Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine how maintenance session attendance and 6-month weight loss (WL) goal achievement impacted 12-month 5% WL success in older adults participating in a community-based Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) lifestyle intervention.

Methods

Data were combined from 2 community trials that delivered the 12-month DPP-based Group Lifestyle Balance (GLB) to overweight/obese adults (mean age = 62 years, 76% women) with prediabetes and/or metabolic syndrome. Included participants (n = 238) attended ≥4 core sessions (months 0–6) and had complete data on maintenance attendance (≥4 of 6 sessions during months 7–12) and 6- and 12-month WL (5% WL goal, yes/no). Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate the odds of 12-month 5% WL associated with maintenance attendance and 6-month WL. Associations between age (Medicare-eligible ≥65 vs <65 years) and WL and attendance were examined.

Results

Both attending ≥4 maintenance sessions and meeting the 6-month 5% WL goal increased the odds of meeting the 12-month 5% WL goal. For those not meeting the 6-month WL goal, maintenance session attendance did not improve odds of 12-month WL success. Medicare-eligible adults ≥65 years were more likely to meet the 12-month WL goal (odds ratio = 3.03, 95% CI, 1.58–5.81) versus <65 years.

Conclusions

The results of this study provide important information regarding participant attendance and WL for providers offering DPP-based lifestyle intervention programs across the country who are seeking Medicare reimbursement. Understanding Medicare reimbursement-defined success will allow these providers to focus on and develop strategies to enhance program effectiveness and sustainability.

The US Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) demonstrated that behavioral lifestyle intervention with weight loss and physical activity goals can prevent/delay the development of type 2 diabetes.1–3 Despite widespread success of the intervention across all ages, DPP participants ages 60 to 85 years exhibited greater diabetes risk reduction than participants younger than 60 years old (71% vs 58% risk reduction, respectively).4

Building on the results of the DPP clinical trial, DPP lifestyle intervention translation efforts, such as the Group Lifestyle Balance (DPP-GLB) Program, also then tested and demonstrated success in reducing weight, increasing activity levels, and modifying diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk factors in diverse community settings.5–10 Given the effectiveness of these DPP-based community lifestyle interventions and to aid in disseminating these programs, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was authorized by Congress to establish the National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP).11 The Diabetes Prevention Recognition Program (DPRP) was created to monitor delivery of the National DPP12 and collect program data, including participant weight change and session attendance, in 6-month intervals to recognize DPP programs meeting set standards.13 In 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) began reimbursing CDC-recognized programs for delivery to all fee-for-service beneficiaries ages 65 years and older with prediabetes. This CMS reimbursement structure is based on 2 parameters: session attendance (at 6 and 12 months) and 5% weight loss goal achievement at 12 months.14

The CDC-approved, CMS-reimbursable14,15 DPP-GLB lifestyle intervention program lasts 12 months and consists of 16 core sessions that comprise the intensive contact phase during the first 6 months, followed by 6 monthly maintenance sessions (months 7–12). The impact of maintenance session attendance during months 7 to 12 on meeting the 5% weight loss goal at 12 months has not been examined in lifestyle interventions either for the general adult population or in Medicare-eligible adults. This examination is important given that successful maintenance of the 5% weight loss goal at 12 months is a program requirement for CMS reimbursement and weight loss maintenance is essential for the participant to obtain long-term health benefits.16,17 The ability of providers to receive full reimbursement makes sustained delivery of programs possible, which is necessary to determine program success, increase program reach, and ensure long-term health benefits for participants.

As of April 2019, over 324,000 participants across more than 3000 organizations have participated in DPP-based lifestyle interventions.18 Yet many feasibility issues remain unanswered for community implementation of the program,19 including the impact of maintenance sessions on program success and effectiveness as well as the benefit of these programs in Medicare-eligible older versus middle-aged adults. Thus, this investigation examined the association between DPP-GLB maintenance session attendance and (1) achievement of the 5% weight loss goal at 12 months in all participants and by Medicare eligibility and (2) how this association was modified by having met the weight loss goal at 6 months. It was hypothesized that both maintenance session attendance and weight loss goal achievement at 6 months would significantly impact the weight loss goal at 12 months.

Methods

Research Design

The current investigation combined data from 2 NIH-funded intervention trials, the Healthy Lifestyle Project and the Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Change Project (PI: Dr A. Kriska) that both implemented identical DPP-based, CDC-recognized lifestyle intervention programs within senior/community centers in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. The Healthy Lifestyle Project (ie, GLB Healthy) was conducted between January 2011 and January 2014 and was shown to be both a feasible and effective DPP-based lifestyle intervention across 3 economically diverse senior/community centers (results have been previously published).8,10,20 The Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Change Project (ie, GLB Moves) began recruitment in January 2015 in various community settings and finished data collection and cleanup in 2019. GLB Moves was comprised of 2 intervention arms: one was the same DPP-based CDC-recognized lifestyle intervention program used in GLB Healthy, whereas the experimental intervention arm focused on decreasing sedentary time rather than increasing physical activity. Because the purpose of this current effort is to describe results from secondary post hoc analyses focusing on the maintenance phase of the original DPP-GLB intervention, participants in the experimental sedentary reduction intervention arm were not included.

In both trials, study staff collaborated with community partners to deliver the DPP-GLB lifestyle intervention program within similar local community center sites. Both trials employed a 6-month delayed control group intervention design in which eligible participants were randomly assigned to start the DPP-GLB lifestyle intervention immediately or were part of a 6-month waitlist control group. After 6 months, waitlisted participants received a yearlong lifestyle intervention identical to the one received by those who began immediately. This waitlist control design is appropriate for community translation research and was well received by both partner organizations and participants alike.9

Recruitment procedures were identical in both trials and included presentations at the community centers, flyers and posters, community center newsletters, and targeted direct mailing to zip codes around the community centers. The eligibility criteria were a BMI ≥24 kg/m2 (≥22 kg/m2 for Asians; both cut-points consistent with the DPP BMI eligibility criteria1) and prediabetes and/or the metabolic syndrome.21 The only eligibility criterion that differed between studies was age. Participants were eligible for GLB Healthy if they were 18 years or older, whereas for GLB Moves, they were eligible if 40 years or older. Despite this initial recruitment difference, participant age was similar in both studies: median age = 65 years (interquartile range = 54–71) in GLB Healthy, and median age = 63 years (interquartile range = 57–67) in GLB Moves.

A priori inclusion criteria for the current analyses were that participants from the 2 trials had to be recruited from and participate at a community center site (thereby excluding GLB Healthy9 enrollees from military bases and worksite settings) and take part in the CDC-recognized program with the primary goals of weight loss and moderate intensity physical activity improvement. These inclusion criteria were selected to maximize homogeneity across the 2 trials and resulted in 284 participants in the combined sample (n = 134 from GLB Healthy; n = 150 from GLB Moves; Figure 1). Additional eligibility criteria included participants with data on both maintenance session attendance and weight loss at 6 and 12 months. Only participants who received a sufficient “dose” of the core lifestyle intervention (ie, attending ≥4 sessions during the first 6 months13) were included in the current study sample. This is consistent with the minimum attendance requirement that CDC sets for sample inclusion and that CMS requires for potential 12-month reimbursement. Thus, the final analytic sample consisted of 238 adults (Figure 1). Research protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent before study enrollment.

Figure 1.

Recruitment, enrollment, and study participation flow chart in a community-based Diabetes Prevention Program Intervention, 2011 to 2019. The final analytic sample for the combined intervention trials (GLB Healthy and GLB Moves) consisted of 238 adults.

Lifestyle Intervention

The DPP-GLB lifestyle intervention curriculum used in both GLB Healthy and GLB Moves has been detailed elsewhere22,23 and is available at no cost online (www. diabetesprevention.pitt.edu). Similar to other DPP-based CDC-recognized lifestyle intervention programs, it is a 12-month, in-person, group-based program with a total of 16 core sessions and 6 maintenance sessions taught by a trained lifestyle coach. In the first 6 months of core sessions, there are 12 weekly sessions followed by 4 biweekly sessions. Months 7 to 12 consist of 6 monthly maintenance sessions.13 The main goals of the DPP-GLB lifestyle intervention were to encourage participants to increase physical activity levels to at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week and achieve and maintain a 7% weight loss in a safe and progressive manner. All lifestyle coaches in both studies completed a standardized 2-day training workshop provided by the Diabetes Prevention Support Center and recognized by the CDC.23 Group sessions were held at senior/community centers, and participants received session handouts, self-monitoring logs, and a pedometer and were weighed at each session.

Study Measures

All study measures were collected at community sites. Both clinical trials used the same standardized data collection forms and the same measures. At the initial onsite screening visits to determine eligibility, participant age, sex, employment, and other demographic characteristics were completed. Self-reported leisure physical activity levels were assessed by trained interviewers using a past-month version of the Modifiable Activity Questionnaire (MAQ),24 which has been shown to be both valid and reliable in adult populations.25,26 The MAQ assesses past-month moderate/vigorous-intensity leisure physical activities common to this study population and was used in the original DPP.24 Results from the MAQ are coded as MET-h/wk.27 Weight and height were measured at clinic assessment visits with shoes removed in light clothing using a standard protocol and a validated medical scale.

For this report, baseline weight was defined as the weight measure taken at the start of group intervention (ie, after the 6-month delay for participants randomized to that arm). Weight loss success was defined as a loss ≥5% (yes/no). The 5% weight loss goal cut-point was selected because studies have shown this amount of weight loss to be consistently associated with improved health28,29 and it is the cut-point currently used by both the CDC and CMS as the minimum weight loss goal for lifestyle intervention programs.30

Sufficient participant attendance of maintenance sessions (yes/no) was defined in accordance with CMS criteria as completing at least 4 out of 6 maintenance sessions (2 sessions during months 7–9 and 2 sessions during months 10–12).14 Attending the session in person or making up the sessions via phone or email were classified as completing a group session, but only if participants received and discussed the information with a trained lifestyle coach. This definition of attendance corresponds to the CMS maintenance session reimbursement criteria.14

Statistical Methods

Median and interquartile ranges are presented for continuous variables and frequency (%) for categorical variables. Participant baseline characteristics were compared between the 2 study cohorts using χ2 tests (or Fisher’s exact tests) for categorical variables and t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests (if nonnormally distributed) for continuous variables.

The association between maintenance session attendance (attending ≥4 sessions vs <4 sessions) and weight loss success at 12 months was assessed using multivariate logistic regression. To initially evaluate effect modification by 6-month weight loss success on this association, interaction terms were included between meeting the 5% weight loss goal at 6 months and maintenance attendance in the logistic regression models. A combination of a priori and empirically based modeling strategies was used to address potential confounders of interest for the aforementioned logistic regression models. A priori, models were constructed including several covariates (eg, education, sex, smoking, age, leisure activity at 6 months, hours per day spent watching TV, and employment). Backward selection with a significance level cut-point of P < .20 to retain covariates was used to fit the final multivariable models. This resulted in only age being retained in the model; however, sex and self-reported leisure activity at 6 months were also included in the final model, as suggested by prior literature.

Due to the importance of weight loss success at 6 months, differences in maintenance attendance across combined categories of weight loss success at 6 months (yes/no) and 12 months (yes/no) were also examined using a 4-level nominal weight loss variable with all possible combinations of success: (1) met weight loss goal at both 6 and 12 months (maintain), (2) did not meet weight loss goal at 6 months but did meet at 12 months (improve), (3) met weight loss goal at 6 but not 12 months (regress), and (4) did not meet weight loss goal at either 6 or 12 months (fail). Differences in baseline characteristics across the combined categories were assessed using χ2 tests (or Fisher’s exact tests) for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Multinomial logistic regression models were constructed to assess the association between maintenance attendance and weight loss success at 6 months (yes/no) and 12 months (yes/no) combined using the 4-level nominal weight loss success variable for combined 6- and 12-month weight loss success (defined previously as the dependent variable).

The association between age as defined by Medicare eligibility (<65 (reference), ≥65 years) and both maintenance session attendance and achieving the 5% weight loss goals at 6 and 12 months was assessed using χ2 tests. Multivariable logistic regression models were fit to assess whether meeting weight loss goals at 6 and 12 months or attending ≥4 maintenance sessions was associated with age (<65 years vs Medicare-eligible older adults: ≥65 years) after controlling for potential confounders, including sex, employment, race/ethnicity, and baseline leisure physical activity.

To ensure the estimated associations were robust, 2 sensitivity analyses were conducted. In the first, a new attendance variable for in-person attendance only versus any other contact or nonattendance was created and used in univariate and multivariate models. In the second sensitivity analysis, an interaction term between a study indicator variable (GLB Healthy or GLB Moves) and maintenance attendance was included to assess evidence of heterogeneity in the association between attendance and 12-month weight loss success between the 2 trials. All analyses were performed using SASv9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) statistical software.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the 2 studies were similar with a few exceptions. The GLB Moves relative to the GLB Healthy trial sample included a higher percentage of women (GLB Moves: 82.8%; GLB Healthy: 67.3%), higher median BMI (GLB Moves: 34.5 kg/m2; GLB Healthy: 32.6 kg/m2), larger waist circumference (GLB Moves: 43 cm; GLB Healthy: 41 cm), and fewer current smokers.

Participant baseline characteristics for the combined study sample are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants were female (75.6%), and almost half were Medicare-eligible (45.4% ≥65 years). In addition, over half of the participants earned at least a bachelor’s degree, and most self-identifed as being non-Hispanic white (89.5%). Mean baseline BMI was 33.8 kg/m2.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics for Participants Enrolled in a Community-Based Diabetes Prevention Program Lifestyle Intervention Program, 2011 to 2019 (N = 238)

| Characteristic | Baseline |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 64 (55–69) |

| Medicare-eligible, ≥65 y, n (%) | 108 (45.4) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 180 (75.6) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| ≤Some college | 109 (45.8) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 129 (54.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 33.8 (30.0–38.4) |

| Waist circumference, cm, median (IQR) | 42 (39.3–46.0) |

| MAQ, h/d spent watching TV, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) |

| MAQ, MET-h/wk leisure activity, median (IQR) | 10.5 (3.5–21.4) |

| Smoking status, n (%) current smoker | 9 (3.8) |

| Employment status, n (%) full-time/part-time | 119 (50.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) Non-Hispanic White | 213 (89.5) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; MAQ, Modifiable Activity Questionnaire; MET, metabolic equivalent task.

In all, 53.8% and 47.1% of participants met the 5% weight loss goal at 6 and 12 months, respectively. Achieving the 6-month weight loss goal was significantly associated with greater odds of meeting the 12-month weight loss goal (odds ratio [OR] = 29.2, 95% CI, 14.0–60.6).

Attendance was high, with 84% (n = 200) of participants attending at least 4 out of 6 maintenance sessions. As shown in Table 2, the odds of meeting the 12-month 5% weight loss goal were also significantly greater for those who attended ≥4 maintenance sessions compared to those who did not (OR = 6.0, 95% CI, 2.4–15.0). For the outcome, meeting the 12-month weight loss goal, there was a significant interaction (P = .05) between maintenance attendance and meeting the 5% weight loss goal at 6 months, suggesting effect modification. When stratified by achieving the 5% weight loss goal at 6 months, attending ≥4 maintenance sessions was associated with meeting the 12-month weight loss goal only in those who had also met the goal at 6 months (OR = 11.4, 95% CI, 3.2–40.7), versus those who failed to meet the weight loss goal at 6 months (OR = 1.5, 95% CI, 0.3–7.5; Table 2). Adjustment for age, sex, and leisure activity at 6 months did not have a meaningful effect on the results (Table 2).

Table 2.

Odds Ratios (95% CI) for Meeting the 5% Weight Loss Goal at 12 Months Associated With Attending ≥4 Maintenance Sessions (reference <4 sessions), Overall and Stratified by Meeting the 5% Weight Loss Goal at 6 Months, 2011 to 2019 (N = 238)

| Unadjusted ORa (95% CI) | Adjusted ORb,c (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Overall | 6.0 (2.4, 15.0)d | 6.4 (2.5, 16.5)d |

| Met 5% weight loss goal at 6 mo | 11.4 (3.2, 40.7)d | 10.9 (2.9, 41.0)d |

| Did not meet 5% weight loss goal at 6 mo | 1.5 (0.3, 7.5) | 1.6 (0.3, 8.1) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Attendance × 6-month goal status interaction P value = .05.

Adjusted for age, sex, and leisure activity at 6 months.

Attendance × 6-month goal status interaction P value = .07.

P < .001.

Figure 2 shows the combination of 5% weight loss success at both 6 and 12 months by maintenance session attendance (<4 sessions vs ≥4 sessions) with significant differences found across the combined weight loss categories (P < .001). The proportion who improved between 6 and 12 months (ie, did not meet weight loss goal at 6 months but did meet at 12) was similar (~5%) regardless of attendance. However, those who attended ≥4 maintenance sessions were more likely to maintain weight loss between 6 and 12 months (48%) compared to those who attended <4 sessions (10.5%). Additonally, the participants who attended ≥4 maintenance sessions were less likely to regress (9.5%) or fail (37.5%) than those who attended <4 sessions (23.7% and 60.5%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Distribution of combined weight loss success status at 6 and 12 months by maintenance session attendance in a community-based Diabetes Prevention Program Intervention, 2011 to 2019 (N = 238).

In an additional analysis to determine whether any demographic factors were associated with trends in weight loss success, those who maintained (age = 64.7 years ± 9.9) or improved (age = 65.8 years ± 10.6) were older than those who regressed (age = 59.1 years ± 10.0) or failed (age = 59.9 years ± 10.0; P = .002; Table 3). Participants that were not working were also more likely to maintain weight loss (63%) compared to those working full- or part-time (37%). Additional demographic differences are shown in Table 3, with some statistically significant differences but no discernable trends in weight success noted.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristic Differences Across Combined Weight Loss Success Status at 6 and 12 Months, 2011 to 2019 (N = 238)a

| Maintain |

Improve |

Regress |

Fail |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic (N = 238) | Met weight loss goal at 6 and 12 mo (n = 100) | Did not meet at 6 mo, but did meet at 12 mo (n = 12) | Met weight loss goal at 6 mo, not 12 mo (n = 28) | Did not meet weight loss goal at 6 or 12 mo (n = 98) | P value |

|

| |||||

| Age | 64.7 ± 9.9 | 65.8 ± 10.6 | 59.1 ± 10.0 | 59.9 ± 10.0 | .002 |

| Medicare-eligible, ≥65 y | 61 (61%) | 8 (66.7%) | 7 (25%) | 32 (32.7%) | <.0001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 73 (73%) | 11 (91.7%) | 18 (64.3%) | 78 (79.6%) | .0007 b |

| Male | 27 (27%) | 1 (8.3%) | 10 (35.7%) | 20 (20.4%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 93 (93%) | 12 (89.3%) | 25 (89.3%) | 83 (84.7%) | .002 b |

| Other | 7 (7%) | 0 | 3 (10.7%) | 15 (15.3%) | |

| Education | |||||

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 46 (46%) | 6 (50%) | 19 (67.9%) | 58 (59.2%) | .12 |

| ≤Some college | 54 (54%) | 6 (50%) | 9 (32.1%) | 40 (40.8%) | |

| Employment | |||||

| Full-time/part-time | 37 (37%) | 6 (50%) | 19 (67.9%) | 57 (58.2%) | .005 |

| Other | 63 (63%) | 6 (50%) | 9 (32.1%) | 41 (41.8%) | |

| MAQ, h/d spent watching TV at baseline | 3.5 ± 2.2 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 3.4 ± 3.2 | 3.1 ± 2.2 | .57 |

| MAQ, MET-h/wk baseline leisure activity | 15.2 ± 17.1 | 8.2 ± 7.5 | 21.2 ± 19.1 | 15.0 ± 14.8 | .11 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 35.1 ± 6.4 | 36.5 ± 7.5 | 33.5 ± 6.2 | 34.9 ± 6.7 | .58 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 43.4 ± 5.5 | 43.1 ± 6.3 | 42.2 ± 5.2 | 42.1 ± 5.2 | .42 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MAQ, Modifiable Activity Questionnaire; MET, metabolic equivalent task. Mean ± standard deviation (analysis of variance) or N (%; χ2) reported.

Indicates Fisher exact P value. Bolded values indicate statistically significant differences across groups.

Attending ≥4 maintenance sessions was associated with significantly higher odds of meeting the 5% weight loss goal at both 6 and 12 months (maintain) compared to not meeting the goal at either 6 or 12 months (fail; OR = 7.4, 95% CI, 2.4–22.2; Table 4). Adjustment for age, sex, and leisure activity at 6 months yieled similar results such that attending ≥4 maintenance group sessions in the last 6 months of the intervention was positively associated with maintaining the weight loss goal at 6 and 12 months. Attending ≥4 maintenance sessions was not signficantly associated with achieving the weight loss goal at 12 months if it was not previously met at 6 months (improve; OR = 1.5, 95% CI, 0.3–7.5; Table 4).

Table 4.

Odds Ratios (95% CI) for Weight Loss Success Combined Categoriesa at 6 and 12 Months Associated With Attending ≥4 Maintenance Sessions (reference <4 sessions), 2011 to 2019 (N = 238)

| Weight loss success categories | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Maintain | 7.4 (2.4, 22.2)c | 9.3 (2.9, 30.3)c |

| Improve | 1.5 (0.3, 7.5) | 1.3 (0.2, 8.3) |

| Regress | 0.6 (0.3, 1.6) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.6) |

| Fail | Reference | Reference |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Weight loss categories defined as: maintain = met weight loss goal at 6 and 12 months; improve = did not meet at 6 months, but did meet at 12; regress = met weight loss goal at 6 months, but not 12 months; fail = did not meet weight loss goal at 6 or 12 months.

Adjusted for age, sex, and leisure activity at 6 months.

P < .001.

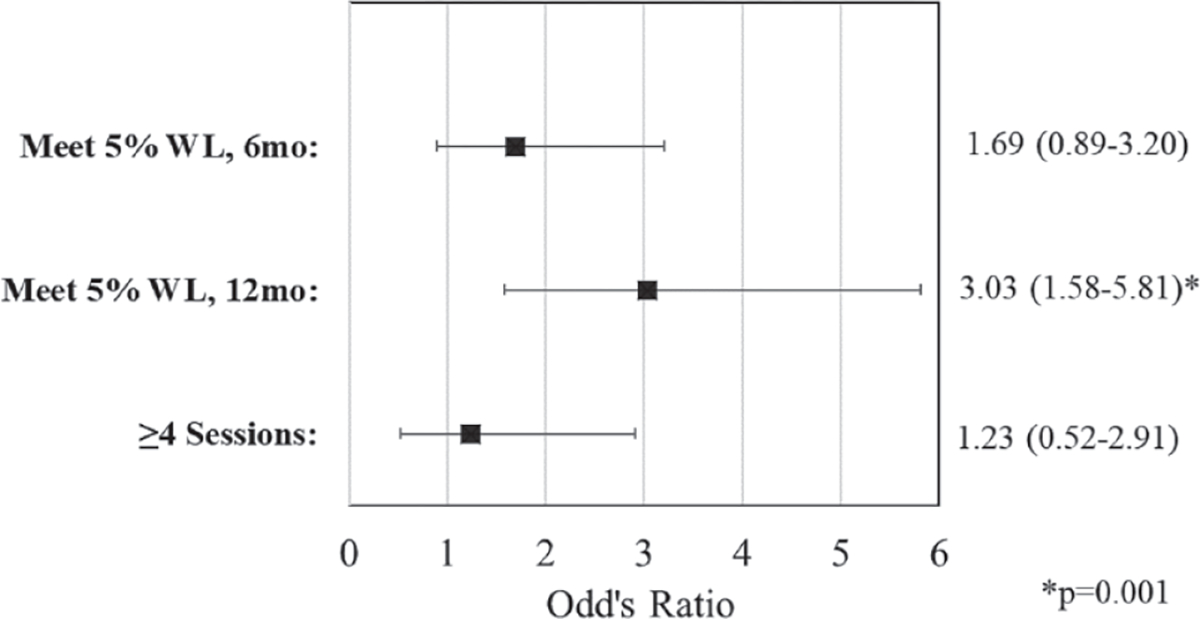

Medicare-eligible participants ages ≥65 years (n = 108) were more likely to meet the 6-month weight loss goal (63.0%) versus participants <65 years old (n = 130; 46.2%; P = .01). Medicare-eligible adults were also more likely to meet the 12-month weight loss goal (63.9%) versus participants <65 years old (33.1%; P < .0001). Maintenance attendance did not vary by age, with about 80% of both Medicare-eligible adults and those <65 years attending ≥4 maintenance sessions (overall P = .43). As shown in Figure 3, after adjusting for sex, employment, race/ethnicity, and leisure physical activity, Medicare-eligible adults were more likely to meet the 5% weight loss goal at 6 months, although this did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.69; 95% CI, 0.89–3.20; P = .11), and significantly more likely to meet the weight loss goal at 12 months (OR = 3.03; 95% CI, 1.58–5.81) compared to those <65 years old.

Figure 3.

Associations between age (Medicare-eligible older adults ≥65 vs <65 years) and meeting 6- and 12-month weight loss goals and maintenance session attendance in a community-based Diabetes Prevention Program Intervention, 2011 to 2019 (N = 238).

All models adjusted for sex, employment, race/ethnicity, and baseline leisure physical activity. Reference = <65 years. WL, weight loss.

In the sensitivity analysis using an alternative definition of attendance (ie, only in-person session attendance vs any other contact and/or nonattendance) as the independent variable in both univariate and multivariate models, the results were similar compared to the primary analysis presented previously. In addition, to determine if results varied by study, an interaction term between study cohort (GLB Moves or GLB Healthy) and maintenance attendance was examined in a univariate model with an outcome of meeting the 12-month weight loss goal and was not found to be significant (P > .2).

Discussion

This study is the first to identify a significant impact of maintenance session attendance (per CMS reimbursement requirements) on meeting the 5% weight loss goal at 12 months in a community-based DPP lifestyle intervention program. Although both the DPP clinical trial and its community translation efforts have demonstrated that earlier weight loss success was associated with maintained weight loss at follow-up, maintenance session attendance (ie, more contact in the second 6 months of the 12-month intervention) has not been examined until now. The current significant finding is in line with past research that showed that more frequent contact, in general, facilitates successful behavioral change among participants of a lifestyle intervention program.26,28 However, a caveat to this finding in the current effort was that maintenance session attendance only increased the likelihood of meeting the 12-month 5% weight loss goal in those participants who had already met the weight loss goal by 6 months.

Among participants who failed to meet the weight loss goal at 6 months, attending more maintenance sessions did not appear to significantly improve their chances of achieving weight loss success by 12 months. However, this apparent lack of association needs to be examined in a study with greater variation in maintenance session attendance. It is possible that participants who have not achieved clinically meaningful weight loss at 6 months require more tailored resources,31 or perhaps alternative therapies, in the latter part of the program to reach weight loss success by 12 months or beyond. Maintenance sessions occured monthly and focused on adherence barriers, problem-solving, managing self-defeating thoughts and social cues to prevent relapse, building social support, and enhancing motivation.22 Understanding which components of maintenance sessions are associated with weight loss success may help tailor programs to be effective in diverse populations. This is especially relevant in participants with complex health conditions,32 which likely create greater barriers to achieving their weight loss goals and thereby require multiple tailored strategies during the maintenance phase of lifestyle interventions. Successfully improving participants’ ability to achieve and maintain goals has important public health implications regarding improving health outcomes among older adults at risk for type 2 diabetes.

The results of this study also demonstrated that Medicare-eligible adults more successfully met the clinically meaningful weight loss goal at 12 months than those <65 years of age. This is in line with previous results from the DPP multicenter clinical trial itself, which showed that older adults achieved greater success with weight loss goals and reduction in diabetes incidence versus relatively younger adults.4,33 This is pertinent because almost half of US adults 65 years and older have prediabetes.34 These results provide guidance to clinical providers regarding the positive impact that participation in DPP-based lifestyle interventions can have on future health outcomes among Medicare-eligible older adults.

The current study had a few limitations. Due to high levels of session attendance, the impact of varying levels of participant attendance could not be closely examined. Both high study satisfaction (94% reported satisfied with DPP-GLB program in postintervention survey) and the convenience of community-based sites (living close to the community center was part of the recruitment strategy and study design) likely led to the high number of participants attending the majority of maintenance sessions. In addition, although the sample reflected the composition of the existing population surrounding Pittsburgh, these findings need to be replicated within more diverse Medicare-eligible populations to maximize generalizability.

The strengths of this study were many. This was the first study to investigate the impact of maintenance session attendance on achieving the program weight loss goal at 12 months overall and specifically within Medicare-eligible participants alone. Thus, these results have important public health impact as reimbursement by Medicare in these community lifestyle intervention programs is based on 2 program components at 12 months, maintenance session attendance and 5% weight loss goal acheivement. Additionally, Medicare-eligible older adults were found to be more successful with weight loss than middle-aged adults in these DPP-based community intervention programs. Finally, the reliability of these findings was demonstrated across 2 studies spanning 8 years in various community settings but both using the same DPP-based lifestyle intervention that is CDC-recognized and reimbursable by CMS.

Implications/Relevance for Diabetes Care and Education Specialists

Both attending maintenance sessions and meeting the 6-month weight loss goal in a CDC-recognized, community-based DPP lifestyle intervention were associated with greater odds of meeting the 5% weight loss goal at 12 months. These findings were stronger for Medicare-eligible older adults, offering an invaluable prevention opportunity for national Medicare-DPP providers to impact the health of US adults with prediabetes who are 65 years and older.34 Understanding Medicare reimbursement-defined success will enable providers to implement strategies that enhance program effectiveness. Thus, evaluating the effectiveness of maintenance session attendance to help participants maintain a clinically meaningful and CMS-reimbursable 5% weight loss goal has broadscale importance for both long-term participant weight loss success and sustaining program funding. In addition, more efforts are needed to find ways to help those struggling to reach the weight loss goal during the first 6 months and/or to augment the programming in the last 6 months for those who need additional help in DPP-based lifestyle intervention programs.

Acknowledgments:

We thank all of the participants in the DPP-GLB intervention, the clinic and intervention staff, including Darcy Underwood and Rebecca Meehan, and the Allegheny County Area Agencies on Aging, LifeSpan, Jewish Community Center, Kingsley Association, Vintage Center for Active Adults, Passavant Hospital Foundation, Eastern Area Adult Services, and Bayer Corporation for their collaboration on this project. This study was presented in part at the 80th American Diabetes Association Annual Conference (June 2020) and the 75th Gerontological

Funding:

This project was supported by NIH-National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R18 DK081323–04 and 5R18DK100933–04) and NIA/NIH (T32 AG000181–28).

Footnotes

Society of America Conference (November 2020). The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Jenna M. Napoleone, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Rachel G. Miller, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Susan M. Devaraj, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Bonny Rockette-Wagner, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Vincent C. Arena, Department of Biostatistics, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Elizabeth M. Venditti, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Kaye Kramer, Spark 360, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

Elsa S. Strotmeyer, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Andrea M. Kriska, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan X-R, Li G-W, Hu Y-H, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(4):537–544. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crandall J, Schade D, Ma Y, et al. The influence of age on the effects of lifestyle modification and metformin in prevention of diabetes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(10):1075–1081. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer MK, Miller RG, Siminerio LM. Evaluation of a community Diabetes Prevention Program delivered by diabetes educators in the United States: one-year follow up. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106(3):e49–e52. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma J, Yank V, Xiao L, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle intervention for weight loss into primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(2):113. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piatt GA, Seidel MC, Chen H-Y, Powell RO, Zgibor JC. Two-year results of translating the diabetes prevention program into an urban, underserved community. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(6):798–804. doi: 10.1177/0145721712458834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer MK, Vanderwood KK, Arena VC, et al. Evaluation of a diabetes prevention program lifestyle intervention in older adults: a randomized controlled study in three senior/community centers of varying socioeconomic status. Diabetes Educ. 2018;44(2):118–129. doi: 10.1177/0145721718759982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer MK, Molenaar DM, Arena VC, et al. Improving employee health: evaluation of a worksite lifestyle change program to decrease risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(3):284–291. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eaglehouse YL, Rockette-Wagner B, Kramer MK, et al. Physical activity levels in a community lifestyle intervention: a randomized trial. Transl J Am Coll Sports Med. 2016;1(5):45–51. doi: 10.1249/TJX.0000000000000004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Key national DPP milestones. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/milestones.htm

- 12.Centers for Diabetes Control and Prevention. CDC diabetes prevention recognition program. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/requirements-recognition.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fdiabetes%2Fprevention%2Flifestyle-program%2Frequirements.html

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diabetes Prevention Program. Standards and operating procedures. Accessed August 14, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/pdf/dprpstandards.pdf

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program (MDPP) expanded model. Accessed July 24, 2019. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/medicare-diabetesprevention-program/

- 15.Medicare program; revisions to payment policies under the physician fee schedule and other revisions to Part B for CY 2018; Medicare shared savings program requirements; and Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2017; 82(219):52976–53371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balk EM, Earley A, Raman G, Avendano EA, Pittas AG, Remington PL. Combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent type 2 diabetes among persons at increased risk: a systematic review for the community preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):437. doi: 10.7326/M15-0452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patnode CD, Evans CV, Senger CA, Redmond N, Lin JS. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without known cardiovascular disease risk factors. JAMA. 2017;318(2):175. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruss SM, Nhim K, Gregg E, Bell M, Luman E, Albright A. Public health approaches to type 2 diabetes prevention: the US National Diabetes Prevention Program and beyond. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(9):78. doi: 10.1007/s11892-019-1200-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritchie ND, Baucom KJW, Sauder KA. Current perspectives on the impact of the National Diabetes Prevention Program: building on successes and overcoming challenges. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:2949–2957. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S218334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eaglehouse YL, Schafer GL, Arena VC, Kramer MK, Miller RG, Kriska AM. Impact of a community-based lifestyle intervention program on health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(8):1903–1912. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1240-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Venditti EM, Kramer MK. Necessary components for lifestyle modification interventions to reduce diabetes risk. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(2):138–146. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0256-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer MK, Kriska AM, Venditti EM, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program: a comprehensive model for prevention training and program delivery. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kriska AM, Edelstein SL, Hamman RF, et al. Physical activity in individuals at risk for diabetes: diabetes Prevention Program. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(5):826–832. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000218138.91812.f9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kriska AM, Knowler WC, LaPorte RE, et al. Development of questionnaire to examine relationship of physical activity and diabetes in Pima Indians. Diabetes Care. 1990;13(4):401–411. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.4.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulz LO, Harper IT, Smith CJ, Kriska AM, Ravussin E. Energy intake and physical activity in Pima Indians: comparison with energy expenditure measured by doubly-labeled water. Obes Res. 1994;2(6):541–548. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kriska A Modifiable activity questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(6):73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein S, Burke LE, Bray GA, et al. Clinical implications of obesity with specific focus on cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2004;110(18):2952–2967. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145546.97738.1E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein DJ. Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992;16(6):397–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ely EK, Gruss SM, Luman ET, et al. A national effort to prevent type 2 diabetes: participant-level evaluation of CDC’s National Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(10):1331–1341. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venditti EM, Wylie-Rosett J, Delahanty LM, et al. Short and long-term lifestyle coaching approaches used to address diverse participant barriers to weight loss and physical activity adherence. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magnan EM, Palta M, Mahoney JE, et al. The relationship of individual comorbid chronic conditions to diabetes care quality. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3(1):e000080. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, et al. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004;12(9):1426–1434. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Diabetes Control and Prevention. 2020 national diabetes statistics report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2020. Accessed: April 29, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf [Google Scholar]