Abstract

Given the public resentment that trailed the unprecedented lockdown order enforced as a public health emergency control strategy to contain the spread of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, this study explored citizens' compliance with the order and how its enforcement occasioned illegal police practices in Nigeria. With a qualitative approach, this study recruited 90 participants using varieties of sampling methods to understand public behaviour and police conduct in the enforcement of the order. From the insights gathered with a semi-structured interview and analysed with the thematic analysis method, the study observed that economic hardship, unavoidable matters from the citizens’ end and mistrust of authorities fueled non-compliance. Such mistrust amplified misinformation during the pandemic. Although there was a reasonable level of compliance, the pre-existing police illegalities (extortion and bribery) facilitated the cases of non-compliance in Nigeria. Also, hostility ensued between police personnel and citizens during the enforcement of the lockdown. Therefore, this study advised the government and stakeholders on the imperatives of adequate socio-economic preparations, emphasising public trust and the provision of relief materials. Additionally, it suggested to the police authorities reform ideas to better equip, monitor, and manage police resources for effective handling of future pandemics.

Keywords: Enforcement, Compliance, COVID-19, Lockdown, Nigeria, Police illegalities

1. Introduction

Enforcement of lockdown and other related measures meant to contain COVID-19 pandemic is handled by the police (White and Fradella, 2020) [1], a public agency that provides a peaceful and secure environment for citizens to live and contribute toward socio-economic, political and development of a country. In times of emergency, the police act and adjust their operational structures and systems to meet the current reality. In addition to the police's existent responsibilities, these arrangements are required to sustain order and continue local policing activities while experiencing resource burdening (Stogner et al., 2020) [2]. Hence, its officers are vulnerable to disease, which has posed severe threats to the global community, thus, necessitating restrictive measures. Due to its global devastation, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared it a pandemic on March 11, 2020.

Accordingly, as part of the global measures to mitigate its continued spread, Nigeria, like most affected countries, introduced a nationwide lockdown enforced by its police and legitimised with the enactment of the COVID-19 Regulation Act, 2020, following the outbreak of the pandemic in the country on February 27, 2020. A month later, the recorded cases had increased to 81 in ten states, with Lagos having 52.64% of the cases (Amzat et al., 2020) [3]. In implementing the lockdown, the Nigerian Police Force (NPF) issued guidelines to its officers on protective measures, engagement with citizens and the disease victims, prevention of misinformation and rumour, medical emergencies and management of public order (Nigeria Police Force, 2020) [4]. Foundational to the guidelines, the COVID-19 Regulation stipulated the government's first-aid efforts concerning the stay-at-home order: restriction of movement in Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Ogun and Lagos State, continued operation of Lagos seaports, suspension of passenger aircraft, provision of relief materials, among others. Public places, private business establishments, schools and government officers were shut down and restrictions on movement. People were encouraged to work from their homes and discouraged from going out and attending crowded places. During the lockdown period, which spanned from March 30 to April 28, 2020, the number of confirmed cases rose from 131 with two deaths to 1300 with 40 deaths.

Despite the directives and regulations, there were cases of violation of the stay-at-home orders as insinuated in the media (Guardian, 2021) [5]. The restrictive approach to curb the pandemic did not reflect the country's internal socio-economic and political peculiarities and unique environmental factors before adopting the Western approach (Chidume et al., 2020) [6], Iwuoha and Aniche (2020) [7] termed ‘copy and paste’ from developed countries where 18% of the population are in the informal sectors. Those in such sectors constituting 90% of the Nigerian economy have no social security (Trading Economics, 2020) [8]. As a result, compliance with the government orders became distant. In addition to the non-compliant tendency, there were armed robbery and burglary incidents in Lagos and neighbouring Ogun State (Iwuoha and Aniche, 2020) [7]. Coupled with an insufficient level of investment in the healthcare system, the dwindling economy caused by a decrease in oil revenue and a decline in crude oil export that fell below USD 20 a barrel in mid-April 2020 (Onyekwena and Ekeruche, 2020) [9] denied the government financial capacity to provide necessary public goods and assuage the attendant pains of the citizens. Thus, fueling initial public affectivity that COVID-19 was a disease meant for the elite, who returned from overseas or had contact with the political ruling class as three state governors and some political appointees contracted the disease (Amzat et al., 2020) [3].

As legitimacy is the specific worth or respect that citizens ascribe to leadership things they perceive as deserving of their support (Peter, 2010) [10], the Nigerian State couldn't achieve total compliance due to the disconnect between the government and citizens. Political office holders' image is not complimentary and successive political administrations have failed to provide public good to the entire citizenry, thus undermining the state's legitimacy and weakening its police's ability to enforce compliance (Akinlabi, 2020) [11]. How the police enforce laws and respect democratic standards forms police legitimacy and demonstrate the state's commitment to those standards. Many Nigerian police officers, however, engage in unethical practices in their daily conduct with the citizens while on duty (Aremu et al., 2009) [12]. Upon seeing police officers from a close distance, it is common to see them being addressed with remarks such as Askari (corrupt), Egunje (bribe), and Roja me (grease my palm), which paint them as infamously corrupt state agents that are unanswerable to the public they are maintained to serve (Akinlabi, 2011) [13]. Hence, the Nigerian public assessment and opinion of the police that influence police legitimacy is poor, thereby creating a serious impediment to law enforcement. However, these officers were deployed nationwide to enforce the stay-at-home order. While the restriction on movement remains a crucial element in reducing community transmission of the pandemic, police unethical practices characterised its enforcement, which resulted from existing challenges ravaging the police. Thus, such characterisation strained the cordial police-community relation needed for law enforcement and public order during a pandemic. The officers lack sufficient training, sound welfare condition and other necessities, which make effective service delivery to the public difficult (Esomchi, 2017) [14]. They are involved in the use of excessive force and torture on citizens (Babatunde, 2017) [15], which violate human rights (Adongoi and Abraham, 2017) [16]. These problems were alluded to have prevailed in the enforcement of the curfew directives. Therefore, the need to investigate the interaction of these issues with public behaviour in the context of the unprecedented lockdown in Ilorin, Nigeria.

1.1. Nigeria's Preparedness against COVID-19 pandemic

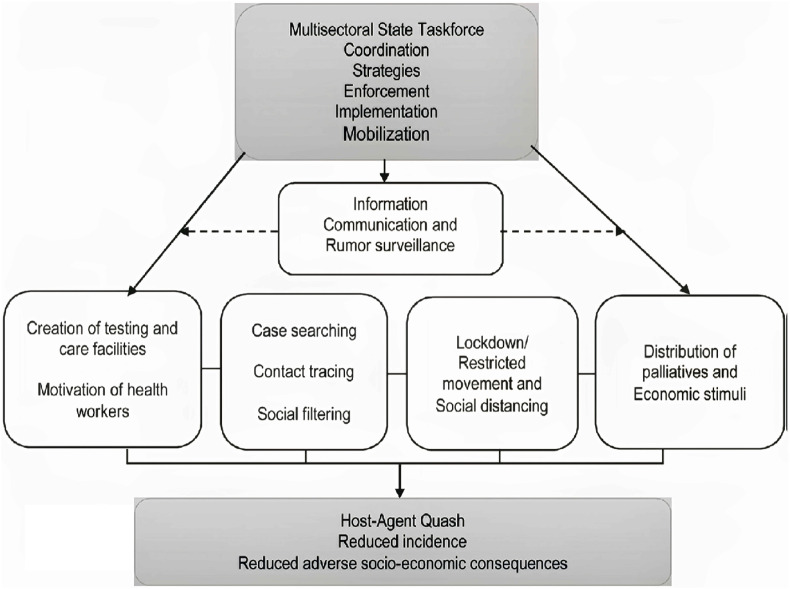

As a result of the rapid and large-scale contagion of COVID-19 occasioned by global transit of people and commercial activities, the Nigerian authorities observed the need to prepare fully against possible outbreak and spread. Thus, the government took some actions; public health safety guidelines, public enlightenment, monetary initiatives for businesses and control of large sectors of the economy (see Fig. 1 ). In addition, social interventions for the vulnerable population and the provision of 500 billion Naira crisis intervention funds to states authorities for response efforts. On March 9, 2020, the government established a task force branded as the COVID-19 Presidential Task Force (PTF) to mobilise, implement and coordinate the multi-sectoral efforts for containment, treatment and prevention of COVD-19 cases (Ameh, 2020) [17]. Under such mandate, the NPF drew officials from several Ministries, Departments, Agencies and (MDAs). According to State House (2020) [18], the task force:

-

(a)

Provides overall policy guidance and uninterrupted assistance to the National Emergency Operation Centres within the NCDC and the MDAs in containment efforts to achieve national strategic objectives.

-

(b)

Enables the delivery of national and state-led control primacies.

-

(c)

Reviews and approves recommendations for effecting nationwide non-pharmaceutical interventions; school closure, social distancing, suspension of large gatherings and flight deferment.

-

(d)

Provides recommendations for direct funding and technical support to state and local governments in capacity building and strengthening.

-

(e)

Defines objectives and observes the progress in actualising the goals to meet the least prerequisites for satisfactory performance.

-

(f)

Engages the public in progress with the national response and related evolving developments.

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 Response Framework (Amzat et al., 2020) [3].

Furthermore, the NCDC was funded with USD 27 million for capacity building to facilitate an effective response to the pandemic (International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2020) [19]. Another USD 3.4 billion was provided to the authorities as an emergency monetary assistance package under the Rapid Financing Instrument by the IMF in April 2020 (2020) [20]. While the federal authorities are building isolation centres in Lagos and Abuja, they advised State authorities to strengthen the health facilities in their respective domain (Onuoha, 2021) [21]. Even before the outbreak of the disease, the NCDC trained its staff on molecular diagnostic capacities with assistance from the African Centre for Disease Control and was supported by the establishment of Emergency Operation Centre and molecular diagnostic laboratories to increase the operational capacity for diagnosing the disease (Alagboso and Abubakar, 2020) [22]. While the arrangements were underway, airport authorities implemented public health-air travel protocols. The protocol consisted of compulsory completion of forms by returnees from overseas (Dixit et al., 2020) [23]. Also, the returnees were mandated to undergo temperature checks at airports before moving into the country. Equally, the Aviation authorities strengthened surveillance at five international airports in Enugu, Rivers, Lagos, FCT and Kano to detect suspicious cases and safeguard control efforts. Having foreseen the impeding economic impacts, the government proposed monetary and stabilisation initiatives for economic resuscitation: a reduction in the public expenditure due to an expectation in revenue decline from crude oil exports and offering up to fifty billion Naira stimulus package to businesses severed by the pandemic (Nigeria's Federal Ministry of Budget and National Planning, 2020), injection of 3.6 million naira into the banking system, lessening the interest from 9% to 5% and ushering of a one-year moratorium on relevant Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) intermediations (CBN, 2020) [24].

1.2. National containment policies

Responding to the threats of the COVID-19 pandemic requires a combination of measures, including public sensitisation, legislation, social distancing, and imposition of lockdown (Li, 2021) [25]. The WHO issued public health advisories on the need to maintain hygienic practices, use a facemask and keep a physical distance of at least 1 m from others. The NCDC Connect Centre trained journalists, engaged media outlets, and conducted Event-Based Surveillance, involving engagements with the public to get the Nigerian public abreast of the state of containment and prevention efforts. The NCDC facilitated arrangements through its toll-free line, social media platforms (including automated WhatsApp messages), a particular website, and periodic online live sessions (Alagboso and Abubakar, 2020) [22]. With multimedia content produced in many languages focusing on different demographics, it collaborated with governmental, non-governmental organisations, and telecoms to enlighten the public on safety and preventive measures, informing the public and addressing misinformation about the disease.

As part of the WHO guidelines to manage the pandemic, the option of social distancing was rigorously implemented and propagated. As described by the NCDC, social distancing aims at reducing the proximity of approximately six feet or 2 m between people and avoidance of mass gatherings. However, if this distance is maintained, infection and spread are reduced (Lipsitch et al., 2020) [26]. All forms of mass gathering for any purpose were also banned. A restriction of movement and the closure of public spaces, including schools, offices, places of worship, recreational centres, and private organisations, also came into play. However, compliance with these measures became problematic as many failed to comply due to either defiance, unwillingness, or search for economic sustenance to address the unfolding economic hardship.

As a significant public health-policing strategy adopted worldwide, every affected country implemented lockdown as the most feasible and proactive method to reduce transmission (De Vos, 2020) [27]. It is a public health tool that seeks to minimise the possibilities for an infectious disease agent to spread among people and curb transmission speed. It successfully lowered the incidence rate of the pandemic in countries that enforced it relative to those that did not (Alfano and Ercolano, 2020) [28]. Combined with other factors such as the healthcare system's capacity, these strategies also played a significant role in the difference in contagiousness and severity. In India, the infection rate decreased to 50% from 3 to 6 days a week due to the effectiveness of the lockdown (Gupta et al., 2020) [29]. As arduous and daunting as the lockdown was, it protected the African countries against public health crises arising from the pandemic (Kitara and Ikoona, 2020) [30].

Further to the above, the Nigerian government announced the first phase of the COVID-19 restriction measure branded ‘fourteen-day lockdown’ on March 27, 2020, with the enforcement beginning in the Federal Capital Territory Abuja, Ogun and Lagos State on March 30, 2020 (Mbah, 2020) [31]. Hence, the cessation of interstate movements, closure of communities, and adverse effects on Nigeria's tourism. A few weeks after, this order saw the emergence of COVID-19 stay-at-home directives by state governors in all Nigerian states and cities, including Ilorin (the focus of this study). At the end of the first phase, there was an extension by another two weeks, making the period four weeks (CNBC Africa, 2020) [32]. From the beginning in Kwara State, the government, through the state's COVID-19 Task Force, initially introduced a total lockdown of Offa Town on April 07, 2020, after it had recorded the first two cases a day before (The Cable, 2020). Subsequently, the total lockdown of the state for 14 days commenced with the exemption of those in the production and facilitation of essential goods and services and markets selling foods and medications to open three times a week (on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays), between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. (Premium Times, 2020) [33].

Barely after the lockdown started, the Nigerian government, on March 30, 2020, promulgated COVID-19 law, which legalises the restrictive measures imposed. The law titled ‘COVID-19 Regulation, 2020’ came into being under Section 2, 3, 4 of the Quarantine Act20041 to declare COVID-19 an infectious disease and make regulations that include: restriction of movement in the FCT, Ogun and Lagos State, continued operation of Lagos seaports, suspension of (both private and commercial) passenger aircraft, provision of relief materials among others (Aljazeera, 2020) [34]. In furtherance of the above, police personnel were deployed to enforce the restriction. However, despite the COVID-19 regulation, there were pockets of violation nationwide.

1.3. Policing the pandemic: enforcement of lockdown

Regarding the global involvement of the police to enforce partial/total lockdown, the NPF deployed its personnel nationwide to ensure the COVID-19 Regulations are strictly enforced. The deployment brought changes to police operations in the stationing of officers at checkpoints and transit routes and presented challenges to the police regarding citizens' compliance, sustenance of cordial police-community relations, officers' safety (availability of personal protective equipment) and training of personnel in managing emergencies (Bonkiewicz, and Ruback, 2012) [35]. Nonetheless, tactics used are dependent on the existing citizens’ behaviour, the nature of the emergency and issues peculiar to policing in a jurisdiction. Just as the severity of the pandemic and the concomitant response varied, policing reactions differed (Godwin, 2020) [29]. As observed in South Korea and Russia, the tactics were non-democratic and technology-based (Dudden and Marks, 2020 [36]; Magnay, 2020 [37]) or in China, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, where traditional/militaristic models of policing prevailed (Li, 2020 [7]; The National, 2020 [38]) as against populist ideal of policing obtainable in Italy during the lockdown (Scalia, 2020) [39]. However, the current pandemic has impacted policing operations in three ways; enforcement of new laws to control public spaces, use of new strategies such as drones and smartphone devices and deployment of new personnel (Godwin, 2020 [40]; Mawby, 2020 [41]).

Given the mandates of the NPF to promote public safety and security of life and properties of citizens as stipulated by extant laws, the implementation of lockdown brought about the placement of police officers at strategic locations and interstate border areas across the federation. Thus, the NPF issued guidelines to its officers on protective measures, engagement with citizens and disease victims, prevention of misinformation and rumour, medical emergencies and management of public order (Nigeria Police Force, 2020) [4]. Despite the instructions, the personnel's interaction fell short of acceptable standards. There were instances of personnel mistreatment of citizens who attempted violation of the lockdown directives. Even before the commencement of the lockdown, the Nigerian Police had strained relations with the public, thus, diminishing the cooperation needed for the enforcement of the stay-at-home directives. The police have often been subjected to public scrutiny and condemnation due to violation of human rights, lack of due process and absence of credibility in discharging their statutory duties.

Police operations in Nigeria are problematised with corruption (Ifeanyichukwu, 2017) [42]. The operational officers charged with the responsibility of maintaining law and order, patrolling communities, investigating crimes, apprehending and processing suspects and controlling traffic are always captured in the news headlines for forms of unethical practices such as demanding bribes, extortion of motorists at both legal and illegal checkpoints, formation of unlawful checkpoints and roadblocks, falsification and manipulation of evidence (Nasir, 2017) [43]. In addition to the corrupt practices, brutality and human rights abuse; torture for arrest and criminal investigations. They are dominant issues when discussing the police, particularly when handling violent cases. During the four weeks of nationwide lockdown, these issues also prevailed: violation of human rights, corrupt practices, and low adherence to government directives. The police officers deployed turned checkpoints into cashpoints where they rake in money; travellers and motorists in different parts of Nigeria paid between 200 naira and 2000 naira to cross from one state to another (Guardian, 2020) [5]. The extra-judicial killing of citizens was also among the excesses of the security agents. During the first two weeks of the lockdown (from March 30 to April 13, 2020), eight incidents of extra-judicial killing were reported, leading to 18 deaths of people. Additionally, reports of 33 incidents of torture and inhumane treatment, 19 incidents of illegal confiscation of properties, 13 incidents of extortion and 27 incidents of violation of the right to freedom of movement. The report also indicated that the human rights violations recorded resulted from excessive use of force, abuse of power and non-adherence to human rights laws and best practices by law enforcement agents (National Human Rights Commission [NHRC], 2020) [44].

1.4. Theoretical consideration: Policing the Pandemic and procedural justice theory

Procedural justice is a widely known practice in policing and criminological discourse based on the thrust of police-public relations. It serves as the basis for evaluating police performance and their treatment of the citizens (Mazerolle et al., 2012) [45]. It is also concerned with police decisions that are made on fair and just practices that facilitate public support when citizens feel the police treat them with courtesy and dignity. The quality of and public satisfaction in police treatment are critical components of the procedural justice paradigm of policing (Akinlabi, 2015) [46]. To provide the level of service that the public expects from the police, officers must be courteous and respectful, treat people with dignity and respect, allow people to express their concerns, and act as the neutral and unbiased enforcers of the law in every encounter or interaction with citizens (Davies et al., 2014) [47]. The use of procedural justice aspects in police-citizen interactions has proven to be more useful and individuals have expressed more satisfaction with the interactions and results of such encounters as a result (Mazerolle et al., 2013) [48].

As a basis for policing and law enforcement, procedural justice offers explanations for why people obey the law. It explains that the conformity of people with rules and regulation of a constituted authority is driven by instrumental elements and normative factors (Tyler, 1990) [49]. The instrumental view argues that compliance with an authority's rules is motivated by the fear of such authority punishing violators in the event of disobedience. In this view, people make a cost-benefit analysis by weighing the gains of violation and the potential punishment if apprehended (Radburn and Stott 2019) [50]. A deterrence threat or pleasurable attachment exogenously influences the decision to comply with the law. Conversely, the normative viewpoint explains people's obedience is motivated by their objective judgment that such law is reasonable, fair and appropriately enforced (Stott et al., 2020) [51]. Citizens tend to cooperate with the police when they believe that the law being enforced is rational and its purpose is for the public's good.

Furthermore, the policing of COVID-19 pandemic has been a subject of policing attention and concern in academic discourse. From personnel safety, maintenance of police-community relations to manners of enforcing policing measures, the pandemic has influenced the police operation and generated academic debates (Bonkiewicz and Ruback, 2010 [52]; Bonkiewicz and Ruback, 2012 [35]; Brooks and Lopez, 2020 [53]; Jones et al., 2020 [54]; Laufs and Waseem, 2020 [55]). However, the NPF issued to its officers a code of conduct to enforce the nationwide lockdown (Nigeria Police Force, 2020) [4], which prompted the inquiry on how officers should have handled the task of enforcement. Thus, procedural justice theory addresses the inquiry. Amobi et al. (2020) [56] observed that compliance with the lockdown directive in Nigeria resulted from normative thinking rooted in the trust people had in opinion leaders and medical experts on the threats of COVID-19 even amidst conspiracy theories being coined by different quarters. If the conspiracy theories are accepted and the trust in medical experts is non-existent, they will be less disposed to abide by the lockdown orders (Mian and Khan 2020) [57]. Thus, they considered such compliance a moral obligation for the safety of all and sundry. However, the authorities will tend to achieve instrumental compliance in such a situation where the citizen will likely disobey the law. The use of instrumental compliance was the case during the COVID-19 lockdown in Nigeria as a force was used in policing the movement of citizens: officers abused power and violence ensued between police personnel and the citizens. Hence, the negation of the principles of procedural justice that the personnel is expected to uphold (Amnesty International, 2020) [58]. The police-citizen interaction was unethical from the police's end as officers were involved in a series of extortion, bribery, and extra-judicially killing during the four-week-long lockdown (BBC, 2020 [59]; NHRC, 2020 [44]). Consequently, the cordial police-community relationship that is central to law enforcement became absent, and the public image of police was further battered. Scholars have argued that the struggle the Nigerian police encounter in achieving normative compliance is a product of low public confidence, flagrant abuse of human rights, gross misconduct, and police corruption (Aborisade and Fayemi 2015 [60]; Akinlabi 2020 [11]). Therefore, in line with the procedural justice theoretical framework, citizens will not willingly comply with the lockdown directives. As noted by previous research, compliance with law and citizens' support for the police are fueled by public trust and confidence (Cheng, 2020 [61]; Sun et al., 2016 [62]; Wang and Sun 2020 [63]).

1.5. The current study

The emergence of the novel COVID-19 pandemic that led to the lockdown of cities, particularly the hotbed zones across the world, has incited several academic studies that examined government policies and the roles of the police in mitigating the scourge and codes of operations for police officers concerning the lockdown directives (Aborisade and Ghadabo, 2021 [64]; Biswas and Sultana, 2020 [65]; Farrow, 2020 [66]; Mawby, 2020 [41]; Onuoha, 2021 [21]; Scalia, 2021 [39]; White and Fradella, 2020 [1]). While some of these studies reported public support and cooperation with the police (Farrow, 2020 [66]; Scalia, 2021 [39]), Richard (2021) [67], Aborisade and Ghadabo (2021) [64] and Onuoha (2021) [21] observed instances of unethical police practices. However, none of the available literature extensively examined the contributions of citizens’ behaviour and police conduct in the (non)compliance with the lockdown directives.

Hence, this study seeks to examine public (non)compliance with the lockdown orders vis-à-vis possibilities of unethical policing in the enforcement of the directives in Ilorin, Nigeria. It aims to investigate the reasons for violating the directives and the illegal police practices perceived during the lockdown. Also, the study focuses on the police as the principal law enforcement agency in Nigeria, the allegation of illegal police practices, citizens' violation of the lockdown directives and implications for the management of future pandemics. Upon completion, the study will provide insight on what influences (non)compliance with the directives and, at the same time, (in)validate the allegations of police illegalities in policing the pandemic with the view of advising stakeholders and the government on areas to consider in formulating pandemic management policies. It will also add to the literature on pandemic policing and citizens’ behaviour.

2. Methods

Due to a couple of factors, this study adopted a qualitative model. Firstly, the controversies and complications attached to pandemic policing in Nigeria and the rest of the world and secondly, a bid to obtain the citizens' insights concerning their (non)compliance with and police involvement in the enforcement of the unprecedented lockdown rather than the usual conversations on unethical police practices in Nigeria. Additionally, the model allows gathering inductive information from a small population within a short period and gaining an in-depth understanding of the participants’ view of the subject matter under study (Lune and Berg, 2016) [68]. This section, however, discussed the methodological configurations of the study upon three structures: an explanation of the study setting, participants, sample formation, and inclusion criteria, an overview of data (interview) collection protocol and the step involved and lastly, identification of statistical analysis methods.

2.1. Study settings

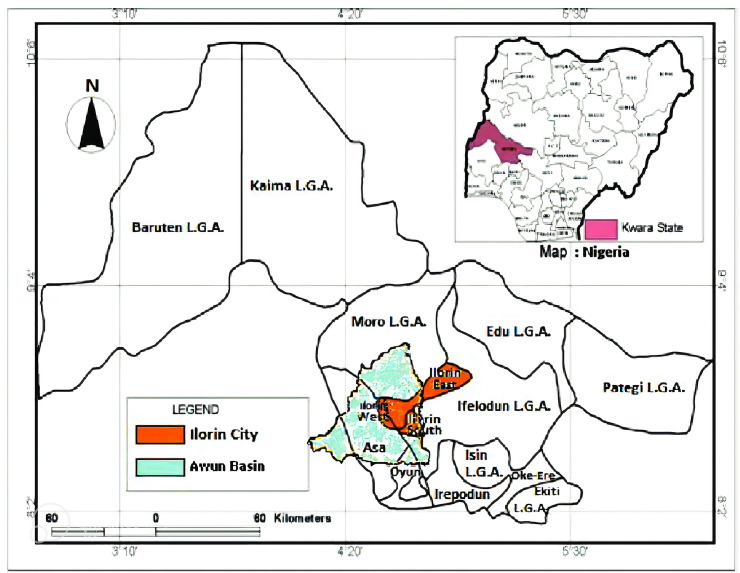

The study was carried out in Ilorin, the capital city of Kwara State, located in the Northcentral geopolitical zone of Nigeria. Ilorin has three Local Government Areas: Ilorin South, Ilorin East and Ilorin West. It is an ancient Muslim society populated by Yoruba and Hausa/Fulani ethnic groups (Na’Allah, 2009) [69]. According to World Population Review (2021) [70], the population of Ilorin currently stands at 973,671. Geographically, Ilorin city sits at the centre of Kwara State, Northcentral, Nigeria. It directly connects to the other parts of the state: Kwara North and South (according to senatorial district delineation) (see Fig. 2 ). Its distance from the country's FCT, Abuja and commercial hub, Lagos, is 500 km and 306 km, respectively. It directly connects to major cities and transport hubs in the country such as Onitsha, Port-Harcourt and Asaba (in South East/South), Abeokuta, Lagos and Ibadan (in South West), Kano, Niger, Kogi, Kaduna, Plateau, and Abuja (in the North).

Fig. 2.

The map of ilorin within kwara state (raheem, 2011) [71].

Commuting between Ilorin and these places is direct. Travellers coming from the southwestern parts and going to the northern parts of the country pass through the city and vice versa (Babatunde et al., 2007) [72]. Within Kwara State, it lies in the centre as it joins Kwara South and Kwara North (according to senatorial district delineation). It maintains an uninterrupted travel route with Offa (the first location in the state to record COVID-19 case) and towns such as Igbaja, Jebba, Kaiama, Esanlu Asa, among others that connect the state with its neighbours. Therefore, the option of Ilorin can be said to suitably facilitate the violation of lockdown directives (travel) within Kwara State and with other States, which this study seeks to examine.

2.2. Population and sampling technique

The population of this study was the residents of Ilorin city who are between the ages of 18 years old and above, including those who travelled (either as passengers or commercial tour drivers) during the COVID-19 lockdown period between March 30 to April 28, 2020, and operational police officers who were deployed to enforce the lockdown. Sampling allows the selection of a portion of a population to represent the population (Ritchie et al., 2003) [73]. Hence, this study adopted four sampling methods: convenience, referrer, venue-based, and purposive to recruit participants. At first, an invitation note seeking the participation of individuals under the considered population was posted on social media platforms (including Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp groups, etc.), dominated by Ilorin residents (Richard, 2020) [67]. Those who showed interest were sent a consent form with details of the purpose and implications of the research and their rights as participants to peruse and sign. Subsequently, those who returned a signed consent form (via the social media inbox) were reached through their submitted detail and selected using a convenience sampling method.

This method produced thirty-five participants for the study. The convenience method was successful in that some participants selected through the process also referred the interviewers to Twenty-five people (who did not have social media presence) for participation. The author's acquaintance with the city and venue-based sampling method identified five major commercial bus terminuses. These terminuses were selected due to their large size, the number of vehicles in operation, and the frequency of transportation activities. They include Offa Garage, Unity, General, Geri Alimi, and Maraba terminus. The selection aims to survey the commercial tour drivers whose work borders on travelling and can serve the purpose of this study by airing needed insight on citizens' movement and police conduct. The convenience sampling method was also employed to select 25 participants (Creswell 2013) [74]. Given the fact that police personnel who were involved in the enforcement of the lockdown order were part of the study's target population, purposive sampling method was adopted to recruit them for participation. Initially, five major police stations in Ilorin were surveyed to enable operational police officers who actively engaged in the enforcement of lockdown orders to participate in this study and clearly understand (non)compliance with the orders and the challenges encountered. Thus, efforts were made to meet the Head-in-charge of these stations surveyed, but such efforts proved fruitless as none of them was responsive. However, five officers across the stations willingly signified interest in participating in the study unofficially and voluntarily. The authority did not sanction their participation; it was out of their volition.

In total, 90 individuals were recruited and interviewed. The age range of the majority of the participants was ages 18 and 25. It was due to the involvement of students and young individuals of this age bracket residing within the University of Ilorin community during the lockdown period. Part of the 9% unemployed population was among these students. Concerning the commercial tour drivers, all the participants are males, while an overwhelming majority (80%) are married. In addition, 68% of them were age 50 and below, while 56% had at least 11 years of driving experience. Furthermore, all the police personnel interviewed have a tertiary education certificate comprising a Bachelor's Degree, Ordinary National Diploma and Higher National Diploma. This result suggests that they are well educated. However, almost all of them (80%) had spent an appreciable number of years in service, spanning at least six years.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of participants.

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Ilorin Residents (60 participants) | |

| Age (Years) | |

| 18–25 | 17 (28.3) |

| 26–35 | 7 (11.7) |

| 36–45 | 12 (20) |

| 46–55 | 8 (13.3) |

| 56 – Above | 16 (26.7) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 35 (58.3) |

| Female | 25 (41.7) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 13 (21.7 |

| Married | 47 (78.3) |

| Employment | |

| No Employment | 9 (15) |

| Artistry/Farming/Trading/self-employment | 32 (53.3) |

| Private Firm Employment | 7 (11.7) |

| Government Work | 12 (20) |

| Highest Educational Level | |

| First School Leaving Certificate (FSLC) | 8 (13.3) |

| Ordinary Level Certificate | 27 (45) |

| Tertiary Level of Education | 25 (41.7) |

| Commercial Tour Drivers (25 Participants) | |

| Age (Years) | |

| 30–40 | 5 (20) |

| 41–50 | 12 (48) |

| 51–60 | 6 (24) |

| 61 – Above | 2 (8) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 100 |

| Female | 0 |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 5 (20) |

| Married | 20 (80) |

| Highest Educational Level | |

| First School Leaving Certificate (FSLC) | 10 (40) |

| Ordinary Level Certificate | 10 (40) |

| Tertiary Level of Education | 5 (20) |

| Driving Experience (Years) | |

| 0–5 | 3 (12) |

| 6–10 | 8 (32) |

| 11–15 | 10 (40) |

| 16 – Above | 4 (16) |

| Police Personnel (5 Participants) | |

| Age | |

| 25–35 | 1 (20) |

| 36–45 | 1 (20) |

| 46–55 | 3 (60) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 3 (60) |

| Female | 2 (40) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 1 (20) |

| Married | 4 (80) |

| Level of Education | |

| Tertiary Level of Education | 5 (100) |

| Years of Service | |

| 0–5 | 1 (20) |

| 6-10 | 2 (60) |

| 11 – above | 2 (20) |

2.3. Data gathering procedure (interview protocol)

The study used a semi-structured interview to gather information from the participants. Due to the prevailing public health situation, some participants opted for an electronic form of the interview, which was done via phone/video calls, while face-to-face interviews with the police personnel, commercial tour drivers and the majority of the citizens. The face-to-face interview facilitates the collection of more details through body language (Scarborough and Tanenbaum, 1998) [75]. The author recruited two research assistants to ensure that the interview process went seamlessly. The interviews occurred during the day and lasted for a month; September 2020 and each of them took at least 30 min. Due to the proficiency level of the participants, some of them who were not proficient in the English language opted for Yoruba language and the transcript was interpreted to English. The rest were interviewed in English language. In adherence to COVID-19 safety protocols, the researchers and the participants properly fitted face masks adhere to the physical distancing protocol during the interviewing process (for the face-to-face interview). In line with research ethics, the study maintained the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants and their revelations.

In dissecting procedural justice theory, participants were asked about their experience with the police at checkpoints, border areas, and highways during the lockdown, factors associated with their (non)compliance, strategies used for movement despite the movement restriction and escape in case of arrest. Examples of questions asked included the following: “do you believe that there was COVID-19 in Ilorin before and during the lockdown?‘, ‘do you think the lockdown was appropriate to reduce the spread of the pandemic?‘, ‘did you move during the lockdown outside the approved period?’ ‘How did you escape arrest?’ ‘How did you enforce the lockdown?‘, ‘Did you experience or observe any incident of police officers collecting bribes from, brutalising or maltreating people when enforcing the lockdown?‘, ‘What were the challenges you faced during the enforcement of lockdown?‘, Any problem you wish to inform the government of?

2.4. Analysis plan

In the current study, I examined the reasons associated with citizens' (non)compliance with lockdown directives and unethical behaviour exhibited by police personnel towards the citizen in the enforcement of the lockdown directives in Ilorin, Nigeria. I adopted an inductive thematic analysis approach that scrutinises qualitative data regarding people's perceptions of a particular phenomenon (Braun and Clarke, 2006) [76]. It entails familiarising the data gathered, generating code, naming and understanding themes, and making inferences from data transcripts. The transcripts of the interview were reviewed many times to ascertain common themes. Codes were allotted to the needed information. The appraisal of the coded transcript in terms of resemblances and variation indicated connections between the codes that described each theme. Accurate comments explain the interviewees' opinions on vital themes (Nelson, 2018) [77]. The analysis process commenced with reading through the transcript, observing common and different themes, and putting together an initial coding protocol. The codebook contained the participants' narration of the observed human rights violation (brutality), unjustified use of force, the corrupt stance of police personnel, and their reason(s) for violation despite the stay-at-home order in place.

3. Results

In this section, I explained the participants’ knowledge of COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, the need to comply with the resultant lockdown and its suitability and their encounter with police officers in the enforcement of the lockdown. The opinions on the themes in this section were both general and individualistic. Their insights concerning police bribery and violence constituted part of what is generally known as police illegalities, particularly in the Nigerian context. Due to the non-availability of a universally-accepted definition of police illegality, this study relied on the following issues to describe the public encounter with the police personnel: maltreatment, offering/taking bribes, verbal threat, intimidation, sexual abuse and physical assault. For clarity, this study tagged the five police officers interviewed as P1, P2, P3, P4 and P5. Finally, the themes considered are COVID-19 Pandemic Outbreak, Appropriateness of Lockdown, Restriction on Movement, Violations and Strategies employed, Mechanisms for Enforcement, Bribery and Corruption, Brutality and Violence, Challenges encountered by the Police, Concerns over the use of lockdown.

3.1. COVID-19 pandemic outbreak

Central to the compliance with the lockdown directives, this study surveyed the participants' beliefs about the disease outbreak in Ilorin, Nigeria. The majority (72.2%) believed that there was COVID-19 pandemic in the city when the lockdown commenced, while 16.7% maintained neutrality and 11.1% disagreed. Knowledge, awareness and first-hand experience appear to have informed and shaped the opinion of these participants. In consistency with Ozdemir et al. (2020) [78] most of them believed that the pandemic existed because of government policy response, health authorities’ advisories, and media reports of happenings in the country and the rest of the world. A trader said that:

‘I believe that there was COVID-19 pandemic even before when the government said should stay at home. COVID-19 is real. We can see people dying in other countries. There is no reason to think the virus won’t be in Ilorin. It is impossible because the virus spreads faster. You can see how our governments are handling the matter. If there is no COVID-19, you think the government will close schools?’

Additionally, having relatives and acquaintances who contracted the diseases influenced the participants’ views. A government worker said that:

‘COVID-19 is very real because I have friends who had infected people; a family friend too contracted it. I saw people being taken to Isolation Centre. The figures keep going up daily, as seen from the NCDC record. Since we were lax with pre-COVID-19 measures, COVID-19 was impossible not to be in the country. The safety precaution released by health officials is enough to tell us the disease was in the country when the lockdown started’.

Contrarily, the opinion of a few participants (13.1%) indicated their disbelief in the pandemic outbreak. Based on public mistrust, these participants believed that the authorities ployed the stay-at-home order to embezzle public funds. Some even thought it was a trick by the government to source money from foreign governments and international organisations. An artisan opined that:

‘I do not believe that there was COVID-19 in our country when the lockdown started. I believe that those figures we see released by the NCDC were bloated out of proportion to steal money again. No single person knows someone who got infected. This is impossible in a gossip-loving city like Ilorin’.

As the opinions above denote mixed reactions, the infection of relatives/acquaintances and distrust in the government shaped the majority's opinion.

3.2. Appropriateness of Lockdown

As most of the participants numbering 65, believed in the pandemic outbreak in the city, they demonstrated an appreciable understanding of lockdown as an effective measure to reduce the pandemic spread. Their belief resulted from the national preparedness and containment efforts intensively pursued and sensitised to the public via various media platforms and channels. They believed that it was necessary and appropriate for the government to impose it. A businessman said that:

‘The lockdown indeed was the best way to prevent the pandemic from spreading because, as human beings, we are so fixated with our daily routine, but this lockdown keeps people at home. It limits the number of people gathering at a particular place in time and keeping people at home is the only way out in a populous country like Nigeria. It restricted movements and, in that way, curbed the spread of Coronavirus’.

In corroboration to the above, another participant noted that:

‘COVID-19 spread through droplets of an infected person, so it was important to stay at home and embark on the lockdown for at least two weeks. This will truly reveal who is and is not suffering from the virus since it takes two weeks to detect it. It will prevent further transmission and help health workers manage and treat the manifested cases’.

These accounts show how the residents perceived the pandemic existence and the necessity of imposing a lockdown to mitigate the spread. From the revelations, it is deducible that they supported the lockdown measure.

3.3. Restriction on movement, Violations and Strategies employed

While more than half of the participants (57%) obeyed, a reasonable 43% flouted the state/national curfew on various factors. The palliatives the government claimed to distribute were insufficient to cater for their needs. A trip to their hometown to meet their family and quest for basic materials to aid livelihood are significant reasons. Meanwhile, factors such as visitation to people and issuing a license to citizens by police authorities to move around also played out in non-compliance with the curfew orders. However, these violators devised unconventional means like trekking through the bush and bribing police personnel to travel through the border routes. A trader noted that:

‘I travelled because I was desperate to get money to feed the family. As you are seeing me, I have four children at home to feed not only that, I have aged parents I must cater for. It was necessary for my livelihood and that of my family. I am into foodstuffs trade and travelled to a neighbouring state to get food supplies. I needed to run my business, and it is essential to eat, as you know.

When asked further about the strategy for movement, the participant said that:

‘I boarded a cab from town to town and trekked to bye-pass the security men. In some cases, I was caught and asked to pay money to pass, and I paid; it ranged from 500 naira to 1000 naira. I use the bush path too whenever I am not with much money. If I use the normal route I do use, I will pay the police officers and it would affect my plans. With that, I tried to keep myself safe in all these cases by distancing myself from the crowd, washing my hand and using my face mask’.

Apart from economic reasons, the violation was also attributed to academic and personal reasons. A male student noted that:

‘I travelled to my house in the university community to continue the research work I started before the pandemic. I could not afford to waste the fund, resources and energy I had invested in it. When I returned home, I had a course to help my mum with something important and people were travelling without any hindrance, so I felt why not? I travelled three times during the lockdown’.

Furthermore, the participant was strategic in his travelling by monitoring the movement pattern of the bus and preparing himself with sufficient money to bribe his way at checkpoints. He noted that:

‘Anytime I want to travel, I will prepare myself with more money because the transport fare was high then. I did not use the motor parks because the buses moving were few. They were only parked. I stayed at a spot far from the usual park to wait and board any bus moving. Once I see any bus approaching me, I would enter and pay regardless of the price. The drivers usually pay the police officers nothing less than 2000 naira at border routes. We passengers too paid 200 naira each. It was tough, especially with the security personnel mounted on the road, but sadly corruption being what it is in the country, some palm greasing resolved it’.

Furthermore, many (64%) of the commercial tour drivers complied with the lockdown directives. Those who defied the orders did it based on economic necessity. With the travel ban's severance of the transportation industry, they justified their disobedience and narrated how they had their way at checkpoints. A driver described that:

‘We could not work as we wanted. The pandemic affected us a lot. Also, passengers didn’t come to the terminus to travel as they usually do before Coronavirus. Only a few who are students of the University of Ilorin and those travelling to a nearby city, Ibadan, came. I transported them to their destination because I was broke. When we got to the Kwara/Oyo state border, there was traffic congestion. So, I alighted from my bus to know what had happened. Then, I saw a private car owner and commercial tour drivers from other states like Ekiti and Osun negotiating their way with 2000 naira, some with 3000 naira. That was when I knew I would pay nothing less than 2000 naira. I paid 2000 naira and was allowed to go’.

From the narrations above, violation of the curfew order stemmed from economic reasons and other factors such as academics, as noted by a male student. However, most of the violators are those in the informal sector who live on daily earnings. Government workers and private firm staffs appear to be compliant, perhaps because there were salaried. As private enterprises were shut down, some paid their staff half salary or fully in advance. Thus, no government or private firm worker who participated in this study violated the movement ban on economic grounds.

3.4. Mechanisms for Enforcement

Enforcement of COVID-19 lockdown directives requires tactics peculiar to the situation, which must not violate human rights. These tactics include advice and warning to the public, barricades, and suppression tactics, which help frighten violators without identifying and arresting them. The suppression tactics involve patrol, checkpoint, security guards/dogs, closure, etc. P1 noted that:

The lockdown was enforced by posting men of the police force to the strategic points on the road, routine visits, supervision and close monitoring by the superior officers. Part of the mechanism used includes mounting roadblocks, blockage of interstate movement, and setting up a special operational order where many police officers were drawn from different police departments and posted to implement the lockdown order.

In addition to the above, P4 added that:

‘Before the lockdown started, we advised people to stay indoors and warned that anyone found moving outside the time allowed for movement shall be penalised. We used barricades, blocking of roads, and detention of violators to restrict movement. Those we arrested were taken to the police station, detained and released in the evening. We did not allow anybody to move except the medical personnel and other essential workers. As journalists were part of the exempted set of people, they were not allowed to move freely unless they had identity cards, hand sanitisers, facemasks, and other necessities.

3.5. Bribery and Corruption

Out of those who violated the curfew directives constituting 37 (43%), 25 observed or experienced acts of extortion and usage of money to facilitate their movement across communities, cities and states involving Ilorin. An interview with 85 participants comprising citizens and commercial tour drivers explained the extortive tendency of police personnel. In agreement with the literature that policing in Nigeria is characterised by corruption in the form of extortion of road users at both legal and illegal checkpoints (Nasir, 2017) [43], these participants narrated how they used money ranging from hundreds of naira to thousands of naira to have their way despite the curfew. A private firm worker said that:

‘To be honest, I saw police officers collecting bribes. In fact, they collected 200 naira. They no longer collect the normal 50 naira they collect; they now collect 200 naira to allow people to pass. These are what was obtainable. My father experienced it; I was in his car when it happened. We were going to pay a visit to someone in Osun state who gave birth and when we got to a checkpoint, the police officer said, “you don’t suppose to go out but since you have gone out, you have to pay us” we had to give him 100 naira and he replied, “Haha you don’t know it is 200 naira?” We don’t know and we gave him 200 naira. It was as if they had already fixed a special price’.

Another participant (a tour driver) who travelled during the lockdown period also asserted the extortive tendencies of police officers deployed to the border routes. He noted that:

‘During the lockdown period when we were struggling to pass across borders, the money the police supposed to make (through bribery) within years was made within that one month; they collected a lot of money. The police will charge you. They will say you know there is a lockdown before you can cross the border, you will have to pay 5000 naira and you will be negotiating it to around 2000 naira and we will have to pay it’.

In reaction to the claims of bribery, the police officers interviewed were divided. Three out of them never denied the cases of bribery; they blamed it on the routine nature of road users. A police officer reacted:

‘You cannot blame the police only for bribery during the lockdown because people too are part of the problem. It is a normal routine. You will see a motorist coming and by the time he reaches the checkpoint, he would not bother to allow the police to do their job. Before you know it, you would see him offering money to the officer in charge. Passengers in the bus will be the ones encouraging him to offer a bribe because they want to reach their destination without any delay’.

Contrarily, P3 denied the act of bribe-taking by the police officers. The P3 asserted that:

‘We did not collect any bribe to allow people to pass because it will affect us if we do. If we collect bribes, people will pass, the virus will spread through the money given to us and it may affect our family members, too and the money we collect will be used for treating any problem that may arise. None of our officers collected bribes as far as Ilorin is concerned.

The accounts above from the participants cutting across the three groups of the participants address the issue of whether or not bribery and extortion by police personnel occurred during the lockdown.

Noteworthily, the act of bribe offering/taking was more obtainable as participants’ accounts indicated a willingness of the road users to give the bribe to have their way. Interestingly, this line of thought was corroborated by a police officer who opined on citizens’ interest in disallowing the police to do their job while offering money in replacement.

3.6. Brutality and Violence

Interviews draw out detailed information (based on experience and witness) on the encounter of citizens with the police personnel, particularly at the checkpoints and border routes. Specifically, 10 participants ventilated their grievances over what they termed as police brutality, such as verbal abuse, attempted sexual harassment, maltreatment and physical assault. Participants voiced out how the desire of the police to extort made them have violent encounters with commuters. If commuters fail to succumb to the demand for a bribe by police officers, it will lead to brutality, which will be the punishment for not cooperating with the police. A female artisan narrated that:

‘The police assaulted a lot of people. A police officer even threatened to harass me sexually in front of my father because I confronted him about why he was demanding money from my father’.

Another participant who witnessed maltreatment and physical assault by the police noted that:

‘I did not experience any violence from the police, but I saw some people being taken to the police station by the officers, but it was after they had been slapped and verbally abused by the officers. It was seriously pitiful’.

Another participant who, alongside his team members, had the license to move within Ilorin city for community outreach observed a case of inhumane treatment and narrated that:

During our outreach project, I saw people without a license being arrested and watched as a bystander. The police told those people to wait, but they did not wait. They (the police) were pursuing them, but they later waited. So, as the police officers approached them, they did not ask why they did not wait and why they disregarded the order. They just carried them into their van by pushing’.

Reacting to the allegation of violence, the police officers interviewed opined that citizens' defiance must have caused any violent encounter with the police to enforce the restriction, which they found unfavourable. They also noted that the police, too, suffer from such ugly incidents as they reduce police legitimacy. Those who experienced inhumane treatment from the police were unsatisfied with the lockdown policy, mainly due to the government's insufficient provision of relief materials. P2 commented that:

‘The case of brutality reported in the media might be true; people are angry. They are unhappy because the government did not do what the masses expected before introducing the lockdown, so they may violate it. The police will respond with minimum force as stipulated in our laws during the process. If the police officers were not harsh, people would disobey. We used force on them, which is necessary to achieve compliance’.

From the revelation above, it is clear that the use of minimum force at times leads to violence. The power to use force is a product of the social contract between the police and citizens. Citizens sacrifice their right to use physical violence and delegate it to the police to protect society (Reiman, 1985) [79]. Therefore, according to the police officer justifying the use of force, such force was needed when there was a reasonable apprehension of disobedience. P5 commented that:

‘If the police carry out the full enforcement of the lockdown order, it is termed brutality. Whereas when we had another report of road users commuting the road freely, the police are said to be compromised. The civilians have a problem with the use of weapons by the police. They even provoke by shouting to a police officer, “shoot me if you can … do you even have bullets in your gun” and violence might ensue during the process. You have to ignore the provocation and apply minimum force on them’.

From the views expressed above, police violence emanated from several issues stemming from the police officers and government: disregard for human rights, wrong policing orientation and the need to achieve compliance with force. The government's inability to effectively address the lockdown-induced socio-economic burden fueled anger in citizens, thereby positioning them to violate the movement ban and encounter violence in the process.

3.7. Challenges encountered by the police

The management of public health crisis by the police is a multifaceted and complex task that requires perseverance, proper regard for human dignity and adherence to rules of engagement and administrative guidelines set out to achieve public compliance. In times like this, police officers face challenges, mainly when human rights issues are involved. The challenges cut across the resistance to order by the public, issues of police welfare, restiveness of citizens and mistrust for authorities. P1 noted that:

‘It was a tough call because many police officers on duty were not protected. Our welfare was not properly taken care of and many people are lawless. I had to imbibe the habit of restraining myself and painstakingly persevered against many insults passed down by people who contravened the lockdown order. We faced the challenge of lecturing people on the magnitude and dangers of the pandemic; we had to persevere. Although people obeyed and followed the set out COVID-19 guideline in the first instance but a disregard for the order started because the lockdown order was strange, as many complained of the economic effect and they began to disregard the order, thereby making it a difficult task for the police to execute’.

P5 noted that:

‘Identification of exempted people was part of the challenges we faced. People were moving, and some were claiming to be medical workers and judicial officers. You will see a car coming with a laboratory coat hung inside it; you will think those people coming are medical workers, so you will not query them because they are part of the exempted set of people allowed to move. The problem here is that when the illiterates see these people moving, they will want to move, which gave us a big problem’.

The experience of the police officers in the enforcement of the curfew order was fraught with the problem of citizens' compliance and ignorance. Citizens' defiance, which was connected to their inability to cope with the unprecedented lockdown was a central factor. Also, ignorance of the basics of policing the movement of people, particularly details on the exempted set of people (frontline workers), influenced citizens’ behaviour as some, according to the police were influenced into disobedience by mere observance of the passage of frontline workers.

3.8. Concerns over the use of lockdown

Citizens, tour drivers and police officers expressed concerns and displeasure over how the stringent lockdown was used to contain the pandemic. They aired their concern with emphasis on insufficiency in relief materials, illegal police practices, the porosity of border routes, incompatibility in approach, and government negligence. A farmer noted that:

‘The way the government enforced the lockdown was wrong because the palliatives they claimed they distributed were not distributed properly. If the Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN) wants to distribute electricity bills, they know how to do so. They know houses that owe money. So why can’t they follow the same process to know those who should get money and relief materials, maybe a bag of rice and gallons of cooking oil? If they cannot give them money, they should give them food items. People will find means to add to the ones they get’.

Another participant (a commercial tour driver) lamented that

‘During the lockdown, the rate of travelling was very low. One of the drivers who worked was caught and used 10,000 naira to bail himself and his bus. The palliative they (the government) said they gave people did not circulate. Giving a family man a cup of rice as palliatives cannot serve them as they were at home for many days. Even the blood pressure level of people has risen because people are not happy. They are supposed to share enough palliatives because hunger is the main reason for their unhappiness’.

Commenting on police illegalities, a private firm worker noted that:

‘We have a Police that efficiency is unknown to them, which is the problem we have in Nigeria today. If you have money, you can bribe your way to get anything from the Nigerian Police, which was the same situation that happened during the lockdown. As stringent as they claim it was, I had people who travelled every week to Ibadan to buy clothes and jewelry, not foodstuffs. Many people travelled interstate. There was a ban on interstate movement, as those police officers were compromised. They should stop collecting bribes and enforce the lockdown rules in a more organised and efficient manner’.

The participants who expressed their concerns advised the government on the need for sincerity, provision of sufficient palliatives, vaccination of citizens, monitoring of police officers and punishment for errant officers as effective and practical ideas towards using lockdown for successful management of future pandemics.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the use of lockdown orders to curb the spread of COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria with a focus on Ilorin, public non-compliance, policing shortcomings and the challenges the police personnel faced in the enforcement of the orders. From the result, it was apparent that the public demonstrated an appreciable understanding of the pandemic outbreak and the expediency of the restriction. Demographically, the unemployed population (15%) constituted a reasonable portion of the participants' population. In addition, more than half of the whole population (53.3%) consisted of informal workers: artisans, farmers and traders. Thus, this study captured the feelings of this set of people who were most hit by the lockdown (Amzat et al., 2020) [3]. The commercial tour drivers and police personnel are well experienced in their respective occupations. The majority of them have at least ten years of experience in law enforcement or a driving job. In agreement with previous studies on belief in the pandemic's outbreak in Nigeria, knowledge of happenings, the attitude of the government and practice of the public health safety protocols were foundational to their belief in the existence of COVID-19 in Ilorin city, which support Reuben et al. (2020) [80] findings on knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of people on COVID-19. They believed that infection, subsequent hospitalisation of COVID-19 carriers, and daily situation report from health authorities were reliable signs that the disease truly existed during the lockdown period.

The Nigerian State couldn't achieve total compliance due to the disconnect between the government and citizens. The people's perception of politicians is not positive, and successive governments have failed to provide public benefits to all citizens, diminishing the legitimacy of the state and reducing the power of its police to compel compliance. (Akinlabi, 2020) [11]. Hence, mistrust and insinuation of corruption fueled disobedience in Ilorin City, which was part of the conspiracy theories Amobi et al. (2020) [56] observed in citizens. Despite that, the compliance in Ilorin was high, as 57% of this study's participants were obedient to the curfew order, which is an important measure used to control community transmission of the pandemic (Alfano and Ercolano, 2020) [28]. The pockets of violation of the curfew observed in the city were due to the government's failure to provide economic relief measures that could ensure compliance. In addition to the participants' desire to earn a living, a few of them, despite the variety in the mechanisms used by the police to enforce the curfew, were non-compliant on the socioeconomic basis, which included visitation to family, academic factors and trading of non-essential items.

In the context of procedural justice theory, the procedurally just treatment that boosts trust and cooperation within the police system in a democracy (Wang et al., 2020) [81] such as Nigeria is unsatisfactory. Policing in Nigeria is beset with corrupt and unethical practices rather than full enforcement of extant policing laws. Due to such practices in the police top echelon, trust in and discipline of the subordinates in cases of misconduct are characterized with ethical challenges (Orole et al., 2014) [82]. Hence, the absence of procedural justice within the Nigerian police organization stifled police adherence to tenets of procedural justice in the mainstream society during the lockdown. As such, achieving citizens ‘compliance with the pandemic law was majorly normative and partly instrumental. As there was no strict enforcement of penalties attached to a violation, the compliant study participants (57%) considered obedience to the COVID-19 regulation as a moral obligation for the safety of all. The reports suggest that the police dependence on instrumental compliance did prevent non-compliance. Thus, lending credence to the evidence of this study that the compliance observed in more than half of the participants was normative. Despite the harsh economic realities that trailed the curfew, citizens influenced by the people's KAP about the disease observed the need to be compliant and protect themselves. However, unethical police practices in the form of immoderate use of force, extortion and degrading treatment under the guise of strict enforcement of the pandemic laws appeared to shape citizens' level of compliance. Thus, this study alludes that such unethical practices might have forced some citizens to obey the law by staying at home. The violations were based on socio-economic reasons the study considered unavoidable and in the process of implementing such reasons, some participants interacted with the police unpleasantly. The interaction of participants with the police personnel during the lockdown was more of negative experiences comprising assault, verbal threat, extortion, inhumane treatment, arbitrary use of police power and excessive use of force. This finding substantiates the reports on unacceptable police behaviour in enforcing the stringent curfew (Amnesty International, 2020 [58]; Guardian, 2020 [5]; NHRC, 2020 [44]). In contribution to the global attention on the impact of police misconduct on police legitimacy, especially during an emergency, this study suggests that such unpleasant experiences informed the thinking that the police could easily be compromised. Thus, triggering citizens into non-compliance with the law even if the reasons for non-compliance are not compelling enough. It is a fundamental factor that defeated successful pandemic policing. From the argument above, the police legitimacy was further battered, consequently derailing public trust and confidence needed for effective and result-oriented compliance with and enforcement of the law (Boateng, 2017 [83]; Bolger and Walters 2019 [84]; Cheng, 2020 [61]; Sun et al., 2016 [62]; Wang et al., 2020 [81]). However, it is pertinent to consider citizens' behaviours that fuel the negative interactions with police that subsequently batter police legitimacy. As police officers are members of the public and the public members are police personnel, fundamental issues surrounding police legitimacy, the effectiveness of police response to a crisis and public trust involve both the police and the citizenry.

4.1. Implications for policy, Practice and research

The findings from this study underscore the need to address the issues of defiance and public mistrust concerning government policies, police illegalities and instances of non-compliance with the statewide/nationwide curfew envisaged to limit the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although this research observed a high level of compliance, there is a need for government authorities to look into public mistrust that partly fuels non-compliance. While the findings indicating disagreement with the existence of the pandemic in Ilorin, Nigeria, may appear cynical, they cannot be overlooked. Bordering on corrupt practices and mismanagement of public resources, the public scrutinises and mistrusts government institutions in implementing policies even if such policies appear to serve the citizenry's interest. Hence, the government should take every step to secure citizens' trust in its dealing. The public is willing to support government authorities by ventilating their grievances and suggesting practical ideas to manage future public health emergencies successfully. The approach to containing future pandemics should reflect the country's socio-economic, political, and environmental peculiarities. As well as appreciable investment in the health sector to manage disease outbreaks, result-oriented measures should sufficiently be in place to lessen the socio-economic burdens that result from pandemic-related restrictions before implementing stringent lockdown.

In policing to manage a pandemic, the evidence in this study submits those police illegalities in the form of extortion, immoderate use of force and violence defeated the core purpose of restriction on movement. The instrumental and military-styled mode of enforcement further dampened the police legitimacy and public trust in the police. Also, the personnel appeared to be insufficiently prepared and ill-informed in responding to the pandemic that necessitates implementing new (pandemic) laws. Therefore, the policing approach to managing emergencies should incorporate sufficient equipment/funding for the police. In solving police-public connivance to violate the curfew orders, there should be fair use of technology-based monitoring of checkpoint/border routes in addition to gathering citizens' feedback via communication channels. Furthermore, there should be attention to personnel's welfare and adequate training of police personnel to educate them on adherence to human rights and extant laws that prohibit inhumane treatment: Anti-Torture Act2017.2 This study suggests that increased police oversight be done by an independent body majorly occupied by the citizens. Findings on the investigation of police illegalities from such bodies will enjoy widespread support, thus gaining public trust and legitimacy in the reform process and police. In reforming the police, the authorities must promote a culture of discipline and implement punitive sanctions on erring officers involved in illegalities either in the enforcement of pandemic regulation or general policing activities. With the maintenance of a trustworthy stance, such reform will endear the police to the public and birth/sustain the cordial police-community relation needed for policing and general law enforcement.

5. Conclusion

While earlier studies on procedural justice and pandemic policing examined police behaviour and cited accounts of unpleasant encounters between police personnel and the citizens, the body of literature is yet to include citizens' non-compliance tendency that positions them to police illegalities in enforcing the stringent lockdown. Against that background, this study fills such scholarly vacuity by examining citizens' reasons for violating lockdown orders vis-à-vis pre-existing manners of policing in Nigeria. With a nuanced argument, this study investigated pandemic policing in Ilorin, Nigeria, from two viewpoints; public non-compliance and police conduct. The study participants’ rich insights show that government approaches to the pandemic, particularly the movement restriction were insufficient of socio-economic preparations that could facilitate citizens remaining at home. However, anger, resentment, economic hardship, and mistrust triggered citizens into non-compliance and subsequent use of unconventional means for movement. In the process, they had an unpleasant interaction with police personnel. Despite the avalanche of code of conduct and rules of engagement police officers are obliged to comply with, their interactions with the public was extortive and violent and portend gloomy implications on procedural justice needed for cordial police-public relation and law enforcement, particularly during an emergency. Unethical police practices facilitated congestion and travel along border routes many times thereby substantiating the claims that the police fell short of the expected standard in policing COVID-19. However, the study concluded that lack of procedural justice within the Nigerian police system and in its interaction with the public prior to the lockdown was a precursor to the illegalities that occurred during the lockdown enforcement. Acknowledging the impacts of such illegalities on police-community relations and adopting solutions to the problem will thereby be helpful to law enforcement. Hence, the police authorities should sustain the reform efforts. In doing so, citizens will agree to respect and support the police in discharging their duties in line with the extant laws and best practices.

Declaration of Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Dr. Habeeb Abdulrauf Salihu for his insightful comments and proofreading of this manuscript. In addition, I thank the members of the public and the police officers who voluntarily participated in this study by airing their views concerning the imposed lockdown.

Footnotes

Quarantine Act, CAP Q2, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria (LFN) 2004 is a legislation that provides for the regulation of the imposition of quarantine and the prevention of the outbreak of dangerous infectious diseases into, spread in and the transmission from Nigeria.

Anti-Torture, Act 2017 is a legislation that comprehensively penalises tortuous or cruel acts and degrading or inhumane treatment and punishment and imposes sanction for the commission of such acts.

References

- 1.White M.D., Fradella H.F. Policing a pandemic: stay-at-home orders and what they mean for the police. Am. J. Crim. Justice. 2020;45:702–717. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09538-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stogner J., Miller B.L., McLean K. Police stress, mental health, and resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Crim. Justice. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09548-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amzat J., Aminu K., Kolo V.I., Akinyele A.A., Ogundairo J.A., Danjibo M.C. Coronavirus outbreak in Nigeria: burden and socio-medical response during the first 100 days. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;98:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nigeria Police Force . Lagos: European Union and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2020. Guidelines for Policing during the COVID-19 Emergency.https://www.unodc.org/documents/nigeria//NPF_COVID-19_Guidance_Booklet_Final.pdf 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guardian . 2020. How Police, Military Extort at COVID-19 Checkpoints.https://m.guardian.ng/news/how-police-military-extort-at-covid-19-checkpoints/ September 03 2020. [Google Scholar]