ABSTRACT

Background

Recent preclinical research strongly suggests that dietary sugars can enhance colorectal tumorigenesis by direct action, particularly in the proximal colon that unabsorbed fructose reaches.

Objectives

We aimed to examine long-term consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) and total fructose in relation to incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer (CRC) by anatomic subsite.

Methods

We followed 121,111 participants from 2 prospective US cohort studies, the Nurses’ Health Study (1984–2014) and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (1986–2014), for incident CRC and related death. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compute HRs and 95% CIs.

Results

During follow-up, we documented 2733 incident cases of CRC with a known anatomic location, of whom 901 died from CRC. Positive associations of SSB and total fructose intakes with cancer incidence and mortality were observed in the proximal colon but not in the distal colon or rectum (Pheterogeneity ≤ 0.03). SSB consumption was associated with a statistically significant increase in the incidence of proximal colon cancer (HR per 1-serving/d increment: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.34; Ptrend = 0.02) and a more pronounced elevation in the mortality of proximal colon cancer (HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.72; Ptrend = 0.002). Similarly, total fructose intake was associated with increased incidence and mortality of proximal colon cancer (HRs per 25-g/d increment: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.35; and 1.42; 95% CI: 1.12, 1.79, respectively). Moreover, SSB and total fructose intakes during the most recent 10 y, rather than those from a more distant period, were associated with increased incidence of proximal colon cancer.

Conclusions

SSB and total fructose consumption were associated with increased incidence and mortality of proximal colon cancer, particularly during later stages of tumorigenesis.

Keywords: added sugar, colorectal cancer, fructose, sucrose, sugar-sweetened beverages

See corresponding editorial on page 1453.

Introduction

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), which are sweetened by high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS; 45% glucose and 55% fructose) in the United States, are the single largest source of added sugar in Americans’ diet (1, 2). Sucrose, which is quickly digested into glucose and fructose in the small intestine, is another major source of added sugar. Whereas glucose can be metabolized throughout the entire body, fructose is mainly metabolized in the liver after absorption. Notably, moderate consumption of fructose can saturate the absorption capacity of the small intestine (3–5), leading to the direct contact of fructose with the colonic lumen of the proximal colon.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States (6). Emerging evidence suggests that CRC is a heterogeneous disease with molecular and risk factor profiles varying across anatomic subsites (7, 8). SSB and fructose consumption have been associated with increased risk of cancer recurrence and death among patients who have developed CRC (9–11), but no robust association with CRC development has been found in cohort studies (12–15). Recent preclinical research showed that HFCS administration can directly alter tumor cell metabolism and enhance tumor growth in the mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis, even in doses insufficient to cause obesity and metabolic syndrome (16). Since excess fructose reaches the proximal colon and diminishes along the colorectum, we hypothesized that SSB and sugar consumption may more strongly affect cancer development in the proximal colon. We also hypothesized that such an effect would be more pronounced for sugar consumption during a recent period, when a lesion is in place, than that from a more distant period, given the direct action of HFCS on tumor metabolism and growth (16).

In the current study, we investigated the subsite-specific association of SSB and sugar consumption with CRC incidence and mortality among participants from 2 prospective US cohort studies, the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS). With repeated dietary assessment over several decades of follow-up, we had a unique opportunity to evaluate long-term consumption of SSBs and dietary sugars in relation to CRC outcomes according to anatomic subsite and timing of consumption.

Methods

Study population

The NHS was initiated in 1976 when 121,700 US female registered nurses aged 30–55 y responded to a mailed questionnaire on risk factors for cancer and cardiovascular disease and medical history (17, 18). The HPFS was established in 1986 when 51,529 US male health professionals aged 40–75 y completed a mailed questionnaire on health-related behaviors and medical history (19). Since baseline, follow-up questionnaires have been sent to participants biennially to request an update on potential risk factors and disease diagnoses. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, and those of participating registries as required.

Outcome assessment

Participants were followed until January 2014 in the HPFS or June 2014 in the NHS. Incident cases of CRC were identified from self-report on biennial questionnaires or during follow-up of participant deaths. Deaths were ascertained through family members, the US Postal Service, or the National Death Index (20). We requested permission from participants or next of kin for descendants to acquire hospital records and pathology reports. A physician reviewed the medical records and death certificates to confirm CRC diagnosis and record information on tumor characteristics. Proximal colon cancers were defined as those that occurred in the cecum, ascending colon, or transverse colon (including the hepatic flexure); distal colon cancers as those in the descending colon (including the splenic flexure) or sigmoid colon; and rectal cancers as those in the rectosigmoid junction or rectum.

Assessment of SSB and sugar intakes

Dietary intake was assessed via validated FFQs in 1980 (61 items), 1984, 1986, and every 4 y thereafter in the NHS and every 4 y beginning in 1986 in the HPFS. Since 1984, an expanded FFQ with 131–169 items has been administered. On each FFQ, participants were asked how often, on average, they consumed a standard portion of foods and beverages (1 standard glass, bottle, or can) over the previous year, using 9 possible responses ranging from “never or less than once per month” to “6 or more times per day.” SSBs were defined as caffeinated colas, caffeine-free colas, other carbonated SSBs (i.e., noncola), and noncarbonated SSBs (fruit punches, lemonades, or other fruit drinks). Artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs) were defined as caffeinated, caffeine-free, and noncarbonated low-calorie or diet beverages.

Individual nutrient intake was calculated by multiplying the frequency of each food by its nutrient content and then summing the contributions from all foods. All nutrient values were adjusted for total energy intake by the residual method (21). Total fructose intake was calculated as free fructose intake plus half sucrose intake because sucrose, a disaccharide, is rapidly broken down into glucose and fructose in the small intestine. Added sugar included sugars eaten separately and used as ingredients in prepared or processed foods, excluding naturally occurring sugars.

The validity of the FFQ has been evaluated in a subset of participants who also completed multiple 1-wk diet records (22, 23). Reasonably high Pearson correlation coefficients between the FFQ and diet records were observed for cola (0.84) and other high-fructose foods (0.84 for orange/grapefruit juice, 0.80 for apples, 0.79 for bananas, and 0.74 for oranges).

Covariate assessment

Race was self-reported. Current weight, smoking history, diabetes history, menopausal status, and postmenopausal hormone use were initially reported at enrollment and updated biennially thereafter. Physical activity was first asked in 1986, lower gastrointestinal tract endoscopy in 1988, aspirin in 1980 in the NHS and 1986 in the HPFS, and family history of CRC in 1982 in the NHS and 1986 in the HPFS; each of these factors was updated regularly during follow-up. Total calcium and total folate intakes were calculated by summing dietary and supplemental intakes.

Statistical analysis

The study baseline was set as 1984 for the NHS (when the expanded FFQ was first administered) and 1986 for the HPFS. At baseline, we excluded participants who did not return the FFQ, left >70 blank items in the FFQ, reported implausibly high or low energy intake (<800 or >4200 kcal/d for males; <600 or >3500 kcal/d for females), or had prior history of cancer or diabetes, resulting in 121,111 participants for analyses (Supplemental Figure 1).

The main exposures were SSB and total fructose intakes (Spearman's r = 0.40) (Supplemental Table 1). Added sugar and sucrose intakes were considered secondary exposures, because their respective correlation with SSB and total fructose intakes was relatively high (Spearman's r = 0.64 and 0.81, respectively) (Supplemental Table 1). To better reflect long-term diet and reduce random error in reported intakes, we calculated the cumulative average intake by using all available FFQs from baseline until the current survey cycle, with equal weight assigned to each FFQ. SSB intake was categorized into predefined categories, and sugar intakes into sex-specific quintiles. To understand the temporal association, we also computed the average intake during the most recent 10 y (the recent period) and from >10 y ago (the distant period), by using FFQs returned within each corresponding period.

The primary outcomes were subsite-specific cancer incidence and mortality, including for the proximal colon, distal colon, and rectum. To test for a potential linear trend in the association magnitude along the colorectum, we used the meta-regression method with a subsite-specific random effect term by treating the subsite as an ordinal variable (24). In exploratory analyses, we examined cancer incidence and mortality by more refined subsites, including the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectosigmoid junction, and rectum.

The Andersen-Gill data structure was used to handle time-varying covariates, which created a new data record for every 2-y survey cycle at which a participant was at risk, with covariates updated at the time that the questionnaire was returned. HRs and 95% CIs were computed using Cox proportional hazards regression, conditioned on age and calendar year of the survey cycle. Tests for trend were performed by entering in the model the beverage/nutrient intake as a continuous variable, with statistical significance evaluated by the Wald test. Multivariable models were in addition adjusted for known and suspected risk factors for CRC, including sex; race; family history of CRC; BMI; physical activity; pack-years of smoking; alcohol intake; regular aspirin use; diabetes history; lower endoscopy; menopausal status and hormone therapy use in women; intakes of total energy, dietary fiber, total calcium, total folate, red meat, and processed meat; and Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (without SSBs and fruit juice). Subgroup analyses by covariates were performed, with heterogeneity assessed by meta-regression.

We also evaluated the association of substituting 1 serving of SSBs per day with an equivalent amount of ASBs by simultaneously including SSB and ASB intakes as continuous variables in the multivariable model. The HR for the substitution association was calculated using the difference in the 2 β-coefficients, with 95% CIs computed by their variances and covariance (25). We conducted all analyses using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All P values were 2-sided and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

The mean ± SD percentage of total energy intake from added sugar was 9.9% ± 4.4% among all cohort participants and 19.0% ± 5.5% among participants who consumed >1 serving of SSBs per day. Participants with higher SSB intake consumed an unhealthier diet, whereas those with higher total fructose intake had an overall healthier lifestyle (Table 1). Participants with higher SSB or total fructose intake both consumed less alcohol.

TABLE 1.

Age-adjusted characteristics of participants by SSB and total fructose intakes1

| SSB intake, servings | Total fructose intake2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Never | 1–3/wk | >1/d | Quintile 1 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 5 |

| Person-years for cancer incidence | 654,482 | 954,173 | 176,759 | 619,535 | 620,528 | 618,007 |

| Sugar-related intakes | ||||||

| Total energy intake from added sugar, % | 7.1 ± 3.2 | 10.3 ± 2.9 | 19.0 ± 5.5 | 6.3 ± 2.2 | 9.7 ± 2.8 | 14.3 ± 5.5 |

| SSBs, servings/d | 0 ± 0 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.8 |

| Total fructose, energy-adjusted, g/d | 37 ± 13 | 43 ± 11 | 61 ± 15 | 27 ± 5 | 42 ± 4 | 60 ± 11 |

| Sucrose, energy-adjusted, g/d | 34 ± 13 | 40 ± 12 | 51 ± 15 | 26 ± 7 | 39 ± 8 | 53 ± 13 |

| Other characteristics3 | ||||||

| Age, y | 62.4 ± 10.8 | 64.5 ± 11.1 | 60.0 ± 10.6 | 62.7 ± 10.4 | 64.2 ± 11.0 | 65.0 ± 11.4 |

| White,4 % | 95.9 | 95.1 | 92.8 | 96.2 | 95.9 | 93.0 |

| Family history of colorectal cancer, % | 13.1 | 14.2 | 13.8 | 13.5 | 14.1 | 14.1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.3 ± 4.1 | 25.3 ± 4.0 | 25.6 ± 4.5 | 25.8 ± 4.3 | 25.4 ± 4.0 | 24.8 ± 3.9 |

| Physical activity, MET-h/wk | 22.3 ± 22.7 | 21.2 ± 20.4 | 20.3 ± 21.8 | 18.8 ± 18.8 | 21.8 ± 20.8 | 22.7 ± 23.1 |

| Pack-years of smoking | 15.0 ± 20.1 | 11.6 ± 18.1 | 15.2 ± 21.9 | 18.7 ± 22.4 | 11.5 ± 17.7 | 10.4 ± 17.4 |

| Alcohol intake, g/d | 9.4 ± 13.0 | 7.4 ± 10.8 | 6.6 ± 11.6 | 14.9 ± 16.6 | 6.7 ± 9.0 | 3.7 ± 6.4 |

| Regular aspirin use (≥2 times/wk), % | 39.3 | 41.5 | 41.9 | 41.4 | 41.3 | 39.9 |

| Diabetes history, % | 5.4 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 5.7 | 4.3 |

| Ever lower endoscopy, % | 38.3 | 47.1 | 44.2 | 44.8 | 46.2 | 43.7 |

| Postmenopausal in women, % | 87.2 | 87.9 | 88.6 | 87.3 | 87.9 | 89.1 |

| Current hormone therapy use,5 % | 31.0 | 29.3 | 25.7 | 29.7 | 30.2 | 28.2 |

| Nutrient and food intakes | ||||||

| Carbohydrate, energy-adjusted, g/d | 206 ± 44 | 215 ± 36 | 237 ± 37 | 180 ± 31 | 214 ± 30 | 245 ± 37 |

| Protein, energy-adjusted, g/d | 83 ± 16 | 78 ± 14 | 70 ± 14 | 84 ± 15 | 80 ± 13 | 72 ± 14 |

| Fat, energy-adjusted, g/d | 62 ± 13 | 62 ± 12 | 60 ± 12 | 68 ± 13 | 62 ± 11 | 55 ± 10 |

| Dietary fiber, energy-adjusted, g/d | 21 ± 7 | 19 ± 5 | 16 ± 5 | 17 ± 5 | 20 ± 5 | 21 ± 7 |

| Total calcium, energy-adjusted, mg/d | 1082 ± 460 | 986 ± 365 | 807 ± 312 | 984 ± 398 | 1028 ± 391 | 981 ± 419 |

| Total folate, energy-adjusted, μg/d | 519 ± 260 | 482 ± 211 | 416 ± 192 | 448 ± 214 | 496 ± 218 | 511 ± 242 |

| Red meat, servings/wk | 4.0 ± 2.9 | 4.9 ± 2.8 | 5.7 ± 3.1 | 5.7 ± 3.2 | 4.7 ± 2.7 | 3.6 ± 2.4 |

| Processed meat, servings/wk | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 2.2 ± 1.9 | 3.0 ± 2.7 | 2.5 ± 2.4 | 2.0 ± 1.9 | 1.6 ± 1.7 |

| Vegetables, servings/d | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 3.4 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 3.6 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 1.9 |

| Fruit, servings/d | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 1.4 |

| Fruit juice, servings/d | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.9 |

| AHEI-20106 | 52 ± 10 | 48 ± 9 | 43 ± 9 | 46 ± 9 | 50 ± 9 | 51 ± 10 |

Values are mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. Proportions calculated among all participants unless otherwise specified. AHEI, Alternate Healthy Eating Index; MET, metabolic equivalent; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Calculated as free fructose intake plus half sucrose intake and adjusted for total energy intake.

All values other than age standardized to the age distribution of the study population.

Missing among 1.9% of participants.

Proportions calculated in postmenopausal women.

Without SSBs and fruit juice (range: 0–100).

During follow-up (30 y in the NHS and 28 y in the HPFS among those alive and free of CRC), we documented 2733 incident cases of CRC with available anatomic location data, of whom 901 died from CRC, including 1275 in the proximal colon (409 deaths), 835 in the distal colon (266 deaths), and 623 in the rectum (226 deaths). The median age at diagnosis was 72 y (IQR: 64–77 y) for proximal colon cancer, 69 y (63–75 y) for distal colon cancer, and 69 y (63–76 y) for rectal cancer.

Overall association

SSB and total fructose intakes were not associated with overall CRC incidence (Tables 2 and 3, respectively). However, total fructose intake, but not SSB intake, was associated with overall CRC mortality, with an HR per 25-g/d increment of 1.20 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.38; Ptrend = 0.01).

TABLE 2.

Association of SSB intake with CRC incidence and mortality according to main anatomic location1

| SSB intake, servings | 1-Serving/d increment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Never | <1/wk | 1–3/wk | 4–7/wk | >1/d | P trend 2 | |

| Mean ± SD intake, servings/d | 0 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | ||

| Cancer incidence | |||||||

| Person-years | 654,482 | 902,877 | 954,173 | 410,798 | 176,759 | ||

| Overall3 | |||||||

| Cases, n | 614 | 909 | 969 | 392 | 134 | ||

| HR (95% CI)4 | 1 | 1.03 (0.92, 1.14) | 1.13 (1.02, 1.26) | 1.18 (1.03, 1.34) | 1.10 (0.91, 1.34) | 1.09 (1.00, 1.18) | 0.05 |

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 1.08 (0.97, 1.20) | 1.16 (1.04, 1.29) | 1.15 (1.00, 1.32) | 1.04 (0.85, 1.27) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.12) | 0.57 |

| Proximal colon | |||||||

| Cases, n | 233 | 421 | 388 | 172 | 61 | ||

| HR (95% CI)4 | 1 | 1.19 (1.01, 1.40) | 1.13 (0.95, 1.33) | 1.32 (1.07, 1.62) | 1.35 (1.01, 1.81) | 1.18 (1.04, 1.33) | 0.01 |

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 1.22 (1.03, 1.44) | 1.17 (0.99, 1.39) | 1.36 (1.09, 1.68) | 1.38 (1.01, 1.88) | 1.18 (1.03, 1.34) | 0.02 |

| Distal colon | |||||||

| Cases, n | 190 | 232 | 275 | 105 | 33 | ||

| HR (95% CI)4 | 1 | 0.94 (0.77, 1.15) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.37) | 1.10 (0.86, 1.41) | 0.90 (0.61, 1.32) | 0.97 (0.82, 1.15) | 0.73 |

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.99 (0.81, 1.21) | 1.12 (0.92, 1.37) | 1.03 (0.79, 1.33) | 0.81 (0.54, 1.20) | 0.88 (0.73, 1.06) | 0.17 |

| Rectum | |||||||

| Cases, n | 138 | 180 | 206 | 75 | 24 | ||

| HR (95% CI)4 | 1 | 0.91 (0.72, 1.14) | 1.08 (0.86, 1.35) | 0.95 (0.71, 1.27) | 0.79 (0.50, 1.24) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.18) | 0.78 |

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.95 (0.76, 1.20) | 1.08 (0.86, 1.36) | 0.89 (0.65, 1.21) | 0.70 (0.44, 1.12) | 0.89 (0.72, 1.09) | 0.26 |

| Pheterogeneity across subsites6 = 0.009 | |||||||

| Cancer mortality | |||||||

| Person-years | 658,146 | 911,331 | 963,232 | 414,084 | 177,832 | ||

| Overall7 | |||||||

| Deaths, n | 200 | 317 | 328 | 141 | 52 | ||

| HR (95% CI)4 | 1 | 0.95 (0.80, 1.14) | 1.05 (0.87, 1.26) | 1.28 (1.02, 1.60) | 1.33 (0.97, 1.83) | 1.23 (1.07, 1.41) | 0.004 |

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.99 (0.82, 1.18) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.25) | 1.20 (0.95, 1.52) | 1.18 (0.84, 1.65) | 1.12 (0.97, 1.30) | 0.13 |

| Proximal colon | |||||||

| Deaths, n | 65 | 142 | 121 | 53 | 28 | ||

| HR (95% CI)4 | 1 | 1.27 (0.94, 1.71) | 1.14 (0.83, 1.55) | 1.40 (0.96, 2.04) | 2.09 (1.31, 3.32) | 1.40 (1.15, 1.69) | 0.0006 |

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 1.31 (0.97, 1.77) | 1.16 (0.84, 1.60) | 1.43 (0.96, 2.11) | 2.09 (1.28, 3.43) | 1.39 (1.13, 1.72) | 0.002 |

| Distal colon | |||||||

| Deaths, n | 57 | 70 | 87 | 39 | 13 | ||

| HR (95% CI)4 | 1 | 0.78 (0.55, 1.12) | 1.03 (0.73, 1.45) | 1.31 (0.86, 2.00) | 1.19 (0.64, 2.23) | 1.12 (0.85, 1.50) | 0.42 |

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.78 (0.55, 1.12) | 0.94 (0.66, 1.35) | 1.12 (0.72, 1.75) | 0.98 (0.51, 1.90) | 0.97 (0.70, 1.34) | 0.85 |

| Rectum | |||||||

| Deaths, n | 48 | 66 | 73 | 31 | 8 | ||

| HR (95% CI)4 | 1 | 0.83 (0.57, 1.21) | 0.97 (0.67, 1.42) | 1.15 (0.72, 1.84) | 0.83 (0.39, 1.80) | 1.10 (0.79, 1.52) | 0.58 |

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.85 (0.58, 1.25) | 0.96 (0.65, 1.42) | 1.04 (0.64, 1.71) | 0.63 (0.28, 1.42) | 0.92 (0.64, 1.31) | 0.65 |

| Pheterogeneity across subsites6 = 0.02 | |||||||

CRC, colorectal cancer; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Test for trend performed by entering the intake as a continuous variable in the model.

Including 285 incident cases of CRC with an unknown site.

From Cox proportional hazards regression conditioned on age and calendar year of the survey cycle and adjusted for total energy intake (quintiles by sex).

In addition adjusted for sex; race (white, nonwhite, or unknown); family history of CRC (yes or no); BMI (in kg/m2) (<25.0, 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, ≥35.0, or missing); physical activity (quintiles by sex); pack-years of smoking (0, 1–4, 5–19, 20–39, ≥40, or missing); alcohol intake (g/d) (0, 0.1–4.9, 5.0–14.9, 15.0–29.9, or ≥30.0); regular aspirin use (yes or no); diabetes history (yes or no); lower endoscopy (never or ever); menopausal status and hormone therapy use in women (premenopausal, postmenopausal never user, postmenopausal past user, postmenopausal current user, or unknown); intakes of dietary fiber, total calcium, total folate, red meat, and processed meat (quintiles by sex); and Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (without SSBs and fruit juice; quintiles by sex).

Calculated by the meta-regression method with a subsite-specific random effect term by treating the subsite as an ordinal variable (proximal colon = 1; distal colon = 2; rectum = 3), using multivariable HRs per 1-serving/d increment in SSB intake.

Including 137 deaths from CRC with an unknown site.

TABLE 3.

Association of total fructose intake with CRC incidence and mortality according to main anatomic location1

| Total fructose intake2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | 25-g/d increment | P trend 3 |

| Mean ± SD intake, g/d | 27 ± 5 | 36 ± 4 | 42 ± 4 | 48 ± 5 | 60 ± 11 | ||

| Cancer incidence | |||||||

| Person-years | 619,535 | 620,973 | 620,528 | 620,046 | 618,007 | ||

| Overall4 | |||||||

| Cases, n | 613 | 600 | 590 | 597 | 618 | ||

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.92 (0.82, 1.03) | 0.86 (0.76, 0.96) | 0.84 (0.75, 0.94) | 0.84 (0.75, 0.94) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 0.75 |

| HR (95% CI)6 | 1 | 1.03 (0.92, 1.16) | 1.03 (0.91, 1.16) | 1.05 (0.93, 1.19) | 1.09 (0.96, 1.24) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.16) | 0.14 |

| Proximal colon | |||||||

| Cases, n | 243 | 233 | 272 | 269 | 258 | ||

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.89 (0.74, 1.06) | 0.97 (0.82, 1.16) | 0.93 (0.78, 1.11) | 0.88 (0.73, 1.05) | 0.95 (0.85, 1.06) | 0.37 |

| HR (95% CI)6 | 1 | 1.00 (0.83, 1.21) | 1.17 (0.97, 1.41) | 1.19 (0.98, 1.44) | 1.17 (0.95, 1.43) | 1.18 (1.03, 1.35) | 0.02 |

| Distal colon | |||||||

| Cases, n | 177 | 169 | 155 | 164 | 170 | ||

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.90 (0.73, 1.11) | 0.80 (0.64, 0.99) | 0.81 (0.65, 1.00) | 0.82 (0.66, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.11) | 0.66 |

| HR (95% CI)6 | 1 | 0.98 (0.79, 1.22) | 0.92 (0.73, 1.15) | 0.95 (0.75, 1.21) | 0.98 (0.76, 1.25) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) | 0.83 |

| Rectum | |||||||

| Cases, n | 135 | 139 | 116 | 113 | 120 | ||

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.98 (0.77, 1.25) | 0.79 (0.62, 1.02) | 0.75 (0.58, 0.96) | 0.77 (0.60, 0.99) | 0.86 (0.73, 1.01) | 0.07 |

| HR (95% CI)6 | 1 | 1.11 (0.87, 1.42) | 0.95 (0.73, 1.24) | 0.93 (0.70, 1.22) | 0.96 (0.72, 1.27) | 0.88 (0.73, 1.06) | 0.18 |

| Pheterogeneity across subsites7 = 0.009 | |||||||

| Cancer mortality | |||||||

| Person-years | 624,668 | 626,113 | 625,585 | 625,183 | 623,076 | ||

| Overall8 | |||||||

| Deaths, n | 210 | 179 | 201 | 202 | 246 | ||

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.78 (0.64, 0.96) | 0.81 (0.67, 0.99) | 0.78 (0.64, 0.94) | 0.91 (0.76, 1.10) | 1.06 (0.94, 1.20) | 0.33 |

| HR (95% CI)6 | 1 | 0.88 (0.72, 1.08) | 0.98 (0.80, 1.21) | 0.98 (0.79, 1.22) | 1.21 (0.97, 1.50) | 1.20 (1.04, 1.38) | 0.01 |

| Proximal colon | |||||||

| Deaths, n | 82 | 63 | 82 | 80 | 102 | ||

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.70 (0.51, 0.98) | 0.86 (0.64, 1.18) | 0.80 (0.59, 1.10) | 0.99 (0.74, 1.33) | 1.03 (0.84, 1.25) | 0.79 |

| HR (95% CI)6 | 1 | 0.81 (0.58, 1.14) | 1.09 (0.78, 1.51) | 1.12 (0.80, 1.58) | 1.51 (1.07, 2.13) | 1.42 (1.12, 1.79) | 0.003 |

| Distal colon | |||||||

| Deaths, n | 54 | 46 | 52 | 49 | 65 | ||

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.78 (0.53, 1.16) | 0.80 (0.55, 1.18) | 0.70 (0.48, 1.04) | 0.94 (0.65, 1.36) | 1.05 (0.82, 1.34) | 0.71 |

| HR (95% CI)6 | 1 | 0.81 (0.54, 1.22) | 0.86 (0.57, 1.30) | 0.77 (0.50, 1.18) | 1.04 (0.68, 1.59) | 1.05 (0.79, 1.40) | 0.73 |

| Rectum | |||||||

| Deaths, n | 43 | 44 | 48 | 46 | 45 | ||

| HR (95% CI)5 | 1 | 0.94 (0.62, 1.43) | 0.96 (0.63, 1.45) | 0.88 (0.58, 1.34) | 0.81 (0.53, 1.24) | 0.93 (0.71, 1.22) | 0.61 |

| HR (95% CI)6 | 1 | 1.08 (0.70, 1.68) | 1.11 (0.71, 1.74) | 1.04 (0.65, 1.65) | 0.96 (0.59, 1.55) | 0.95 (0.69, 1.30) | 0.75 |

| Pheterogeneity across subsites7 = 0.03 | |||||||

CRC, colorectal cancer.

Calculated as free fructose intake plus half sucrose intake and adjusted for total energy intake.

Test for trend performed by entering the intake as a continuous variable in the model.

Including 285 incident cases of CRC with an unknown site.

From Cox proportional hazards regression conditioned on age and calendar year of the survey cycle.

Conditioned on and adjusted for the same variables as in the multivariable model in Table 2.

Calculated by the meta-regression method with a subsite-specific random effect term by treating the subsite as an ordinal variable (proximal colon = 1; distal colon = 2; rectum = 3), using multivariable HRs per 25-g/d increment in total fructose intake.

Including 137 deaths from CRC with an unknown site.

Subsite-specific association

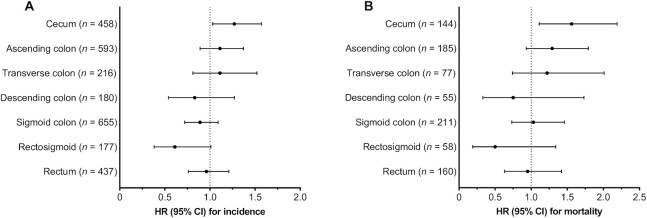

SSB intake was associated with a statistically significant increase in the incidence of proximal colon cancer (HR per 1-serving/d increment: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.34; Ptrend = 0.02) and a more pronounced elevation in the mortality of proximal colon cancer (HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.72; Ptrend = 0.002) (Table 2). Similar results were observed when SSB intake was analyzed as a categorical variable. Compared with never drinkers, participants who consumed >1 serving of SSBs per day had HRs of 1.38 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.88) and 2.09 (95% CI: 1.28, 3.43) for incidence and mortality of proximal colon cancer, respectively. Further analysis of more refined subsites showed that the positive association between SSB intake and proximal colon cancer was strongest for the cecum, the first segment in the proximal colon that unabsorbed fructose reaches (HRs per 1-serving/d increment: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.57 for incidence and 1.56; 95% CI: 1.11, 2.19 for mortality) (Figure 1). In contrast, SSB intake was not associated with cancer incidence and mortality in the distal colon or rectum, with evidence of subsite heterogeneity (Pheterogeneity = 0.009 for incidence and 0.02 for mortality) (Table 2). We also estimated that substituting 1 serving of SSBs per day with an equivalent amount of ASBs was associated with reductions of 18.7% (95% CI: 5.3%, 30.1%) and 25.3% (95% CI: 5.0%, 41.3%) in the incidence and mortality of proximal colon cancer, respectively, but not associated with lower incidence or mortality of distal colon or rectal cancer (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Association of SSB intake with (A) incidence and (B) mortality of colorectal cancer according to refined anatomic location. The sample size was the same as that in Tables 2 and 3. HRs and 95% CIs associated with a 1-serving/d increment in SSB intake were presented, estimated by Cox proportional hazards regression conditioned on and adjusted for the same variables as in the multivariable model in Table 2. SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Similar to the foregoing findings, positive associations of added sugar intake with CRC incidence and mortality were observed only for proximal colon cancer (Pheterogeneity = 0.001 for incidence and 0.01 for mortality), with HRs per 5% increment in total energy intake from added sugar of 1.13 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.22; Ptrend = 0.001) and 1.17 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.33; Ptrend = 0.02), respectively (Supplemental Table 2).

As with SSB and added sugar intakes, total fructose intake was positively associated with incidence and mortality of proximal colon cancer, with HRs per 25-g/d increment of 1.18 (95% CI: 1.03, 1.35; Ptrend = 0.02) and 1.42 (95% CI: 1.12, 1.79; Ptrend = 0.003), respectively (Table 3). Sucrose intake was significantly associated with incidence but not mortality of proximal colon cancer, with respective HRs of 1.14 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.30; Ptrend = 0.04) and 1.19 (95% CI: 0.95, 1.49; Ptrend = 0.13) (Supplemental Table 3). The foregoing associations remained similar after additional adjustment for fruit intake (data not shown). In contrast, no association was found between total fructose or sucrose intake and incidence or mortality of distal colon or rectal cancer (e.g., total fructose: Pheterogeneity = 0.009 for incidence and 0.03 for mortality).

Temporal association

During the entire follow-up, the intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.41 for repeated measures of SSB intake and 0.51 for total fructose intake, indicating modest to moderate variation in an individual's long-term diet. Consistently, SSB and sugar intakes during the most recent 10 y (recent intakes) were moderately correlated with those from >10 y ago (remote intakes) (Spearman's r = 0.55 for SSB intake and 0.61 for total fructose intake). In models mutually adjusted for intakes during the 2 periods, recent SSB (per 1-serving/d increment) and total fructose (per 25-g/d increment) intakes were associated with increased incidence of proximal colon cancer (HRs: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.31; Ptrend = 0.04 and 1.23; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.40; Ptrend = 0.002, respectively), whereas no association with remote intakes was observed (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Temporal association of SSB and total fructose intakes with incidence of proximal colon cancer1

| Recent intake (≤10 y) | Remote intake (>10 y) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Person-years | Cases, n | HR (95% CI)2 | P trend 3 | Person-years | Cases, n | HR (95% CI)2 | P trend 3 |

| SSB intake | ||||||||

| Never | 843,143 | 320 | 1 | 493,225 | 253 | 1 | ||

| ≤3 Servings/wk | 1,590,126 | 708 | 1.22 (1.06, 1.40) | 987,933 | 487 | 1.00 (0.85, 1.18) | ||

| ≥4 Servings/wk | 544,198 | 215 | 1.25 (1.02, 1.52) | 359,419 | 172 | 1.12 (0.90, 1.39) | ||

| 1-Serving/d increment | 1.15 (1.01, 1.31) | 0.04 | 1.03 (0.89, 1.19) | 0.66 | ||||

| Total fructose intake4 | ||||||||

| Quintile 1 | 595,960 | 217 | 1 | 367,948 | 198 | 1 | ||

| Quintiles 2–3 | 1,193,340 | 502 | 1.22 (1.03, 1.45) | 737,214 | 346 | 0.88 (0.73, 1.06) | ||

| Quintiles 4–5 | 1,188,168 | 524 | 1.29 (1.07, 1.55) | 735,415 | 368 | 0.94 (0.77, 1.14) | ||

| 25-g/d increment | 1.23 (1.08, 1.40) | 0.002 | 0.94 (0.81, 1.09) | 0.43 | ||||

SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

From Cox proportional hazards regression conditioned on and adjusted for the same variables as in the multivariable model in Table 2. Recent and remote intakes were mutually adjusted.

Test for trend performed by entering the intake as a continuous variable in the model.

Calculated as free fructose intake plus half sucrose intake and adjusted for total energy intake.

Subgroup analyses

We examined whether associations of SSB and total fructose intakes with incidence and mortality of proximal colon cancer differed by covariates and did not find significant heterogeneity by age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol intake, and fruit intake (Supplemental Table 4). Because studies suggest that dietary sugars may promote CRC development among individuals with insulin resistance (26, 27), we also examined associations by combined categories of BMI and physical activity (Supplemental Table 5). The association between SSB intake and incidence of proximal colon cancer appeared to be stronger among those who were both overweight and sedentary (i.e., generally at higher risk of insulin resistance), but no significant heterogeneity was found (Pheterogeneity = 0.20).

Discussion

In this large prospective study, we found that higher intakes of SSBs, total fructose, sucrose, and added sugar were associated with a moderate increase in the incidence of, and a more pronounced elevation in the mortality of, proximal colon cancer. Moreover, SSB and total fructose intakes during the most recent 10 y, rather than those from a more distant period, were associated with increased incidence of proximal colon cancer. In contrast, no association was found between SSB or sugar consumption and incidence or mortality of distal colon or rectal cancer.

Although an association between higher sugar intake and increased risk of CRC has been well documented in case-control studies (28), most prospective cohort studies have found no such association overall and by anatomic subsite, including a meta-analysis of 6 cohorts examining fructose and sucrose intakes (15) and a pooled analysis of 13 cohorts examining SSB intake (12). One possible explanation is that in most cohorts, dietary intakes were assessed at the time of participant enrollment, which could be decades before cancer diagnosis and may not have captured long-term exposure. A unique advantage of our study design is that we assessed dietary intakes not only at enrollment but in a repeated manner throughout follow-up, such that we were able to examine long-term average amounts of dietary intakes, as well as intakes with different latency periods. By mutually adjusting for remote and recent intakes, we showed that only recent SSB and total fructose intakes were associated with increased incidence of proximal colon cancer. Furthermore, SSB and total fructose intakes had more pronounced associations with the mortality than with the incidence of proximal colon cancer. Together, these data suggest that dietary sugars may act during later stages of colorectal tumorigenesis.

In this study, the association of SSB and sugar consumption with cancer incidence and mortality was restricted to the proximal colon, particularly the cecum, the location closest to the small intestine, which could at least partly be explained by the direct proneoplastic action of unabsorbed fructose that reaches the colon. Hydrogen breath tests demonstrate that as little as 5–25 g of fructose can overwhelm the absorptive capability of the small intestine in some healthy adults (3–5). Animal research has elucidated how fructose alters tumor cell metabolism and promotes colon cancer growth (16). Specifically, colon tumors express high concentrations of several key enzymes in fructose absorption (e.g., the fructose transporter GLUT5) and metabolism (e.g., ketohexokinase), such that fructose is trapped by the tumors, instead of being transported to the liver and blood, and converted into fructose-1-phosphate that in turn activates glycolysis and de novo lipogenesis to support tumor growth. As a result, HFCS treatment significantly increases the number of large adenomas and high-grade tumors in APC mutant mice, a mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis. Importantly, such direct tumor-enhancing mechanisms are independent of obesity and metabolic syndrome caused by sugar consumption (16, 29).

Another long-standing hypothesis on the oncogenic potential of dietary sugars relates to their contribution to systemic hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia, which have been implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis (30, 31). Specifically, high glucose elicits rapid insulin release from pancreatic β cells, and a high flux of fructose to the liver, the main site of fructose metabolism, enhances triglyceride synthesis that in turn promotes hepatic and systemic insulin resistance (32). Interestingly, animal research has shown that small doses of fructose can be metabolized in the small intestine to glucose and organic acids, rather than being transported to the liver and metabolized there (33, 34). If confirmed in humans, this would suggest that the small intestine can protect the liver from the adverse effects of fructose by metabolizing a certain amount of fructose. In our study, the association between SSB intake and incidence of proximal colon cancer was not significantly stronger among overweight and sedentary individuals who are generally at higher risk of insulin resistance. Further research is needed to study the potential synergy between sugar consumption and insulin resistance that promotes CRC development.

The strengths of this study include the prospective design precluding recall bias, large sample size, long follow-up period, repeated measures of diet, and detailed data on many potential confounders. Limitations of this study also deserve consideration. First, we were unable to examine the risk for individuals with very high consumption, although added sugar intake in the highest category of our population was similar to the US average (35), which is considered high. Second, dietary intakes were self-reported by participants and thus susceptible to measurement error. However, the validity of the FFQ has been established by comparison with diet records, and calculation of the cumulative average intake to better reflect long-term intake can reduce random measurement error in reporting of dietary intakes. Third, despite adjustment for a variety of known and suspected CRC risk factors, residual and unmeasured confounding (e.g., eating at fast-food restaurants) cannot be completely ruled out as in other observational studies. Fourth, multiple comparisons were performed, and thus some of the findings may be due to chance. However, exposures examined in this study were correlated, and we a priori hypothesized that the association would be stronger for proximal colon cancer. Finally, our study participants are predominantly individuals of European descent, and our findings may not be generalizable to racially and ethnically more diverse populations.

In conclusion, SSB and total fructose consumption were associated with increased incidence and mortality of proximal colon cancer, particularly during later stages of tumorigenesis. Although requiring confirmation in other large cohorts, these observational data support findings from a recent animal study that suggested a direct tumor-enhancing role of dietary sugars in colorectal tumorigenesis. Furthermore, our results provide further support for current dietary guidelines and policies to limit SSB consumption to improve the health of the general population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study for their valuable contributions and the cancer registries of the following states for their help: AL, AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, IA, ID, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, NC, ND, NE, NH, NJ, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—CY, ELG, and KW: conceived and designed the study; CY: acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and performed statistical analysis; H-KJ: verified the data; MS, XZ, ATC, SO, KN, and KW: obtained funding; ELG and KW: provided supervision; CY, H-KJ, ELG, and KW: had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; and all authors: critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript. ATC declares research funding from Bayer and consulting for Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer. JAM declares research funding from Boston Biomedical and consulting for Cota Healthcare and Taiho Pharmaceutical. KN declares research funding from Evergrande Group, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pharmavite, and Revolution Medicines; advisory board participation for Array Biopharma, BiomX, and Seattle Genetics; and consulting for X-Biotix Therapeutics. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

The Nurses’ Health Study is supported by NIH grants UM1 CA186107 and P01 CA87969. The Health Professionals Follow-Up Study is supported by NIH grant U01 CA167552. This work was in addition supported by NIH grant K99/R00 CA215314 (to MS), American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar grant MRSG-17-220-01—NEC (to MS), NIH grant K07 CA188126 (to XZ), American Cancer Society Research Scholar grant RSG NEC-130476 (to XZ), NIH grants K24 DK098311 and R35 CA253185 (to ATC), NIH grants R35 CA197735 and R21 CA230873 (to SO), NIH grant R01 CA205406 (to KN), NIH grants R03 CA197879, R21 CA222940, and R21 CA230873 (to KW), and an American Institute for Cancer Research Investigator-Initiated Research Grant (to KW).

Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Tables 1–5 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

ELG and KW contributed equally to this work as senior authors.

Abbreviations used: ASB, artificially sweetened beverage; CRC, colorectal cancer; HFCS, high-fructose corn syrup; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-Up Study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

Contributor Information

Chen Yuan, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Hee-Kyung Joh, Department of Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea; Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea; Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Qiao-Li Wang, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Yin Zhang, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Stephanie A Smith-Warner, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Molin Wang, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Biostatistics, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Mingyang Song, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Clinical and Translational Epidemiology Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Yin Cao, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA; Alvin J Siteman Cancer Center, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA; Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Xuehong Zhang, Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Emilie S Zoltick, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Jinhee Hur, Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Food Science and Biotechnology, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, Republic of Korea.

Andrew T Chan, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Clinical and Translational Epidemiology Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Jeffrey A Meyerhardt, Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Shuji Ogino, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA; Program in Molecular Pathological Epidemiology, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Cancer Immunology and Cancer Epidemiology Programs, Dana-Farber Harvard Cancer Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Kimmie Ng, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Edward L Giovannucci, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Kana Wu, Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Data Availability

Data described in the article, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending approval by the Channing Division of Network Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Further information including the procedures to obtain and access data from the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study is described at https://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/researchers (contact e-mail: nhsaccess@channing.harvard.edu) and https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/hpfs/for-collaborators/.

References

- 1. Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, Howard BV, Lefevre M, Lustig RH, Sacks F, Steffen LM, Wylie-Rosett J. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120(11):1011–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guthrie JF, Morton JF. Food sources of added sweeteners in the diets of Americans. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(1):43–51., quiz 49–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ravich WJ, Bayless TM, Thomas M. Fructose: incomplete intestinal absorption in humans. Gastroenterology. 1983;84(1):26–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beyer PL, Caviar EM, McCallum RW. Fructose intake at current levels in the United States may cause gastrointestinal distress in normal adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(10):1559–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rumessen JJ, Gudmand-Hoyer E. Absorption capacity of fructose in healthy adults. Comparison with sucrose and its constituent monosaccharides. Gut. 1986;27(10):1161–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamauchi M, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, Qian ZR, Nishihara R, Liao X, Waldron L, Hoshida Y, Huttenhower Cet al. Assessment of colorectal cancer molecular features along bowel subsites challenges the conception of distinct dichotomy of proximal versus distal colorectum. Gut. 2012;61(6):847–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang L, Lo CH, He X, Hang D, Wang M, Wu K, Chan AT, Ogino S, Giovannucci EL, Song M. Risk factor profiles differ for cancers of different regions of the colorectum. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):241–56.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meyerhardt JA, Sato K, Niedzwiecki D, Ye C, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Mowat RB, Whittom R, Hantel A, Benson Aet al. Dietary glycemic load and cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(22):1702–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fuchs MA, Sato K, Niedzwiecki D, Ye X, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Mowat RB, Whittom R, Hantel A, Benson Aet al. Sugar-sweetened beverage intake and cancer recurrence and survival in CALGB 89803 (Alliance). PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zoltick ES, Smith-Warner SA, Yuan C, Wang M, Fuchs CS, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Ng K, Ogino S, Stampfer MJet al. Sugar-sweetened beverage, artificially sweetened beverage and sugar intake and colorectal cancer survival. Br J Cancer. 2021;125(7):1016–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang X, Albanes D, Beeson WL, van den Brandt PA, Buring JE, Flood A, Freudenheim JL, Giovannucci EL, Goldbohm RA, Jaceldo-Siegl Ket al. Risk of colon cancer and coffee, tea, and sugar-sweetened soft drink intake: pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(11):771–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hodge AM, Bassett JK, Milne RL, English DR, Giles GG. Consumption of sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened soft drinks and risk of obesity-related cancers. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(9):1618–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pacheco LS, Anderson CAM, Lacey JV Jr, Giovannucci EL, Lemus H, Araneta MRG, Sears DD, Talavera GA, Martinez ME. Sugar-sweetened beverages and colorectal cancer risk in the California Teachers Study. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aune D, Chan DSM, Lau R, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, Norat T. Carbohydrates, glycemic index, glycemic load, and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(4):521–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goncalves MD, Lu C, Tutnauer J, Hartman TE, Hwang S-K, Murphy CJ, Pauli C, Morris R, Taylor S, Bosch Ket al. High-fructose corn syrup enhances intestinal tumor growth in mice. Science. 2019;363(6433):1345–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Belanger CF, Hennekens CH, Rosner B, Speizer FE. The nurses’ health study. Am J Nurs. 1978;78(6):1039–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Colditz GA, Philpott SE, Hankinson SE. The impact of the Nurses’ Health Study on population health: prevention, translation, and control. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1540–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, Rosner B, Stampfer MJ. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of coronary disease in men. Lancet. 1991;338(8765):464–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sathiakumar N, Delzell E, Abdalla O. Using the National Death Index to obtain underlying cause of death codes. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40(9):808–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4):1220S–8S.; discussion 1229S–31S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Willett WC. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(4):858–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93(7):790–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang M, Spiegelman D, Kuchiba A, Lochhead P, Kim S, Chan AT, Poole EM, Tamimi R, Tworoger SS, Giovannucci Eet al. Statistical methods for studying disease subtype heterogeneity. Stat Med. 2016;35(5):782–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Malik VS, Li Y, Pan A, De Koning L, Schernhammer E, Willett WC, Hu FB. Long-term consumption of sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of mortality in US adults. Circulation. 2019;139(18):2113–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Michaud DS, Fuchs CS, Liu S, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E. Dietary glycemic load, carbohydrate, sugar, and colorectal cancer risk in men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(1):138–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCarl M, Harnack L, Limburg PJ, Anderson KE, Folsom AR. Incidence of colorectal cancer in relation to glycemic index and load in a cohort of women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(5):892–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yuan C, Giovannucci EL. Epidemiological evidence for dietary sugars and colorectal cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2020;16(3):55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tappy L. Fructose-containing caloric sweeteners as a cause of obesity and metabolic disorders. J Exp Biol. 2018;221(Pt Suppl 1):jeb164202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsai CJ, Giovannucci EL. Hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, vitamin D, and colorectal cancer among whites and African Americans. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(10):2497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pakiet A, Kobiela J, Stepnowski P, Sledzinski T, Mika A. Changes in lipids composition and metabolism in colorectal cancer: a review. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Basciano H, Federico L, Adeli K. Fructose, insulin resistance, and metabolic dyslipidemia. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2005;2(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jang C, Hui S, Lu W, Cowan AJ, Morscher RJ, Lee G, Liu W, Tesz GJ, Birnbaum MJ, Rabinowitz JD. The small intestine converts dietary fructose into glucose and organic acids. Cell Metab. 2018;27(2):351–61.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jang C, Wada S, Yang S, Gosis B, Zeng X, Zhang Z, Shen Y, Lee G, Arany Z, Rabinowitz JD. The small intestine shields the liver from fructose-induced steatosis. Nat Metab. 2020;2(7):586–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Powell ES, Smith-Taillie LP, Popkin BM. Added sugars intake across the distribution of US children and adult consumers: 1977–2012. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(10):1543–50.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the article, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending approval by the Channing Division of Network Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Further information including the procedures to obtain and access data from the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study is described at https://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/researchers (contact e-mail: nhsaccess@channing.harvard.edu) and https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/hpfs/for-collaborators/.