Abstract

Background

Since 1997, several tools based on the experiences of users and survivors of psychiatry have been developed with the goal of promoting self-determination in recovery, empowerment and well-being.

Objectives

The aims of this study were to identify these tools and their distinctive features, and to know how they were created, implemented and evaluated.

Method

This work was conducted in accordance with a published Scoping Review protocol, following the Arksey and O’Malley approach and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews. Five search strategies were used, including contact with user and survivor networks, academic database searching (Cochrane, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, SCOPUS, PubMed and Web of Science), grey literature searching, Google Scholar searching and reference harvesting. We focused on tools, elaborated by users and survivors, and studies reporting the main applications of them. The searches were performed between 21 July and 22 September 2022. Two approaches were used to display the data: descriptive analysis and thematic analysis.

Results

Six tools and 35 studies were identified, most of them originating in the USA and UK. Thematic analysis identified six goals of the tools: improving wellness, navigating crisis, promoting recovery, promoting empowerment, facilitating mutual support and coping with oppression. Of the 35 studies identified, 34 corresponded to applications of the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP). All of them, but one, evaluated group workshops implementations. The most common objective was to evaluate symptom improvement. Only eight studies included users and survivors as part of the research team.

Conclusions

Only the WRAP has been widely disseminated and investigated. Despite the tools were designed to be implemented by peers, it seems they have been usually implemented without them as trainers. Even when these tools are not aimed to promote clinical recovery, in practice the most disseminated recovery tool is being used in this way.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study

The scoping review included both mad maps and recovery tools, and the publications that evaluated or explored these resources.

Users and survivors’ networks were consulted, including those of international scope, in order to obtain any potentially relevant material for inclusion.

The scoping review included published articles and grey literature.

Although different networks of users and survivors in every continent were contacted, the researchers obtained no answer from any African network or organisation.

Introduction

In recent decades, mental health policy in many countries has undergone a paradigm shift towards a recovery-oriented approach. This is especially evident among Anglophone countries,1 although a similar path has been followed by several countries in northern Europe,2 and more recently by some countries or regions of southern Europe.3–5 This shift, which has been driven by international policy on mental health,6 7 is based on the social model of disability8 9 and aims to comply with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities,10 a primary goal being to promote user empowerment in mental health, both on a social/structural and individual level.11

Although very different interventions have been implemented under the umbrella of recovery,12 13 the main aim of all recovery-oriented programmes is to enable individuals to achieve a meaningful and satisfactory life in accordance with their own preferences and values, regardless of the presence of symptoms.14–16 This feature differentiates recovery-oriented interventions from those based on the biomedical model, which is mainly oriented towards symptom control17–19 as well as from psychiatric/psychosocial rehabilitation, the usual aim of which is the functional adaptation of the person to society.20 21

As recovery means living according to one’s own values and preferences, promotion and respect of self-determination have been identified as ‘the sine qua non of recovery-oriented practice (Mancini, p359)’.22 Self-determination has come to be regarded as a prerequisite for personal empowerment and recovery, and for regaining control over one’s own life.23–25 Accompanying a recovery process therefore implies promoting self-determination and providing people with the tools they need to direct their own process and make their own decisions.

In 1997, and with this goal in mind, Mary Ellen Copeland published the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP),26 which was followed 2 years later by Laurie Ahern’s and Daniel Fisher’s Personal Assistance in Community Existence (PACE): A Recovery Guide.27 Both are practical tools designed to promote self-determination and the active participation of people in their own recovery process.28

Since WRAP and PACE were published, a number of new tools have been developed. One of them is Madness and Oppression,29 that has been defined by the authors as a Mad Maps Guide, rather than a recovery tool. Specifically, they described them as follows:

Mad Maps are documents that we create for ourselves as reminders of our goals, what is important to us, our personal signs of struggle, and our strategies for self-determined well-being (The Icarus Project, p1).29

Both, mad maps and recovery tools are resources that were created by users and survivors of psychiatry, and they were born from the systematisation of the experience lived by people who dealt with emotional distress, mental health crisis or psychosocial diversity. Nowadays, both the users and survivors’ movements and the WHO highlight the importance of the recovery tools and mad maps. From the mad activism perspective, to put in value ‘the knowledge based on lived experience (experiential knowledge) that people with mental health problems can bring (Faulkner, p1)’.30 From the WHO, the recovery tools are considered essential for ‘adopting recovery and human rights approaches (World Health Organization, p11)’.31 That’s why, as part of their QualityRights Initiative, in 2019 the WHO published ‘Person-centred recovery planning for mental health and well-being self-help tool’,31 a tool that ‘draw substantially from WRAP (World Health Organization, p2)’.31

Despite there are different tools oriented to these objectives, only the WRAP has been widely disseminated and investigated.32 Other tools are less well known, either because they have not, unlike the WRAP, been used in mental health research, or because they have not been applied outside the context of certain user and survivor movements. Given this situation, there is a need to explore the literature to identify what tools are available in addition to the well-established WRAP and beyond those published in English. The scoping review method is an ideal approach for exploring and identifying programmes aimed at promoting self-determination and people’s active participation in their recovery processes. The advantage of this method is that it involves a broader exploration of the literature, integrating multiple research designs and addressing questions beyond intervention efficacy.33 More specifically, it allows us to explore and describe research activity, identifying gaps in relation to a particular topic, before summarising and disseminating the findings. It should also be noted that integrating multiple research designs is especially useful in fields which have not been systematically examined or disciplines with emerging evidence,33 as is the case of the tools referred to above. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to identify existing tools, produced by users and survivors, aimed at promoting recovery, empowerment and wellness in mental health. The secondary objectives were to explore the distinctive features of these tools, including how they have been created and implemented. The research questions guiding this scoping review were therefore as follows:

What tools, created by people with personal experience of mental health problems and recovery, are currently available for developing personal recovery plans and promoting the self-management of well-being?

What are their distinctive features?

How have they been created and implemented?

Methods

We conducted a scoping study in accordance with a published protocol34 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews.35 The framework used was that developed by Arksey and O’Malley,36 along with recommendations designed to enhance each phase.33 This approach suggests five stages to a scoping review:

Stage 1: identifying the research question

As recommended by Arksey and O’Malley,36 we formulated a broad research question aimed at identifying any tools created by people with any experience of mental health issues. As a scoping review is an iterative process, our original research question, set out in the protocol,34 was reformulated and expanded into the three questions listed above: What tools, created by people with personal experience of mental health problems and recovery, are currently available for developing personal recovery plans and promoting the self-management of well-being? What are their distinctive features? How have they been created and implemented?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

We started the searching process contacting networks of users and survivors, as well as some international mental health organisations. In addition, we asked them for suggestions about new networks, organisations, activists or academics to which we could send our query. Out of the 29 networks and entities contacted, 20 responded it (69%). Contact was made by email, from 21 July to 3 September 2021. Details are given in online supplemental table 1 and online supplemental table 2.

bmjopen-2022-061692supp001.pdf (222.8KB, pdf)

We conducted a literature search of the following databases: Cochrane database, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, SCOPUS, Pubmed and Web of Science. The key search terms initially selected were: action plan, crisis plan, crisis program, empowerment, making choice, mapping madness, Mapping Our Madness, own pace, Personal Assistance in Community Existence, taking action, Transformative Mutual Aid Practices, self-determination, self-management, recovery program, wellness, Wellness Recovery Action Plan, wellness recovery action planning. These were tested in order to refine and add, if necessary, new terms to the search strategy,33 as a result of which we incorporated madness and oppression. The search strategy used in the Web of Science was as follows: (“Wellness Recovery Action Plan*” OR “Personal Assistance in Community Existence” OR “Mapping Our Madness” OR “Transformative Mutual Aid Practices” OR “madness and oppression” OR “madness & oppression”) in topic. A grey literature search was also conducted in the databases EThOS and System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe. Only the most relevant titles were extracted for the following terms: Wellness Recovery Action Plan, Personal Assistance in Community Existence, Mapping Our Madness, Transformative Mutual Aid Practices, T-MAPS, madness and oppression, and madness & oppression. The search process in these databases was conducted between 4 and 7 September 2021.

A search for relevant articles was also conducted using Google Scholar (on 17 and 18 September 2021), applying the same search strategy and criteria as were used for grey literature databases. Only the first 100 search results were examined. We also examined the reference lists of included articles and conducted a manual search of specialised journals between 19 and 22 September 2021 (details in online supplemental table 3). Note that all searches were conducted without date restriction and covered records from any country or reported in any language, although the reports retrieved were mostly in English. The end date for all searches was 22 September 2021.

More details about the searching strategy and its results are given in online supplemental material.

Stage 3: study selection

The interesting abstracts were retrieved through the aforementioned search strategies, after identifying and removing duplicates. The process of study selection involved two main stages. First, two researchers independently inspected all the records and selected those whose title and/or abstract suggested they should be included. Next, copies of the full articles were obtained and examined to assess their relevance to the research question, while also considering the inclusion criteria (see below). Any disagreement at the point of full-text screening was resolved through discussion and consensus involving a third reviewer. Our initial focus, described in the protocol,34 was refined to: research papers, conference papers, Master’s and PhD dissertations, books and book chapters, manuals and research reports. The original inclusion criteria were also refined and resulted in the following inclusion criteria for tools:

They are aimed at promoting self-determination and empowerment of people in their mental health recovery process. Manuals, original presentation of a tool or workbooks, were considered for inclusion.

They are based on the recovery model.

They are created to elaborate a personalised strategy or plan.

They are comprehensive tools for improving well-being and recovery, that is, they are more than just a crisis plan.

They have been developed by people who are experiencing or have experienced a mental health issue and/or by user and survivor movements.

They may be used by any person who wishes to achieve health and well-being.

In the case of studies about tool applications, we considered the following inclusion criteria:

They are documents reporting the main applications of tools in people who experience any form of emotional distress and who wish to enhance their well-being.

They are studies involving participants aged 18 or over.

We excluded opinion articles, editorials and protocols. Meta-analyses and reviews were also excluded, although their reference lists were screened at the previous stage. Tools not developed from the perspective of users and survivors of psychiatry were also excluded.

Stage 4: data charting

A preliminary data charting framework involving 39 categories was described in the study protocol.34 This included a set of categories for describing the record (eg, type of document: manual, research report), characteristics of the tool (eg, type of application: individual, group) and characteristics of the study (eg, sample: type of participant). Consistent with the fact that data charting is an iterative process in which researchers extract and update data, we added one new category, focus on, to the previous framework so as to record the main aspects addressed by each tool.

In order to determine whether the resulting approach was suitable for answering the research questions and could be applied consistently,33 it was tested in a sample comprising 10% of the included documents. Two members of the team, working independently, charted each document. Any disagreement in the process was resolved in a consensus meeting involving all team members.

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

As described in the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley,36 we conducted both descriptive analysis and thematic analysis. Descriptive analysis involved the calculation of numerical frequencies regarding the tools identified (year of creation, countries and entities involved, and distinctive characteristics) and studies describing their application (tool used, study characteristics, participants’ characteristics). This analysis allowed us to identify the geographical locations of the literature and the main research methods used.33 In order to identify the primary focus of each tool, a thematic analysis was carried out and the topics were identified. Tools (manuals and descriptive material) were organised thematically by recurring themes and points of agreement and disagreement.37 38 All documents were reviewed independently by two researchers and summarised to extract information on tools and their implementation.

Patient and public involvement

The study is a collaboration between an association of users and survivors of psychiatry, a university, and the local Mental Health Services Administration. The research design and development have been led by members of the user and survivors’ associations. This characteristic has been crucial to contact with the representatives of the networks of users and survivors described at stage 2.

Results

Search findings

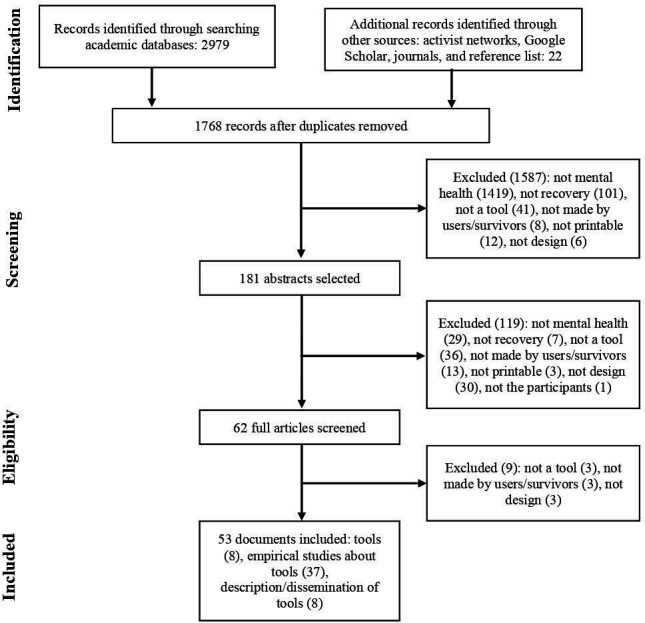

A list of 1758 registers was retrieved from the 6 search strategies used, after identifying and removing duplicate documents. Of them, 1587 documents were discarded by title and 119 were excluded by abstract. Finally, of the 62 full articles screened, 53 accomplished all the inclusion criteria and were included in this scoping review. The selection process is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selection process for study inclusion.

Descriptive analysis

A total of 62 records were retrieved from all the search strategies. Of these, 53 documents met the inclusion criteria: 8 were the tool itself (6 different tools in total), 8 were descriptions/dissemination of a tool and 37 were studies reporting the main applications of these tools. Three of these 37 studies were carried out by the same research group with the same population but with different goals and hence, they were considered as a single contribution in the descriptive analysis.

Tools

The six tools identified were developed between 1997 and 2018, and were as follows: WRAP,26 PACE,27 Mapping our Madness (MoM),39 Madness & Oppression: Paths to Personal Transformation & Collective Liberation (M&O),29 Transformative Mutual Aid Practices (T-MAPs)40 and Manual per a la Recuperació i Autogestió del Benestar (MRAB; in English: Manual for Recovery and Self-Management of Well-being).41 With the exception of the MRAB, all tools were developed in the USA and published in English. The MRAB was created in Catalonia (Spain) and was originally published in Catalan, with a Spanish version being published in 2020. Only the WRAP and PACE were identified through publications in indexed academic databases, with the remaining tools being found through contact with users and survivors’ networks.

All six tools are linked to users and survivors’ movements, mutual aid groups or peer support services. The MoM, M&O and T-MAPs define themselves as Mad Maps, and they emerged under the umbrella of The Icarus Project network. While the WRAP, PACE and MRAB present themselves as recovery tools, and they are associated with, respectively, the Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery, the National Empowerment Center, and the ActivaMent Catalunya Associació. The WRAP and MRAB were created in collaboration with mental health service providers, whereas the PACE, MoM and T-MAPs were developed exclusively by their authors, who systematised their own experience as members of a community of users and survivors. The M&O was a collective creation, involving 77 authors and ‘…dozens of people who wish to remain anonymous… (The Icarus Project, p4)’.29 Both the WRAP and the MRAB were developed through a participatory process. In the case of the WRAP, this included a recovery skills seminar (30 participants) and a survey (125 respondents),28 42 whereas the MRAB resulted from a process involving five focus groups (37 participants), a questionnaire (209 respondents), a 1 day series of thematic debates (48 participants) and 10 meetings of a coordinating committee (19 members).41

The tools include information about resources that people may wish to use in developing their recovery plans. The MRAB provides links to various websites so that people can explore the resources available to them locally, and it also includes a workbook as online supplemental material; the WRAP, MoM, M&O and T-MAPs incorporate a workbook within the manual itself. The purpose of these workbooks, which include questions and answer boxes, is to help people draw up their recovery plans. All the tools can, in theory, be used individually, although the WRAP, T-MAPs and MRAB have been designed to be implemented in a group workshop format with peers; the PACE has also been adapted for use in this format. In the case of M&O, this tool was developed exclusively for collective use. The MoM is the only tool designed to be used solely on an individual basis, with or without support from others. Regarding their application, the most common format for the WRAP is 8–12 sessions, whereas MRAB workshops are designed for 12 sessions. T-MAPs workshops include four modules, with a flexible number of sessions. The number of sessions is not specified or the PACE and M&O (table 1).

Table 1.

Tools and descriptive material

| Tool | Year | Author(s) | Material included in the review | Institution and country | Objectives | Focus on |

| Wellness Recovery Action Plan | 1997 | M.E. Copeland | Guide and Workbook,26 tool presentations24 28 42 | Copeland Center, USA | To identify the resources that each person has available to use for their recovery, and then using those tools to develop a guide to successful living that they feel will work for them.24 | Recovery, wellness, crisis |

| Personal Assistance in Community Existence | 1999 | L. Ahern and D. Fisher | Guide,27 tool presentation56 | National Empowerment Center, USA | To facilitate a consumers' complete recovery from ‘mental illness’ at their own pace, with an alternative noncoercive programme based on the principles of recovery, peer support, empowerment, and self-help.56 | Empowerment, recovery |

| Mapping our Madness | 2015 | Momo | Workbook39 | The Icarus Project, USA | To help folks map, plan, and navigate crisis, madness, or just foul moods | Crisis, wellness |

| Madness & Oppression | 2015 | The Icarus Project | Manual and workbook29 | The Icarus Project, USA | To create your own Mad Map, which serves as a reminder document for yourself and the people around you about your wellness goals, warning signs, strategies for health, and who you trust to look out for your best interests when you’re struggling. | Oppression, wellness, empowerment |

| Transformative Mutual Aid Practices | 2018 | J. McNamara and S. DuBrul | Manual and workbook,40 tool presentations54 55 78 | The Icarus Project, USA | To offer a set of tools that provide space for building a personal ‘map’ of wellness strategies, resilience practices, unique stories, and community resources. | Wellness, resilience, oppression |

| Manual per a la Recuperació i Autogestió del Benestar | 2018 | H.M. Sampietro and C. Gavaldà-Castet | Manual, workbook and workshops’ guide41 79 80 | Activa’t per la Salut Mental, ActivaMent Catalunya Associació, Catalonia, Spain | Facilitate the identification, organisation and management of the strategies and resources that people have at their disposal to develop their own personalised recovery and wellness plan. | Recovery, wellness, crisis |

Studies

The studies identified were published between 2005 and 2020, and all but one of them corresponded to applications of the WRAP; the other study referred to the PACE. The USA and the UK accounted, respectively, for 45.94% and 27.02% of this research output, which involved a total of 58 institutions or organisations, mainly universities (38 contributions) and mental health service providers or related government agencies (12 contributions). Only 7 mutual support and peer organisations participated in the studies identified, notably the Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery, and the Mental Health Recovery and WRAP.

The study regarding the PACE43 was the only one to involve a self-administered application of the tool, whereas all studies of the WRAP were carried out in group workshops. Twenty-two studies reported information on how workshops were delivered: In 13 studies, the workshops were offered by peers, in 6 they were facilitated by non-peer professionals, and 3 used a mixed professional/peer format.

In terms of study type, there were 20 quantitative studies, 12 qualitative studies and 3 that used mixed methods. Quasiexperimental and pre/post-test studies were the most common designs in quantitative research, whereas qualitative studies mainly used Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis37 38 or grounded theory. Data collections were carried out through questionnaires (19 studies), interviews (15 studies), focus groups (8 studies) and surveys (5 studies). The most commonly used questionnaire was the Recovery Assessment Scale.44

Only 8 studies were designed and conducted by or with the participation of users and survivors in the research team43 45–52 and a Leo McIntyre’s unpublished paper (see table 2). The remaining studies were designed and carried out exclusively from an academic or professional perspective. Research was mainly aimed at assessing symptom improvement (16 studies) or exploring self-perceived recovery (11 studies), knowledge and beliefs about recovery (6 studies) and the level of hope in recovery (6 studies).

Table 2.

Studies of the implementation of the tools

| Authors | Country | Tool |

| Afzal et al72 | Pakistan | WRAP |

| Ali68 | Palestine | WRAP |

| Aljeesh and Shawish69 | Palestine | WRAP |

| Ashman et al59 | UK | WRAP |

| Ben-Zeev et al81 | USA | WRAP |

| Carpenter-Song et al82 | USA | WRAP |

| Cook et al46 | USA | WRAP |

| Cook et al47 | USA | WRAP |

| Cook et al; Cook et al; Jonikas et al49–51 | USA | WRAP |

| Cook et al52 | USA | WRAP |

| Davidson65 | Scotland | WRAP |

| Doughty et al45 | New Zealand | WRAP |

| Elhelou70 | Palestine | WRAP |

| Fukui et al83 | USA | WRAP |

| Gordon and Cassidy60 | USA | WRAP |

| Higgins et al84 | Ireland, UK | WRAP |

| Horan and Fox85 | Ireland | WRAP |

| Jung et al66 | Korea | WRAP |

| Katayama et al71 | Japan | WRAP |

| Keogh et al86 | Ireland, UK | WRAP |

| Mak et al53 | China | WRAP |

| Matsuoka73 | Canada | WRAP |

| McIntyre87 | New Zealand | WRAP |

| O’Dwyer67 | UK | WRAP |

| O’Keeffe et al88 | Ireland, UK | WRAP |

| Olney and Emery-Flores61 | USA | WRAP |

| Petros62 | USA | WRAP |

| Petros and Solomon89 | USA | WRAP |

| Pratt et al63 | Scotland, USA | WRAP |

| Pratt et al64 | Scotland, USA | WRAP |

| Starnino et al90 | USA | WRAP |

| Stokoe and Bradbury91 | England | WRAP |

| Wilson et al92 | USA | WRAP |

| Zahniser et al43 | USA | PACE |

| Zhang et al48 | New Zealand | WRAP |

More information in online supplemental tables 4 and 5.

PACE, Personal Assistance in Community Existence; WRAP, Wellness Recovery Action Plan.

Most of the studies focused on symptoms were conducted solely from a professional or academic perspective; the exception are three studies made by the Judith Cook’s team.46 49–51 Attitudes and knowledge about recovery were the main topic in studies designed or carried out in collaboration with users and survivors.

All but one of the studies assessing the efficacy of the WRAP found significant improvements in most of the variables measured. The exception was the study conducted in Hong Kong by Mak et al,53 who only found significant improvement in perceived social support after WRAP workshops. This means that they did not observe any significant enhancement in relation to commonly measured variables such as empowerment, hope, self-stigma, social network size, symptom severity and subjective recovery.

Fourteen studies used a psychiatric diagnosis as an inclusion criterion, and they were all conducted from a professional perspective only. The criterion in 12 of these studies was a diagnosis of a severe mental disorder, which among participants was mainly bipolar disorder, major depression or schizophrenia. Of the remaining studies, 13 included users from mental health services. Seven studies included people with any form of emotional distress or who were interested in enhancing their well-being, and these participants did not self-identify as mental health service users. Three studies defined their participants as people with any experience of a mental health problem. Finally, three studies involved participants defined as from an ethnic minority and with psychosocial difficulties.

Thematic analysis

Table 3 summarises the main objectives of the tools.

Table 3.

Emerging topics from thematic analysis

| Goals | Tools that included |

| Improving wellness | All tools |

| Navigating crisis | All tools |

| Promoting empowerment | All tools (personal or social empowerment) |

| Facilitating mutual support | All tools |

| Promoting recovery | Some tools |

| Copping with oppression | Some tools |

Improving wellness

The tools identified are aimed at promoting wellness. The WRAP associates wellness with happiness, rather than with the absence of illness.26 Specifically, this tool defines wellness as the experience of feeling physically and emotionally well despite life’s daily challenges.42 In the MRAB, wellness is defined as being satisfied with one’s life or feeling comfortable with oneself.41 The M&O links wellness to participation in the community and its transformation.29 The T-MAPs similarly defines wellness from a social perspective, and it involves collectively building a world in which to live.54 55 Finally, the PACE and MoM do not define the concept of wellness, although they include several examples of activities and resources for promoting it.

The WRAP, T-MAPs and MRAB include a specific section for working on wellness, and some sections of the MoM and M&O are likewise aimed at helping users to reflect on or compile self-care or wellness resources. As for the PACE, it does not offer a specific section on wellness; however, under ‘Recovery Skills’ it addresses Self-Care Techniques, that is, things that people can do for themselves that make them feel good.27

Navigating crisis

The tools are also designed to help avoid or navigate crises, the meaning of which goes beyond the appearance of symptoms. In the WRAP, the concept of crisis refers to a loss of control over one’s life,26 and symptoms come to represent a crisis when people’s thoughts and feelings affect their ability to make decisions, take care of themselves or stay safe.28 The PACE defines a crisis as overwhelming stress, difficulties in integrating experiences and an interrupted development.56 The MoM similarly considers crises to be highly intense emotional states that affect thinking and communication.39 In the MRAB, a distinction is made between crisis as a synonym for clinical symptoms or relapse and life crises that profoundly affect a person’s way of life.41 The T-MAPs conceptualise crises both as experiences of emotional distress and as an opportunity for growth and transformation.40 Although the M&O does not define the concept of crisis, it gives several examples in sections such as: How does oppression affect your behaviour? or How does oppression make you sick?.29 Regarding the MoM, it defines itself on its cover as a Workbook for navigating crisis.39 The WRAP, MoM, M&O, T-MAPs and MRAB all regard crises as a fundamental issue for people to consider when drawing up their own recovery plan or map. The M&O and the T-MAPs contain specific sections oriented to reflecting on the social and structural causes of crises.

All tools, except the PACE, include specific sections dealing with knowing what to do (or not to do) to avoid a crisis, recognising the factors that can precipitate it, and identifying red flags when it starts. The WRAP, MoM, T-MAPs and M&O also have a section aimed at explaining to friends and relatives how the person needs and wants to be accompanied during a crisis. Another feature of the WRAP, MoM, T-MAPs and MRAB is a section on developing advance directives. Finally, the WRAP and MRAB include, respectively, sections headed Post-Crisis Plan and Learning Agenda. Both are focused on learning from crises, identifying what was useful and what was not.

Promoting recovery

The tools are aimed at promoting recovery. The WRAP, PACE and MRAB describe themselves as a recovery plan, guide or manual, and they each include sections on defining recovery and what is needed to promote it. The WRAP defines recovery as a process that helps people to improve their health and general wellness, lead an independent life and reach their full potential.26 For the PACE, recovery is a healing process that ‘allows people to (re)capture their dreams (Ahern, p5)’27 and to have an adult identity and a major social role.57 The MRAB uses Anthony’s definition of recovery, that is, a process through which a person develops new meaning and purpose in life such that it becomes satisfying.14

The WRAP defines five key concepts associated with recovery: hope, personal responsibility, self-advocacy, education and support.26 In the PACE, beliefs, relationships, skills, identity and community are considered the most important aspects to work on to promote a person’s recovery.27 The MRAB follows the 10 guiding principles of recovery set out by SAMHSA: hope, person-driven, many pathways, holistic, peer support, relationships, culturally based, trauma-based, strengths and responsibilities, and respect.58

Although the WRAP stresses that recovery goes beyond the clinical or functional dimension, it nonetheless defines itself as ‘a system for monitoring, reducing and eliminating uncomfortable or dangerous physical symptoms and emotional feelings’.28 Conversely, the PACE and MRAB make clear that recovery is not a clinical outcome, in other words, it is not synonymous with symptom remission.41 As for the T-MAPs, it does not aim to help the person return to a previous state of health, and instead it uses the concepts of transformation and resilience practices and promotes ‘a process of transformation and growth (McNamara, p3)’.40 The MoM and M&O do not use the concept of recovery or any equivalent. In the case of the MoM, users are encouraged to question interventions that seek to return them to some form of normality, rather than accepting and supporting ‘the different ways that all of our minds and bodies may function (Momo, p2)’.39

Promoting empowerment

The tools are resources that help to promote a process of empowerment. The PACE is specifically ‘based on the Empowerment Model of Recovery (Ahern, p16)’,27 while the MRAB is described as a model of self-management, self-determination and self-control aimed at promoting empowerment. The latter tool includes a section called Personal Growth Plan, defined as ‘the personal strategy of empowerment (Sampietro, p18)’.41

For the PACE, empowerment means ‘moving from dependence to self-determination (Fisher, p91)’,57 such that people take control of the important decisions that affect their lives and come to see themselves as competent members of society.

Four tools are primarily aimed at promoting empowerment on a personal level, which includes: promotion of self-determination, self-management and taking responsibilities (WRAP, PACE, MRAB); self-awareness, self-help, self-advocacy (WRAP, PACE); building self-esteem and personal confidence (WRAP, PACE); developing a positive sense of identity (not a sick role), challenging self-stigma (WRAP, PACE, MoM, MRAB); and creation of a meaningful life (WRAP, MRAB). By contrast, the M&O and T-MAPs seek primarily to promote empowerment at the social level, including identification of and reflection on the social structures of power, privilege and oppression, in addition to promoting participation in transformative collective practices in the community.29 40

Facilitating mutual support

All tools highlight the importance of mutual support or peer support practices for recovery, resilience, empowerment and/or the social change processes they seek to promote. This is made explicit in the name given to one of the tools, T-MAPs, whose authors describe it as ‘our attempt to help create a concrete framework for mutual aid (McNamara, p33)’.40

The PACE, M&O, T-MAPs and MRAB dedicate a section to exploring and promoting participation in mutual support or peer activities. The WRAP, in its updated edition, also includes a section called Appendix B: Peer Support.26 As for the MoM, although it highlights the value and importance of mutual support, it does not include a specific section on this.

The M&O and T-MAPs suggest that users share their own maps with other people in mutual support meetings.

Coping with oppression

Some of the tools aim to encourage reflection on the axes of oppression that affect emotional well-being. For instance, the M&O and T-MAPs include different sections for people to work individually and collectively on the specific axes of oppression that affect them (racism, sexism, ableism, classism, etc). In the case of the M&O, all the material is aimed at identifying the different forms of oppression that people encounter in life, and at helping them to recognise both how this oppression affects their wellness and how it can be responded to.

The PACE and MoM do not have a specific section dedicated to oppression, although they do include some reflection on the role of social, economic and cultural factors in the incidence of mental disorder and in recovery processes, highlighting the pathological effects of different forms of oppression. The PACE, M&O, MoM and T-MAPs consider the institution of psychiatry itself as an axis of oppression.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify and characterise tools developed by users and survivors of psychiatry and aimed at promoting recovery, empowerment and wellness. The scoping process identified six tools developed between 1997 and 2018, and a total of 37 studies published between 2005 and 2020. Five of the six tools originated in the USA and were originally published in English, the exception being the MRAB, which was developed in Catalonia (Spain) and published in Catalan. Three tools present themselves as a Mad Map and the other three as a Recovery Guide or Manual. Contact with networks of users and survivors proved crucial to discovering the tools, because only the WRAP and PACE were found in database searching. All tools emerged within the context of user and survivor movements, although their process of development varied depending on the movement. In addition to users and survivors, mental health service providers were also involved in developing the WRAP and the MRAB.

Of the 37 studies identified, they all, with the exception of one that involved the PACE, used the WRAP programme and were delivered as group workshops. The latter was a crucial aspect of the WRAP programme for many studies,48 59–64 it being considered that a group setting offers specific benefits: ‘…mutual identification, validation and support that emerges from delivering WRAP in a group environment (Ashman, p576)’.59 Several studies also regard peer-run workshops as being a key aspect of the WRAP,61 65–67 it being argued that peer facilitators serve as models and examples of recovery, improving participants’ hope.65 However, fewer than half of the studies reported that workshops were delivered by peers or with peers in the team.

Anglophone countries, primarily the USA and the UK, were the main contributors to research in this field. Only seven studies were carried out in non-English-speaking countries, namely Palestine,68–70 China,53 Japan,71 Korea66 and Pakistan.72 Contrary to most findings, one of these studies53 only observed a significant improvement in perceived social support after WRAP workshops. It should also be noted that only three studies aimed to explore the applicability of the WRAP programme in an ethnic minority.48 60 73 Two of these60 73 suggest integrating a critical analysis of oppression and a gender perspective in workshops, a focus which is not incorporated in the WRAP.

Quasiexperimental and pre/post-test studies were the predominant designs in quantitative research, whereas qualitative studies were mainly characterised by the use of grounded theory or Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis. Sample sizes varied across the studies, as did the criterion for inclusion, with some authors requiring an established diagnosis, while others included people reporting any kind of emotional distress. Universities and mental health services were the main institutions involved in the research. Although user and survivor organisations, such as the Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery, and the Mental Health Recovery and WRAP, also contributed to research output, the professional and academic perspective was predominant. Thus, while the tools themselves are the result of survivor research,30 most of the studies were designed and conducted without the participation of users and survivors. Moreover, even though recovery-oriented resources are not aimed at clinical recovery,14–16 the predominant focus of these studies was symptom reduction; notably, the few studies that did incorporate the perspective of users and survivors were focused instead on attitudes and knowledge about recovery43 45 48 (and the unpublished paper by McIntyre, 2005). In a similar vein, although there are numerous psychometric instruments aimed at measuring recovery,74 75 only two of those used in the studies were designed by or in conjunction with users and survivors as part of the research team: Doughty et al,45 and the Minnesota’ Survey in Cook et al.47 This illustrates how the perspective adopted by most of the studies does not take into account the epistemological and theoretical background of the tools used. Indeed, the studies tend to use the tools in a way akin to a psycho-educational programme, rather than as tools built from people’s experiential knowledge of their recovery processes.

Thematic analysis identified a total of six goals that form the primary focus of the tools: improving wellness, navigating crisis, promoting recovery, promoting empowerment, facilitating mutual support and coping with oppression. The first two of these goals, improving wellness and navigating crisis, are common to all tools, each of which acknowledges their importance and includes sections dedicated to working on these goals and/or strategies and examples of how to achieve them. The importance of mutual support for recovery, empowerment and/or coping with oppression is also highlighted by all six tools, and five of them were specifically designed to be used in a group setting with peers. Although some tools do not explicitly use the concept of empowerment, they all aim to promote it on some level11; the WRAP, PACE, MoM and MRAB promote certain aspects of personal empowerment, while the M&O and T-MAPs do the same with social empowerment. As regards the other two goals (ie, promoting recovery and coping with oppression), the tools differ in the stance they take. The M&O and MoM do not use the concept of recovery, and the T-MAPs refers to resilience rather than recovery, the reason being that these tools consider that the idea of ‘recovery’ suggests a return to a previous stage or to some state of supposed normality. Other tools (the MRAB) do refer to recovery but explicitly state that it does not mean going back to the past or being normal. Finally, coping with oppression is a specific focus of the M&O and T-MAPs, and it is also referred to at some point by the MoM and PACE. By contrast, the WRAP and MRAB do not offer any kind of reflection on the mental health system as a possible axis of oppression or on the negative effects of different kinds of oppression on people’s well-being. Coincidently, these are the only two tools to have been created in collaboration with mental health service providers.

Although the search process allowed us to identify and characterise tools created by users and survivors, certain gaps and limitations emerged. Notably, although this scoping review applied broad parameters and used several search strategies to map tools and their associated studies, the tools identified were developed, and most of the studies were conducted, in high-income countries with a recovery-oriented mental health system, in which there are well-established networks of users and survivors, and an Anglo-Saxon/Protestant cultural background that highlights individual freedom and self-determination.76 Therefore, the trends identified in the literature should be considered as representative of these kinds of contexts. More studies are needed to clarify the applicability and utility of the tools identified in other cultural contexts and for ethnic minorities. Furthermore, although we contacted different networks of users and survivors, including those of international scope, in every continent, we obtain no answer from any African network or organisation. This hindered the possible identification of additional material and the opportunity both to compare the recovery strategies used in non-Western contexts and to explore the extent to which the concept of recovery itself is applicable in those contexts.

Further research is likewise needed to examine the application and outcomes achieved with tools other than the WRAP. Once such studies begin to be conducted, it would be also be interesting to observe how they conceptualise recovery, wellness, crisis, empowerment, oppression and mutual support, and to see if they follow the original proposals of the tools’ authors or focus on evaluating different variables.

The underlying philosophy of the disability rights movement worldwide, ‘Nothing About Us Without Us’77 is the foundation of the tools built by user and survivor movements. However, very few studies have included users and survivors as subjects of knowledge, recognising and valuing their personal and collective experience as a source of learning, rather than seeing them as objects of intervention. A priority for future research is therefore to ensure the participation of users and survivors in the design, implementation and assessment of mental health recovery tools. Given that existing tools have come about thanks to the initiative of user and survivor networks, it is also important that this research is carried out from the perspective of survivor research and mad studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Correction notice: The article has been corrected since published online. The funding statement has been corrected.

Contributors: HMS developed the conceptual framework, carried out the thematic analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. VRC conceived the methodological framework and assisted with subsequent drafts of the manuscript. HMS and VRC performed the search process and the study selection, coded the data, and developed the descriptive analysis. JG-B assisted in the study selection and the process of coding. JG-B and JER supervised and provided regular feedback on each of these steps and contributed to revision of the final manuscript. HMS is the guarantor of this manuscript.

Funding: Project PID2019-109887GB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Not applicable.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, et al. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:445–52. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slade M, Amering M, Oades L. Recovery: an international perspective. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2008;17:128–37. 10.1017/s1121189x00002827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Generalitat de Catalunya . Pla integral d’atenció a les persones amb trastorn mental i addiccions 2017-2019 [Internet]. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya, 2017: 41. https://presidencia.gencat.cat/web/.content/departament/plans_sectorials_i_interdepartamentals/pla_integral_trastorn_mental_addiccions/docs/estrategia_2017_2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consejería de S de Castilla - La Mancha . Plan de salud mental de Castilla - La Mancha, 2018. Available: https://www.castillalamancha.es/sites/default/files/documentos/pdf/20190927/plan_salud_mental_2018-2025.pdf

- 5.Comitato I per Affari Europei . Linee guida per la definizione del Piano nazionale di ripresa e resilienza, 2020: 30. https://www.politicheeuropee.gov.it/media/5378/linee-guida-pnrr-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Mental health action plan 2013-2020. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013: p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization - Regional Office for Europe . The European Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020 [Internet]. World Health Organization, 2013: 26. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/280604/WHO-Europe-Mental-Health-Acion-Plan-2013-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver M. The social model of disability: thirty years on. Disabil Soc 2013;28:1024–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shakespeare T. The Social Model of Disability. In: Davis LJ, ed. The disability studies reader. IV. New York: Routledge, 2013: 214–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations . Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and Optional Protocol. [Internet]. New York: United Nations, 2006: 37. https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization - Regional Office for Europe . User empowerment in mental health – a statement by the WHO Regional Office for Europe [Internet]. WHO Regional Office for Europe. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2010: 1–13. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/113834/E93430.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson L, Roe D. Recovery from versus recovery in serious mental illness: one strategy for lessening confusion plaguing recovery. J Ment Health 2007;16:459–70. 10.1080/09638230701482394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuart SR, Tansey L, Quayle E. What we talk about when we talk about recovery: a systematic review and best-fit framework synthesis of qualitative literature. J Ment Health 2017;26:291–304. 10.1080/09638237.2016.1222056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1993;16:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shepherd G, Boardman J, Slade M. Making recovery a reality. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 2008: 20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.SAMHSA . Recovery for me mental health services: practice guidelines for Recovery- oriented care. SAMHSA, editor. Substance abuse and mental health services administration 2011.

- 17.Wade DT, Halligan PW. Do biomedical models of illness make for good healthcare systems? BMJ 2004;329:1398–401. 10.1136/bmj.329.7479.1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deacon BJ. The biomedical model of mental disorder: a critical analysis of its validity, utility, and effects on psychotherapy research. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:846–61. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deacon B, McKay D. The biomedical model of psychological problems: a call for critical dialogue. Lancet 2015;16:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bond GR, Resnick SG. Psychiatric rehabilitation. In: Frank RG, Elliott TR, eds. Handbook of rehabilitation psychology. American Psychological Association, 2000: 235–58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pilgrim D. 'Recovery' and current mental health policy. Chronic Illn 2008;4:295–304. 10.1177/1742395308097863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mancini AD. Self-determination theory: a framework for the recovery paradigm. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2008;14:358–65. 10.1192/apt.bp.107.004036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deegan PE. Recovery and empowerment for people with psychiatric disabilities. Soc Work Health Care 1997;25:11–24. 10.1300/J010v25n03_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Copeland ME. Self-determination in mental health recovery: taking back our lives. In: Jonikas JA, Cook JA, eds. National self-determination & psychiatric disability invitational conference [Internet]. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois, 2004: 68–82. https://www.theweb.ngo/history/recovery/UICsdconfdoc19.pdf#page=74 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piltch CA. The role of self-determination in mental health recovery. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2016;39:77–80. 10.1037/prj0000176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Copeland ME. Wellness recovery action plan. Updated Ed. Massachusetts: Human Potential Press, 1997: 144. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahern L, Fisher D. Personal assistance in community existence. A recovery guide. Lawrence, MA: National Empowerment Center, Inc, 1999: 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Copeland ME. Wellness recovery action plan: a system for monitoring, reducing and eliminating uncomfortable or dangerous physical symptoms and emotional feelings. Occup Ther Ment Heal 2002;17:127–50. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Icarus Project . Madness & Oppression: Paths to Personal Transformation & Collective Liberation [Internet], 2015: 60. https://fireweedcollective.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/MadnessAndOppressionGuide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faulkner A. Survivor research and Mad studies: the role and value of experiential knowledge in mental health research. Disabil Soc 2017;32:500–20. 10.1080/09687599.2017.1302320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization . Person-centred recovery planning for mental health and well-being. Who QualityRights self-help tool. Geneve: World Health Organization, 2019: 64. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-qualityrights-self-help-tool [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canacott L, Moghaddam N, Tickle A. Is the wellness recovery action plan (WRAP) efficacious for improving personal and clinical recovery outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2019:1–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sampietro HM, Carmona VR, Rojo JE, et al. Mapping mental health recovery tools developed by mental health service users and ex-users: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2020;10:e043957. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol 2017;12:297–8. 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Momo . Mapping our madness [Internet]. The Icarus Project, 2015. Available: www.theicariusproject.net

- 40.McNamara J, T-MAPs DSA. Transformative mutual aid practices [Internet]. Berkeley: TMAPs Community, 2018: 36. https://tmapscommunity.net/ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sampietro HM, Gavald -Castet C. Manual per a la recuperació i l’autogestió del benestar [Internet]. Barcelona: Mental, Activa’t per la Salut, 2018: 80. https://activament.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Manual-Recuperació-i-Autogestió-Benestar-R.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 42.Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery . The Way WRAP Works [Internet], 2014: 1–26. https://copelandcenter.com/sites/default/files/attachments/TheWayWRAPWorkswitheditsandcitations.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahniser JH, Ahern L, Fisher D. How the PACE program builds a recovery-transformed system: results from a national survey. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2005;29:142–5. 10.2975/29.2005.142.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giffort D, Schmook A, Woody C, et al. Construction of a scale to measure consumer recovery. Spingfield, IL: Illinois Office of Mental Health, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doughty C, Tse S, Duncan N, et al. The wellness recovery action plan (WRAP): workshop evaluation. Australas Psychiatry 2008;16:450–6. 10.1080/10398560802043705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cook JA, Copeland ME, Hamilton MM, et al. Initial outcomes of a mental illness self-management program based on wellness recovery action planning. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:246–9. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.2.246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cook JA, Copeland ME, Corey L, et al. Developing the evidence base for peer-led services: changes among participants following wellness recovery action planning (WRAP) education in two statewide initiatives. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2010;34:113–20. 10.2975/34.2.2010.113.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang W, Wong SY, Li Y. The wellness recovery action plan (wrap): effectiveness with Chinese. Aotearoa New Zeal Soc Work 2010;21. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cook JA, Copeland ME, Floyd CB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of effects of wellness recovery action planning on depression, anxiety, and recovery. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:541–7. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cook JA, Copeland ME, Jonikas JA, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial of mental illness self-management using wellness recovery action planning. Schizophr Bull 2012;38:881–91. 10.1093/schbul/sbr012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jonikas JA, Grey DD, Copeland ME, et al. Improving propensity for patient self-advocacy through wellness recovery action planning: results of a randomized controlled trial. Community Ment Health J 2013;49:260–9. 10.1007/s10597-011-9475-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cook JA, Jonikas JA, Hamilton MM, et al. Impact of wellness recovery action planning on service utilization and need in a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2013;36:250–7. 10.1037/prj0000028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.WWS M, Chan RCH, Pang IHY. Effectiveness of wellness recovery action planning (WRAP) for Chinese in Hong Kong. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2016;19:235–51. [Google Scholar]

- 54.DuBrul SA, Deegan P, Bello I. On Track NY. Peer Specialist ’s Manual [Internet]. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, 2017: 38. http://dev.omega.c4designlabs.net/content/CSC/csc-module-2/pdfs/OnTrackPeerSpecialistManualFinal2_17.17.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andersen J, Altwies E, Bossewitch J. Mad resistance/ mad alternatives: Democratizing mental health care. In: Rosenberg S, Rosenberg J, eds. Community mental health: challenges for the 21st century. 3rd edn. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2017: 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahern L, Fisher D. Recovery at your own pace. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2001;39:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fisher DB, Ahern L. Personal assistance in community existence (PACE): an alternative to PACT. Ethical Hum Sci Serv 2000;2:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . SAMHSA’s Working Definition of Recovery. 10 Guiding Principles of Recovery, 2011: 3. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ashman M, Halliday V, Cunnane JG. Qualitative investigation of the wellness recovery action plan in a UK NHS crisis care setting qualitative investigation of the wellness recovery action plan in a UK NHS crisis. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2017;38:570–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordon J, Cassidy J. Wellness recovery action plan (WRAP) training for BME women: an evaluation of process, cultural appropriateness and effectiveness. Glasgow: Scottish Recovery Network, 2009: 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olney MF, Emery-Flores DS. “I get my Therapy from Work”: Wellness Recovery Action Plan Strategies That Support Employment Success. Rehabil Couns Bull 2017;60:175–84. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Petros R. Learning and utilizing WRAP’S framework: the process of recovery for serious mental illness in Social Welfare Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy [Internet]. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania, 2017: 116. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/219377944.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pratt R, MacGregor A, Reid S, et al. Wellness recovery action planning (WRAP) in self-help and mutual support groups. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2012;35:403–5. 10.1037/h0094501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pratt R, MacGregor A, Reid S, et al. Experience of wellness recovery action planning in self-help and mutual support groups for people with lived experience of mental health difficulties. ScientificWorldJournal 2013;2013:1–7. 10.1155/2013/180587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davidson D. Social Problem Solving, Cognitive Defusion and Social Identification in Wellness Recovery Action Planning [Internet]. Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh, 2018: 190. https://era.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/33141/Davidson2018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jung SH, CM J, Kim SH. The effects of wellness recovery action plan (WRAP) as a peer support program on recovery for people with mental illness 2019;10. [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Dwyer D. #Twenty #First #Century #Recovery: Embracing Wellness, Self-Management, and the Positive Interface of Eastern and Western Psychology [Internet. London: University of London, 2015: 184. https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/14565/ [Google Scholar]

- 68.HMAS A. Effectiveness of Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) on Schizophrenic patients in Gaza strip [Internet]. Gaza: The Islamic University of Palestine, 2013: 191. https://195.189.210.17/bitstream/handle/20.500.12358/22095/file_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aljeesh YI, Shawish MA. The efficacy of wellness recovery action plan (wrap) on patients with major depressive disorder in Gaza strip. Int J Psychiatry 2018;3:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elhelou RY. The Effectiveness of Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) on Depression Disorder Patient in Gaza Strip [Internet]. Gaza: The Islamic University of Gaza, 2018: 128. https://library.iugaza.edu.ps/thesis/126028.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katayama Y, Morita Y, Mori M. Attempt to wellness recovery action plan for university students of multiple difficulties. The qualitative analysis of some feedback after classes. 41. Bulletin of Nagano University, 2019: 1–16. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/120006808836/ [Google Scholar]

- 72.Afzal T, Bashir K, Perveen A. Impact of the wellness recovery action plan (WRAP) on the psychiatric patient with symptoms of psychosis. Eval Stud Soc Sci 2020;9:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matsuoka AK. Ethnic/racial minority older adults and recovery: integrating stories of resilience and hope in social work. Br J Soc Work 2015;45:i135–52. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sklar M, Groessl EJ, Connell MO. Clinical psychology review instruments for measuring mental health recovery: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:1082–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Penas P, Iraurgi I, Moreno MC, et al. How is evaluated mental health recovery?: a systematic review. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2019;47:23–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hien J. The religious foundations of the European crisis. J Common Mark Stud 2017;57:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Charlton JI. Nothing about us without us: disability, oppression and empowerment. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1990: 215. [Google Scholar]

- 78.DuBrul SA. T-MAPs: Transformational Group Practices Outside the Mental Health and Criminal Justice Systems [Internet]. New York: Silberman School of Social Work, 2017: 15. https://www.mapstotheotherside.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/TMAPS_flier_websize.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sampietro HM, Gavald -Castet C. Quadern de treball personal: mapejant el meu benestar [Internet]. Barcelona: Activa’t per la Salut Mental, 2018: 60. https://activament.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Quadern-personal-de-treball-R.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sampietro HM, Gavald -Castet C. Guia per a la implementació de tallers basats en el Manual per a la Recuperació I Autogestió del Benestar. Barcelona: Activa’t per la Salut Mental, 2018: 155. https://www.activament.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Guia-actualitzat-des21.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ben-Zeev D, Brian RM, Jonathan G, et al. Mobile health (mHealth) versus clinic-based group intervention for people with serious mental illness: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv 2018;69:978–85. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carpenter-Song E, Jonathan G, Brian R, et al. Perspectives on mobile health versus clinic-based group interventions for people with serious mental illnesses: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Serv 2020;71:49–56. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fukui S, Starnino VR, Susana M, et al. Effect of wellness recovery action plan (wrap) participation on psychiatric symptoms, sense of hope, and recovery. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2011;34:214–22. 10.2975/34.3.2011.214.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Higgins A, Callaghan P, Keogh B. Evaluation of mental health recovery and wellness recovery action. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:2418–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Horan L, Fox J. Individual perspectives on the wellness recovery action plan (WRAP) as an intervention in mental health care. Int J Psychosoc Rehabil 2016;20:110–25. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Keogh B, Higgins A, Devries J, et al. 'We have got the tools': qualitative evaluation of a mental health wellness recovery action planning (wrap) education programme in Ireland. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2014;21:189–96. 10.1111/jpm.12068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McIntyre L. WRAP around New Zealand. unpublished paper. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 88.O'Keeffe D, Hickey D, Lane A, et al. Mental illness self-management: a randomised controlled trial of the wellness recovery action planning intervention for inpatients and outpatients with psychiatric illness. Ir J Psychol Med 2016;33:81–92. 10.1017/ipm.2015.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Petros R, Solomon P. Examining factors associated with perceived recovery among users of wellness recovery action plan. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2020;43:132–9. 10.1037/prj0000389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Starnino VR, Mariscal S, Holter MC, et al. Outcomes of an illness self-management group using wellness recovery action planning. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2010;34:57–60. 10.2975/34.1.2010.57.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stokoe N, Bradbury K. Self-managing mental health: the WRAP approach. Br J Ment Heal Nurs 2013;2:111–8. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wilson JM, Hutson SP, Holston EC. Participant satisfaction with wellness recovery action plan (wrap). Issues Ment Health Nurs 2013;34:846–54. 10.3109/01612840.2013.831505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061692supp001.pdf (222.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Not applicable.