Abstract

The binding of cellobiohydrolases to cellulose is a crucial initial step in cellulose hydrolysis. In the search for a detailed understanding of the function of cellobiohydrolases, much information concerning how the enzymes and their constituent catalytic and cellulose-binding domains interact with cellulose and with each other and how binding changes during hydrolysis is still needed. In this study we used tritium labeling by reductive methylation to monitor binding of the two Trichoderma reesei cellobiohydrolases, Cel6A and Cel7A (formerly CBHII and CBHI), and their catalytic domains. Measuring hydrolysis by high-performance liquid chromatography and measuring binding by scintillation counting allowed us to correlate activity and binding as a function of the extent of degradation. These experiments showed that the density of bound protein increased with both Cel6A and Cel7A as hydrolysis proceeded, in such a way that the adsorption points moved off the initial binding isotherms. We also compared the affinities of the cellulose-binding domains and the catalytic domains to the affinities of the intact proteins and found that in each case the affinity of the enzyme was determined by the linkage between the catalytic and cellulose-binding domains. Desorption of Cel6A by dilution of the sample showed hysteresis (60 to 70% reversible); in contrast, desorption of Cel7A did not show hysteresis and was more than 90% reversible. These findings showed that the two enzymes differ with respect to the reversibility of binding.

The cellulolytic enzyme system of Trichoderma reesei can efficiently degrade crystalline cellulose to glucose. The enzymes that hydrolyze the cellulose component can be divided into the following two types: endoglucanases (EC 3.2.1.4), which hydrolyze internal bonds in the cellulose chains; and cellobiohydrolases (exoglucanases; EC 3.2.1.91), which hydrolyze from the chain ends and produce predominantly cellobiose (for a review see reference 24). The two cellobiohydrolases secreted by T. reesei appear to be complementary in some respects. They exhibit synergy and have been shown to act at different ends of the cellulose chain; Cel7A acts at the reducing end, and Cel6A acts at the nonreducing end (1) (in this paper the nomenclature of Henrissat et al. [7] is used; Cel7A is the same as CBHI, and Cel6A is the same as CBHII). There are data that describe the molecular mechanisms of hydrolysis; these data were obtained by using X-ray structures together with substrates and inhibitors and by using different cellulase mutants. There are also structural data for the special tunnel-shaped active sites of Cel7A and Cel6A that are involved in a range of different interactions (4, 5, 8, 18, 21). A special feature that is found in Cel7A and Cel6A and is also observed in many other cellulases is the modular structure of the enzymes; the enzymes have a cellulose-binding domain (CBD) and a catalytic domain (CD), which are connected by a linker region. Three-dimensional structures of CBDs are available, and molecular details of the interactions have been characterized extensively (9, 10, 13). Experiments have shown that the interaction between the domains is not simple but involves several factors, such as the properties of the linking region, which affect the function (17, 19). Many molecular details are available, but one of the main unanswered questions concerning the function of the enzymes is related to how the two domains work together and how they interact with cellulose during initiation of hydrolysis as well as in the processive movement along cellulose chains.

Binding is an important prerequisite for hydrolysis and has been the focus of numerous studies. However, very little is known about the dynamics of binding during hydrolysis. Since hydrolysis itself changes the substrate, it can be expected that the fraction of bound protein also changes during hydrolysis. Cellobiohydrolases Cel7A and Cel6A of T. reesei present another question. We recently demonstrated that there is a qualitative difference between these enzymes (3). The desorption properties of the CBDs of Cel7A and Cel6A are different; the CBD of Cel6A does not desorb from cellulose nearly as well as the CBD of Cel7A does.

In this study we used in vitro radiolabeling with tritium to monitor the partitioning of T. reesei Cel7A and Cel6A between solid and liquid phases during hydrolysis and to study how the CD and the CBD contribute to the binding of the whole enzyme. We also studied the dynamics of desorption and how the end product cellobiose affects binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzymes and substrates.

T. reesei Cel7A and Cel6A were purified as described previously (16), and their CDs were purified as described by Suurnäkki et al. (22). The concentrations of protein stock solutions were determined by UV adsorption at 280 nm by using the following molar extinction coefficients: Cel7A, 83 000 M−1 cm−1; Cel6A, 104 000 M−1 cm−1; Cel7A CD, 80 000 M−1 cm−1; and Cel6A CD, 86 000 M−1 cm−1 (7a). Bacterial microcrystalline cellulose (BMCC) from Acetobacter xylinum was prepared as described previously (6, 8) from “Nata de Coco.”

Labeling of Cel6A and Cel7A and their CDs with 3H.

Intact enzymes and CDs were labeled with 3H by reductive methylation essentially as described by Tack et al. (23), and 3H-labeled CBDs were prepared as described by Carrard and Linder (3) and Linder and Teeri (12). The proteins were concentrated, and the buffer was exchanged with 200 mM HEPES (pH 8.5). Tritium-enriched NaBH4 (3.6 μmol; 50 mCi; catalog no. TRK45; Amersham) dissolved in the same buffer and 40 μl of 3.7% formaldehyde were added to each protein sample. The total reaction volume was 2 ml, and the protein concentration was 2.5 to 3.5 g liter−1. The mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min, and the unbound radioactive material was removed by gel filtration performed with disposable columns (10 DG Econo Pac; Bio-Rad) equilibrated with 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.0). The UV adsorption at 280 nm and the radioactivity in each fraction were determined. The same procedure was used to label both Cel6A and Cel7A, as well as their CDs.

The purity of the sample and the fraction of unbound label were determined by ion-exchange chromatography performed with a Mono Q (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) ion-exchange column and 20 mM triethanolamine (pH 7.6); the column was eluted with an NaCl gradient. The radioactivity in each fraction was measured, and the amount of free label was determined. The fraction of unbound label in each purified sample was also determined by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation performed with a 30% TCA solution and sodium deoxycholate (15).

Measurement of enzyme activity and substrate hydrolysis.

The enzymatic activities of labeled and unlabeled Cel7A were determined by using a small fluorogenic substrate, 0.5 mM methylumbelliferyl cellobioside (MUG2), as described previously (25). Each sample was incubated in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at 50°C for 10 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 M Na2CO3, and the fluorescence emission at 446 nm (after excitation at 365 nm) was measured. The activities of Cel7A and Cel6A with BMCC before and after labeling were determined by hydrolysis experiments; solubilized cellobiose and glucose contents were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography as described below.

The hydrolysis experiments were conducted in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at 30°C for Cel6A and at 40°C for Cel7A. A temperature of 30°C was used for Cel6A since this enzyme might be inactivated by prolonged incubation at 40°C. The substrate concentrations were the same as those used in the binding experiments (1 g liter−1). The sample incubation times ranged from 20 min to 69 h, and the reactions were terminated by filtering the samples (0.22-μm-pore-size Durapore GV13 filter; Millipore). The amounts of cellobiose and glucose in the hydrolysates were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography by using refractive index detection and a Shodex type Ca-440 6040 column at 80°C. Water was used as the mobile phase, and the flow rate was 0.6 ml min−1. The degree of hydrolysis in each experiment was calculated by subtracting the amount of cellobiose and glucose liberated from the theoretical amount of glucose in the initial cellulose preparation.

Binding measurements.

All binding experiments were performed in a thermostat-controlled environment. The buffer used was 25 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin to prevent nonspecific adsorption. The initial enzyme concentrations ranged from 20 nM to 2 μM. Equal volumes (100 to 150 μl) of enzyme and BMCC in aqueous suspensions (2 g liter−1) were mixed in a glass tube with a magnetic stirrer. After 30 min of incubation, samples were filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size Millex GV13 filter (Millipore). The amount of 3H in the filtrate was quantified by liquid scintillation counting. The amount of bound enzyme was calculated from the difference between the initial and final free enzyme concentrations.

The reversibility of binding was determined by dilution experiments. A series of identical reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min in order to obtain equilibrium (4 and 22°C). Subsequently, the mixtures were diluted 10-fold with the same buffer as the buffer in the sample. After incubation for different times, the mixtures were filtered as described above, and the amounts of released protein were calculated. The effect of cellobiose on adsorption was examined by incubating samples in acetate buffer containing different amounts of cellobiose (0.02 to 16 mM). The initial enzyme concentration was 200 nM for all of the proteins except Cel6A CD; the initial concentration of Cel6A CD was 700 nm because of its lower affinity.

RESULTS

Labeling of proteins.

Tritium-containing methyl groups are introduced into the free amines during labeling. Scintillation counting of the fractions collected from the analytical ion-exchange chromatography preparation showed that more than 99.6% of the total radioactivity was associated with a single protein peak for all preparations. The amounts of unbound radioactivity measured by TCA precipitation were slightly higher (less than 2%), probably because TCA did not efficiently precipitate small amounts of protein. The measured specific activities of the tritium-labeled enzymes were 7.7 Ci, 6.6, 8.3, and 6.1 Ci mmol−1 for Cel7A, Cel6A, Cel7A CD, and Cel6A CD, respectively. This gave a practical detection limit of 5 to 10 nM. The 95% confidence interval for the quantification procedure, including pipetting, was ±2%.

Reductive methylation did not affect the enzymatic activity. All of the activity of Cel7A against MUG2 was present after labeling (13.8 ± 0.5 nkat mg−1 before labeling and 13.1 ± 1 nkat mg−1 after labeling). Cel6A is not active against MUG2. The effects of methylation on the hydrolytic activities of the enzymes were also checked by performing a BMCC hydrolysis analysis. Methylated and nonmethylated proteins had identical enzymatic activities during incubation for 50 h.

Binding studies.

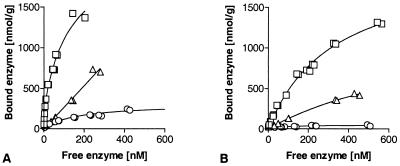

The binding isotherms of Cel7A and Cel6A, as well as their CDs and CBDs, are shown in Fig. 1. The effects of binding saturation and cellulose hydrolysis on binding behavior were avoided by using low protein concentrations. At low concentrations, the amount of bound enzyme was linearly dependent on the free enzyme concentration. Nonspecific adsorption did not affect the binding points at free concentrations greater than 200 nM, as shown by identical binding with and without bovine serum albumin. The partition coefficients were calculated from the initial slopes of the measured isotherms at different temperatures (Table 1). The partition coefficients were clearly temperature dependent for both enzymes and their isolated domains, and better binding occurred at low temperatures.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the binding affinities of intact proteins and their modular components. Isotherms were determined at 4°C. (A) Cel7A. (B) Cel6A. Symbols: □, intact enzyme; ▵, CBD; ○, CD.

TABLE 1.

Temperature dependence of the partition coefficients of Cel6A and Cel7A and their separate domains

| Enzyme or domain | Partition coefficient (liters g−1) at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4°C | 22°C | 40°C | |

| Cel7A | 43 ± 2 | 18 ± 2 | 10 ± 1 |

| Cel7A CBD | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | NDa |

| Cel7A CD | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | ND |

| Cel6A | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

| Cel6A CBD | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | ND |

| Cel6A CD | ∼0.2 | ∼0.1 | ND |

ND, not determined.

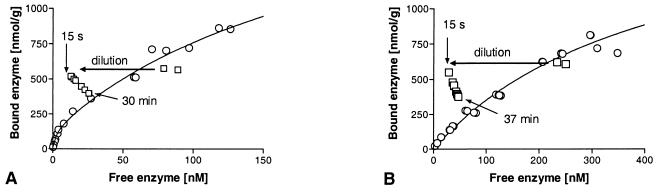

The desorption experiment data for Cel7A showed that after dilution with buffer, a new equilibrium was established on the same isotherm (i.e., desorption did not exhibit hysteresis) (Fig. 2A). The new equilibrium was established within 30 min at both 4 and 22°C. The desorption of Cel6A consistently exhibited hysteresis, and thus, the enzyme was only partially reversibly bound, as shown in Fig. 2B. We calculated the reversibility by comparing the amount bound after dilution if no desorption occurred, which was the same as extrapolating to the amount bound at time zero after dilution, with the point on the isotherm corresponding to complete reversibility. This is a general way of calculating reversibility but is not strictly comparable to calculations based on data from experiments in which desorption is brought about by exchange of buffer (as described by Bothwell et al. [2]) instead of dilution.

FIG. 2.

Reversibility of Cel7A (A) and Cel6A (B) by dilution with buffer at 22°C. When a sample was diluted, the reversible Cel7A returned to a point on the isotherm, whereas Cel6A exhibited hysteresis and did not completely return to the isotherm. Similar results were obtained at 4°C.

We found that adding cellobiose affected binding of the CDs of both Cel7A and Cel6A even at concentrations less than 1 mM. In the presence of 1.5 mM cellobiose, the amount of bound Cel7A CD increased almost twofold and the amount of bound Cel6A CD increased fivefold. By contrast, the binding of whole Cel6A decreased slightly in the presence of 1.6 mM cellobiose, whereas the affinity of Cel7A to cellulose was essentially unaffected.

Hydrolysis.

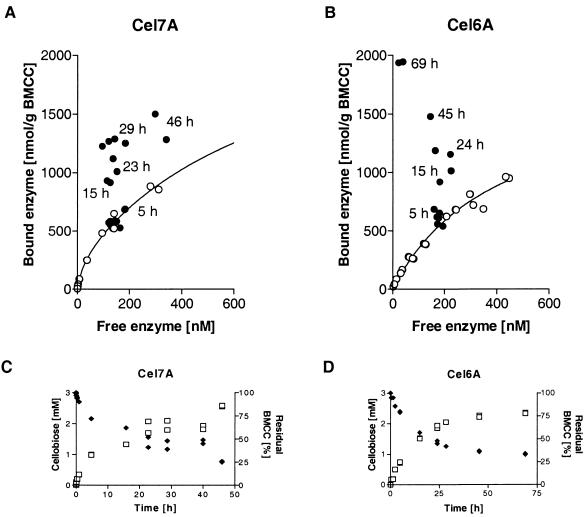

In order to monitor the binding of enzyme during hydrolysis, bound Cel7A and Cel6A were quantified by using the hydrolysis samples. After 48 h of incubation at 40°C (Cel7A) or at 30°C (Cel6A), approximately 75% conversion was observed (Fig. 3C and D). The initial enzyme concentration was approximately 0.8 μM. The data obtained showed that binding of both Cel7A and Cel6A to residual substrate clearly increased during hydrolysis (Fig. 3A and B). The amount of bound Cel7A was constant during the first 4 to 5 h of hydrolysis, but later the enzyme bound better to the residual BMCC. The amount of free enzyme during the experiment was practically constant. In the case of Cel6A, the increase in binding to the residual cellulose was even more marked. In the last stage of hydrolysis, the fraction of free enzyme was only 15% of the initial free enzyme concentration. This resulted in a very high ratio of bound enzyme to residual substrate.

FIG. 3.

(A and B) Binding isotherms for Cel7A and Cel6A (○) and the adsorbed proteins at different stages of hydrolysis (●). (C and D) Course of hydrolysis, plotted as the amount of cellobiose produced (□) and the amount of residual cellulose (⧫). The data show that more enzyme per unit of cellulose was bound as hydrolysis proceeded.

DISCUSSION

Studying the progress of hydrolysis of cellulose by cellobiohydrolases requires that a number of parameters be considered. In this study we focused on different aspects of binding from a dynamic point of view. An understanding of the connection between binding and hydrolysis is crucial but has proved to be very elusive. In this study we first evaluated the suitability of tritium labeling by reductive methylation of Cel6A and Cel7A in order to monitor binding. We have shown previously that CBDs can be successfully labeled in this way (12). Here we found that both the CD and the intact protein of both cellobiohydrolases were labeled, which made it possible to compare the relative affinities of the two enzymes and also to monitor reversibility and partitioning during cellulose degradation.

The two-domain structure is rather widespread in cellulases and hemicellulases. As we previously suspected (11, 19), the linkage between the CD and the CBD results in increased overall binding of the intact enzyme. Figure 1 shows a comparison of the two domains and the intact enzymes for both Cel7A and Cel6A. In both cases the trend is clear; the intact enzyme exhibited significantly higher affinity than either domain alone. Interestingly, this property was most pronounced at the low concentrations used in this study. If very high protein concentrations are used, then the high capacity of the CBD gives the impression that CBD binding is dominant over the binding of the intact enzyme and the CD (20).

Surprisingly, recent results (3) have shown that there is a significant functional difference between the Cel6A and Cel7A CBDs. Whereas the Cel7A CBD can be eluted easily from cellulose simply by diluting the preparation with buffer, this is not the case for the Cel6A CBD. Instead, the process exhibits a clear hysteresis effect when the “ascending” isotherm obtained by adsorption is compared to the “descending” isotherm obtained by dilution. The reversible behavior also applies to whole Cel7A, as noted in this study and elsewhere (2). However, we found that Cel6A does exhibit hysteresis, but not to the same extent as its CBD. One possibility is that this finding is related to the fact that binding of the enzyme is determined by the cooperative effects of the two domains; thus, the enzyme does not rely on CBD-dominated binding. We also investigated the reversibility of binding of the CDs, but due to the low overall affinity and consequently relatively large error limits, it was difficult to draw any conclusions.

The cellulose substrate obviously changes during hydrolysis. The reduction in particle size during hydrolysis should also increase the surface/mass ratio. Because changes were anticipated, we monitored the amount of bound enzyme as a function of the extent of hydrolysis. In a reversible system with a homogeneous substrate, when the amount of bound enzyme is plotted as a function of the amount of free enzyme, the points should move up along the isotherm as hydrolysis proceeds, since the amount of cellulose decreases and, consequently, the amount of free enzyme increases; that is, both the amount of bound enzyme and the amount of free enzyme plotted on an isotherm graph should increase. The important point is to relate the increase to the points on the isotherm. The expected increase in the amount of bound enzyme has been reported previously (14), but the important relationship to binding isotherms was not described. Furthermore, because filter paper was used as a substrate in the previous study, a significant mass transfer-pore diffusion effect could be expected; such an effect is unlikely when the much more accessible substrate BMCC is used, as in this study. Figure 3 shows that the concentration of free enzyme was more or less constant and that the amount of bound enzyme per unit of residual cellulose weight increased. Interestingly, the departure from the isotherm occurred after 5 h, when 25% of the substrate had already been hydrolyzed. The reason for the observed effect is not easy to pinpoint. In the case of Cel7A, it has been established that the binding is close to 100% reversible, and the 30 to 40% irreversibility that Cel6A exhibits does not seem to be sufficient to account for the effect. We also observed that the same increase in binding occurred with the CDs.

It has been noted previously that very high cellobiose concentrations cause an increase in binding of Cel7A CD (but not of intact enzyme or CBD) (20). Therefore, in principle, increased binding could be due to an increased amount of cellobiose. In this work, we studied the effect of cellobiose on the binding of Cel6A, as well as the binding of Cel7A (and the CDs), at concentrations present at the end of the hydrolysis experiments (2.5 to 3 mM). The effect on the Cel6A CD was more pronounced than the effect on the Cel7A CD. It is surprising that whole Cel6A exhibited a behavior opposite the behavior of its CD and that Cel7A was not affected, although its CD was clearly affected. Nevertheless, it appears that increased cellobiose concentrations did not result in increased binding during the hydrolysis experiments.

Binding of cellulases is an important and difficult problem which has been the focus of numerous studies. We have demonstrated the underlying mechanisms of processes, such as the binding of two relatively low-affinity domains which combine to produce an intact enzyme with a much higher affinity, thus clarifying the role of the CBD. The question of reversibility is still puzzling and will probably require further mutagenesis of both domains and the linker in order to be resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Koivula, T. Teeri, and R. Fagerström for reading the manuscript and M. Bailey for linguistic revision. G. Carrard is thanked for providing labeled CBDs.

M.L. acknowledges financial support provided by the Academy of Finland. H.P. acknowledges support provided by the Nordic Energy Research Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barr B K, Hsieh Y L, Ganem B, Wilson D B. Identification of two functionally different classes of exocellulases. Biochemistry. 1996;35:586–592. doi: 10.1021/bi9520388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bothwell M K, Wilson D B, Irwin D C, Walker L P. Binding reversibility and surface exchange of Thermomonospora fusca E3 and E5 and Trichoderma reesei CBHI. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1997;20:411–417. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrard G, Linder M. Widely different off-rates of two closely related cellulose-binding domains from Trichoderma reesei. Eur J Biochem. 1999;262:637–643. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Divne C, Ståhlberg J, Reinikainen T, Ruohonen L, Pettersson G, Knowles J K, Teeri T T, Jones T A. The three-dimensional crystal structure of the catalytic core of cellobiohydrolase I from Trichoderma reesei. Science. 1994;265:524–528. doi: 10.1126/science.8036495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Divne C, Ståhlberg J, Teeri T T, Jones T A. High-resolution crystal structures reveal how a cellulose chain is bound in the 50 A long tunnel of cellobiohydrolase I from Trichoderma reesei. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:309–325. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilkes N R, Jervist E, Henrissat B, Tekant B, Miller R C, Warren R A J, Kilburn D G. The adsorption of bacterial cellulase and its two isolated domains to crystalline cellulose. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6743–6749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henrissat B, Teeri T T, Warren R A. A scheme for designating enzymes that hydrolyse the polysaccharides in the cell walls of plants. FEBS Lett. 1998;425:352–354. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Koivula, A. Personal communication.

- 8.Koivula A, Kinnari T, Harjunpaa V, Ruohonen L, Teleman A, Drakenberg T, Rouvinen J, Jones T A, Teeri T T. Tryptophan 272: an essential determinant of crystalline cellulose degradation by Trichoderma reesei cellobiohydrolase Cel6A. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:341–346. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraulis J, Clore G M, Nilges M, Jones T A, Pettersson G, Knowles J, Gronenborn A M. Determination of the three-dimensional solution structure of the C-terminal domain of cellobiohydrolase I from Trichoderma reesei. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7241–7257. doi: 10.1021/bi00444a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linder M, Mattinen M-L, Kontteli M, Lindeberg G, Ståhlberg J, Drakenberg T, Reinikainen T, Pettersson G, Annila A. Identification of functionally important amino acids in the cellulose-binding domain of Trichoderma reesei cellobiohydrolase I. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1056–1064. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linder M, Salovuori I, Ruohonen L, Teeri T T. Characterization of a double cellulose-binding domain. Synergistic high affinity binding to crystalline cellulose. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21268–21272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linder M, Teeri T T. The cellulose-binding domain of the major cellobiohydrolase of Trichoderma reesei exhibits true reversibility and a high exchange rate on crystalline cellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12251–12255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattinen M L, Kontteli M, Kerovuo J, Linder M, Annila A, Lindeberg G, Reinikainen T, Drakenberg T. Three-dimensional structures of three engineered cellulose-binding domains of cellobiohydrolase I from Trichoderma reesei. Protein Sci. 1997;6:294–303. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nidetzky B, Claeyssens M. Specific quantification of Trichoderma reesei cellulases in reconstituted mixtures and its application to cellulase-cellulose binding studies. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;44:961–966. doi: 10.1002/bit.260440812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozols J. Amino acid analysis. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:587–601. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahkamo L, Siika-aho M, Vehviläinen M, Dolk M, Viikari L, Nousiainen P, Buchert J. Modification of hardwood dissolving pulp with purified Trichoderma reesei cellulases. Cellulose. 1996;3:153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinikainen T, Teleman O, Teeri T T. Effects of pH and high ionic strength on the adsorption and activity of native and mutated cellobiohydrolase I from Trichoderma reesei. Proteins. 1995;22:392–403. doi: 10.1002/prot.340220409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rouvinen J, Bergfors T, Teeri T, Knowles J K, Jones T A. Three-dimensional structure of cellobiohydrolase II from Trichoderma reesei. Science. 1990;249:380–386. doi: 10.1126/science.2377893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srisodsuk M, Reinikainen T, Penttila M, Teeri T T. Role of the interdomain linker peptide of Trichoderma reesei cellobiohydrolase I in its interaction with crystalline cellulose. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20756–20761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ståhlberg J, Johansson G, Pettersson G. A new model for enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose based on the two-domain structure of cellobiohydrolase I. Biot/Technology. 1991;9:286–290. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ståhlberg J, Divne C, Koivula A, Piens K, Claeyssens M, Teeri T T, Jones T A. Activity studies and crystal structures of catalytically deficient mutants of cellobiohydrolase I from Trichoderma reesei. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:337–349. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suurnäkki, A., M. Tenkanen, M.-L. Niku-Paavola, L. Viikari, M. Siika-aho, and J. Buchert. Trichoderma reesei cellulases and their core domains in hydrolysis and modification of chemical pulp. Submitted for publication.

- 23.Tack B F, Dean J, Eilat D, Lorenz P E, Schechter A N. Tritium labeling of proteins to high specific radioactivity by reductive methylation. J Biol Chem. 1980;18:8842–8847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teeri T T. Crystalline cellulose degradation: new insights into the function of cellobiohydrolases. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:160–167. [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Tilbeurgh H, Clayssens M, de Bruyne C. The use of 4-methylumbelliferyl and other chromophoric glycosides in the study of cellulolytic enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1982;149:152–156. [Google Scholar]