Abstract

Aberrant activation of stimulator of interferon genes (STING) is tightly associated with multiple types of disease, including cancer, infection, and autoimmune diseases. However, the development of STING modulators for the therapy of STING‐related diseases is still an unmet clinical need. We employed a high‐throughput screening approach based on the interaction of small‐molecule chemical compounds with recombinant STING protein to identify functional STING modulators. Intriguingly, the cyclin‐dependent protein kinase (CDK) inhibitor Palbociclib was found to directly bind STING and inhibit its activation in both mouse and human cells. Mechanistically, Palbociclib targets Y167 of STING to block its dimerization, its binding with cyclic dinucleotides, and its trafficking. Importantly, Palbociclib alleviates autoimmune disease features induced by dextran sulphate sodium or genetic ablation of three prime repair exonuclease 1 (Trex1) in mice in a STING‐dependent manner. Our work identifies Palbociclib as a novel pharmacological inhibitor of STING that abrogates its homodimerization and provides a basis for the fast repurposing of this Food and Drug Administration‐approved drug for the therapy of autoinflammatory diseases.

Keywords: autoinflammatory diseases, colitis, cyclin‐dependent protein kinases, Palbociclib, stimulator of interferon genes

Subject Categories: Immunology, Pharmacology & Drug Discovery, Signal Transduction

Aberrant activation of STING is tightly associated with multiple types of diseases. Here, Palbociclib is identified as a pharmacological inhibitor of STING that can be repurposed for the therapy of STING‐driven autoimmune diseases.

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER)‐resident adaptor protein stimulator of interferon genes (STING) is widely expressed in immune cells such as antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) and T cells (Ishikawa & Barber, 2008). STING is engaged by its natural ligands including cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs) from bacterial sources or cyclic GMP‐AMP (cGAMP) generated by the cytosolic DNA sensor cGAMP synthase (cGAS; Ablasser et al, 2013; Su et al, 2019). The binding of CDNs to the STING dimer in the ER results in its translocation to the ER‐Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) region, where it recruits TANK‐binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and forms a STING‐TBK1 complex (Gui et al, 2019; Zhang et al, 2019; Zhao et al, 2019; Lepelley et al, 2020). TBK1‐mediated phosphorylation of IFN regulatory transcription factor 3 (IRF3) results in its dimerization and nuclear translocation and the subsequent production of type I interferons (IFNs; Ishikawa & Barber, 2008; Zhong et al, 2009; Ablasser et al, 2013; Sun et al, 2013). Moreover, STING mediates the activation of nuclear factor kappa‐B (NF‐κB) and the subsequent induction of proinflammatory cytokines (Abe & Barber, 2014; Dunphy et al, 2018; Balka et al, 2020). Very recent work revealed a primordial function of STING in inducing autophagy independently of TBK1 activation and interferon induction. STING‐containing ERGIC serves as a membrane source for LC3 lipidation and autophagosome biogenesis, which thereby plays a critical role in the clearance of DNA and viruses in the cytosol (Gui et al, 2019).

Stimulator of interferon genes activation plays an important role in mounting long‐lasting protective innate and adaptive immune responses (Lorenzo et al, 2018; Decout et al, 2021). Increasing evidence demonstrates that STING activation is vital for the elimination of invading pathogens, including viruses, bacteria and parasites (Luo et al, 2016; Nandakumar et al, 2019; Liang et al, 2022), vaccine development (Min et al, 2017), and cancer immunotherapy (Barber, 2015; Schadt et al, 2019). On the other hand, excessive release of type I IFNs through chronic overactivation of STING signaling has emerged as a central driver of several interferonopathies, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS), and STING‐associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI) (Gall et al, 2012; Jeremiah et al, 2014; Liu et al, 2014). These types of pathogenesis can be attributed to mutations of nucleases or STING. The DNase Three Prime Repair Exonuclease 1 (TREX1) mutation leads to inefficient degradation of self‐DNA and subsequent aberrant activation of the cGAS‐STING pathway with hyperproduction of chemokines and cytokines, leading to tissue damage in the scenario of SLE and AGS (Liu et al, 2014; Crow & Manel, 2015; Rice et al, 2015; McCauley et al, 2020). Similarly, several gain‐of‐function mutations of the STING gene lead to constitutive STING activation and drive the development of SAVI (Ahn et al, 2012; Jeremiah et al, 2014; Liu et al, 2014). Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of chronic, relapsing, immunological, and inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (Podolsky, 1991; Xavier & Podolsky, 2007; Ahn et al, 2017; Aden et al, 2018). Studies in mouse models of intestinal injury or barrier disruption have revealed an important role of STING in gut homeostasis (Ahn et al, 2017; Canesso et al, 2018; Martin et al, 2019). Moreover, the overt activation of STING exacerbates dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)‐induced colitis in mice (Martin et al, 2019; Hu et al, 2021). Considering its central role in the regulation of immune responses, STING has become an appealing target for the development of chemical agonists or inhibitors.

Canonical STING agonists are cyclic dinucleotide (CDN) analogs (Margolis et al, 2017; Luteijn et al, 2019). However, their clinical application has been largely hindered by their limited cytosolic accessibility (Diner et al, 2013) and instability caused by phosphodiesterase‐mediated degradation (Li et al, 2014). Derivatives based on native CDN structures and non‐nucleotide agonists have been developed in the past decades (Downey et al, 2014; Corrales et al, 2015; Fu et al, 2015), such as diABZIs (two symmetry‐related linked amidobenzimidazoles; Ramanjulu et al, 2019), PC7A (seven‐membered ring with a tertiary amine; Li et al, 2021) and SR‐717 (Chin et al, 2020). Meanwhile, both covalent and non‐covalent STING inhibitors have been developed for the treatment of autoimmune diseases (McCauley et al, 2020; Hong et al, 2021). For example, C‐176 and C‐178 were identified as inhibitors of mouse STING, and H151 was found to be an antagonist of both mouse and human STING by covalently targeting Cys91 of STING and blocking its palmitoylation, which attenuates STING‐mediated IFN‐β production and tissue damage in Trex1 knockout mice (Haag et al, 2018). Recent work demonstrated that C‐178 inhibited hyperinflammation in coatomer protein subunit alpha (COPA) syndrome resulting from defective retrograde membrane trafficking of STING to the ER caused by loss‐of‐function mutations in the COP‐α subunit of coatomer protein complex I (COPI). However, no STING inhibitors are currently approved for clinical use, and H151 investigations are still at the preclinical stage (Wu et al, 2020; Decout et al, 2021). Therefore, there is an urgent unmet need for the development of STING modulators for the therapy of STING‐related diseases.

In this study, we used a high‐throughput screening approach based on the interaction of small‐molecule chemical compounds with recombinant STING protein to identify functional STING modulators. Interestingly, the cyclin‐dependent protein kinase (CDK) inhibitor Palbociclib was found to bind to STING and inhibit STING‐mediated type I IFN responses. CDKs are protein serine/threonine kinases that belong to the CMGC family (CDKs, mitogen‐activated protein kinases, glycogen synthase kinases, and CDK‐like kinases; Malumbres & Oncology, 2006; Hunt et al, 2011). Palbociclib, together with Ribociclib and Abemaciclib, are all orally active selective reversible inhibitors of CDK4 and CDK6 which have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of hormone receptor‐positive (HR+) metastatic breast cancer in combination with specific endocrine therapies (Finn et al, 2015; Dickler et al, 2016).

Herein, we demonstrate that STING is a novel, direct target of Palbociclib. The binding of Palbociclib to STING impairs its activation and ameliorates features of autoimmune disease resulting from DSS treatment or the genetic deletion of Trex1−/− in mice. Our work identifies Palbociclib as a novel pharmacological inhibitor of STING that interrupts its homodimerization. The repurposing of the FDA‐approved drug Palbociclib could lead to the rapid development of approved clinical treatments for diseases precipitating from constitutive STING activation.

Results

Identification of STING‐binding small molecular compounds by high‐throughput screening and validation of the regulatory effects of candidate compounds on STING activation

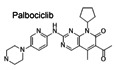

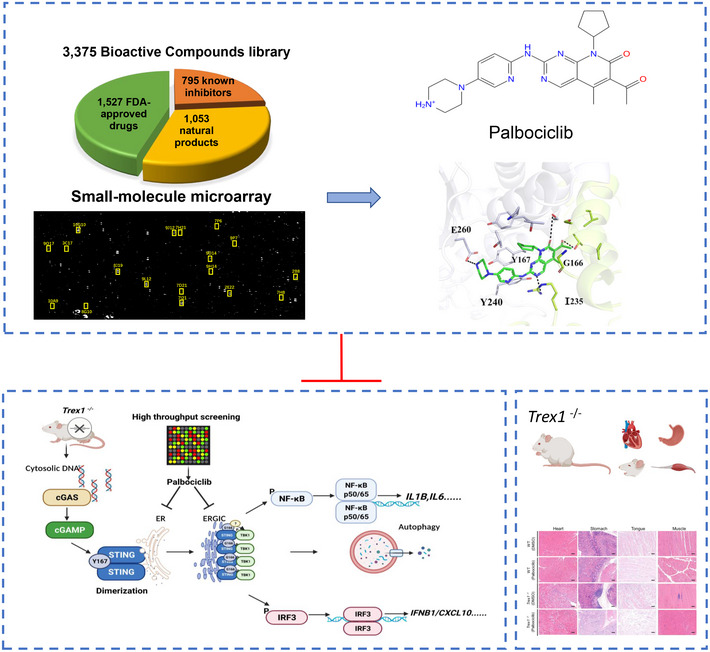

Stimulator of interferon genes has emerged as an important therapeutic target for inflammatory diseases and cancer (Barber, 2015; Motwani et al, 2019), which has led to multiple studies aiming to identify STING modulators (Downey et al, 2014; Haag et al, 2018; Li et al, 2018). Here, we employed a high‐throughput screening platform based on the detection of molecular interactions, which has been successfully used for the identification of target protein‐binding compounds (Fei et al, 2010; Li et al, 2019). By using a chip labeled with 3,375 bioactive small chemical molecules including 1,527 FDA‐approved drugs, 795 known inhibitors, and 1,053 natural products (Fig 1A and 1B) (Zhu et al, 2016), we found 18 small‐molecule compounds that interact with STING (Fig 1C). Detailed information on the compounds is given in Table 1.

Figure 1. Identification of STING‐binding small‐molecule compounds by high‐throughput screening and validation of the regulatory effects of compound hits on STING activation.

-

AOI‐RD image of a small‐molecule microarray (SMM). Each compound was printed in duplicate in adjacent vertical positions.

-

BThe categories of the compound library. About 3,375 compounds were printed on the chip, including 1,527 FDA‐approved drugs, 1,053 natural products, and 795 known inhibitors.

-

CRepresentative image showing the binding of recombinant STING protein to compounds printed on HTS chip. The SMM chip was titrated to purified STING protein observing emission from 300 to 400 nm at 1 nm intervals (excitation 290 nm). Scans were done in triplicates per sample. Excitation and emission slits were set to 5 nm. A2 = 8J19; A3 = 10A9; A4 = 9O17; A5 = 3C17; A6 = 7H8; A7 = 8G10; A8 = 9H14; A9 = 10G10; A10 = 7D21; A11 = 9J12; B2 = 9L12; B3 = 7H21; B4 = 2B8; B5 = 9D14; B6 = 9P7; B7 = 2E22; B8 = 7P6; B9 = 7I21.

-

D, EqRT‐PCR measurement of Ifnb1 transcripts in mouse peritoneal macrophages that were left unstimulated or stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) (D) or ISD (1 μg/ml) (E) for 4 h in the presence of DMSO or indicated compounds (10 μM). The data are presented as the relative fold induction of Ifnb1/Gapdh transcripts. A 90% reduction of IFNB1 transcripts in mouse peritoneal macrophages in comparison to the DMSO group was selected as the cutoff value for follow‐up study, which has been indicated by the red dashed line. The arrow indicates the group that meets the cutoff value. The data shown are mean ± SEM from n = 3 biological replicates.

Table 1.

Candidate STING binding small molecular compounds identified by high throughput screening.

| Product name | Plate location | CAS No. | M.Wt | Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palbociclib (hydrochloride) | A2 | 827022‐32‐2 | 483.99 | CDK |

| Istradefylline | A3 | 155270‐99‐8 | 384.43 | Adenosine Receptor |

| WHI‐P154 | A4 | 211555‐04‐3 | 376.20 | EGFR; JAK |

| Esmolol (hydrochloride) | A5 | 81161‐17‐3 | 331.83 | Adrenergic Receptor; Autophagy; Mitophagy |

| Salubrinal | A6 | 405060‐95‐9 | 479.81 | Autophagy; Phosphatase |

| Ibuprofen | A7 | 15687‐27‐1 | 206.28 | COX‐1/COX‐2 |

| Famotidine | A8 | 76824‐35‐6 | 337.45 | Histamine Receptor |

| Acacetin | A9 | 480‐44‐4 | 284.26 | Potassium Channel |

| Valdecoxib | A10 | 181695‐72‐7 | 314.36 | COX |

| Phenazopyridine (hydrochloride) | A11 | 136‐40‐3 | 249.70 | Others |

| Moguisteine | B2 | 119637‐67‐1 | 339.41 | Others |

| Caspofungin (Acetate) | B3 | 179463‐17‐3 | 1213.42 | Fungal |

| Diclazuril | B4 | 101831‐37‐2 | 407.64 | Parasite |

| BMS‐378806 | B5 | 357263‐13‐9 | 406.43 | HIV |

| Intepirdine | B6 | 607742‐69‐8 | 353.44 | 5‐HT Receptor |

| Dichlorphenamide | B7 | 120‐97‐8 | 305.16 | Carbonic Anhydrase |

| Proflavine (hemisulfate) | B8 | 1811‐28‐5 | 258.29 | Autophagy; Bacterial |

| Azilsartan | B9 | 147403‐03‐0 | 456.45 | Angiotensin Receptor |

To determine whether these STING‐interacting compounds affect STING activation, we stimulated peritoneal macrophages with cGAMP in the presence of the compounds or DMSO as the solvent control. The A2 compound, which is the CDK inhibitor Palbociclib (Baughn et al, 2006), caused more than 90% reduction in the induction of Ifnb1 transcripts in response to stimulation with 2’3’‐cGAMP or immunostimulatory DNA (ISD) in mouse peritoneal macrophages (Fig 1D and E). These data suggested that Palbociclib may impair type I IFN responses by targeting STING.

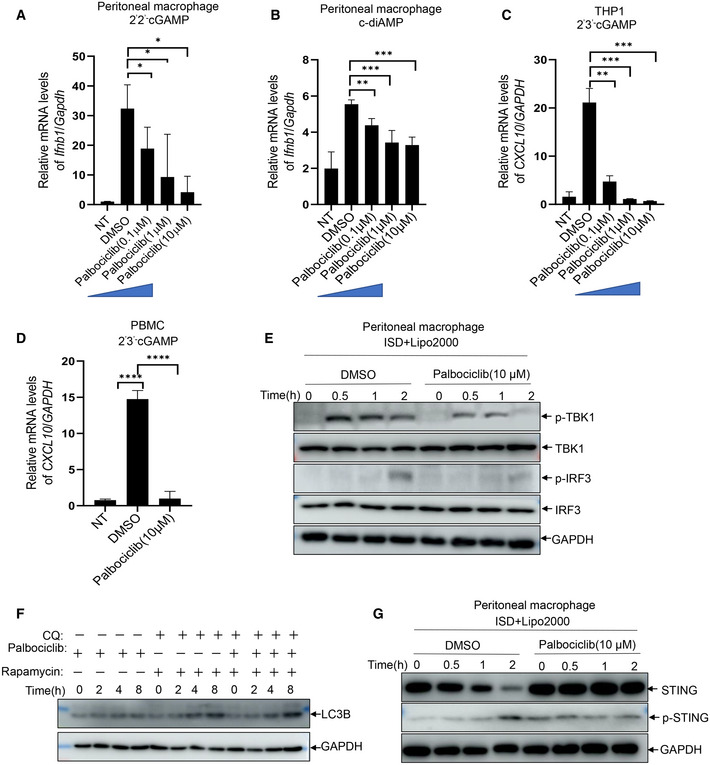

Palbociclib is highly potent at abrogating STING activation, independently of its canonical CDK target

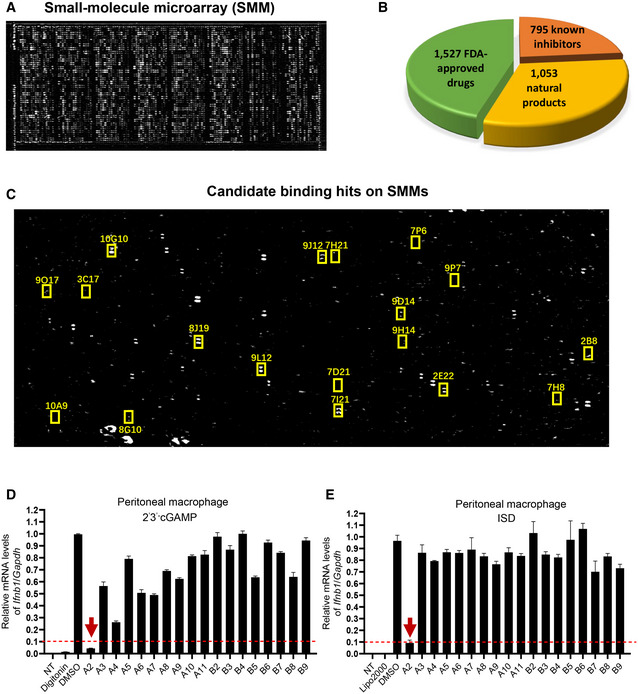

To verify the effect of Palbociclib on STING activation, we measured the induction of type I IFN responses to various CDNs. Palbociclib inhibited the transcription of Ifnb1 and Cxcl10 in a dose‐dependent manner in response to different STING agonists, including 2’3’‐cGAMP, 2’2’‐cGAMP, and c‐diAMP, in primary mouse macrophages (Figs 2A and EV1A and B). Moreover, Palbociclib markedly reduced the expression of IFNB1 and CXCL10 in human THP1 cells and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs; Figs 2B and C, and EV1C and D). Notably, Palbociclib treatment did not significantly affect the viability of any of the cell types examined (Fig 2D), indicating that the inhibitory effect of Palbociclib on type I IFN responses is not due to cytotoxicity of Palbociclib.

Figure 2. Palbociclib is highly potent in abrogating STING activation.

-

A–CqRT‐PCR measurement of Ifnb1 transcripts in mouse peritoneal macrophages (A), THP1 cells (B), and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (C) that were left unstimulated or stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) for 4 h in the presence of DMSO or indicated concentrations of Palbociclib (0.1, 1, 10 μM). The data are presented as fold induction of Ifnb1/Gapdh transcripts. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by one‐way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post‐hoc test. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001.

-

DMTS detection of the viability of mouse peritoneal macrophages (PM), THP1, and PBMC cells left untreated (DMSO) or treated with Palbociclib (1 μM, 10 μM) for 4 h. The data shown are mean ± SEM from n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by one‐way ANOVA. ns, not significant.

-

E, FImmunoblotting of indicated proteins in the lysates of mouse peritoneal macrophages (E) and THP1 cells (F) stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM) for indicated times. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

G, HqRT‐PCR measurement of Il1b (G) and Il6 (H) transcripts in mouse peritoneal macrophages left unstimulated or stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM) for indicated times. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post‐hoc test. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

-

I, JqRT‐PCR measurement of Il1b (I) and Il6 (J) transcripts in THP1 cells left unstimulated or stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM) for indicated times. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post‐hoc test. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

-

K, LImmunoblotting of indicated proteins in the lysates of mouse peritoneal macrophages (K) and THP1 (L) cells stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM) for indicated times. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

M, NImmunoblotting of indicated proteins in the lysates of mouse peritoneal macrophages (M) and THP1 (N) cells stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

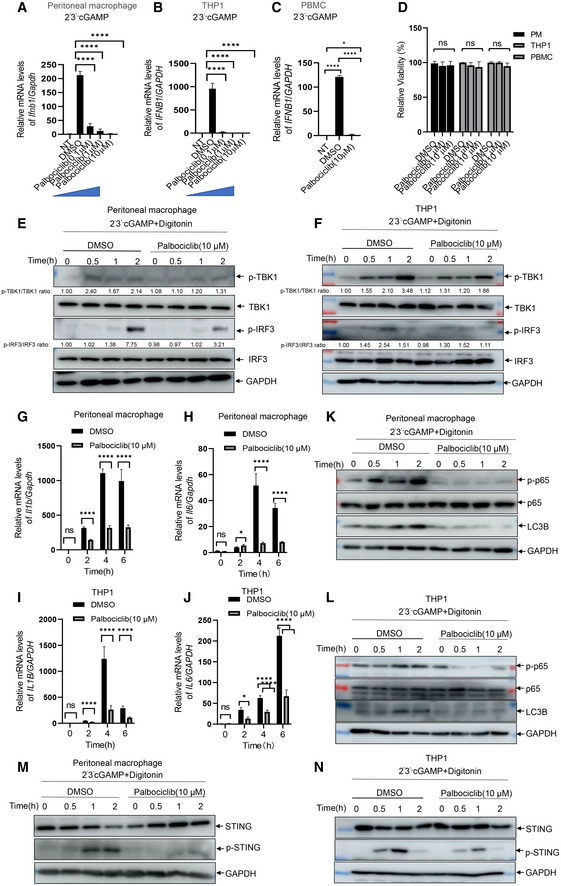

Figure EV1. Palbociclib inhibits STING activation.

-

A, BqRT‐PCR measurement of Ifnb1 transcripts in mouse peritoneal macrophages that were left unstimulated or stimulated with CDNs including 2'2' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) (A) and c‐di‐AMP (0.1 μg/ml) (B) for 4 h in the presence of DMSO or indicated concentrations of Palbociclib (0.1, 1, 10 μM). The data are presented as fold induction of Ifnb1/Gapdh transcripts. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by one‐way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post‐hoc test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

-

C, DqRT‐PCR measurement of CXCL10 transcripts in THP1 cells (C) and PBMC (D) that were left unstimulated or stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) for 4 h in the presence of DMSO or indicated concentrations of Palbociclib (0.1, 1, 10 μM). The data are presented as fold induction of CXCL10/GAPDH transcripts. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by one‐way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post‐hoc test. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

-

EImmunoblotting of indicated proteins in the lysates of mouse peritoneal macrophages transfected with ISD (1 μg/ml) in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

FImmunoblotting of indicated proteins in the lysates of mouse peritoneal macrophages that were left unstimulated or stimulated with rapamycin (100 nM) and chloroquine (10 μM) for 4 h in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

GImmunoblotting of indicated proteins in the lysates of mouse peritoneal macrophages transfected with ISD (1 μg/ml) in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

The engagement of STING by its agonists leads to activation of signaling cascades, including the activation of TBK1 and transcription factor IRF3. Stimulation of mouse peritoneal macrophages with either cGAMP or ISD induced the phosphorylation of TBK1 and IRF3, which was markedly reduced by Palbociclib (Figs 2E and EV1E). In addition, Palbociclib consistently reduced cGAMP‐induced phosphorylation of TBK1 and IRF3 in human THP‐1 cells (Fig 2F). These data indicate that Palbociclib may impair STING‐mediated signaling activation in both mouse and human immune cells. In addition to its activation of the TBK1‐IRF3‐Type I IFN signaling pathway, STING also mediates the activation of NF‐κB and the subsequent induction of proinflammatory cytokines (Barber, 2015; Jeremiah et al, 2014). Of note, treatment of both mouse macrophages and human THP1 cells by Palbociclib markedly inhibited cGAMP‐induced transcription of Il1b and Il6 (Figs 2G–J) as well as NF‐κB activation (Fig 2K and L). Recently, it has been reported that STING activates autophagy using a mechanism independent of TBK1 activation and interferon induction (Kim & Guan, 2015; Sotthibundhu et al, 2016; Gui et al, 2019). In line with these reports, cGAMP treatment induced LC3 lipidation, which is a hallmark of autophagy (Fig 2K and L). Intriguingly, Palbociclib largely abrogated cGAMP‐induced autophagy (Fig 2K and L). However, rapamycin‐induced autophagy was not affected by Palbociclib (Fig EV1F). Taken together, our findings show that Palbociclib blocks multiple STING downstream effectors, including both TBK1‐dependent inflammatory responses and TBK1‐independent autophagy. It is well documented that the activation of STING leads to its phosphorylation and degradation (Konno et al, 2013; Lorenzo et al, 2018). Stimulation of mouse peritoneal macrophages with either cGAMP or ISD consistently resulted in the phosphorylation of STING on serine 366, concurrent with a reduction in the protein levels of STING, while the presence of Palbociclib abrogated such processes (Figs 2M and EV1G). Moreover, Palbociclib also markedly inhibited cGAMP‐induced phosphorylation and degradation of STING in human THP‐1 cells (Fig 2N). These data indicate that Palbociclib may target STING itself or function upstream of STING.

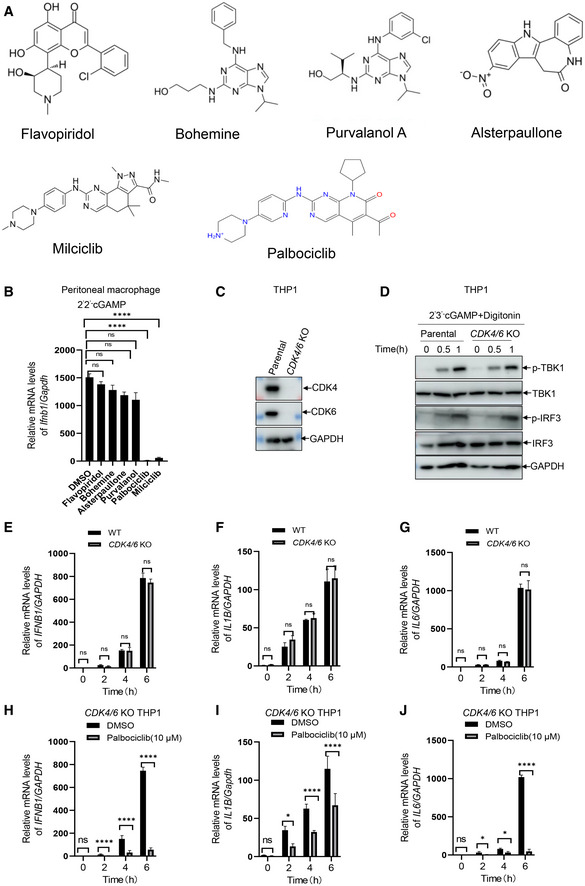

Inhibition of CDK activity by R547 or knockdown of CDK expression revealed that CDK activity is critical for the translation of IFN‐β without affecting its transcription in response to the initial nucleic acid sensing (Cingz & Goff, 2018). Consistently, we found that inhibition of CDK activity by different compounds including Flavopiridol, Bohemine, Alsterpaullone, and Purvalanol did not significantly reduce the level of Ifnb1 transcripts in mouse macrophages in response to cGAMP stimulation (Fig EV2A and B). Intriguingly, a structural analog of Palbociclib, Milciclib, also inhibited cGAMP‐induced transcription of Ifnb1 (Fig EV2A and B), indicating that the structure rather the kinase activity of Palbociclib may be largely responsible for its inhibitory effect on STING. To clarify whether CDK4 and CDK6, the canonical targets of Palbociclib, were required for Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING, we generated CDK4/6 knockout THP1 cells by CRISPR/Cas‐mediated genome editing with guide RNAs targeting CDK4 and CDK6 (Fig EV2C). The deletion of CDK4 and CDK6 did not significantly affect cGAMP‐induced phosphorylation of TBK1 and IRF3 or the induction of IFNB1, IL1B, and IL6 transcripts in THP1 cells (Fig EV2D–G). Importantly, Palbociclib still showed inhibitory effects on STING‐induced type I IFN responses in CDK4/6 knockout THP1 cells (Fig EV2H–J), indicating that Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING activity is not an epiphenomenon of CDK inhibition.

Figure EV2. Palbociclib inhibits STING activation independent of CDK4/6.

-

AChemical structures of five different CDK inhibitors including Flavopiridol, Bohemine, Purvalanol A, Alsterpaullone, and Milciclib.

-

BqRT‐PCR measurement of Ifnb1 transcripts in mouse peritoneal macrophages stimulated with 2'2' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) in the presence of DMSO or indicated CDK inhibitors including Flavopiridol, Bohemine, Alsterpaullone, Purvalanol, and Milciclib as well as Palbociclib. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by one‐way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post‐hoc test. ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

-

CImmunoblotting of indicated proteins in the lysates of THP1 cells stably transfected with guide RNA targeting both CDK4 and CDK6 (CDK4/6 KO). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

DImmunoblotting of indicated proteins in the lysates of parental THP1 cells and CDK4/6 knockout THP1 cells stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) for indicated times. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

E, GqRT‐PCR measurement of IFNB1, IL6, and IL1B transcripts in parental THP1 cells and CDK4/6 knockout THP1 cells stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) for indicated times. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post‐hoc test. ns, not significant.

-

H–JqRT‐PCR measurement of IFNB1, IL6, and IL1B transcripts in CDK4/6 knockout THP1 stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) for indicated times in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post‐hoc test. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Source data are available online for this figure.

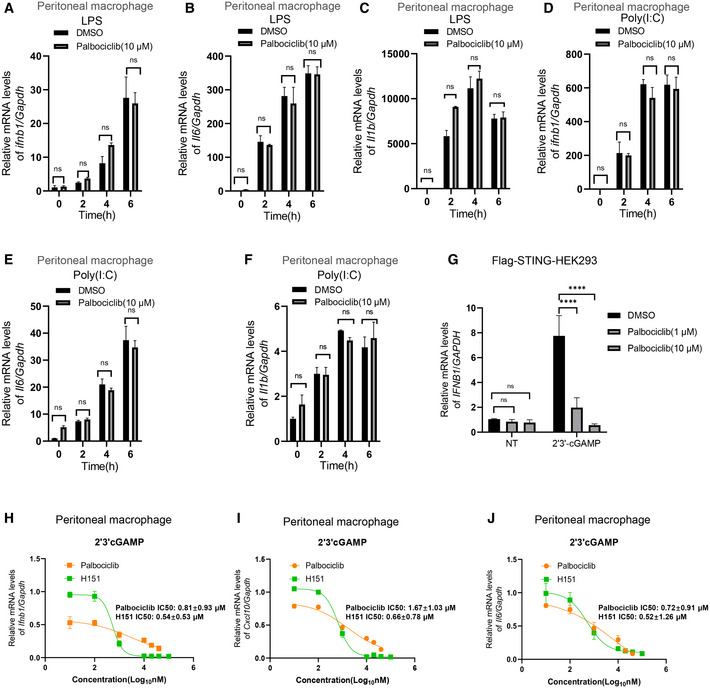

Specific inhibition of STING by Palbociclib is comparable to that of H151

We next checked whether Palbociclib specifically inhibited STING activation. Mouse peritoneal macrophages were treated with either lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or the dsRNA mimic Poly(I:C). Stimulation with either LPS or Poly(I:C) markedly induced the transcription of Ifnb1 and Il6 as well as Il1b (Fig 3A–F). However, treatment with Palbociclib did not have a significant effect on the induction of type I IFN or inflammatory cytokines (Fig 3A–F), indicating that Palbociclib may specifically inhibit STING activation. To further confirm the specificity of Palbociclib on the inhibition of STING activation, we stimulated Flag‐STING stably transfected HEK293 cells with cGAMP in the presence of an increasing dose of Palbociclib. Palbociclib inhibited STING‐mediated IFNB1 transcription in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig 3G), indicating that Palbociclib specifically inhibits STING signaling pathway.

Figure 3. Specific inhibition of STING activation by Palbociclib is comparable to that of H151.

-

A–FqRT‐PCR measurement of Ifnb1, Il6, and Il1b mRNA transcripts in mouse peritoneal macrophages left unstimulated or stimulated with LPS (0.1 μg/ml) (A–C) or transfected with Poly(I:C) (1 μg/ml) (D–F) in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM) for indicated times. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post‐hoc test. ns, not significant.

-

GqRT‐PCR measurement of IFNB1 transcripts in HEK293 cells stably expressing Flag‐STING that were left unstimulated or stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) for 4 h in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib at indicated concentrations. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post‐hoc test. ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

-

H–JFitted dose–response curves illustrating the relative level of the transcripts of Ifnb1 (H), Cxcl10 (I), and Il6 (J) in mouse peritoneal macrophages stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of Palbociclib and H151. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. The IC50 was calculated and shown.

We then compared the efficacy of the newly identified STING inhibitor Palbociclib with the existing STING covalent antagonist H151, which is one of the most potent inhibitors of STING (Haag et al, 2018; Tumurkhuu et al, 2020; Pan et al, 2021). Consistent with previous reports, H151 markedly reduced cGAMP‐induced transcription of Ifnb1, Cxcl10, and Il6 (Fig 3H–J). By titration of the concentration of the two compounds, the inhibitory effect of Palbociclib on cGAMP‐induced transcription of Ifnb1, Cxcl10, and Il6 was found to be comparable with that of H151 (Ifnb1: IC50 = 0.54 ± 0.53 μM for H151 and IC50 = 0.81 ± 0.93 μM for Palbociclib, P = 0.779; Cxcl10:IC50 = 0.66 ± 0.78 μM for H151 and IC50 = 1.67 ± 1.03 μM for Palbociclib, P = 0.698; and Il6: IC50 = 0.52 ± 1.26 μM for H151 and IC50 = 0.72 ± 0.91 μM for Palbociclib, P = 0.889; Fig 3H–J). Moreover, Palbociclib showed an advantage in inhibiting cGAMP‐induced STING activation over H151 when the concentrations of the compounds were low (Fig 3H–J). These data indicate that Palbociclib is a very promising STING inhibitor.

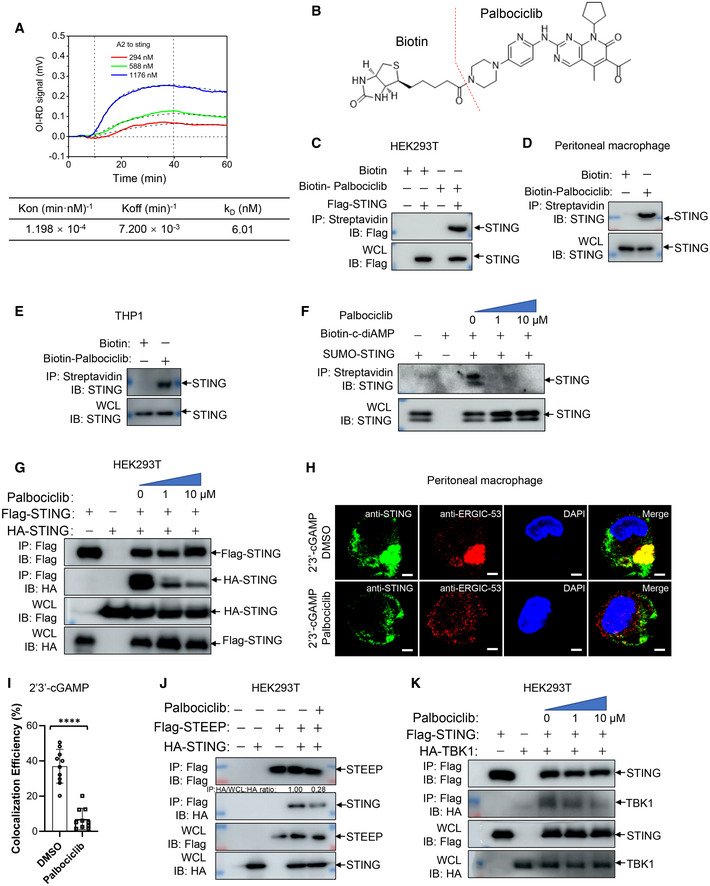

Palbociclib directly targets STING and impairs its activation

After identifying Palbociclib as a STING‐binding compound, we went on to confirm the interaction of Palbociclib with STING using a real‐time oblique‐incidence reflectivity difference (OI‐RD) assay. Palbociclib had a strong binding affinity to recombinant STING protein with a KD of 6.01 nM (Fig 4A), which was much stronger than the affinity of cGAMP to STING (K D = 543 nM) (Xie et al, 2020). We further generated biotin‐conjugated Palbociclib by linking biotin to the amidogen residue of Palbociclib (Fig 4B). An immunoprecipitation assay with streptavidin beads demonstrated an interaction of biotin‐Palbociclib with overexpressed Flag‐tagged STING in HEK293T cells (Fig 4C). We further detected the interaction of biotinylated‐Palbociclib with endogenous STING at the cellular level by immunoprecipitation with streptavidin beads and observed that biotin‐Palbociclib interacted with endogenous STING in both mouse peritoneal macrophages and THP1 cells (Fig 4D and E). As the engagement of STING by cGAMP results in its activation, we interrogated whether Palbociclib impairs STING activation by competitively inhibiting cGAMP binding. By using purified recombinant STING protein, we demonstrated an interaction of biotin‐c‐diAMP with STING, which was interrupted by the addition of Palbociclib (Fig 4F). These data indicate that Palbociclib may directly interact with STING and abrogate its interaction with a natural STING agonist. Notably, the dimerization of STING is a prerequisite for its activation (Barber, 2015; Gall et al, 2012; Lorenzo et al, 2018), though it has been reported that the STING dimer can be preformed in the ER (Dobbs et al, 2015; Georgana et al, 2018). Therefore, we checked whether Palbociclib affects STING dimerization. By transfecting HEK293T cells with Flag‐tagged and HA‐tagged STING in the absence or presence of Palbociclib, we found that Palbociclib markedly impaired the interaction of Flag‐STING with HA‐STING (Fig 4G). This indicates that the binding of Palbociclib with STING may abrogate its activation by impairing STING homodimerization.

Figure 4. Palbociclib directly targets STING and impairs its activation.

-

AA real‐time OR‐ID assay showing the association–dissociation curves of surface‐immobilized Palbociclib with recombinant STING protein. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

BStructure of synthesized biotin‐conjugated Palbociclib.

-

C–EImmunoblotting of the streptavidin precipitates of the mixture of biotin (100 μM) or biotin‐Palbociclib (100 μM) and the lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐STING (C), mouse peritoneal macrophages (D), and THP1 cells (E). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

FImmunoblotting of the streptavidin precipitates of the mixture of biotin‐c‐diAMP (2 μM) and recombinant SUNO‐tagged STING protein (10 μg/ml) in the presence of DMSO and increasing concentrations of Palbociclib (0, 1, 10 μM). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

GImmunoblotting of the lysates and anti‐Flag immunoprecipitates of HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐STING and HA‐STING in the presence of DMSO and indicated concentrations of Palbociclib. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

H, IRepresentative immunofluorescent assay of STING and ERGIC in mouse peritoneal macrophages stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) for 2 h in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM) (H). Scale bar, 25 μm. The quantification data are shown in (I). The data shown are mean ± SD from indicated number of cells from 1 representative of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. ****P < 0.0001.

-

JImmunoblotting of the lysates and anti‐Flag immunoprecipitates of HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐STEEP and HA‐STING in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

KImmunoblotting of the lysates and anti‐Flag immunoprecipitates of HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐STING and HA‐TBK1 in the presence of DMSO or indicated concentrations of Palbociclib. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Engagement of STING by CDNs results in its translocation from the ER to the ERGIC region, where it interacts with TBK1 and activated IRF3‐induced gene expression (Wang et al, 2014; Dobbs et al, 2015; Gui et al, 2019). The recruitment of TBK1 to STING by its C‐terminal tail (CTT) domain, and subsequent STING phosphorylation is essential for STING activation (Min et al, 2017; Nandakumar et al, 2019). An immunofluorescence assay of the cellular compartmentalization of STING demonstrated that cGAMP stimulation induced re‐localization of STING to the ERGIC region, which was significantly inhibited by the addition of Palbociclib (Fig 4H and I). The association of STING with STING ER exit protein (STEEP) has been demonstrated to be critical for inducing COPII‐mediated ER‐to‐Golgi trafficking of STING through stimulation of phosphatidylinositol‐3‐phosphate production and ER membrane curvature formation (Zhang et al, 2020a). Intriguingly, Palbociclib markedly reduced the interaction of STING with STEEP (Fig 4J), indicating that Palbociclib may block STING trafficking, at least partly, by interfering with the formation of the STING‐STEEP complex. We further checked whether Palbociclib modulates the formation of the STING‐TBK1 complex. By transfecting HEK293T cells with Flag‐STING and HA‐TBK1 in the absence or presence of increasing doses of Palbociclib, we demonstrated that Palbociclib markedly reduces the interaction of STING with TBK1 (Fig 4K). Taken together, Palbociclib directly binds STING with high affinity and impairs its dimerization, which may thereby affect multiple steps of STING activation including CDNs binding, STING trafficking, and STING‐TBK1 complex formation.

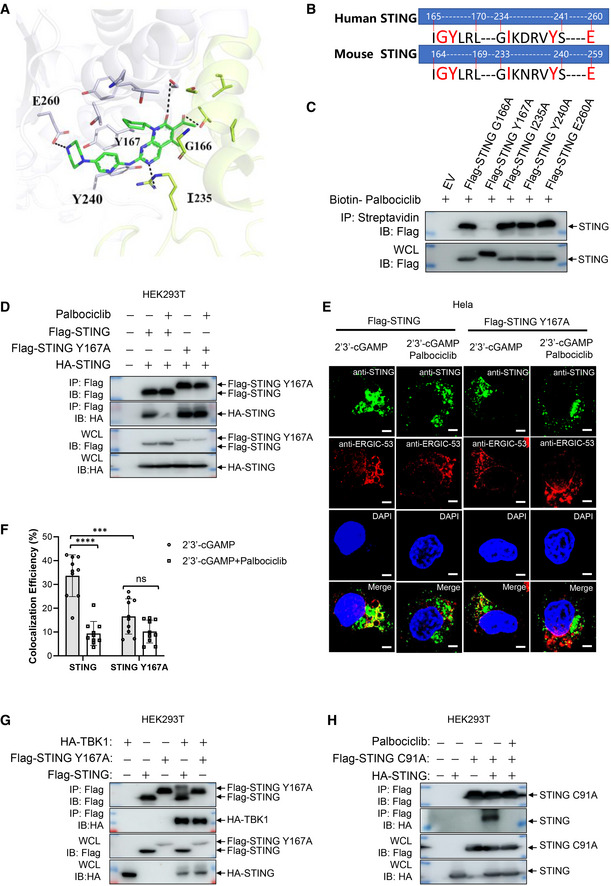

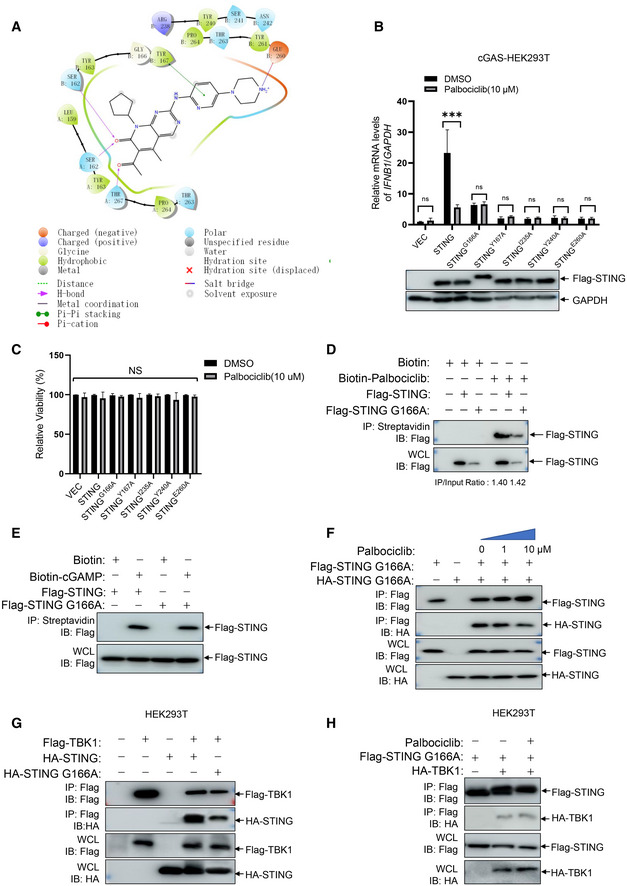

STING Y167 is critical for its interaction with Palbociclib and Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING

We then performed a molecular docking assay to analyze which amino acids of STING could be responsible for its interaction with Palbociclib. The crystal structure of human STING (PDB number: 6DNK) was used in the docking assay. The results indicated that G166, Y167, I235, Y240, and/or E260 of STING may be involved in its binding with Palbociclib (Figs 5A and EV3A). The alignment of the protein sequence of mouse and human STING indicated that these amino acids are evolutionarily conserved (Fig 5B). We, therefore, generated human STING mutants including STING G166A, STING Y167A, STING I235A, STING Y240A, and STING E260A. After generating human cGAS‐stably transfected HEK293 cells, we transfected these cells with Flag‐STING or its corresponding mutants for 48 h with or without 4 h of Palbociclib treatment and then measured IFNB1 transcripts. The results demonstrated that Palbociclib markedly reduced STING‐induced IFNB1 transcription (Fig EV3B). The mutation of STING Y167A, STING I235A, STING Y240A, and STING E260A almost completely impaired STING activation (Fig EV3B), indicating that these amino acids are required for STING activation. Notably, the levels of STING and its mutant protein expression were equal (Fig EV3B), and Palbociclib treatment for 4 h did not alter the viability of HEK293 cells transfected with various STING mutants (Fig EV3C), indicating that the reduced activity of STING G166A and other STING mutants was not caused by less protein expression or reduced cell viability. The mutation of STING G166 to alanine partly reduced STING activation, while Palbociclib did not show any further inhibitory effect on the activation of STING G166A, indicating that STING G166 may be involved in Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING (Fig EV3B). However, an immunoprecipitation assay with streptavidin beads demonstrated interaction of biotin‐Palbociclib with both overexpressed Flag‐tagged STING and Flag‐STING G166A in HEK293T cells (Fig EV3D), indicating that G166 is dispensable for the interaction of STING with Palbociclib. Moreover, an immunoprecipitation assay using streptavidin beads demonstrated comparable interaction of biotin‐cGAMP with overexpressed Flag‐STING and Flag‐STING G166A in HEK293T cells (Fig EV3E), indicating that G166 is not essential for the interaction of STING with cGAMP. This is in line with previous reports showing that G158, Y167, H232, and E260 are responsible for the binding of cGAMP with human STING (Shu et al, 2012; Diner et al, 2013; Zhang et al, 2013; Jeremiah et al, 2014). Moreover, an immunoprecipitation assay demonstrated that overexpressed HA‐STING G166A interacted with Flag‐STING G166A (Fig EV3F), indicating that G166 is not critical for the dimerization of STING. Notably, Palbociclib still markedly reduced the interaction of HA‐STING G166A with Flag‐STING G166A (Fig EV3F), indicating that G166 of STING is not responsible for Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING dimerization. We further interrogated whether G166 is involved in Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of the STING‐TBK1 complex formation. Using HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐TBK1 and HA‐STING or HA‐STING G166A, we demonstrated by immunoprecipitation assays that the mutation of G166 largely reduced its interaction with TBK1 (Fig EV3G). However, Palbociclib did not further reduce the interaction of TBK1 with STING G166A (Fig EV3H). These data indicate that Palbociclib may inhibit STING activation partly by interfering with STING‐TBK1 complex formation via G166.

Figure 5. STING Y167 is critical for its interaction with Palbociclib and Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING.

-

AMolecular docking assay showing the interaction of Palbociclib with STING. Key amino acids responsible for the interaction were indicated.

-

BAlignment of the protein sequence of mouse and human STING were performed and the evolutionarily conserved amino acids were indicated.

-

CImmunoblotting of the streptavidin precipitates of the mixture of biotin‐Palbociclib (100 μM) and the lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with corresponding Flag‐STING mutants. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

DImmunoblotting of the lysates and anti‐Flag immunoprecipitates of HEK293T cells transfected with HA‐STING and Flag‐STING or Flag‐STING Y167A in the presence of DMSO and Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

E, FRepresentative immunofluorescent assay of STING and ERGIC in HeLa cells stimulated with 2'3' cGAMP (0.1 μg/ml) for 2 h in the presence of DMSO or Palbociclib (10 μM) (E). Scale bars, 25 μm. The quantification data are shown in (F). The data shown are mean ± SD from indicated number of cells from 1 representative of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

-

GImmunoblotting of the lysates and anti‐Flag immunoprecipitates of HEK293T cells transfected with HA‐TBK1 and Flag‐STING or Flag‐STING Y167A. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

-

HImmunoblotting of the lysates and anti‐Flag immunoprecipitates of HEK293T cells transfected with HA‐STING and Flag‐STING C91A in the presence of DMSO and Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV3. G166 of STING is required for Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of the formation of STING‐TBK1 complex.

- Molecular docking assay showing the interaction of Palbociclib with STING. Key amino acids responsible for the interaction were indicated.

- qRT‐PCR measurement of IFNB1 transcripts in Flag‐cGAS stably transfected HEK293 cells that had been transfected with empty vector (VEC), wild‐type STING and corresponding STING mutants in the presence of DMSO and Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post‐hoc test. ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant. The lower panel of immunoblotting is representative of n = 3 independent experiments.

- MTS detection of the viability of Flag‐cGAS‐HEK293 cells transfected with empty vector (VEC), wild‐type STING, and corresponding STING mutants in the presence of DMSO and Palbociclib (10 μM) for 4 h. Statistical significance was determined by one‐way ANOVA. ns, not significant.

- Immunoblotting of the streptavidin precipitates of the mixture of biotin or biotin‐Palbociclib (10 μM) and the lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐STING or Flag‐STING G166A. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

- Immunoblotting of the streptavidin precipitates of the mixture of biotin or biotin‐cGAMP (10 μM) and the lysates of HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐STING or Flag‐STING G166A. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

- Immunoblotting of the lysates and anti‐Flag immunoprecipitates of HEK293TT cells transfected with HA‐STING G166A and Flag‐STING G166A in the presence of DMSO and indicated concentrations of Palbociclib. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

- Immunoblotting of the lysates and anti‐Flag immunoprecipitates of HEK293T cells transfected with Flag‐TBK1 and HA‐STING or HA‐STING G166A. The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

- Immunoblotting of the lysates and anti‐Flag immunoprecipitates of HEK293T cells transfected with HA‐TBK1 and Flag‐STING G166A in the presence of DMSO and Palbociclib (10 μM). The data shown are representative of n = 3 biological replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

To further clarify the mechanisms underlying Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING, we mapped the amino acids of STING responsible for its interaction with Palbociclib. An immunoprecipitation assay using streptavidin beads revealed that interaction with biotin‐Palbociclib was almost completely abrogated in the STING Y167A mutant (Fig 5C), indicating that Y167 is essential for Palbociclib binding. Therefore, we further interrogated the role of Y167 of STING in Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING. Intriguingly, the addition of Palbociclib markedly reduced the interaction of HA‐STING with Flag‐STING but not Flag‐STING Y167A (Fig 5D), indicating that Y167 is essential for Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING dimerization. Notably, it has been demonstrated that Y167 is required for CDN binding (Shang et al, 2012), indicating that Palbociclib may impede the binding of CDN to STING by competitive binding or by abrogating its dimerization. Strikingly, trafficking of overexpressed Flag‐STING Y167A to the ERGIC in response to cGAMP stimulation was much attenuated compared to that of Flag‐STING (Fig 5E). Importantly, Palbociclib markedly reduced the re‐localization of Flag‐STING but not Flag‐STING Y167A to the ERGIC (Fig 5E and F). These data indicate that Palbociclib may inhibit STING trafficking by targeting Y167 of STING. Unexpectedly, though STING G166A was required for its interaction with TBK1 (Fig EV3G), the mutation of Y167 did not significantly affect the interaction of overexpressed STING with TBK1 (Fig 5G), indicating that Y167 is not required for the formation of the STING‐TBK1 complex. Notably, the only major STING inhibitor described to date is H151, which covalently blocks palmitoylation of STING at C91, thereby impairing its assembly into multimeric complexes at the Golgi apparatus, which, in turn, inhibits the recruitment of downstream signaling factors (Haag et al, 2018). Our data showed that the mutation of STING C91 to alanine still interacted with wild‐type STING, which was largely impaired by the addition of Palbociclib (Fig 5H). These data indicate that Palbociclib may inhibit STING activation by a distinct mechanism, targeting Y167 of STING to block its homodimerization, which is independent of palmitoylation of STING C91.

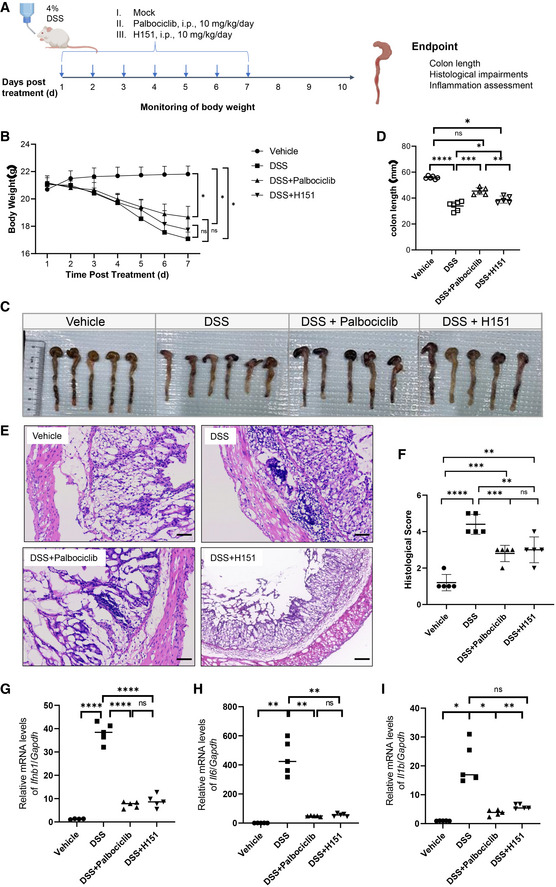

Palbociclib alleviates DSS‐induced colitis by reducing inflammation

It has been previously demonstrated that STING activation is critical for DSS‐induced colitis in the mouse model, and that STING inhibitors such as H151 protect against DSS‐induced colitis by reducing hyperinflammation (Gao et al, 2015; Martin et al, 2019). We, therefore, set up a DSS‐induced colitis model in mice and examined the effect of Palbociclib on the progression of disease (Fig 6A). The treatment with DSS led to substantial body weight loss, and administration with Palbociclib or H151 partly reversed the trend to reduced body weight (Fig 6B). Moreover, DSS treatment markedly reduced the colon length, with both Palbociclib and H151 significantly preventing this reduction (Fig 6C and D). H&E staining of the colon tissue revealed that DSS treatment markedly increased epithelial damage and crypt cell losses, while colonic damage was markedly reduced in mice treated with either Palbociclib or H151 (Fig 6E and F). We then harvested the colon tissue and measured the abundance of downstream effectors of STING by measuring the transcripts of Ifnb1, Il6, and Il1b. DSS treatment strongly induced the transcription of these genes, while the treatment with Palbociclib or H151 almost abrogated the response (Fig 6G–I), indicating a critical role of Palbociclib‐mediated resolution of inflammation in its protective effects against DSS‐induced colitis.

Figure 6. Palbociclib alleviates DSS‐induced colitis by reducing inflammation.

-

ADiagram showing the experimental procedure for the evaluation of the effect of Palbociclib and H151 on DSS‐induced colitis in mice.

-

BThe weight of mice left untreated or treated with DSS in the absence or presence of H151 or Palbociclib. Statistical significance between data sets was assessed by one‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post‐hoc test between all groups. Values are means ± SEM, n = 5 mice per group with differences denoted by *P < 0.05; ns, not significant.

-

C, DThe representative image of colon tissue harvested from mice of indicated groups is shown in (C). The length of colon is analyzed in (D). Statistical significance between data sets was assessed by one‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post‐hoc test between all groups. Values are means ± SEM, n = 5 mice per group with differences denoted by *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

-

E, FRepresentative H&E staining of the histological changes in colon tissues harvested from mice of indicated groups (E). Scale bar, 200 μm. The quantification of histological score was shown in (F). Mann–Whitney U‐test was used for statistical analysis of two independent groups. Values represent means ± SEM, each symbol indicates the value of one mouse from n = 5 mice per group. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

-

G–IqRT‐PCR measurement of transcripts of Ifnb1 (G), Il6 (H), and Il1b (I) in mouse colon tissues harvested from mice of indicated groups. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 5 mice from one of three biological replicates with similar results. Each symbol indicates the value of one mouse from n = 5 mice per group. Statistical significance was determined by one‐way ANOVA test, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post‐hoc test between all groups. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Source data are available online for this figure.

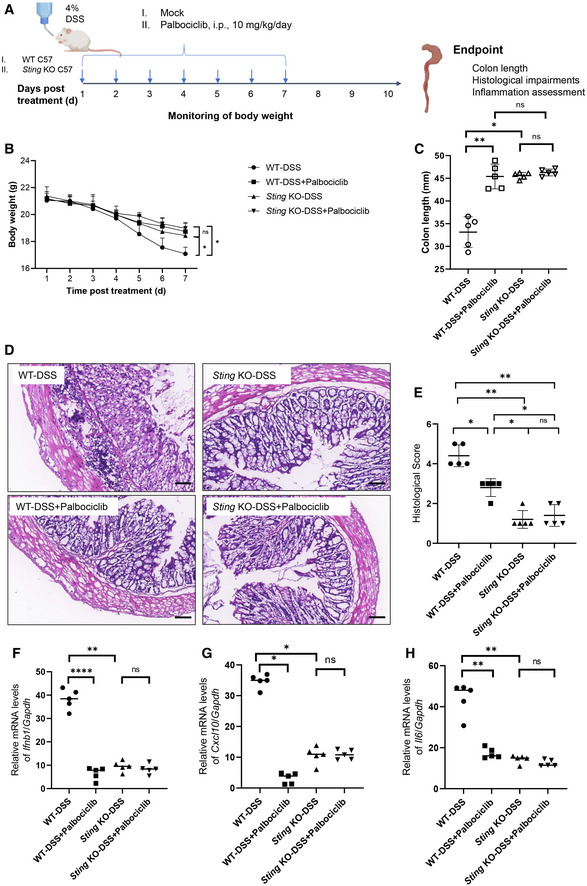

To confirm that the protective effect of Palbociclib in vivo was STING specific, we next investigated the effect of Palbociclib on DSS‐induced colitis in Sting knockout mice (Fig EV4A). Administration of Palbociclib or deletion of Sting both partially reversed the trend to reduction in body weights caused by treatment with DSS (Fig EV4B). Moreover, the genetic ablation of Sting markedly abrogated the reduction in colon length caused by DSS treatment (Fig EV4C). Importantly, Palbociclib markedly reversed the reduction in colon length in DSS‐treated WT mice rather than Sting knockout mice (Fig EV4C), suggesting that Palbociclib may act largely through STING. Consistent with this, Palbociclib markedly attenuated DSS‐induced colon tissue damage in WT but not Sting knockout mice, as demonstrated by H&E staining (Fig EV4D and E). The measurement of the abundance of transcripts of STING downstream effectors including Ifnb1, Il6, and Il1b demonstrated that the deletion of Sting dramatically impaired this response (Fig EV4F–H). Importantly, Palbociclib markedly inhibited the transcription of these genes in WT mice rather than Sting knockout mice post DSS treatment. Taken together, the data demonstrate that the in vivo protective effect of Palbociclib on DSS‐induced colitis is dependent on STING.

Figure EV4. Palbociclib protects DSS‐induced colitis in STING‐dependent manner.

-

ADiagram showing the experimental procedure for the evaluation of the effect of Palbociclib on DSS‐induced colitis in wild‐type and Sting knockout mice.

-

BThe body weight of wild‐type and Sting knockout mice treated with DSS in the absence or presence of Palbociclib. Statistical significance between data sets was assessed by one‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post‐hoc test between all groups. Values are means ± SEM, n = 5 mice per group with differences denoted by *P < 0.05; ns, not significant.

-

CThe length of colon of wild‐type and Sting knockout mice treated with DSS in the absence or presence of Palbociclib. Statistical significance between data sets was assessed by one‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post‐hoc test between all groups. Values are means ± SEM, n = 5 mice per group with differences denoted by *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

-

D, ERepresentative H&E staining of the histological changes in colon tissues harvested from mice of indicated groups (D). Scale bar, 200 μm. The quantification of histological score was shown in (E). Mann–Whitney U‐test was used for statistical analysis of two independent groups. Values represent means ± SEM, each symbol indicates the value of one mouse from n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

-

F–HqRT‐PCR measurement of transcripts of Ifnb1 (F), Cxcl10 (G), and Il1b (H) in mouse colon tissues harvested from mice of indicated groups. The data shown are mean ± SEM; each symbol indicates the value of one mouse from n = 5 mice per group. Statistical significance was determined by one‐way ANOVA test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Source data are available online for this figure.

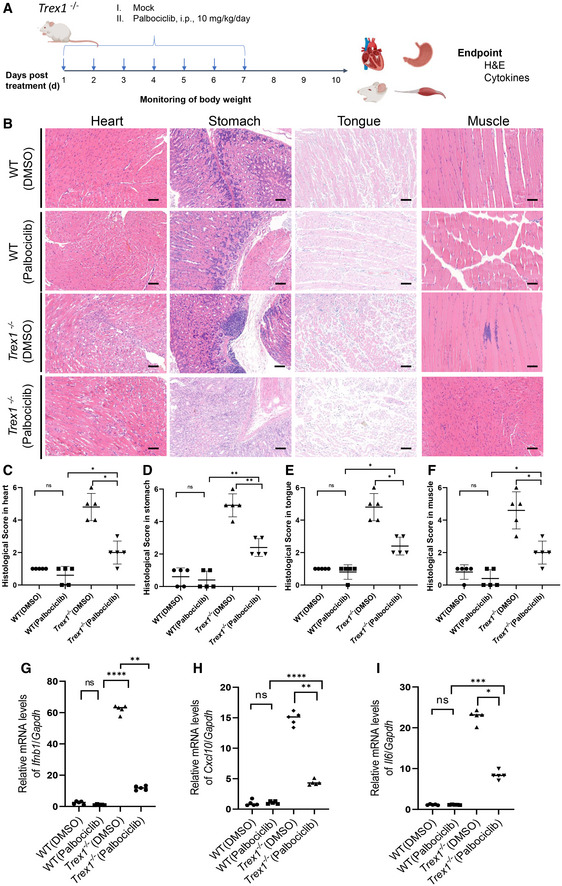

Palbociclib ameliorates autoinflammatory disease caused by genetic ablation of Trex1 in mice

To further validate the in vivo protective effect of Palbociclib in STING‐related diseases, we employed Trex1 −/− mice, which develop STING‐dependent autoinflammation (Gall et al, 2012). Trex1 −/− mice were treated with vehicle or Palbociclib (10 mg/kg per day, i.p.) for 7 days and were then left to rest for another 3 days. The mice were then sacrificed and tissues including heart, stomach, tongue, and thigh muscles were collected for further analysis (Fig 7A). H&E staining of the tissues revealed that the deficiency of Trex1 resulted in dramatic tissue damage, which was markedly attenuated by the administration of Palbociclib (Fig 7B–F). Moreover, the deletion of Trex1 resulted in dramatic elevation of the transcripts of Ifnb1, Cxcl10, and Il6 in the stomach, and Palbociclib treatment markedly reduced this response (Fig 7G–I). These data demonstrate that Palbociclib protects against STING‐driven hyperinflammation and pathological damage in Trex1 −/− mice, providing additional evidence that the in vivo effect of Palbociclib is STING specific.

Figure 7. Palbociclib ameliorates autoinflammatory disease caused by Trex1 deficiency.

-

ADiagram showing the experimental procedure for the evaluation of the effect of Palbociclib on the autoinflammatory disease in Trex1 −/− mice.

-

B–FRepresentative H&E staining of the histological changes in heart, stomach, tongue, and thigh muscle tissues harvested from mice of indicated groups (B). Scale bar, 200 μm. The quantification of histological score was shown in (C‐F). Mann–Whitney U‐test was used for statistical analysis of two independent groups. Values represent means ± SEM; each symbol indicates the value of one mouse from n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

-

G‐IqRT‐PCR measurement of transcripts of Ifnb1 (G), Cxcl10 (H), and Il6 (I) in mouse stomach tissues harvested from mice of indicated groups. The data shown are mean ± SEM of n = 5 mice from one of three biological replicates with similar results. Each symbol indicates the value of one mouse from n = 5 mice per group. Statistical significance was determined by one‐way ANOVA test, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post‐hoc test between all groups. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Discussion

The innate immune receptor STING has been an appealing therapeutic target for multiple diseases, including cancer, inflammatory diseases, and autoimmune diseases. In this study, we employed an advanced high‐throughput screening method based on the interactions of our target protein, STING, with small‐molecule chemicals, and successfully identified Palbociclib, an FDA‐approved orally available CDK inhibitor, as a novel non‐nucleotide‐based STING inhibitor that blocks the homodimerization of STING. Importantly, Palbociclib showed high protective efficacy against autoinflammatory diseases caused by chemical insults or genetic ablation of Trex1 in mice, in a STING‐dependent manner. Our findings provide a basis for the repurposing of Palbociclib and its analogs for clinical therapy of STING‐driven autoimmune diseases, although the potential toxicity and side effects of long‐term CDK inhibition should be evaluated.

Multiple strategies have been employed to screen STING modulators. Luciferase reporter assays have been used to conduct high‐throughput screening based on the activation of the type I IFN response in a STING‐dependent manner (Sali et al, 2015; Gall et al, 2018; Haag et al, 2018). An automated ligand identification system is used to identify STING modulators, utilizing 2:1 binding stoichiometry to offset the challenges of a large binding pocket, and thus effectively competing with cGAMP (Siu et al, 2018). Here, we performed a small‐molecule microarray‐based screening by optical biosensing of molecular interactions, which has been successfully applied for the identification of autophagosome‐tethering compound (ATTEC), which lowers levels of disease‐causing proteins such as mutant huntingtin protein (mHTT), in our previous study (Li et al, 2019). We printed 3,375 compounds in duplicate onto a microarray on isocyanate‐functionalized glass slides using the nucleophile‐isocyanate reaction, which forms covalent bond between the compounds and the glass slides. The screening platform was unlabeled and therefore avoided fluorescence defects. Moreover, the optical biosensing platform showed great advantages in the real‐time in situ detection of reaction end points, with rapid high‐throughput processing (Zhu et al, 2016). In addition, the native probe structure and function were preserved, making the screening suitable for determining probe function or quantifying the physicochemical properties of the probe (e.g. binding affinity or reaction rates) (Fei et al, 2010). In this study, we successfully identified functional compounds targeting STING by using recombinant STING protein. This further demonstrated the power of this platform in screening small molecules targeting proteins of interest and also paved the way for screening compounds targeting other key signaling proteins such as cGAS.

Cyclin‐dependent kinases (CDKs) are a family of serine/threonine kinases, originally identified due to their role in the regulation of the cell cycle. CDKs form complexes with the cyclin family of proteins, which are characterized by dramatic shifts in abundance depending on the stage of the cell cycle. Because of their role in cell cycle progression and their deregulation in various cancers, CDKs have been attractive targets for drug development. Two CDK inhibitors, Palbociclib and Ribociclib, have recently been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of advanced breast cancer (Finn et al, 2015; Dickler et al, 2016). Milciclib reached the primary end points in two multicenter clinical trials of phase 2 thymic carcinoma and thymoma (CDKO‐125A‐006: 72 patients, CDKO‐125A‐007: 30 patients). In our study, we have identified STING as a novel target of Palbociclib. It has been well documented that STING plays a crucial role in promoting anti‐tumor immunity by activating innate immunity, boosting DC maturation (Curran et al, 2016) and activating natural killer cells (Nicolai et al, 2020; preprint: Steiner et al, 2020) as well as CD8+ T cells (Sen et al, 2019). It is, therefore, highly likely that CDKi‐mediated inhibition of STING activation may impair STING‐mediated anti‐tumor immunity, which will bring attention to potential drawbacks in the clinical application of Palbociclib and its structural analogs in cancer therapy.

Though CDKs have been linked to the regulation of inflammatory pathways (Jeremiah et al, 2014) and CDK activity is critical for the translational control of IFN‐β (Cingz & Goff, 2018), our work demonstrates that the inhibition of IFNB1 transcription caused by Palbociclib is dependent on its structure rather than its inhibitory effect on CDK activity. Intriguingly, Palbociclib inhibited STING activation independently of its canonical targets CDK4/6. Mechanistically, Palbociclib directly interacted with STING, and Y167 was critical for mediating the interaction. Moreover, our work demonstrated that Palbociclib inhibited the dimerization of STING, which has been reported to be essential for STING activation (Barber, 2015; Gall et al, 2012; Lorenzo et al, 2018). Notably, Y167 is required for Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING dimerization, as well as STING trafficking. Our findings indicate that Palbociclib may function by a distinct mechanism, directly targeting Y167 of STING and blocking its homodimerization, which thereby terminates its cGAMP binding capability, trafficking, and final activation. Since Y167 is required for CDN binding (Shang et al, 2012), it remains possible that Palbociclib targets Y167 to competitively hinder CDN binding. It has been demonstrated that the CTT domain of STING mediates its direct interaction with TBK1 (Zhang et al, 2019). Our data demonstrate that G166 is also critical for the formation of STING‐TBK1 complex. Moreover, targeting STING with Palbociclib interrupts the formation of the complex of TBK1 with STING rather than STING G166A, indicating that G166 may be critical for Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of the STING‐TBK1 interaction. It has been reported that post‐translational modifications such as ubiquitination are involved in the regulation of the association of STING with TBK1 (Wang et al, 2014). Whether the G166 residue of STING is responsible for the recruitment of factors regulating the post‐translational modifications of STING which thereby indirectly affect its interaction with TBK1 warrants further investigations.

Increasing evidence has linked STING overactivation to multiple autoimmune diseases, including SLE, AGD, and SAVI (Liu et al, 2014; Dobbs et al, 2015). STING activation also plays a role in the development and exacerbation of DSS‐induced colitis (Martin et al, 2019; Hu et al, 2021). The development of STING inhibitors is an area of active investigation, particularly for the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Of note, Palbociclib has been demonstrated to ameliorate rodent arthritis in experimental arthritis models (Taniguchi et al, 1999; Nasu et al, 2000), possibly functioning through inhibition of proliferation of synovial fibroblasts and exerting anti‐inflammatory effects in CDK activity‐dependent and ‐independent manners (Sekine et al, 2008; Nonomura et al, 2014). Our work demonstrates that Palbociclib attenuates DSS‐induced pathological impairments and inflammation in the gut in a STING‐dependent manner. Moreover, Palbociclib marked reduces the pathological features and autoinflammation caused by the genetic ablation of Trex1, which induces STING‐dependent autoinflammatory disease (Gall et al, 2012). We, herein, identify Palbociclib as a novel pharmacological STING antagonist which can attenuate autoimmune disease features caused by chemical insults or genetic ablation of Trex1 in mice.

With increasing attention to the significance of the type I IFN signaling pathway in autoimmune diseases, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and small‐molecule inhibitors have been designed to target the type I IFN signaling pathway, including IFN‐α or IFNARs, Toll‐like receptors, and their downstream pathways, for the treatment of autoimmune disorders. Clinical trials using these treatments have already produced positive results. The JAK inhibitors tofacitinib and baricitinib have been approved by the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA; Taylor, 2019). A mAb against IFNAR, anifrolumab (formerly MEDI‐546), has completed phase III clinical trials in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and has shown excellent efficacy and safety profiles (Morand et al, 2020). The JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor baricitinib has also entered phase III trials for the treatment of SLE (Kubo et al, 2019). Notably, many drugs applied for the therapy of autoimmune diseases are repurposed from cancer chemotherapeutic regimens which are potentially toxic for long‐term treatment (Koźmiński et al, 2020; Xu et al, 2021). To minimize the side effects arising from the toxicity of those drugs, repeated low‐dose application is an option for the treatment of autoimmune patients (Ferrara et al, 2018; Kerschbaumer et al, 2020). Since a STING‐targeting drug is currently unavailable, repurposing an FDA‐approved drug could lead to the rapid development of approved clinical treatments for diseases precipitating from constitutive STING activation. Thus, clinical studies on the safety and efficacy of Palbociclib or structurally related drugs in the therapy of STING‐driven autoimmune diseases are needed.

In summary, our study has revealed STING to be a novel direct target protein of the CDK inhibitor Palbociclib and uncovered a unique inhibitory mechanism by which Palbociclib blocks the homodimerization of STING. The protective effects of Palbociclib against the autoinflammatory disease caused by DSS treatment or genetic ablation of Trex1 suggest its potential application in the clinical therapy of STING‐associated autoimmune diseases (Fig EV5). Our work will also provide the basis for the design and development of novel STING inhibitors based on the structure of Palbociclib that avoid the potential toxicity resulting from inhibition of CDK activity.

Figure EV5. Diagram showing the identification of Palbociclib as a novel pharmacological inhibitor of STING using a distinct mechanism by targeting Y167 of STING to block its homodimerization.

High‐throughput screening approach based on the interaction of small‐molecule chemical compounds with recombinant protein successfully identified functional STING modulators. The cyclin‐dependent protein kinase (CDK) inhibitor Palbociclib directly targets STING Y167 and inhibits its homodimerization and subsequent activation. Moreover, STING G166 is critical for Palbociclib‐mediated inhibition of STING‐TBK1 complex formation. Palbociclib thereby serves as a potential therapy of STING‐related autoinflammatory diseases caused by DSS treatment or genetic ablation of Trex1. The images in Figs 1B and C, 5A, and 7A and B are shown repeatedly in the diagram to summarize the flowchart and major findings of the study.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Palbociclib (HY‐50767), H151(HY‐112693), Flavopiridol (HY‐10005), Bohemine (HY‐12843), Alsterpaullone (HY‐108359), Purvalanol (HY‐18299A), Istradefylline (HY‐10888), WHI‐P154 (HY‐13895), Esmolol hydrochloride (HY‐B1392), Salubrinal (HY‐15486), Ibuprofen (HY‐78131), Famotidine (HY‐B0377), Acacetin (HY‐N0451), Valdecoxib (HY‐15762), Phenazopyridine hydrochloride (HY‐B0985), Moguisteine (HY‐B0505), Caspofungin Acetate (HY‐17006), Diclazuril (HY‐B0357), BMS‐378806(HY‐14134), Intepirdine (HY‐14339), Dichlorphenamide (HY‐B0397), Proflavine hemisulfate (HY‐B0883), Azilsartan (HY‐14914), Rapamycin (HY‐10219), and Chloroquine (HY‐17589A) were obtained from MedChemExpress (Shanghai, China). Recombinant STING protein (#CR43) was obtained from Novoprotein (Shanghai, China). Antibodies including anti‐STING (#13647), anti‐phospho‐TBK1 (#5483), anti‐GAPDH (#5174), anti‐phospho‐IRF3 (#37829), anti‐phospho‐NF‐κB p65 (#3033), anti‐LC3B (#3868), anti‐CDK4(#12790), and anti‐CDK6(#13331) were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, USA) and were used at a dilution of 1:1,000 for western blot assays. Goat Anti‐Mouse IgG H&L (HRP) (ab6789) and Goat Anti‐Rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (ab6721) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, British). Anti‐ERGIC (E1031) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis Missouri, America). 2’3’cGAMP (#tlrl‐nacga23‐1), 2’2’cGAMP (#tlrl‐nacga22‐1), and c‐di‐AMP (#tlrl‐nacda‐5) were purchased from InvivoGen (California, USA). Biotin‐cGAMP (#C161) and 8‐Biotin‐AET‐c‐diAMP (#B156) were purchased from BioLog Institute (Berlin, Germany).

STING plasmids were generated as previous report (Liu et al, 2019). STINGC91A, STINGG166A, STING Y167A, STING I235A, STING Y240A, and STING E260A mutant plasmids were generated by site‐directed mutagenesis at Youbio Biotechnology Company (Changsha, China). The primers are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The sequence of primers for site‐directed mutagenesis.

| Plasmids | Primers |

|---|---|

| Flag‐STINGC91A | F: CCTGCCTGGGCGCCCCCCTCCGCCGTGGGG |

| R: GAGGGGGGCGCCCAGGCAGGCCCGCAC | |

| Flag‐STINGG166A | F: ACATCGCATATCTGCGGCTGATCCTGC |

| R: CAGCCGCAGATATGCGATGTAATATGACCATGCCAG | |

| Flag‐STINGY167A | F: GGGCTGGCATGGTCATATTACATCGGAGCCCTGCGGCTGATCCTGCCA |

| R: GATGTAATATGACCATGCCAGCC | |

| Flag‐STINGI235A | F: AGCAACAGCATCTATGAGCTT |

| R: AGAAGCTCATAGATGCTGTTGCTGTAAACCCGATCCTTGGCGCCAGCATGGTCACCGG | |

| Flag‐STING Y240A | F: AGCAACAGCATCTATGAGCTT |

| R: AGCTCATAGATGCTGTTGCTGGCAACCCGATCCTTGATGCCA | |

| Flag‐STING E260A | F: ACCCCCTTGCAGACTTTGTT |

| R: CAAACAAAGTCTGCAAGGGGGTGGCGTACGCCAGGACACAGGTGCCCG |

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center, CAS, China. C57BL/6J‐Sting1 gt /J (Common Name: Goldenticket [Gt]) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) (Strain number: #017537). Trex1 +/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. Bo Zhong from Wuhan University (Zhang et al, 2020b). Trex1 −/− mice were generated by further mating the male and female Trex1 +/− mice and were genotyped by standard PCR. Male mice (8–10 weeks of age) were fed standard laboratory chow, allowed water ad libitum, and were housed in a double barrier unit within individual micro‐isolator cages (Techniplast) having HEPA filter lids with individual filtered air and water supplies in a room maintained at 22 ± 1°C, 65–75% humidity, and a 12 h light/dark cycle.

Evaluation of the protective effect of Palbociclib on autoimmune diseases in mice induced by DSS treatment or genetic ablation of Trex1

Male C57BL/6 mice were selected for the DSS‐induced colitis mouse model as they are generally considered more susceptible than females to DSS (increased severity and increased hyperplasia) (Mähler et al, 1998). Male C57BL/6 mice and Sting knockout mice were administered 4% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in their drinking water for 7 days. The other two groups were treated with 10 mg/kg/day i.p of H151 or Palbociclib, concomitant with DSS treatment.

To detect the in vivo efficacy of Palbociclib in Trex1 −/− mice, male C57BL/6 mice and Trex1 −/− mice (6‐week‐old) were injected intraperitoneally with Palbociclib (10 mg/kg) or vehicle (corn oil, 10 mg/kg) daily for 1 week. Mice were monitored daily to assess changes in body weight. Mice were kept under specific pathogen‐free (SPF) conditions in the animal facility at Tongji University, China. All animal experiments were performed according to institutional guidelines approved by the ethics committees of Tongji University School of Medicine.

Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney epithelial cells (HEK293T; ATCC CRL‐11268) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; HyClone) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 100 U ml–1 penicillin and streptomycin. Macrophages, human leukemia monocytic cells (THP1; ATCC TIB‐202) and Henrietta Lacks cells (HeLa; ATCC CCL2) were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS. Peritoneal macrophages were obtained from mice 3 days after injection of thioglycollate (Becton, Dickinson & Company). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated using gradient centrifugation in Ficoll‐Paque solution (Pharmacia) (Boyum 1968). Isolated PBMC were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 50‐μM 2‐mercaptoethanol and antibiotics (RPMI‐10 Sigma) at microtitration desks in concentrations 106 cells per well. Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination, and only those cells that were tested negative were used for further studies.

The CDK4/6 knockout THP1 cells were generated by the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR‐associated protein‐9 (Cas9) system (Liu et al, 2019). HEK293T cells were transfected by means of Lipofectamine 3000 with pSPAX2, pMD2.G, and LentiCRISPRv2 containing a guide RNA (gRNA) that targeted human CDK4 (TGAAATTGGTGTCGGTGCCT). Lentiviruses were collected 48 h later and were applied to infect THP1 cells. Subsequently, selection of CDK4 KO cells with puromycin (1 μg/ml) was carried out. The process was then repeated with another gRNA(pSpCas9(BB)‐2A‐GFP) targeting human CDK6 (ACAGAGCACCCGAAGTCTTG). Subsequently, CDK4/6 KO cells were screened by cell sorting. Finally, clones derived from single CDK4/6 KO cells were obtained by serial dilutions in a 96‐well‐plate and were confirmed by western blotting.

All cell lines used tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

Preparation of ISD

Non‐phosphorylated oligodeoxynucleotides were purchased from TsingKe (Beijing. China) and full‐length content was verified by separation of an aliquot on urea‐containing 10% polyacrylamide gels, followed by ultraviolet shadowing. Fully complementary strands were annealed at 200 μM strand concentration in buffer containing 20 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, and 150 mM NaCl by first incubating at 95°C for 90 s, followed by slow cooling to 25°C at a rate of 0.1°C per second in a Peltier thermocycler (Bio‐Rad). Complete annealing was verified by electrophoresis using 2.5% low melting temperature agarose gel (Life Technologies, 15517‐014) containing ethidium bromide and comparing the mobility with the single‐stranded oligodeoxynucleotides. The sequences used for annealing are ISD_F: TACAGATCTACTAGTGATCTATGACTGATCTGTACATGATCTACA; ISD_R: TGTAGATCATGTACAGATCAGTCATAGATCACTAGTAGATCTGTA.

Preparation of the small‐molecule microarrays

Small‐molecule microarrays (SMM) containing 3,375 bioactive compounds were used for high‐throughput screening of target proteins. The compound library containing 1,527 drugs approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 1 053 natural products from traditional Chinese medicine, and 795 known inhibitors were printed onto the SMMs. Each compound was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 10 μM and printed in duplicates in a vertical direction on homemade phenyl isocyanate functionalized glass slides with a contact microarray printer (SmartArrayer 136, CapitalBio Corporation). Biotin‐BSA at a concentration of 7 600 nM in 1× phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and biotin‐(PEG)2‐NH2 at a concentration of 5 μM in DMSO were printed at the inner and outer borders of SMMs, respectively. The diameter of each spot was about 150 μm and spacing between two adjacent spots was 250 μm. The printed SMMs were then dried at 45°C for 24 h to facilitate covalent bonding of nucleophilic groups of small molecules to isocyanate groups of the functionalized slides. Afterward, the SMMs were stored in a −20°C freezer.

Compound–protein interaction measurements by oblique‐incidence reflectivity difference (OI‐RD) microscopy

For high‐throughput preliminary screening of target proteins, a SMM was assembled into a fluidic cartridge and washed in situ with a flow of 1× PBS to remove excess unbound small molecules. After washing, the SMM was scanned with a label‐free OI‐RD scanning microscope to image small molecules immobilized on glass slides. After blocking with 7,600 nM BSA in 1× PBS for 30 min, the SMM was incubated with the target protein for 2 h. Recombinant STING protein (#CR43) at a concentration of 60 nM was screened on separate fresh SMMs. OI‐RD images were scanned for each operation, including washing, blocking, and incubation. The OI‐RD difference images (images after incubation‐images before incubation) were used for analysis, and vertical bright doublet spots indicated compounds that bind with target proteins in both replicates.

Real‐time Palbociclib‐STING interaction measurement by OI‐RD microscopy

To measure the binding kinetics of target proteins with compounds, we prepared new SMMs consisting of Palbociclib. Three identical microarrays were printed on one glass slide and Palbociclib was printed in triplicates in a single microarray. The printed small SMMs were assembled into a fluidic cartridge with each microarray housed in a separate chamber. Before the binding reaction, the slide was washed in situ with a flow of 1× PBS to remove excess unbound samples, followed by blocking with 7,600 nM BSA in 1× PBS for 30 min. For the binding kinetics measurement, 1× PBS was first flowed through a reaction chamber at a flow rate of 0.01 ml min−1 for 5 min to acquire the baseline. 1× PBS was then quickly replaced with the probe solution of the target protein at a flow rate of 2 ml min−1 for 9 s, followed by a reduced flow rate at 0.01 ml min−1 to have the microarray incubated in the probe solution under the flow condition for 35 min (association phase of the reaction). The probe solution was then quickly replaced with 1× PBS at a flow rate of 2 ml min−1 for 9 s, followed by a reduced flow rate of 0.01 ml min−1 to allow dissociation of probe for 30 min (dissociation phase of the reaction). By repeating the binding reactions of STING at three different concentrations on separate fresh microarrays, binding curves of compounds with the target protein at three concentrations were recorded with a scanning OI‐RD microscope. Reaction kinetic rate constants were extracted by fitting the binding curves globally using 1‐to‐1 Langmuir reaction mode.

Generation of Flag‐STING and Flag‐cGAS stably transfected HEK293 cells

Flag‐STING stably transfected HEK293 cells were generated as previously described (Liu et al, 2019). HEK293 cells were transfected with Flag‐cGAS using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and cells were screened with hygromycin (MedChemExpress) to generate Flag‐cGAS stably transfected HEK293 cells.

Western blots

For immunoblotting, cell lysates or precipitates in 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) protein sample buffer were denatured at 95°C for 8 min and then were resolved by electrophoresis through a 4–15% SDS‐polyacrylamide gel. Separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and were incubated with the prespecified antibodies at the indicated dilutions. An enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was applied for immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation assays

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM of Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM of NaCl, 1% Triton X‐100, 1 mM of EDTA (pH 8.0)) supplemented with protease cocktail (P8340, Sigma‐Aldrich), 1 mM of PMSF, 1 mM of Na3VO4, and 1 mM of NaF. Cellular debris was cleared by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 min. For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were incubated with anti‐Flag M2 Affinity Gel (A2220, Sigma‐Aldrich) and monoclonal anti‐HA agarose (A2095, Sigma‐Aldrich) at 4°C overnight. Streptavidin Sepharose Bead Conjugate (#3419, Cell Signaling Technology) was used for immunoprecipitation of biotinylated c‐di‐AMP and biotinylated Palbociclib.

Stimulation of cells

Peritoneal macrophages were harvested and seeded on 12‐well plates or 6‐well plates. Cells were washed 3 h post seeding to remove dead cells and were further cultured overnight in replaced fresh culture medium. Cells were transfected with ISD (1 μg per million cells) by lipofectamine 2000; stimulated with cyclic dinucleotides including 2’3’‐cGAMP, 2’2’‐cGAMP, and c‐diAMP at the concentration of 0.1 μg/ml in the presence of digitonin (10 μg/ml); treated with LPS (0.1 μg/ml); or transfected with Poly(I:C) (1 μg/ml).

Molecular docking and dynamic simulation