Abstract

An adult wild-caught corn snake (Elaphe guttata guttata) was presented for humane euthanasia and necropsy because of severe cryptosporidiosis. The animal was lethargic and >5% dehydrated but in good flesh. Gastric lavage was performed prior to euthanasia. Histopathologic findings included gastric mucosal hypertrophy and a hemorrhagic erosive gastritis. Numerous 5- to 7-μm-diameter round extracellular organisms were associated with the mucosal hypertrophy. A PCR, acid-fast stains, Giemsa stains, and an enzyme immunoassay were all positive for Cryptosporidium spp. PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis on gastric lavage and gastric mucosal specimens, and subsequent sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene, enabled a distinct molecular characterization of the infecting organism as Cryptosporidium serpentis. Until recently, studies on snake Cryptosporidium have relied on host specificity and gross and histopathologic observations to identify the infecting species. A multiple alignment of our sequence against recently published sequences of the 18S rRNA gene of C. serpentis (GenBank accession no. AF093499, AF093500, and AF093501 [L. Xiao et al., unpublished data, 1998]) revealed 100% homology with the C. serpentis (Snake) sequence (AF093499) previously described by Xiao et al. An RFLP method to differentiate the five presently sequenced strains of Cryptosporidium at this locus was developed. This assay, which uses SpeI and SspI, complements a previously reported assay by additionally distinguishing the bovine strain of Cryptosporidium from Cryptosporidium wrairi.

Cryptosporidium is a 5- to 10-μm round protozoal parasite that affects the digestive epithelium of a variety of animal species. More than 20 species of Cryptosporidium have been identified with questionable host specificity (8, 17). Recently, questions regarding identification of the organism to species level have been brought to the forefront for five reasons, as follows. (i) The organism has been identified as causing a fatal diarrhea in immune-compromised humans (6). (ii) There have been numerous water- and food-borne outbreaks of the disease in humans (22). (iii) There is no effective treatment for the disease. (iv) Water treatment protocols lack effective disinfection methods to rid drinking water of viable organisms (22, 27). (v) A variety of environmental sources may be contaminated with oocysts, and therefore, they may harbor a variety of different species of Cryptosporidium (11, 23). Identification of Cryptosporidium organisms to species level is important because species-specific pathogenicity to humans has not yet been determined. Until we are able to determine the specificity of the different species of Cryptosporidium, we cannot determine the epidemiological significance of its presence within environmental samples (i.e., understanding its importance and implementing control methods).

In snakes, the absence of an effective treatment for cryptosporidiosis necessitates euthanasia to eliminate patient suffering and prevent further spread of the parasite. Historically, oocyst size and location in the host have been used in identification to species level (1a, 8, 16, 17, 21). However, a recent, sequence-specific PCR has been used to distinguish Cryptosporidium parvum from other species (4). Leng et al. (15) have described a PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method to analyze sequence variation of the 18S rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium spp. The high degree of sequence homology present in the 18S rRNA genes among different isolates and species of Cryptosporidium (3, 13, 14) allows the use of specific primers to amplify a wide range of Cryptosporidium species. Concomitant RFLP analysis is capable of exploiting any subtle differences found in these highly homologous nucleotide areas, provided restriction sites which enable differentiation exist.

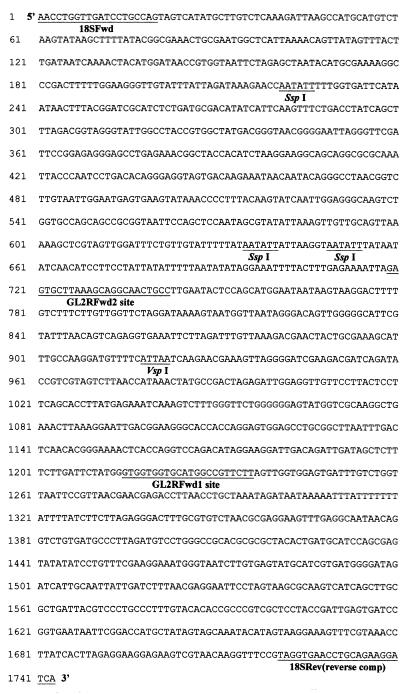

In this study, two oligonucleotide primers, sequences 18SFwd (5′-AACCTggTTgATCCTgCCAg-3′) and 18SRev (5′-TgATCCTTCTgCAggTTCACCTA-3′) (GenBank accession no. L16997) (2a, 17a) were used to amplify ca. 1,750-bp fragment of the 18S rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium. These primers target the 18S rRNA gene of all presently sequenced species of Cryptosporidium. This fragment was analyzed by RFLP and sequenced. We give the resulting complete nucleotide sequence of the 18S rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium serpentis (1,743 bp; GenBank accession no. AF151376) from Elaphe guttata guttata and align the sequence against other known C. serpentis sequences at this locus. Based on our results we suggest an RFLP-based assay capable of distinguishing five species of Cryptosporidium and of discerning bovine C. parvum from Cryptosporidium wrairi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and tissue preparation.

Gastric lavage was performed prior to euthanasia, and the contents were collected in a 10-ml sterile tube. The animal was euthanized with an intracardiac injection of 80 mg of pentobarbital sodium. A complete necropsy was performed. The contents of the large intestine were collected in a 1.5-ml sterile microcentrifuge tube. The gastric and intestinal mucosae were gently scraped, and the contents were collected into 1.5-ml sterile microcentrifuge tubes. Tissues were formalin fixed and paraffin embedded, and slide preparations were stained with hematoxolin and eosin, as well as Giemsa stain (20), for histological examination.

Staining procedures.

Acid-fast stains were applied to prepared slides (20). In brief, slide preparations of the specimens were heat fixed and the slides were flooded with Carbolfuchsin stain for 5 min over continuous heat. The slides were then washed with distilled water, followed by decolorization with acid alcohol. Methylene blue was chosen as the counterstain and applied for 1 min. The slides were then washed with distilled water, blotted dry, and examined for the presence of acid-fast organisms.

A Cryptosporidium genus-specific enzyme immunoassay (EIA) with a sensitivity of 20 ng of Cryptosporidium-specific antigen/ml was performed (ProSpect Cryptosporidium Microplate Assay; Alexon Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.).

DNA extraction.

C. parvum oocysts were provided by the National Institutes of Health AIDS Reagent Program and used as the positive control in this study. Control and snake specimens were treated identically as follows. Fifty microliters of sample was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was suspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer containing 1 M Tris-HCl, 0.5 M EDTA, 0.4 mg of proteinase K/ml, and 10% Triton X-100. The samples were frozen at −80°C for 5 min, then thawed at 75°C for 5 min. This freeze-thaw cycle was repeated a total of four times. Samples were then incubated at 75°C for 3 h and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant containing genomic DNA (gDNA) was collected. Ten microliters was used for PCR.

Molecular analysis.

Ten microliters of gDNA was added to a PCR mixture to make a 50-μl total reaction volume consisting of the following: 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 4.0 mM MgCl2, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP) (Gene Amp PCR Core Kit; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.), 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), 1 μM each primer, and sterile double-distilled H2O. Twenty microliters of the ca. 1,750-bp product was resolved by electrophoresis on 1% agarose. The resolved product was then excised from the gel and purified (GlassMAX DNA Isolation Spin Cartridge System; Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) to a volume of 40 μl with 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3)–0.1 mM EDTA. Five microliters of the purified product was then used as the template in a second round of amplification. PCR parameters, including molar volumes of constituents and cycling conditions of both amplifications, were identical (except for the template volume) in each amplification. A GeneAmp PCR System 9600 Instrument System was used for cycling: 35 cycles of 94°C (30 s), 68°C (30 s), and 72°C (90 s), followed by a 10-min extension step at 72°C. The ca. 1,750-bp product from the reamplification was excised and purified to a volume of 40 μl with 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3)–0.1 mM EDTA as above, and 10 μl was digested with DraI and VspI (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.) for 1 h at 37°C. Fragments were separated on agarose, visualized with ethidium bromide, and mapped. Negative controls containing water in place of gDNA as well as gDNA extracted from a negative snake were run concurrently.

The purified 1,750-bp reamplification product was cloned into pCR2.1 (TA Cloning Vector; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and transformed in INVaF′ competent cells (One Shot; Invitrogen). Ampicillin-resistant colonies were screened via restriction digestion with EcoRI (Promega) for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani broth, and the plasmid DNA was prepared for sequencing with the Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.) Clearcut Mini-Prep Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Originally, nonspecific annealing prevented direct sequencing from the 18SFwd and 18SRev primers used for PCR; therefore, automated sequencing (DNA Core Lab, University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami, Fla.) was initially primed from the M13 Forward (−20) primer in pCR2.1 (Invitrogen). Two more forward sequencing primers, GL2RFwd1 (5′-AAgAACGGCCATgCACCACCAC-3′) and GL2RFwd2 (5′-ggCAgTTgCCTgCTTTAAgCACTC-3′), were designed to complete the sequencing. To confirm the fidelity of Taq during polymerization and the resulting nucleotide sequence, three amplicons were analyzed independently, and their sequences were compared.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the 18S rRNA gene of C. serpentis from E. guttata guttata has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF151376.

RESULTS

Gross findings.

An adult wild-caught corn snake was presented for elective euthanasia and necropsy following a diagnosis of chronic cryptosporidiosis. This diagnosis was based on positive acid-fast staining of a gastric lavage specimen. The animal was >5% dehydrated but in good flesh. Digesta were noted within the intestinal lumens. Approximately 0.5 ml of excrement was collected. The gastric mucosa was mildly reddened and friable (possibly exacerbated in part by the gastric lavage). No other gross abnormalities were noted.

Histopathology.

Gastric sections were characterized by extensive hypertrophy of mucus-secreting cells lining the mucosal surface. Numerous 5- to 7-μm round extracellular organisms were associated with the hypertrophied cells. Giemsa stains on gastric tissue were positive for Cryptosporidium. Acid-fast staining and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay were positive for Cryptosporidium (Table 1). Organisms were positive for viability by trypan blue staining. Additionally, there were multiple foci of mixed inflammatory infiltrates in the areas that had the highest organism density. Inflammatory cells include heterophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages. Mild hemorrhage was also noted within areas of inflammation.

TABLE 1.

Results of acid-fast staining, EIA, and PCR test performed for detection of Cryptosporidium spp. on specimens collected from various locations in a corn snake (E. guttata guttata)

| Specimen | Result from:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acid-fast staining | EIA | PCR | |

| Gastric lavage | + | + | + |

| Gastric mucosa | + | + | + |

| Large-intestine mucosa | − | + | − |

| Feces | − | + | − |

Other changes included diffuse vacuolar degeneration in the liver. The remaining tissues (heart, lung, kidney, ovary, gall bladder, spleen, pancreas, brain, eye, skin, fat, trachea, esophagus, tongue, and intestines) were unremarkable.

PCR, RFLP, and sequencing.

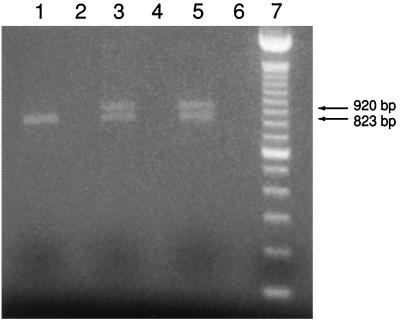

Amplification of gDNA extracted from a gastric lavage specimen and gastric mucosal scrapings with 18SFwd and 18SRev yielded visible bands at approximately 1,750 bp. No bands were visible after the first amplification for negative controls, fecal samples, and large-intestine mucosal samples. Both bands and the areas corresponding to 1,750 bp from the fecal and large-intestine mucosal samples were excised and reamplified. This reamplification elicited a substantial increase in the brightness of the gastric lavage and gastric mucosal bands at 1,750 bp over the initial amplification. No bands were visible for negative controls, feces, or intestinal mucosa in the 1,750-bp regions even after reamplification. Digestion of the reamplified products from the gastric lavage and intestinal mucosa with VspI resulted in visible fragments of approximately 920 and 820 bp. DraI did not cut the reamplification products (Fig. 1). These results are consistent with our sequence data showing a single VspI site beginning at position 918 and no sites for DraI (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Electrophoretic profile of the RFLP analysis from VspI digestion of the 18S rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium spp. Lane 1, C. parvum; lane 3, C. serpentis from gastric mucosa; lane 5, C. serpentis from gastric lavage; lane 7, 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco BRL). Lanes 2, 4, and 6 are empty. Arrows indicate previously reported digestion of C. muris 18S rRNA (15).

FIG. 2.

C. serpentis (guttata) (AF151376) 18S rRNA gene (1,743 bp).

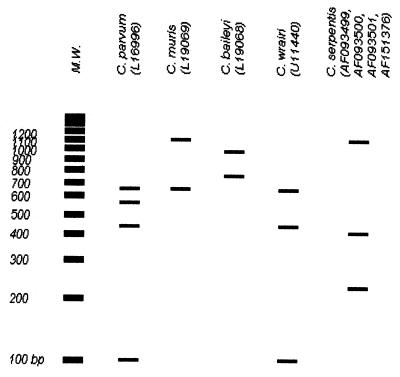

Sequence analysis of the ca. 1,750-bp product amplified from gDNA extracted from both the gastric lavage and gastric mucosa revealed a high degree of nucleotide sequence homology to 18S rRNA genes of other Cryptosporidium species (Table 2). There is an SspI restriction site at position 223 (Fig. 3) of C. serpentis, which is not present at this position in C. parvum, Cryptosporidium muris, C. wrairi, or Cryptosporidium baileyi. Recently, GenBank has accepted sequences of the 18S rRNA gene of C. serpentis (accession no. AF093499, AF093500, AF093501, and AF093502 [28]). A multiple alignment of our sequence against those of Xiao et al. (28) reveals that our C. serpentis (guttata) sequence is identical with the C. serpentis (snake) sequence of Xiao et al. (Table 3). Initially, a single amplicon was sequenced and revealed three apparent nucleotide discrepancies with the C. serpentis (snake) sequence of Xiao et al., at positions 998, 1156, and 1477. However, confirmation of this sequence by the subsequent analysis of three additional amplicons disputed these substitutions and produced three identical sequences, each of which was 100% homologous to the C. serpentis (snake) sequence of Xiao et al. An SspI restriction site discovered at position 223 of our sequence, a site which is not present at this position in C. parvum, C. muris, C. wrairi, or C. baileyi, is conserved in all three sequences of Xiao et al. (28).

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide sequence homologya in the 18S rRNA gene for four species of Cryptosporidium to C. serpentis (guttata)

| Organism | Accession no. | % Homology |

|---|---|---|

| C. serpentis | AF151376 | 100 |

| C. muris | L19069 | 95 |

| C. parvum | L16996 | 94 |

| C. baileyi | L19068 | 94 |

| C. wrairi | U11440 | 94 |

With BLAST (1).

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation showing the resulting fragments of an SspI-SpeI digestion of the 18S rRNA gene in Cryptosporidium spp.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide substitutions and their positions on the 18S rRNA gene from multiple alignment of C. serpentis (guttata) versus three other strains of C. serpentis

| Position from 5′ | Nucleotideb in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. serpentis guttata (AF151376) | C. serpentis (Snake) (AF093499) | C. serpentis (Savanna monitor) (AF093500) | C. serpentis (Savanna monitor) (AF093501) | |

| 60 | T | T | [C] | T |

| 369 | A | A | [G] | A |

| 558 | T | T | [C] | T |

| 683 | T | T | [C] | T |

| 698 | A | A | [G] | [G] |

| 1674 | G | G | [A] | [A] |

With CLUSTAL W (25).

Substitutions are in brackets.

DISCUSSION

Clinically, Cryptosporidium was high on the list of differential diagnoses for this animal. The positive acid-fast staining and EIA results supported this diagnosis. The initial PCR to screen for Cryptosporidium spp. provided the most definitive evidence.

The histologic findings also were consistent with cryptosporidiosis, and these organisms are most likely C. serpentis, based on location (i.e., gastric). This is in agreement with previously reported data on Cryptosporidium in snakes (2, 5). The positive EIA results on the feces and the large-intestine mucosa were unexpected. These positive results were possibly from the passage of antigenic remnants rather than the actual presence of the organism (7, 9, 10, 12). Other possibilities which might explain the disparity between EIA and PCR include the inhibition of PCR by contaminants coextracted with the gDNA (19, 24) and the sensitivity of PCR. Although the limits of detection for the PCR were not determined in this case, previous studies utilizing primers targeting the 18S rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium have been capable of detecting as little as one oocyst by two rounds of amplification without subsequent hybridization (18). Addition of 10 to 20 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml to PCR mixtures, in an attempt to relieve any inhibition, had no effect.

The changes observed in the liver were most likely reflective of the anorexia observed clinically.

Our assumption that this organism was C. serpentis was not verifiable by the PCR and RFLP protocol previously described (3, 13, 14). In fact, Leng et al. (15) recently used PCR-RFLP to differentiate C. parvum, C. muris, and C. baileyi, and based on their choice of restriction enzymes, our initial evaluation of the genomic DNA extracted from gastric lavage and intestinal membranous scrapings with PCR-RFLP were suggestive of C. muris (Fig. 1). This was of particular interest considering the low mortality, despite the high morbidity, of snakes afflicted with cryptosporidiosis and especially given that their natural diet includes mice. Additionally, there remains some argument as to whether all Cryptosporidium organisms actually represent different strains of a single species (26). We chose to sequence the targeted fragment because there is a high degree of sequence homology in the 18S rRNA gene among different isolates and species of Cryptosporidium. Based on our findings, we conclude that the organism identified in this snake is C. serpentis. Further investigation of available 18S rRNA gene sequences for Cryptosporidium spp. showed that coupling digestion by SspI with SpeI instead of VspI enables the differentiation of C. parvum (bovine) from C. wrairi. An SpeI restriction site at position 889 bp of the 18S rRNA gene of C. wrairi is not present at this locus in any isolate of C. parvum sequenced to date.

Conclusion.

Identification of Cryptosporidium organisms to species level is necessary in order to achieve a complete understanding of the significance of these organisms as environmental contaminants. Further investigation is needed to develop an assay that is capable of identifying Cryptosporidium to species level. Significant steps toward this goal have been made. The initial discovery by Leng et al. (15) of combining PCR and enzymatic digestion of the 18S rRNA gene with VspI and DraI allowed identification of three species of Cryptosporidium: C. parvum, C. muris, and C. baileyi. The use of VspI and DraI, however, fails to distinguish C. serpentis from C. muris because both contain the VspI recognition sequence at the same position on the 18S rRNA gene. Likewise, neither the use of VspI and DraI by Leng et al. nor the recent combination of VspI and SspI by Xiao et al. (28) can distinguish the bovine isolates of C. parvum from C. wrairi. After evaluation of our sequence and all available Cryptosporidium 18S rRNA gene sequences, we determined that digestion of the 18S rRNA gene with the restriction enzymes SspI and SpeI enables the differentiation of the five presently sequenced species of Cryptosporidium: C. parvum, C. muris, C. baileyi, C. wrairi, and C. serpentis (Fig. 3) at this locus. Unlike the method of Xiao et al., the use of SpeI enables the distinction between C. wrairi and the bovine strains of C. parvum. Our work on the infectivity and viability of cryptosporidiosis is ongoing. Presently, we are targeting other loci for comparative analysis while characterizing the 18S rRNA genes of other species of Cryptosporidium.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lou Meng and Lin Lin from the University of Miami School of Medicine Research Molecular Pathology Laboratory and Anton Zimmerman for their expert advice during molecular trials. We also thank the DNA Synthesis Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Miami School of Medicine, for preparation of primers and assistance with the sequencing protocol. Finally, our thanks goes to the Division of Comparative Pathology at the University of Miami School of Medicine for laboratory and equipment access.

This study was made possible by National Institutes of Health training grant T32-RR07057.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Bird R G, Smith M D. Cryptosporidiosis in man: parasite life cycle and fine structural pathology. J Pathol. 1980;132:217–233. doi: 10.1002/path.1711320304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brownstein D G, Strandberg J D, Montali R J, Bush M, Fortner J. Cryptosporidium in snakes with hypertrophic gastritis. Vet Pathol. 1977;14:606–617. doi: 10.1177/030098587701400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Burks, C., et al. 1996. Unpublished data.

- 3.Cai J, Collin M D, McDonald V, Thompson D E. PCR cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the 18S rRNA genes and internal transcribed spacer I of the protozoan parasites Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium muris. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1992;1131:317–320. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90032-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carraway M, Tzipori S, Widmer G. Identification of genetic heterogeneity in the Cryptosporidium parvum ribosomal repeat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:712–716. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.712-716.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cranfield M R, Graczyk T K. Cryptosporidiosis. In: Mader D R, editor. Reptile medicine and surgery. W. B. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Co.; 1996. pp. 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Current W L, Garcia L S. Cryptosporidiosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:325. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dagan R, Fraser D, El-On J, Kassis I, Deckelbaum R, Turner S. Evaluation of an enzyme immunoassay for the detection of Cryptosporidium spp. in stool specimens from infants and young children in field studies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:134–138. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fayer R, Ungar B L P. Cryptosporidium spp. and cryptosporidiosis. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:458–483. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.458-483.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia L S, Brewer T S, Bruckner D A. Fluorescence detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in human fecal specimens by using monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:119–121. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.1.119-121.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia L S, Shum A C, Bruckner D A. Evaluation of new monoclonal antibody combination reagent for direct fluorescence detection of Giardia cysts and Cryptosporidium oocysts in human fecal specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3255–3257. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3255-3257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graczyk T K, Balazs G H, Work T, Aguirre A A, Ellis D M, Murakawa S K K, Morris R. Cryptosporidium sp. infections in green turtles, Chelonia mydas, as a potential source of marine waterborne oocysts in the Hawaiian Islands. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2925–2927. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2925-2927.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graczyk T K, Cranfield M R, Fayer R. Evaluation of commercial enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) test kits for detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts of species other than Cryptosporidium parvum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:274–279. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson A M, Fielke R, Lumb R, Baverstock P R. Phylogenetic relationships of Cryptosporidium determined by ribosomal RNA sequence comparison. Int J Parasitol. 1990;20:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(90)90093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilani R T, Wenman W M. Geographical variation in 18S rRNA sequence of Cryptosporidium parvum. Int J Parasitol. 1994;24:303–306. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leng X, Mosier A D, Oberst R D. Differentiation of Cryptosporidium parvum, C. muris and C. baileyi by PCR-RFLP analysis of the 18S rRNA gene. Vet Parasitol. 1996;62:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine N D. Some correlations of coccidian (apicomplexa:protozoa) nomenclature. J Parasitol. 1980;66:830–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercado R, Santander F. Size of Cryptosporidium oocysts excreted by symptomatic children of Santiago, Chile. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1995;37:473–474. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651995000500016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Pieniazek, N. J., et al. 1993. Unpublished data.

- 18.Rochelle P A, De Leon R, Stewart M H, Wolfe R L. Comparison of primers and optimization of PCR conditions for detection of Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia in water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:106–114. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.106-114.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rochelle P A, Will J A K, Fry J C, Jenkins G J S, Parkes R J, Turley C M, Weightman A J. Extraction and amplification of 16S rRNA genes from deep marine sediments and seawater to assess bacterial community diversity. In: Trevors J T, van Elsas J D, editors. Nucleic acids in the environment: methods and applications. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheehan D C, Hrapchak B B. Theory and Practice of Histotechnology. 2nd ed. St. Louis: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1980. pp. 235–237. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slavin D. Cryptosporidium meleagridis (sp. nov.) J Comp Pathol. 1955;65:262–270. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1742(55)80025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solo-Gabriele H, Neumeister S. U.S. outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1996;88:76–86. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solo-Gabriele H M, Miller D L, Montas L. Proceedings of the Florida Section American Water Works Association Annual Conference. Vol. 6. 1998. Bottom sediments, a reservoir of Cryptosporidium oocysts? pp. 1–5. Orlando, Fla. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tebbe C C, Vahjen W. Interference of humic acids and DNA extracted directly from soil in detection and transformation of recombinant DNA from bacteria and a yeast. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2657–2665. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2657-2665.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzipori S, Angus K W, Campbell I, Gray E W. Cryptosporidium: evidence for a single-species genus. Infect Immun. 1980;30:884–886. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.3.884-886.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Method 1622: Cryptosporidium in water by filtration/IMS/FA and viability by DAPI/PI. EPA821-D-97-001 (Draft). Washington, D.C.: Office of Water, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao, L., et al. 1998. Unpublished data.