This cohort study compares outcomes of 104 patients with unresectable locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer with and without driver variations treated with the PACIFIC regimen.

Key Points

Question

Do driver variations in unresectable locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) alter clinical outcomes of treatment with definitive chemoradiation and consolidative durvalumab?

Findings

In this cohort study of 104 patients with locally advanced non–small cell lung treated with definitive chemoradiation and consolidative durvalumab, KRAS and non–KRAS driver variations were associated with significantly shorter progression-free survival (8.4 months vs 40.1 months).

Meaning

These findings suggest that chemoradiation and consolidative durvalumab is less beneficial for locally advanced NSCLC with driver variations; alternative therapies for these patients require consideration.

Abstract

Importance

Consolidative durvalumab after definitive chemoradiation for unresectable locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) can significantly improve progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), as shown in the PACIFIC trial. However, whether patients with driver variations derive equal benefit from this regimen remains unclear.

Objectives

To compare outcomes of patients with locally advanced NSCLC with and without driver variations treated with the PACIFIC regimen.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study examined 104 patients with unresectable locally advanced NSCLC with mutational profiling treated at a tertiary cancer center with definitive chemoradiation and consolidative durvalumab from June 2017 through May 2020. Patients with recurrent disease or those receiving postoperative therapy were excluded. Outcomes were analyzed with Kaplan-Meier and multivariate regression analyses.

Exposures

Patients were grouped according to the presence of non–KRAS driver variations (EGFR exon 19 deletion, EGFR exon 20 insertion, EGFR exon 21 mutation [L858R], ERBB2 exon 20 insertion, EML4-ALK fusion, MET exon 14 skipping, NTRK2 fusion), KRAS driver variations, or no driver variations.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were PFS, OS, and second progression-free survival (PFS2) times.

Results

The 104 patients had a median (IQR) age of 65.1 (9.8) years, with 55 females (53%) and 85 former or current smokers (88%). There were 43 patients (41%) with driver variations with a median PFS time of 8.4 months vs 40.1 months for patients without driver variations (hazard ratio [HR], 2.75; 95% CI, 1.64-4.62; log-rank P < .001). Both patients with non–KRAS and KRAS driver variations had worse PFS. No difference in OS was found between patients with and without driver variations (log rank P = .24). Among the 63 patients who developed progressive disease, those with non–KRAS driver variations had a median PFS2 time of 13.7 months vs 4.4 months for all other patients (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.64; log-rank P = .001). Rates of overall grade 2 toxic effects or higher did not differ by driver mutation status.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, driver variations in patients with unresectable locally advanced NSCLC were associated with significantly shorter PFS time after definitive chemoradiation and consolidative durvalumab. These findings suggest the need to consider additional or alternative treatment options to the PACIFIC regimen for patients with driver variations.

Introduction

The treatment of unresectable locally advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a disease with high recurrence rates and mortality, has been revolutionized by the phase 3 PACIFIC trial, which revealed that up to 1 year of consolidative therapy with durvalumab, an antiprogrammed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) agent, after chemoradiation (CRT) led to significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).1,2 However, the benefit of this regimen for patients with variations in driver oncogenes such as EGFR or KRAS is uncertain.2,3 Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been developed against many non–KRAS variations and recently for KRAS G12C variations, resulting in promising outcomes.4,5,6,7

In this retrospective cohort analysis, we explored clinical outcomes of patients with unresectable locally advanced NSCLC who received CRT followed by consolidative durvalumab and stratified outcomes by the presence of non–KRAS driver variations, KRAS driver variations, or no driver variations. Additionally, we explored patterns of failure and salvage outcomes for patients who progressed and assessed treatment-related toxicities.

Methods

Study Design

The institutional review board at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center granted approval for this retrospective review, and all patients provided informed consent. Informed consent for treatments in the study are documented in the electronic medical record. Patients with unresectable locally advanced NSCLC who received concurrent CRT and at least 1 cycle of adjuvant durvalumab between June 2017 and May 2020 were identified by querying a single-institution database of patients with NSCLC with variation profiling. Of an initial 267 patients who fit these criteria, we excluded patients who were not treated definitively, did not receive durvalumab with consolidative intent, had stage IV disease, had recurrent disease, or received upfront surgery to yield a final total of 104 patients. Patients were grouped according to the presence or absence of driver variations (EGFR exon 19 deletion, EGFR exon 20 insertion, ERBB2 exon 20 insertion, EGFR exon 21 variation [L858R], ALK-EML4 fusion, MET exon 14 skipping, NTRK2 fusion, or KRAS variation). The driver variation group was further subgrouped by KRAS or non–KRAS variations. Variation profiling was performed with next-generation sequencing panels of 50, 70, or 134 genes in our institutional molecular diagnostics laboratory.

Baseline demographic information (ie, age, sex, race, and smoking status), performance status, histology, staging, treatment details (ie, chemotherapy and radiation regimen), PD-L1 status, and clinical outcomes (ie, PFS, second progression-free survival [PFS2], and OS) were obtained from electronic medical records. Race was recorded based on the category of Asian, Black, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, or White as recorded in the electronic medical record. Race was considered on the basis that driver variations may have different prevalence based on race. Histologic classification of NSCLC was defined based on World Health Organization criteria.8 Disease staging was based on the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual.9

Study Outcomes

PFS was measured from the date of CRT completion to the date of disease recurrence, death from any cause, or last follow-up. We defined recurrence based on pathologic or radiographic standards as defined in the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1.10 OS was measured from the date of CRT completion to the date of death from any cause or last follow-up. For those with progressive disease, the PFS2 time was measured from the date of the first progression to the date of subsequent progression, death from any cause, or last follow-up. Patient follow-up in the medical record was recorded until December 1, 2021. Adverse effects were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Effects (CTCAE) version 5.0.

Statistical Analysis

PFS, PFS2, and OS across variation groups were evaluated with Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and hazard ratios (HRs) were generated using log-rank tests. Censoring was used for patients with incomplete follow-up data. Comparisons for PFS and OS were performed with 2 groups (ie, driver variations and no driver variations) and with 3 groups (ie, non–KRAS driver variations, KRAS driver variations, and no driver variations). Comparisons for PFS2 were performed with 2 groups (ie, non–KRAS drivers vs all other variations) and with 3 groups (ie, non–KRAS driver, KRAS drivers, and nondrivers). A subgroup analysis of PFS, OS, and PFS2 with patients without squamous cell histology was performed with Kaplan-Meier survival curves with HRs generated using log-rank tests.

Comparisons by patient characteristics were made with analysis of variance for continuous variables and with the Freeman-Fisher-Halton exact test for categorical variables. Control for confounding in PFS and PFS2 was performed using multivariate regression analysis with variation status, sex, smoking status, stage, age, performance status, PD-L1 status, and histology as independent variables. HRs for each variable were estimated from Cox proportional hazards regression models. Toxic effects rates, patterns of progression, and rates of oligoprogression (defined as 3 or fewer discrete lesions) were compared with the Freeman-Fisher-Halton exact test. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P value of .05 or less. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated in Prism version 9 (GraphPad). Stata version 15 (StataCorp) was used for all statistical tests.

Results

For the 104 patients in our cohort (Table 1), 43 (41%) had driver variations and these patients were more likely than patients with nondriver variations to have adenocarcinoma histology (37 [86%] vs 29 [48%]; P < .001), be female (31 [72%] vs 24 [39%]; P = .004), be an Asian, Black, Hispanic, or Middle Eastern individual (10 [23%] vs 6 [10%]; P = .013) and be never smokers (10 [23%] vs 2 [3%]; P < .001). Among patients with non–KRAS driver variations, EGFR variations were the most common (12 [57%]). Specific variations for all patients are listed in the eTable 1 in the Supplement. Of patients with driver variations, 33 (77%) had variation profiling performed prior to starting chemoradiation. The median (IQR) follow-up for the cohort was 23.6 (14.3-33.4) months.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics Stratified by Variation Status.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 104) | Non–KRAS driver variations (n = 21) | KRAS driver variations (n = 22) | Nondriver variations (n = 61) | ||

| Age at completion of CRT, mean (SD), y | 65.1 (9.8) | 63.8 (11.0) | 66.8 (9.1) | 65.0 (9.7) | .59 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 49 (47) | 6 (29) | 6 (27) | 37 (61) | .004 |

| Female | 55 (53) | 15 (71) | 16 (73) | 24 (39) | |

| Race | .013 | ||||

| Asian | 4 (4) | 4 (19) | 0 | 0 | |

| Black | 8 (8) | 1 (5) | 3 (14) | 4 (7) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (2) | 1 (5) | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Middle Eastern | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| White | 88 (85) | 15 (71) | 18 (82) | 55 (90) | |

| Smoking status | <.001 | ||||

| Current | 14 (13) | 0 | 3 (14) | 11 (18) | |

| Former | 78 (75) | 11 (52) | 19 (86) | 48 (79) | |

| Never | 12 (12) | 10 (48) | 0 | 2 (3) | |

| Histology | <.001 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 66 (64) | 17 (81) | 20 (91) | 29 (48) | |

| Squamous | 33 (32) | 3 (14) | 0 | 30 (49) | |

| Adenosquamous | 3 (3) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| Giant cell | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | |

| Sarcomatoid | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Disease stage at CRT | .62 | ||||

| IIB | 6 (6) | 0 | 1 (4) | 5 (8) | |

| IIIA | 37 (36) | 8 (38) | 8 (36) | 19 (31) | |

| IIIB | 53 (51) | 9 (43) | 12 (55) | 32 (53) | |

| IIIC | 10 (10) | 4 (19) | 1 (5) | 5 (8) | |

| ECOG PS score at CRT | .38 | ||||

| 0-1 | 95 (91) | 21 (100) | 20 (91) | 54 (89) | |

| 2 | 9 (9) | 0 | 2 (9) | 7 (11) | |

| CRT regimen | .11 | ||||

| Cisplatin/etoposide | 2 (2) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 0 | |

| Cisplatin/pemetrexed | 6 (6) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | 3 (5) | |

| Cisplatin/docetaxel | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Carboplatin/docetaxel | 1 (1) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | |

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 88 (85) | 14 (67) | 20 (91) | 54 (89) | |

| Carboplatin/pemetrexed | 4 (4) | 3 (14) | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Carboplatin/etoposide | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Carboplatin only | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Radiation dose, Gy | .85 | ||||

| 60 | 12 (12) | 3 (14) | 2 (9) | 7 (12) | |

| 66 | 76 (73) | 15 (71) | 16 (73) | 45 (74) | |

| 68 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | |

| 69.6 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| 70 | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (3) | |

| 72 | 7 (7) | 2 (10) | 1 (4) | 4 (7) | |

| 77 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| Unknown | 4 (4) | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 2 (3) | |

| PD-L1 expression | .32 | ||||

| Negative (0% TPS) | 11 (11) | 4 (19) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (5) | |

| Low (1%-49% TPS) | 36 (35) | 6 (29) | 6 (27.3) | 24 (39) | |

| High (≥50% TPS) | 23 (22) | 3 (14) | 6 (27.3) | 14 (23) | |

| Not tested | 34 (33) | 8 (38) | 6 (27.3) | 20 (33) | |

| Follow-up, median, mo | 23.6 | 32.6 | 21.9 | 23.8 | .26 |

Abbreviations: CRT, chemoradiation therapy; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; PD-LI, antiprogrammed cell death ligand 1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

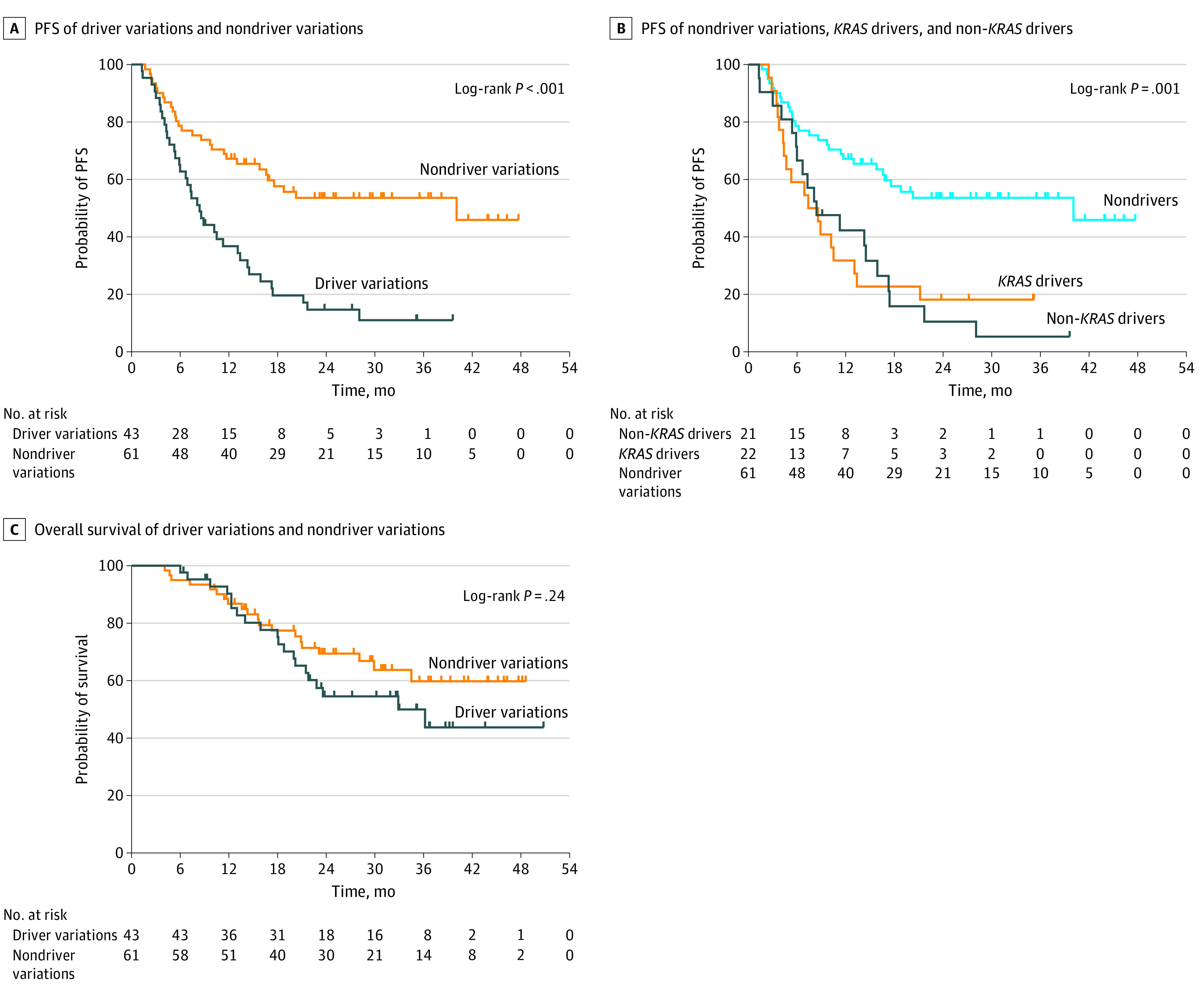

PFS and OS After CRT With Consolidative Durvalumab

The median (IQR) PFS time for all patients was 14.5 months (5.7 months to not achieved). Patients with driver variations, both non–KRAS (8.4 months) and KRAS (8.0 months), had significantly shorter median PFS times (8.4 months vs 40.1 months; HR, 2.75; 95% CI, 1.64-4.62; P < .001) (Figure 1). On multivariate analysis, non–KRAS driver variation, KRAS driver variation, stage IIIC disease, and ECOG 2 were associated with worse PFS (Table 2). No significant difference was found in OS time between patients with driver variations (median [IQR], 36.2 months [IQR, 18.1 months to not achieved]) and those without (median not achieved) (P = .24) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival for Patients With NSCLC With or Without Driver Variations Treated With Definitive Chemoradiation and Consolidative Durvalumab.

A, Median PFS time was 8.4 months for patients with driver variations vs 40.1 months in patients without driver variations (log-rank P < .001). B, Median PFS time was 8.4 months for the non–KRAS driver mutation group, 8.0 months for the KRAS driver mutation group, and 40.1 months for the non-driver mutation group (log-rank P = .001). C, Median OS time was 36.2 months for those with driver variations and was not achieved in those without driver variations (log-rank P = .24).

Table 2. Multivariate Regression Analysis for Progression-Free Survival.

| Characteristic | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Mutation status | ||

| Non-driver | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Non-KRAS driver | 5.12 (2.21-11.86) | <.001 |

| KRAS driver | 5.79 (2.69-12.47) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Female | 0.6 (0.33-1.09) | .09 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Former or current | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Never | 0.93 (0.37-2.37) | .89 |

| Stage | ||

| IIB | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| IIIA | 0.92 (0.20-4.26) | .92 |

| IIIB | 2.97 (0.69-12.86) | .15 |

| IIIC | 7.88 (1.29-48.27) | .03 |

| Age | ||

| <65 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| ≥65 | 0.97 (0.54-1.75) | .93 |

| ECOG | ||

| 0-1 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 2 | 3.4 (1.35-8.53) | .009 |

| PD-L1 | ||

| Negative (0% TPS) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Low (1%-49% TPS) | 1.02 (0.42-2.48) | .96 |

| High (≥50% TPS) | 0.62 (0.22-1.71) | .35 |

| Not tested | 0.67 (0.26-1.75) | .42 |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Nonadenocarcinoma | 1.72 (0.91-3.27) | .10 |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PD-LI, antiprogrammed cell death ligand 1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

Because squamous histology may bias outcomes and variation testing on patients with NSCLC and squamous histology is not routinely performed at all institutions, we performed a subgroup analysis for all patients without nonsquamous histology. The subgroup analysis showed that driver variations still were associated with significantly worse PFS (median 8.5 months vs not achieved; HR, 4.49; 95% CI, 2.47-8.19; P < .001) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). There continued to be no significant difference in OS (median 36.2 months for drivers vs not achieved in nondrivers; HR, 2.16; 95% CI, 0.95-4.9; 1 P = .07) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Patterns of failure were not significantly different between patients with and without driver variations, with distant failures accounting for the majority of first progressions (23 [64%] vs 16 [59%]; P = .71) in both groups. Rates of oligometastatic progression (defined as 3 or fewer sites of progression) were also not significantly different (driver variations vs nondriver variations, 10 [28%] vs 13 [48%]; P = .12).

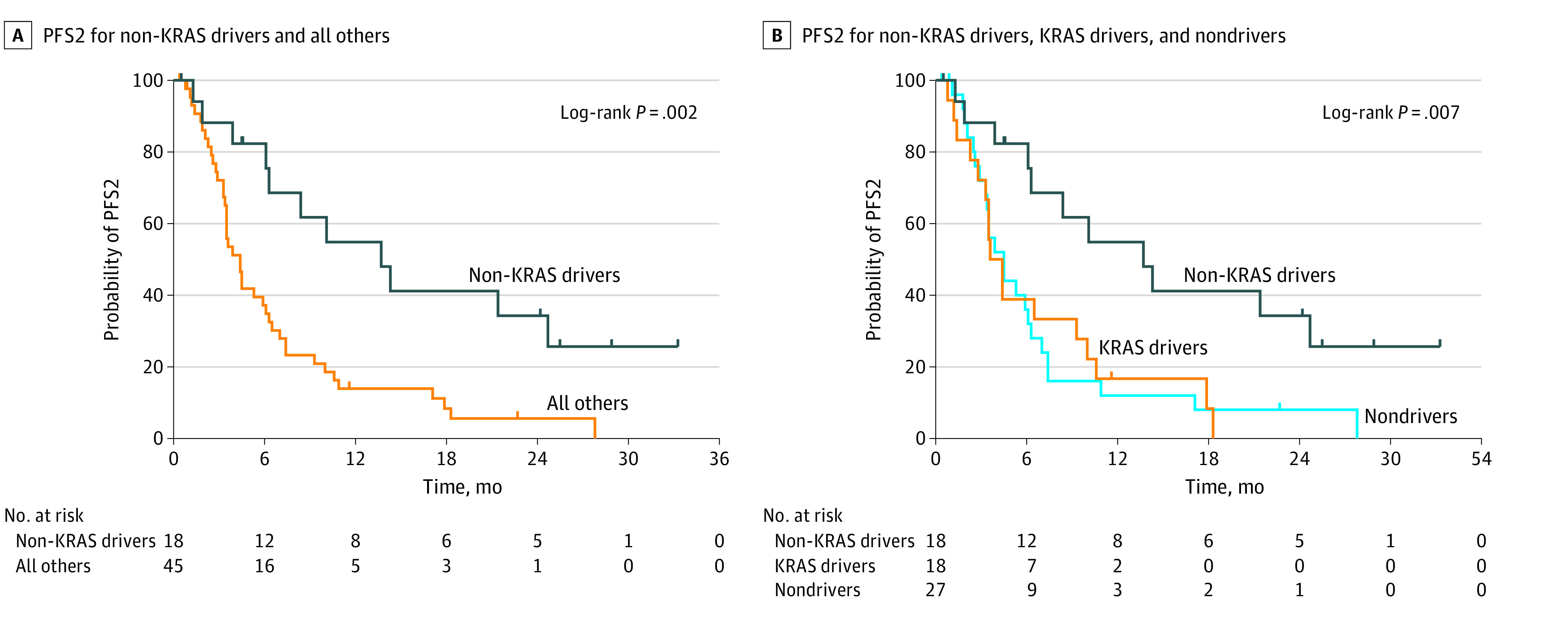

Time to Second Progression

We next addressed PFS2 for patients that progressed post-CRT and at least 1 cycle of durvalumab. Patients with non–KRAS driver variations had significantly longer PFS2 (median [IQR], 13.7 months [6.3 months to not achieved]) relative to all other patients (median [IQR], 4.4 [2.9-7.4] months) (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.64; P = .002) (Figure 2). For the multivariate analysis, non–KRAS driver variation was the only factor associated with improved PFS2 (eTable 2 in the Supplement). For the subgroup analysis of patients without squamous histology, non–KRAS driver variations was still associated with significantly longer PFS2 (median [IQR], 14.3 months [8.4 months to not achieved]) compared with all other patients (median [IQR], 3.9 [2.6-10.0] months) (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.17-0.64; P = .002) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). All patients with non–KRAS driver variations and 1 patient with KRAS G12C variation received TKI therapy as part of their postrelapse therapy with many receiving it as their first line of treatment (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Time to Second Progression (PFS2) in Patients With or Without Driver Variations Who Progressed After Definitive Chemoradiation and Consolidative Durvalumab.

A, Median time after the first episode of disease progression (PFS2) was 13.7 months for patients with non–KRAS driver variations vs 4.4 months for all other patients (log-rank P = .002). B, Median PFS2 time was 13.7 months for patients with non–KRAS driver variations, 4.0 months for patients with KRAS driver variations, and 4.5 months for patients without driver variations (log-rank P = .007).

Treatment-Related Toxic Effects

Rates and grades of toxic side effects are summarized in Table 3. The overall rate of grade 2 or higher toxic effects among all patients was 75%, with 23% experiencing grade 3 or higher toxic effects. The rates of both grade 2 or higher toxic effects (P = .78) and grade 3 or higher toxic effects (P = .77) did not differ by driver variation status.

Table 3. Treatment Toxic Effects by Variation Status.

| Toxic Effects | No. (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 104) | Non-KRAS driver variations (n = 21) | KRAS driver variations (n = 22) | Nondriver variations (n = 61) | ||

| All toxicities | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 78 (75.0) | 17 (81.0) | 17 (77.3) | 44 (72.1) | .78 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 24 (23.1) | 6 (28.6) | 5 (22.7) | 13 (21.3) | .77 |

| Pneumonitis | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 44 (42.3) | 13 (61.9) | 10 (45.5) | 21 (34.4) | .09 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 17 (16.3) | 4 (19.0) | 3 (13.6) | 10 (16.4) | .87 |

| Dysphagia | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 30 (28.8) | 4 (19.0) | 6 (27.3) | 20 (32.8) | .53 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | > .99 |

| Esophagitis | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 48 (46.2) | 9 (42.9) | 9 (40.9) | 30 (49.2) | .80 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.3) | > .99 |

| Pain | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 25 (24.0) | 4 (19.0) | 3 (13.6) | 18 (29.5) | .30 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 3 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.9) | .57 |

| Dermatitis | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 12 (11.5) | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.1) | 8 (13.1) | > .99 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 2 (1.9) | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 1 (1.6) | .41 |

| Arthritis | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 1 (1.0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | .202 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | > .99 |

| Diarrhea | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 2 (1.9) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.5) | 0 | .169 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 2 (1.9) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.5) | 0 | .17 |

| Anorexia | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 6 (5.8) | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 5 (8.2) | .62 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.6) | > .99 |

| Dehydration | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 3 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.9) | .57 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.6) | > .99 |

| Fatigue | |||||

| Grade 2 or higher | 9 (8.7) | 0 | 2 (9.1) | 7 (11.5) | .38 |

| Grade 3 or higher | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | > .99 |

Discussion

In this cohort study of patients with unresectable locally advanced NSCLC with driver variations, we found that the presence of a driver variation was associated with significantly worse PFS with the standard of care regimen of definitive chemoradiation and consolidative durvalumab, which is consistent with previous studies.1,2,3 We also found that for patients with targetable driver variations who progress, TKIs are an effective salvage regimen.

Our results lead to the question of why patients with locally advanced NSCLC with driver variations have such poor outcomes with the PACIFIC regimen. A possible explanation is that oncogene-driven NSCLC may have a smaller tumor mutation burden (TMB) compared with nondriver NSCLC given their addiction to particular signaling pathways. While an extensive analysis of TMB has not been performed across a large set of driver variations in NSCLC, a study has shown that EGFR-variant NSCLC has markedly lower TMB compared with EGFR-wildtype NSCLC.11 Lower TMB has been shown in multiple studies to predict worse outcomes on immune checkpoint inhibitors, including in the CheckMate 227 trial.12,13 This is possibly because of fewer immunogenic targets. More work remains to be done to explore the relationship between driver variations and TMB in NSCLC, which could potentially guide the future use of immunotherapy.

Several studies have assessed whether TKIs can improve clinical outcomes in patients with NSCLC with driver variations. A previous retrospective study3 reported significantly improved PFS among patients with EGFR-mutated stage III NSCLC who were given induction or consolidative EGFR TKI in conjunction with CRT compared with the PACIFIC regimen (26.1 months vs 10.3 months). The phase 3 ADAURA trial showed significantly improved disease-free survival with adjuvant osimertinib (89% vs 52%) in resected stage IB to stage IIIA EGFR-mutated NSCLC.14 The phase 3 LAURA trial is currently investigating consolidative osimertinib for patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC after CRT.15 However, use of TKIs in combination with immunotherapy must be pursued carefully given reports of increased toxic effects.16,17,18

Limitations

This study has limitations. A major limitation of our study was the small sample size and retrospective format from a single institution, which could carry some inherent biases to the outcomes and conclusion. Additionally, given the relatively recent adoption of consolidative durvalumab as the standard of care, our cohort has relatively short follow-up time and immature OS data. Despite these limitations, our study is one of the largest assessments of the effectiveness of the PACIFIC regimen in unresectable locally advanced NSCLC patients with driver variations.

Conclusions

The findings of this cohort study highlight the prognostic importance of assessing gene variation status in unresectable locally advanced NSCLC patients in guiding treatment decisions. Our data suggest the need for future clinical trials to test the potential benefit of replacing or combining durvalumab with TKI therapy for patients with driver variations.

eTable 1. Variations and Salvage Therapies of All Patients

eTable 2. Multivariate Regression Analysis for Time to Second Progression

eFigure 1. Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS) for Nonsquamous NSCLC Patients With or Without Driver Variations Treated With Definitive Chemoradiation and Consolidative Durvalumab

eFigure 2. Time to Second Progression (PFS2) in Non-Squamous Patients With or Without Driver Variations Who Progressed After Definitive Chemoradiation and Consolidative Durvalumab

References

- 1.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. ; PACIFIC Investigators . Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1919-1929. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faivre-Finn C, Vicente D, Kurata T, et al. Four-year survival with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in state III NSCLC – an update from the PACIFIC trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(5):860-867. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aredo JV, Mambetsariev I, Hellyer JA, et al. Durvalumab for stage III EGFR-mutated NSCLC after definitive chemoradiotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(6):1030-1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.01.1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Negrao MV, Skoulidis F, Montesion M, et al. Oncogene-specific differences in tumor mutational burden, PD-L1 expression, and outcomes from immunotherapy in non–small cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(8):e002891. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-002891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazieres J, Drilon A, Lusque A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(8):1321-1328. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong DS, Fakih MG, Strickler JH, et al. KRASG12C inhibition with sotorasib in advanced solid tumors. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(13):1207-1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2371-2381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al. ; WHO Panel . The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of lung tumors: impact of genetic, clinical, and radiographic advances since the 2004 classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(9):1243-1260. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Kim AW, Tanoue LT. The eighth edition lung cancer stage classification. Chest. 2017;151:193-203. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Offin M, Rizvi H, Tenet M, et al. Tumor mutation burden and efficacy of EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(3):1063-1069. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology: mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124-128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2093-2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, et al. ; ADAURA Investigators . Osimertinib in resected EGFR-mutated non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(18):1711-1723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu S, Casarini I, Kato T, et al. Osimertininb maintenance after definitive chemoradiation in patients with unresectable EGFR mutation positive stage III non–small-cell lung cancer: LAURA trial in progress. Clin Lung Cancer. 2021;22(4):371-375. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2020.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oshima Y, Tanimoto T, Yuji K, Tojo A. EGFR-TKI-associated interstitial pneumonitis in nivolumab-treated patients with non–small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(8):1112-1115. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoenfeld AJ, Arbour KC, Rizvi H, et al. Severe immune-related adverse events are common with sequential PD-(L)1 blockade and osimertinib. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(5):839-844. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garassino MC, Cho BC, Kim JH, et al. Final overall survival and safety update for durvalumab in third- or later-line advanced NSCLC: the phase II ATLANTIC study. Lung Cancer. 2020;147:137-142. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Variations and Salvage Therapies of All Patients

eTable 2. Multivariate Regression Analysis for Time to Second Progression

eFigure 1. Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS) for Nonsquamous NSCLC Patients With or Without Driver Variations Treated With Definitive Chemoradiation and Consolidative Durvalumab

eFigure 2. Time to Second Progression (PFS2) in Non-Squamous Patients With or Without Driver Variations Who Progressed After Definitive Chemoradiation and Consolidative Durvalumab