Abstract

Background

Rates of preterm birth are substantial with significant inequalities. Understanding the role of risk factors on the pathway from maternal socioeconomic status (SES) to preterm birth can help inform interventions and policy. This study therefore aimed to identify mediators of the relationship between maternal SES and preterm birth, assess the strength of evidence, and evaluate the quality of methods used to assess mediation.

Methods

Using Scopus, Medline OVID, “Medline In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citation”, PsycINFO, and Social Science Citation Index (via Web of Science), search terms combined variations on mediation, socioeconomic status, and preterm birth. Citation and advanced Google searches supplemented this. Inclusion criteria guided screening and selection of observational studies Jan-2000 to July-2020. The metric extracted was the proportion of socioeconomic inequality in preterm birth explained by each mediator (e.g. ‘proportion eliminated’). Included studies were narratively synthesised.

Results

Of 22 studies included, over one-half used cohort design. Most studies had potential measurement bias for mediators, and only two studies fully adjusted for key confounders. Eighteen studies found significant socioeconomic inequalities in preterm birth. Studies assessed six groups of potential mediators: maternal smoking; maternal mental health; maternal physical health (including body mass index (BMI)); maternal lifestyle (including alcohol consumption); healthcare; and working and environmental conditions. There was high confidence of smoking during pregnancy (most frequently examined mediator) and maternal physical health mediating inequalities in preterm birth. Significant residual inequalities frequently remained. Difference-of-coefficients between models was the most common mediation analysis approach, only six studies assessed exposure-mediator interaction, and only two considered causal assumptions.

Conclusions

The substantial socioeconomic inequalities in preterm birth are only partly explained by six groups of mediators that have been studied, particularly maternal smoking in pregnancy. There is, however, a large residual direct effect of SES evident in most studies. Despite the mediation analysis approaches used limiting our ability to make causal inference, these findings highlight potential ways of intervening to reduce such inequalities. A focus on modifiable socioeconomic determinants, such as reducing poverty and educational inequality, is probably necessary to address inequalities in preterm birth, alongside action on mediating pathways.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-022-13438-9.

Keywords: Preterm birth, Mediation, Socioeconomic inequalities, Maternal smoking, Causal inference

Background

Preterm birth, defined as birth before 37 weeks’ gestation, is a substantial public health problem, accounting for nearly 11% of births globally. Prevalence varies across regions and is increasing in most countries [1]. Inequalities on the basis of various individual and area level measures of maternal socioeconomic status (SES) are consistently demonstrated [2], with estimates from Europe indicating an almost 50% higher prevalence among the least compared with most educated mothers [3, 4], and a substantial proportion of negative perinatal outcomes is attributed to socioeconomic inequalities [5].

Preterm birth has serious negative health, educational, and social outcomes [6] and is a leading cause of mortality in children under five. Therefore, understanding how to reduce inequalities in preterm birth represents a clear policy aim for reducing health inequalities more broadly. For example, studies have shown that preterm birth is an important driver of inequalities in child mortality, mental health, asthma and obesity [1, 7, 8].

Studies of socioeconomic inequalities in preterm birth have indicated that maternal factors on the causal pathway from maternal SES to preterm birth may partly explain inequalities, however the impact of these factors is unclear [9]. These intermediate maternal factors, or mediators, include known risks for preterm birth: smoking during pregnancy, low or high body mass index (BMI), and poor pre-pregnancy maternal health [10–12]. These risks, and other health system factors, such as access to antenatal care, are potential contributors to differences in preterm birth between groups [13] and are socially patterned.

A potentially effective way to reduce inequalities in preterm birth is through intervention on mediating pathways linking maternal SES and risk of preterm birth. Mediation is the mechanism whereby an exposure affects an outcome indirectly through a third variable that sits on the causal pathway from exposure to outcome. There has been rapid development of methods to assess mediation in observational data over the last ten years. These methods have increased our ability to make causal interpretations under specific assumptions, using the counterfactual framework [14]. The assumptions are that: a) there is no unmeasured confounding of exposure-outcome, exposure-mediator, and mediator-outcome pathways and b) no confounder of the mediator-outcome pathway is also caused by the exposure (‘cross-world independence’).

The evidence for mediation of socioeconomic inequalities in preterm birth has not, however, been systematically assessed in the context of these new advances. This review therefore aims to identify mediators of the relationship between maternal SES and preterm birth, assess the strength of evidence, and evaluate the quality of methods used to assess mediation.

Methods

This review sought empirical studies published between January 2000 and July 2020 that address the research question: ‘How do key risk factors, such as maternal health, maternal behaviours, and system-level factors, mediate the effect of maternal socioeconomic status on preterm birth?’. The protocol was registered with the Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Registration code: PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020203613). Ethics approval was not required. Reporting complies with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance (as per PRISMA statement, Additional file 1). Minor deviations from the PROSPERO protocol (as detailed in Additional file 2) have not impacted on our findings or introduced a new risk of bias.

Search strategy

Searches used five databases: Scopus, Medline OVID, “Medline In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citation”, PsycINFO and Social Science Citation Index (via Web of Science). Search terms were informed by an existing systematic review for mediation [15] and followed the PICO structure (Table 1). Searches were supplemented using the same search terms through Advanced Google Searches. Search terms combined variations on mediation, SES, and preterm birth (Additional file 3).

Table 1.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria for systematic review

| Include | Exclude | |

| Population | Pregnant women | |

| Intervention / mediator | Behavioural risk factors (e.g. smoking, alcohol). Social risk factors (e.g. Environmental (housing, working)). Maternal health status (both mental and physical health) | Genetic risks for preterm birth |

| Comparison across exposure | Comparison across socioeconomic strata (either individual or area-based) | |

| Outcomes | Preterm birth and gestational age | Other birth outcomes (e.g. low birthweight) |

| Publication characteristics: Inclusion / exclusion criteria | ||

| Include | Exclude | |

| Publication types | Primary studies from peer-reviewed literature, including those from reviews. Relevant secondary analyses (meta-analysis). Papers published or in-press. Working papers | Not primary research, e.g. letters, editorials, commentaries, conference proceedings, books and book chapters, meeting abstracts, lectures, and addresses. Previous reviews and meta-analyses, but relevant reviews were used to identify relevant primary studies |

| Types of study |

Analytical techniques that are relevant to research question: --Mediation --Attenuation Differential exposure |

Other methods. Mediation or attenuation not specifically calculated within analysis |

| Year of publication | 2000–2020 | |

| Language | English language | |

Different measures of SES (e.g. parental education, occupation, income and neighbourhood factors) were all included. Maternal SES can be used to measure inequalities in broadly two ways; individual or area-based measures. Individual measures include educational attainment, income, and occupation, and may be further classified as measures for the mother and for the household (e.g. for income). Area-based measures can include census tracts or composite scores for deprivation and are frequently used as a proxy measure for individual SES.

The starting time period cut-off of 2000 was used as the focus of the review was on the application of recent advancements in mediation analysis techniques to the evidence base. Therefore, studies before 2000 would not be relevant.

All included studies were hand-searched for backward citations (using reference lists) and forward citations (using Web of Science). Studies included in relevant systematic reviews identified were also assessed [16–23]. Screening used EPPI-Reviewer 4 systematic review management software [24].

Selection

On screening titles and abstracts, those mentioning mediation or explanation of inequalities in preterm birth were then reviewed against the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 1). Approximately 15% of titles-abstracts were dual-screened and calibrated to ensure consistent screening. The remaining titles-abstracts were single-screened. Included papers underwent full-text screening independently by two reviewers. A third reviewer was available to settle remaining disagreements but was not needed. All study designs were included.

Data extraction

All data were dual-extracted independently by two reviewers. Data extracted included study design, population, time period, sample size, measure of maternal SES, mediators examined, mediation analysis approach, total effect of SES on preterm birth, indirect effect through the mediator, significance of pathways, and proportion eliminated through mediation (the standardised metric used in synthesis, Table 2) [25]. For studies not providing proportion eliminated, it was estimated by dividing the indirect effect via the mediator by the total effect. Significance of mediation was assessed using the indirect effect confidence intervals (CI) primarily, if available, or the p value of the effect. Proportion eliminated was selected to synthesise the range and distribution of mediated effects [25]. Meta-analysis was not appropriate because the mediators investigated and methods of calculating mediation effects differed between studies, and many studies lacked significance estimates.

Table 2.

Description of mediation effects

| Effect Measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Total Effect |

The overall effect of the exposure on an outcome: --For the difference method, this is the regression output for the exposure when not adjusted for the mediator. --For product of coefficients, this is the sum of direct and indirect effect |

| Direct Effect | The effect of the exposure on an outcome when the intermediate variable is removed |

| Indirect Effect | The effect of the exposure on an outcome through an intermediate variable |

| Proportion Eliminated |

How much of the total effect would be removed through action on the intermediate variable (setting the mediator to the same level for all pregnant women) [26]: --For the difference method, this is the difference between the total effect and regression output for the mediator-adjusted regression, divided by total effect (minus one if using exponentiated outputs) --For product of coefficients, this is the indirect effect divided by total effect [14] |

Quality-scoring

Studies were quality-assessed using a hybrid approach. This assessed study quality through the risk of bias and the quality of the mediation methods used (Additional file 4). Risk of bias associated with study design was assessed using the Liverpool University Quality Assessment Tool relevant to the particular study design [27]. Given that there is no standard approach for quality assessment of mediation analyses, we added three criteria based on a previous mediation review and on qualitative work informing reporting guidelines for studies of mediation [15, 28]. Aspects of study design relevant to mediation analysis included: consideration of exposure-mediator interaction in the analysis; a directed acyclic graph (DAG) [29] informing the mediation analysis; and consideration of causal assumptions underpinning the mediation analysis.

Integration

Studies were synthesised narratively, and results were grouped by mediator. The order of reporting results in text was based upon frequency of the mediator in the included studies and the quality-scoring [30, 31]. The certainty of the evidence for each mediator was assessed by considering the sample size, quality score, and consistency of the direction of mediated effects (GRADE). Criteria for publication bias and imprecision could not be calculated [25]. A harvest plot displayed the range of proportion eliminated for the four most studied mediators [32]. Results from the review were then used to identify mediators and confounders, which were integrated into a DAG [29].

Results

Search results and description of included studies

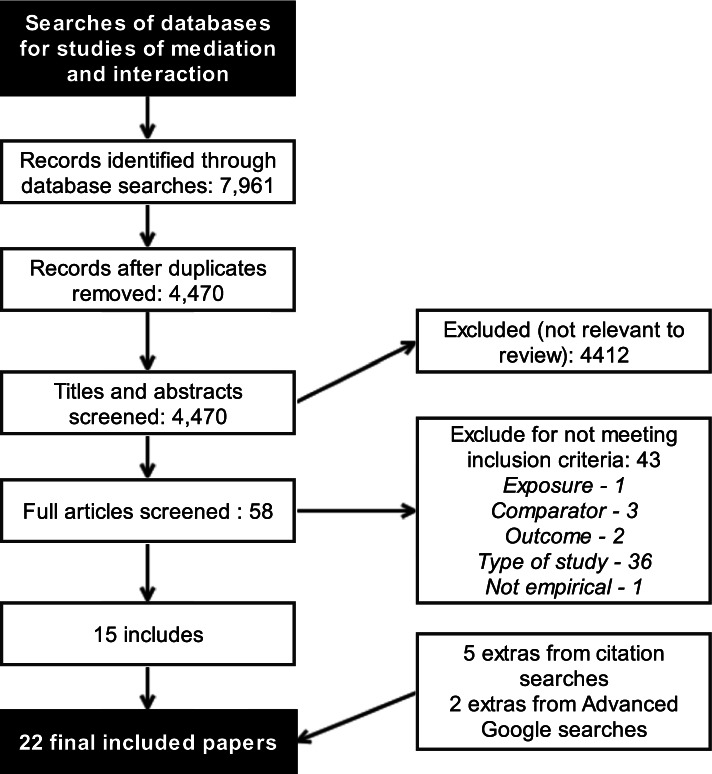

After removing duplicates, the initial searches identified 4,470 papers to review, of which 58 were full-text screened (Fig. 1). After screening and citation searches, 22 studies were included [33–54]. Over half of the studies used cohort design. Ten were from Europe (all North and West Europe) [33, 43, 46–53], eight were from North America (six from USA, two from Canada) [34, 36–39, 41, 42, 44], two from Iran [35, 40], and one each from Ghana [45] and Brazil (Table 3) [54]. One study did not specify the study period, and the other 21 covered periods between 1980 and 2013. Another excluded study did not quantify results for the mediation of the SES effect on preterm birth by smoking [55]. Only one study provided the CI for the proportion eliminated [33].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram for included studies for the systematic review question

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 22) about mediation between socioeconomic status (SES) and preterm birth

| Paper | Design | Country | Sample Size and Characteristics | Study Period | Mediation Analysis Approach | Measure of SES | Quality Score (/13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poulsen et al. (2019) [33] | Cohort | Denmark | 77,020 – National birth cohort (whole) | NS | Difference method using risk differences from linear regression | Maternal education: Short (≤ lower secondary) to long (degree; reference) | 10 |

| Netherlands | 4,508 – Rotterdam birth cohort (whole) | NS | |||||

| Norway | 78,267 – National birth cohort (whole) | NS | |||||

| Ross et al. (2019) [34] | Cohort | United States (US) | 718,952 –Californian birth cohort (whole) | 2007–2012 | Product of coefficients/ Path analysis using Lavaan Package | Maternal education: At most high-school to more than high school (reference) | 9 |

| Dolatian et al. (2014) [35] | Cohort | Iran | 500 – Random sample of pregnant women from stratified sample of four Tehran hospitals | 2011–2012 | Product of coefficients/ Path analysis using Lisrel Software | Income | 9 |

| Clayborne et al. (2017) [36] | Cohort | Canada | 2,068 – Sample of pregnant women from Calgary and Edmonton Metropolitan Regions | 2008–2012 | Product of coefficients using PROCESS macro | Neighbourhood SES | 8 |

| Dooley (2009) [37] [PhD thesis] | Cross-sectional | US | 28,793 – Hamilton County, Ohio, birth cohort (whole) | 2001–2003 | Product of coefficients/ Path analysis of multilevel modelling using Mplus | Neighbourhood concentrated disadvantage | 8 |

| Mehra et al. (2019) [38] | Cohort | US | 138,494 – National convenience sample (retrospective) of births from all states using health insurance data | 2011 | Product of coefficients/ Path analysis of multilevel modelling using Mplus | Neighbourhood SES: most deprived quarter to least deprived (reference) | 8 |

| Meng et al. (2013) [39] | Cross-sectional | Canada | 90,500—All births (including multiple) at three Ontario province public health units | 2000–2008 | Product of coefficients of multilevel modelling using both linear and logistic regression | Neighbourhood SES | 8 |

| Mirabzadeh et al. (2013) [40] | Cohort | Iran | 500 – Random sample of pregnant women from stratified sample of four Tehran hospitals | 2012–2013 | Product of coefficients/ Path analysis using Lisrel Software | Composite comprising: maternal and spousal education, persons and cost/household area, car, computer | 8 |

| Misra et al. (2001) a[41] | Cross-sectional | US | 735 – Urban university hospital sample of births to black mothers: drug users, women without prenatal care, and a systematic sample of the rest | 1995–1996 | Difference method using logistic regression | Lack of time and money | 8 |

| Nkansah-Amankra et al. (2010) [42] | Cross-sectional | US | 8,064 – South Carolina state, stratified systematic sample of births | 2000–2003 | Difference method using multilevel logistic modelling | Neighbourhood SES: Proportion of residents in poverty | 8 |

| Räisänen et al. (2013) [43] | Cross-sectionalb | Finland | 1,390,742 – National birth cohort (whole) | 1987–2010 | Difference method using logistic regression | Maternal occupation; blue collar relative to upper white collar (reference) | 8 |

| Ahern et al. (2003) [44] | Case–Control | US | 1,496 cases + controls – A San Francisco hospital based sample of births: All preterm plus random selections of full-term, stratified by African American and White | 1980–1990 | Difference method using multilevel logistic modelling | Neighbourhood context | 7 |

| Amegah et al. (2013) [45] | Cross-sectional | Ghana | 559 – Cape Coast’s four main healthcare facilities, random sample weighted by hospital or urban centre | 2011 | Difference method: Generalised linear model using Poisson Distribution and log link | Level of monthly income: low to upper middle and high (reference) | 7 |

| van den Berg et al. (2012) [46] | Cohort | Netherlands | 3,821 – Amsterdam birth cohort (Dutch-only) (whole) | 2003–2004 | Difference method using logistic regression | Maternal education: years of education after primary school, low (< 6) to high (> 10; reference) | 7 |

| Morgen et al. (2008) [47] | Cohort | Denmark | 38,131 primiparous & 37,849 multiparous – National birth cohort | 1996–2002 | Difference method using Cox regression | Maternal education; < 10 years to > 12 years (reference) | 7 |

| Gisselmann and Hemström (2008) [48] | Cross-sectional | Sweden | 356,887 – National birth cohort (whole) | 1980–1985 | Difference method using logistic regression | Maternal occupation: Unskilled manufacturing manuals to middle non-manuals (reference) | 7 |

| Niedhammer et al. (2012) [49] | Cohort | Republic of Ireland | 913 – Random sample of pregnant women (Irish-only) from two hospitals (urban and rural) | 2001–2003 | Difference method using Cox Regression | Maternal education: lower than to higher than secondary (reference) | 7 |

| Jansen et al. (2009) [50] | Cohort | Netherlands | 3,830 – Rotterdam birth cohort (whole) | 2002–2006 | Difference method using logistic regression | Maternal education: low (< 4 years general secondary) to high (Master degree, PhD; reference) | 7 |

| Quispel et al. (2014) a[51] | Cohort | Netherlands | 1,013 – Rotterdam, Apeldoorn, Breda: Random samples of pregnant women from primary, secondary, tertiary care | 2009–2011 | Difference method using logistic regression | Maternal education: low to moderate (reference) | 6 |

| Gissler et al. (2003) [52] | Cross-sectional | Finland | 548,913 – National birth cohort (whole) | 1991–1999 | Difference method using logistic regression | Maternal occupation: blue collar to upper white collar (reference) | 6 |

| Gray et al. (2008) [53] | Cohort | Scotland | 400,752 – National (hospital) birth cohort (whole) | 1994–2003 | Difference method using logistic regression | Neighbourhood SES: most deprived fifth to least deprived (area-based) (reference) | 6 |

| de Oliveira et al. (2019) [54] | Case–Control | Brazil | 296 cases + 329 controls – Londrina sample of hospital births (including multiple) | 2006–2007 | Structural equation modelling | Socioeconomic vulnerability | 4 |

NS not stated

a Not specified if Misra et al. (2001) [41] and Quispel et al. (2014) [51] excluded multiple births. Meng et al. (2013) [39] and de Oliveira et al. (2019) [54] included multiple births. All other studies excluded multiple births

b despite being labelled as a case–control study

Ordered by Quality Score

Quality assessment

Additional file 5 shows the quality-scoring for each study. In all the cohort studies there was risk of either selection bias (4/12) [34, 36, 38, 46], response bias (6/12) [35, 40, 49–51, 53], or bias in follow-up (3/12) [33, 47, 51]. Of the two case-control studies, one had a risk of bias in selection of both cases and controls [54]. Of the cross-sectional studies, three showed low risk of bias, but the others showed potential selection bias (1/8) [52] and response bias (4/8) [37, 39, 41, 45].

Fifteen studies used individual measures of maternal SES, and seven used aggregated measures (e.g. neighbourhood SES) [36–39, 42, 44, 53]. Potential measurement bias for the mediators featured in 14 studies (mostly from self-reported smoking) [33, 37, 39, 42–50, 52, 53], while nine explained measurement of preterm birth inadequately [34, 36, 38, 39, 44, 48, 51, 52, 54]. Of the three confounders identified (maternal age, parity, and race or ethnicity – see below), three studies adjusted for none [40, 51, 54], 17 adjusted for one or two [33, 35, 37–39, 41–50, 52, 53], and two adjusted for all three variables [34, 36].

Mediation approach

The ‘difference method’ was the most frequently used approach to assess mediation (14 studies) [33, 41–53], estimating the ‘controlled direct effect’ [14]. Other approaches used product of coefficients (seven, with path analysis in five) [34–40] and, in one, structural equation modelling not specified as path analysis [54]. Only one of the studies using the difference method estimated the statistical significance of the mediating effect, using bootstrapping to estimate CI [33].

Regarding quality of mediation analysis: 11 studies included graphical representation (DAG) of the mediated pathway [33–41, 51, 54], six studies examined exposure-mediator interaction in their analysis [33, 37–39, 42, 44], and only two studies explicitly considered the causal assumptions; these studies included all three of these quality indicators [33, 39]. The temporal nature of measurement of exposure and outcome was unclear in eight studies[33, 34, 36, 37, 48, 52–54]. They were measured synchronously in four studies,[39, 41, 43, 45] and measurement of the exposure preceded that of the outcome in nine studies [35, 38, 40, 42, 46, 47, 49–51]. In one study, the exposure measures were from census data collected 1980–1990, the same time period as the outcome [44].

Association of SES and preterm birth

Ten different measures of maternal SES were used, broadly either individual or area-based (Table 3). Six separate individual level measures were used; maternal education was the most frequent (n = 7) [33, 34, 46, 47, 49–51], followed by occupation (each n = 3) [43, 48, 52], two used income [35, 45], two used different composite measures [40, 54], and one used perceived lack of time and money [41]. Four measures were area-based: a composite SES score (n = 4) [36, 38, 39, 53], the proportion of residents in poverty [42], a measure of disadvantage [37], and measures of neighbourhood context (for African-American mothers: median income and proportion of adult male unemployment in 1990; for white women: change in proportion of adult male unemployment 1980–1990) [44].

Eighteen studies found that lower SES was significantly associated with increased preterm birth, using both individual and area-based measures (Table 4). Three found no significant association [36, 42, 54], while one found an association for African-American participants only [44]. Two of the studies finding no significant association measured the effect of neighbourhood SES while controlling for individual measures of SES.

Table 4.

Estimated total effect and standardised mediator effect (proportion eliminated by mediation) from included studies (n = 22)

| Paper | Effect of SES on PTB (95% confidence interval if available) | Mediator | Prevalence of mediator in sample | Proportion eliminated (95% confidence interval if available) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poulsen et al. (2019) [33] Denmark | Total effect RD: 2.0 (1.4, 2.5) excess PTB/100 singleton deliveries | Smoking | 17% total; 39% short education, 8% long | 22% (11%, 31%)a |

| Poulsen et al. (2019) [33] Netherlands | Total effect RD: 3.2 (0.8, 5.2) | 19% total; 41% short education, 7% long | 10% (-22%, 29%) | |

| Poulsen et al. (2019) [33] Norway | Total effect RD: 2.0 (0.9, 3.0) | 9% total; 34% short education, 4% long | 19% (-1%, 29%)a | |

| Ross et al. (2019) [34] | Direct coefficient: 0.072* Total effect coefficient 0.077 | Pre-eclampsia | 5% in black women, 3% in white women | 6.5%a |

| Dolatian et al. (2014) [35] | Direct coefficient: 0.06* Total effect coefficient: 0.06126* | Perceived stress | Mean | 11.8%a |

| Perceived social support through stress | Mean | Mediated effect in opposite directiona | ||

| Combined | 2.1%a | |||

| Clayborne et al. (2017) [36] | Total effect OR: 0.91 (0.64, 1.31) | Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) | Mean | Cannot be estimated |

| Gestational weight gain | Mean | Cannot be estimated | ||

| Combined | Cannot be estimateda | |||

| Dooley (2009) [37] (PhD thesis) | Direct effect: 43.29% increase in odds/standard deviation increase. Total effect**: 46.01%* | Medical risk | 13% | 2.9%a |

| Smoking | 13% | 3.0%a | ||

| Perceived neighbourhood support | Mean | No indirect effect | ||

| Mehra et al. (2019) [38] | Direct effect coefficient: 0.036. Total effect coefficient: 0.059* | Hypertension | 10% | 22.0%a |

| Infection | 28% | 16.9%a | ||

| Meng et al. (2013) [39] | Total effect coefficient: 0.981 (0.626–1.337) | SES-related support | Composite measure | 11.7%a |

| Psychosocial | Composite measure | 2.1%a | ||

| Behavioural | Composite measure | 5.5%a | ||

| Health | Composite measure | 6.4%a | ||

| Mirabzadeh et al. (2013) [40] | Total effect coefficient: 0.1441a | Perceived social support through stress | Mean | 8.1%a |

| Stress, depression, and anxiety | Mean | 22.5%a | ||

| Combined | 30.6%a | |||

| Misra et al. (2001) [41] | Total effect OR: 2.85 (1.85–4.40) | Psychosocial factors only | 26% severe stress | 44% |

| Biomedical and psychosocial factors | 5% chronic disease | 64% | ||

| Nkansah-Amankra et al. (2010) [42] | Total effect OR 1.34 (0.80–2.25) | Maternal stress (emotional, financial, spousal-related, traumatic) | 14% low poverty, 57% high poverty | No significant total effect |

| Räisänen et al. (2013) [43] | Total effect OR: Extremely PTB 1.61 (1.38–1.89); Very PTB 1.48 (1.31–1.68); Moderately PTB 1.27 (1.22–1.32) | Smoking | 12% to 18% by gestational age category | 26% for extremely PTB 33% for very PTB 30% for moderately PTB |

| Other factors and smoking | Composite measure | 39% for extremely PTB 50% for very PTB 41% for moderately PTB | ||

| Ahern et al. (2003) [44] African-American | Total effect parameter estimate proportion unemployed: 44.4* | Cigarettes per day | Mean | 3% |

| Ahern et al. (2003) [44] White | Total effect parameter estimate change in unemployed: -3.32 | No significant total effect | ||

| Amegah et al. (2013) [45] | Total effect RR: 1.83 (1.31–2.56) | Malaria infection during pregnancy | 48% | No effect |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 33% healthy weight | 17% | ||

| Cooking fuel used | 18% LPG, 24% charcoal, 5% firewood | 22% | ||

| Combined | 30% | |||

| van den Berg et al. (2012) [46] | Total effect OR: 1.95 (1.19–3.20) | Smoking | 7% total, 33% in low educated, 2% in high educated | 43% |

| Smoking and environmental tobacco exposure | 6% total, 27% in low educated, 1% in high educated | 39% | ||

| Morgen et al. (2008) [47] | HR primiparous: 1.22 (1.04–1.42) HR multiparous: 1.56 (1.31–1.87) | Smoking | 26% to 35% by gestational age category | 5% in primiparous 23% in multiparous |

| Alcohol | 40% to 45% by gestational age category | 5% in primiparous 4% in multiparous | ||

| Binge drinking | 25% to 26% by gestational age category | 5% in primiparous no effect in multiparous | ||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | Mean | 9% in primiparous 2% in multiparous | ||

| Gestational weight gain | Mean | 5% in primiparous 4% in multiparous | ||

| Combined | 23% in primiparous 30% in multiparous | |||

| Gisselmann and Hemström (2008) [48] | Total effect OR: 1.41* | Job control | Not stated | 44% |

| Job hazards | Not stated | 5% | ||

| Physical demands | Not stated | 22% | ||

| All working conditions | Not stated | 46% | ||

| Niedhammer et al. (2012) [49] | Total effect HR: 2.14 (1.05–4.38) | Rented home | 43% lower than secondary, 15% higher than secondary | 26% |

| Crowded home | 18% lower than secondary, 5% higher than secondary | 13% | ||

| Material factors | Composite | 33% | ||

| Smoking | 46% lower than secondary, 16% higher than secondary | 2% | ||

| Alcohol | 50% lower than secondary, 62% higher than secondary | 14% | ||

| Behavioural | Composite | 10% | ||

| Saturated fatty acids (nutritional factors) | 31% lower than secondary, 20% higher than secondary | 14% | ||

| Material + behavioural | Composite Measure | 38% | ||

| Material + behavioural + nutritional | Composite Measure | 42% | ||

| Jansen et al. (2009) [50] | Total effect OR: 1.89 (1.28–2.80) | Mother’s age | Mean | 22% |

| Mothers’ height | Mean | 22% | ||

| Preeclampsia | 2% total, 1% high, 4% low education | 13% | ||

| Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) | 1% total, 1% high, 2% low education | 12% | ||

| Marital status (single) | 8% total, 3% high, 20% low education | 2% | ||

| Pregnancy planning (unplanned) | 19% total, 10% high, 34% low education | No effect | ||

| Financial concerns | 12% total, 5% high, 30% low education | 19% | ||

| Long-lasting difficulties | Mean | 11% | ||

| Psychopathology | Mean | 16% | ||

| Working hours | Mean | No effect | ||

| Smoking | 18% total, 5% high, 45% low education | 8% | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 50% total, 68% high, 25% low education | 17% | ||

| BMI | 67% total healthy weight, 75% high, 51% low education | 7% | ||

| All except preeclampsia/IUGR/ working hours/pregnancy planning | Composite Measure | 69% | ||

| All except working hours/pregnancy planning | Composite Measure | 89% | ||

| Quispel et al. (2014) [51] | Total effect OR: 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | Depression score | 15% | No effect |

| Gissler et al. (2003) [52] | Total effect OR: 1.35 (1.25–1.45) | Smoking | 15% total, 5% upper white collar, 26% blue collar workers | 42% |

| Gray et al. (2008) [53] | Total effect OR: 1.49 (1.43–1.54) | Smoking | For 2 periods: 30% & 29% total, 15% for both periods in least deprived, 43% & 39% in most deprived | 45% |

| de Oliveira et al. (2019) [54] | Direct standardised estimate: -0.083 | Inadequate prenatal care | Not stated | Cannot be estimateda |

| Unwanted pregnancy | Cannot be estimateda |

* p value < 0.05, ** Percentage change in the odds per standard deviation increase

a indirect effect significant, PTB preterm birth, HR hazard ratio, OR odds ratio, RR relative risk, RD risk difference, coefficient = beta coefficient, LPG liquefied petroleum gas, Mean mean score so prevalence score not calculable

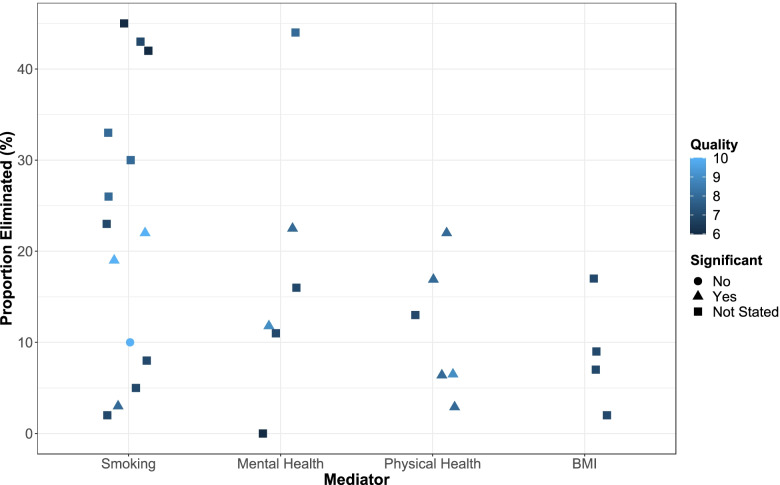

Mediators

The most assessed mediators by the ‘proportion eliminated’ metric were: maternal smoking during pregnancy; mental health; physical health conditions; and BMI (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Harvest plot of proportion eliminated metric for the four most commonly examined mediators. Proportion eliminated: proportion that differences in preterm birth between socioeconomic groups would be reduced by if the mediator was the same for all pregnant women. Colour shows quality score (lighter shade indicates higher score) and shape is significance of indirect effect. Only studies with a significant total effect of SES on preterm birth were included and a study using a continuous measure of smoking was not included. BMI body mass index

Maternal smoking during pregnancy

Ten studies reported the potential mediating effect of smoking, the most frequent mediator studied, with sixteen estimates of proportion eliminated metric. One of these studies used number of cigarettes smoked [44], two categorised number smoked (none, 1–10, more than 10 cigarettes) [33, 47], two included an ex-smoking category [49, 50], one used a mixture of binary variable (yes/no) and the addition of quitters for later in the study period [43], and four used binary variables (smoker/non-smoker) only [37, 46, 52, 53]. Two estimates used cigarettes smoked as a linear variable (thus excluded from Fig. 2 as not comparable to categorised results).

The 16 estimates ranged from 2% eliminated [49] to 45% [53]. Only two studies reported the significance of the indirect effect. Poulsen et al. [33] estimated a significant indirect effect in Denmark and Norway, equating to a significant proportion eliminated of 22% (95% CI 11%, 31%) in Denmark and non-significant proportion eliminated of 19% (-1%, 29%) in Norway. The same study also found a non-significant indirect effect through smoking in the Netherlands, where proportion eliminated was 10% (-22%, 29%), however there was a much smaller sample size. Dooley (2009) [37] found there was a significant indirect effect, equating to 3% eliminated (CIs not provided).

Räisänen et al. [43] reported the largest study (nearly 1.4 million births), finding the proportion eliminated was 26% for extremely preterm births (< 28 weeks gestation), 33% for very preterm births (28–32 weeks gestation), and 30% for moderately preterm births (32–37 weeks).

Ahern et al. [44] found that number of cigarettes smoked eliminated 3% of the SES effect on preterm birth in African American mothers while the SES effect in white mothers was not significant. Niedhammer et al. [49] found the proportion eliminated was 2%, and Jansen et al. [50] found that the proportion eliminated was 8%. These three studies had small sample sizes when compared with the other studies (all less than 4,000 participants). Another smaller study, van den Berg et al., found the proportion eliminated to be 43% [46].

One study of approximately 38,000 primiparous women found the proportion eliminated was 5% [47]. Notably, the same study found the proportion eliminated was 23% in a similar number of multiparous women. Two large, lower quality studies (n = 400,752 and n = 548,913) found proportion eliminated was over 40% [52, 53].

Maternal mental health

Six studies assessed the potential indirect effect of SES on preterm birth via maternal mental health. All studies used verified scales, with two focused on stress, depression, or anxiety measured during pregnancy [35, 40], two focused on stress alone (one measured during and one after) [41, 42], one focused on depression post-delivery [51], and one used both ‘general distress and psychiatric symptoms’ and stress one year pre-pregnancy [50]. Two studies also included assessment of level of social support and reported no direct effect on preterm birth [35, 40], which corresponded with Dooley finding no indirect effect of SES on preterm birth through support [37].

The six estimates of the proportion eliminated of the SES effect through maternal mental health ranged from 0 to 44%. Two studies estimated the significance of the indirect pathway, both finding significant indirect paths. Dolatian et al. [35] found that increased income apparently reduced stress and, maybe counterintuitively, perceived social support; increased stress was associated with reduced gestational age, while perceived social support increased gestational age by reducing stress. The proportion eliminated was 12% for stress alone, which reduced to 2% when support was also included. Notably, there was a discrepancy between the graphical results in the path model and the tabulated effects. Mirabzadeh et al. [40] found that the proportion eliminated for stress, depression, and anxiety was 22% and, when combined with level of social support, 31%.

None of the other studies estimated the significance of the indirect effect. Misra et al. [41] found that the proportion eliminated was 44% in black mothers. Nkansah-Amankra et al. [42] found the effect of SES on preterm birth was not significant prior to adjustment, therefore proportion eliminated is not an appropriate metric. Jansen et al. [50] found the proportion eliminated for psychopathology (measured using the Brief Symptom Inventory) was 16%, and for long-lasting difficulties (measured using questionnaire and interview in the year before pregnancy) was 11%. Quispel et al. [51] found there was no proportion eliminated. Mehra et al. [38] found there were no significant indirect effects through mental health conditions so was not reported.

Maternal physical health

Six studies examined the potential mediation of the effect of SES on preterm birth through maternal physical health. Two studies examined pre-eclampsia [34, 50], three used composite measures to determine health (any health condition or one of a selection) [37, 39, 41], and one used specific medical conditions (hypertension and infection) [38]. The proportion eliminated ranged from 3 to 22% for physical health (Fig. 2, however this excludes the results for one of the composite measures).

Of the two studies that examined pre-eclampsia, one found a significant indirect effect while the other did not. Ross et al. [34] found that the proportion eliminated was 6%. Notably, when the analysis was stratified for race, the effect of education on pre-eclampsia was less in black mothers and the indirect effect was smaller and no longer statistically significant. Jansen et al. [50] found that the proportion eliminated was 13% for pre-eclampsia.

Of the four studies that examined pre-existing health, three found significant indirect effects. Dooley (2009) [37] found that the proportion eliminated was 3% (maternal health conditions recorded on the birth certificate). Mehra et al. [38] found the proportion eliminated for hypertension was 22% and for infection was 17%. They found no significant indirect effects through diabetes mellitus so this was not reported. Meng et al. [39] found the proportion eliminated for an unspecified composite of maternal health challenges was 6%. Misra et al. [41] found that the addition of biomedical factors (chronic disease, vaginal bleeding, and no prenatal care) to psychosocial stress increased the proportion eliminated from 44 to 64%.

BMI and gestational weight gain

Four studies measured mediation through pre-pregnancy BMI, with two also examining gestational weight gain. Only one study estimated whether the indirect effect was statistically significant. Clayborne et al. [36] found there was a significant indirect effect through BMI and gestational weight gain together but not separately. The proportion eliminated could not be calculated from the data provided.

The other three studies did not estimate statistical significance of the proportion eliminated or indirect effect. Amegah et al. [45] found that the proportion eliminated for BMI was 17%. Morgen et al. [47] found that the proportion eliminated for BMI was 9% and 2%, and for gestational weight gain was 5% and 4%, in primiparous and multiparous women, respectively. Jansen et al. [50] found the proportion eliminated was 7%.

Maternal alcohol consumption in pregnancy

Three studies considered the mediating effect of categories of maternal alcohol consumption. Morgen et al. [47] found that for alcohol the proportion eliminated was 5% and 4% in primiparous and multiparous women, respectively. For binge drinking the proportion eliminated was 5% in primiparous women with no effect in multiparous women.

Niedhammer et al. [49] found the proportion eliminated was 14%. Jansen et al. [50] found the proportion eliminated 17%. None of the studies estimated statistical significance of the indirect effect. Notably, the two studies that reported prevalence of alcohol consumption by SES groups showed that consumption was more prevalent in higher than lower SES groups.

Working and environmental conditions

Two studies examined environmental conditions. Amegah et al. [45] found the proportion eliminated for cooking fuel (as a measure of indoor air pollution) was 22%. van den Berg et al. [46] found the proportion eliminated for environmental tobacco exposure combined with cigarette-smoking was 39%, however the proportion eliminated was lower than for smoking alone (43%). Living conditions were examined, finding that the proportion eliminated for rented accommodation was 26% and for crowded housing was 13% [49].

Two studies examined working conditions. Gisselmann and Hemström (2008) [48] applied an aggregated measure of working exposure based on occupation, measured up to five years pre-birth. Proportion eliminated was: 46% for working conditions, 44% for job control, 22% for physical demands, and 5% for job hazards. These estimates were larger when analysis was limited to extremely preterm births. Jansen et al. [50] found working hours (measured in late pregnancy) had no indirect effect.

Healthcare (antenatal care and family planning)

de OIliveira et al. found there were significant indirect effects through inadequate prenatal care and unwanted pregnancy [54]. Jansen et al. found no proportion eliminated for unplanned pregnancy [50].

Composite measures

Meng et al. [39] assessed the proportion eliminated by three composite measures, estimating them as: 12% for SES-related support (maternal drug and alcohol abuse, single parent, financial difficulty, no prenatal care, no social support, maternal mental illness); 2% for psychosocial support (single parent, marital distress, family violence, smoking); and 6% for behaviour (infection, drug and alcohol abuse, single parent, financial difficulty, no prenatal care, family violence, smoking).

Misra et al. [41] found the proportion eliminated for health and stress was 64%. Räisänen et al. [43] found the proportion eliminated for smoking and other factors (placental abruption, placenta praevia, major congenital anomaly, anaemia, stillbirth, small for gestational age, and sex of infant) was 39% for extremely preterm births, 50% for very preterm births, and 41% for moderately preterm births.

Amegah et al. [45] found the proportion eliminated for malaria infection, pre-pregnancy BMI, and cooking fuel use combined was 30%. Morgen et al. [47] found the proportion eliminated for a combination of maternal behavioural mediators was 23% and 30% in primiparous and multiparous women, respectively. Niedhammer et al. [49] found the proportion eliminated for combined material, behavioural, and nutritional mediators was 42%. Jansen et al. [50] found the proportion eliminated for combined health, behavioural, and working patterns was 89% (Table 4).

Three studies found that inclusion of these composites removed statistical significance for the SES measures, which suggests complete mediation might be possible [41, 49, 50].

Adjustment for confounders

Studies did not explicitly attribute confounders to the exposure-mediator, the mediator-outcome, or the exposure-outcome paths. The included studies considered various covariates for adjustment. Over three-quarters of the studies adjusted for maternal age as a confounder, and one study treated maternal age as a mediator. Parity was the next most frequently included covariate, included in over one-half of studies. Other notable covariates included ethnicity or race (both categorisations being used in different studies but referring to ethnic group), other measures of SES, and sex of the infant. Maternal health behaviours, health, stress, and prenatal care were all included in some studies as confounders, despite being examined as mediators in other studies. Multiple births and immigration status were more frequently used as exclusion criteria rather than confounders.

Summary of mediation findings

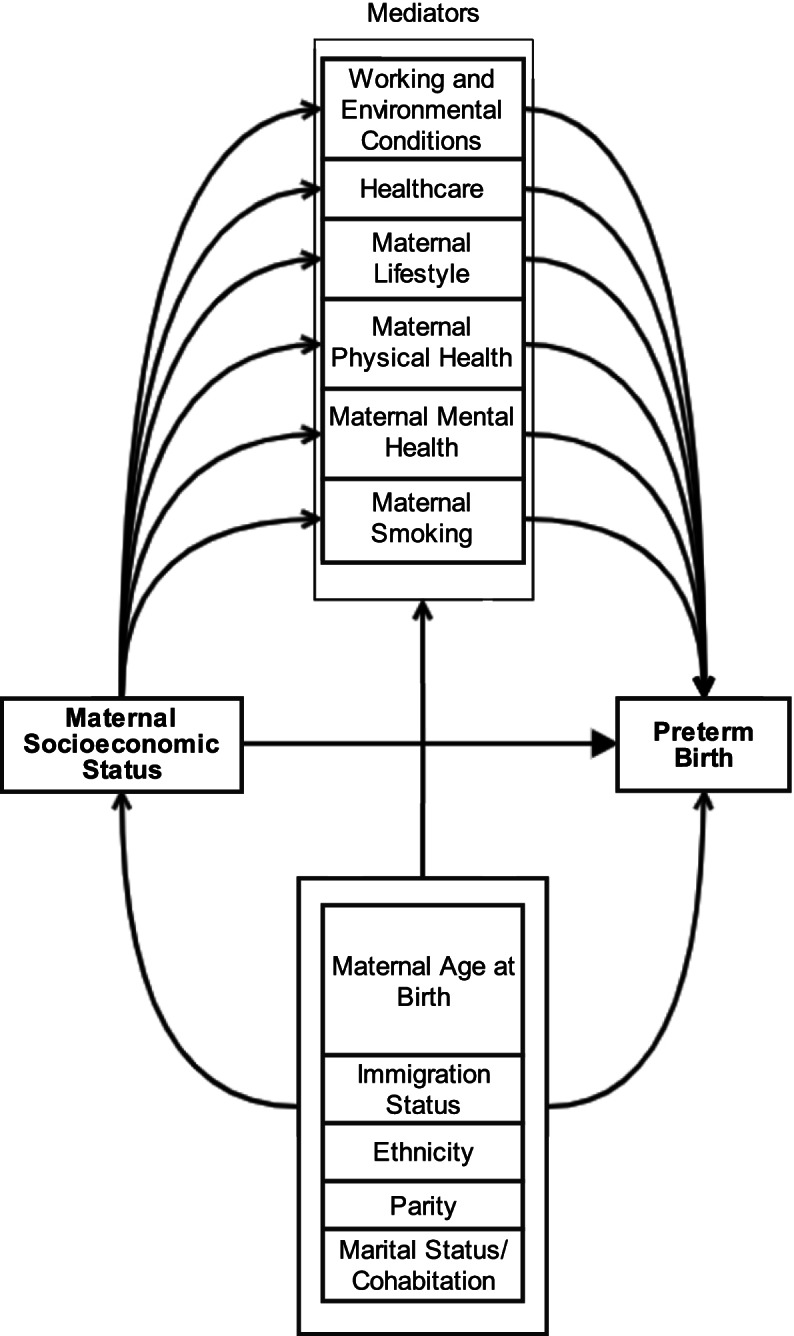

The included studies analysed six groups of mediators (Fig. 3): maternal smoking; maternal mental health; maternal physical health (including BMI); maternal lifestyle (including alcohol consumption); healthcare; and working and environmental conditions.

Fig. 3.

Causal pathway based on results of the studies included in the systematic review

Mediation through smoking was consistently demonstrated. Most studies did not calculate the CI of this, so it is not possible to assess precision. The studies that found small or non-significant effects tended to have smaller sample sizes while larger and higher quality studies found larger and statistically significant effects. There is high confidence of smoking being a mediator, however the size could not be estimated from this evidence.

There was mixed evidence that maternal mental health mediated the SES effect on preterm birth. The studies that found a significant indirect effect had the smallest sample sizes and highest quality, while the largest sample found no significant association between SES and preterm birth. The lowest quality study found no mediating effect. There is moderate confidence of maternal mental health being a mediator.

There is consistent evidence that there is significant mediation through maternal physical health, however the size of this effect depended on the way health was measured. Some specific conditions did not have a significant indirect effect. There is evidence of a significant indirect effect through pre-eclampsia, although this may differ by ethnicity. The evidence consistently shows that SES may have a small indirect effect through BMI, and one study found a significant indirect effect through BMI and gestational weight gain together. There is high confidence of maternal physical health being a mediator.

The evidence consistently shows that SES may have a small indirect effect through alcohol consumption. Despite the consistency, the lack of CI and the small effects mean there is low to moderate confidence that alcohol is a mediator. There is inconsistent evidence for working and environmental conditions, with no estimates of CI and only low-quality evidence for healthcare.

Confounders frequently used were maternal age, ethnicity or race, immigration status, parity, and marital status. It is important to note that the resulting path model (Fig. 3) is based on the evidence in this review and does not represent all variables and relationships that exist on this path or potential confounders.

Discussion

Principal findings

In aiming to identify evidence for mediation of the relationship between SES and preterm birth and to evaluate the quality of the methods used to assess mediation, this review finds that the current evidence is unable to answer our research question definitively. Mediation ranged from none to complete (the SES effect became non-significant), with no variable consistently mediating the effect of SES on preterm birth to the same extent across all studies.

Smoking was the most frequently examined mediator, with high confidence that smoking was a mediator of the effect of SES on preterm birth. There was also high confidence that maternal physical health was a mediator, however there was a wide range of measures of health, for example individual conditions and composite measures. There was lower confidence of mediation for the other identified variables being mediators. Most studies did not calculate the CI of the mediated effect; therefore, it is not possible to state confidently the size of this effect. The studies that found small or non-significant effects tended to have smaller sample sizes while larger and higher quality studies found larger and statistically significant effects.

Most included studies found a significant association between measures of SES and preterm birth prevalence, however the size of this effect ranged widely (from 6 to 185% increase in risk for low SES). Of the studies that found no significant effect of SES on preterm birth, two measured the effect of area-based SES while controlling for individual SES, risking overadjustment if area-based SES is taken as a proxy for individual SES. Two other studies measured the effect of area-based SES while controlling for individual SES, finding the effect significant.

Problems with the mediation methods affect our ability to make causal inferences. Most studies did not discuss the causal assumptions underpinning mediation. This is a particular issue for ‘cross-world independence’; a number of the mediators have inter-relationships, for example maternal health and health behaviours have an effect on obstetric complications [56, 57].

Relevance to other studies

The effect of SES on birth outcomes has been well described, with a recent systematic review and meta-analysis showing significant associations between the wider social determinants of health and negative outcomes, including preterm birth [58]. Other studies, however, have shown a complicated relationship between mediators. Adhikari et al. demonstrated modification of the effect of depression and anxiety on preterm birth by SES [59]. McCall et al. found that, when stratified by smoking status, inequalities in preterm birth were only seen in non-smokers [60]. Studies have found mediation of inequalities in other perinatal outcomes (low birthweight, small for gestational age) [61, 62]. This adds support to the hypothesis that socioeconomic inequalities in preterm birth are at least partly explained by other exposures, however this relationship is potentially complicated by effect modification, highlighting the importance of incorporating exposure-mediator interaction into mediation analysis.

Strengths of the study

The extensive searches of multiple databases, with supplementary searches, allow us to have high confidence that we have selected appropriate studies. Additionally, our quality appraisal included both biases associated with study design and quality of mediation approach. We included all study designs and measures of SES to maximise the evidence available to us for the review.

Limitations of the review

Our inclusion criteria meant there are two major limitations. First, different measures of SES are potentially not comparable. The measure of SES used will affect the extent of inequalities observed in preterm birth [63, 64], particularly when considering area-based and individual measures [65, 66]. There is evidence that disagreement can occur between these measures [67], suggesting that the pathways to inequalities may differ. Notably though, our study showed no clear differences based on measure of SES used, therefore we are considering the different measures as broadly comparable exposures.

Second, only eight studies made clear that the exposure was measured before the outcome, yet temporality is a requirement for causal interpretation. Nevertheless, SES could be argued to be a relatively static exposure in the perinatal period (depending on measurement) so the importance of this potential problem is debatable.

Finally, our search strategy focused on studies that explicitly examined mediation or explanation of inequalities in preterm birth. This could potentially lead to missing studies in which a mediated effect could still be extracted. If the aim of the study was not to assess mediation, however, the causal relationships and pathways would not have been considered. Such an estimation would not have considered confounding, leading to flawed estimates. Minor deviations from the PROSPERO protocol were noted, however these have not impacted on our findings or introduced a new risk of bias.

Limitations of the data

Of limitations in the evidence, first, some potential mediators were not examined. For example, air pollution [68–70], urbanicity [71], and domestic violence [72] have been shown to affect preterm birth risk and are socially patterned and thus are plausible mediators of preterm birth inequalities. Particularly relevant is that the focus of included mediators tends to be individual (behaviours, health status) rather than more upstream and systems-based variables such as access to healthcare and other determinants. Second, assessing the measurement of the included mediators was problematic. For example, some mediators were not measured during pregnancy and were aggregated [48], and some composites combined seemingly unconnected mediators [39, 43].

Third, most studies treated preterm birth as a homogenous group, however extremely preterm birth and late preterm birth differ in both consequences and causes [73]. Most studies did not report whether the preterm birth was iatrogenic or spontaneous, which affects risks of adverse consequences, however the link with SES is unclear [74, 75]. Fourth, most of the included studies did not estimate CI for the proportion eliminated and 11 studies did not estimate mediator significance (all used the difference method) [76], limiting our synthesis. This means that studies including the same mediators do not necessarily show different results but differences found may be due to uncertainty in the effect that we were unable to quantify. Finally, not assessing the exposure-mediator interaction can significantly and substantially bias results.

Conclusions

Effective intervention to reduce inequalities in preterm birth may involve action on mediators of the effect of maternal SES on preterm birth. Complete mediation of the SES effect on preterm birth is unlikely by individual variables, given that most studies show a large residual direct effect of SES. This suggests that a focus on modifiable socioeconomic determinants, such as reducing poverty and educational inequality, is necessary to address inequalities in preterm birth, alongside action on mediating pathways.

Given the variable quality of the evidence, from the study design and particularly the mediation methods used, there is a pressing need for more robust primary research into mediation to identify causal evidence to inform policy. The evidence does suggest that risk factors lying on the pathway from SES to preterm birth explain some of the inequalities in preterm birth. Action on smoking is most strongly supported, for example through financial incentives [77]. Overall though, the current evidence precludes ranking these risks to maximise outcomes from policy action.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Deviations from PROSPERO protocol

Additional file 5: Table showing quality appraisal score for each study; Conf. Confounding, Int. Interaction, Assump. Assumptions

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- DAG

Directed acyclic graph

- SES

Socioeconomic status

Authors’ contributions

PM was involved in conception, design, screening, extraction, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. GM was involved in screening, extraction, analysis, and revision of the manuscript. AP was involved in screening, analysis, and revision of the manuscript. DS was involved in design, analysis, and revision of the manuscript. BB was involved in design, analysis, and revision of the manuscript. SP was involved in design, analysis, and revision of the manuscript. DTR was involved in design, analysis, and revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. “The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.”

Funding

PM is funded through an MRC Clinical Research Training Fellowship (MR/T00794X/1). DTR is funded by the MRC on a Clinician Scientist Fellowship (MR/P008577/1). BB is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast (ARC NWC). BB and DTR are supported by the NIHR School for Public Health Research. The funders played no role in design, analysis, and interpretation of the study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e37–46. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(3):263–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Ruiz M, Goldblatt P, Morrison J, Kukla L, Švancara J, Riitta-Järvelin M, et al. Mother’s education and the risk of preterm and small for gestational age birth: a DRIVERS meta-analysis of 12 European cohorts. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(9):826. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-205387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson K, Moffat M, Arisa O, Jesurasa A, Richmond C, Odeniyi A, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities and adverse pregnancy outcomes in the UK and Republic of Ireland: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e042753. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jardine J, Walker K, Gurol-Urganci I, Webster K, Muller P, Hawdon J, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes attributable to socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in England: a national cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10314):1905–1912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01595-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moster D, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):262–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Straatmann VS, Lai E, Lange T, Campbell MC, Wickham S, Andersen AMN, et al. How do early-life factors explain social inequalities in adolescent mental health? Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019;73(11):1049. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-212367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creese H, Lai E, Mason K, Schlüter DK, Saglani S, Taylor-Robinson D, et al. Disadvantage in early-life and persistent asthma in adolescents: a UK cohort study. Thorax. 2021 Oct 12;thoraxjnl-2021–217312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kramer MS, Goulet L, Lydon J, Séguin L, McNamara H, Dassa C, et al. Socio-economic disparities in preterm birth: causal pathways and mechanisms. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(s2):104–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arora CP, Kacerovsky M, Zinner B, Ertl T, Ceausu I, Rusnak I, et al. Disparities and relative risk ratio of preterm birth in six Central and Eastern European centers. Croat Med J. 2015;56(2):119–127. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2015.56.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouthoorn SH, Silva LM, Murray SE, Steegers EAP, Jaddoe VWV, Moll H, et al. Low-educated women have an increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: the Generation R Study. Acta Diabetol. 2015;52(3):445–452. doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0668-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien EC, Alberdi G, McAuliffe FM. The influence of socioeconomic status on gestational weight gain: a systematic review. J Public Health. 2018;40(1):41–55. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdx038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delnord M, Blondel B, Zeitlin J. What contributes to disparities in the preterm birth rate in European countries? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27(2):133–142. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanderweele T. Explanation in Causal Inference: Methods for Mediation and Interaction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whibley D, AlKandari N, Kristensen K, Barnish M, Rzewuska M, Druce KL, et al. Sleep and pain: a systematic review of studies of mediation. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(6):544–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Ncube CN, Enquobahrie DA, Albert SM, Herrick AL, Burke JG. Association of neighborhood context with offspring risk of preterm birth and low birthweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:156–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Banay RF, Bezold CP, James P, Hart JE, Laden F. Residential greenness: current perspectives on its impact on maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:133–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Culhane JF, Elo IT. Neighborhood context and reproductive health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):S22–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heo S, Fong KC, Bell ML. Risk of particulate matter on birth outcomes in relation to maternal socio-economic factors: a systematic review. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14(12):123004. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab4cd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro GD, Fraser WD, Frasch MG, Séguin JR. Psychosocial stress in pregnancy and preterm birth: associations and mechanisms. J Perinat Med. 2013;41(6):631–645. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2012-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abu-Saad K, Fraser D. Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32(1):5–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Metcalfe A, Lail P, Ghali WA, Sauve RS. The association between neighbourhoods and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of multi-level studies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25(3):236–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hetherington E, Doktorchik C, Premji SS, McDonald SW, Tough SC, Sauve RS. Preterm birth and social support during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29(6):523–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Reviewer 4: software for research synthesis, EPPI-Centre Software. London: Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.VanderWeele TJ. Policy-relevant proportions for direct effects. Epidemiol. 2013;24(1):175–176. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182781410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronzi S, Orton L, Pope D, Valtorta NK, Bruce NG. What is the impact on health and wellbeing of interventions that foster respect and social inclusion in community-residing older adults? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Cashin AG, McAuley JH, Lamb S, Hopewell S, Kamper SJ, Williams CM, et al. Items for consideration in a reporting guideline for mediation analyses: a Delphi study. BMJ EBM. 2021;26(3):106. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferguson KD, McCann M, Katikireddi SV, Thomson H, Green MJ, Smith DJ, et al. Evidence synthesis for constructing directed acyclic graphs (ESC-DAGs): a novel and systematic method for building directed acyclic graphs. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(1):322–329. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews – A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Version 1. Lancaster: Lancaster University; 2006.

- 31.Pennington A, Orton L, Nayak S, Ring A, Petticrew M, Sowden A, et al. The health impacts of women’s low control in their living environment: a theory-based systematic review of observational studies in societies with profound gender discrimination. Health Place. 2018;51:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Ogilvie D, Fayter D, Petticrew M, Sowden A, Thomas S, Whitehead M, et al. The harvest plot: a method for synthesising evidence about the differential effects of interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Poulsen G, Andersen AMN, Jaddoe VWV, Magnus P, Raat H, Stoltenberg C, et al. Does smoking during pregnancy mediate educational disparities in preterm delivery? Findings from three large birth cohorts. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(2):164–171. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross KM, Dunkel Schetter C, McLemore MR, Chambers BD, Paynter RA, Baer R, et al. Socioeconomic status, preeclampsia risk and gestational length in black and white women. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(6):1182–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Dolatian M, Mirabzadeh A, Forouzan AS, Sajjadi H, Alavimajd H, Mahmoodi Z, et al. Relationship between structural and intermediary determinants of health and preterm delivery. J Reprod Infertil. 2014;15(2):78–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Clayborne ZM, Giesbrecht GF, Bell RC, Tomfohr-Madsen LM. Relations between neighbourhood socioeconomic status and birth outcomes are mediated by maternal weight. Soc Sci Med. 2017;175:143–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Dooley P. Examining individual and neighborhood-level risk factors for delivering a preterm infant. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis. Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati; 2009:189.

- 38.Mehra R, Shebl FM, Cunningham SD, Magriples U, Barrette E, Herrera C, et al. Area-level deprivation and preterm birth: results from a national, commercially-insured population. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):236. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6533-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng G, Thompson ME, Hall GB. Pathways of neighbourhood-level socio-economic determinants of adverse birth outcomes. Int J Health Geogr. 2013;12(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mirabzadeh A, Dolatian M, Forouzan AS, Sajjadi H, Majd HA, Mahmoodi Z. Path analysis associations between perceived social support, stressful life events and other psychosocial risk factors during pregnancy and preterm delivery. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(6):507–14. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.11271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misra DP, O’Campo P, Strobino D. Testing a sociomedical model for preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(2):110–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nkansah-Amankra S, Luchok KJ, Hussey JR, Watkins K, Liu X. Effects of maternal stress on low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes across neighborhoods of South Carolina, 2000–2003. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(2):215–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Räisänen S, Gissler M, Saari J, Kramer M, Heinonen S. Contribution of risk factors to extremely, very and moderately preterm births – Register-based analysis of 1,390,742 singleton births. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e60660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Ahern J, Pickett KE, Selvin S, Abrams B. Preterm birth among African American and white women: a multilevel analysis of socioeconomic characteristics and cigarette smoking. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(8):606–611. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.8.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amegah AK, Damptey OK, Sarpong GA, Duah E, Vervoorn DJ, Jaakkola JJK. Malaria infection, poor nutrition and indoor air pollution mediate socioeconomic differences in adverse pregnancy outcomes in Cape Coast, Ghana. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.van den Berg G, van Eijsden M, Vrijkotte TGM, Gemke RJBJ. Educational inequalities in perinatal outcomes: the mediating effect of smoking and environmental tobacco exposure. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Morgen CS, Bjørk C, Andersen PK, Mortensen LH, Nybo Andersen AM. Socioeconomic position and the risk of preterm birth—a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):1109–1120. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gisselmann MD, Hemström Ö. The contribution of maternal working conditions to socio-economic inequalities in birth outcome. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1297–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niedhammer I, Murrin C, O’Mahony D, Daly S, Morrison JJ, Kelleher CC, et al. Explanations for social inequalities in preterm delivery in the prospective Lifeways cohort in the Republic of Ireland. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(4):533–538. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jansen PW, Tiemeier H, Jaddoe VWV, Hofman A, Steegers EAP, Verhulst FC, et al. Explaining educational inequalities in preterm birth: the Generation R study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94(1):F28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Quispel C, Bangma M, Kazemier BM, Steegers EAP, Hoogendijk WJG, Papatsonis DNM, et al. The role of depressive symptoms in the pathway of demographic and psychosocial risks to preterm birth and small for gestational age. Midwifery. 2014;30(8):919–925. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gissler M, Meriläinen J, Vuori E, Hemminki E. Register based monitoring shows decreasing socioeconomic differences in Finnish perinatal health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(6):433. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gray R, Bonellie S, Chalmers J, Greer I, Jarvis S, Williams C. Social inequalities in preterm birth in Scotland 1980–2003: findings from an area-based measure of deprivation. BJOG. 2008;115(1):82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Oliveira AA, de Almeida MF, da Silva ZP, de Assunção PL, Silva AMR, dos Santos HG, et al. Fatores associados ao nascimento pré-termo: da regressão logística à modelagem com equações estruturais. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2019;35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Kane JB, Miles G, Yourkavitch J, King K. Neighborhood context and birth outcomes: going beyond neighborhood disadvantage, incorporating affluence. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:699–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Scime NV, Chaput KH, Faris PD, Quan H, Tough SC, Metcalfe A. Pregnancy complications and risk of preterm birth according to maternal age: a population-based study of delivery hospitalizations in Alberta. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(4):459–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Salihu HM, Mbah AK, Alio AP, Clayton HB, Lynch O. Low pre-pregnancy body mass index and risk of medically indicated versus spontaneous preterm singleton birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144(2):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amjad S, MacDonald I, Chambers T, Osornio-Vargas A, Chandra S, Voaklander D, et al. Social determinants of health and adverse maternal and birth outcomes in adolescent pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(1):88–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Adhikari K, Patten SB, Williamson T, Patel AB, Premji S, Tough S, et al. Neighbourhood socioeconomic status modifies the association between anxiety and depression during pregnancy and preterm birth: a Community-based Canadian cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e031035. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCall SJ, Green DR, Macfarlane GJ, Bhattacharya S. Spontaneous very preterm birth in relation to social class, and smoking: a temporal-spatial analysis of routinely collected data in Aberdeen, Scotland (1985–2010) J Public Health. 2020;42(3):534–541. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdz042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reime B, Ratner PA, Tomaselli-Reime SN, Kelly A, Schuecking BA, Wenzlaff P. The role of mediating factors in the association between social deprivation and low birth weight in Germany. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1731–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakamura A, Pryor L, Ballon M, Lioret S, Heude B, Charles MA, et al. Maternal education and offspring birth weight for gestational age: the mediating effect of smoking during pregnancy. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(5):1001–1006. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Snelgrove JW, Murphy KE. Preterm birth and social inequality: assessing the effects of material and psychosocial disadvantage in a UK birth cohort. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(7):766–775. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luo ZC, Wilkins R, Kramer MS, Fetal and Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Effect of neighbourhood income and maternal education on birth outcomes: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2006;174(10):1415–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Subramanian SV, Chen JT, Rehkopf DH, Waterman PD, Krieger N. Comparing individual- and area-based socioeconomic measures for the surveillance of health disparities: a multilevel analysis of Massachusetts births, 1989–1991. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(9):823–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Moss JL, Johnson NJ, Yu M, Altekruse SF, Cronin KA. Comparisons of individual- and area-level socioeconomic status as proxies for individual-level measures: evidence from the Mortality Disparities in American Communities study. Popul Health Metr. 2021;19(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12963-020-00244-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pardo-Crespo MR, Narla NP, Williams AR, Beebe TJ, Sloan J, Yawn BP, et al. Comparison of individual-level versus area-level socioeconomic measures in assessing health outcomes of children in Olmsted County Minnesota. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(4):305–10. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Asta F, Michelozzi P, Cesaroni G, De Sario M, Badaloni C, Davoli M, et al. The modifying role of socioeconomic position and greenness on the short-term effect of heat and air pollution on preterm births in Rome, 2001–2013. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Padula AM, Mortimer KM, Tager IB, Hammond SK, Lurmann FW, Yang W, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and risk of preterm birth in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(12):888–95e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bekkar B, Pacheco S, Basu R, DeNicola N. Association of air pollution and heat exposure with preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirth in the US: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e208243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Auger N, Authier MA, Martinez J, Daniel M. The association between rural-urban continuum, maternal education and adverse birth outcomes in Québec. Canada J Rural Health. 2009;25(4):342–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Donovan B, Spracklen C, Schweizer M, Ryckman K, Saftlas A. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and the risk for adverse infant outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2016;123(8):1289–1299. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Auger N, Abrahamowicz M, Wynant W, Lo E. Gestational age-dependent risk factors for preterm birth: associations with maternal education and age early in gestation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;176:132–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Joseph KS, Fahey J, Shankardass K, Allen VM, O’Campo P, Dodds L, et al. Effects of socioeconomic position and clinical risk factors on spontaneous and iatrogenic preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:117:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Henderson JJ, McWilliam OA, Newnham JP, Pennell CE. Preterm birth aetiology 2004–2008. Maternal factors associated with three phenotypes: spontaneous preterm labour, preterm pre-labour rupture of membranes and medically indicated preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(6):642–7. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.597899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Berlin I, Berlin N, Malecot M, Breton M, Jusot F, Goldzahl L. Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021;375:e065217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 2: Deviations from PROSPERO protocol

Additional file 5: Table showing quality appraisal score for each study; Conf. Confounding, Int. Interaction, Assump. Assumptions

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.