Abstract

Pegivirus (family Flaviviridae) is a genus of small enveloped RNA viruses that mainly causes blood infections in various mammals including human. Herein, we carried out an extensive survey of pegiviruses from a wide range of wild animals mainly sampled in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China. Three novel pegiviruses, namely Passer montanus pegivirus, Leucosticte brandti pegivirus and Montifringilla taczanowskii pegivirus, were identified from different wild birds, and one new rodent pegivirus, namely Phaiomys leucurus pegivirus, was identified from Blyth's vole. Interestingly, the pegiviruses of non-mammalian origin discovered in this study substantially broaden the host range of Pegivirus to avian species. Co-evolutionary analysis showed virus-host co-divergence over long evolutionary timescales, and indicated that pegiviruses largely followed a virus-host co-divergence relationship. Overall, this work extends the biodiversity of the Pegivirus genus to those infecting wild birds and hence revises the host range and evolutionary history of genus Pegivirus.

Keywords: Bird, Rat, Pegivirus, Evolution, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

Highlights

-

•

Novel pegiviruses were identified from wild-life animals in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.

-

•

The three divergent species of bird pegiviruses substantially broaden the host range of Pegivirus.

-

•

A long-term evolutionary relationship was established between pegiviruses and their vertebrate hosts.

1. Introduction

Genus Pegivirus (family Flaviviridae) comprises enveloped positive sense single-stranded RNA viruses ranging from 8.9 to 11.3 kb encoding a single polyprotein (Simmonds et al., 2017). When co- and post-translationally cleaved by proteases, pegivirus polyprotein generates several proteins: 5′-Envelope 1 (E1)-E2-protein X (Px)-Nonstructural 2 (NS2)-NS3-NS4A-NS4B-NS5A-NS5B-3′ (Simmonds et al., 2017). Within genus Pegivirus, 11 species have been described so far (Pegivirus A–K), such as theiler's disease-associated virus, human hepegivirus, and hepatitis GB virus A. Most of the currently identified pegiviruses infecting humans and other mammalian hosts, including non-human primates (New World monkeys, Old World monkeys and chimpanzees), bats, horses, pigs, and rodents (Schaluder et al., 1995; Sibley et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2020). Recently, novel pegiviruses have been reported from dolphin species, the common marmoset, and the vervet monkey (Rodrigues et al., 2019; Porter et al., 2020). On the other hand, the report of pegiviruses in non-mammalian host has been scarce. The only non-mammalian member of pegivirus identified so far is goose pegivirus (GPgV), which was identified in several goose farms exhibiting high lymphotropism in Sichuan Province and the Chongqing municipality of China, and formed a sister clade to mammalian pegiviruses (Wu et al., 2020). Until now, there are only two rodent pegiviruses so far, which have been identified in serum samples from Neotoma albigula (rodent pegivirus isolate cc61) and Rattus norvegicus (norway rat pegivirus isolate NrPgV/NYC-E13), respectively, all belonging to species Pegivirus J (Kapoor et al., 2013; Firth et al., 2014).

Studies have shown that birds are important natural reservoirs or amplifying hosts for many emerging or re-emerging viral pathogens, such as influenza A virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and West nile virus (Valiakos et al., 2019; Ramey and Reeves, 2020; Hameed et al., 2021). Similarly, rodents, which constitute the most diverse mammal order Rodentia and represents about 40% of all mammal species (Burgin et al., 2018), are also natural reservoirs of diverse zoonotic viruses (Wu et al., 2021) such as arenaviruses and hantaviruses (Manigold and Vial, 2014; Han et al., 2015). A thorough understanding of viruses harbored by birds and rodent species is of great importance to the prevention of emerging or re-emerging zoonotic pathogens in the future.

Currently, the knowledge about the viral diversity in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China, especially potential zoonotic viruses, is still very limited. Furthermore, pegiviruses in wild animals from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau has not been reported. Therefore, in this work, we identified four new pegiviruses from respiratory tract samples of birds and voles, mainly sampled from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China, which shed new lights on the diversity and evolution of this important genus.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection and ethical considerations

In April 2018, 41 rodents including 32 rats (Phaiomys leucurus), and 31 wild birds (Leucosticte brandti) were trapped in Cona County of Tibet, China. Furthermore, 23 wild birds (16 Montifringilla taczanowskii and 7 Pseudopodoces humilis) from Yushu City of Qinghai Province and 13 wild birds (Passer montanus) from Zhaoping County of Guangxi Province were trapped in July 2019 and in October 2020, respectively. All the sampled wildlife had no obvious diseases. All animals were humanely euthanized, and their respiratory tracts were collected for analysis. Each respiratory tract sample was placed in Hank's balanced salt solution and was temporarily stored in −20 °C refrigerators of local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) before transporting to our laboratory in Beijing and subsequent storage at −80 °C. The specimens were identified to species by professionals through morphological observation or the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. All sampling work was carried out by the local CDC as part of surveillance programs and was authorized by the State Key Laboratory for Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control.

2.2. RNA extraction and unbiased deep-sequencing

A total of 30 mg of tissue was excised from each sample, washed three times using Hank's balanced salt solution, homogenized in PBS using the TissueLyser II system, and was then extracted and purified by the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN, cat no: 74134, Düsseldorf, Germany). The obtained total RNA was mixed in equal proportions into four pools according to the animal type and sampling site. The four libraries were conducted as previously (Zhu et al., 2021a, 2021c). In brief, total RNA were subjected to rRNA extraction using the Ribo-Zero Gold rRNA Removal Kit (Illumina, cat no: MRZE706, San Diego, USA), and were then constructed using the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Gold kit (Illumina, cat no: RS-122-2201, San Diego, USA) and sequenced by the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform (Zhu et al., 2021b).

2.3. Viral discovery

The meta-transcriptomic pipeline was conducted according to previous reports (Shi et al., 2018; Porter et al., 2020). Raw data were trimmed to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences using Trimmomatic v0.39 (Bolger et al., 2014). The resulting high-quality data were subsequently used for de novo assembly by Trinity v2.6.4 default parameter settings (Grabherr et al., 2011). The assembled contigs were screened against the non-redundant protein databases of NCBI with an e-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5 using Diamond (Buchfink et al., 2015). To confirm the obtained viral contigs, reads were mapped back to the corresponding viral contigs and assembly was conducted once more. The number of reads mapped back to pegivirus genome divided by the number of total reads in each library were used to estimate the contig abundance (Porter et al., 2020).

2.4. PCR confirmation and genome annotation

Several contigs of pegiviruses were obtained from the libraries GXN (GX, Guangxi Province; N, bird) and XZS (XZ, Tibet; S, rat). The library was named by combing the first letter of Chinese Pinyin of both provincial name (sampling site) and host name. Accordingly, a number of paired primers were designed to amplify the gaps between contigs, and PCR products were analyzed by Sanger sequencing. The obtained Sanger sequences were assembled with the Illumina contigs by overlap sequences to get the full-length genome. For the pegivirus from the libraries QHN (QH, Qinghai Province; N, bird) and XZN (XZ, Tibet; N, bird), several primer pairs were designed to amplify the full-length genome, and were analyzed by Sanger sequencing to confirm the genomic sequences.

All pegiviruses identified in this study were subjected to online blastx search (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) against the Nr database, conserved domain (CDD) search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd), and prediction by Hmmer search (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/hmmer/) against the PFam database, respectively. The open reading frames (Merkle et al., 2010) were determined using the ORFfinder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) program of NCBI.

2.5. Phylogenetics and co-evolutionary analyses

In order to determine the evolutionary relationships of identified viral strains, the amino acid sequences (polyprotein, NS3 and NS5B) of the four new pegi-like viruses and all species of the genus Pegivirus were aligned using Mafft (Katoh and Standley, 2013). The sequence alignments were used to determine the most appropriate amino acid substitution model (Dayhoff) using Model Finder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017), and to construct the phylogenetic trees by PhyML v3.0 with 1000 bootstrap values (Guindon et al., 2010).

For the evaluation of coevolutionary analysis results, the phylogenetic tree of the vertebrate host species was inferred using TimeTree (Kumar et al., 2017). The phylogenetic trees of both host and virus (based on polyproteins) were input into the coevolutionary analysis using the Jane package v4 (Conow et al., 2010). The event costs were set as previously reported: 0 for cospeciation, 1 for duplication, 1 for duplication with host-switch, 1 for loss, and 1 for failure to diverge (Shi et al., 2018) and 0 for cospeciation, 1 for duplication, 2 for host-switching, 1 for loss and 1 for failure to diverge (Wang and Han, 2021), respectively. Finally, TreeMap3 was employed to visualize the coevolutionary tree showing the connections of each virus with its corresponding host species (Charleston, 2011). The “untangle” function was used to rotate the branches of one tree to minimize the number of crossed lines.

3. Results

3.1. Viral identification and genomic characterization

During 2018–2020, respiratory tract samples of 41 rodents and 67 wild birds were collected, and their total RNA were extracted and organized into four pools for meta-transcriptomics sequencing, including (1) library XZS (41 rodents from Cona County), (2) library XZN (31 wild birds from Cona County), (3) library QHN (23 wild birds from Yushu City), and (4) library GXN (13 wild birds from Zhaoping County) (Table 1). Sequencing of rRNA depleted libraries resulted in 66,147,908 to 213,111,136 paired reads, which were assembled into 583,930 to 678,034 contigs per library (Table 1). The abundance levels (reads per million) of the novel pegivirus genomes ranged from 0.061 to 19.548 RPM (Table 1).

Table 1.

Information on the RNA sequencing libraries.

| Library name | Virus | Host | Host organ | Library size | Total contigs | Pegi-like virus (nt) | Reads mapped | RPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QHN | MTPV | Birds | Respiratory tract | 213,111,136 | 647,840 | 10,866 | 4166 | 19.548 |

| GXN | PMPV | Birds | Respiratory tract | 100,507,574 | 678,034 | 10,916 | 606 | 0.061 |

| XZN | LBPV | Birds | Respiratory tract | 79,050,354 | 657,720 | 10,719 | 1072 | 13.561 |

| XZS | PLPV | Rodents | Respiratory tract | 66,147,908 | 583,930 | 11,430 | 586 | 8.859 |

PMPV, Passer montanus pegivirus; LBPV, Leucosticte brandti pegivirus; MTPV, Montifringilla taczanowskii pegivirus; PLPV, Phaiomys leucurus pegivirus; RPM, reads per million.

Two nearly full-length pegi-like viruses were identified from two libraries of wild bird, namely, libraries QHN and XZN, respectively (Table 1). In addition, several contigs (all belonging to pegivirus) were obtained from one bird library (i.e. library GXN) and one rodent library (i.e. library XZS). Next, specific primers were used to fill in the gaps to acquire the near complete length viral genomes. The four obtained viral genomes were confirmed using Sanger sequencing and named after their hosts’ species names (see next section), namely, Passer montanus pegivirus (PMPV) after the bird species (Passer montanus) from Zhaoping County, Leucosticte brandti pegivirus (LBPV) after the bird species (Leucosticte brandti) from Cona County, Montifringilla taczanowskii pegivirus (MTPV) after the bird species (Montifringilla taczanowskii) from Yushu City, and Phaiomys leucurus pegivirus (PLPV) after the vole species (Phaiomys leucurus) from Cona County.

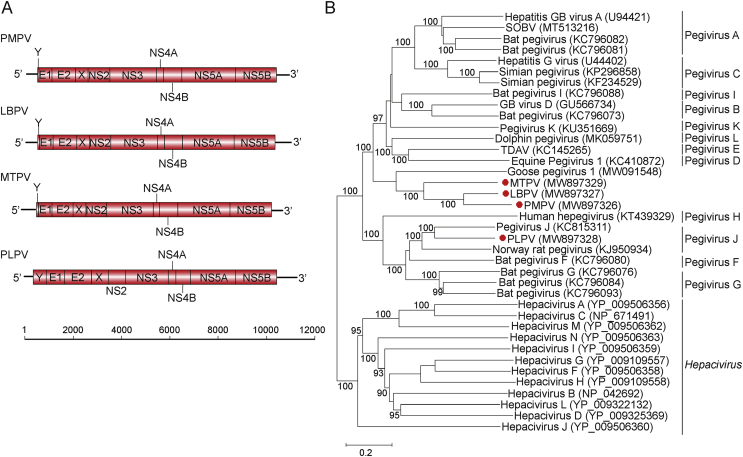

The genomes of LBPV (10,917 nt), MTPV (10,866 nt), PMPV (10,916 nt), and PLPV (11,430 nt) were comprised of 5′- and 3′-UTRs and a single ORF encoding complete polyproteins with 3,282, 3,282, 3,317, and 3426 amino acids (aa), respectively (Table 2). The G + C content of avian origin pegiviruses (LBPV, MTPV and PMPV) were 57.7%, 57.3% and 57.0%, respectively, which exhibited a similar pattern and were slightly lower than vole pegivirus (PLPV, 59.5%). The four pegiviruses identified here showed a prototypical genome architecture for pegiviruses (Fig. 1A), with a single ORF encoding a single polyprotein that can be cleaved into ten proteins, including three structural (Y, E1, E2) and seven non-structural (X, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, NS5B) proteins. PLPV exhibited similar length of polyprotein with that of its closely related members of Norway rat pegivirus isolate NrPgV/NYC-E13 (3340 aa) and Pegivirus J isolate CC61 (3484 aa), whereas LBPV, MTPV and PMPV revealed shorter length of polyprotein (3282–3317 aa) than Goose pegivirus 1 (3,430 aa). The feature comparison with known pegiviruses indicated that the NS5B protein acts as an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and the NS3 protein functions as a protease-helicase. The functions of other viral proteins were summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Predicted individual viral proteins of the pegivirus genomes identified in this study.

| Pegivirus | PMPV (aa) | LBPV (aa) | MTPV (aa) | PLPV (aa) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyprotein | 3317 | 3282 | 3282 | 3426 | |

| Y | 25 | 26 | 26 | 178 | Unknown function |

| E1 | 186 | 186 | 187 | 254 | Envelope glycoprotein |

| E2 | 328 | 327 | 311 | 373 | Envelope glycoprotein |

| X | 172 | 175 | 179 | 246 | Additional glycoprotein |

| NS2 | 302 | 297 | 288 | 241 | Membrane-associated protease |

| NS3 | 643 | 643 | 644 | 623 | Helicase and protease activities |

| NS4A | 97 | 97 | 97 | 109 | NS3 cofactor |

| NS4B | 256 | 250 | 256 | 212 | Replication complex formation |

| NS5A | 744 | 715 | 721 | 624 | Phosphorylation-dependent modulation of RNA replication |

| NS5B | 564 | 566 | 573 | 566 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

E, envelope glycoprotein; NS, nonstructural protein. PMPV, Passer montanus pegivirus; LBPV, Leucosticte brandti pegivirus; MTPV, Montifringilla taczanowskii pegivirus; PLPV, Phaiomys leucurus pegivirus.

Fig. 1.

Genomic annotation and genetic analysis. A Genomic structure of novel pegiviruses described in this study. B Phylogenetic analysis of novel pegiviruses based on polyproteins with 1000 bootstrap resampling. The clades of viruses identified in this study are labeled in red. The bootstrap value (%) was 1000 replicates with only bootstrap values > 90% shown. SOBV, Southwest bike trail virus; TDAV, Theiler's disease-associated virus; PMPV, Passer montanus pegivirus; LBPV, Leucosticte brandti pegivirus; MTPV, Montifringilla taczanowskii pegivirus; PLPV, Phaiomys leucurus pegivirus.

3.2. Screening and identification of pegiviruses from avian and rodent host species

Specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) for each pegivirus were designed based on each of the newly identified genomes to screen for the corresponding pegiviruses in individual respiratory tract samples. The sequencing of PCR products confirmed the presence of LBPV, MTPV, PMPV, and PLPV in 1/31 Leucosticte brandti (order Passeriformes, family Fringillidae), 4/23 ontifringilla taczanowskii (order Passeriformes, family Passeridae), 1/13 Passer montanus (order Passeriformes, family Ploceidae) and 7/41 Phaiomys leucurus (family Cricetidae) samples, respectively (Table 3). Therefore, each virus showed specific association with the corresponding hosts (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence and host species of pegiviruses identified in this study.

| Virus | Positive samples/test samples, n (%) | Host species | Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMPV | 1/13 (7.7) | Passer montanus | Zhaoping County |

| LBPV | 1/31 (3.2) | Leucosticte brandti | Cona County |

| PLPV | 7/41 (17.1) | Phaiomys leucurus | Cona County |

| MTPV | 4/23 (17.4) | Montifringilla taczanowskii | Yushu City |

PMPV, Passer montanus pegivirus; LBPV, Leucosticte brandti pegivirus; MTPV, Montifringilla taczanowskii pegivirus; PLPV, Phaiomys leucurus pegivirus.

3.3. Phylogenetic analysis

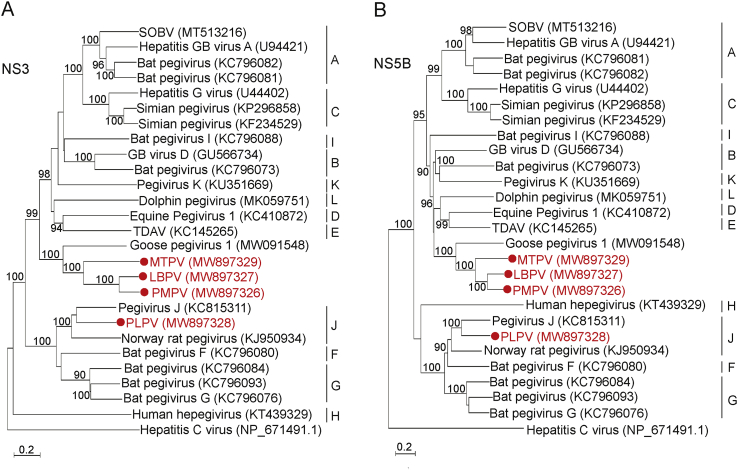

In order to infer the phylogenetic relationship of the newly identified pegiviruses, a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed based on full-length polyprotein amino acid alignment of the four novel viruses and other members of the Pegivirus genus. The results revealed that the three pegiviruses of avian origin (LBPV, MTPV and PMPV) were grouped with Goose pegivirus 1 within the genus Pegivirus and formed an independent clade that was sister to those identified from mammals, whereas PLPV was clustered together with two rat pegiviruses (Norway rat pegivirus isolate NrPgV/NYC-E13 and Pegivirus J isolate CC61) (Fig. 1B). The above phylogenetic topology based on polyprotein were consistent with those reconstructed based on NS3 and NS5B protein, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of pegiviruses based on NS3 (A) and NS5B (B) proteins. The clades of viruses identified in this study are labeled in red. The bootstrap value (%) was 1000 replicates with only bootstrap values > 90% shown. SOBV, Southwest bike trail virus; TDAV, Theiler's disease-associated virus; PMPV, Passer montanus pegivirus; LBPV, Leucosticte brandti pegivirus; MTPV, Montifringilla taczanowskii pegivirus; PLPV, Phaiomys leucurus pegivirus.

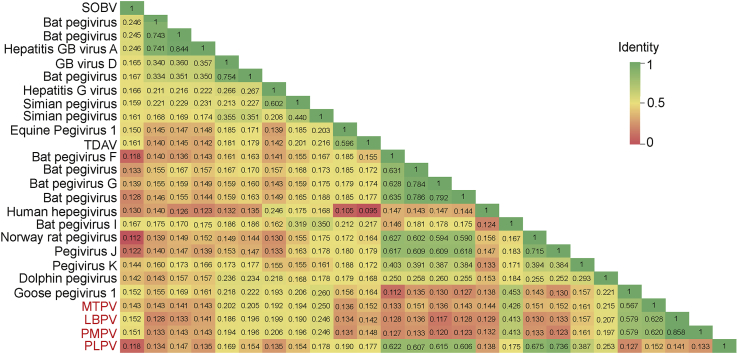

Similarity comparisons based on complete polyproteins showed that MTPV, PMPV and LBPV were closely related to Goose pegivirus 1 with 46.0%, 46.2%, 45.6% similarity, respectively, and PLPV was closely related to Norway rat pegivirus (54.5%). Also, we performed identity comparisons based on NS3 proteins (Fig. 3). The identities between the three avian pegiviruses (PMPV, LBPV, and MTPV) and other pegiviruses at NS3 protein regions were significantly low, indicating that these three avian pegiviruses were genetically distinct from known pegiviruses. Meanwhile, PLPV shared highest identity with Pegivirus J isolate CC61 (73.6%). Due to these four pegiviruses isolated from different host species from different regions and sharing low identities to known viruses, they might represent four new species, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Sequence identity matrix based on the NS3 amino acid alignment of newly described pegiviruses and members of the Pegivirus genus. The values and colors showed as identity. SOBV, Southwest bike trail virus; TDAV, Theiler's disease-associated virus; PMPV, Passer montanus pegivirus; LBPV, Leucosticte brandti pegivirus; MTPV, Montifringilla taczanowskii pegivirus; PLPV, Phaiomys leucurus pegivirus.

3.4. Co-evolutionary analyses

In order to further explore the evolutionary history of pegiviruses, the phylogenetic topologies of pegiviruses and their host were compared. Specifically, the relative frequency of four evolutionary events including host-dependent (codivergence) and host-independent events (duplication, host switch and loss) were evaluated (Merkle et al., 2010) (Fig. 4A) and compared against the null model. The result revealed a significant codivergence relationship for pegiviruses (P < 0.01), which was also reflected in the virus-host tanglegrams (Fig. 4B) Furthermore, the close association between virus and host was also reflected in the observation that majority of pegiviruses were associated with only one host (Fig. 4B), which were consistent with a previous report suggesting that pegiviruses were host-specific (Simmonds et al., 2017). Collectively, these results suggested a long-term evolutionary relationship between virus and host for the entire pegivirus genus.

Fig. 4.

Co-phylogenetic analysis of pegiviruses described in this study and members of the Pegivirus genus. A Relative frequency of coevolutionary events: co-divergence (blue), duplications (orange), host-switching (grey), loss (yellow). The centre lines, box limits, and whiskers of each boxplot indicate the estimated median, upper and lower quartiles, and 1.5 × interquartile range, respectively. B Tanglegram showing individual host-virus associations. SOBV, Southwest bike trail virus; TDAV, Theiler's disease-associated virus; PMPV, Passer montanus pegivirus; LBPV, Leucosticte brandti pegivirus; MTPV, Montifringilla taczanowskii pegivirus; PLPV, Phaiomys leucurus pegivirus.

4. Discussion

A novel rodent pegivirus and three novel bird pegiviruses were identified in this study using a combination of unbiased high-throughput sequencing and Sanger sequencing. The near-complete genome (about 11 kb) is re-constructed for all four pegiviruses, which encodes a complete polyprotein region that is generally observed among members within Flaviviridae. Meanwhile, these pegiviruses are highly diverse and show relatively low sequence identities both among known pegiviruses and with each. In addition to the PLPV described herein, a total of three rodent pegiviruses have been identified so far in rats (Kapoor et al., 2013; Firth et al., 2014). And, only four pegiviruses of avian origin are available now, with three of them identified in this study. Since more birds and rats species have not been examined for pegivirus, it is expected that more pegiviruses will be discovered in these two host groups.

Based on phylogenetic relationships, the genus Pegivirus were previously divided into two clades [Pegivirus A, B, C, D, E, I and K (clade 1) associated with bat, monkey, human and horse hosts, and Pegivirus F, G, H and J (clade 2) associated with bat, human and rat hosts], previously (Smith et al., 2016). In this study, we established a potentially third clade associated with birds, which included three bird pegiviruses (PMPV, LBPV and MTPV) grouped with goose pegivirus 1 that formed a sister clade to all mammalian pegiviruses (namely, both clade 1 and clade 2).

The identification of “avian-associated” pegiviruses are of particular interest to understand the evolutionary history of pegivirus, especially in the context of virus-host co-divergence, a hypothesis previously tested with data containing both hepacivirus and pegivirus (Porter et al., 2020) and now confirmed with pegivirus data alone. Indeed, with pegivirus diversity now established in multiple avian species, the common ancestor for all pegiviruses can now trace back to 312 (confidence interval: 294–323) million years old (Wang et al., 2013), before the divergence of mammals and bird, suggesting an ancient origin for the entire genera Pegivirus.

5. Conclusions

Herein, this work widens our knowledge about the Pegivirus genus of Flaviviridae and the genetic diversity of viruses in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the Guangxi Province of China, suggesting new avenues in evolution and the importance of further surveillance for pegiviruses. Since this exploratory work is based on small sample numbers, additional pegiviruses are likely to be identified in other bird and rodent hosts.

Data availability

Genomes of the four new pegiviruses were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MW897326- MW897329.

Ethics statement

The study practices were approved by Ethical Committee of the National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (NO: ICDC-2019012).

Author contributions

Zhu Wentao: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing - original draft. Yang Jing: data curation, funding acquisition, methodology, resources, validation. Lu Shan: resources, investigation. Huang Yuyuan: resources, investigation. Jin Dong: formal analysis, funding acquisition. Pu Ji: formal analysis, software. Liu Liyun: formal analysis, funding acquisition. Li Zhenjun: supervision. Shi Mang: funding acquisition, methodology, software, visualization, writing - review & editing. Xu Jianguo: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing - review & editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFC1200501 and 2019YFC1200505), Guangdong Province “Pearl River Talent Plan” Innovation and Entrepreneurship Team Project (2019ZT08Y464), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KQTD20200820145822023), General Administration of Customs, P.R. China (2019HK125), and Research Units of Discovery of Unknown Bacteria and Function (2018RU010).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2022.01.013.

Contributor Information

Mang Shi, Email: shim23@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Jianguo Xu, Email: xujianguo@icdc.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink B., Xie C., Huson D.H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgin C.J., Colella J.P., Kahn P.L., Upham N.S. How many species of mammals are there? J. Mammal. 2018;99:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Charleston M. TreeMap 3b. 2011. http://sitesgooglecom/site/cophylogeny Available:

- Conow C., Fielder D., Ovadia Y., Libeskind-Hadas, Jane R. A new tool for the cophylogeny reconstruction problem. Algorithm Mol. Biol. 2010;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth C., Bhat M., Firth M.A., Williams S.H., Frye M.J., Simmonds P., Conte J.M., Ng J., Garcia J., Bhuva N.P., Lee B., Che X., Quan P.L., Lipkin W.I. Detection of zoonotic pathogens and characterization of novel viruses carried by commensal Rattus norvegicus in New York City. mBio. 2014;5:e01933–1914. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01933-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M.G., Haas B.J., Yassour M., Levin J.Z., Thompson D.A., Amit I., Adiconis X., Fan L., Raychowdhury R., Zeng Q., Chen Z., Mauceli E., Hacohen N., Gnirke A., Rhind N., di Palma F., Birren B.W., Nusbaum C., Lindblad-Toh K., Friedman N., Regev A. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J.F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed M., Wahaab A., Nawaz M., Khan S., Nazir J., Liu K., Wei J., Ma Z. Potential role of birds in Japanese encephalitis virus zoonotic transmission and genotype shift. Viruses. 2021;13:357. doi: 10.3390/v13030357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B.A., Schmidt J.P., Bowden S.E., Drake J.M. Rodent reservoirs of future zoonotic diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:7039–7044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501598112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B.Q., Wong T.K.F., von Haeseler A., Jermiin L.S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor A., Simmonds P., Scheel T.K., Hjelle B., Cullen J.M., Burbelo P.D., Chauhan L.V., Duraisamy R., Sanchez Leon M., Jain K., Vandegrift K.J., Calisher C.H., Rice C.M., Lipkin W.I. Identification of rodent homologs of hepatitis C virus and pegiviruses. mBio. 2013;4:e00216–213. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00216-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Suleski M., Hedges S.B. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34:1812–1819. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manigold T., Vial P. Human hantavirus infections: epidemiology, clinical features, pathogenesis and immunology. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2014;144:w13937. doi: 10.4414/smw.2014.13937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle D., Middendorf M., Wieseke N. A parameter-adaptive dynamic programming approach for inferring cophylogenies. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11(Suppl. 1):S60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S1-S60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter A.F., Pettersson J.H., Chang W.S., Harvey E., Rose K., Shi M., Eden J.S., Buchmann J., Moritz C., Holmes E.C. Novel hepaci- and pegi-like viruses in native Australian wildlife and non-human primates. Virus Evol. 2020;6:veaa064. doi: 10.1093/ve/veaa064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey A.M., Reeves A.B. Ecology of influenza A viruses in wild birds and wetlands of Alaska. Avian Dis. 2020;64:109–122. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086-64.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues T.C.S., Subramaniam K., McCulloch S.D., Goldstein J.D., Schaefer A.M., Fair P.A., Reif J.S., Bossart G.D., Waltzek T.B. Genomic characterization of a novel pegivirus species from free-ranging bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the Indian River Lagoon, Florida. Virus Res. 2019;263:98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaluder G.G., Dawson G.J., Simons J.N., Pilot-Matias T.J., Gutierrez R.A., Heynen C.A., Knigge M.F., Kurpiewski G.S., Buijk S.L., Leary T.P., et al. Molecular and serologic analysis in the transmission of the GB hepatitis agents. J. Med. Virol. 1995;46:81–90. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890460117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M., Lin X.D., Chen X., Tian J.H., Chen L.J., Li K., Wang W., Eden J.S., Shen J.J., Liu L., Holmes E.C., Zhang Y.Z. The evolutionary history of vertebrate RNA viruses. Nature. 2018;556:197–202. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley S.D., Lauck M., Bailey A.L., Hyeroba D., Tumukunde A., Weny G., Chapman C.A., O'Connor D.H., Goldberg T.L., Friedrich T.C. Discovery and characterization of distinct simian pegiviruses in three wild African Old World monkey species. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds P., Becher P., Bukh J., Gould E.A., Meyers G., Monath T., Muerhoff S., Pletnev A., Rico-Hesse R., Smith D.B., Stapleton J.T. Ictv report C. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Flaviviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017;98:2–3. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.B., Becher P., Bukh J., Gould E.A., Meyers G., Monath T., Muerhoff A.S., Pletnev A., Rico-Hesse R., Stapleton J.T., Simmonds P. Proposed update to the taxonomy of the genera Hepacivirus and Pegivirus within the Flaviviridae family. J. Gen. Virol. 2016;97:2894–2907. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiakos G., Plavos K., Vontas A., Sofia M., Giannakopoulos A., Giannoulis T., Spyrou V., Tsokana C.N., Chatzopoulos D., Kantere M., Diamantopoulos V., Theodorou A., Mpellou S., Tsakris A., Mamuris Z., Billinis C. Phylogenetic analysis of bird-virulent West nile virus strain, Greece. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019;25:2323–2325. doi: 10.3201/eid2512.181225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Han G.Z. A sister lineage of sampled retroviruses corroborates the complex evolution of retroviruses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021;38:1031–1039. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Pascual-Anaya J., Zadissa A., Li W., Niimura Y., Huang Z., Li C., White S., Xiong Z., Fang D., Wang B., Ming Y., Chen Y., Zheng Y., Kuraku S., Pignatelli M., Herrero J., Beal K., Nozawa M., Li Q., Wang J., Zhang H., Yu L., Shigenobu S., Wang J., Liu J., Flicek P., Searle S., Wang J., Kuratani S., Yin Y., Aken B., Zhang G., Irie N. The draft genomes of soft-shell turtle and green sea turtle yield insights into the development and evolution of the turtle-specific body plan. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:701–706. doi: 10.1038/ng.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Han Y., Liu B., Li H., Zhu G., Latinne A., Dong J., Sun L., Su H., Liu L., Du J., Zhou S., Chen M., Kritiyakan A., Jittapalapong S., Chaisiri K., Buchy P., Duong V., Yang J., Jiang J., Xu X., Zhou H., Yang F., Irwin D.M., Morand S., Daszak P., Wang J., Jin Q. Decoding the RNA viromes in rodent lungs provides new insight into the origin and evolutionary patterns of rodent-borne pathogens in Mainland Southeast Asia. Microbiome. 2021;9:18. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00965-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Wu Y., Zhang W., Merits A., Simmonds P., Wang M., Jia R., Zhu D., Liu M., Zhao X., Yang Q., Wu Y., Zhang S., Huang J., Ou X., Mao S., Liu Y., Zhang L., Yu Y., Tian B., Pan L., Rehman M.U., Chen S., Cheng A. The first nonmammalian Pegivirus demonstrates efficient in vitro replication and high lymphotropism. J. Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01150-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Song W., Fan G., Yang J., Lu S., Jin D., Luo X.L., Pu J., Chen H., Xu J. Genomic characterization of a new coronavirus from migratory birds in Jiangxi Province of China. Virol. Sin. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12250-021-00402-x1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Yang J., Lu S., Jin D., Wu S., Pu J., Luo X.L., Liu L., Li Z., Xu J. Discovery and evolution of a divergent coronavirus in the Plateau Pika from China that extends the host range of Alphacoronaviruses. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:755599. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.755599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Yang J., Lu S., Lan R., Jin D., Luo X.L., Pu J., Wu S., Xu J. Beta- and novel delta-Virus Evol.onaviruses are identified from wild animals in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Virol. Sin. 2021;36:402–411. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00325-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Genomes of the four new pegiviruses were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MW897326- MW897329.