same topic and included the same primary studies and outcomes, only the most recent review and/or the review for which which meta-analyses were conducted was used (Supplemental Table 2).

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Primary outcomes of interest were any health and well-being outcome relating to oral dietary or supplementary ginger consumption. Secondary outcomes were study and participant characteristics and adverse events. All data were extracted independently by a single first investigator (MC, ARD, or CI) in tabular format (Supplemental Table 3) and checked for accuracy by a second investigator (MC, ARD, or CI), with disagreements managed by consensus or involvement of a third investigator (SM). Where outcome data were missing, inadequately reported, or reported differently across systematic reviews, data were extracted directly from the primary studies if possible. Where only a proportion of included primary studies of systematic reviews met the eligibility criteria for ginger intervention or human population, outcome data from only relevant primary studies were reported.

Individual study quality assessment using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR-2) Checklist (25) was carried out independently on all studies by 2 investigators [MC and (ARD or CI)], with disagreements managed by consensus or resolved by discussion with a third investigator (SM). The AMSTAR-2 is a 16-question tool that judges each item as “yes” or “no” and yields a final overall rating for the confidence in the results of the systematic review as “high,” “moderate,” “low,” or “critically low” (25).

If the certainty in the estimated effect of each meta-analysis was not determined using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method (26) by systematic review authors; it was calculated by the current umbrella review authors using GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool software [McMaster University, 2015 (developed by Evidence Prime, Inc)]. Certainty in the evidence can be downgraded for risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias and upgraded for a large effect size, dose–response gradient, or effect of residual confounding. The GRADE approach provides 4 levels of certainty for the estimated effect: “very low” (very little confidence), “low” (limited confidence), “moderate” (moderately confident), and “high” (very confident) (26). Where GRADE level of evidence was determined by the current review authors, it was conducted by MC and revised and confirmed by SM.

Data synthesis

Data were reported via narrative synthesis, per that of the included systematic reviews, and no data reanalysis (i.e. meta-analysis) was conducted, per the Joanna Briggs Institute recommendations for umbrella reviews (20). Primary studies of included systematic reviews that were included in ≥2 systematic reviews were presented in tabular format (Supplemental Figure 1). The extent to which primary studies overlap in the included systematic reviews was calculated and reported as the percentage of primary study overlap:  whereby N represents the total number of primary studies including double counting of overlapping studies, r is the number of primary studies not including double counting of overlapping studies, and c is the total number of systematic reviews (27).

whereby N represents the total number of primary studies including double counting of overlapping studies, r is the number of primary studies not including double counting of overlapping studies, and c is the total number of systematic reviews (27).

The most recent and/or comprehensive meta-analyses for each outcome were summarized in tabular format. Whereby systematic reviews did not conduct meta-analysis to guide overall conclusions regarding statistical significance of outcomes, a modified consistency rating (28) was used: (number of primary studies that reported a statistically significant positive result/total number of studies reporting that outcome) × 100. A modified consistency rating of ≥66% was required to report an overall positive effect (28). The quality of systematic reviews assessed using AMSTAR-2 and GRADE were presented in tabular format (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5).

Results

Systematic review characteristics

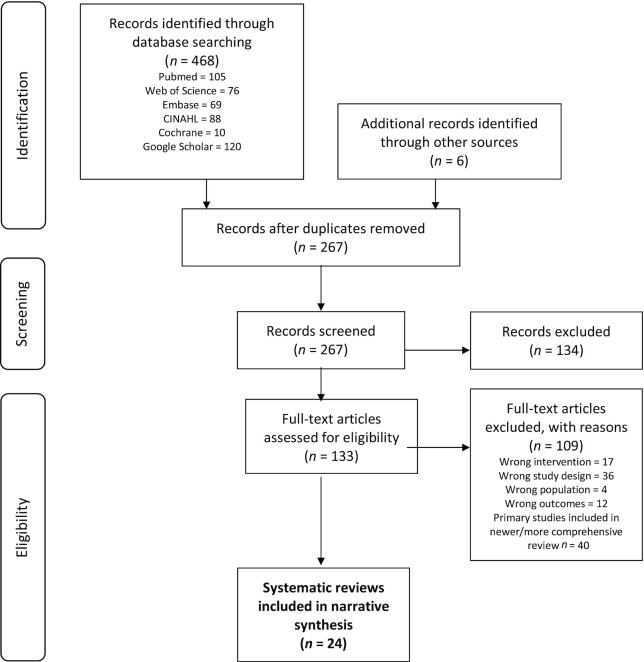

Twenty-four systematic reviews were included, which had 2–109 primary studies in each, representing 180 primary studies in total (Figure 1). Although 87 of the primary studies were included in ≥2 systematic reviews, a 3% overlap of primary studies in the included systematic reviews was calculated (Supplemental Figure 1). The main reason for exclusion at full-text review was due to all primary studies and outcomes of screened systematic reviews being included in newer and/or more comprehensive reviews (n = 40 reviews; Supplemental Table 2). Of these excluded records, 15 addressed nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, 5 addressed pain, and 5 addressed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA Flow chart for search strategy exploring the effects of ginger on human health outcomes.

The majority (79%) of systematic reviews exclusively included RCTs (2, 29–46), and 21% included a combination of the eligible study designs (Table 1; Supplemental Table 3). Seven (29%) systematic reviews only included placebo-controlled trials (30, 34, 38, 42–45) and the remaining systematic reviews mainly examined a combination of placebo, usual care, or a medicine as the comparator with ginger. Zingiber officinale was examined in the primary studies of 11 (46%) systematic reviews (30, 32, 34, 37–39, 41, 44, 45, 47, 48) and the remaining 13 (54%) reviews did not specify the species of ginger administered. Most systematic reviews explored multiple forms of ginger consumption, but ginger capsules were the most commonly administered [n = 14 (58%) systematic reviews] (2, 29, 32, 33, 36, 39–42, 45, 46, 48–50) followed by ginger powder [n = 6 (25%) of systematic reviews; Table 2] (30, 31, 34, 35, 37, 38). Dosage of ginger varied greatly between primary studies, with 0.5–2 g/d being most commonly administered (2, 29–35, 37–42, 44–47, 49, 50). Only 2 systematic reviews (2, 48) reported the active constituents of ginger formulations used (n = 19 primary studies in total); which was most commonly gingerols or a combination of gingerols and shogaols. Of the 16 (67%) systematic reviews (2, 29, 30, 32, 33, 36–38, 40–43, 45, 48–50) that reported frequency of ginger administration, dosing frequency varied between once, twice, three, or four times daily. Interventions of ≤10 d duration were most commonly used in primary studies of the 6 systematic reviews that examined the analgesic effects of ginger for dysmenorrhea or headache (2, 29, 36, 41, 42, 45). Primary studies of the 8 systematic reviews that examined the metabolic effects of ginger commonly administered ginger for longer durations of 6 wk to 3 mo (2, 30–32, 34, 35, 47, 48). Duration of intervention ranged from 1 d to 3 mo for all other outcomes and population groups.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews exploring the effects of ginger consumption on human health outcomes1

| SR Author and year (ref) | Primary studies, n (study design) | Participants, n | Ginger intervention | Comparator (n) | Outcome | Primary study quality | SR quality (AMSTAR-2) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | IGs, n | Species (n) | Form (n) | Dose, g (n) | Frequency (n) | Duration (n) | Analgesic | Metabolic | GI | Adverse | Other | ||||||

| 109 (RCT) | M/F mixed health | NR | 113 | NR | Most cap | Mostly 0.5–1.5 | SD OD to QID | 3 mo | Placebo (89) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 39% high | Low | |

| Drug/vitamin (14) | |||||||||||||||||

| Usual care (6) | |||||||||||||||||

| Ebrahimzadeh-Attari 2017 (30) | 3 (RCT) | M/F BMI ≥25 | NR | 3 | ZO | Pow | 1 (1) | SD (1) | Placebo | √ | Most low/unclear ROB | Low | |||||

| 2 (2) | NR (2) | 10–12 wk (2) | |||||||||||||||

| Balbontin 2019 (51) | 17 (NR) | F pre-/postnatal period | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | √ | High/average | Low | ||||

| Bartels 2015 (39) | 5 (RCT) | M/F OA | 874 | 5 | ZO (3), NR (2) | Cap | 0.5 (3) | NR | 3–4 wk (2) | Placebo (5) | √ | √ | Most unclear ROB | Mod | |||

| 1 (2) | 6 wk (2) | Drug/vitamin (2) | |||||||||||||||

| 12 wk (1) | |||||||||||||||||

| Chen 2020 (42) | 2 (RCT) | M/F migraine | 214 | 2 | NR | Cap | 0.4 (1) | OD (1) | SD (1) | Placebo | √ | High | Mod | ||||

| 0.6 (1) | TID (1) | 3 mo (1) | |||||||||||||||

| Crichton 2019 (49) | 18 (RCT: 15; non-RCT: 3) | M/F CTX for cancer | 1650 | 21 | NR | Cap (18) | <1 (5) | BD (11) | <5 d (3) | Placebo (14) | √ | √ | √ | Most low ROB | High | ||

| Pow (2) | 1–2 (15) | TID (1) | 5–10 d (8) | Usual care (4) | |||||||||||||

| Drink (1) | NR (1) | QID (4) | >1 mo (7) | ||||||||||||||

| NR (2) | |||||||||||||||||

| Daily 2015 (29) | 7 (RCT) | F dysmenorrhea | 651 | 9 | NR | Cap | <1 (3) | OD (2) | 3–5 d (8) | Placebo (4) | √ | √ | Most low/mod | Mod | |||

| 1–2 (6) | BD (2) | PRN (1) | Drug/vitamin (2) | ||||||||||||||

| TID (2) | Stretching (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| QID (1) | |||||||||||||||||

| Dilkothornsakul 2021 (43) | 2 (RCT) | F lactating | 133 | 2 | NR | Cap (1) | 1 (1) | BD | 3 d (1) | Placebo | √ | √ | Low/unclear ROB | Mod | |||

| Pow (1) | 10 (1) | 7 d (1) | |||||||||||||||

| Hasani 2019 (31) | 6 (RCT) | M/F metabolic conditions | 345 | 6 | NR | Pow | 0.5 (1) | NR | 7–8 wk (3) | Placebo (4) | √ | 100% high | Low | ||||

| 1.6–2 (2) | 10 wk (2) | Black tea (1) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 (3) | 12 wk (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| Hu 2020 (40) | 13 (RCT) | F prenatal | 1174 | 15 | NR | Cap (11) | <1 (1) | TID (4) | 3–4 d (11) | Placebo (8) | √ | √ | Most low/unclear ROB | Low | |||

| Syrup (1) | 1 (9) | QID (1) | 2–3 wk (2) | Drug/vitamin (7) | |||||||||||||

| Bisc (1) | 1.5–2.5 (3) | NR (8) | |||||||||||||||

| Jafarnejad 2017 (32) | 9 (RCT) | M/F T2DM or HL | 609 | 9 | ZO | Cap (6) | <1 (2) | BD (2) | 2 mo (6) | Unspecified control | √ | √ | 56% high | Low | |||

| 3 mo (3) | |||||||||||||||||

| Tab (3) | 1–2 (2) | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 (5) | |||||||||||||||||

| Jalali 2020 (46) | 20 (RCT) | M/F mixed health | 888 | 20 | NR | Cap (14) | <1 (4) | NR | 10–11 d (2) | Unspecified control | √ | 80% high | Low | ||||

| Tab (2) | 1–2 (12) | 4–8 wk (6) | |||||||||||||||

| Pow (2) | >2–3 (4) | 10–12 wk (12) | |||||||||||||||

| Raw (2) | |||||||||||||||||

| Khorasani 2020 (33) | 18 (RCT) | F prenatal period | 1690 | 18 | NR | Cap (12) | <1 (5) | BD (1) | 3–7 d (13) | Placebo (11) | √ | NR | Low | ||||

| Bisc (1) | 1 (9) | TID (4) | 14–21 d (3) | Drug/vitamin (7) | |||||||||||||

| Liquid (2) | >1–2.5 (3) | QID (1) | 60 d (1) | Usual care (1) | |||||||||||||

| NR (3) | NR (1) | NR (12) | |||||||||||||||

| Macit 2019 (47) | 8 (RCT: 6; Pro: 2) | M/F healthy or BMI ≥30 | 285 | 8 | ZO | Pow (2) | 0.03–0.04 (2) | NR | SD (3) | Placebo (4) | √ | NR | Crit low | ||||

| NR (6) | 1 (2) | 4 wk (2) | Unspecified control (2) | ||||||||||||||

| 2 (3) | 10–12 wk (3) | None (2) | |||||||||||||||

| 20 (1) | |||||||||||||||||

| Maharlouei 2019 (34) | 13 (RCT) | M/F BMI ≥25 | 473 | 13 | ZO | Pow (12) | 0.05 (1) | NR | 2 wk (1) | Placebo | √ | Most low ROB | Low | ||||

| Ext (1) | 1–2 (8) | 6–8 wk (4) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 (4) | 10–12 wk (9) | ||||||||||||||||

| Marx 2015 (48) | 10 (RCT: 8; Obs: 2) | M/F mixed health | 650 | 10 | ZO | Cap (6) | 1–2 (2) | OD (5) | 1 (2) | Placebo (5) | √ | √ | Most low ROB | Mod | |||

| Raw/cook (2) | 3–4 (2) | BD (1) | 1–2 wk (5) | NR (5) | |||||||||||||

| NR (2) | 5–5 (4) | TID (1) | 3 mo (1) | ||||||||||||||

| NR (2) | NR (3) | NR (2) | |||||||||||||||

| Mazidi 2016 (35) | 9 (RCT) | M/F metabolic conditions | 449 | 9 | NR | Pow (4) | 1 (3) | NR | 7–10 wk (4) | Placebo | √ | √ | √ | 100% low ROB | Mod | ||

| NR (5) | >1–2 (3) | 2–3 mo (4) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 (3) | NR (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| Morvaridzadeh 2020 (44) | 16 (RCT) | M/F mixed health | 1010 | 16 | ZO | NR | 1–1.9 (4) | NR | 4–6 wk (3) | Placebo | √ | √ | Most low/unclear ROB | Low | |||

| 2 (5) | 8–10 wk (8) | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 (5) | 12 wk (3) | ||||||||||||||||

| NR (1) | |||||||||||||||||

| Negi 2021 (45) | 8 (RCT) | F dysmenorrhea | 1066 | 8 | ZO (1) | Cap | <1 (4) | BD (1) | 2–3 d (5) | Placebo (5) | √ | √ | Most low/unclear ROB | Crit low | |||

| NR (7) | 1 (3) | TID (3) | 4–5 d (2) | Drug/vitamin (3) | |||||||||||||

| 1.5 (1) | QID (4) | NR (1) | |||||||||||||||

| Ozgoli 2018 (50) | 10 (RCT: 2; non-RCT 8) | F prenatal period | 1059 | 11 | NR | Cap (8) | 0.25–1.5 (8) | BD (2) | 4 d (10) | Placebo (7) | √ | √ | Most high | Crit Low | |||

| Bisc (1) | 2–8g2 (2) | QID (3) | 1 wk (1) | NR (4) | |||||||||||||

| Syrup (2) | NR (1) | NR (6) | |||||||||||||||

| Pattanittum 2016 (41) | 4 (RCT) | F dysmenorrhea | 416 | 4 | ZO | Cap | 0.5–0.75 (3) | TID (1) | 3 d (1) | Placebo (4) | √ | √ | Most low/unclear ROB | Mod | |||

| 1.5 (1) | NR (1) | 5 d (1) | Drug/vitamin (1) | ||||||||||||||

| Rajabzadeh 2018 (36) | 2 (RCT) | F dysmenorrhea | 220 | 2 | NR | Cap | 0.5–1 | BD (1) | 3 d (1) | Placebo (1) | √ | √ | Mod/high | Low | |||

| QID (1) | 10 d (1) | Drug/vitamin (1) | |||||||||||||||

| Toth 2018 (37) | 10 (RCT) | F postop | 918 | 12 | ZO | Pow (10) | <1 (4) | SD (11) | 1 d | Placebo (10) | √ | √ | Most unclear ROB | Mod | |||

| Raw (1) | 1 (6) | Pre-& postsurgery (1) | Unspecified control (2) | ||||||||||||||

| Ext (1) | 1.5–2 (2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Wilson 2015 (38) | 8 (RCT) | M/F mixed health | 246 | 8 | ZO | 1–2 (6) | 1 d (2) | ||||||||||

| 3–4 (2) | SD (2) | 5–11 d (3) | |||||||||||||||

| NR | 6–10 wk (3) | Placebo | |||||||||||||||

AMSTAR-2, Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews 2; Crit, critically; CTX, chemotherapy; GRADE, Grading Recommendations, Assessment;, HL, hyperlipidemia; IG, intervention group; mod, moderate; NA, not assessed; non-RCT, non–randomized controlled trial; NR, not reported; OA, osteoarthritis; Obs, observational study; PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; PRN, as needed (until pain relief); Pro, prospective study; RCT, randomized controlled trial; ROB, risk of bias; SD, single dose; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; ZO, Zingiber officinale.

1–4 tsp = 2–8g.

TABLE 2.

Synthesis of primary studies evaluating the effect of ginger on each human outcome as reported in the included systematic reviews1

| Primary studies | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | Participant type | Total sample size, n | Ginger form | Duration | Daily ginger dose, g | Positive effect (P < 0.05) (modified consistency rating) | Overlap | Outcome meta-analyzed | |

| Analgesic effects | |||||||||

| Dysmenorrhea | |||||||||

| Pain severity (2, 29, 36, 41, 45) | 7 | Dysmenorrhea | 835 | Cap | 3–10 d | 0.5–1.5 | 7 (100%) | 21% | Yes |

| Pain duration (29, 45) | 2 | Dysmenorrhea | 245 | Cap | 3–5 d | 1–1.5 | 0 (0%) | 33% | Yes |

| Osteoarthritis | |||||||||

| Pain severity (2, 39) | 7 | Knee/hip OA | 1072 | Cap/pow/tab | 3–12 wk | 0.2–1.5 | 4 (57%) | 43% | Yes |

| Knee stiffness severity (39) | 2 | Knee OA | 451 | Cap | 6 wk | 0.5 | 2 (100%) | NA | No |

| Pain-related disability (39) | 4 | Knee OA | 704 | Cap | 3–12 wk | 0.5–1 | 3 (75%) | NA | Yes |

| Postexercise muscle pain | |||||||||

| Pain severity (2, 38) | 6 | Trained/untrained | 223 | Pow | SD, 6 wk | 2–4 | 3 (50%) | 43% | No |

| Headache/migraine | |||||||||

| Severity (2, 42) | 4 | Migraine/post op | 427 | Cap | SD, 3 mo | 0.4–0.8 | 4 (100%) | 25% | No |

| Treatment response (42) | 2 | Migraine | 167 | Cap | SD, 3 mo | 0.4–0.6 | 0 (0%) | NA | Yes |

| Metabolic Effects | |||||||||

| BP | |||||||||

| Systolic (2, 31) | 6 | T2DM/BMI ≥25/HL | 345 | Pow | 7–12 wk | 0.5–9 | 6 (100%) | 17% | Yes |

| Diastolic (2, 31) | 6 | T2DM/BMI ≥25/HL | 345 | Pow | 7–12 wk | 0.5–9 | 6 (100%) | 17% | Yes |

| Blood lipids | |||||||||

| Triglycerides (2, 32, 34, 35) | 14 | T2DM/BMI ≥25/PD/HL | 720 | Cap/pow/tab/ext | SD, 3 mo | 0.005–9 | 10 (71%) | 21% | Yes |

| HDL-C (2, 32, 34, 35) | 14 | T2DM/BMI ≥25/PD/HL | 712 | Cap/pow/tab/ext | SD, 3 mo | 0.005–9 | 7 (50%) | 19% | Yes |

| LDL-C (2, 32, 34, 35) | 14 | T2DM/BMI ≥25/PD/HL | 771 | Cap/pow/tab/ext | SD, 3 mo | 0.005–9 | 10 (71%) | 10% | Yes |

| TC (2, 32, 34) | 16 | T2DM/BMI ≥25/PD/HL | 842 | Cap/pow/tab/ext | SD, 3 mo | 0.005–9 | 10 (63%) | 13% | Yes |

| Blood clotting | |||||||||

| Platelet aggregation (2, 48) | 6 | Healthy/HTN/MI | 128 | Cap | SD, 4 mo | 1–10 | 2 (33%) | 17% | No |

| Throm B2 production (2, 48) | 3 | Healthy/obese | 99 | Cap/raw/cook | 1–6 wk | 5–40 | 1 (33%) | 33% | No |

| Fibrinogen (2, 48) | 3 | Obese/MI | 102 | Cap | SD, 4 mo | 3–10 | 0 (0%) | 33% | No |

| Fibrinolytic activity (2, 48) | 3 | Obese/MI | 102 | Cap | SD, 4 mo | 3–10 | 0 (0%) | 33% | No |

| Glycemic control | |||||||||

| Fasting BGL (2, 32, 34, 35) | 21 | T2DM/PD/HL/BMI ≥25 | 917 | Cap/tab | SD, 3 mo | 0.05–4 | 11 (52%) | 19% | Yes |

| HbA1c (2, 35) | 4 | T2DM/BMI ≥25 | 222 | Cap/tab | SD, 3 mo | 0.05–4 | 4 (100%) | 75% | Yes |

| Blood insulin (2, 3, 30, 34) | 11 | T2DM/BMI ≥25 | 474 | Cap/tab | SD, 3 mo | 0.05–4 | 9 (82%) | 9% | Yes |

| Insulin resistance2 (2, 30, 34) | 10 | T2DM/BMI ≥25 | 409 | Cap/tab | SD, 3 mo | 0.05–4 | 9 (90%) | 15% | Yes |

| Weight management | |||||||||

| Body weight (2, 30, 34, 47) | 6 | Healthy/BMI ≥25 | 223 | Pow/ext | 1 d, 3 mo | 0.05–20 | 2 (33%) | 33% | Yes |

| BMI (2, 3, 30, 34, 47) | 6 | Healthy/BMI ≥25 | 223 | Pow/ext | 1 d, 3 mo | 0.05–20 | 2 (33%) | 33% | Yes |

| Waist-to-hip ratio (2, 34) | 5 | Healthy/T2DM/BMI ≥25 | 169 | Pow/ext | 1 d, 3 mo | 0.05–20 | 2 (40%) | 0% | Yes |

| Hip circu ference (2, 34) | 3 | T2DM/BMI ≥25 | 162 | Pow | 8–12 wk | 0.5–2 | 1 (33%) | 0% | Yes |

| Appetite (2, 30, 47) | 4 | Healthy/BMI ≥25/PD | 170 | Pow/tab/cook | SD, 6 wk | 2–20 | 3 (75%) | 50% | No |

| Fullness (2, 30) | 2 | Healthy/BMI ≥25/PD | 56 | Pow/tab/cook | SD, 6 wk | 1–20 | 2 (100%) | 0% | No |

| Food intake (2, 30) | 3 | Healthy/BMI ≥25/PD | 100 | Pow/tab/cook | SD, 6 wk | 1–20 | 2 (67%) | 0% | No |

| Energy intake (30, 47) | 3 | Healthy/BMI ≥25/PD | 102 | Pow/tab/cook | SD, 6 wk | 1–20 | 3 (100%) | 50% | No |

| Thermogenesis (30, 47) | 3 | Healthy/BMI ≥25/PD | 79 | Pow/tab/cook | SD, 6 wk | 1–20 | 3 (100%) | 0% | No |

| Gastrointestinal Effects | |||||||||

| Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy | |||||||||

| Nausea incidence (2, 33, 40, 50) | 16 | Pregnant | 1513 | Cap/syrp/bisc/ext | SD, 21d | 0.5–2.5 | 15 (94%) | 59% | Yes |

| Nausea severity (2, 33, 40) | 15 | Pregnant | 1563 | Cap/syrp/bisc/ext | SD, 21d | 0.5–2.5 | 15 (100%) | 63% | Yes |

| Vomiting incidence (2, 33, 40) | 16 | Pregnant | 1702 | Cap/syrp/bisc/ext | SD, 21d | 0.5–2.5 | 14 (88%) | 47% | Yes |

| Retching incidence (2, 33) | 3 | Pregnant | 531 | Cap/ext | 4–21 d | 0.1–0.8 | 3 (100%) | 50% | No |

| PONV | |||||||||

| PONV incidence (2, 37) | 14 | Mixed postop | 1290 | Pow/raw/ext | SD | 0.1–2 | 8 (57%) | 36% | No |

| Nausea incidence (37) | 9 | Mixed postop | 858 | Pow/raw/ext | SD | 0.1–2 | 6 (67%) | NA | Yes |

| Nausea severity (2, 37) | 10 | Mixed postop | 1129 | Pow/raw/ext | SD | 0.1–2 | 9 (90%) | 20% | Yes |

| Vomiting incidence (37) | 7 | Mixed postop | 918 | Pow/raw/ext | SD | 0.1–2 | 4 (57%) | NA | Yes |

| Antiemetics demand (2, 37) | 6 | Mixed postop | 738 | Pow/ext | SD | 0.1–1 | 4 (67%) | 33% | Yes |

| CINV | |||||||||

| Anticip CIN incidence (2, 49) | 2 | CTX for cancer | 302 | Cap | 5–6 d | 1.2–2 | 2 (100%) | 100% | No |

| Overall CIN incidence (2, 49, 52) | 10 | CTX for cancer | 1172 | Cap/tab/pow | 3 d, 6 c | 0.02–2 | 2 (20%) | 35% | Yes |

| Acute CIN incidence (2, 49, 52) | 7 | CTX for cancer | 1236 | Cap/tab/pow | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–2 | 3 (43%) | 43% | Yes |

| Delayed CIN incidence (2, 49, 52) | 8 | CTX for cancer | 1261 | Cap/tab/pow | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–2 | 2 (25%) | 38% | Yes |

| Overall CIN severity (2, 49, 52) | 10 | CTX for cancer | 1182 | Cap/tab/pow | 3–5 d | 0.5–2 | 4 (40%) | 55% | Yes |

| Acute CIN severity (2, 49) | 8 | CTX for cancer | 565 | Cap/tab/pow | 3–5 d | 0.5–2 | 1 (13%) | 88% | Yes |

| Delayed CIN severity (2, 49) | 8 | CTX for cancer | 665 | Cap/tab/pow | 3–5 d | 0.5–2 | 5 (63%) | 88% | Yes |

| Overall CIV incidence (2, 49, 52) | 11 | CTX for cancer | 953 | Cap/tab/pow | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–2 | 3 (27%) | 50% | Yes |

| Anticip CIV incidence (2, 49, 52) | 3 | CTX for cancer | 183 | Cap | 5–6 d | 1.2–2 | 2 (67%) | 33% | No |

| Acute CIV incidence (2, 49, 52) | 10 | CTX for cancer | 965 | Cap/tab/pow | 5 d, 3 c | 0.02–1 | 3 (30%) | 45% | Yes |

| Delayed CIV incidence (2, 49, 52) | 10 | CTX for cancer | 965 | Cap/tab/pow | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–2 | 4 (40%) | 45% | Yes |

| CIV frequency (2, 49, 52) | 3 | CTX for cancer | 271 | Cap | 5 d | 0.5 | 2 (67%) | 17% | No |

| CINV–related QoL (2, 49) | 4 | CTX for cancer | 660 | Cap/tab/pow | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–1.5 | 3 (60%) | 100% | Yes |

| CINV-related fatigue (2, 49) | 5 | CTX for cancer | 652 | Cap/tab/pow | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–2 | 3 (75%) | 100% | Yes |

| Motion Sickness | |||||||||

| N&V incidence (2) | 3 | Healthy | 149 | Cap | SD | 1–2 | 2 (75%) | NA | No |

| Nausea incidence (2) | 2 | Healthy | 113 | Cap/pow | SD | 1–2 | 1 (50%) | NA | No |

| Vertigo incidence (2) | 2 | Healthy | 87 | Cap | SD | 1 | 1 (50%) | NA | No |

| Nystagmus (2) | 2 | Healthy | 150 | Cap | SD | 1 | 1 (50%) | NA | No |

| Gastric motility | |||||||||

| Gastric emptying (2) | 5 | Healthy/resp/dyspnoea | 144 | Cap/EN | 1–21 d | 0.4–1.2 | 3 (60%) | NA | No |

| Gastric dysrhythmia (2) | 3 | Induced dysrhythmia | 137 | Cap | 1 d | 1–2 | 2 (75%) | NA | No |

| Anti-inflammatory effects | |||||||||

| CRP (2, 35, 44, 46) | 15 | T2DM/BMI ≥30/KD/Ca/ NAFLD/OA/TB | 689 | Cap/pow/tab/raw | 4–12 wk | 0.5–3 | 12 (80%) | 38% | Yes |

| TNF-α (2, 38, 44, 46) | 9 | T2DM/NAFLD/OA/TB/resp | 478 | Cap/pow/ext | 4–12 wk | 1.5–3 | 7 (78%) | 37% | Yes |

| IL-6 (2, 38, 44, 46) | 7 | T2DM/BMI ≥30/PD/Ca/resp | 248 | Cap/pow | 6–10 wk | 1–3 | 6 (86%) | 14% | Yes |

| IL-1 (2, 38) | 3 | Healthy/OA/resp | 160 | Cap/pow/EN | 3–8 wk | 0.4–2 | 3 (100%) | 0% | No |

| sICAM (44) | 3 | T2DM/KD | 161 | Unspecified | 8–10 wk | 1–3 | 1 (33%) | NA | Yes |

| PGE2 (2, 38, 46) | 3 | Healthy/T2DM | 117 | Cap/raw/cook | 2–12 wk | 1.6–2 | 3 (100%) | 33% | Yes |

| Antioxidant effects | |||||||||

| MDA (2, 46) | 6 | T2DM/BMI ≥30/KD/UC | 379 | Cap/tab | 10–12 wk | 1–3 | 4 (67%) | 38% | Yes |

| TAC (2, 46) | 4 | T2DM/BMI ≥30 | 193 | Cap/tab | 10–12 wk | 1–3 | 4 (100%) | 25% | Yes |

| Effects on physical performance | |||||||||

| Range of motion (38) | 3 | Untrained | 80 | Pow | 1–11 d | 2–4 | 0 (0%) | NA | No |

| Arm circumference (38) | 3 | Untrained | 80 | Pow | 1–11 d | 2–4 | 0 (0%) | NA | No |

| Perceived exertion (38) | 2 | Untrained | 52 | Pow | 1–7 d | 2 | 0 (0%) | NA | No |

| Effects on lactation | |||||||||

| Breast milk volume (2, 43) | 2 | Postpartum | 133 | Cap | 3–7 d | 1–10 | 1 (50%) | 33% | No |

Anticip, anticipatory; BG, blood glucose concentration; Bisc, biscuit; BP, blood pressure; c, chemotherapy cycles; C, cholesterol; cap, capsules; CIN, chemotherapy-induced nausea; CINV, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; CIV, chemotherapy-induced vomiting; cook, cooked; CRP, c-reactive protein; CTX, chemotherapy; EN, enteral nutrition; ext, extract; HL, hyperlipidemia; HTN, hypertension; KD, kidney disease; MDA, malondialdehyde; MI, myocardial infarction; N, number; NA, not applicable; N&V, nausea and vomiting; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NVP, nausea and vomiting of pregnancy; OA, osteoarthritis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PGE2, Prostaglandin E2; PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; pow, powder; QID, four times daily; QoL, quality of life; resp, respiratory syndrome; SD, single dose; sICAM, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; tab, tablets; TAC, total antioxidant capacity; TB, tuberculosis; TC, total cholesterol; Throm, thromboxane; UC, ulcerative colitis.

As measured by HOMA-IR or quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI).

Systematic review study quality

Of the 24 included systematic reviews, 17% were rated as having critically low quality (38, 45, 47, 50), 46% as low quality (2, 30–34, 36, 40, 43, 44, 46, 51), 33% as moderate quality (29, 35, 37, 39, 41, 42, 48), and 4% as high quality (49) (Table 3; Supplemental Table 4). Only a single systematic review (49) reported sources of funding of primary studies (item 10) and only 2 reviews (37, 41) provided a list of excluded studies with explanations for exclusion (item 7). Most (88%) of the reviews did not provide an explanation for primary study design inclusion (item 3), 67% did not specify whether review methods were established prior to conducting the review (item 2), and 46% did not justify publication restrictions (item 4). Of the 15 reviews that conducted meta-analysis, 40% did not explore the potential impact of risk of bias in primary studies on the results of the meta-analysis (item 12). Nineteen (79%) systematic reviews reported overall conclusions regarding primary study quality and despite different assessment tools used, the majority of reviews (95%) included primary studies that were mostly high quality or had low risk of bias (29–32, 34–36, 40–46, 48–51).

TABLE 3.

Summary of meta-analyses evaluating the effect of ginger on each human outcome as reported in the included systematic reviews1

| Findings | Intervention characteristics | Study characteristics, n | GRADE | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | MD | SMD | OR | RR | 95% CI | P value | I 2 % | Ginger form | Comparator | Duration | Ginger dose | Ginger frequency | RCT (Intervention) | Participant | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other | Overall evidence quality |

| Analgesic effects | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dysmenorrhea | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pain severity (45) | −2.7cm2 | — | — | — | −3.5, −1.8 | <0.001 | 86 | Cap | Plac | 3–5 d | 0.5–1.5 | BD, TID | 4 (4) | 368 | − | ++ | − | + | Large ES | low |

| — | — | — | 1.15 | 0.5, 2.5 | 0.72 | 77 | Cap | NSAID | 3 d | 1.0 | QID | 2 (2) | 220 | − | ++ | − | + | None | low | |

| Pain duration (45) | −2.2 h | — | — | — | −7.6, 3.2 | 0.42 | 56 | Cap | Plac | 3–5 d | 1.0–1.5 | TID, QID | 2 (2) | 245 | − | + | − | ++ | None | v low |

| Osteoarthritis | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pain severity (39) | — | −0.3 | — | — | −0.5, −0.1 | <0.001 | 27 | Cap | Plac | 3–12 wk | 0.5–1.0 | NR | 5 (5) | 874 | − | − | − | − | None | high |

| Disability (39) | — | −0.2 | — | — | −0.4, −0.0 | 0.01 | 0 | Cap | Plac | 3–12 wk | 0.5–1.0 | NR | 4 (4) | 704 | − | − | − | − | None | high |

| Headache/migraine | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Treatment response (42) | — | — | — | 2.0 | 0.4, 11.9 | 0.43 | 64 | Cap | Plac | 3 mo | 0.4–0.6 | TID | 2 (2) | 167 | − | + | − | ++ | None | v low |

| Metabolic effects | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Blood Pressure | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Systolic (31) | −6.4 mmHg2 | — | — | — | −11.3, −1.5 | <0.001 | 90 | Pow | Plac/con | 7–12 wk | 0.5–3.0 | NR | 6 (6) | 345 | − | + | − | + | large ES | low |

| Diastolic (31) | −2.1 mmHg | — | — | — | −3.9, −0.3 | <0.001 | 74 | Pow | Plac/con | 7–12 wk | 0.5–3.0 | NR | 6 (6) | 345 | − | + | − | + | None | low |

| Blood lipids | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Triglycerides (32) | −8.8 mg/dL | — | — | — | −12.0, −5.7 | <0.001 | 94 | Cap/tab | Plac/con | 2–3 mo | 0.005–3.0 | NR | 6 (7) | 428 | + | ++ | − | + | None | v low |

| HDL-C (32) | 2.9 mg/dL | — | — | — | 0.9, 4.9 | <0.001 | 98 | Cap/tab | Plac/con | 2–3 mo | 0.005–3.0 | NR | 7 (8) | 509 | + | ++ | − | ++ | None | v low |

| LDL-C (32) | −5.1 mg/dL | — | — | — | −10.5, −0.3 | 0.06 | 95 | Cap/tab | Plac/con | 2–3 mo | 0.005–3.0 | NR | 6 (6) | 433 | + | ++ | − | ++ | None | v low |

| TC (32) | −4.4 mg/dL | — | — | — | −8.7, −0.1 | <0.001 | 96 | Cap/tab | Plac/con | 2–3 mo | 0.005–3.0 | NR | 7 (8) | 509 | + | ++ | − | ++ | None | v low |

| Glycemic control | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Fasting BG (32) | −15.0 mg/dL2 | — | — | — | −19.8, −10.0 | <0.001 | 83 | Cap/tab | Con | 2–3 mo | 0.5–3.0 | NR | 7 (7) | 474 | − | ++ | − | + | large ES | low |

| HbA1c (35) | −1.01%2 | — | — | — | −2.0, −0.6 | <0.05 | 12 | Pow | Plac | 2–3 mo | 2.0–3.0 | NR | 3 (3) | 172 | − | − | − | ++ | large ES | mod |

| Blood insulinconcentrations (34) | — | −0.5 | — | — | −1.4, 0.4 | 0.23 | 86 | Pow | Plac | 2–3 mo | 0.05–2.0 | NR | 5 (5) | 178 | − | ++ | − | ++ | None | v low |

| Insulin resistance3 (34) | — | −1.72 | — | — | −2.9, −0.5 | <0.001 | 86 | Pow | Plac | 2–3 mo | 0.05–2.0 | NR | 5 (5) | 178 | − | ++ | − | + | very large ES | mod |

| Body weight management | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Body weight (34) | — | −0.72 | — | — | −1.3, −0.0 | 0.04 | 77 | Pow | Plac | 2–3 mo | 0.05–2.0 | NR | 4 (4) | 162 | − | ++ | − | + | large ES | low |

| BMI (34) | — | −0.72 | — | — | −1.4, 0.1 | <0.001 | 77 | Pow | Plac | 2–3 mo | 0.05–2.0 | NR | 4 (4) | 162 | − | ++ | − | + | large ES | low |

| Waist-to-hip ratio (34) | — | −0.5 | — | — | −0.8, −0.2 | <0.001 | 0 | Pow | Plac | 2–3 mo | 0.05–2.0 | NR | 4 (4) | 162 | − | − | − | + | None | mod |

| Hip circumference (34) | — | −0.4 | — | — | −0.8, −0.1 | 0.01 | 0 | Pow | Plac | 2–3 mo | 0.05–2.0 | NR | 3 (3) | 137 | − | − | − | + | None | mod |

| Gastrointestinal effects | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nausea incidence (40) | — | — | 7.5 | — | 4.1, 13.5 | <0.001 | 30 | Cap/other4 | Plac | 4–21 d | 1.0–2.5 | NR | 5 (5) | 261 | − | − | − | + | very large ES | high |

| Nausea severity (40) | — | 0.82 | — | — | 0.6, 1.1 | <0.001 | 39 | Cap/other4 | Plac | 4 d | 1.0–2.5 | NR | 5 (5) | 452 | − | − | − | − | very large ES | high |

| Vomiting incidence (40) | — | 0.6 | — | — | −0.3, 1.4 | 0.188 | 91 | Cap/other4 | Plac | 4 d | 1.0–2.5 | NR | 5 (5) | 452 | − | ++ | − | + | None | low |

| Postop nausea and vomiting | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nausea incidence (37) | — | — | — | −0.2 | −0.4, 0.1 | 0.137 | 56 | Pow/other4 | Plac/con | SD | 0.1–2.0 | OD | 9 (11) | 858 | + | + | − | − | None | low |

| Nausea severity (37) | — | −0.5 | — | — | −0.5, −0.0 | 0.019 | 0 | Pow | Plac/con | SD | 1.0 | OD | 3 (3) | 360 | + | − | − | + | None | low |

| Vomiting incidence (37) | — | — | — | −0.2 | −0.5, 0.1 | 0.203 | 37 | Pow/other4 | Plac/con | SD | 0.1–2.0 | OD | 7 (9) | 918 | + | − | − | − | None | mod |

| Antiemetic demand (37) | — | — | — | −0.3 | −0.6, 0.0 | 0.072 | 20 | Pow/other4 | Plac/con | SD | 0.1–1.0 | OD | 5 (7) | 563 | + | − | − | − | None | mod |

| Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Overall CIN incidence (49) | — | — | 0.8 | — | 0.6, 1.3 | 0.42 | 48 | Cap/tab | Plac | 3 d, 6c | 0.02–2.0 | BD, TID | 8 (9) | 928 | − | + | − | − | None | mod |

| Acute CIN incidence (49) | — | — | 0.8 | — | 0.5, 1.4 | 0.47 | 63 | Cap | Plac | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–2.0 | BD, TID | 5 (6) | 590 | + | + | − | − | None | v low5 |

| Delayed CIN incidence (49) | — | — | 0.9 | — | 0.7, 1.3 | 0.64 | 28 | Cap | Plac | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–2.0 | BD, TID | 6 (7) | 834 | − | − | − | + | None | mod5 |

| Overall CIN severity (49) | — | −0.1 | — | — | −0.6, 0.4 | 0.71 | 83 | Cap/pow | Plac/uc | 3–5 d | 1.0 | BD, TID | 4 (5) | 438 | − | ++ | − | − | None | low5 |

| Acute CIN severity (49) | — | −0.0 | — | — | −0.2, 0.2 | 0.76 | 0 | Cap/pow | Plac/uc | 3-5 d | 1.0 | BD, TID | 4 (5) | 438 | − | − | − | + | None | mod |

| Delayed CIN severity (49) | — | 0.0 | — | — | −0.6, 0.7 | 0.94 | 91 | Cap/pow | Plac/uc | 3-5 d | 1.0 | BD, TID | 4 (5) | 438 | − | ++ | − | + | None | v low5 |

| Overall CIV incidence (49) | — | — | 0.8 | — | 0.4, 1.4 | 0.27 | 66 | Cap | Plac | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–2.0 | BD,TID,QID | 8 (9) | 825 | − | + | − | − | None | mod |

| Acute CIV incidence (49) | — | — | 0.4 | — | 0.2, 0.8 | 0.01 | 20 | Cap | Plac | 5 d, 3 c | 0.02–1.0 | BD, TID | 3 (3) | 301 | − | − | − | − | None | mod |

| Delayed CIV incidence (49) | — | — | 0.8 | — | 0.4, 1.8 | 0.63 | 76 | Cap | Plac | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–2.0 | BD,TID,QID | 6 (7) | 671 | − | ++ | − | − | None | low |

| CINV-related QoL (49) | — | 0.5 | — | — | −0.1, 1.0 | 0.09 | 78 | Cap | Plac | 3 d, 3 c | 0.02–1.2 | BD, TID | 3 (3) | 279 | − | ++ | − | + | None | v low |

| CINV-related fatigue (49) | — | 0.2 | — | — | 0.0, 0.9 | 0.03 | 0 | Cap | Plac | 3 d | 1.0–2.0 | NR | 2 (2) | 219 | − | − | − | + | None | mod |

| Anti-inflammatory effects | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CRP (46) | −1.06 | — | — | — | −1.5, −0.5 | <0.001 | 86 | Cap/tab/pow | Con | 4-12 wk | 0.5–3.0 | NR | 10 (12) | 565 | − | ++ | − | − | None | low |

| TNF-α (44) | −0.96 | — | — | — | −1.5, −0.2 | <0.05 | 89 | NR | Plac | 4-12 wk | 1.5–2.0 | NR | 7 (7) | 428 | − | ++ | − | − | None | low |

| IL-6 (44) | −0.56 | — | — | — | −1.3, 0.4 | >0.05 | 89 | NR | Plac | 6–10 wk | 1.0–3.0 | NR | 5 (5) | 302 | − | ++ | − | − | None | low |

| sICAM (44) | 0.56 | — | — | — | −0.4, 0.3 | <0.05 | 0 | NR | Plac | 8–10 wk | 1.0–3.0 | NR | 3 (3) | 161 | − | − | − | + | None | mod |

| PGE2 (46) | −0.36 | — | — | — | −0.6, 0.0 | 0.05 | 0 | Cap/other5 | Con | 2–12 wk | 1.6–2.0 | NR | 3 (4) | 117 | − | − | − | + | None | mod |

| Antioxidant effects | ||||||||||||||||||||

| MDA (46) | −0.76 | — | — | — | −1.3, −0.0 | 0.04 | 83 | Cap/tab | Con | 10–12 wk | 1.0–3.0 | NR | 6 (7) | 270 | − | ++ | − | + | None | v low |

| TAC (46) | 1.06 | — | — | — | 0.7, 1.3 | <0.01 | 95 | Cap/tab | Con | 10–12 wk | 1.0–3.0 | NR | 4 (5) | 193 | − | ++ | − | + | None | v low |

BD, twice daily; C, cholesterol; cap, capsules; c, chemotherapy cycles; CIN, chemotherapy-induced nausea; CIV, chemotherapy-induced vomiting; cm, centimeters on 10-cm visual analogue scale (VAS); con, control; CRP, c-reactive protein; ES, effect size; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations; I2, heterogeneity; Int, intervention; MD, mean difference; MDA, malondialdehyde; NR, not reported; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OD, once daily; PGE2, Prostaglandin E2; plac, placebo; pow, powder; QID, 4 times daily; QoL, quality of life; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, single dose; sICAM, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule; SMD, standardized mean difference; st, standard care; T response, treatment response; tab, tablets; TAC, total antioxidant capacity; TC, total cholesterol: TID, 3 times daily; uc, usual care; −, not serious; +, serious; ++, very serious.

Large effect size.

As measured by HOMA-IR or quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI).

Other forms of ginger administration included raw, cooked, syrup, extract, and biscuits.

GRADE level reported as calculated in systematic review.

Unit of measure not reported; effect size not interpretable.

The GRADE certainty in the evidence for most (59%) of the 44 outcomes that were meta-analyzed in included systematic reviews was found to be very low to low, meaning there is very little to little confidence that the estimated effect represents the true value of effect (Table 3; Supplemental Table 5). There was moderate to high confidence in the effect of the remaining 41% of outcomes. GRADE ratings were mostly downgraded due to inconsistency (high heterogeneity) and imprecision (small sample sizes and wide 95% CIs) and were not improved by a large effect size in most cases. Almost all outcomes had low risk of bias in primary RCTs and no outcomes were downgraded due to indirectness or publication bias (26). However, publication bias was not able to be fully investigated due to the small number of studies included for most outcomes and, therefore, could have unknown effects on the conclusions of this review.

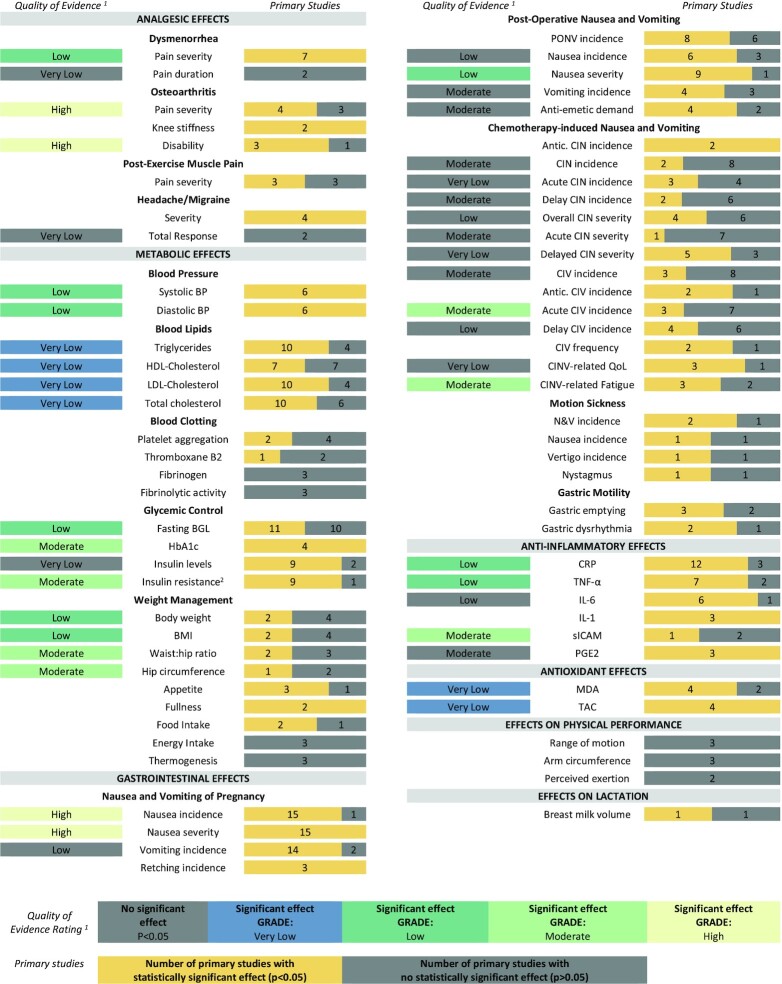

Therapeutic efficacy of ginger

Table 2 presents primary studies and Table 3 contains meta-analyses evaluating the effect of ginger on each human outcome as reported in the included systematic reviews. These results are more simply presented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of the strength of evidence for the therapeutic effects of oral ginger supplementation. The left column indicates the meta-analyses with GRADE ratings that were very low, low, moderate, or high. Numbers in the right column indicate the modified consistency rating (number of primary studies with a statistically significantly positive effect or no statistically significant effect for each outcome). 1GRADE level of evidence for meta-analysis if conducted by systematic reviews. 2As measured by HOMA-IR or QUICKI. Antic., anticipatory; BGL, blood glucose level; BP, blood pressure; CIN, chemotherapy-induced nausea; CINV, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; CIV, chemotherapy-induced vomiting; CRP, c-reactive protein; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations; MDA, malondialdehyde; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; QoL, quality of life; QUICKI, quantitative insulin sensitivity check; sICAM, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule; TAC, total antioxidant capacity.

Analgesic effects

Eight systematic reviews (2, 29, 36, 38, 39, 41, 42, 45) explored the effect of ginger on 3 pain-inducing conditions. The overall finding was consistent evidence of a moderate to large beneficial analgesic effect. In female participants with dysmenorrhea, there was consistent evidence that ginger statistically significantly reduced pain severity compared with placebo (effect size: large; GRADE level: low) (45) and is as effective as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; effect size: small; GRADE level: low). Compared with placebo, the effect of ginger on dysmenorrhea pain duration was not statistically significant on meta-analysis (GRADE level: very low) (45). In participants with osteoarthritis, there was a large body of consistent evidence (meta-analyses of >700 cases and ≥4 primary studies) that ginger statistically significantly reduced pain severity and pain-related disability compared with placebo (effect size: small; GRADE level: high) (39). Although meta-analysis was not conducted, 100% (n = 2) of primary studies which assessed osteoarthritis-related knee stiffness (39) and 50% (n = 3) of studies that assessed postexercise muscle pain severity in trained and untrained participants found a statistically significant positive effect of ginger consumption (2, 38). In participants with headache or migraine, meta-analysis found no statistically significant effect of ginger on treatment response compared with placebo (GRADE level: very low) (42). No meta-analysis exploring headache/migraine severity was conducted in any review; however, the 4 (100%) primary studies which assessed headache/migraine severity found a statistically significant positive effect with ginger (2, 42).

Metabolic effects

Nine systematic reviews (2, 3, 30–32, 34, 35, 47, 48) explored the effect of ginger on 3 metabolic conditions. The overall finding was consistent evidence of a moderate to large beneficial effect for cardiovascular health, glycemic control, and weight management. With reference to cardiovascular health outcomes, there was consistent evidence that ginger reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure compared with placebo (effect size: medium to large; GRADE level: low) (31). Subgroup analyses found that only doses of >3 g/d or durations of ≤8 wk were statistically significantly effective for systolic and diastolic blood pressure but did not explain considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 94%, I2 = 81%, respectively) (31). Regarding blood lipids, there was consistent evidence that ginger compared with placebo or unspecified control statistically significantly reduced the concentration of triglycerides and total cholesterol and statistically significantly increased HDL cholesterol (effect size: small; GRADE level: very low) (32). Although 10 (71%) of the 14 studies that measured LDL cholesterol found a statistically significant positive effect of ginger, no statistical significance was found when meta-analysis was performed (GRADE level: very low) (32). Subgroup analyses improved heterogeneity and found statistically significant effects on total cholesterol (I2 = 55%) and HDL-cholesterol (I2 = 87%) only for participants with hyperlipidemia and not those with T2DM (32). In 2 (33%) of the 6 primary studies that reported on platelet aggregation, 1 (33%) of the 3 primary studies that reported on thromboxane B2 production, and no studies that measured fibrinogen or fibrinolytic activity found a statistically significant reduction with ginger consumption (2, 48). No reviews conducted meta-analysis of blood clotting outcomes.

Regarding glycemic control, there was consistent evidence that ginger compared with placebo reduced insulin resistance [measured as HOMA-IR or quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI); effect size: very large; GRADE level: moderate] (34), fasting blood glucose levels (effect size: large; GRADE level: low) (32), and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c; effect size: large; GRADE level: moderate) (35), but had no statistically significant effect on blood insulin concentrations (GRADE level: very low) (34). Subgroup analyses by population found only statistically significant effects on fasting blood glucose concentrations for participants with T2DM, but not hyperlipidemia (32).

Concerning weight management, there was some evidence that ginger in comparison with placebo reduced body weight and BMI (effect size: large; GRADE level: low) as well as hip circumference and waist-to-hip ratio (effect size: small to medium; GRADE: moderate) (34). Although meta-analyses were not conducted, 3 (75%) of the primary studies that assessed appetite, 2 (67%) of the primary studies that assessed food intake, 2 (100%) studies that measured fullness, and 3 (100%) studies that examined energy intake or thermogenesis found no statistically significant positive effects with ginger consumption (2, 30, 47).

Gastrointestinal effects

Seven systematic reviews (2, 33, 37, 40, 49, 50, 52) explored the effect of ginger on nausea and vomiting. In pregnant women, there was consistent evidence that ginger statistically significantly reduced nausea incidence and severity when compared with placebo (effect size: very large; GRADE level: high) and had no statistically significant effect on vomiting incidence (GRADE level: low) (40). Although not meta-analyzed, all 3 (100%) primary studies that assessed retching incidence in pregnant women found a statistically significant positive effect with ginger (2, 33, 40). In participants following surgical procedures, there was consistent evidence that ginger statistically significantly reduced postoperative nausea severity in comparison with placebo or unspecified control (effect size: medium; GRADE level: low) but had no statistically significant effect on nausea or vomiting incidence or demand for rescue antiemetics (GRADE level: low to moderate) (37).

In participants undergoing chemotherapy and receiving standard antiemetics, there was some evidence that adjuvant ginger consumption statistically significantly reduced likelihood of acute vomiting incidence and nausea and vomiting-related fatigue compared with placebo (effect size: small to medium; GRADE level: moderate) (49). There was a large body of evidence suggesting that ginger had no statistically significant effect on incidence or severity of overall chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting, acute nausea, delayed nausea or vomiting, or chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting-related quality of life in comparison with placebo or usual care (GRADE level: very low to moderate) (49). Subgroup analyses improved heterogeneity but did not affect the effect sizes for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting outcomes.

No reviews conducted meta-analysis of motion sickness or gastric emptying outcomes. However, 2 (67%) of the 3 studies that assessed incidence of nausea and/or vomiting related to motion sickness and 1 (50%) of the 2 studies that assessed incidence of nausea or motion sickness symptoms (vertigo and nystagmus) found a statistically significant positive effect with ginger consumption (2). Three (60%) of the 5 primary studies that measured gastric emptying and 2 (67%) of the 3 primary studies that measured induced gastric dysrhythmia found a statistically significant positive effect with ginger (2).

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects

Five systematic reviews (2, 35, 38, 44, 46) explored the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of ginger and the overall finding was consistent evidence of a moderate beneficial effect. There was consistent evidence that ginger compared with placebo or unspecified control statistically significantly reduced C-reactive protein (CRP) (46), TNF-α (44), soluble intercellular adhesion molecule (sICAM) (44), malondialdehyde (MDA), and total antioxidant capacity (TAC; effect size: unclear; GRADE level: very low to moderate) (46). There was some evidence that ginger had no statistically significant effect on prostaglandin E2 (PGE2; GRADE level: moderate) (46) or IL-6 (GRADE level: low) (44). The 3 (100%) studies that assessed IL-1 found statistically significant reductions with ginger consumption; however, no reviews conducted meta-analysis (2, 38).

Other effects

Three systematic reviews (2, 38, 43) explored other effects of ginger. The overall finding was consistent evidence of no beneficial effect on lactation as well as physical performance. All 3 (100%) primary studies that assessed range of motion and arm circumference and both (100%) studies that assessed perceived exertion during exercise found no statistically significant effect of ginger consumption (38). One (50%) of the 2 studies that measured human breast milk volume found a statistically significant increase with ginger consumption (2, 43). No reviews that examined breast milk volume or physical performance conducted meta-analyses.

Safety of ginger

Nine (60%) (29, 32, 35–37, 43, 44, 50, 51) of the 15 systematic reviews that reported on adverse events found no incidence of any adverse effect associated with ginger use (n = 32 primary studies; n = 1826 participants). In systematic reviews that did report adverse effects, the most common events reported, regardless of study population, were mild gastrointestinal side effects, mainly reflux or heartburn (2, 29, 32, 37, 40, 45, 49, 50, 52, 53), abdominal discomfort (2, 37, 39, 40, 50), and diarrhea (2, 29, 37, 50). One review (40) found reflux and abdominal discomfort to be alleviated if ginger was administered with small frequent meals. In participants undergoing chemotherapy, a meta-analysis by Crichton et al. (49) found the odds of any gastrointestinal, flushing, rash-related, or unspecified adverse event reasonably relatable to the intervention to be statistically significantly higher with oral ginger consumption (0.16–1 g/d in capsule form, 2 or 4 times daily for 5–56 d) compared with placebo (OR: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.39, 2.99; P = 0.0003; I2 = 0%; n = 3 studies; n = 5 interventions; n = 1458 participants; GRADE level: moderate). In participants with osteoarthritis, Bartels et al.’s (39) meta-analysis found participants given ginger consumption (0.5–1 g/d in capsule form for 3–12 wk) were at a 2.33 times statistically significantly higher risk of study withdrawal due to minor adverse effects (bad taste or various forms of stomach upset) compared with participants who received placebo (RR: 2.33; 95% CI: 1.04, 5.22; P = 0.04; I2 = 0%; n = 3 studies; n = 500 participants). However, in patients with dysmenorrhea, Pattanittum et al. (41) found that ginger was not statistically significantly associated with increased odds of any adverse event (OR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.13, 7.09; P = 0.09; I2 = 78%; n = 3 studies; n = 279 participants; GRADE level: low). Likewise, Crichton et al. (49) found that the odds of heartburn in chemotherapy patients was not statistically significantly different compared with placebo (OR: 1.88; 95% CI: 0.68, 5.18; P = 0.22; I2 = 0%; n = 3 studies; n = 312 participants; GRADE level: low).

Discussion

This umbrella review identified a convincing body of evidence that, in humans, ginger conferred analgesic, metabolic, and gastrointestinal therapeutic effects on a range of health conditions. The strongest evidence for therapeutic effects, with high certainty of the evidence (GRADE level: high) and very large effect size, was found for the antiemetic effects of ginger in pregnant women (1.0–2.5 g/d for 4–21 d). These findings were clinically meaningful; for example, evident by women consuming ginger being 7.5 times less likely to experience nausea than those who received placebo. Great confidence in the analgesic effects of ginger in populations with osteoarthritis was also found (0.5–1.0 g/d for 3–12 wk; GRADE level: high). Despite the effect size being small, clinical significance is suggested due to similar standardized mean differences in the treatment effect being observed with NSAIDs, which are a standard treatment for osteoarthritic pain (54). There was moderate confidence (GRADE level: moderate) in a large to very large estimated effect of ginger for glycemic control (0.05–3 g/d for 2–3 mo; GRADE level: moderate). These results were also clinically meaningful; for example, the 1% decrease in HbA1c observed in this review improves diabetes outcomes, where each 1% increase in HbA1c is associated with a 30% increase in all-cause mortality and 40% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality. Furthermore, ginger had a medium to large effect on some blood pressure, weight management, dysmenorrhea, postoperative nausea, and chemotherapy-induced vomiting outcomes, but the certainty in these effects was mostly low to moderate (0.02–3.0 g/d for 3 d to 3 mo; GRADE level: low to moderate). A statistically significant small effect of ginger was found on blood lipid profile; however, there was very low confidence in this effect (0.005–3.0 g/d for 2–3 mo; GRADE level: very low). It remains uncertain whether the health benefits of ginger were conferred, at least in part, due to anti-inflammatory and antioxidant behavior, as meta-analyses showed ginger improved CRP, TNF-α, sICAM, MDA, and TAC but there was very serious inconsistency and/or imprecision in these findings (GRADE level: very low to moderate).

Most primary studies included multiple forms of ginger consumption, but the best evidence was for ginger capsules, most likely due to ease of administering a consistent and standardized dose as well as enabling blinding via placebo capsules. Ginger supplement active constituents and frequency of ginger administration were not well reported in systematic reviews or primary studies, and studies did not include consideration of how variations in the chemical composition of ginger, and thus health effects, depend on ginger species, geographical origin, seasonal variation, storage, and harvesting and processing methods (55, 56). Therefore, conclusions on biophenol dosing cannot be made; however, dosage frequency should consider the 2-h half-life of ginger (48).

Ginger was not associated with any serious adverse events; however, despite having therapeutic effects, ginger consumption should not replace medical treatment and should only be implemented under the care of a medical physician and/or dietitian as ginger consumption may not be indicated for all populations. For example, ginger is not suitable for those with platelet disorders as studies have found ginger to reduce platelet aggregation, especially in those taking blood-thinning medications (2, 48). Ginger is also not indicated for populations susceptible to gastroesophageal reflux as heartburn was found to be a common minor side effect of ginger consumption in this review (2, 29, 32, 37, 40, 45, 49, 50, 52, 53). Ginger has been found to relax the lower esophageal sphincter, which is the primary mechanism behind reflux (57); however, minor heartburn may be improved by consuming ginger supplements with food (40). Slight abdominal discomfort, another side effect reported with ginger consumption, may actually be attributable to a sudden positive shift in the composition and function of gastrointestinal microbiota (58). Therefore, in addition to the possible direct effects on inflammatory markers, ginger may partly render anti-inflammatory effects in chronic disease populations through modulating gastrointestinal microbiota, and also may benefit healthy populations by reducing chronic inflammation which has been associated with the onset of diseases such as T2DM, heart disease, and some cancers (58, 59). The therapeutic effects of ginger in healthy populations, however, remains uncertain.

Strengths, limitations, and priorities for future research

Numerous strengths and limitations have been identified in this umbrella review. A strength of the current review is the broad scope and rigorous study design, including a thorough quality assessment of the included literature using the latest version of the AMSTAR-2 and GRADE (25, 26). However, it must be acknowledged that AMSTAR-2 and GRADE are subjective measures that do not accurately identify the specific methodological and analytical limitations of the underlying literature, as with any quality assessment tool. Another strength of this review was the extensive consideration of primary study overlap, that if unaddressed can lead to over-representation of studies and biased results and is a common limitation in umbrella reviews (27). A major limitation of this review is the possible exclusion of RCTs which have not been summarized by the included systematic reviews, which raises the possibility that key therapeutic and safety information may not be represented by the findings. Publication bias was not identified by systematic reviews as part of the AMSTAR-2 assessment but may be present due most reviews being rated poorly regarding search strategy and sample size. For example, despite many commercial ginger products aimed at motion sickness, only a small amount of studies (n = 3; n = 149 participants) were found in this review to support its use (2) and additional studies dating as far back to 1988 have been excluded (60–62). Future RCTs should be well-powered and systematic reviews should employ rigorous study designs to minimize publication bias.

As systematic review quality assessed using AMSTAR-2 and certainty in the outcome effects evaluated using GRADE was mostly very low to low, improvements in the quality of future research is needed. Systematic reviews in this review were given poor ratings mostly due to lack of detail in justifying choice of systematic review methodology, rather than the conduct of the review itself; and the primary studies represented were mostly high quality according to the diverse range of quality assessment tools used in the systematic reviews. The key limitation of the findings represented by this umbrella review were due to the heterogeneity of dose, frequency, and duration of ginger interventions, evident by high statistical heterogeneity (I2) when assessed using meta-analysis. Therefore, the quality of the reporting of systematic reviews requires improvement for more confident recommendations to be drawn and methodological rigor of systematic reviews in nutraceutical interventions is an important area for future research. Future reviews should be stringently reported according to PRISMA guidelines (21) and use best-practice methodology, such as that outlined by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (19). Future well-powered dose-dependent RCTs using ginger must test and report ginger bioactives and transparently report ginger species, intervention dose, frequency of administration, duration of intervention, and treatment compliance. Given that it is the nonvolatile bioactive compounds in ginger that are responsible for the therapeutic effects, supplements should be standardized to contain known and equal amounts of bioactive compounds (5, 56).

Outcomes for which there was insufficient or inconsistent evidence to support ginger use should be topics of future research prior to clinical use. This includes the analgesic effects of ginger on headache and migraine as well as postexercise muscle pain; metabolic effects on blood lipid profile; antiemetic effects postoperatively, during chemotherapy or relating to motion sickness; as well as the anti-inflammatory or antioxidant effects that may underpin many of the mechanisms of action. Given that most interventions identified in this review were of short duration, future research should consider the long-term effects of ginger consumption. Additional research areas of priority include the antimicrobial, immune modulating, neuroprotective, and antineoplastic, as well as liver- and kidney- protecting effects of ginger, which have been supported by a substantial number of animal and mechanistic studies yet not extensively explored in human clinical trials (3, 4).

Conclusion

Orally consumed ginger was found to be safe and confer therapeutic effects on human health and well-being, with greatest confidence in effect for antiemetic effects in pregnant women, analgesic effects in osteoarthritis, and glycemic control. Ginger was also associated with an improvement in symptoms and biomarkers of pain in populations with dysmenorrhea; metabolic conditions in terms of improving blood pressure and weight management; and gastrointestinal issues, namely postoperative nausea and chemotherapy-induced vomiting; however, there was uncertainty in the clinical relevance for these outcomes. There was substantial heterogeneity and poor reporting of ginger interventions; however, doses of 0.5–3.0 g/d in capsule form administered for up to 3 mo duration was found to be optimal across most outcomes. Future RCTs and dose-dependent trials with adequate sample sizes and standardized ginger products are warranted to better inform and standardize routine clinical prescription.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—MC, ARD, CI, WM, AL, EI, and SM: contributed to study concept and protocol development; MC and ARD: were responsible for study selection; MC, ARD, and CI: were responsible for data extraction and quality appraisal of the literature; SM: resolved conflicts with study selection, data extraction, and quality appraisal, and was responsible for GRADE assessments together with MC; MC: led data synthesis and drafting of the manuscript; ARD, CI, AL, WM, EI, and SM: revised the manuscript; SM: was responsible for study oversight and approval of the final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript. Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

As part of MC's PhD candidature, this research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Supplemental Tables 1–5 and Supplemental Figure 1 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

Abbreviations used: AMSTAR-2, Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews 2; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; CRP, C-reactive protein; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; MDA, malondialdehyde; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PROSPERO, International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; QUICKI, quantitative insulin sensitivity check index; RCT, randomized controlled trial; sICAM, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule; TAC, total antioxidant capacity; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Contributor Information

Megan Crichton, Nutrition and Dietetics Research Group, Faculty of Health Science & Medicine, Bond University, Robina, Queensland, Australia.

Alexandra R Davidson, Nutrition and Dietetics Research Group, Faculty of Health Science & Medicine, Bond University, Robina, Queensland, Australia.

Celia Innerarity, Nutrition and Dietetics Research Group, Faculty of Health Science & Medicine, Bond University, Robina, Queensland, Australia.

Wolfgang Marx, Nutrition and Dietetics Research Group, Faculty of Health Science & Medicine, Bond University, Robina, Queensland, Australia; Deakin University, Impact (the Institute for Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Translation), Food & Mood Centre, Geelong, Australia.

Anna Lohning, Nutrition and Dietetics Research Group, Faculty of Health Science & Medicine, Bond University, Robina, Queensland, Australia.

Elizabeth Isenring, Nutrition and Dietetics Research Group, Faculty of Health Science & Medicine, Bond University, Robina, Queensland, Australia.

Skye Marshall, Nutrition and Dietetics Research Group, Faculty of Health Science & Medicine, Bond University, Robina, Queensland, Australia; Department of Science, Nutrition Research Australia, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Data Availability

Data described in the manuscript will be made publicly and freely available without restriction in the Online Supplementary Material for this manuscript.

References

- 1. Liu Y, Liu J, Zhang Y. Research progress on chemical constituents of Zingiber officinale Roscoe. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2019:5370823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anh NH, Kim SJ, Long NP, Min JE, Yoon YC, Lee EG, Kim M, Kim TJ, Yang YY, Son EYet al. Ginger on human health: a comprehensive systematic review of 109 randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2020;12(1):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mao QQ, Xu XY, Cao SY, Gan RY, Corke H, Beta T, Li HB. Bioactive compounds and bioactivities of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods. 2019;8(6):185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang M, Zhao R, Wang D, Wang L, Zhang Q, Wei S, Lu F, Peng W, Wu C. Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) and its bioactive components are potential resources for health beneficial agents. Phytother Res. 2021;35(2):711–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marx W, Ried K, McCarthy AL, Vitetta L, Sali A, McKavanagh D, Isenring L. Ginger mechanism of action in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(1):141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists . The management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum. London: Green-top guideline no.69. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grossman LD, Roscoe R, Shack AR. Complementary and alternative medicine for diabetes. Canadian J Diabetes. 2018;42:S154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crichton M, Marx W, Marshall S. Cancer: nutritional implications of treatment. Practice-Based Evidence in Nutrition; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mekuria AB, Erku DA, Gebresillassie BM, Birru EM, Tizazu B, Ahmedin A. Prevalence and associated factors of herbal medicine use among pregnant women on antenatal care follow-up at University of Gondar referral and teaching hospital, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abd El-Mawla AMA. Prevalence and use of medical plants among pregnant women in Assiut Governorate. Bull Pharm Sci. 2020;43(1). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Volqvartz T, Vestergaard AL, Aagaard SK, Andreasen MF, Lesnikova I, Uldbjerg N, Larsen A, Bor P. Use of alternative medicine, ginger and licorice among Danish pregnant women – a prospective cohort study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahmed M, Hwang JH, Choi S, Han D. Safety classification of herbal medicines used among pregnant women in Asian countries: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Algarni AM, Al-Raddadi R, Alamri T. Patterns and determinants of complementary and alternative medicine use among type 2 diabetic patients in a diabetic center in Saudi Arabia: herbal alternative use in type 2 diabetes. J Fundam Appl Sci. 2017;9:1738–48. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adeniyi O, Washington L, Glenn CJ, Franklin SG, Scott A, Aung M, Niranjan SJ, Jolly PE. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among hypertensive and type 2 diabetic patients in Western Jamaica: a mixed methods study. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0245163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wazaify M, Afifi FU, El-Khateeb M, Ajlouni K. Complementary and alternative medicine use among Jordanian patients with diabetes. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tuna S, Dizdar O, Calis M. The prevalence of usage of herbal medicines among cancer patients. J Buon. 2013;18(4):1048–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crichton M, Strike K, Isenring E, McCarthy AL, Marx W, Lohning A, Marshall S. “It's natural so it shouldn't hurt me”: chemotherapy patients' perspectives, experiences, and sources of information of complementary and alternative medicines. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021;43:101362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li H, Liu Y, Luo D, Ma Y, Zhang J, Li M, Yao L, Shi X, Liu X, Yang K. Ginger for health care: an overview of systematic reviews. Complement Ther Med. 2019;45:114–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: overviews of reviews, In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Higgins JT, Thomas J., Chandler J., Cumpston M., Li T., Page M. J., Welch V. A., (eds.), 2020, Cochrane. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. In Chapter 10: Umbrella Reviews. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Aromataris E, Munn Z. (eds), 2020, Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-11. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SEet al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) . Grey matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. Ottawa: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Center for Research in Evidence-Based Practice Systematic Review Accelerator . Polyglot search translator. 2017 September 20th, 2020; Available from: http://crebp-sra.com/-/. [Google Scholar]

- 24. The EndNote Team . EndNote. Philadelphia (PA): Clarivate; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson Eet al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):380–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pieper D, Antoine S, Mathes T, Neugebauer EAM, Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Health Canada . Guidance document for preparing a submission for food health claims. Canada: Bureau of Nutritional Sciences Food Directorate, Health Products and Food Branch Health Canada; 2009. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/fn-an/alt_formats/hpfb-dgpsa/pdf/legislation/health-claims_guidance-orientation_allegations-sante-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Daily JW, Xin Z, Da Sol K, Park S. Efficacy of ginger for alleviating the symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Pain Med. 2015;16(12):2243–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ebrahimzadeh-Attari V, Malek Mahdavi A, Javadivala Z, Mahluji S, Zununi Vahed S, Ostadrahimi A. A systematic review of the anti-obesity and weight lowering effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) and its mechanisms of action. Phytother Res. 2018;32(4):577–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]