Introduction

Point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) is a clinician-performed limited ultrasound study used to answer focused clinical questions at the bedside. POCUS in nephrology is no longer confined to kidney ultrasound or procedural guidance but encompasses a wide range of applications, including lung ultrasound and limited echocardiography for fluid status assessment.1,2 When evaluating a patient with acute kidney injury (AKI), it is important to systematically rule out the potential causes by careful history taking, physical examination, and analysis of laboratory data. POCUS is an adjunct to physical examination and aids in the diagnosis and management of AKI from excluding hydronephrosis to providing real-time insights into hemodynamic status. In this case study, we describe how POCUS was used to monitor the efficacy of decongestive therapy in a patient with AKI and hypervolemia.

Case Presentation

A 37-year-old man with a history of quadriplegia and chronic hypoxic respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation via tracheostomy was admitted to the intensive care unit for the management of pneumonia. Serum creatinine level at presentation was 1.39 mg/dl (reference range: 0.7–1.3; baseline 0.6 before admission), and chest imaging result was suggestive of multifocal pneumonia. He progressed to acute respiratory distress syndrome with septic shock over the next few days requiring vasopressor therapy and worsening oxygen requirement. The test result for novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 was negative. Serum creatinine level worsened to 3.3 mg/dl with a decline in urine output. A renal sonogram was obtained, which excluded obstructive uropathy. Fractional excretion of urea was 25.6%, suggestive of prerenal etiology, which prompted the clinician to think about intravascular volume depletion. Of note, the patient was being treated with diuretics because of the increased extravascular lung water. A bolus of i.v. fluid was administered, and nephrology consultation was requested for further input on AKI. Furthermore, question was posed about possible glomerulonephritis and pulmonary-renal syndrome because the antinuclear antibody test result was positive (1:160, speckled pattern); however, bronchoscopy was equivocal for alveolar hemorrhage.

Nephrology Evaluation

At the time of evaluation, the patient on mechanical ventilation had a fraction of inspired oxygen of 70% and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 12 cm H2O. Blood pressure was 96/53 mm Hg, pulse rate 92 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation 90%. Physical examination was significant for bilateral lung crackles and trace pitting pedal edema. Recorded urine output was approximately 350 ml in the past 24 hours. Urine microscopy results demonstrated muddy brown casts suggestive of tubular injury; no dysmorphic red blood cells were seen. Notably, this does not exclude ongoing hemodynamic injury. In addition to elevated serum creatinine levels, laboratory data were significant for mild hypernatremia (serum sodium 146 mmol/l), hyperkalemia (serum potassium 5.9 mmol/l), and a serum bicarbonate of 25 mmol/l. These findings together with a low fractional excretion of urea mentioned before can be seen in dehydration and intravascular volume depletion from overdiuresis. A common approach to this constellation of clinical and laboratory findings would be to empirically administer fluids. We performed bedside ultrasound to see if the patient’s physiology corroborated the use of further fluids.

POCUS Findings

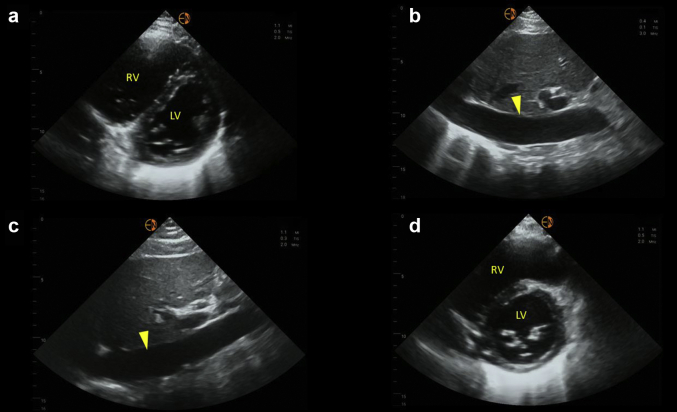

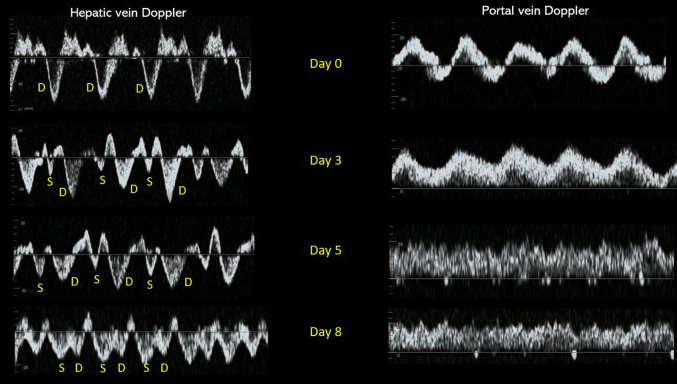

Lung ultrasound revealed bilateral diffuse B-line pattern with irregular pleural line consistent with known acute respiratory distress syndrome. Focused cardiac ultrasound revealed hyperdynamic left ventricular systolic (S) function and an enlarged right ventricle. Interventricular septal flattening was noted, making the left ventricle look like letter “D” instead of normal circular appearance (D-sign) in short axis, suggestive of volume and/or pressure overload (Figure 1a). This could have been contributing to decreased cardiac output by compromising the left ventricular outflow and thus low blood pressure. Inferior vena cava (IVC) was plethoric (Figure 1b); however, IVC-estimated right atrial pressure (RAP) is unreliable in mechanically ventilated patients. Moreover, our patient was chronically ventilator dependent. Hepatic and portal vein Doppler was performed to assess venous congestion. Hepatic vein Doppler waveform revealed S-wave reversal (above the baseline) with a predominantly diastolic (D) pattern suggestive of severely elevated RAP level. Normal hepatic flow consists of both S- and D-waves below the baseline with S > D pattern. Similarly, portal vein Doppler waveform was pulsatile with intermittent flow reversal suggesting severe venous congestion. Normal portal vein waveform is relatively continuous, above the baseline. Overall, POCUS findings indicated severely elevated extravascular lung water, right ventricular enlargement, and severe systemic venous congestion.

Figure 1.

Sonographic findings at the time of nephrology consult (day 0) and day 8. (a) Parasternal short-axis view of the heart demonstrating interventricular septal flattening with D-shaped left ventricle on day 0. (b) Plethoric IVC on day 0. (c) Relatively unchanged IVC on day 8. (d) Normal-appearing left ventricle on day 8. Arrowhead in panels b and c points to IVC. IVC, inferior vena cava; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Management

Based on the clinical, laboratory, and imaging data, the patient was started on continuous renal replacement therapy to facilitate fluid removal and aid renal recovery by addressing ongoing hemodynamic insult. Results of anti–double-stranded DNA, antiglomerular basement membrane, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies came back negative, and thus renal biopsy was not considered.

Follow-Up

At our institution, we use POCUS parameters to guide decongestive therapy in complex cases such as this.3,4 On day 3 after initiating continuous renal replacement therapy (day 0), documented fluid balance was negative 6.6 l. Hepatic vein Doppler showed S-wave below the baseline (but S < D), and portal vein pulsatility improved consistent with improving congestion. Blood pressure was 115/57 mm Hg without vasopressors. We continued ultrafiltration. On day 5, fluid balance was negative 5.1 l compared with that on day 3. Hepatic vein Doppler was similar to previous tracing, but the portal vein waveform normalized suggesting further improvement in venous congestion. Urine output was 150 ml in the previous 24 hours. At this point, we discontinued continuous renal replacement therapy with a plan to transition to intermittent hemodialysis. Generally, portal vein waveform improves before hepatic as it is separated from IVC flow by hepatic sinusoids that prevent direct transmission of RAP.5 In most cases, we use normalization of portal Doppler as an indicator of improved renal perfusion.6,7 However, the patient made more urine overnight (∼600 ml) and did not require hemodialysis. On day 8, fluid balance was negative 2 l compared with that on day 5. Hepatic vein Doppler normalized with S > D pattern and that of portal vein remained normal suggestive of resolved venous congestion. Although IVC remained dilated, it is most likely a chronic finding in this patient (Figure 1c). Lung ultrasound showed improvement though the findings of increased lung water did not resolve completely. Interestingly, D-sign on cardiac ultrasound disappeared with return of left ventricle to its normal circular shape (Figure 1d), indicating resolution of the effect of volume overload on the right ventricle. Serum creatinine level at that time was 2.1 mg/dl, which eventually trended down to 0.6 mg/dl (baseline) a week later. Table 1 and Figure 2 summarize these findings.

Table 1.

Pertinent parameters on the days of ultrasound follow-up mentioned in the text

| Day | Documented fluid balance (l) | IVC | Hepatic vein Doppler | Portal vein Doppler | 24-h urine output (ml) | Renal replacement therapy status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Positive 2 l from 2 d prior | Plethoric | S-reversal | Pulsatile with flow reversal | 350 | CRRT initiated |

| 3 | Negative 6.6 l from day 0 | Plethoric | S < D | Pulsatile without flow reversal | 20 | CRRT continued |

| 5 | Negative 5.1 l from day 3 | Plethoric | S < D | Continuous (normal) | 150 | CRRT stopped |

| 8 | Negative 2 l from day 5 | Plethoric | S > D (normal) | Continuous | 1565 | No RRT |

CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; D, diastolic; S < D, amplitude of the S-wave is lesser than that of D-wave; S > D, amplitude of S-wave greater than D-wave; S, systolic.

Figure 2.

Transition of hepatic and portal vein Doppler waveforms with fluid removal indicating improvement in venous congestion from day 0 to day 8. D, diastolic; S, systolic.

Discussion

Evaluation and management of AKI are like solving a puzzle that involves putting together several pieces of data. Over-reliance on 1 piece can lead to mismanagement or omission of ongoing insults. For example, documented fluid balance and weight are not always accurate. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination findings such as pedal edema, rales, and jugular venous distension is limited.8,9 Laboratory data can be misinterpreted when clinical scenario is ambiguous. In our patient, low fractional excretion of urea was initially thought to indicate intravascular volume depletion. In reality, it can be low in both volume depletion and volume excess. Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity of fractional excretion of urea in distinguishing between prerenal AKI and tubular injury are only modest.S1 Adding to the problem, the effect of hypervolemia/venous congestion on renal perfusion is under-recognized. Global renal perfusion pressure is the difference between inflow and outflow pressures, which are mean arterial pressure and RAP, respectively.S2,S3 As such, elevated RAP level causes impaired renal perfusion, and it is vital to detect hemodynamic aberrations in a timely manner. Multiorgan POCUS may offset some of the limitations discussed previously if properly integrated into overall clinical picture. Missing the clinical context or solely relying on individual components of POCUS can again lead to suboptimal patient management. For instance, our patient was on chronic mechanical ventilation, and hence, IVC was less reliable to estimate RAP. Similarly, novice POCUS users can reflexively attribute hyperdynamic left ventricle to hypovolemia despite the fact that it can be seen in multiple other scenarios such as reduced afterload as in vasoplegia, mitral regurgitation, or right ventricular dysfunction. Doppler evaluation of the abdominal veins has recently evolved as an adjunct to IVC ultrasound for gauging the downstream effects of elevated RAP level and monitor the response to decongestive therapy as demonstrated in our case. Supplementary Figure S1 illustrates the transition of Doppler waveforms with changes in RAP and venous excess ultrasound grading protocol. Note that although the grading system involves the renal parenchymal vein Doppler in addition to hepatic and portal veins, demonstration of severe flow abnormalities in 2 of these veins is sufficient to document severe congestion and predict renal injury.S4

Conclusion

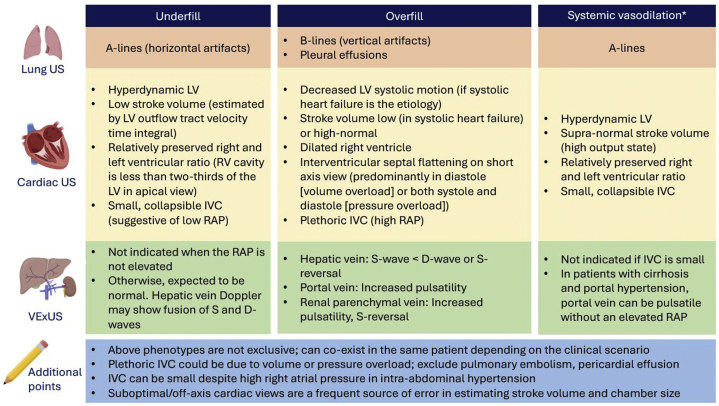

In summary, nephrologist-performed multiorgan POCUS enhances the diagnostic accuracy and guides therapy when interpreted in conjunction with clinical and laboratory data. Future studies are needed to evaluate whether this integrative approach portends any beneficial effect on measurable patient outcomes. The key take-home points from our case are summarized in Table 2. In addition, Figure 3 provides an overview of POCUS findings in common hemodynamic phenotypes encountered in nephrology practice.

Table 2.

Teaching points

|

|

|

Figure 3.

Overview of common sonographic findings in nephrology-relevant hemodynamic phenotypes. ∗Systemic vasodilation is frequently seen in patients with liver cirrhosis or early sepsis and renal dysfunction. Underfill phenotype primarily denotes volume depletion. IVC, inferior vena cava; LV, left ventricle; RAP, right atrial pressure; US ultrasound; VExUS, venous excess Doppler ultrasound.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Patient Consent

The patient’s next of kin provided consent to publish this case study.

Data Sharing Statement

The data sets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for single case study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

ATA participated in patient care and drafted the initial version. AK supervised the ultrasound studies and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Both the authors provide approval for publication of the content.

Footnotes

Figure S1. Venous excess ultrasound (VExUS) grading.

Supplementary References.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Venous excess ultrasound (VExUS) grading.

Supplementary References.

References

- 1.Reisinger N., Koratala A. POCUS for nephrologists: basic principles and a general approach. Kidney360. 2021;2:1660–1668. doi: 10.34067/KID.0002482021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koratala A., Olaoye O.A., Bhasin-Chhabra B., Kazory A. A blueprint for an integrated point-of-care ultrasound curriculum for nephrology trainees. Kidney360. 2021;2:1669–1676. doi: 10.34067/KID.0005082021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koratala A., Kazory A. Point of care ultrasonography for objective assessment of heart failure: integration of cardiac, vascular, and extravascular determinants of volume status. Cardiorenal Med. 2021;11:5–17. doi: 10.1159/000510732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh S., Koratala A. Utility of Doppler ultrasound derived hepatic and portal venous waveforms in the management of heart failure exacerbation. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:1489–1493. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lautt W.W., Greenway C.V. Conceptual review of the hepatic vascular bed. Hepatology. 1987;7:952–963. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaubien-Souligny W., Eljaiek R., Fortier A., et al. The association between pulsatile portal flow and acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32:1780–1787. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eljaiek R., Cavayas Y.A., Rodrigue E., et al. High postoperative portal venous flow pulsatility indicates right ventricular dysfunction and predicts complications in cardiac surgery patients. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson L.W., Perloff J.K. The limited reliability of physical signs for estimating hemodynamics in chronic heart failure. JAMA. 1989;261:884–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martindale J.L., Wakai A., Collins S.P., et al. Diagnosing acute heart failure in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:223–242. doi: 10.1111/acem.12878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.