Abstract

The emergence of zoonotic malaria in different parts of the world, including Indonesia poses a challenge to the current malaria control and elimination program that target global malaria elimination at 2030. The reported cases in human include Plasmodium knowlesi, P. cynomolgi and P. inui, in South and Southeast Asian region and P. brazilianum and P. simium in Latin America. All are naturally found in the Old and New-world monkeys, macaques spp. This review focuses on the currently available data that may represent primate malaria as an emerging challenge of zoonotic malaria in Indonesia, the distribution of non-human primates and the malaria parasites it carries, changes in land use and deforestation that impact the habitat and intensifies interaction between the non-human primate and the human which facilitate spill-over of the pathogens. Although available data in Indonesia is very limited, a growing body of evidence indicate that the challenge of zoonotic malaria is immense and alerts to the need to conduct mitigation efforts through multidisciplinary approach involving environmental management, non-human primates conservation, disease management and vector control.

Keywords: Primate malaria, Zoonotic malaria, Elimination strategy, One health

1. Introduction

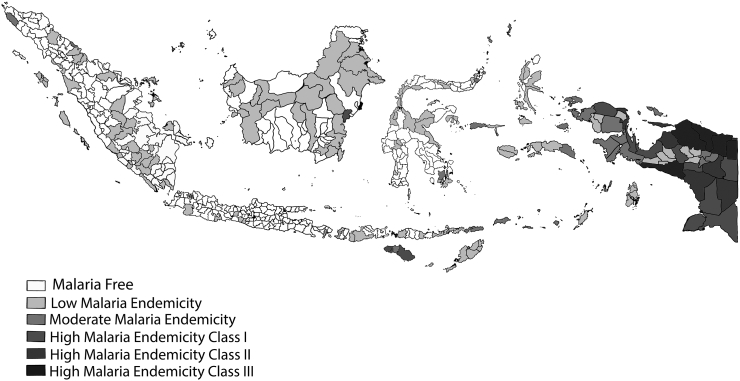

Malaria still poses a public health challenge in many countries around the world, including Indonesia. The objectives of malaria control programmes range from reducing the disease burden and maintaining it at a reasonably low level, to eliminate the disease from a defined geographical area, and ultimately eradicating the disease globally [1]. Currently, there are 241 million malaria cases in 2020 distributed in 85 malaria endemic countries (including the territory of French Guiana), increasing from 227 million in 2019, with the most of this increase coming from countries in the WHO Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asian regions [2]. In Indonesia, since the adoption of malaria elimination program in 2009, the incidence of malaria continuously decreases in the western parts of the country and as of 2020, over 300 Districts and municipalities have been declared to be malaria free (Fig. 1.). However, in Sumatra and Kalimantan (Indonesian part of Borneo), a new challenge has emerged with the rise of zoonotic malaria [3,4]. Human infection with various primate malaria such as Plasmodium knowlesi, P cynomolgi, and P inui have been tracked in various sites in Malaysia. It is highly possible that this phenomenon may also be happening in various locations in Indonesia where the non-human primate is endemic.

Fig. 1.

Malaria Free Areas in Indonesia. The figure was originally obtained from http://www.naturalearthdata.com, and modified according to data from Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia, 2022.

Malaria is a blood protozoan parasitic disease caused by genus Plasmodium spp., and transmitted to a wide variety of vertebrates by insect. It is believed that approximately 250 Plasmodium parasites parasitizes different animal species, including birds, reptiles, snakes, and mammals [[5], [6], [7]]. Of these, 27 Plasmodium species have been documented to infect a wide variety of non-human primates around the world, including apes, gibbons, and New and Old-World monkeys [8].

Humans have been infected with various Plasmodium species such as P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae. Some monkey malaria parasites have been experimentally transmitted to humans in the past through the bites of infected mosquitoes. They include P. cynomolgi [9,10], P. knowlesi [11,12], and P. inui [12] from Old World monkeys, P. brasilianum [13] and P. simium [13,14] from New World monkeys, and P. schwetzi (now regarded to be either P. vivax or P. ovale-like parasites) from chimpanzees [15].

The first zoonotic malaria report in 1964 was caused by P. knowlesi [16]. In 1971, another case report of P. knowlesi infected human from the same location in Peninsular Malaysia was published [17,18]. Until recently, many cases of natural human infection by P. knowlesi in Southeast Asia including Indonesia [[19], [20], [21]], Thailand [[22], [23], [24]], Malaysia [18,25], Philippines [26,27], Singapore [28], Brunei Darussalam [29], Laos [30], Myanmar [31], Cambodia [32], Vietnam [33], have been documented but so far no report from Timor Leste. Between 2004 and 2016, Malaysia Borneo reported 4553 cases and had the highest number of cases of P. knowlesi in humans, followed by Indonesia with 465 cases, and Peninsular Malaysia with 203 cases, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to confirm all of the cases [34]. The occurrence of zoonotic malaria has therefore hampered malaria control and elimination program that focuses to reduce the burden of human malaria in the region.

The non-human primate malaria parasites (NHPMPs) could potentially be a new challenge of malaria elimination in human in many parts of the world where the primate and human are sympatric [20]. Human natural infection with P. brazilianum and P. simium have been documented in Brazil, while P. knowlesi, P. cynomolgi and P. inui have been reported in Southeast Asia [9,10,[12], [13], [14],[16], [17], [18]]. Noteworthy, researchers from India also reported the occurrence of P. falciparum infection in Macaca mullata andM. radiata [35]. Different to other Plasmodium (Table 1), P. knowlesi has a 24-h erythrocytic cycle (quotidian) and can cause both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in humans [[36], [37], [38]]. Three predominant natural host of P. knowlesi is Macaca fascicularis, Macaca nemestrina, and M. leonina [[39], [40], [41], [42]]. Not only P. knowlesi, but also P. cynomolgi, P. inui, P. coatneyi, P. inui–like, and P. simiovale caused infection in human [[43], [44], [45]].

Table 1.

Plasmodium species that infect human and non-human primate worldwide [43].

| Vivax-type parasites | Ovale-type parasites | Malariae-type parasites | Falciparium-type parasites | Other-type parasites | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | P. vivax | P.ovale | P. malariae | P. falciparum | P. knowlesi |

| Macaque | P. cynomolgi |

P. fieldi P. simiovale |

P. inui |

P. coatneyi P. fragile |

|

| Gibbon |

P. eylesi P. hylobati Pithecophaga jefferyi P. youngi |

||||

| Orangutan | P. pitheci | ||||

| Chimpanzee | P. schwetzi | Prosevania rodhaini | |||

| Cacajao | P. brasilianum | ||||

| Howler monkey | P.simium | ||||

| Mangabey | P. gonderi | ||||

| Erythrocytic cycle parasite invasion | 48 h (Tertian) |

48 h (Tertian) |

72 (Quartan) |

48 h (Tertian) |

24 h (Quotidian) |

The archipelago of Indonesia stretches along the equatorial line, connecting the Asia mainland and Australia, and consists of 17,504 islands [46]. Indonesia uniquely has the second largest biodiversity in the world. There are 61 species of primates identified in Indonesia [47]. Sulawesi and Mentawai Islands particularly have endemic primate species [48,49]. Plasmodium pitheci was discovered to infect orangutans in 1907, as was Plasmodium inui, which parasitized Java monkeys [50].

This review will explore all malarial parasite species across humans and the non-human primate natural hosts, the habitat distribution of non-human primate, and the mosquito vector associated with the zoonotic malaria across a wide geographic and environmental region of Indonesia. Dramatic changes of land use, deforestation within the last 3 decades has intensified interaction between non-human primate with human being. It is, therefore, anticipated that the more interaction between human and non-human primate will facilitate the spill-over of many pathogens from human and non-human primate (Anthropo-zoonotic infection) or vice versa either through mosquito or direct transmission.

2. Non-human primate in Indonesia

Indonesia is home for a large number of primates species and occupies the third rank in the world after Brazil (116 species) and Madagascar (98 species) [47]. About 5 families from 11 genera and 61 species of primates have been documented, 38 species of which are endemic in Indonesia [[51], [52], [53]]. All primates distributed across archipelago based on genus from north Kalimantan to coast of Java and from the western part of Sumatra to east Timor (Table 2) [[54], [55], [56], [57], [58]]. Most primates in Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Java have similar genus with the types of primates in Asia, such as slow loris (Nycticebus), lutung (Trachypithecus), langur (Presbytis), monkey (Macaca), gibbon (Hylobates) [47,57]. But, orangutan (Pongo), proboscis (Nasalis), tarsies (Tarsius), and pig tailed langur (Simias) are not found in any others area in Asia [59].

Table 2.

Genus and species of non-human primate in Indonesia.

| Genusa,b | Speciesa,b | Islanda,b | Conservation Statusb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nycticebus | Nycticebus coucang Boddaert, 1785 | Sumatra | VU |

| Nycticebus javanicus E. Geoffroy, 1812 | Java | CR | |

| Nycticebus bancanus Lyon, 1906 | Sumatra and Kalimantan | NE | |

| Nycticebus borneanus Lyon, 1906 | Kalimantan | NE | |

| Nycticebus kayan Munds et al. 2013 | Kalimantan | NE | |

| Nycticebus managensis Trouessart, 1893 | Kalimantan | VU | |

| Tarsius | Tarsius tarsier Erxleben, 1777 | Sulawesi | VU |

| Tarsius fuscus Ischer, 1804 | Sulawesi | NE | |

| Tarsiun dentatus Miller & Hollister, 1921 | Sulawesi | VU | |

| Tarsius pelengensis Sody, 1949 | Sulawesi | EN | |

| Tarsius sangirensis Meyer, 1987 | Sulawesi | EN | |

| Tarsius tumpara Shekelle et al. 2008 | Sulawesi | CR | |

| Tarsius pumilus Miller & Hollister 1921 | Sulawesi | DD | |

| Tarsius lariang Merker & Groves, 2006 | Sulawesi | DD | |

| Tarsius wallacei Merker et al. 2010 | Sulawesi | DD | |

| Tarsius supriatnai Shekelle et al. 2017 | Sulawesi | – | |

| Tarsius spectrumgurskyae Shekelle et al. 2017 | Sulawesi | – | |

| Cephalopachus | Cephalopagus bancanus Horsfield, 1821 | Sumatra and Kalimantan | VU |

| Macaca | Macaca nemestrina Linnaeus, 1766 | Sumatra and Kalimantan | VU |

| Macaca siberu Fuentes & Olson, 1995 | Sumatra | VU | |

| Macaca pagensis Miller, 1993 | Sumatra | CR | |

| Macaca nigra Desmarest, 1822 | Sulawesi | CR | |

| Macaca nigrescens Temminck, 1849 | Sulawesi | VU | |

| Macaca tonkeana Meyer, 1899 | Sulawesi | VU | |

| Macaca ochreata Ogilby, 1841 | Sulawesi | VU | |

| Macaca hecki Matschie, 1901 | Sulawesi | VU | |

| Macaca maura Schinz, 1825 | Sulawesi | EN | |

| Macaca fascicularis Rafflles, 1821 | Sumatra | LC | |

| ^Macaca brunnescens | Sulawesi | – | |

| Hylobates | Hylobates lar Linnaeus, 1771 | Sumatra | EN |

| Hylobates agilis F. cuvier, 1821 | Sumatra | EN | |

| Hylobates albibarbis Lyon, 1911 | Kalimantan | EN | |

| Hylobates muelleri Martin, 1841 | Kalimantan | EN | |

| Hylobates abbotti Kloss, 1929 | Kalimantan | EN | |

| Hylobates funereus I.Geoffroy, 1850 | Kalimantan | EN | |

| Hylobates klossii Miller, 1903 | Sumatra | EN | |

| Hylobates moloch Audebert, 1798 | Java | EN | |

| Presbytis | Presbytis thomasi Collett, 1892 | Sumatra | VU |

| Presbytis melalophos Raffless, 1821 | Sumatra | EN | |

| Presbytis sumatrana Muller & Schlegel, 1841 | Sumatra | EN | |

| Presbytis bicolor, Aimi & Bakar 1992 | Sumatra | DD | |

| Presbytis mitrata Eschscholtz, 1821 | Sumatra | VU | |

| Presbytis comata Desmarest, 1822 | Java | EN | |

| Presbytis potenziani Bonaparte, 1886 | Sumatra | EN | |

| Presbytis siberu Chasen & Kloss, 1928 | Sumatra | EN | |

| Presbytis femoralis Martin, 1838 | Sumatra | NT | |

| Presbytis siamensis Muller & Schiegel, 1841 | Sumatra | NT | |

| Presbytis natunae Thomas & Hartert, 1894 | Kalimantan | VU | |

| Presbytis chrisomelas Muller, 1838 | Kalimantan | CR | |

| Presbytis rubiicunda Muller, 1838 | Kalimantan | LC | |

| Presbytis hosei Thomas, 1889 | Kalimantan | VU | |

| Presbytis cranicus Miller, 1834 | Kalimantan | EN | |

| Trachypithecus | Trachypithecus auratus E. Geoffroy, 1812 | Java | VU |

| Trachypithecus mauritius Griffith, 1821 | Java | VU | |

| Trachypithecus cristatus Raffless, 1821 | Sumatra and Kalimantan | NT | |

| Nasalis | Nasalis larvatus Wurmb, 1787 | Kalimantan | EN |

| Symphalangus | Simphalangus syndactilus Raffless, 1821 | Sumatra | EN |

| Simias | Simias concolor G.S. Miller 1930 | Sumatra | CR |

| Pongo | Pongo abelii Lesson, 1827 | Sumatra | CR |

| Pongo pygmeus Linnaeus, 1760 | Kalimantan | CR | |

| ⁎Pongo tapanuliensis Nurcahyo et al. 2017 | Sumatra | CR |

Primate species that are endemic in the Mentawai islands include the Mentawai pig tailed macaque M. pangenesis and the Mentawai langur (Presbytis potenziana) are only exclusively found in this island [47]. Previously, Sulawesi Island was known to be the home of seven macaque species [58,60,61], but recent finding revealed additional one new species [51] and at least nine species of tarsier [47]. Five species are protected and endangered; the black macaque (M. nigra), the moor macaque (M. maura), heck's macaque (Macaca hecki), the booted macaque (Macaca ochreata), and the tonkean macaque (Macaca tonkeana) [47,51]. The distribution of tarsiers; Dian's tarsier, Tarsius dentatus, and the Sulawesi mountain tarsier observed in Lore Lindu National Park, the province of Central Sulawesi. Orangutan is the only great ape in Indonesia, consisting of three species, such as Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii), Bornean orangutan (P. pygmaeus), and Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) [47].

3. Distribution of Plasmodium sp. among non-human primate in Indonesia

Until recently, very few studies have explored the malaria incidence among the non-human primate in Indonesia. Previously, studies conducted in various localities in Asia reported 7 species such as P. coatneyi, P. cynomolgi, P. fieldi, P. inui, P. knowlesi, P. fragile, and P. simiovale that infect non-human primate such as long tailed macaque (M. fascicularis) and leaf monkey. In particular, Plasmodium fragile was only reported in India and Sri Lanka, whereas P. simiovale was found only in Sri Lanka [52]. Macaques could be infected with a single, double, or even triple Plasmodium infections [53,59,62]. The presence of multiple Plasmodium infections in vertebrate hosts indicates a high malaria transmission intensity [63].

Plasmodium pitheci was discovered in Borneo's orangutan in 1907 [50]. At the same time, Plasmodium inui was discovered in Sumatra and Borneo (now called Kalimantan island) in Javanese monkeys or cynomolgus macaque (M. fascularis and M. nemestrina) [50]. Almost a century later, study to explore malaria parasite incidence among the non-human primate in Indonesia found P. cyonomolgi, P. inui, and P. fieldi infection in macaques from Southern Sumatra [64] using paired fecal and blood samples for molecular detection. Subsequently, a study involving 70 wild macaques from South Sumatra and Bintan island reported 92.8% parasite rate using nested PCR assays. They reported 48 macaques had single infection of P. cynomolgi, three macaques had single infection of P. inui, and one macaque infected with P. coatneyi and the remainders were either double or triple infected [62]. In 2017, another study screened Plasmodium DNA from 53 macaques, such as M. fascicularis, M. nemenstrina, and Presbytis sp. and found 38 positives, 57.9% of which were single infection, with either P. knowlesi, P. cynomolgi, P. inui and P. coatneyi, 28.9% were double infection, and 13.2% were triple infection, P. fieldi was not found in any macaque in this study [65]. In 2020, study from 2 captivities in Bogor, West Java using molecular detection reported 13.87% (38/274) of P. inui [66].

4. Zoonotic malaria among human in Indonesia

Zoonotic malaria cases had been reported in various localities in Sumatra and Kalimantan, Indonesia. Unlike in Malaysia, where zoonotic malaria is caused by P. knowlesi, P.cynomolgi, and P. inui [18,41,42,44,45,67,68], Plasmodium knowlesi, so far, was the only primate malaria species that has been reported from South Kalimantan (Borneo Island) [19], Aceh Besar [68], Batubara Langkat in Sumatra Island and South Nias [21].

In 2010, the first case was detected from an Australian that resided in South Kalimantan for 18 months and confirmed by molecular detection as 100% similar with P. knowlesi [19]. The second report was also in the same year, from 22 gold miners with uncomplicated malaria and were detected by nested PCR using P. knowlesi–specific primers that yielded a 153-bp product, in which 4 subjects were positive P. knowlesi [69]. The third case of P. knowlesi was detected by PCR from a worker at a charcoal mining company in Central Kalimantan [25]. The fourth case of P. knowlesi was formally reported from Aceh in 2016. The samples were diagnosed by microscopy, loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), and the PCR. The result showed that P. knowlesi was found in 20 samples out of 43 [70]. In 2018, P. knowlesi cases were discovered in Sabang Municipality Aceh, an area where P. falciparum and P. vivax had been eliminated [71].

5. Perspective of zoonotic malaria in the era of malaria elimination

Indonesia's Ministry of Health has implemented malaria control, with the goal of eliminating the disease by 2030. The increased incidence and proximity of natural reservoir hosts to humans and mosquitoes makes non-human primate malaria a necessary concern with knowlesi-malaria as one of the challenges for malaria elimination efforts in Indonesia.

The potential of exposure to P. knowlesi outdoor transmission has increased as humans have encroached on previously forested areas. Outdoor workers (e.g., plantation and agricultural workers) are particularly vulnerable [19,[27], [69],[72], [73], [75]]. The transmission dynamics of P. knowlesi appear to be primarily macaque-vector-human. However, adaptation to human-vector-human transmission is possible whenever a large number of human infected cases and mosquito vector are present [76]. Therefore, one health approach to mitigate zoonotic malaria transmission is mandatory. The concept of One Health (OH) refer to collaborative approach to health challenges that acknowledges the intersection of human medicine, veterinary medicine and environmental science [77].

5.1. Improved zoonotic malaria surveillance in human

To develop a comprehensive plan to control zoonotic malaria, it is necessary to first accurately determine the disease's prevalence in non-human primate. Further research on the malaria prevalence among various non human primate, bionomics and blood meal preference of the incriminated mosquito vectors and the intensity of human-primate interaction are needed to assess the distribution and relative risk of zoonotic-malaria infection in human populations, in order to design an appropriate control interventions. Furthermore, tracking the genetic subpopulations of primate malaria species should help researchers better understand the transmission dynamics in areas where the human-non human primate interaction and determine whether there is a link between unique knowlesi-malaria genetic subpopulations and clinical outcomes [72,75].

5.2. Non-human primate conservation strategies related to forest restoration and deforestation regulations

Conservation efforts have been made and are still being made in Indonesia (sustainable). Since 1940 Indonesia has Java-Madura Hunting Regulation, then in 1954 worked with International Unit Conservation Nature (IUCN) for wildlife sanctuary rehabilitation, and based on the Decree of the Minister of Agriculture No. 428 / Kpts / Org / 7/1978 dated June 10, 1978, eight Natural Resources Conservation Centers (BKSDA) were established as Technical Implementation Units (UPT) in the field of protection and preservation of nature and responsible to the Director General of Forestry. Even Indonesia has a forest police to protect forest areas, flora and fauna in conservation areas until now. But the new challenges to Indonesia's biodiversity are threatened by habitat degradation, invasive foreign species, and genetic resources theft [78].

The nature of biodiversity and zoonotic pathogen spill over risk to human is depending on the disease system, local ecology, and human social behavior. Thus, local governments should take any necessary steps to counter the concerns posed by agricultural enterprises by regulating forest conversion into either plantation or mining location, and supporting alternate uses of wooded land that are beneficial to biodiversity

5.3. Vector control strategies for the mitigation of zoonotic malaria transmission

Mosquitoes are the most common arthropod vectors of human disease, carrying malaria, lymphatic filariasis, and arboviruses like dengue and Zika virus globally. Unfortunately, most of these vector-borne diseases control still rely solely on vector control as chemotherapeutic treatment and prevention are currently nor available. Therefore, evidence-based vector control is the only option to mitigate the diseases transmission, particularly that occur in outdoor setting and in this regard necessitate a sustainable vector surveillance and control measures [79]. Traditional mosquito control methods have heavily relied on many chemicals to kill mosquitoes. Currently, many innovative vectors control intervention have been developed to control specific vector borne diseases like malaria. For outdoor/forest malaria transmission the use of personal repellent when travelling through the forest and spatial repellent could be considered in addition to the use of insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs).

In the context of zoonotic malaria which transmission mainly occur outdoor/ or in the forest, the main mosquito vector involved in the transmission are so far members of Anopheles leucosphyrus group such as An leucosphyrus subgroup and A. hackeri that are distributed in Indonesia from Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and lesser Sunda islands [80,81], and co-exist with various species of non-human primates. To mitigate the transmission, therefore, emphasis should be put on human to prevent the contact with mosquito vector.

6. Conclusion

The emergence of zoonotic malaria in Indonesia, particularly in areas where non-human primates and human are living in close proximity alerts to the need of appropriate mitigation efforts to reduce the risk to people as well as to protect the non-human primates who face extinction in some species. The natural habitat of the non-human primates should be carefully considered before converting the forest into the agricultural use and human re-settlement.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Directorate General of Higher Education Ministry of Education and Culture Republic of Indonesia for providing the Pendidikan Magister menuju Doktor untuk Sarjana Unggul (PMDSU) Program and also express special thanks to all staff at the laboratory of the malaria and vector resistance unit, the Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jakarta, Indonesia, for their support.

References

- 1.World Malaria Report. World Health Organization Press 2008; Geneva: 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43939 [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Malaria Report. World Health Organization Press 2021; Geneva: 2021. https://who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040496 [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Malaria Report. World Health Organization Press 2019; Geneva: 2019. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241565721 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Malaria Report. World Health Organization 2020; Geneva: 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015791 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garnham P.C.C. Malaria parasites and other Haemosporidia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene. 1967;16:561–563. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1967.16.561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Telford S.R. CRC Press; 2009. Hemoparasites of the Reptilia. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valkiūnas G. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2005. Avian Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinelli A., Culleton R. Non-human primate malaria parasites: out of the forest and into the laboratory. Parasitology. 2018;145:41–54. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eyles D.E., Coatney R., Getz M.E. Vivax-type malaria parasite of macaques transmissible to man. Science. 1960;131:1812–1813. doi: 10.1126/science.131.3416.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coatney G.R., Elder H.A., Contacos P.G., Getz M.E., Greenland R., Rossan R.N., Schmidt L.H. Transmission of the M strain of Plasmodium cynomolgi to man. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1961:673–678. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1961.10.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin W., Contacos P.G., Collins W.E., Jeter M.H., Alpert E. Experimental mosquito-transmission of Plasmodium knowlesi to man and monkey. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1968;17:355–358. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1968.17.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coatney G.R., Chin W., Contacos P.G., King H.K. Plasmodium inui, aquartan-type malaria parasite of old world monkeys transmissible to man. J. Parasitol. 1966;52:660–663. doi: 10.2307/3276423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contacos P.G., Lunn J.S., Coatney G.R., Kilpatrick J.W., Jones F.E. Quartan-type malaria parasite of new world monkeys transmissible to man. Science. 1963:676. doi: 10.1126/science.142.3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deane L.M., Deane M.P., Ferreira N.J. Studies on transmission of simian malaria and on a natural infection of man with Plasmodium simium in Brazil. Bull. World Health Organ. 1966;35:805–808. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/263151 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contacos P.G., Coatney G.R., Orihel T.C., Collins W.E., Chin W., Jeter M.H. Transmission of Plasmodium schwetzi from the chimpanzee to man by mosquito bite. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1970;19:190–195. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin W., Contacos P.G., Coatney G.R., Kimball H.R. A naturally acquired quotidian-type malaria in man transferable to monkey. Science. 1965;149 doi: 10.1126/science.149.3686.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fong Y.L., Cadigan F.C., Coatney G.R. A presumptive case of naturally occurring Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in man in Malaysia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1971;65:839–840. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(71)90103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh B., Sung L.K., Matusop A., Radhakrishnan A., Shamsul S.S.G., Cox-Singh J., Thomas A., Conway D.J. A large focus of naturally acquired Plasmodium knowlesi infections in human beings. Lancet. 2004;363:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15836-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figtree M., Lee R., Bain L., Kennedy T., Mackertich S., Urban M., Cheng Q., Hudson B.J. Plasmodium knowlesi in human, Indonesian Borneo. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:672–674. doi: 10.3201/eid1604.091624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Setiadi W., Sudoyo H., Trimarsanto H., Sihite B.A., Saragih R.J., Juliawaty R., Wangsamuda S., Asih P.B.S., Syafruddin D. A zoonotic human infection with simian malaria, Plasmodium knowlesi, in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Malar. J. 2016;15:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1272-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lubis I.N.D., Wijaya H., Lubis M., Lubis C.P., Divis P.C.S., Beshir K.B., Sutherland C.J. Contribution of Plasmodium knowlesi to multispecies human malaria infections in North Sumatra, Indonesia. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;215:1148–1155. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jongwutiwes S., Putaporntip C., Iwasaki T., Sata T., T. Study Naturally acquired knowlesi malaria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:2211–2213. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Putaporntip C., Hongsrimuang T., Seethamchai S., Kobasa T., Limkittikul K., Cui L., Jongwutiwes S. Differential prevalence of Plasmodium infections and cryptic Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in humans in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;199:1143–1150. doi: 10.1086/597414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jongwutiwes S., Buppan P., Kosuvin R., Seethamchai S. Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in humans and macaques, Thailand. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;10:1799–1806. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper D.J., Rajahram G.S., William T., Jelip J., Mohammad R., Benedict J., Alaza D.A., Malacova E., Yeo T.W., Grigg M.J., Anstey N.M., Barber B.E. Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in Sabah, Malaysia, 2015–2017: ongoing increase in incidence despite near-elimination of the human-only Plasmodium species. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;70:361–367. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luchavez J., Espino F., Curameng P., Espina R., Bell D., Chiodini P.L., Nolder D., Sutherland C., Lee K.S., Singh B. Human infections with Plasmodium knowlesi, the Philippines. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14:811–8113. doi: 10.3201/eid1405.071407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fornace K.M., Herman L.S., Abidin T.R., Chua T.H., Daim S., Lorenzo P.J., Grignard L., Nuin N.A., Ying L.T., Grigg M.J., William T., Espino F., Cox J., Teteh K.K.A., Drakeley C.J. Exposure and infection to Plasmodium knowlesi in case study communities in Northern Sabah, Malaysia and Palawan, The Philippines. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng O.T., Ooi E.E., Lee C.C., Lee P.J., Ng L.C., Pei S.W., Tu T.M., Loh J.P., Leo Y.S. Naturally acquired human Plasmodium knowlesi infection, Singapore. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14:814–816. doi: 10.3201/eid1405.070863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koh G.J.N., Ismail P.K., Koh D. Occupationally acquired Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in Brunei Darussalam. Saf. Health Work. 2019;10:122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwagami M., Nakatsu M., Khattignavong P., Soundala P., Lorphachan L., Keomalaphet S., et al. First case of human infection with Plasmodium knowlesi in Laos. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang N., Chang Q., Sun X., Lu H., Yin J., Zhang Z., Wahlgren M., Chen Q. Co-infections with Plasmodium knowlesi and other malaria parasites, Myanmar. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;9:1476–1478. doi: 10.3201/eid1609.100339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khim N., Siv S., Kim S., Mueller T., Fleischmann E., Singh B., Divis P.C.S., Steenkeste N., Duval L., Bouchier C., Duong S., Ariey F., Ménard D. Plasmodium knowlesi infection in humans, Cambodia, 2007-2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:1900–1902. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maeno Y., Culleton R., Quang N.T., Kawai S., Marchand R.P., Nakazawa S. Plasmodium knowlesi and human malaria parasites in Khan Phu, Vietnam: gametocyte production in humans and frequent co-infection of mosquitoes. Parasitology. 2017;144:527–535. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016002110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization . Malaria Policy Advisory Committee, Geneva; Switzerland: 2017. Outcomes from the evidence review group on Plasmodium knowlesi.https://www.who.int/malaria/mpac/mpac-mar2017-plasmodium-knowlesi-presentation.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dixit J., Zachariah A., S.P.K, Chandramohan B., Shanmuganatham V., Karanth K.P. Reinvestigating the status of malaria parasite (Plasmodium sp.) in Indian non-human primates. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed Md.A., Fong M.Y., Lau Y.L., Yusof R. Clustering and genetic differentiation of the normocyte binding protein (nbpxa) of Plasmodium knowlesi clinical isolates from Peninsular Malaysia and Malaysia Borneo. Malar. J. 2016;15:241. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daneshvar C., William T., Davis T.M.E. Clinical features and management of Plasmodium knowlesi infections in humans. Parasitology. 2018;145:18–31. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016002638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imwong M., Madmanee W., Suwannasin K., Kunasol C., Peto T.J., Tripura R., von Seidlein L., Nguon C., Davoeung C., Day N.P.J., Dondrop A.M., White N.J. Asymptomatic natural human infections with the simian malaria parasites Plasmodium cynomolgi and Plasmodium knowlesi. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;219:695–702. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee K.S., Divis P.C.S., Zakaria S.K., Matusop A., Julin R.A., Conway D.J., Cox-Singh J., Singh B. Plasmodium knowlesi: reservoir hosts and tracking the emergence in humans and macaques. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Divis P.C.S., Singh B., Anderios F., Hisam S., Matusop A., Kocken C.H., Assefa S.A., Duffy C.W., Conway D.J. Admixture in humans of two divergent Plasmodium knowlesi populations associated with different macaque host species. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assefa S., Lim C., Preston M.D., Duffy C.W., Nair M.B., Adroub S.A., Kadir K.A., Goldberg J.M., Neafsey D.E., Divis P., Clark T.G., Duraisingh M.T., Conway D.J., Pain A., Singh B. Population genomic structure and adaptation in the zoonotic malaria parasite Plasmodium knowlesi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509534112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moyes C.L., Shearer F.M., Huang Z., Wiebe A., Gibson H.S., Nijman V., Mohd-Azlan J., Brodie J.F., Malaivijitnond S., Linkie M., Samejima H., O’Brien T.G., Trainor C.R., Hamada Y., Giordano A.J., Kinnaird M.F., Elyazar I.R.F., Sinka M.E., Vythilingam I., Bangs M.J., Pigott D.M., Weiss D.J., Golding N., Hay S.I. Predicting the geographical distributions of the macaque hosts and mosquito vectors of Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in forested and non-forested areas. Parasit. Vectors. 2016;9:242. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1527-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coatney G.R., Collins W.E., Warren M., Contacos P.G. US Goverment Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1971. The Primate Malarias. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ta T.H., Hisam S., Lanza M., Jiram A.I., Ismail N., Rubio J.M. First case of a naturally acquired human infection with Plasmodium cynomolgi. Malar. J. 2014;13:68. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yap N.J., Hossain H., Nada-Raja T., Ngui R., Muslim A., Boon-Peng H., Khaw L.T., Kadir K.A., Divis P.C.S., Vythilingam I., Singh B., Y. Ai-Lian Lim, natural human infections with Plasmodium cynomolgi, P. inui, and 4 other simian malaria parasites. Malaysia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27:2187–2191. doi: 10.3201/eid2708.204502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poermono A., Kuswarini A. Cambridge University Press; 2019. Climate Change and Ocean Governance Politics and Policy for Threatened Seas. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Supriatna J. 2019. Field Guide to the Indonesia Primates Pustaka Obor Indonesia, Jakarta. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brandon-Jones D., Eudey A.A., Geissmann T., Groves C.P., Melnick D.J., Morales J.C., Shekelle M., Stewart C.B. Asian primate classification. Int. J. Primatol. 2004;25:97–164. doi: 10.1023/B:IJOP.0000014647.18720.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shekelle M., Groves C.P., Mittermeier A., Salim A., Spinger M.S. A new tarsier species from the Togean Islands of Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, with references to Wallacea and conservation on Sulawesi. Primate Conserv. 2019;33:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halberstadter L., Prowazek S.V. Untersuchungen ueber die Malaria parasiten der Affen. Arb. K. Gesundh. -Amte (Berl.) 1907;26:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mustari A.H. IPB Press; Bogor, Indonesia: 2020. Manual identifikasi dan bio-Ekologi spesies kunci di Sulawesi. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fooden J. Malaria in macaques. Int. J. Primatol. 1994;15:573–596. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Irene L. National University of Singapore; 2011. Identification and Molecular Characterisation of Simian Malaria Parasites in Wild Monkeys of Singapore; p. 184. MSc thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gursky S., Supriatna J. Springer; New York: 2010. Indonesian Primates. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Groves C. The what, why, and how of primate taxonomy. Int. J. Primatol. 2004;25:1105–1126. doi: 10.1023/B:IJOP.0000043354.36778.55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mittermeier R.A., Rylands A.B., Wilson D.E. Lynx Edicions; 2013. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roos C., Boonratana R., Supriatna J., Followes J., Groves C.P., Nash S.D., Rylands A.B., Mittermeier R.A. An updated taxonomy and conservation status review of Asian primates. Asian Primates J. 2014;4 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Supriatna J. Paparan Penerima Habibie Award; Jakarta: 2008. Biogeografi Indonesia dan keberagaman primata: Pendekatan biogeografi pulau dalam pelestarian primata di Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X., Kadir K.A., Quintanilla-Zarinan L.F., Villano J., Houghton P., Du H., Singh B., Smith D.G. Distribution and prevalence of malaria parasites among long- tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in regional populations across Southeast Asia. Malar. J. 2016;15:450. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1494-0. doi:10.1186/s12936-016-1494-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Supriatna J. In: Fakultas Kedokteran Hewan dan Kehutanan Univ. Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta. Yuda P., Salasia S.I.O., editors. 2000. Status konservasi satwa primata dalam konservasi satwa primata: Tinjauan ekologi, sosial ekonomi, dan medis dalam perkembangan ilmu pengetahuan dan teknologi; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riley E.P. The endemic seven: four decades of research on the Sulawesi macaques. Evol. Anthropol. 2010;19:22–36. doi: 10.1002/evan.20246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raja T.N., Hu T.H., Kadir K.A., Mohamad D.S.A., Rosli N., Wong L.L., Hii K.C., Divis P.C.S., Singh B. Naturally acquired human Plasmodium cynomolgi and P. knowlesi infections, Malaysian Borneo. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;8:1801–1809. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.200343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arez A.P., Pinto J., Pålsson K., Snounou G., Jaenson T.G.T., do Rosário V.E. Transmission of mixed Plasmodium species and Plasmodium falciparum genotypes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003;68:161–168. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.2.0680161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siregar J.E., Faust C.L., Murdiyarso L.S., Rosmanah L., Saepuloh U., Dobson A.P., Iskandriati D. Non-invasive surveillance for Plasmodium in reservoir macaque species. Malar. J. 2015;14:404. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0857-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salwati E., Handayani S., Dewi R.M. Mujiyanto, Kasus baru Plasmodium knowlesi pada manusia di Jambi, Jurnal Biotek Medisiana. Indonesia. 2017;6:39–51. http://ejournal2.litbang.kemkes.go.id/index.php/jbmi/article/view/1684/887 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kesumawati U., Rosmanah L., Soviana S., Darusman H.S. Morphological features and molecular of Plasmodium inui in Macaca fascicularis from Bogor, West Java. Adv. Biol. Sci. Res. 2020;12 doi: 10.2991/absr.k.210420.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grignard L., Shah S., Chua T.H., William T., Drakeley C.J., Fornace K.M. Natural human infections with Plasmodium cynomolgi and other malaria species in an elimination setting in Sabah, Malaysia. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;220:1946–1949. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liem J.W.K., Bukhari F.D.M., Jeyeprakasam N.K., Phang W.K., Vythilingam I., Lau Y.L. Natural Plasmodium inui infections in humans and Anopheles cracens mosquito, Malaysia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27:2700–2703. doi: 10.3201/eid2710.210412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sulistyaningsih E., Fitri L.E., Löscher T., Berens-Riha N. Diagnostic difficulties with Plasmodium knowlesi infection in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:1033–1034. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.100022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Herdiana H., Cotter C., Coutrier F.N., Zarlinda I., Zelman B.W., Tirta Y.K., Greenhouse B., Gosling R.D., Baker P., Whittaker M., Hsiang M.S. Malaria risk factor assessment using active and passive surveillance data from Aceh Besar, Indonesia, a low endemic, malaria elimination setting with Plasmodium knowlesi, Plasmodium vivax, and Plasmodium falciparum. Malar. J. 2016;15:468. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1523-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Herdiana H., Irnawati I., Coutrier F.N., Munthe A., Mardiati M., Yuniarti T., Sariwati E., Sumiwi M.E., Noviyanti R., Pronyk P., Hawley W.A. Two clusters of Plasmodium knowlesi cases in a malaria elimination area, Sabang municipality, Aceh, Indonesia. Malar. J. 2018;17:186. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2334-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ekawati L.L., Johnson K.C., Jacobson J.O., Cu eto C.A., Zarlinda I., Elyazar I.R.F., Fatah A., Sumiwi M.E., Noviyanti R., Cotter C., Smith J.L., Coutrier F.N., Bennett A. Defining malaria risks among forest workers in Aceh, Indonesia: a formative assessment. Malar. J. 2020;19:441. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03511-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grigg M.J., Cox J., William T., Jelip J., Fornace K.M., Brock P.M., von Seidlein L., Barber B.E., Anstey N.M., Yeo T.W., Drakeley C.J. Individual-level factors associated with the risk of acquiring human Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in Malaysia: a case-control study. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1 doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30031-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Divis P.C.S., Hu T.H., Kadir K.A., Mohammad D.S.A., Hii K.C., Daneshvar C., Conway D.J., Singh B. Efficient surveillance of Plasmodium knowlesi genetic subpopulations, Malaysian Borneo, 2000–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1392–1398. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.190924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Subbarao S.K. Plasmodium knowlesi: from macaque monkeys to humans in south-east and the risk of its spread in India. J. Parasit. Dis. 2011;35:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s12639-011-0085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ruis-Castillo P., Rist C., Rabinovich R., Chaccour C. Insecticide-treated livestock: a potential one health approach to malaria control in Africa. Trends Parasitol. 2022:38. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.IUCN, The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. http://www.iucnredlist.org (Accessed 23 November 2021).

- 79.Beier J.C., Wilke A.B.B., Benelli G. Newer approaches for malaria vector control and challenges of outdoor transmission. IntechOpen. 2018 doi: 10.5772/intechopen.75513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sallum Maria Anice Mureb, Peyton E.L., Harrison Bruce Arthur, Wilkerson Richard Charles. Revision of the Leucosphyrus group of Anopheles (Cellia) (Diptera, Culicidae) Rev. Brasil. Entomol. 2005;49(Supl. 1):1–152. doi: 10.1590/S0085-56262005000500001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jessica S. Proposed integrated control of zoonotic plasmodium knowlesi in Southeast Asia using themes of one health. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5(4)):175. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5040175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]