Abstract

Modeling of batch kinetics in minimal synthetic medium was used to characterize Escherichia coli O157:H7 growth, which appeared to be different from the exponential growth expected in minimal synthetic medium and observed for E. coli K-12. The turbidimetric kinetics of 14 of the 15 O157:H7 strains tested (93%) were nonexponential, whereas 25 of the 36 other E. coli strains tested (70%) exhibited exponential kinetics. Moreover, the anomaly was almost corrected when the minimal medium was supplemented with methionine. These observations were confirmed with two reference strains by using plate count monitoring. In mixed cultures, E. coli K-12 had a positive effect on E. coli O157:H7 and corrected its growth anomaly. This demonstrated that commensalism occurred, as the growth curve for E. coli K-12 was not affected. The interaction could be explained by an exchange of methionine, as the effect of E. coli K-12 on E. coli O157:H7 appeared to be similar to the effect of methionine.

Infections due to enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, particularly E. coli O157:H7, are now considered a major public health problem of worldwide importance. Serotype O157:H7 was first identified as a human pathogen during an epidemiological investigation of two outbreaks of hemorrhagic colitis in North America in 1982 (23). Since the early 1980s, this serotype has been implicated in numerous outbreaks of hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome. The sources of infection of humans by E. coli O157:H7 include consumption of undercooked bovine food products and other uncooked foods, water, and direct animal-to-person or person-to-person contact (1, 11, 27).

In the 1990s modeling of E. coli O157:H7 growth has been an active area of research (9, 26, 28). For all food-borne pathogens, the recent developments in modeling have been based on better mathematical descriptions of the growth curves in closed liquid media (batch cultures) (2, 5, 24) and on a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between growth parameters and the physicochemical environment (22, 25).

Application of somewhat theoretical knowledge to predictive analyses of the development of microbial floras has given workers the opportunity to predict the growth of bacteria and fungi in food matrices, and the correspondence between predicted and observed kinetics has been good. Models have been used in simulation software to determine the shelf life of a product (8, 15, 16). However, there are some limitations in so-called predictive microbiology; the structure and heterogeneity of the alimentary matrix, as well as the possible interactions of food-borne pathogens with technological or natural spoilage flora, are poorly taken into account in the models. More generally, batch growth modeling has been widely used for applied objectives, but a more fundamental approach has not been taken. For instance, data concerning the effects of bacterial interactions on bacterial growth, which is a well-established phenomenon in continuous cultures (4, 13, 14, 21), are limited for batch cultures (6, 20).

Modeling of batch kinetics appears to be a promising and underexploited way to examine growth from a physiological point of view. In this study, the kinetics of E. coli O157:H7 growth were examined by using minimal synthetic medium. The choice of this minimal medium, in which all of the components were chemically defined and the only limiting substrate was the carbon source, rather than a complex medium (complex media are usually used as representative of foods), illustrates our orientation towards a physiological approach rather than an applied approach. Different monitoring and statistical tools were used to characterize growth.

Biomass was monitored by turbidimetry; an automated system enabled us to study 15 E. coli O157:H7 strains and 36 other E. coli strains in parallel. A dynamic study of turbidimetric kinetics resulted in characterization of the growing phases of these strains and to quantification of the effect of methionine on growth. Using plate count monitoring of the viable population, we confirmed that growth of E. coli O157:H7 was different from growth of E. coli K-12 and was improved by methionine. This method also allowed us to study a mixed culture of E. coli K-12 and E. coli O157:H7, and the results revealed that there is an interaction between E. coli O157:H7 and E. coli K-12.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Turbidimetric growth curves for pure cultures. (i) Bacterial strains.

A total of 51 E. coli strains were used; these strains included 15 O157:H7 strains and 36 non-O157:H7 strains. The non-O157:H7 strains were chosen on the basis of ecological criteria or virulence factors; we used five reference strains (including one O55:H7 strain), 13 nonverocytotoxic feces isolates, and 18 verocytotoxic SLT1+eae1+ isolates. Strains were checked for the presence of O157 antigen by using the VIDAS System (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and for the presence of H7 antigen by using an in situ hybridization system. Details are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 36 E. coli non-0157:H7 strains and 16 E. coli 0157:H7 strains

| Group | Straina | Description | Pb | Δt (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-0157:H7 | 1 | K-12 reference strain (NC4100) | 0.25 | |

| 2 | K-12 reference strain (CIP 54117) | 0.48 | ||

| 3 | Reference strain (ATCC 15223) | 1 × 10−8 | −27 | |

| 4 | Reference strain (ATCC 25922) | 2 × 10−5 | −31 | |

| 5 | O55:H7 reference strain | 6 × 10−15 | 4 | |

| 6 | Calf feces isolate | 0.19 | ||

| 7 | Calf feces isolate | 0.25 | ||

| 8 | Calf feces isolate | 0.53 | ||

| 9 | K99+ calf feces isolate | 0.48 | ||

| 10 | Human feces isolate | 1.00 | ||

| 11 | Human feces isolate | 1 × 10−13 | 3 | |

| 12 | Human feces isolate | 0.06 | ||

| 13 | Human feces isolate | 1.00 | ||

| 14 | Human feces isolate | 1.00 | ||

| 15 | Human feces isolate | 0.36 | ||

| 16 | Human feces isolate | 1 × 10−15 | 8 | |

| 17 | Human feces isolate | 2 × 10−37 | 0 | |

| 18 | Human feces isolate | 0.97 | ||

| 19 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 0.40 | ||

| 20 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 2 × 10−6 | 5 | |

| 21 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 0.20 | ||

| 22 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 0.63 | ||

| 23 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 0.18 | ||

| 24 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 0.16 | ||

| 25 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 1 × 10−4 | 8 | |

| 26 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 0.82 | ||

| 27 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 6 × 10−8 | 9 | |

| 28 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 0.99 | ||

| 29 | Calf feces isolate, SLT1+ eae+ | 1 × 10−7 | 6 | |

| 30 | O157 non-H7 calf feces isolate | 0.99 | ||

| 31 | O103:H2 human feces isolate | 1.00 | ||

| 32 | O103:H2 human feces isolate | 0.43 | ||

| 33 | O103:H2 human feces isolate | 0.44 | ||

| 34 | O157 non-H7 human feces isolate | 0.34 | ||

| 35 | O157 non-H7 cow’s milk isolate | 1 × 10−4 | 10 | |

| 36 | Human feces isolate, eae+ SLT1+ | 0.34 | ||

| O157:H7 | 37 | Reference strain (ATCC 35150) | 1 × 10−8 | 13 |

| 38 | Reference strain (ATCC 43888) | 3 × 10−8 | 86 | |

| 39 | Reference strain (ATCC 43895) | 8 × 10−2 | 14 | |

| 40 | Reference strain (ATCC 43890) | 4 × 10−12 | 10 | |

| 41 | Reference strain (ATCC 43894) | 3 × 10−3 | 16 | |

| 42 | Clinical isolate | 4 × 10−8 | 13 | |

| 43 | Beef isolate | 2 × 10−10 | 18 | |

| 44 | Clinical isolate | 1 × 10−2 | 18 | |

| 45 | Food isolate | 8 × 10−3 | 22 | |

| 46 | Food isolate | 3 × 10−8 | 17 | |

| 47 | Clinical isolate | 5 × 10−2 | 19 | |

| 48 | Human feces isolate | 3 × 10−3 | 7 | |

| 49 | Human feces isolate | 2 × 10−4 | 17 | |

| 50 | Human feces isolate | 3 × 10−16 | 10 | |

| 51 | Minced beef isolate | 0.72 |

Strains 6 to 9 were obtained from J. L. Martel (Centre National d’Etudes Vétérinaires et Alimentaires, Lyons, France); strains 10 to 18 and 36 were obtained from M. Chomarat (Hôpital Lyon Sud, Lyons, France); strains 19 to 30 were obtained from A. Milon (Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire, Toulouse, France); strains 31 to 33 were obtained from P. Mariani-Kurkdjian (Hopital Robert Debré, Paris, France); strains 34, 35, 50, and 51 were obtained from K. Grif (Institute of Hygiene, Innsbruck, Austria); strains 42 to 47 were obtained from R. Johnson (bioMérieux, St. Louis, Mo.); and strains 48 and 49 were obtained from J. Freney (Hôpital Edouard Herriot, Lyons, France).

Statistical values were based on turbidimetric kinetics data. P is the P value from a t test for the slope of μ versus time; if P was <0.05, the growth rate in minimal synthetic medium was significantly increasing (boldface values).

Δt is the difference between the length of the growing phase in minimal medium and the length of the growing phase in medium supplemented with methionine expressed as a percentage. The effect was considered positive if Δt was >5% (boldface values).

All bacterial stock cultures were maintained at −196°C in brain heart infusion broth (bioMérieux) containing 10% glycerol.

(ii) Minimal synthetic medium.

The medium used in the experiments was the minimal medium designed by Neidhardt et al. (18) supplemented with thiamine. It contained (per liter) 8.372 g of MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid), 2.922 g of NaCl, 0.71668 g of Tricine, 0.5082 g of NH4Cl, 0.23 g of K2HPO4 · 3H2O, 0.11 g of C6H12O6 · H2O, 0.107348 g of MgCl2 · 6H2O, 0.0481 g of K2SO4, 0.01 g of thiamine, 7.351 mg of CaCl2 · 2H2O, 2.78 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O, 0.0247 mg of H3BO3, 0.0158 mg of MnCl2 · 4H2O, 0.0071 mg of CoCl2 · 6H2O, 0.0037 mg of (NH4)6MO7O24 · 4H2O, 0.0029 mg of ZnSO4 · 7 H2O, and 0.0016 mg of CuSO4. This medium was designated Neidhardt medium.

(iii) Characterizing the growth phase in minimal synthetic medium.

Prior to an experiment, each bacterial strain was grown twice on Columbia sheep blood agar at 35°C for 24 h in order to obtain cells in the stationary phase of growth. Suspensions obtained from the resulting precultures were standardized with a nephelometer (model ATB 1550; bioMérieux) to a no. 1 MacFarland standard and then diluted 10−2.

An MS2 Research system (Abbot Laboratories, Dallas, Tex.) was used to monitor growth continuously. This automated system can process 16 11-growth-chamber cartridges. Each growth chamber contained 1 ml of Neidhardt medium inoculated with 100 μl of a bacterial suspension. The cartridges were inserted into the system and maintained for 24 h at 37°C; there was constant agitation between measurements. Transmission was measured at 5-min intervals, and evolution of absorbance was calculated from the resulting data (10). For graphical representations, growth curves were smoothed by using the ExponentialSmoothing procedure of Mathematica (Wolfram Research, Inc.).

To determine an approximate instantaneous growth rate, the specific absorbance rate (μ) was calculated with the following formula:

|

1 |

where μ (tn) is the specific absorbance rate (per hour) at time tn and yn is the measured absorbance at tn.

To check the hypothesis that the instantaneous μ does not increase at the end of the so-called exponential phase, a unilateral t test was performed. This test was used to determine whether the slope of the linear regression (μ versus time) was zero or significantly positive between a technical threshold (when the measured absorbance reached 0.005) and deceleration (obviously detected by a swift decrease in μ) (i.e., in the last phases of growth).

(iv) Quantifying the effect of methionine.

To quantify the effect of methionine for each strain, we compared two growth curves (one determined with Neidhardt medium and one determined with Neidhardt medium supplemented with 100 mg of methionine per liter) resulting from identical inocula. The difference between the time when the growing phase ended in the minimal medium and the time when the growing phase ended in the supplemented medium was then determined and expressed as a percentage of the length of the growing phase in minimal medium.

Plate count growth curves for pure and mixed cultures. (i) Bacterial strains.

Two reference strains, E. coli K-12 strain NC 4100 and E. coli O157:H7 strain ATCC 33150, were used in this study. Cultures were stored at −196°C in brain heart infusion (bioMérieux) supplemented with 10% glycerol.

(ii) Inoculum preparation.

Prior to each experiment, the bacterial strains were grown on Columbia sheep blood agar (bioMérieux) at 35°C for 24 h and then in Neidhardt medium at 37°C with turbidimetric growth monitoring (the growth conditions used are described above). The resulting precultures were stopped either in the early exponential phase (i.e., when the absorbance had increased 0.01) or in the stationary phase (4 ± 1 h after the end of growth) and then used to inoculate the experimental cultures. Thus, the inocula used for the main cultures could be in two different initial physiological states; they contained either growing cells (preculture stopped in the early exponential phase) or resting cells (preculture stopped in the stationary phase).

(iii) Growth conditions.

Each 250-ml Erlenmeyer flask contained 200 ml of Neidhardt medium. Spinal needles (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) in the caps of the flasks allowed us to inoculate the medium and retrieve samples under sterile conditions. The flasks were incubated in thermostat-controlled water baths (the temperature was regulated at 37 ± 0.1°C), and the medium was aerated by using a magnetic stirrer.

(iv) Growth monitoring.

At each sampling time (every 30 min for each culture), the number of viable cells was determined by plating two 0.1-ml portions of appropriate dilutions of the sample onto MacConkey agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England) containing sorbitol.

We checked whether this medium could be used to distinguish between the two strains since only E. coli K-12 ferments sorbitol, and we found that it does not inhibit growth. The plate counts on MacConkey Agar (Oxoid) containing sorbitol were not different from the plate counts on Columbia sheep blood agar (bioMérieux).

(v) Experimental design.

We performed an experiment to confirm previously described results. Two cultures were grown in parallel, one in minimal medium and the other in minimal medium supplemented with 100 mg of methionine per liter. Each culture was inoculated with 0.5 ml of a preculture of E. coli O157:H7 in the stationary phase.

For the main experiments we carried out three parallel cultures, a pure culture of E. coli K-12, a pure culture of E. coli O157:H7, and a mixed culture. We performed eight main experiments, including two replicates for each of the four combinations of possible initial physiological states for E. coli K-12 and E. coli O157:H7.

Three flasks were used for each main experiment. The first flask was inoculated with x milliliters an E. coli K-12 preculture, the second flask was inoculated with y milliliters of an E. coli O157:H7 preculture, and the third flask was inoculated with x milliliters of an E. coli K-12 preculture and y milliliters of an E. coli O157:H7 preculture. The population sizes in the precultures were determined, and x and y were chosen so that the initial population contained 104 to 105 CFU/ml; x and y were between 0.5 and 10. Each mixed-culture experiment was carried out with two parallel control pure cultures.

(vi) Growth models.

The data obtained were then analyzed. The final data obtained (in the stationary phase) were not included so that only growth was examined.

Two growth models were used in this study. The first model (which included a lag phase and an exponential phase) was a three-parameter model:

|

2 |

where x is the number of CFU per milliliter, x0 is the initial number of CFU per milliliter, t is the time (hours), lag is the lag time (hours), and μ is the growth rate (per hour).

The lag phase was the period during which the growth rate was zero; the transition to the exponential phase was then supposed to be instantaneous. There are different ways to describe acceleration more precisely (2, 29), but our simple model was sufficient when the monitoring period was 30 min long. Moreover, it had the advantage that it allowed testing of the nullity of the lag time by comparing equation 2 and a two-parameter model without a lag phase:

|

3 |

An F test based on the likelihood ratio (3) confirmed for both strains that equation 3 was sufficient for a growing-cell inoculum but that equation 2 was necessary for a resting-cells inoculum. It has been known since the 1950s that the lag time is zero if the inoculum is obtained in the exponential phase (17).

Eventually, the hypothesis that a strain in a particular experiment has the same growth parameters in a pure culture and in a mixed culture (or in minimal medium and in medium supplemented with methionine) was tested by performing an F test based on the likelihood ratio (3). A model common to the two growth curves obtained in one experiment was fitted. The equality of μ and lag was tested by comparing a full model (μp and lagp in pure culture; μm and lagm in a mixed culture or a culture supplemented with methionine) to a partial model (with the constraints μp = μm and lagp = lagm). We assumed that x0 for the pure culture and x0 for the mixed culture were the same (the methods used resulted in sufficient repeatability of the initial concentration of one strain). These analyses were performed by using Mathematica (Wolfram Research, Inc.), and the risk factor α used for the F tests was 5%.

(vii) Evaluation of fit.

For each model, the quality of the fit was visually evaluated by examining superimposed data sets and theoretical growth curves. The autocorrelation and the heteroscedasticity in the distribution of the residual values were examined on the graphs of residual values versus time.

RESULTS

Characterization of E. coli turbidimetric kinetics.

We investigated the growth of 15 O157:H7 strains by monitoring the changes in absorbance. The growth did not appear to be exponential. μ, which theoretically is supposed to be constant according to the exponential-phase hypothesis, obviously varied during growth. The detection limit of the method did not allow us to detect an obvious decrease in μ at the beginning of growth, but an increase in μ at the end of growth was clearly observed (Fig. 1). A t test was performed for the slope of μ versus time. For 94% of the strains tested (14 of 15 strains), this test indicated that there was a significant increase in μ at the end of growth (Table 1).

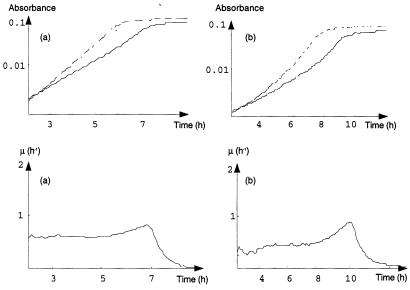

FIG. 1.

E. coli O157:H7 nonexponential growing phases, showing the effect of methionine. (a) Strain 40. (b) Strain 42. (Upper graphs) The solid line is the smoothed turbidimetric growth curve obtained with minimal synthetic medium; the dotted line is the smoothed turbidimetric growth curve obtained with medium supplemented with methionine. (Lower graphs) μ, calculated from smoothed data.

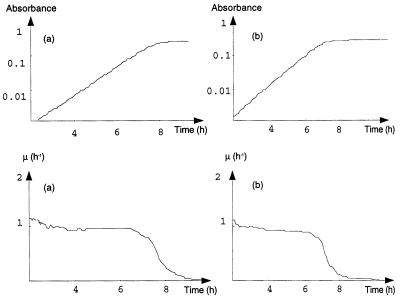

The observed variations in the instantaneous μ for most O157:H7 strains were all the more unexpected since such variations were not observed for most non-O157:H7 strains. Of 36 non-O157:H7 strains, 25 (70%) exhibited exponential growth until a swift transition to the stationary phase characterized by a sharp decrease in μ (Fig. 2). For these 25 strains, μ did not significantly increase at the end of growth (Table 1). The kinetics of the 11 other strains were similar to those of E. coli O157:H7.

FIG. 2.

E. coli non-O157:H7 exponential growing phases. (a) Strain 13. (b) Strain 17. (Upper graphs) Smoothed turbidimetric growth curves in minimal synthetic medium. (Lower graphs) μ, calculated from smoothed data.

Since such an anomaly had never been detected in complex medium, different modifications of the minimal synthetic medium were examined. In particular, the medium was supplemented with different mixtures of the 18 essential amino acids. We found that methionine had a positive effect on the growth of E. coli O157:H7 strain ATCC 33150 (data not shown).

For each strain that exhibited nonexponential growth, the effect of methionine was quantified by determining the difference between the length of the growing phase in minimal medium and the length of the growing phase in medium supplemented with methionine expressed as a percentage. Table 1 clearly shows that the effect of methionine was greater for serotype O157:H7 strains than for other E. coli strains. Both a significant growth anomaly (P < 0.05) and a methionine effect greater than 5% were observed for 93% (14 of 15) of the O157:H7 strains, 22% (4 of 18) of the verocytotoxic non-O157:H7 strains, 8% (1 of 13) of the nonverocytotoxic feces isolates, and none of the reference strains.

Modeling of E. coli plate count kinetics.

Using plate count monitoring, we confirmed the results obtained with turbidimetric monitoring and investigated mixed cultures of E. coli K-12 and E. coli O157:H7.

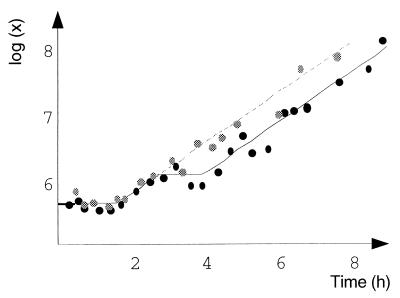

We performed an experiment to determine the effect of methionine with plate count monitoring. The growth of E. coli O157:H7 in minimal medium supplemented with methionine appeared to be faster than the growth in minimal medium and closer to the expected exponential growth (Fig. 3). An F test comparison of a full model (μp and lagp in pure culture; and μm and lagm with methionine) and a partial model (with the constraints μp = μm and lagm) led us to reject the hypothesis that μp was equal to μm and lagp was equal to lagm (P = 7 × 10−5).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of growth curves for E. coli O157:H7 strain ATCC 33150 obtained with and without methionine (resting cell inoculum). Solid circles, minimal medium; shaded circles, medium supplemented with methionine; lines, fitted models.

Another model was fitted to the same pair of growth curves by using the following assumptions: the inocula were equal (x0p = x0m) and the lag times were equal (lagm = lagm); exponential growth occurred with methionine (at constant growth rate μm); and triphasic growth occurred in pure cultures (first and last phases at growth rate μm and no growth in the intermediary phase). This model fit the data well (Fig. 3) and was statistically the best model tested.

The eight main experiments were carried out to characterize the growth of the two strains separately and together. In order to detect any interaction between the two populations in mixed cultures, the experiment was designed so that we could rigorously compare the growth of each strain in pure culture and in a mixed culture by examining the growth parameters.

Equations 2 and 3 were fitted to the eight growth curves for E. coli K-12 pure cultures. In all cases, the graphs obtained (residues and growth curves) proved that the exponential models (with or without a lag phase) were relevant. Then the growth curves for pure cultures were compared to the growth curves for mixed cultures. In each main experiment, the two curves obtained for E. coli K-12 could obviously be superimposed. There was not a significant difference between growth parameters for any pair of growth curves (Table 2). Thus, the growth parameters of E. coli K-12 were not significantly modified by the presence of E. coli O157:H7 in the same medium, whatever the physiological states of the two inocula (Fig. 4).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of growth curves for pure and mixed cultures

| Type of cells |

E. coli K-12

|

E. coli O157:H7

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | Pb | n | P | |

| Growing | 28 | 0.05 | 25 | 2 × 10−4 |

| 19 | 0.52 | 32 | 3 × 10−3 | |

| 26 | 0.53 | 22 | 0.19 | |

| 24 | 0.61 | 28 | 0.86 | |

| Resting | 29 | 0.45 | 25 | 1 × 10−12 |

| 24 | 0.50 | 29 | 6 × 10−7 | |

| 28 | 0.39 | 25 | 9 × 10−3 | |

| 22 | 0.85 | 31 | 0.04 | |

Each data set is composed of the viable cell count in pure culture and the viable cell count for the same strain in a mixed culture in the same experiment, and n is the number of experimental points in the data set.

P is the P value from an F test for the comparison of a full model and a partial model. If P was <0.05, there was a significant difference between the pure culture and the mixed culture.

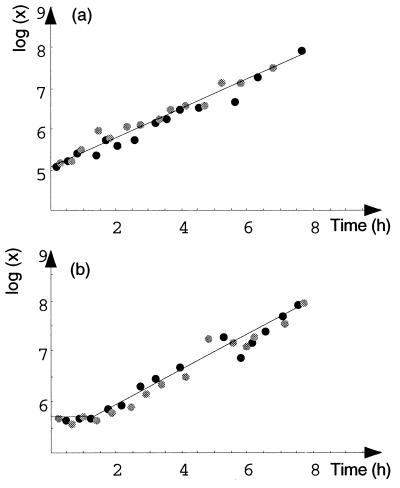

FIG. 4.

Comparison of mixed and pure cultures of E. coli K-12 strain NC4100. (a) Growing cell inoculum. (b) Resting cell inoculum. Solid circles, pure culture; shaded circles, mixed culture; lines, fitted exponential model with a lag phase (b) or without a lag phase (a).

Equations 2 and 3 were fitted to the eight growth curves for E. coli O157:H7 pure cultures. An obvious autocorrelation of residues was detected, which meant that the exponential-growth hypothesis was not adapted to the data obtained. When pure and mixed cultures were compared, it appeared in each experiment that the two curves for E. coli O157:H7 could not be superimposed. For six of the eight experiments (all combinations of initial physiological states except the growing cell-growing cell combination), there were significant differences between the growth parameters for pairs of pure-culture–mixed-culture growth curves for E. coli O157:H7 (Table 2). Another model was fitted to these pairs by using the following assumptions: the inocula were the same (x0p = x0m) and the lag times were the same (lagp = lagm) exponential growth occurred in mixed cultures (at constant growth rate μm); and biphasic growth occurred in pure cultures (first at the growth rate of the mixed culture [μp1 = μm] and then at a lower growth rate, μp2).

This model fit the data well (Fig. 5) and was statistically the best model tested. The second growth phase could have been divided into a slower growth phase followed by a faster growth phase, but our data were not sufficient to obtain a satisfactory fit.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of mixed and pure cultures of E. coli O157:H7 strain ATCC 33150. (a) Growing cell inoculum. (b) Resting cell inoculum. Solid circles, pure culture; shaded circles, mixed culture; lines, fitted nonexponential model with a lag phase (b) or without a lag phase (a).

DISCUSSION

In pure cultures in minimal synthetic medium, E. coli O157:H7 growth curves were obviously not exponential. To our knowledge, the triphasic kinetics described here has not been described previously and cannot a priori be explained by a simple phenomenon. Moreover, coculture with E. coli K-12 and adding methionine resulted in partially or totally normal growth. It could be supposed both treatments had the same effect, namely, reestablishing what occurs at the beginning and end of growth. Thus, E. coli K-12 could release methionine into the medium, and the slow intermediate phase in pure cultures in minimal synthetic medium could be explained by a lack of methionine. Nonetheless, none of these biological hypotheses has been proven. Essentially, the aim of this study was to demonstrate the existence of this unexpected phenomenon. A complete biological interpretation would require complementary tools.

Last, the double phenotype (growth anomaly and correction by adding methionine) was detected for most O157:H7 strains. An O157:H7 strain (strain 5), which was found to be phylogenetically linked to serotype O157:H7 by Feng et al. (12), appeared to behave similarly. Thus, it could be supposed that the physiological anomaly described here characterizes the O55:H7-O157:H7 phylogenetic branch.

In addition to the results concerning E. coli O157:H7 specifically, this study allowed us to develop tools for modeling the different life phases in a bacterial culture (7) by using two monitoring methods (turbidimetry and plate counting) and different statistical procedures. Our use of a minimal synthetic medium resulted in some theoretical simplifications.

One of the main advantages of using a minimal synthetic medium is that there is theoretically only one deceleration phase, corresponding to the disappearance of the limiting substrate (which in this case was the carbon source, glucose). The deceleration phase was actually characterized by a sharp decrease in μ. For the same reasons, the exponential model, which provides approximations in most complex media, should theoretically be suitable for describing bacterial growth in minimal synthetic medium. Actually, this hypothesis was confirmed by the statistical results obtained for plate count growth curves for one reference E. coli strain and by the results of a dynamic study of the turbidimetric growth curves obtained for 25 E. coli strains. However, growth of E. coli O157:H7 was not consistent with the prototypical exponential model for minimal synthetic medium. New methods to investigate the nonexponential growth observed were developed; for the most part these methods were based on calculating an instantaneous μ (for a period of 10 min) instead of estimating a growth rate based on the whole growth curve. This approach was possible because we used a sensitive and precise apparatus to monitor growth by turbidimetry with a short monitoring period. Nonexponential growth may not be rare and might be observed with other species. The lack of adequate monitoring and modeling processes could explain why it is not detected or is ignored.

Using a minimal synthetic medium simplified detection of interactions; as growth was supposed to be limited only by the limiting substrate, there was no competition for the substrate as long as the concentration of the substrate was not limiting (i.e., in the whole exponential phase). The plate count method was adequate for monitoring two different populations in a mixed culture, as long as there were differential or selective media. Plate count results were studied by using a statistical method based on comparisons of growth curves. Assuming that there is no competition for the substrate during the growth phase, the growth curves for one strain under certain conditions should be superimposable for pure and mixed cultures if there is no other interaction. The assumptions mentioned above and the use of the F test allowed us to detect any significant effect of one strain on the growth of the other and then to characterize the interaction. The interaction between E. coli K-12 and E. coli O157:H7 detected, in which one strain had a positive effect on the growth of the other without being modified itself, was classified as commensalism as described by Odum (19). A similar statistical approach (but with organisms grown in a complex medium) was also used very recently by Pin and Baranyi (20).

The unexpected growth of E. coli O157:H7 showed that the batch growth modeling approach is a useful tool for characterizing bacterial strains physiologically. Conversely, taking into account physiological information (such as interactions with other bacteria, the state of the inoculum, abnormal growth characteristics, etc.) could enrich the bacterial growth modeling process, especially in the area of predictive microbiology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Catherine Pichat for technical assistance and Véronique Guérin and Frédéric Laurent for helpful discussions. All of the workers who provided E. coli strains are gratefully acknowledged.

We thank bioMerieux Inc. for supporting this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong G L, Hollingsworth J, Morris J G. Emerging food-borne pathogens: Escherichia coli O157:H7 as a model of entry of a new pathogen into the food supply of the developed world. Epidemiol Rev. 1996;18:29–51. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baranyi J, Roberts T A. A dynamic approach to predicting bacterial growth in food. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;23:277–294. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates D M, Watts D G. Nonlinear regression analysis & its applications. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazin M J. Mixed culture kinetics. In: Bushell M E, Slater J H, editors. Mixed culture fermentations. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bratchell N, McClure P J, Kelly T M, Roberts T A. Predicting microbial growth: graphical methods for comparing models. Int J Food Microbiol. 1990;11:279–288. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(90)90021-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breidt F, Fleming H P. Modeling of the competitive growth of Listeria monocytogenes and Lactococcus lactis in vegetable broth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3159–3165. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3159-3165.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchanan R E. Life phases in a bacterial culture. J Infect Dis. 1918;23:109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan R L. Using spreadsheet software for predictive microbiology applications. J Food Safety. 1991;11:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan R L, Bagi L K, Goins R V, Philips J G. Response surface model for the growth of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Food Microbiol. 1993;10:303–315. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corman A, Carret G, Pave A, Flandrois J P, Couix C. Bacterial growth measurement using an automated system: mathematical modelling and analysis of growth kinetics. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1986;137B:133–143. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2609(86)80102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyle M P. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its significance in foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;12:289–302. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90143-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng P, Lampel K A, Karch H, Whittam T S. Genotypic and phenotypic changes in the emergence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1750–1753. doi: 10.1086/517438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredrickson A G. Behaviour of mixed cultures of microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1977;31:63–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottschal J C. Different types of continuous culture in ecological studies. Methods Microbiol. 1990;22:87–124. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClure P J, Blackburn W, Cole M B, Curtis P S, Jones J E, Legan J D, Ogden I D, Peck M W, Roberts T A, Sutherland J P, Walkers S J. Modelling the growth, survival and death of microorganisms in foods: the UK food micromodel approach. Food Microbiol. 1994;23:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMeekin T, Ross T. Modeling applications. J Food Prot. 1996;1(Suppl.):37–42. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.13.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monod J. Recherches sur la croissance des cultures bactériennes. Paris, France: Hermann; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neidhardt F C, Bloch P L, Smith D F. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odum E P. Fundamentals of ecology. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pin C, Baranyi J. Predictive models as means to quantify the interactions of spoilage organisms. Int J Food Microbiol. 1998;41:59–72. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(98)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell E O. Criteria for the growth of contaminants and mutants in continuous culture. J Gen Microbiol. 1958;18:259–268. doi: 10.1099/00221287-18-1-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ratkovsky D A, Olley J, McMeekin T A, Ball A. Relationship between temperature and growth rate of bacterial cultures. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:1–5. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.1-5.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riley L W, Remis R S, Helgerson S D. Hemorrhagic colitis associated with a rare Escherichia coli phenotype. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:681–685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303243081203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross T. Indices for performance evaluation of predictive models in food microbiology. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:501–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosso L, Lobry J R, Flandrois J P. An unexpected correlation between cardinal temperatures of microbial growth highlighted by a new model. J Theor Biol. 1993;162:447–463. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1993.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salter M A, Ross T, McMeekin T A. Applicability of a model for non-pathogenic Escherichia coli for predicting the growth of pathogenic Escherichia coli. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:357–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slutsker L, Ries A A, Greene K D, Wells J G, Hutwagner L, Griffin P M. Escherichia coli O157:H7 diarrhea in the United States: clinical and epidemiologic features. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:505–513. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-7-199704010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutherland J P, Bayliss A J, Braxton D S. Predictive modelling of growth of Escherichia coli O157:H7: the effects of temperature, pH and sodium chloride. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995;25:29–49. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)00082-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zwietering M H, Rombouts F M, Van’t Riet K. Comparison of definitions of the lag phase and the exponential phase in bacterial growth. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]