Abstract

The values and roles of biodiversity at the grassroots level get little attention and are usually ignored, despite mounting evidence that effective relationships between biodiversity and indigenous people are critical to both ecological integrity and rural survival. ‘Jhumscape’ (the landscape of shifting cultivation) can contribute a great deal to enriching agrobiodiversity and ensuring food security, but this system of cultivation has been mostly neglected. The objective of the present study was twofold: (1) to quantify the agrobiodiversity of a jhumscape in the Eastern Himalayas, especially its contribution to food and nutritional security, and (2) to examine the jhum practices in view of the agroecological principles recently proposed by the Food and Agricultural Organization. Applying mixed-method research and using primary data from 97 households representing eleven villages, transect walks, and interviews of key informants, the plant diversity maintained in a traditional jhum system by the indigenous people was seen to comprise of 37 crops including many landraces and four non-descript breeds of livestock. The food basket was supplemented with wild edible plants collected from fringes of forests and fallow lands that are a part of the jhumscape. Diversity in food groups and the share of expenditure on food in the total budget indicates that the indigenous people are secure in terms of food and nutrition. Jhum agroecological practices such as zero tillage and organic mixed-crops farming based on traditional ecological knowledge helps to maintain a high level of agrobiodiversity. Using biodiversity more effectively for agroecological transition does not mean merely returning to traditional practices but requires a deeper understanding of how agrobiodiversity contributes to better nutrition, greater food security, and sustainability. Although some principles and local practices related to jhum are applicable globally, others may be specific to the region and the culture.

Keywords: Food security, Indigenous farming communities, Jhum agroecological practices, Shifting cultivation, Sustainability

Introduction

Biodiversity is on the verge of extinction on a global scale (WWF 2020), and the threat extends to agrobiodiversity, which encompasses processes such as pollination, nutrient cycling, pest control, and other ecological processes that sustain production systems as well as domesticated and undomesticated plants, animals, and microbes that contribute to food and agriculture (Hunter et al. 2017). The elimination of pollinators and other organisms that support food and agriculture and overdependence on a few species, variations, and breeds endanger the sustainability of our food system and have adverse effects on human and environmental health (Willett et al. 2019). Micronutrient deficiencies are common in low-diversity diets, increasing the risk of malnutrition (Lachatet al. 2018; Afshin et al. 2019). Monocultures and other simpler production systems are more susceptible to pest and disease outbreaks (Altieri and Nicholls 2018) and also suffer from poor soil quality (McDaniel et al. 2014; Beillouin et al. 2019), variable yields (Raseduzzaman and Jensen 2017; Beillouin et al. 2019; Stomph et al. 2020), and greater chances of losses of harvest (Renard and Tilman 2019).

Although large-scale and intensive farming has increased productivity, at the same time such farming has also led to significant environmental degradation in recent decades owing to its expansion into natural areas, increased use of external inputs, and other types of intensive use (IPBES, 2019). Meanwhile, agroecology continues to thrive in small-scale family farming, which in worldwide, is estimated to occupy about 30% of all cultivated area and yet accounts for about half of all food consumed by people (Graeub et al. 2016; Lowder et al. 2019). Governments, development organizations, scientists, and farmers are all interested in agroecology’s potential to become a ‘third way’ model that may handle trade-offs between food security and other ecosystem services (e.g., HLPE 2019; WWF 2020). Agroecology, which is increasingly recognized for its ability to bring about dramatic changes required to accomplish the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is likely to benefit from holistic and people-centred methods that embrace a long-term perspective (FAO 2018; HLPE 2019). More than half of the 17 SDGs are directly addressed by this agricultural strategy, which has a beneficial impact on all of them. This strategy also addresses ethical concerns as a part of the larger effort to dismantle power structures that have developed around scientific knowledge and its monopoly on the production of ‘truth’ (Fricker 2007; Kindon et al. 2007; Bacon et al. 2014; Levidow et al. 2014). By territorializing food production and consumption, agroecology offers a chance to rebuild a post-COVID-19 agriculture capable of preventing future widespread food supply shocks (Altieri and Nicholls 2020a). Agroecology can also be thought of as a set of practices that allows a more sustainable agriculture; a movement that brings together various actors with the goal of developing sustainable agriculture; a scientific discipline that studies how agroecosystems function (Wezel et al. 2009)—or all of these aspects put together.

The phrase ‘agroecological practices’ was coined (Wezel et al. 2009) during the growth of agroecology in the 1980s. Cover crops, green manure, intercropping, agroforestry, biological control, resources and biodiversity conservation, and integration of livestock husbandry and farming are all examples of agroecological practices (Wezel et al. 2014). Nonetheless, the qualities that distinguish them as agroecological practices are yet to be defined. However, more complex agroecological systems that included multiple components (e.g., crop diversification, mixed crop-livestock systems, and farmer-to-farmer networks) probably strengthened food security and nutritional security of households in low- and middle-income countries (Kerr et al. 2021); whereas use of biodiversity and environmental services in agricultural production are at the heart of agroecology. Indeed, the urgency to reconcile food security and biodiversity conservation is greater than ever before, given the increasing pressures from population growth, natural disasters, climate change (Almond et al. 2020), and now the COVID-19 pandemic.

In fact, agroecology is not a brand-new concept. Since the 1920s, it has been documented in scientific literature and has found expression in family farming techniques, grassroots social movements for sustainability, and state policies in a variety of nations throughout the world and has recently gained the attention of international and UN organizations (FAO 2018). Traditional farming takes many different forms globally, but all follow the principle of ecological conservation (Gomiero 2018). Traditional farming meets about 90% of the livelihood and economic needs of tribal people (Pradhan et al. 2018) and is characterized by minimum mechanization, temporary or permanent organic cover, crop rotations, and mixed cropping (Bhan and Behera 2014). Mechanical disturbance to soil is also minimized by practising low tillage or zero tillage and multiple cropping, and organic cover is obtained through a cover crop, organic composting, livestock-integrated farming, pasture cover, or grazing. Many traditional farming practices are performed by Indian farmers to modify modern agriculture for the conservation of the environment, culture, and genetic resources (Patel et al. 2020; Bisht et al. 2021). Traditional farming practices are founded on centuries of indigenous knowledge and experience and continue to be popular even now. These practices include agroforestry, intercropping, crop rotation, cover cropping, traditional organic composting, integrated crop–animal farming, and shifting cultivation or swidden agriculture (Giri et al. 2020; Hamadani et al. 2021).

A form of traditional agroforestry system, shifting cultivation is spread over 280 mha globally (Heinimann et al. 2017). Around 200 million people in Asia rely on this forest-based agriculture (Cairns 2017; Karki 2017). The system –which involves clearing forest vegetation from a selected plot by slashing and burning, cultivating the land for one or two years, and then abandoning the land as fallow to restore soil fertility through natural vegetation regeneration—is used as the primary method of farming by indigenous people in various parts of the tropical uplands (Tripathi et al. 2017). Slashing and burning has remained the most straight forward method of preparing land for cultivation, not only for sanitizing the soil and reducing weeds and soil pathogens but also for releasing the nutrients trapped within the biomass by turning it into ash, thereby making them more easily available (Juo and Manu 1996; Wapongnungsang and Tripathi 2018). However, the use of fire to burn the plant debris that remains after forest clearing is the aspect of shifting cultivation that draws the greatest criticism (Nigh and Diemont 2013)—which is why shifting cultivation is also often blamed for deforestation and biodiversity loss (Tinker et al. 1996; Sodhi et al. 2010) and is being abandoned and replaced with settled cultivation, mainly of cash crops and plantations of rubber and oil palm (Van Vliet et al. 2012).

It is for these reasons that the present study seeks to elucidate the dynamics of agrobiodiversity and agroecological practices as they play out in one indigenous farming system practised in north-eastern India in the Eastern Himalayas.

Methods

Study area

Arunachal Pradesh, one of the seven north-eastern states of India, is one of the ecological hotspots and falls in the Himalayas zone of the 36 biodiversity hotspots in the world (FSI 2019; Kobayashi et al. 2019). Agriculture and forest resources are the main sources of livelihood of those people in Arunachal Pradesh who practise conventional farming in the valleys and ‘jhum’ (the local term for shifting cultivation) on steep slopes, with fallow periods that extend to 10–11 years. Jhum cultivation covers over 52% of Arunachal Pradesh’s gross cultivated area (NRSC 2019). In the hilly parts of Arunachal Pradesh, the challenging topography, uneven terrain, constant rains, and harsh climatic conditions drove these indigenous groups to the age-old practice of jhuming.

The present study was carried out during 2016/17 in Upper Subansiri district, a mountainous region of the state of Arunachal Pradesh in India. The predominant ethnic groups in the district are Tagins, Galos, and Nyishi. The precise location of the study area and the most relevant details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Upper Subansiri district, Arunachal Pradesh, north-eastern India: the study area

| Location | Total land area (km²)a | Forest cover (% of total area)b | Population density (km²)a | Area under jhum (km²)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current shifting cultivation | Fallow | ||||

| 27° 45′ to 28° 13′ N, 93° 13′ to 94° 36′ E | 7032 | 79.08 | 12 | 47.39 | 3.53 |

Data collection

The present study involved 97 tribal households from 11 village clusters from four communities and rural development blocks (a block is an administrative unit), namely Daporijo, Dumporijo, Maro, and Puchi Geku (Fig. 1). The blocks were selected based on the information provided by the District Forest Officer and by the head of the Krishi Vigyan Kendra (Agriculture Science Centre) of the district, the basis for selection being the extent or intensity of jhum and the highest density of households practising jhum. The villages for data collection were identified with the help of block-level officials and also taking into account the accessibility. The eleven villages, their respective blocks, and the number of households selected from each were as follows: Reddi Old, Beyar, and Aya Marde from Dumporijo block (25 households); Dulan, Lebar, and Batok from Daporijo block (23 households); MaroNuk and Maro Ricchi from Maro block (24 households); and Baja, Babla, and Gigi from Puchi Geku block (25). For both sparse and clustered populations, conventional sampling designs such as simple random sampling have their limitations and therefore we chose adaptive cluster sampling to maximize survey efficiency. The technique consists of choosing an initial sample based on some probability scheme and then adding more units to the sample if the units originally selected meet some predefined conditions (Christman 1997). The Rao–Blackwell method was followed to obtain improved and unbiased estimators.

Fig. 1.

Four community and rural development blocks chosen for study from Upper Subansiri district, Arunachal Pradesh

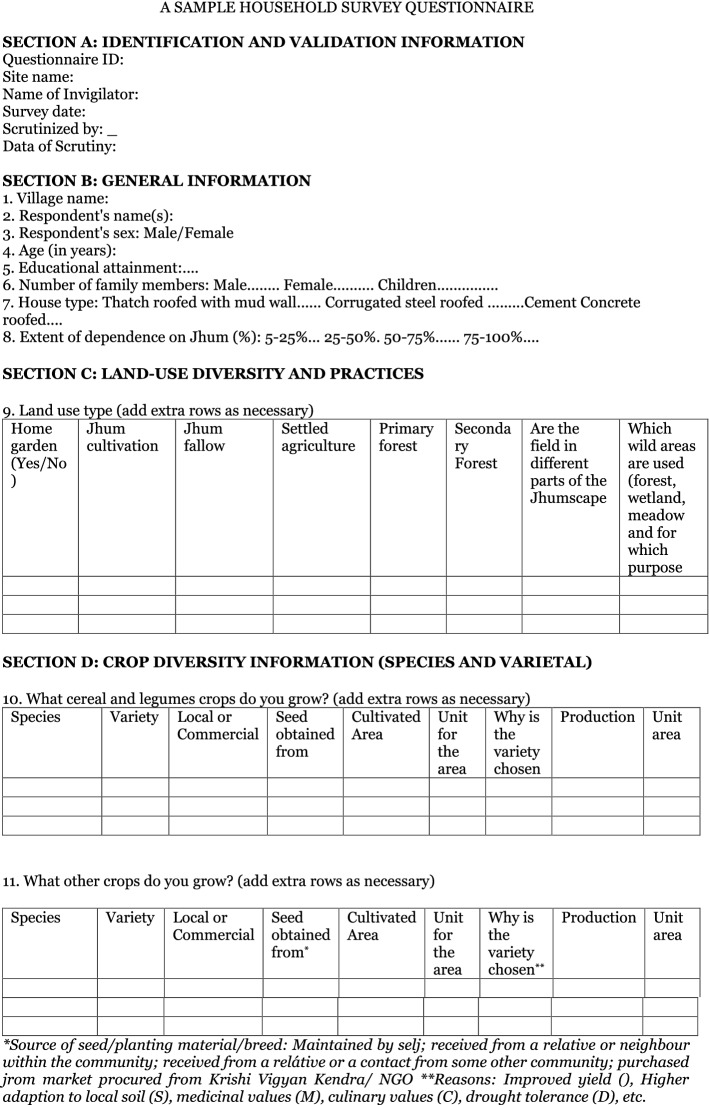

The survey schedule comprised of six sections, namely general information, land use and farming practices, crops (species and varieties), livestock, use of wild edible plants, and household expenditure (Annexe 1). The instrument (questionnaire) for data collection was in the local language and consisted of simple questions that required only brief answers: the wording was precise, brief, simple, and culturally appropriate. The questions were either open ended or involved multiple choices designed to get responses suitable for some kind of scoring or ranking. Basic information was collected on the following aspects: the household, farming systems, cropping period, duration of the fallow period, the extent of crop and animal diversity, and use of wild edible plants. The objective was to gather data on the diversity and production practices to identify the constraints on, as well as opportunities for, conserving agrobiodiversity. The name of each crop was recorded, along with its variety or cultivar, wherever known. Initially, each informant was asked to recall all the possible crops and kinds of livestock to ensure that all different types of crops (cereals and legumes, vegetables, fruits, spices), and breeds of livestock were recorded. In addition, valuable information was also gathered on jhum practices and participation of women therein. Data were collected by two field investigators, a man and a woman, along with one translator, all living within the study area. We also went on transect walks with ‘jhumia’s (practitioner of jhum) to find out why they keep and grow different kinds of trees and natural flora. Within the study site, the routes for the walks were chosen at random. Visits to randomly selected jhum plots and discussion with jhumias followed by triangulating information through the key informants (village heads, school headmasters, and KVK officials) were also part of the walk. The focus was on understanding how the jhum landscape is managed to promote agricultural productivity, to preserve biodiversity, and to ensure that farming is both resilient and stable.

Data analysis

The most widely used measures of biodiversity in ecology are species richness, the Shannon index, and the Simpson index (Pallmann et al. 2012). The present study used the Simpson index to measure Alpha diversity in the jhum system. Further, species density was measured using the following formula wherein a household was considered as a quadrat.

The documented species and breeds were divided into four basic food groups to assess the nutritional security of families, as defined by the National Institute of Nutrition’s manual on dietary requirements for Indians (National Institute of Nutrition 2011). Spices were introduced as a fifth group owing to their considerable culinary and medical relevance as described by the respondents. Despite the well-defined determinants of food security, there is little consistency in the way it is measured (Russell et al. 2018). Richness of crop species in a farming system is a potential predictor of food (in) security (Massawe et al. 2016; Mburu et al. 2016; Jones 2017), and the present study used one additional method to triangulate food security: the share of expenditure on food in the total household income was used as an indicator of household food security, because it is widely documented that the poorer and more vulnerable the household, the larger the share of household income spent on food. Many studies have assessed food security on the basis of per capita food expenditure (Adebayo et al. 2016; Melgar-Quinonez et al. 2006): a household was considered food insecure if it spent more than 75% of its income or a weighted two-thirds of the mean per capita income on food. Similarly, Smith and Subandoro (2007) considered a household as food insecure and highly vulnerable if it spent more than 75% of its income on food, whereas those households for which the corresponding proportion was less than 50% were considered food secure. Furthermore, prevailing jhum practices in the study area were analysed keeping in view the elements of agroecology as approved and described by FAO (2018).

Results

Socio-economic profile

As the association of socio-economic and agroecological factors plays a vital role in conserving diversity, it was studied. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics and some other relevant information on the respondent households (n = 97)

| Variable | Respondent households | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Mean | Standard deviation | Coefficient of variation (%) | |

| Age, years | |||||

| Young (18–35) | 11 | 11.34 | |||

| Middle (36–50) | 67 | 69.07 | 44.18 | 7.13 | 16 |

| Old (Above 50) | 19 | 19.59 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Man | 23 | 23.70 | |||

| Women | 74 | 76.30 | |||

| Educational attainment | |||||

| Illiterate | 5 | 5.15 | |||

| Primary school | 41 | 42.27 | |||

| High school and above | 51 | 52.58 | |||

| Family size (no. of members) | |||||

| Small (< 4) | 3 | 3.09 | |||

| Medium (4–8) | 87 | 89.69 | 6.1 | 1.74 | 28 |

| Large (> 8) | 7 | 7.22 | |||

| Type of home (construction) | |||||

| Thatched roof andmud walls | 28 | 28.87 | |||

| Roof of corrugated steel | 63 | 64.95 | |||

| Roof of cement concrete | 6 | 6.19 | |||

| Extent of dependence on jhum (%) | |||||

| 5–25% | 7 | 7.22 | |||

| 26–50% | 38 | 39.20 | |||

| 51–75% | 33 | 34.00 | |||

| 76–100% | 19 | 19.59 | |||

The mean age of respondents was approximately 44 years and about one-fourth (24%) of them were women. Majority of the respondents had studied at least up to high school. The average family comprised six members. About 65% of the respondents lived in homes with roofs of corrugated steel. The level of their dependence on jhum varied: approximately 46% of the respondents put the level at 50% and the rest (approximately 54%) said they were totally dependent on jhum for their livelihood.

Species diversity

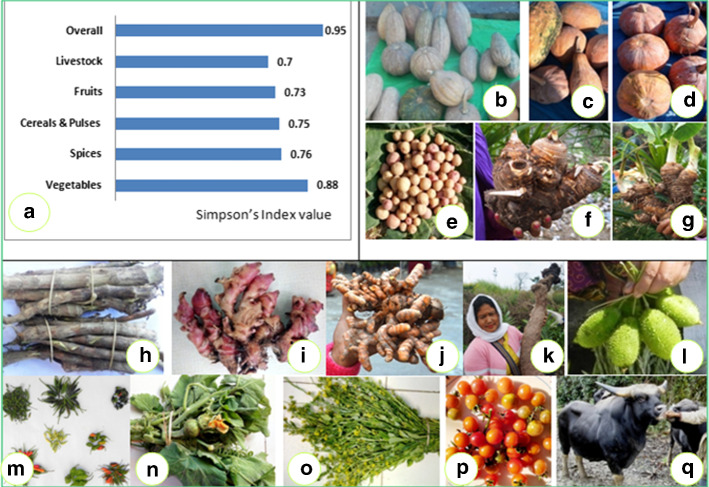

The study categorized economic biomass from jhum into five food groups—cereals and legumes, vegetables, fruits, spices, and livestock—to examine the species richness and density (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Species richness and density (percent) in the sample area, by food group

Each of the five food groups was dominated by at least three species of crops or of livestock (Fig. 2), which emphasizes the diversity inherent in traditional farming, which buffers the system against risks and enhances food security by ensuring supply of food round the year. At least fifteen species of crops or of livestock representing each food group were part of the high-density jhum farming.

Diversity of crops and livestock species

The diversity of crops and livestock in jhum (Fig. 3) was high, as evident from the Simpson’s Index of 0.95. The species diversity was more or less equally distributed among the five food groups except vegetables, which showed a markedly higher diversity and, being rich in micronutrients, may be a good indicator of nutritional security. For example, butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata) was found in abundance and showed wide variety in terms of the size, skin colour, and flesh colour of its fruit (Fig. 3b–d) and was put to multiple uses; tender vine and flowers of pumpkin are also eaten as a vegetable; and the pseudostem, flowers, and immature fruit of Musa spp. are consumed as vegetables, while the ripe fruit is consumed as a table fruit. This ensures year-round availability of vegetables.

Fig. 3.

The diversity of crops and livestock in jhum. a Simpson’s Index of crops and livestock species; b–d Landraces of Cucurbita moschata; e Landrace of Solanum tuberosum; f–h Landraces of Colocasia esculenta; i Landrace of Zingiber officinale; j Curcuma longa; k Dioscorea spp.; l Momordica charantia; m Landraces of Capsicum spp.; n Tender vine, flower, and flower buds of Cucurbita moschata; o Brassica juncea; p Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme; q Bos frontalis

Wild edible plants

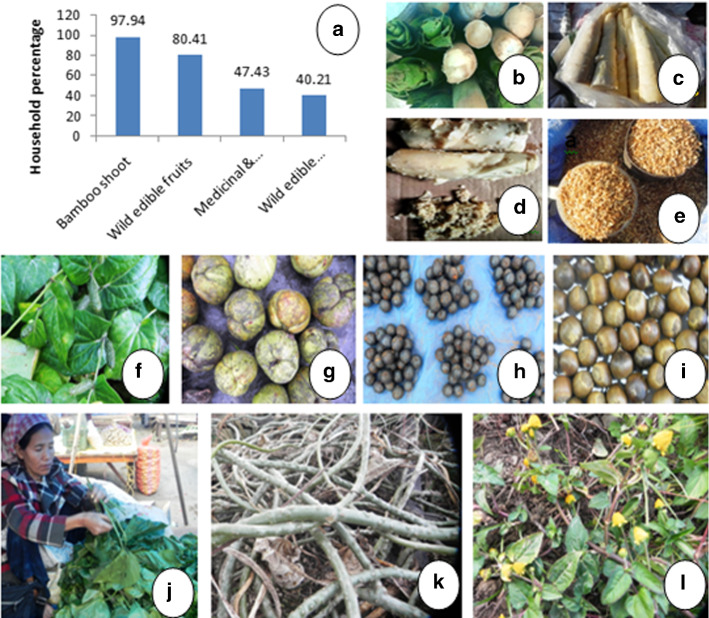

The extent of consumption of wild edible plants by the surveyed households is presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Consumption of wild edible plants. a percentage of households consuming various wild edible plants; b fresh shoots of bamboo (Bambusa tulda); c and d traditional products from fermented bamboo; g dried shoots of bamboo; f Piper longum; g Dillenia indica; h Livistona jenkinsiana; i Castanopsis indica; j Clerodendrum glandulosum; k Tinospora crispa, and l Spilanthes acmella

Fresh shoots of bamboo are the most commonly consumed food obtained from the wild. This evidently denotes its sufficient availability and access to all. Bamboo shoots are consumed either fresh when they are in season (May to October) or dried, fermented, or pickled for off-season consumption, thus ensuring a stable supply round the year. The most common edible species of bamboo in the study area are Bambusa tulda, B. pallida, Dendrocalamus hamiltonii, and D. giganteus. The consumption of wild edible fruits, mushrooms, and medicinal plants was also reported by a significant number of households, which confirms their availability. Further, bamboo is the main substrate for various ethnic fermented foods, namely eeku (Fig. 4c, d), eep and eup (Fig. 4e), and eyup and hiyup, which are traditionally prepared by the people of Nyishi and Galo tribes in the study area. In addition, jhum agrobiodiversity offers a wide range of food products that include dry meat in powder form seasoned with herbs; other meat by-products with rice flour, maize, or fruit; indigenous blood sausages; and products from animal fat preserved in containers of dry gourds or bamboo culms. In case of livestock, despite the indigenous breeds’s low growth rate and low productivity, the locals prefer the meat of indigenous pigs to that of commercial breeds because these pigs have important genetic traits such as good mothering ability, low nutrient requirements, early maturity, and greater resistance to parasites and diseases as revealed by many community elders during the transect walks. Likewise, the species Bos frontalis (Fig. 3q) is socio-culturally important to the indigenous people and is the object of sacrifice during festivals as part of the ritual offerings. Indeed, the mithun may be thought of as a keystone species culturally for the indigenous people of Arunachal Pradesh (because it shapes their cultural identity, reflected in the fundamental roles it has in their diet, in medicine, in spiritual practices, and as a source of different materials).

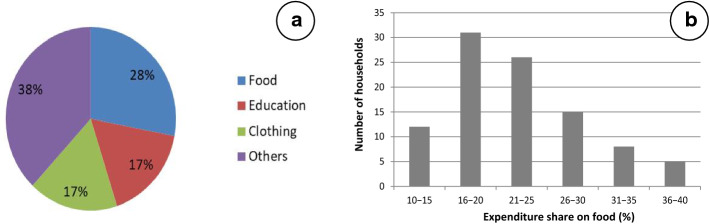

Household expenditure

Adopting the methodology of Smith and Subandoro (2007), the study categorized the households based on the proportion of income spent on food to identify those households that are the most vulnerable and food insecure (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Spending pattern of households. a expenditure on food, education, clothing, and other items; b classification of households by the proportion of income spent on food

Food claimed a little more than a quarter of the budget of a typical household, followed by education and clothing. Among the heads of expense that were categorized as other expenses were religious functions, festivals, repairs to the house, livestock, and other miscellaneous goods or services (Annexe 2). Because food claims less than 50% of the total income, the studied population can be considered food secure. This clearly underscores the contribution of jhum to food and nutritional security. The extant agrobiodiversity in jhum fulfilled almost all the dietary needs of the indigenous people and made them self-reliant, lowering their dependence on the market.

Prevailing jhum practices

The transect walks in the study area provided ample learning about jhum as practised in the area. Site selection and clearing, burning, sowing, weeding, protection, harvesting, and storing are the main elements of traditional jhum farming. At each step of cultivation, specific and critical decisions must be made on the location, schedule, crops, and labour inputs. This decision-making is extremely important, and it must consider agro-climatic and environmental variables as well as social and cultural considerations. The jhum cycle usually starts in December–January with the calls of a certain bird (chou pou), insects (goi), or other location-specific signs. This cycle entails the creation of new plots based on the presence or absence of specific plants. The selection criteria are also influenced by the soil type in the area and the type of crop that will be grown. Some spots are considered sacred owing to the presence of unique plant species, whereas some zones near settlements are deemed cursed, and cutting of trees is strictly prohibited in such areas.

As understood from the key informants of Tagin tribe, in choosing sites for jhum, the ethnic people make a point of avoiding areas that are dominated by rare or medicinally significant species. They avoid cutting certain large trees (which are considered abodes of the spirits and of gods) because they realize the importance of those trees to the immediate ecology of the site and its long-term viability. In addition to providing shelter for numerous birds, animals, and insects, such large trees serve as guides in carrying out farming chores. The ethnic people in the study area avoid removing certain tree species while clearing a patch of forest to avoid invoking the wrath of the spirits of the woods. Sengri and sengne (Ficus sp.) are two trees that are believed to harbour ghosts, and cutting or using their wood as firewood is forbidden. Cutting and slashing are performed by a select group of skilled individuals, who cut trees of medium girth to a specific height while keeping in mind the crop to be grown at that location and keeping the height of slashed trees 15–20 cm lower than the expected height of the crop at maturity. Such trees were also found to be evenly distributed. The next phase of jhum begins in January-February and is heralded by calls of the pipiar bird and flowering of specific wild species such as the Malabar silk cotton tree (Bombax ceiba); the phase entails burning the slashed vegetation and then removing the charred residues. The jhumias never set fire to the slashed areas indiscriminately but understand the science of fire management, and a ceremony is organized around the task to keep them awake all night to prevent the fire from spreading beyond its confines. The jhumias avoid eating a full meal during this time, lest they should doze off.

Farmers sow rice by dibbling, which involves making a small hole in the earth with a sharpened stick and dropping two to three seeds into the hole—neither more nor fewer, a skill gained through years of experience. Because the land is not ploughed, the practice corresponds to ‘zero tillage’. Without adding external inputs, sowing is mostly done by women, and it leaves the soil virtually undisturbed. Jhum is the centre of almost all their festivities and ceremonies, and they maintain a close eye on their fields for timely weeding and other activities. Farmers maintain a thin cover of weeds to avoid splash erosion during rainstorms. Weeds are piled up throughout the field, and as they decay, leachates from the heap offer nutrients to the crops, which mop up the nutrients, preventing them from being lost from the fields. Harvesting takes place throughout October and November, with women gathering the panicles of rice in a bunch and carrying them in a bamboo basket known as egin. Thus, mixed cropping allows for sequential harvesting. The dried grains are kept in a unique rodent-proof granary known as nehu. Before they use fresh grains for food, they set aside a small quantity as seed. It is forbidden to mix seeds from different varieties. In the study area, farmers move on to the next patch after completing the cultivation phase, leaving the earlier fields fallow for 10–12 years, which is long enough for the vegetation to renew and regenerate into mature secondary forests.

As can be inferred from Table 3, gender equality is central to jhum. Except burning the slashed vegetation, which is a task performed only by men, all the phases and tasks involved in jhum are shared equally between men and women, with children helping out now and then. This division of labour improves efficiency and is characteristic of family farming. Furthermore, women are also the keepers of seeds and foragers of wild edible plants from forest fringes in jhum landscapes.

Table 3.

Distribution of work by gender in shifting cultivation in the study area

| Stage of shifting cultivation | Activity | Children | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation | Slashing | ○ | ●● | ●●● |

| Burning | ●●● | |||

| Piling and reburning | ○ | ●● | ●● | |

| Cultivation | Dibbling | ○ | ●●● | |

| Planting | ●●● | ○ | ||

| Weeding | ○ | ●●● | ●● | |

| Safeguarding | Fencing | ○ | ●●●● | |

| Guarding | ●● | ●●● | ||

| Post-harvest | Harvesting | ○ | ●● | ●● |

| Threshing | ●●● | ●● | ||

| Selling of surplus | Hauling | ●● | ●●● | |

| Selling of surplus | ●●● | ●● |

●, major involvement; ○, role more as a helper

Discussion

Agroecology is centred on using biodiversity and ecosystem services in crop production (Gliessman and Tittonell 2015; FAO 2018). Hence, an understanding of agroecological production and its benefits for biodiversity conservation, food security, and overall improved quality of life can help in shaping new social norms for sustainability (HLPE 2019). The present study provides ample evidence that the jhum system in Upper Subansiri district, a part of the eastern Himalayas, is beneficial for biodiversity conservation, food and nutritional security, and many more ecosystem services in such subsistence farming and may help in shaping appropriate social norms to ensure a sustainable food system. This aspect is discussed in the following sections.

Agrobiodiversity and household food security

The present study documented species diversity in jhum as evident in more than thirty species representing many landraces and four non-descript breeds of livestock. The food basket was supplemented with wild edible plants collected from fringes of forests and fallow lands that are a part of the jhumscape. This jhum agrobiodiversity ensures food security and nutrition because each of the five food groups was dominated by at least three crops or livestock species (Fig. 2), a mix that protects the system from hazards and improves food security by assuring year-round supply of food. The high-density jhum farming included at least fifteen varieties of crops or livestock from five food groups. Each of the species has some specific features; for instance, rice landraces had much higher dietary fibre and lipid content than improved rice cultivars (Longvah and Prasad 2020). Further, the rice landraces in the study area, such as Yabar Red, Yamukh, Rutte, Pimin Minli, Balii, Bali (Red), Bali (White), Amtte, and Aazo have significantly low levels of phytates and therefore have significant nutritional implications. If linked with genetic and local agro-morphological features, the nutritionally different groups of rice landraces hold a great potential for rice breeding. Similarly, butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata) is a vegetable crop that is widely recognized as a functional food (Adams et al. 2011). The fruit is high in vitamin A and was found in abundance and varied widely in terms of size, skin colour, and flesh colour in the study area (Fig. 3b–d) and is put to multiple uses (Kaur et al. 2019). Backyard poultry is an accessible source of protein-rich food and supplemental income for poor households (Wong et al. 2017). Bamboo is not only delicious but bamboo shoots are also high in minerals, carbohydrates, proteins, and fibre and low in fats and sugars, making it a useful food to overcome malnutrition. Bamboo shoots have also been shown to provide health benefits in the treatment of cancer and cardiovascular illnesses and a useful food for weight loss and improved digestion (Basumatary et al. 2017). Tender shoots –young culms of bamboo—were consumed by almost all the households (Fig. 4a). Bamboo has multiple uses, survives forest fires, and grows well mainly on jhum fallows. Apart from the use of bamboo for fencing, construction, roofing, crafts, and ritual altars, bamboo shoots are also used in making many fresh and fermented ethnic foods and are now considered a super food and also have medicinal uses (Chongtham and Bisht 2020). Bamboo can contribute greatly in achieving the SDGs. The households spent less on food (Fig. 5) but that refers to food that they bought: the households consumed more home-grown food because they had access to a great variety of food sources. However, households with access to fewer crop species spend more on food (Jones 2017).

Jhum agroecosystems offer multiple benefits as vegetational diversification in jhum is much higher than in monoculture. Therefore the mosaic landscape (jhum fields, fallow lands, and forest fringes) provides ecosystem services important for biodiversity conservation, rural livelihoods, and long-term production of food and other goods; at the same time, the landscape also shelters animals, facilitates their movement, and maintains the many natural processes (Van Noordwijk et al. 2012; Kremen and Merenlender 2018). Intraspecific diversity (landraces) is critical in adapting to climate change and ensuring food and nutrition security by offering farmers more alternatives for mitigating climatic risks and making their farming systems more resilient (Renard and Tilman 2019; Pilling et al. 2020). Unfortunately, all these agroecological processes are seen in isolation from jhum, which also values the local, empirical, and indigenous knowledge of farmers.

Sustaining ethnic culture and food traditions

Cultivated and wild biodiversity in the jhum landscape contributed to many traditional ethnic, culinary, and ethnomedicinal preparations; for example, jhum rice is the main substrate for many traditionally prepared alcoholic beverages such as apong, opo, pone, pona, and nyongin. In fact, apong–the most popular cereal-based fermented alcoholic beverage –is prepared from rice (the glutinous jhum rice) and consumed by almost all tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, as are bamboo-based fermented foods (Roy et al. 2017; Shrivastava et al. 2020). The by-products of jhum, particularly maize, the pseudostem of banana, and tuber crops are used to feed poultry and pigs. Another livestock species, popularly referred to as the mountain cattle or mithun (Bos frontalis), now features in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (Memon et al. 2018). Owning mithun (Fig. 3q) is a matter of pride and the animal also serves as a native currency for barter. Mithun makes a great wedding gift; can be traded in settling legal disputes; is central to a number of cultural festivities and local ceremonies; and also plays an ecological role in the conservation of broad-leaved subtropical forests because of its semi-wild nature (Dorji et al. 2021). In Arunachal Pradesh, during 2007–2012, increased domestication of the species to roughly 25% served to lower hunting pressure on other species (Chavan et al. 2018). With regards to medicinal plants, Murtem and Chaudhry (2016) documented 269 plant species from 77 families in Upper Subansiri district. Among the edible species, 81 were trees, 74 were shrubs, 71 were herbs, and 37 were climbers; however, because of anthropogenic pressure, the availability of several of these species may be seriously constrained in the near future.

Jhum agroecological practices

It was clear from the survey that jhum is a method of family farming that involves zero tillage, mixed cropping with high crop diversity, locally available inputs, and extensive use of local wisdom or ecological knowledge—in short, jhum is based on sound ecological concepts and principles. Despite minor differences in jhum practices among different tribes or even villages, the core concepts of community life in north-eastern India remains the same and share many similarities with South East Asia as well (Erni 2021). The indigenous and local knowledge and practices in jhum appear particularly promising in achieving several SDGs, especially SDG1 (No Poverty), SDG2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG15 (Life on land), as observed by Dasgupta et al. (2021). Indeed, the jhum system provides local people with culturally appropriate foods while also preserving their cultural food habits, which have enormous potential for improving food security (Pandey et al. 2022). By building bioregional economies and maintaining links with customs, traditions, and cultural events, such food systems can bring about suitable grass-roots-level changes in socioecological systems.

However, among the many practices or steps, one element of this agroforestry system that draws considerable criticism is the burning of vegetation after clearing (Nigh and Diemont 2013) despite the ecosystem services rendered by such a multifunctional landscape. Indeed, such seasonal and spatially distributed burning is known to benefit biodiversity, helps in controlling forest fires, and reduces the emissions of carbon (Bilbao et al. 2010; Russell-Smith et al. 2013; Welch et al. 2013). In fire-prone environments, fire has long been thought to benefit biodiversity. Actually, fire has been used to promote biodiversity conservation as a forest management technique (Berlinck and Batista 2020). In controlled, or ‘prescribed’, burning, as in the case of jhum, a recent study by Radford et al. (2020) found that the early dry-season burning of up to 30% of total area resulted in beneficial animal responses, whereas late dry-season burning proved largely detrimental to vulnerable species. Mandal and Raman (2016) reported that more species of tropical forest-dwelling birds are supported by jhum than by oil palm or teak plantations.

In ecological terms, burning increases the number of potential niches by generating gaps and creating snags and deadwood patches; as a result, fires boost evolutionary processes by increasing the number of potential ecological niches (Pausas and Keeley 2019). However, a blaze in jhum should not be confused with fires used for clearing peat lands for oil palm plantations. Thus, no immediate and viable fire-free options are available to those dependent on jhum. The alternatives that are being promoted by the state, such as monoculture of cash crops including plantations of oil palm and rubber, are far away from agroecological principles and diversity and an obstacle to agroecological transition to more sustainable food systems (Altieri and Nicholls 2020b). Above all, these ecological gains from jhum are mainly dependent on the length of the fallow period (10–15 years) and the customs and laws that governs jhum.

Conclusions

The study has quantified jhum agrobiodiversity and documented its contribution to food and nutritional security and examined jhum agroecological dynamics in eleven villages, which are part of the Eastern Himalayas global biodiversity hotspot. The study captured the rich pool of useful species of plants and livestock—useful not as isolated resources but as components of an ancient agroforestry system, namely jhum. The practices in jhum are often based on agroecological principles and represent almost all the ten elements of agroecology as approved by the FAO recently, of which diversity is the first and foremost element. However, the seasonal burning in jhum has maligned this traditional agroforestry system being followed by indigenous peoples in the absence of imminent and viable fire-free alternatives. As a consequence, the system of jhum is no longer considered a part of global biodiversity conservation efforts– although jhum contributes a great deal to that effort—merely because of the unreasonable and ill-informed focus on burning.

In view of the above findings, we propose that the present policies and strategies that seek to replace jhum with conventional and so-called modern methods of farming be suitably amended and anew framework and strategies be put in place. These strategies should aim at making appropriate interventions to conserve agrobiodiversity in jhum, optimize the exploitation of indigenous genetic resources, and encourage farming systems that are environment friendly, ensure food and nutritional security, achieve harmony with indigenous culture, and introduce better forms of jhum that supplement traditional knowledge with advanced science. We argue that the Global Biodiversity Framework must include conservation actions in multifunctional jhum landscapes in the three ‘2030 Action Targets’ to reach its goals of biodiversity recovery and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, because jhum harbours rich biodiversity, offers valuable ecosystem services, and is based on sound agroecological principles.

Annexe 1

Annexe 2

Author contributions

Conceptualization: DKP and PA; methodology: DKP and PA; formal analysis and investigation: PA and KCM; writing the first draft: DKP and PA; revising and editing the first draft: KCM and PK; funding acquisition: DKP; resources: KCM and PK; supervision: PK.

Funding

This study was supported by the Agricultural Extension Division, Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), New Delhi, India (Grant Reference: A.Extn.26/10/2015-AE-I/01).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary files.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Research Advisory Committee, Central Agricultural University, Manipur, India. Appropriate consent processes were followed for all research participants.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dileep Kumar Pandey, Email: dkpextension@gmail.com.

P. Adhiguru, Email: p.adhiguru@gmail.com

Kalkame Cheran Momin, Email: kalkame.momin@gmail.com.

Prabhat Kumar, Email: prabhatflori@gmail.com.

References

- Adams GG, Imran S, Wang S. The hypoglycaemic effect of pumpkins as anti-diabetic and functional medicines. Food Res Int. 2011;44(4):862–867. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo O, Olagunju K, Kabir SK, Adeyemi O. Social crisis, terrorism and food poverty dynamics: evidence from Northern Nigeria. Int J Econ Financial Issues. 2016;6(4):1865–1872. [Google Scholar]

- Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1958–1972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almond RE, Grooten M, Peterson T (2020) Living planet report 2020-bending the curve of biodiversity loss. World Wildlife Fund

- Altieri M, Nicholls C. Biodiversity and pest management in agroecosystems. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri MA, Nicholls CI. Agroecology and the emergence of a post COVID-19 agriculture. Agric Hum Values. 2020;37(3):525–526. doi: 10.1007/s10460-020-10043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altieri MA, Nicholls CI. Agroecology and the reconstruction of a post-COVID-19 agriculture. J Peasant Stud. 2020;47(5):881–898. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2020.1782891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon CM, Sundstrom WA, Gómez ME, et al. Explaining the ‘hungry farmer paradox’: smallholders and fair trade cooperatives navigate seasonality and change in Nicaragua’s corn and coffee markets. Glob Environ Change. 2014;25:133–149. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basumatary A, Middha SK, Usha T, Basumatary AK, Brahma BK, Goyal AK. Bamboo shoots as a nutritive boon for Northeast India: an overview. 3 Biotech. 2017;7(3):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0796-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beillouin D, Ben-Ari T, Makowski D. Evidence map of crop diversification strategies at the global scale. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14(12):123001. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab4449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berlinck CN, Batista EK. Good fire, bad fire: it depends on who burns. Flora. 2020;268:151610. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2020.151610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhan S, Behera UK. Conservation agriculture in India—problems, prospects and policy issues. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2014;2(4):1–12. doi: 10.1016/S2095-6339(15)30053-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbao BA, Leal AV, Méndez CL. Indigenous use of fire and forest loss in Canaima National Park, Venezuela. Assessment of and tools for alternative strategies of fire management in Pemón indigenous lands. Hum Ecol. 2010;38(5):663–673. doi: 10.1007/s10745-010-9344-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht IS, Rana JC, Jones S et al (2021) Agroecological approach to farming for sustainable development: the Indian scenario. https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/78809. Accessed on 16 Jan 2022

- Cairns M. Shifting cultivation policies: Balancing environmental and social sustainability. Boston: CABI; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouli C, General R. Census of India 2011. Provisional population totals. New Delhi: Government of India; 2011. pp. 409–413. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan S, Yuvaraja M, Sarma HN. Bos Frontalis (Mithun): a flagship semi-domesticated mammal and its potential for ‘Mithun Husbandry’ development in Arunachal Pradesh. India Con Dai Vet Sci. 2018;1(5):134–138. doi: 10.32474/CDVS.2018.01.000122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chongtham N, Bisht MS. Bamboo shoot: superfood for nutrition, health and medicine. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Christman MC (1997) Efficiency of some sampling designs for spatially clustered populations. Environmetrics 8:145–166

- Dasgupta R, Dhyani S, Basu M, et al. Exploring indigenous and local knowledge and practices (ILKPs) in traditional jhum cultivation for localizing sustainable development goals (SDGs): a case study from Zunheboto district of Nagaland, India. Environ Manag. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00267-021-01514-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorji T, Wangdi J, Shaoliang Y, Chettri N, Wangchuk K. Mithun (Bos frontalis): the neglected cattle species and their significance to ethnic communities in the Eastern Himalaya—a review. Anim Biosci. 2021;34(11):1727. doi: 10.5713/ab.21.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erni C. Persistence and change in customary tenure systems in Myanmar. MRLG thematic study series # 11. Yangon: POINT MRLG; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . The 10 elements of agroecology: guiding the transition to sustainable food and agricultural systems. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker M. Epistemic injustice: power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- FSI . India state of forest report, forest survey of India. Dehradun: Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Giri K, Mishra G, Rawat M, et al. Traditional farming systems and agro-biodiversity in eastern Himalayan region of India. In: Goel R, Soni R, Suyal DC, et al., editors. Singapore: microbiological advancements for higher altitude agro-ecosystems & sustainability. Cham: Springer Nature; 2020. pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gliessman S, Tittonell P. Agroecology for food security and nutrition. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst. 2015;39(2):131–133. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2014.972001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomiero T. Food quality assessment in organic vs. conventional agricultural produce: findings and issues. Appl Soil Ecol. 2018;123:714–728. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graeub BE, Chappell MJ, Wittman H, et al. The state of family farms in the world. World Dev. 2016;87:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadani H, Rashid SM, Parrah JD, et al. et al. Traditional farming practices and its consequences. In: Dar GH, Bhat RA, Mehmood MA, Hakeem KR, et al.et al., editors. Singapore: microbiota and biofertilizers. Cham: Springer; 2021. pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Heinimann A, Mertz O, Frolking S, et al. A global view of shifting cultivation: recent, current, and future extent. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184479. doi: 10.1371/journalpone0184479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HLPE (2019) Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome

- Hunter D, Guarino L, Spillane C, McKeown PC. Introduction: agricultural biodiversity, the key to sustainable food systems in the 21st century. In: Routledge handbook of agricultural biodiversity. London: Routledge; 2017. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES (2019) Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services

- Jones AD. On-farm crop species richness is associated with household diet diversity and quality in subsistence-and market-oriented farming households in Malawi. J Nutr. 2017;147(1):86–96. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.235879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juo AS, Manu A. Chemical dynamics in slash-and-burn agriculture. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 1996;58(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/0167-8809(95)00656-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karki MB (2017) Policies that transform shifting cultivation practices: linking multi-stakeholder and participatory processes with knowledge and innovations. In: Shifting cultivation policies: balancing environmental and social sustainability, pp 889–916

- Kaur S, Panghal A, Garg MK, Mann S, Khatkar SK, Sharma P, Chhikara N. Functional and nutraceutical properties of pumpkin–a review. Nutr Food Sci. 2019;502:384–401. doi: 10.1108/NFS-05-2019-0143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr RB, Madsen S, Stüber M, et al. Can agroecology improve food security and nutrition? A review. Glob Food Sec. 2021;29:100540. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kindon S, Pain R, Kesby M. Participatory action research: origins, approaches and methods. Participatory action research approaches and methods. London: Routledge; 2007. pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Okada KI, Mori AS. Reconsidering biodiversity hotspots based on the rate of historical land-use change. Biodivers Conserv. 2019;233:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.02.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen C, Merenlender AM. Landscapes that work for biodiversity and people. Science. 2018;362(6412):eaau6020. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachat C, Raneri JE, Smith KWet. Dietary species richness as a measure of food biodiversity and nutritional quality of diets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(1):127–132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1709194115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levidow L, Pimbert M, Vanloqueren G. Agroecological research: conforming—or transforming the dominant agro-food regime? Agroecol Sustain Food Syst. 2014;38(10):1127–1155. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2014.951459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Longvah T, Prasad VS. Nutritional variability and milling losses of rice landraces from Arunachal Pradesh, Northeast India. Food Chem. 2020;318:126385. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowder SK, Sánchez MV, Bertini R. Farms, family farms, farmland distribution and farm labour: what do we know today? FAO agricultural development economics working paper 19–08. Rome: FAO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal J, Shankar Raman TR. Shifting agriculture supports more tropical forest birds than oil palm or teak plantations in Mizoram, Northeast India. Condor: Ornithol Appl. 2016;118:345–359. doi: 10.1650/CONDOR-15-163.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massawe F, Mayes S, Cheng A. Crop diversity: an unexploited treasure trove for food security. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21(5):365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mburu SW, Koskey G, Kimiti JM, et al. Agrobiodiversity conservation enhances food security in subsistence-based farming systems of Eastern Kenya. Agric Food Sec. 2016;5(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40066-016-0068-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MD, Tiemann LK, Grandy AS. Does agricultural crop diversity enhance soil microbial biomass and organic matter dynamics? A meta-analysis. Ecol Appl. 2014;24(3):560–570. doi: 10.1890/13-0616.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melgar-Quinonez HR, Zubieta AC, MKNelly B, et al. Household food insecurity and food expenditure in Bolivia, Burkina Faso, and the Philippines. J Nutr. 2006;136(5):1431S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.5.1431S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memon S, Wang L, Li G, et al. Isolation and characterization of the major histocompatibility complex DQA1 and DQA2 genes in gayal (Bos frontalis) J Genet. 2018;97(1):121–126. doi: 10.1007/s12041-018-0882-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtem G, Chaudhry P. "An ethnobotanical note on wild edible plants of upper Eastern Himalaya, India". Braz J Biol Sci. 2016;3(5):63–81. doi: 10.21472/bjbs.030506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Nutrition (2011) Manual, a dietary guideline for Indians. 2:89–117

- Nigh R, Diemont SA. The Maya milpa: fire and the legacy of living soil. Front Ecol Environ. 2013;11(s1):e45–e54. doi: 10.1890/120344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NRSC (2019) Land use/land cover database on 1:50,000 scale, natural resources census project, LUCMD, LRUMG, RSAA, National Remote Sensing Centre, ISRO, Hyderabad

- Pallmann P, Schaarschmidt F, Hothorn LA, et al. Assessing group differences in biodiversity by simultaneously testing a user-defined selection of diversity 544 indices. Mol Ecol Resour. 2012;12(6):1068–1078. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey DK, Momin KC, Dubey SK, Adhiguru P. Biodiversity in agricultural and food systems of jhum landscape in the West Garo Hills, north-eastern India. Food Secur. 2022;16:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01251-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SK, Sharma A, Singh GS. Traditional agricultural practices in India: an approach for environmental sustainability and food security. Energy Ecol Environ. 2020;5(4):253–227. doi: 10.1007/s40974-020-00158-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pausas JG, Keeley JE. Wildfires as an ecosystem service. Front Ecol Environ. 2019;17(5):289–295. doi: 10.1002/fee.2044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pilling D, Bélanger J, Hoffmann I. Declining biodiversity for food and agriculture needs urgent global action. Nat Food. 2020;1(3):144–147. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0040-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan A, Chan C, Roul PK, Halbrendt J, Sipes B. Potential of conservation agriculture (CA) for climate change adaptation and food security under rainfed uplands of India: a transdisciplinary approach. Agric Syst. 2018;163:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2017.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radford IJ, Woolley LA, Corey B, et al. Prescribed burning benefits threatened mammals in northern Australia. Biodivers Conserv. 2020;29:2985–3007. doi: 10.1007/s10531-020-02010-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raseduzzaman MD, Jensen ES. Does intercropping enhance yield stability in arable crop production? A meta-analysis. Eur J Agron. 2017;91:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2017.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renard D, Tilman D. National food production stabilized by crop diversity. Nature. 2019;571(7764):257–260. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1316-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Roy S, Rai C, Vidyamandira BM. Insight into bamboo-based fermented foods by Galo (Sub-tribe) of Arunachal Pradesh, India. Int J Life Sci Res. 2017;3(4):1200–1207. doi: 10.21276/ijlssr.2017.3.4.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J, Lechner A, Hanich Q, Delisle A, Campbell B, Charlton K. Assessing food security using household consumption expenditure surveys (HCES): a scooping literature review. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(12):2200–2210. doi: 10.1017/S136898001800068X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell-Smith J, Cook GD, Cooke PM, et al. Managing fire regimes in north Australian savannas: applying aboriginal approaches to contemporary global problems. Front Ecol Environ. 2013;11(s1):e55–e63. doi: 10.1890/120251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava K, Pramanik B, Sharma BJ. Ethnic fermented foods and beverages of India. Science history and culture. Singapore: Springer; 2020. Ethnic fermented foods and beverages of Arunachal Pradesh; pp. 41–84. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LC, Subandoro A (2007) Measuring food security using household expenditure surveys, vol 3. Intl Food Policy Res Inst

- Sodhi NS, Posa MR, Lee TM, et al. The state and conservation of Southeast Asian biodiversity. Biodivers Conserv. 2010;19(2):317–328. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9607-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stomph T, Dordas C, Baranger A, et al. Designing intercrops for high yield, yield stability and efficient use of resources: are there principles? Adv Agron. 2020;160(1):1–50. doi: 10.1016/bs.agron.2019.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker PB, Ingram JS, Struwe S. Effects of slash-and-burn agriculture and deforestation on climate change. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 1996;58(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/0167-8809(95)00651-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi SK, Vanlalfakawma DC, Lalnunmawia F. Shifting cultivation policies: balancing environmental and social sustainability. UK: CAB International Wallingford; 2017. Shifting cultivation on steep slopes of Mizoram, India; pp. 393–413. [Google Scholar]

- van Noordwijk M, Tata HL, Xu J, Dewi S, Minang PA. Segregate or integrate for multifunctionality and sustained change through rubber-based agroforestry in Indonesia and China. Agroforestry: the future of global land use. Netherlands: Springer; 2012. pp. 69–104. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet N, Mertz O, Heinimann A, et al. Trends, drivers and impacts of changes in swidden cultivation in tropical forest-agriculture frontiers: a global assessment. Glob Environ Change. 2012;22(2):418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wapongnungsang CM, Tripathi SK. Changes in soil fertility and rice productivity in three consecutive years cropping under different fallow phases following shifting cultivation. Int J Plant Soil Sci. 2018;25(6):1–10. doi: 10.9734/IJPSS/2018/46087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welch JR, Brondízio ES, Hetrick SS, Coimbra CE., Jr Indigenous burning as conservation practice: neotropical savanna recovery amid agribusiness deforestation in Central Brazil. PloS One. 2013;8(12):e81226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wezel A, Bellon S, Doré T, et al. Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2009;29(4):503–515. doi: 10.1051/agro/2009004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wezel A, Casagrande M, Celette F, et al. Agroecological practices for sustainable agriculture. A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2014;34(1):1–20. doi: 10.1007/s13593-013-0180-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, et al. Food in the anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JT, de Bruyn J, Bagnol B, et al. Small-scale poultry and food security in resource-poor settings: a review. Glob Food Secur. 2017;15:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF) (2020) Living planet report 2020—bending the curve of biodiversity loss. Almond REA, Grooten M, Petersen T (eds). WWF, Gland, Switzerland

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary files.