Abstract

The aim is to explore the predictive value of salivary bacteria for the presence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Saliva samples were obtained from 178 patients with ESCC and 101 healthy controls, and allocated to screening and verification cohorts, respectively. In the screening phase, after saliva DNA was extracted, 16S rRNA V4 regions of salivary bacteria were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with high-throughput sequencing. Highly expressed target bacteria were screened by Operational Taxonomic Units clustering, species annotation and microbial diversity assessment. In the verification phase, the expression levels of target bacteria identified in the screening phase were verified by absolute quantitative PCR (Q-PCR). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted to investigate the predictive value of target salivary bacteria. LEfSe analysis revealed higher proportions of Fusobacterium, Streptococcus and Porphyromonas, and Q-PCR assay showed significantly higher numbers of Streptococcus salivarius, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis in patients with ESCC, when compared with healthy controls (all P < 0.05). The areas under the ROC curves for Streptococcus salivarius, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis and the combination of the three bacteria for predicting patients with ESCC were 69%, 56.5%, 61.8% and 76.4%, respectively. The sensitivities corresponding to cutoff value were 69.3%, 22.7%, 35.2% and 86.4%, respectively, and the matched specificity were 78.4%, 96.1%, 90.2% and 58.8%, respectively. These highly expressed Streptococcus salivarius, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis in the saliva, alone or in combination, indicate their predictive value for ESCC.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), Predictive value, Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR), Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, Salivary bacteria

Abbreviations: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; HTS, high-throughput sequencing; OTUs, Operational Taxonomic Units; Q-PCR, quantitative PCR; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; ECA, esophageal carcinoma; KW, Kruskal-Wallis; LDA, linear discriminant analysis

Introduction

Esophageal carcinoma (ECA), especially esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), is a clinically serious disease with a high incidence in China; Chinese patients with ECA account for about 50% of global cases, and approximately 90% of global ESCC cases are in China.1 According to Global Cancer Statistics 2018, new cases and deaths of ECA are estimated to be about 572,000 and 509,000, respectively, making ECA the seventh most common cancers and sixth most common causes of death worldwide.2 The incidence of ECA often shows great variation, and is closely related to geography, ethnicity, and living habits.3 ECA cases exhibit obvious geographical distribution differences in China, with the incidence and mortality gradually increasing from South to East and from Northeast to Central China.4

Recently, the association between bacteria and tumorigenesis has been increasingly investigated. Several epidemiological studies from countries with a high incidence of ECA, such as India, Iran, and China, have indicated a potential association between poor oral hygiene and ESCC.5, 6, 7, 8 The dysbiosis of oral microbiota or the increase of pathogenic bacteria is often considered to be a common factor of poor oral hygiene.9 Moreover, studies have shown that Porphyromonas gingivalis infection is associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma.10 Since oral bacteria can be swallowed with saliva, the bacteria settled in the esophagus are thought to be more derived from the mouth. Previously, we have observed that the levels of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum are elevated in the tissues of ESCC, and P. gingivalis promotes proliferation of ESCC cells by activating NF-κB factor.11 Based on the above observations, we hypothesize the colonization of oral bacteria in the esophagus is associated with the occurrence of ESCC. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to investigate the association between oral microbiota and ESCC, and to explore the predictive value of salivary bacteria for the presence of ESCC.

Patients and methods

Subject selection

All patients with histologically diagnosed ESCC after upper endoscopy prior to any therapeutic procedures, such as surgery or chemoradiotherapy from January 2018 to December 2019 at Guangdong General Hospital were included in the study. Subjects with normal results for chest X-rays, gastroscopy, abdominal ultrasound, blood test and fecal occult-blood test, and digital rectal examinations at their annual physical check-up during the period of time were recruited as healthy controls. Patients and healthy subjects were randomly divided into screening and verification cohorts. Subjects with the following conditions were excluded: a) with concomitant other malignancies, or a history of operation, chemotherapy or radiotherapy for other malignancies; b) with a history of organic/systemic diseases, oral, archenteric, or hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus infection; c) with a history of severe diarrhea or administration of drugs that affect oral/salivary flora such as antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, hormones, intestinal probiotics, etc. within 4 weeks prior to saliva collection; and d) pregnancy or lactation.

The protocol of this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Guangdong General Hospital (Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences). Written informed consent was obtained from all the individuals.

Saliva collection

All subjects were asked to refrain from eating, cigarette smoking, alcohol intake to keep oral hygiene for at least 2 h before saliva collection, which was set at 8:00–11:00 am. Up to 5 mL of saliva from each individual was collected into a 50-mL centrifuge tube after gargling with 10 mL normal saline three times. The collected saliva samples were transported into a refrigerator within 30 min, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent use. All the procedures above were required to be completed within 2 h.

DNA extraction and storage

Saliva DNA was extracted by using UltraClean® Microbial DNA Isolation Kit purchased from QIAGEN in Germany. The DNA was subsequently stored at −20 °C in a refrigerator before utility. The purified DNA met the following quality criteria: the total mass ≥150 ng, DNA concentration ≥5 ng/μL, exhibiting obvious main band, free of degradation, and without contamination of DNA or protein.

Screening phase

16s RNA sequencing and data processing

Patients and healthy subjects allocated to the screening cohort were included in the screening phase.

Distinct V4 regions of 16S rRNA gene were amplified by a specific primer with a 12 bp barcode. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification with high-throughput sequencing was performed by thermocycling with 5 min initialization at 94 °C, 30 cycles (30 s) denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s annealing at 52 °C, and 30 s extension at 72 °C, followed by 10 min final elongation at 72 °C. PCR products were detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis (Guangzhou HaoMa Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Guangzhou, China) for the determination of fragment lengths and concentrations, and by GeneTools Analysis Software (Version4.03.05.0, SynGene) for comparative analysis of the product concentrations. The isodensity proportional mixed PCR products were purified with EZNA Gel Extraction Kit (Omega, USA), and eluted by TE buffer (REGAL, Shanghai, China) to recover the target DNA fragments. The DNA library was established following the standard procedures specified for NEBNextUltra™ DNA Library Prep Kit Illumina® (New England Biolabs, MA, USA). The DNA amplicon library was established by Illumina Hiseq2500 platform for PE250 sequencing, by Trimmomatic Software (V0.33, USADELLAB.org) for filtering Paired-end raw Reads, by Software FLASH (Fast Length Adjustment of SHort reads, V1.2.11,https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/FLASH/) for merging each PE Reads, and by Mothur Software (V1.35.1, http://www.mothur.org) for Raw Tags sequence quality filtering. Finally, all the clean tags (the effective sequences) were obtained.

Bioinformatics analysis

All clean tags were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) by using UPARSE Software (Version 10, http://www.drive5.com/usearch/) with a cutoff of 97% for identity. Those representative sequences of OTUs read with the highest frequencies were assigned at different taxonomic levels to annotate species, followed by a linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) tool with QIIME-based wrapper of the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier. LEfSe analysis was used to identify microbiomes of biomarker properties at multiple levels from salivary samples, with quantitative classification according to statistical significance, and to visualize the results using taxonomic bar charts and cladograms.

Verification phase

Patients and healthy subjects allocated to the verification cohort were included in the verification phase.

The expression levels of target bacteria were verified by quantitative PCR (Q-PCR). After specific primer sequences were designed according to selected target bacteria, the concentration of the positive recombinant plasmid was determined by an ultraviolet spectrophotometer. Then, the plasmid was diluted 10 times, and samples with concentrations of 10-2, 10-3, 10-4, 10-5, 10-6 and 10-7 were used to draw the standard curve. The reaction system was added with sterile water to 20 μL, involving SYBR Mix 10 μL, upstream and downstream primers 0.6 μL each, DNA template 1 μL. Reaction conditions involved one cycle of 30 s at 95 °C, one cycle of 5 s at 95 °C, and 40 cycles of 30 s at 60 °C, followed by DNA dilution of each sample at a concentration of 100 ng/μL used to detect DNA content of the sample. After each sample test was repeated 3 times and the average value was taken, the target bacterial expression, represented by the copy number, in the sample was calculated by the standard curve.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted based on detected saliva target bacteria expression in patients and healthy subjects, combined with indicators such as gender, age, cigarette smoking, alcohol intake and preference for hot food. The greater the AUC value the greater the predictive value of target bacteria for ESCC.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 22.0 Software (IBM, version 22.0) was used for statistical analysis, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare the differences in the relative abundance of bacteria, and independent sample t-test was used to detect the differences in age and bacterial copy quantity, and Chi-square test was used to detect the differences in sex, cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, hot food preference between ESCC patients and healthy subjects. In terms of LEfSe analysis, the two-tailed non-parametric factorial Kruskal-Wallis sum-rank test was first used to identify the bacterial species with significant differences in abundance between ESCC patients and healthy subjects, and then Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the differences between the two groups. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was used to achieve dimensionality reduction and assess the impact (LDA Score, with a filter value of 2) of species with significant differences. Finally, SPSS 22.0 Software was used to draw the ROC curve.

Results

Basic demographic characteristics of the enrolled subjects

A total of 178 patients with ESCC (90 cases in screening cohort, and 88 cases in verification cohort), and 101 healthy subjects (50 cases in screening cohort, and 51 cases in verification cohort) were eligible for the study. The average age of screening and verification sets in patients with ESCC was 61.7 and 61.4 years, respectively, and that of screening set in healthy subjects was 43.9 and 44.4 years, respectively. The demographic characteristics of the enrolled subjects are presented in Table S1.

Target bacteria identified in the screening phase

All clean tags (effective tags) were clustered by OTUs according to 97% sequence similarity, and the community composition of each sample was analyzed at phylum and genus levels.

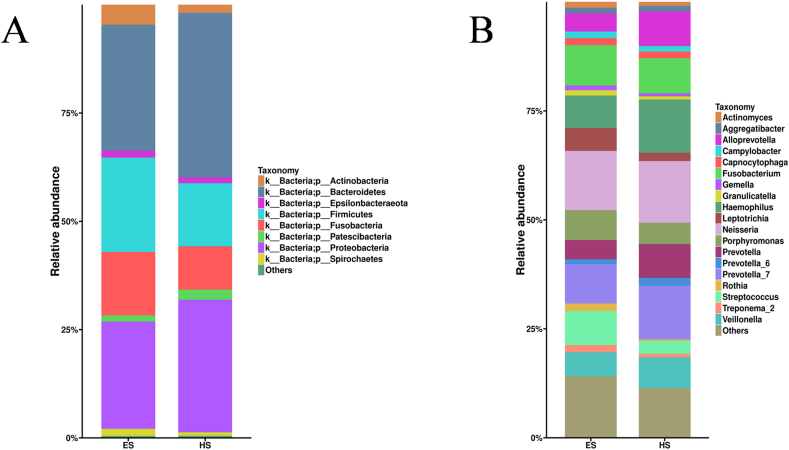

At the phylum level, the dominant bacteria, with a relative abundance of ≥1%, were Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Actinobacteria, Spirochaetes, Epsilonbacteraeota, and Patescibacteria in patients with ESCC and healthy subjects (Fig. 1A). Although there was little difference in species composition, the abundance ratio varied greatly between the two groups. Compared with healthy subjects, patients with ESCC showed an increased abundance of Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Actinobacteria, Spirochaetes and Epsilonbacteraeota, and decreased abundance of Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria and Patescibacteria (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

The relative abundance of dominant salivary bacteria at the phylum (A) and genus (B) levels in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ES) and healthy subjects (HS).

At the genus level, patients with ESCC showed mainly composed bacteria of Neisseria, Fusobacterium, Streptococcus, Hemophilus and Porphyromonas, and healthy subjects showed mainly composed species of Neisseria, Prevotella_7, Hemophilus, Fusobacterium and Alloprevotella. There were higher proportions of Fusobacterium, Streptococcus and Porphyromonas in patients with ESCC (9.3%, 7.8% and 6.9%, respectively) than in healthy subjects (8.1%, 4.9% and 3.0%, respectively). The histogram of the relative abundance of dominant bacteria ≥1% in the two groups is shown in Figure 1B.

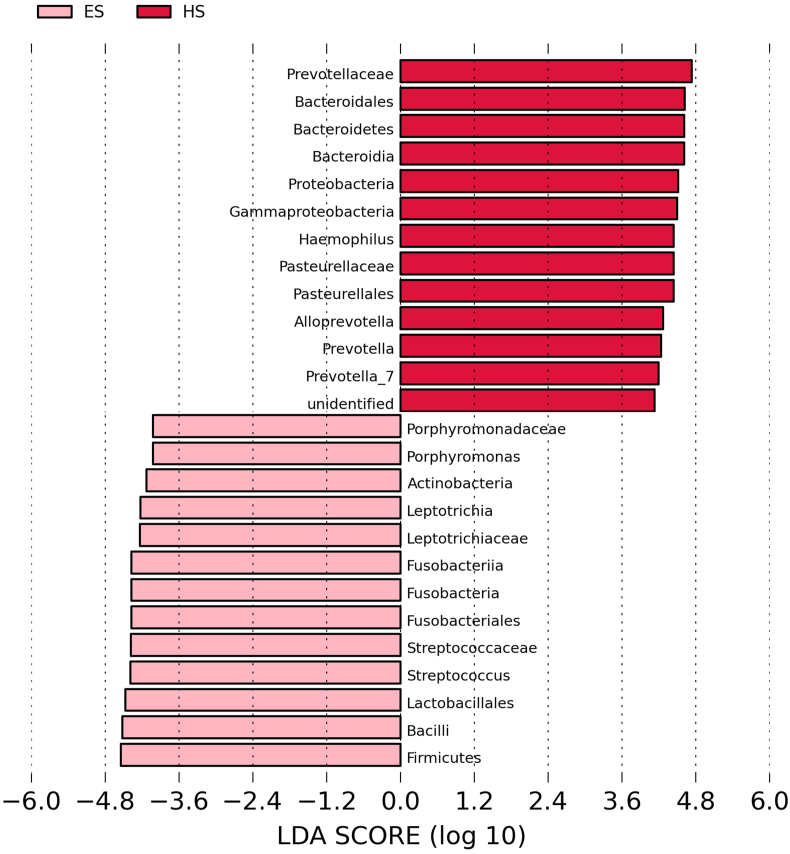

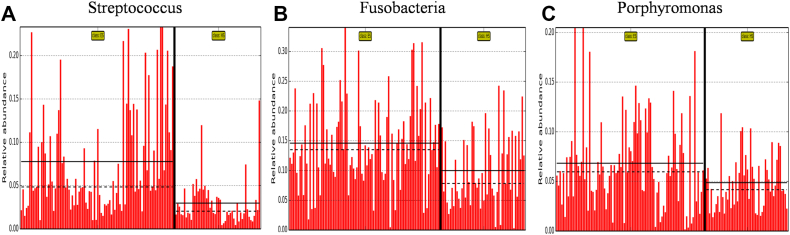

The histogram of LDA value distribution, which was obtained by LEfSe analysis and illustrates the species with significant enrichment in patients with ESCC and healthy subjects, is shown in Figure 2. Briefly, there were 28 bacteria with significant differences between the two groups; 14 including Streptococcus, Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, Firmicutes and Bacillus, etc. were more abundant in patients with ESCC, and 14 including Prevotellaceae, Bacteroidales, Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidia and Proteobacteria, etc. were more abundant in healthy subjects (all P < 0.05). The abundance comparison diagram of biomarkers (i.e. salivary bacteria of biomarker properties) in each sample of the two groups is shown in Figure 3. Compared with healthy subjects, the patients with ESCC had a dramatically increased abundance of Streptococcus, Fusobacterium and Porphyromonas (all P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Histogram of the Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores calculated for differentially abundant bacteria at the genus level between patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ES) and healthy subjects (HS).

Figure 3.

Biomarker (i.e. salivary bacteria of biomarker properties) images of Streptococcus (A), Fusobacteria (B) and Porphyromonas (C) at the genus level in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ES) and healthy subjects (HS).

Target bacteria confirmed in the verification phase

The design sequences of specific primers for Streptococcus salivarius, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis are shown in Table S2.

The correlation coefficients of these standard curves of S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis were 0.995, 0.990 and 0.998, respectively. The amplification curves of S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis showed well repeatability, and the single peak characteristics of standard melting curves of the three strains indicated the primer well specificity.

The average copies detected from salivary S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis in patients with ESCC and healthy subjects are shown in Table 1. According to the standard curves, the numbers of S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis in saliva samples in patients with ESCC were 9.00 × 105, 3.10 × 105 and 2.38 × 107, respectively, which were all significantly higher than that (4.85 × 104, 5.32 × 104 and 6.24 × 106, respectively) in healthy subjects (all P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Average copies of Streptococcus salivarius, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis detected from verification phase in the saliva of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and healthy subjects.

| Fungus name | ES group | HS group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| S.salivarius (mean ± SD) | 9.00 × 105±4.44 × 106 | 4.85 × 104±9.05 × 104 | 0.015 |

| F.nucleatum (mean ± SD) | 3.10 × 105±1.27 × 106 | 5.32 × 104±1.11 × 105 | 0.018 |

| P.gingivalis (mean ± SD) | 2.38 × 107±8.85 × 107 | 6.24 × 106±7.98 × 106 | 0.031 |

ES, patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; HS, healthy subjects; SD, standard deviation.

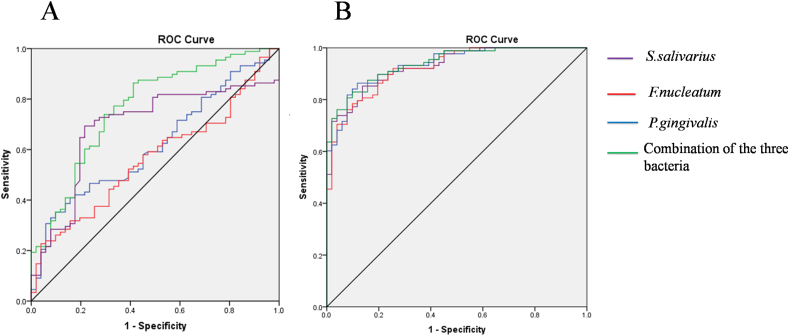

The ROC curves were plotted to verify the expression levels (i.e. copy numbers) of salivary S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis in the patients with ESCC and healthy subjects. The ROC curves of S. salivarius, F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis and the combination of the three bacteria for patients with ESCC are shown in Figure 4A. The AUCs of ROC curves were 69.0%, 56.5%, 61.8% and 76.4%, respectively. The sensitivities and specificities corresponding to the cutoff values were 69.3%, 22.7%, 35.2% and 86.4%, and 78.4%, 96.1%, 90.2% and 58.8%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of Streptococcus salivarius, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Porphyromonas gingivalis and the combination of the three bacteria alone (A) and incorporated with age, gender, cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and hot food preference (B) for predicting esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

When these factors (patient age, gender, cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and hot food) were incorporated in the analysis, the AUCs of ROC curves increased to 92.9%, 92.4%, 93.5%, and 93.9%, respectively, for S. salivarius, F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis and the combination of the three bacteria. The sensitivities and specificities corresponding to the cutoff values were 85.2%, 78.4%, 86.4% and 83.0%, and 86.3%, 90.2%, 88.2% and 90.2%, respectively (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated significantly increased S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis in the saliva of patients with ESCC, when compared with healthy subjects, indicating that these salivary bacteria are the major representative microbiota in oral cavity or salivary liquid of patients with ESCC. These findings also suggest that S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis in the saliva are associated with the development of ESCC, and may predict the presence of ESCC.

The pathogenesis of ESCC has not been fully elucidated. Moreover, accurate screening of patients with ESCC remains challenging as most patients are diagnosed in the advanced stage and lose the opportunity for curable therapy.1 Therefore, a simple and feasible screening method is urgently needed for the early diagnosis of ESCC. Saliva is the nutritional basis for the survival of oral bacteria, which can migrate into the esophagus with the swallowing of saliva, and thus, the flora of the esophageal mucosa is theoretically considered to be derived from the oral cavity. Furthermore, the present study, along with our previous study,11 clearly demonstrated that salivary bacteria, particularly the proportions of salivary Streptococcus, Fusobacterium and Porphyromonas are significantly increased in patients with ESCC. Additionally, the present study demonstrated that older age, male gender, smoking, alcohol intake and hot food preference were associated with ESCC, which confirms previous findings that these are the risk factors for the development and poor prognosis of ESCC.12, 13, 14

It has been reported that genes, proteins and small-molecules produced by oral/salivary bacteria are closely related to the occurrence of various cancers. Chemical carcinogens and/or inflammatory factors produced by oral/salivary bacteria, can form a complex and stable bacterial community and play an important pathogenic role in the development and progression of various local and systemic diseases.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 These oral/salivary bacteria-related diseases include, but are not limited to, oral squamous cell carcinoma,10,26 ESCC,11 inflammatory bowel disease,27 pancreatic cancer,28 celiac disease,29 and cardiovascular disease.30, 31, 32 In the present study, we further confirmed that salivary bacteria are associated with the development of ESCC, at the genus and species levels.

The genus Streptococcus is a bacterium that can locate on the oral mucosal surface, as well as the intestinal mucosa. It has been found that Streptococcus increases in oral squamous cell carcinoma tissues.33 Previous studies have found that Streptococcus and Streptococcus-reactive cytotoxic T cells are positively correlated with relapse-free survival after oral squamous cell carcinoma resection.26,33 However, the relationship between Streptococcus and ESCC has not been fully elucidated. Fusobacterium is involved in the occurrence of inflammatory diseases and may promote tumorigenicity by causing chronic inflammation.34,35 Fusobacterium is associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma, and Porphyromonas is the main pathogen of periodontitis, and closely related to the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma.10

F. nucleatum often colonizes in the mucosa of the oral cavity, vagina and gastrointestinal tract, and is reportedly to be a pathogen of periodontitis, chorioamnionitis and inflammatory bowel disease, and associated with colonic cancer and adenomas.36, 37, 38 Moreover, Yamamura et al39 demonstrated that the abundance of F. nucleatumin ESCC tissues was significantly higher than that in the normal esophageal mucosal tissues, and promoted tumor aggressive behavior by activating chemokines. P. gingivalis belongs to genus Porphyromonas, and is thought to be one of the pathogenic factors of periodontitis. Gao et al40 showed a significantly higher detection rate of P. gingivalis in ESCC tissues than in the adjacent normal tissues, and revealed positive associations of P. gingivalis with cell differentiation and metastasis of ESCC. Peters et al41 using 16S rRNA gene sequencing technology, observed abnormally increased oral P. gingivalis in the mouth wash samples, which was associated with lymph node metastasis and poor survival of patients with ESCC. Recent studies have shown that P. gingivalis42 and F. nucleatum43,44 promote oral squamous cell carcinoma and colorectal cancer by activating inflammatory NF-κB pathways. Similarly, P. gingivalis is found to promote proliferation and activity of ESCC cells by regulating NF-κB pathway in vitro.11

It has been reported that immunohistochemistry of serum thyroid transcription factor-1, pheochromoprotein A, CK5/6, CK18 and P63 yields detection rates of 53.7%, 72.8%, 17.7%, 94.9% and 100.0%, respectively, for ESCC.45 Recent studies have found an increased serum expression in exosome microRNA (i.e. miRNA-21) in ESCC.46 Serum POU3F3 may be a potential biomarker for ESCC diagnosis owing to its diagnostic sensitivity of 72.8% and specificity of 89.4%.47 As an indicator of monitoring health and disease, salivary bacteria have diagnostic advantages in screening many cancers.48 Using microarray technology, our previous study found that the expression of miRNA-10b, miRNA-144, and miRNA-451 in the whole saliva and miRNA-10b, miRNA-144, miRNA-21, and miRNA-451 in salivary supernatant were significantly up-regulated in patients with ESCC.49 The present study showed significantly increased expression of S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis in the saliva, indicating their predictive value for the presence of ESCC. Therefore, monitoring these salivary bacteria is expected to offer a novel, simple, noninvasive and promising screening approach for patients with ESCC.

Limitations

A few limitations exist in the present study. First, only salivary flora at genus level was sequenced by 16S rDNA sequencing in screening phase. Second, only representative species in each genus (i.e. S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis) were selected for Q-PCR quantification and ROC curve plotting, according to our previous studies.11 Therefore, this study is still at exploratory stage, and the conclusions need to be verified by future large-scale sample studies at molecular and genetic levels. Third, all recruited patients in the present study were confirmed with ESCC, so whether these 3 bacteria could be used for early diagnosis remains uncertain. Thus, an independent validation study is needed to confirm whether the changes in abundances of these 3 bacteria already occur in patients with precancerous lesions. Fourth, the present study mainly focused on the association between oral microbiota and ESCC and the predictive value of salivary bacteria for the presence of ESCC, but did not investigate the causes of changes in saliva microorganisms. It has been reported that the composition of salivary microbiota may be greatly affected by clinical, demographic and environmental factors including age, gender, dietary intake, smoking, and lifestyle habits.50 More extensive investigation is also required to confirm whether the observed microbial alteration is solely attributed to disease rather than other clinical and environmental factors. Fifth, to investigate the association between bacteria in saliva and esophageal cancer, the ideal design is to choose healthy subjects with young ages as the control group as their flora in saliva is closer to the normal status. Therefore, we chose younger people as the controls.

Conclusions

There is a significantly increased expression of S. salivarius, F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis in the saliva of patients with ESCC. These bacteria, alone or in combination, have a predictive value for the presence of ESCC. The predictive value can be further improved when age, gender, cigarette smoking, alcohol intake and hot food preference are taken into account.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scientific Research Project of Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China (No. 20184010458).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong General Hospital (Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences). All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from each of the patients or their immediate family member.

Data availability statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: Z.Li.

Performed the experiments: J.Wei, R.Li, Y.Lu.

Analyzed the data: J.Wei, R.Li, Y.Lu.

Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: Y.Lu, F.Meng, B.Xian, X.Lai, D.Yang.

H.Zhang, X.Lin, Y.Deng, L.Li, X.Ben, G.Qiao, W.Liu.

Wrote the paper: J.Wei, R.Li, Y.Lu, Z.Li.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating volunteers for their efforts and contributions.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2021.02.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Abnet C.C., Arnold M., Wei W.Q. Epidemiology of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):360–373. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman H.G., Xie S.H., Lagergren J. The epidemiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):390–405. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen W.Q., Zheng R.S., Zeng H.M. Report of cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2011. China cancer. 2015;24(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dar N.A., Islami F., Bhat G.A., et al. Poor oral hygiene and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Kashmir. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(5):1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guha N., Boffetta P., Wünsch Filho V., et al. Oral health and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and esophagus: results of two multicentric case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(10):1159–1173. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abnet C.C., Kamangar F., Islami F., et al. Tooth loss and lack of regular oral hygiene are associated with higher risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):3062–3068. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato F., Oze I., Kawakita D., et al. Inverse association between toothbrushing and upper aerodigestive tract cancer risk in a Japanese population. Head Neck. 2011;33(11):1628–1637. doi: 10.1002/hed.21649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wade W.G. The oral microbiome in health and disease. Pharmacol Res. 2013;69(1):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pushalkar S., Ji X., Li Y., et al. Comparison of oral microbiota in tumor and non-tumor tissues of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng F., Li R., Ma L., et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes the motility of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by activating NF-κB signaling pathway. Microbes Infect. 2019;21(7):296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCain R.S., McManus D.T., McQuaid S., et al. Alcohol intake, tobacco smoking, and esophageal adenocarcinoma survival: a molecular pathology epidemiology cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 2020;31(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01247-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin S., Xu G., Chen Z., et al. Tea drinking and the risk of esophageal cancer: focus on tea type and drinking temperature. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2020;29(5):382–387. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou X.N., Lu F.Z., Zhang S.W. Characteristics of esophageal cancer mortality in China, 1990–1992. Bull Chin Cancer. 2002;11(8):446–449. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nair J., Ohshima H., Nair U.J., Bartsch H. Endogenous formation of nitrosamines and oxidative DNA-damaging agents in tobacco users. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1996;26(2):149–161. doi: 10.3109/10408449609017928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salaspuro M.P. Acetaldehyde, microbes, and cancer of the digestive tract. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40(2):183–208. doi: 10.1080/713609333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karin M., Lawrence T., Nizet V. Innate immunity gone awry: linking microbial infections to chronic inflammation and cancer. Cell. 2006;124(4):823–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Socransky S.S., Haffajee A.D., Cugini M.A., Smith C., Kent R.L. Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(2):134–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pérez-Chaparro P.J., Gonçalves C., Figueiredo L.C., et al. Newly identified pathogens associated with periodontitis: a systematic review. J Dent Res. 2014;93(9):846–858. doi: 10.1177/0022034514542468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kholy K.E., Genco R.J., Van Dyke T.E. Oral infections and cardiovascular disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(6):315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathews M.J., Mathews E.H., Mathews G.E. Oral health and coronary heart disease. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0316-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeshita T., Kageyama S., Furuta M., et al. Bacterial diversity in saliva and oral health-related conditions: the Hisayama Study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22164. doi: 10.1038/srep22164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaura E., Brandt B.W., Prodan A., et al. On the ecosystemic network of saliva in healthy young adults. ISME J. 2017;11(5):1218–1231. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asakawa M., Takeshita T., Furuta M., et al. Tongue microbiota and oral health status in community-dwelling elderly adults. mSphere. 2018;3(4) doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00332-18. e00332-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kageyama S., Takeshita T., Furuta M., et al. Relationships of variations in the tongue microbiota and pneumonia mortality in nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(8):1097–1102. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mager D.L., Haffajee A.D., Devlin P.M., Norris C.M., Posner M.R., Goodson J.M. The salivary microbiota as a diagnostic indicator of oral cancer: a descriptive, non-randomized study of cancer-free and oral squamous cell carcinoma subjects. J Transl Med. 2005;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Said H.S., Suda W., Nakagome S., et al. Dysbiosis of salivary microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease and its association with oral immunological biomarkers. DNA Res. 2014;21(1):15–25. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrell J.J., Zhang L., Zhou H., et al. Variations of oral microbiota are associated with pancreatic diseases including pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2012;61(4):582–588. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francavilla R., Ercolini D., Piccolo M., et al. Salivary microbiota and metabolome associated with celiac disease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(11):3416–3425. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00362-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armingohar Z., Jørgensen J.J., Kristoffersen A.K., Abesha-Belay E., Olsen I. Bacteria and bacterial DNA in atherosclerotic plaque and aneurysmal wall biopsies from patients with and without periodontitis. J Oral Microbiol. 2014;6:23408. doi: 10.3402/jom.v6.23408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ford P.J., Gemmell E., Hamlet S.M., et al. Cross-reactivity of GroEL antibodies with human heat shock protein 60 and quantification of pathogens in atherosclerosis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2005;20(5):296–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2005.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ford P.J., Gemmell E., Chan A., et al. Inflammation, heat shock proteins and periodontal pathogens in atherosclerosis: an immunohistologic study. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21(4):206–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2006.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Sun F., Lin X., Li Z., Mao X., Jiang C. Cytotoxic T cell responses to Streptococcus are associated with improved prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Exp Cell Res. 2018;362(1):203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bashir A., Miskeen A.Y., Hazari Y.M., Asrafuzzaman S., Fazili K.M. Fusobacterium nucleatum, inflammation, and immunity: the fire within human gut. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(3):2805–2810. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4724-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lenzo J.C., O'Brien-Simpson N.M., Orth R.K., Mitchell H.L., Dashper S.G., Reynolds E.C. Porphyromonas gulae has virulence and immunological characteristics similar to those of the human periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2016;84(9):2575–2585. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01500-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakatsu G., Li X., Zhou H., et al. Gut mucosal microbiome across stages of colorectal carcinogenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8727. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allali I., Delgado S., Marron P.I., et al. Gut microbiome compositional and functional differences between tumor and non-tumor adjacent tissues from cohorts from the US and Spain. Gut Microbes. 2015;6(3):161–172. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1039223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salazar C.R., Sun J., Li Y., et al. Association between selected oral pathogens and gastric precancerous lesions. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e51604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamura K., Baba Y., Nakagawa S., et al. Human microbiome Fusobacterium nucleatum in esophageal cancer tissue is associated with prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(22):5574–5581. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao S., Li S., Ma Z., et al. Presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis in esophagus and its association with the clinicopathological characteristics and survival in patients with esophageal cancer. Infect Agent Cancer. 2016;11:3. doi: 10.1186/s13027-016-0049-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peters B.A., Wu J., Pei Z., et al. Oral microbiome composition reflects prospective risk for esophageal cancers. Cancer Res. 2017;77(23):6777–6787. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inaba H., Sugita H., Kuboniwa M., et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma through induction of proMMP9 and its activation. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16(1):131–145. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kostic A.D., Chun E., Robertson L., et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14(2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiDonato J.A., Mercurio F., Karin M. NF-κB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol Rev. 2012;246(1):379–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ling H., Chen X.Y., Chen Z.Z. Analysis of the value of combined detection of five tumor markers in the diagnosis of esophageal cancer. Chin J Prev Med. 2019;46(3):100–101. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cui Z., Xu J.M., Wang Y.L. Role of exosomes in diagnosisof digestive system cancers. World Chin J Dig. 2016;24(35):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong Y.S., Wang X.W., Zhou X.L., et al. Identification of the long non-coding RNA POU3F3 in plasma as a novel biomarker for diagnosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-14-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfaffe T., Cooper-White J., Beyerlein P., Kostner K., Punyadeera C. Diagnostic potential of saliva: current state and future applications. Clin Chem. 2011;57(5):675–687. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.153767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xie Z., Chen G., Zhang X., et al. Salivary microRNAs as promising biomarkers for detection of esophageal cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e57502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao X., Lim F. Lifestyle risk factors in esophageal cancer: an integrative review. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2020;43(1):86–98. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.