Abstract

Background:

The orthopaedic surgery residency program website represents a recruitment tool that can be used to demonstrate a program’s commitment to diversity and inclusion to prospective applicants. The authors assessed how orthopaedic surgery residency programs demonstrated diversity and inclusion on their program websites and whether this varied based on National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding, top-40 medical school affiliation, university affiliation, program size, or geographic region.

Methods:

The authors evaluated 187 orthopaedic surgery residency program websites for the presence of 12 elements that represented program commitment to diversity and inclusion values, based on prior work and ACGME recommendations. Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess whether NIH funding and other program characteristics were associated with commitment to diversity and inclusion on affiliated residency websites.

Results:

Orthopaedic surgery residency websites included a mean of 4.9 ± 2.1 diversity and inclusion elements, with 21% (40/187) featuring a majority (7+) of elements. Top 40 NIH funded programs (5.4 ± 2.0) did not have significantly higher website diversity scores when compared with nontop-40 programs (4.8 ± 2.1) (P = 0.250). University-based or affiliated programs (5.2 ± 2.0) had higher diversity scores when compared with community-based programs (3.6 ± 2.2) (P = 0.003).

Conclusions:

Most orthopaedic surgery residency websites contained fewer than half of the diversity and inclusion elements studied, suggesting opportunities for further commitment to diversity and inclusion. Inclusion of diversity initiatives on program websites may attract more diverse applicants and help address gender and racial or ethnic disparities in orthopaedic surgery.

Level of Evidence:

Level V

Keywords: diversity, inclusion, residency, orthopaedic surgery, website

INTRODUCTION

A diverse physician workforce is critical to the future of orthopaedic surgery. Despite overwhelming evidence demonstrating the benefits of a more diverse and inclusive workforce, orthopaedic surgery residencies have less gender, racial, and ethnic diversity when compared with other specialties and a decreasing rate of minoritized representation over the past decade.1 In recent years, there have been several diversity and inclusion initiatives launched in order to make orthopaedic surgery, and medicine as a whole, more diverse.2 The National Institutes of Health (NIH), the largest biomedical research agency in the world, has positioned itself as a strong advocate for diversity in medicine. In 1993, the NIH Revitalization Act was passed with an aim of diversifying clinical research by prioritizing the inclusion of women and minoritized groups.3 Since then, the NIH has launched a Scientific Workforce Diversity office in an effort to diversify the national scientific workforce and to expand recruitment and retention.4 The NIH has developed a broad definition of diversity by encouraging institutions to diversify their student and faculty populations to enhance the participation of individuals from groups identified as underrepresented in the biomedical, clinical, behavioral, and social sciences, such as 1) individuals from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, 2) individuals with disabilities, and 3) individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds.5 The NIH diversity goals have been mirrored at medical institutions around the country, with many institutions launching their own diversity and inclusion initiatives to better align with the diversity and inclusion policies advocated by the NIH.6,7

The primary mechanism by which the NIH and orthopaedic surgery-specific diversity and inclusion initiatives seek to address the lack of diversity in orthopaedic surgery departments is to recruit more diverse applicants. When orthopaedic surgery residency program directors were asked about barriers to increasing diversity in their programs, a frequently perceived barrier was “a lack of minority applicants applying to our program,” indicating that residency programs should target strategies for attracting more diverse applicants.8 One recruitment tool that residency programs can use to convey their commitment to diversity and inclusion to applicants is their residency program website. For example, listing additional financial resources available to trainees may attract candidates from disadvantaged backgrounds who are worried about student loans and debt, which have been associated with decreased trainee satisfaction.9 Residency applicants across several specialties have consistently listed the residency program website as an important factor used when deciding where to apply.10–13 Additionally, residency program website content has the potential to align with NIH goals regarding the use of the internet and social media to advance diversity and inclusion initiatives by publicly acknowledging diversity and inclusion elements in an effort to attract a more diverse applicant pool.14

The purpose of this study was to assess how orthopaedic surgery residency programs demonstrate commitment to diversity and inclusion on their program websites. The authors answered the following questions: 1) Do orthopaedic departments with the highest NIH funding align themselves with NIH diversity and inclusion goals by featuring more diversity and inclusion elements on their program websites? 2) Does the number of diversity and inclusion elements on program websites vary by top-40 medical school affiliation, university affiliation, program size, or geographic region? The authors hypothesized that orthopaedic surgery residency programs that received greater funding from the NIH would demonstrate more diversity and inclusion elements on their residency program websites when compared with lesser funded programs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was deemed exempt from institutional review board approval because all data obtained for this study were publicly available.

Program Eligibility

The Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database (FREIDA) was used to obtain a list of all orthopaedic surgery residency programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). There were 197 programs listed; however, eight military-based programs were excluded because of restrictions on the type of information that can be posted on government websites. Additionally, two residency programs did not have a functional website. Content analysis was completed for the remaining 187 orthopaedic surgery residency program websites from March 1, 2021, to March 31, 2021. All websites were accessed and evaluated by two authors independently (SC and MX), and a Kappa coefficient was used to calculate interrater agreement. Disputes between raters were marked and subsequently resolved after deliberation between the two independent reviewers. There was high interobserver reliability, with 92% agreement and a Kappa coefficient of 0.846.

Diversity Criteria

All program websites were evaluated for the presence of 12 criteria that demonstrate program commitment to diversity and inclusion (Table 1). Eight of the criteria were utilized in a recent study examining the presence of diversity elements on general surgery residency program websites.15 These criteria include the following: nondiscrimination statement, diversity and inclusion message, community resources, extended faculty biographies, extended resident biographies, faculty photos, resident photos, and additional financial resources for trainees. The four remaining criteria were based on updated ACGME guidelines recommending that residency programs better emphasize wellness, mental health, health disparities, and a diverse and inclusive workforce.16 These criteria include wellness resources, mental health resources, health disparities and community engagement, and a diversity council. Each of the 12 criteria in this study represents one component of a program’s commitment to diversity and inclusion. The presence of even one of the 12 analyzed criteria may help to shape an applicant’s views regarding program commitment to diversity and inclusion.1,2,17 The authors therefore deemed a difference of at least one criteria as meaningful.

Table 1.

Definition of diversity and inclusion elements investigated for inclusion into orthopaedic surgery residency program websites

| Diversity and inclusion element | Definition of element |

|---|---|

| Nondiscrimination statement | Equal opportunity or nondiscrimination statement |

| Diversity and inclusion message | Individualized message from program was separate from nondiscrimination statement regarding diversity |

| Community resources | Material about community resources, demographics, or diverse groups |

| Extended faculty biographies | Faculty biography includes personal information about interests or background |

| Extended resident biographies | Resident biography includes personal information about interests or background |

| Faculty photos | Individual photos of each faculty member |

| Resident photos | Individual photos of each current resident |

| Additional financial resources for trainees | Program details resources for financial assistance available for residents |

| Wellness resources | Wellness resources available for residents |

| Mental health resources | Mental health/counseling resources available for residents |

| Health disparities/community engagement | Community engagement initiatives aimed at addressing health disparities available for residents |

| Diversity council | Council committed to diversity and inclusion consisting at least partially of residents |

Data Collection

Programs earned a score of +1 for each diversity and inclusion element that was present and a score of 0 for each element that was absent. After data collection was complete, the total number of diversity elements was calculated for each residency program, with a maximum of 12 diversity and inclusion elements and a minimum of 0. Programs scored (+1) for the presence of a diversity and inclusion element if the criteria was satisfied either on the residency website or if there was a direct link to the departmental website of the associated academic institution that contained the necessary information, which is consistent with previous methodology.18 For programs where some but not all residents and faculty had extended biographies or photos, the program scored +1 for the applicable diversity element if more than 50% of eligible residents and faculty had biographies and photos.

Statistical Analysis

Residency programs were stratified based on NIH departmental funding, top-40 medical school affiliation, university affiliation, program size, and geographic location for statistical comparison. With regard to funding, the authors identified the top 40 programs in NIH orthopaedic funding in 2019 using data released by the Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research.19 The top 40 NIH-funded programs were used as a cutoff for this study based on previous research examining the impact of NIH funding on various residency outcomes.20–22 For top-40 medical school affiliation, the programs that were affiliated with medical schools in the top 40 of the US News and World Report “Best Research” rankings in 2019 were identified.23 For university affiliation, programs were divided into two categories: university-based or university-affiliated versus community-based. For size, programs were divided into four groups based on total number of residents: 15 or fewer, 16 to 25, 26 to 35, and 36 or more. For geographic location, programs were divided into four groups, Midwest, Northeast, South, and West, based on regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted for program funding, top-40 medical school affiliation, and university affiliation stratifications. Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted for program size and geographic region stratifications. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 26.0.0.1. The Bonferroni correction (0.05/5) was used to define statistical significance at P < 0.01 because of the increased risk of a type 1 error when performing Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Because data were obtained from all available orthopaedic surgery residency program websites, no sample size calculation was performed.

RESULTS

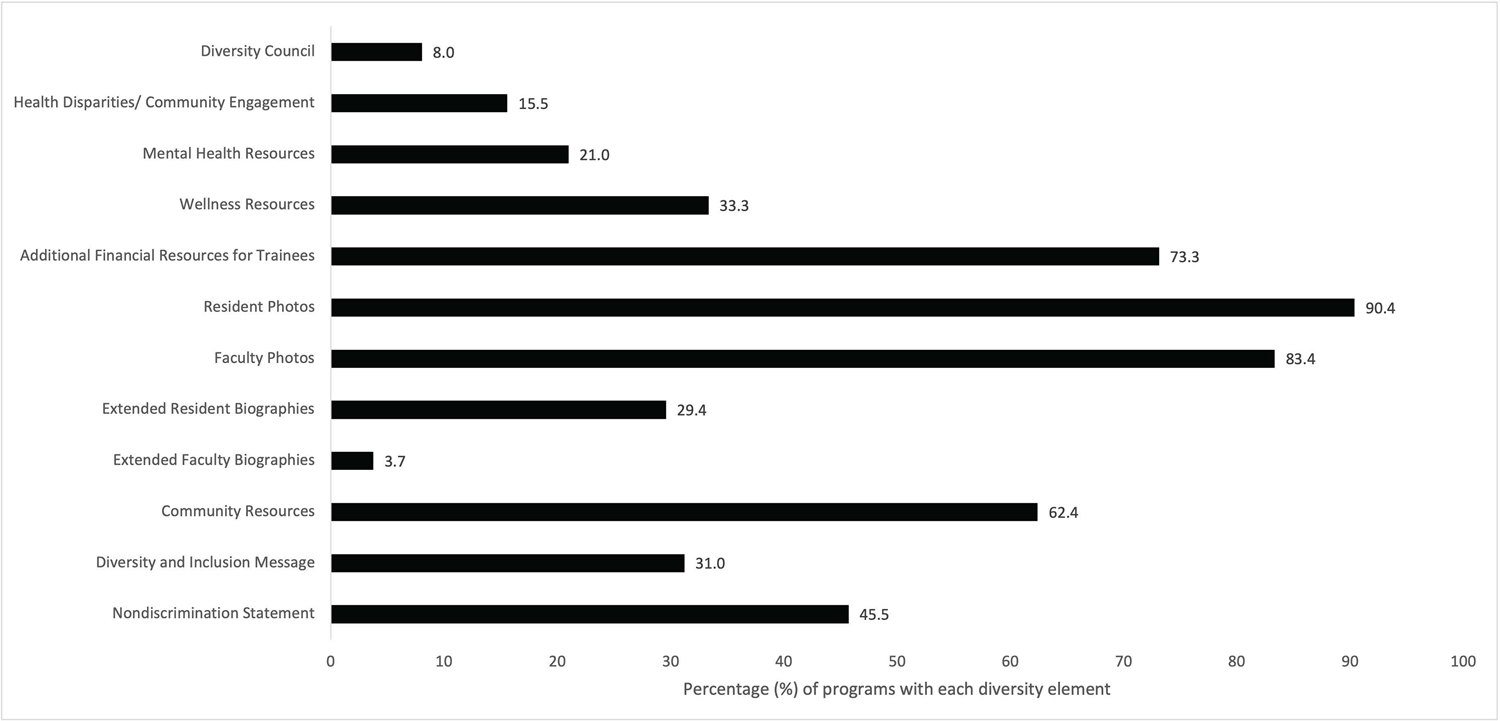

The average size of the orthopaedic surgery residency programs that were analyzed in this study was 23.1 ± 9.8 residents. The majority of programs (160/187, 85.6%) were university-based or affiliated as opposed to community-based. Further details about geographic locations of programs that were studied are listed in Table 2. Program websites included a mean ± standard deviation of 4.9 ± 2.1 diversity elements. Nearly 25% (44/187) of programs featured four diversity elements, the most common diversity score, and more than 20% (40/187) of programs featured more than half (seven or more) of all diversity elements evaluated in this study (Figure 1). The most common diversity elements included on orthopaedic surgery residency program websites were resident photos (169/187, 90.4%), faculty photos (156/187, 83.4%), and additional financial resources for trainees (137/187, 73.3%). The least common diversity elements featured included extended faculty biographies (7/187, 3.7%), information about a diversity council (15/187, 8.0%), and health disparities or community engagement opportunities for residents (29/187, 15.5%) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Stratified analysis comparing website diversity content based on National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding, Top-40 medical school affiliation, university affiliation, size, and geographic region

| Program characteristic | Number of programs | Diversity score mean (SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| NIH orthopaedic funding | 0.2501 | ||

| Top 40 | 40 | 5.4 (2.0) | |

| Not top 40 | 147 | 4.8 (2.1) | |

| Top 40 US News and World Report23 medical schools | 0.0147 | ||

| Top 40* | 42 | 5.7 (2.2) | |

| Not top 40 | 145 | 4.7 (2.0) | |

| Affiliation | 0.0002 | ||

| University-based or affiliated | 160 | 5.2 (2.0) | |

| Community-based | 27 | 3.6 (2.2) | |

| Program Size | 0.0157 | ||

| 10 to 15 | 57 | 4.3 (2.2) | |

| 16 to 25 | 80 | 5.0 (1.8) | |

| 26 to 35 | 34 | 5.5 (1.9) | |

| 36+ | 16 | 5.8 (2.2) | |

| Geographic region | 0.3866 | ||

| Northeast | 56 | 4.7 (2.3) | |

| South | 50 | 5.4 (2.1) | |

| Midwest | 54 | 4.8 (2.0) | |

| West | 27 | 4.9 (1.5) | |

NIH, National Institutes of Health; SD, standard deviation

3 medical schools were tied for the 40th position in the US News and World Report23 rankings

Figure 1.

Percentage of orthopaedic surgery residency programs with each number of diversity elements. Of the 12 diversity elements studied, residency program websites showcased a mean of 4.92 diversity elements.

Figure 2.

Percentage of orthopaedic surgery residency programs that display each diversity element on their website (n = 187 programs). Programs most commonly featured resident and faculty photos as well as additional financial resources for trainees.

The primary analysis indicated that top 40 NIH-funded programs (5.4 ± 2.0) did not demonstrate more diversity and inclusion elements on residency program websites when compared with those that were not top-40 programs (4.8 ± 2.1) (P = 0.250). Secondary analyses indicated no differences in diversity scores when comparing residency programs based on top-40 medical school affiliation, size, or geographic location. However, when stratifying programs by university affiliation, university-based or affiliated programs (5.2 ± 2.0) had higher diversity scores when compared with community-based programs (3.6 ± 2.2) (P = 0.003) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrated that most orthopaedic surgery residency program websites contained fewer than half of the 12 diversity and inclusion elements, with only 21% (40/187) of programs featuring seven or more diversity and inclusion elements on their residency program websites. There were infrequent nondiscrimination statements (85/187, 45.5%), diversity and inclusion messages (58/187, 31.0%), and extended faculty or resident biographies (7/187, 3.7% and 55/187, 29.4%, respectively), which represented potential opportunities for programs to demonstrate greater commitment to diversity and inclusion while attracting more diverse candidates. Of the program characteristics that were analyzed, only a university-based rather than community-based affiliation was associated with greater diversity and inclusion elements on program websites. Incorporating the diversity and inclusion elements included in this study onto program websites could aid in recruiting more diverse applicants and better align residency program missions with NIH diversity and inclusion goals.

A renewed emphasis on diversity and inclusion among residency programs may help to address racial and gender disparities that currently exist in orthopaedic surgery. In 2011, an analysis of diversity trends in orthopaedic surgery resulted in the suggestion that orthopaedic surgery departments should “make the achievement of diversity an institutional goal for the department, and then work toward that goal.”24 However, nearly 10 years later, orthopaedic surgery residency programs continue to have low rates of women and minoritized residents compared with other specialties.1 In fact, minoritized representation among orthopaedic surgery residents decreased by an average of 3.85% per year from 2006 to 2015.1 Changing the applicant-facing features of the program such as the residency website is one way to accomplish this goal. A strong commitment to diversity and inclusion on residency program websites could help recruit more diverse applicants, with previous reports indicating that female and underrepresented minoritized applicants, in particular, seek out diverse programs during the residency application process.17,25,26 The ability of the residency program website to reflect a strong commitment to diversity and inclusion by the program is more important now than ever as the frequency of virtual interviews increase.27 A shift to virtual recruitment events has left applicants with fewer opportunities for in-person interactions that can help to determine program culture, which applicants value when proceeding through the residency application process but is often absent from program websites.28

As the leading governmental supporter of funding for biomedical research in the United States, the NIH is uniquely positioned to influence the diversity and inclusion landscape across graduate medical education. Previous research indicates that the medical community within the United States often replicates the policies and initiatives advocated for by the NIH, with many medical schools and hospital systems using NIH’s approach to diversity as a model to guide their own diversity efforts.6,7 Recently, the NIH has taken their support for diversity and inclusion initiatives online, with the release of the interactive NIH Scientific Workforce Diversity Toolkit, creation of a Scientific Workforce Diversity blog, and social media engagement promoting the most up-to-date diversity and inclusion publications.4,5 Residency programs who wish to align themselves with the diversity and inclusion goals laid out by the NIH can use the residency program website as a tool to demonstrate their own commitment to diversity and inclusion online. The results of this study suggest several small changes that can be implemented on residency program websites to demonstrate a greater commitment to diversity and inclusion. For example, residency program websites can display clear inclusion statements, which can be incorporated into welcome letters from program directors that are found on nearly all program websites, addressing all three facets of the NIH’s definition of diversity: 1) individuals from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups 2) individuals with disabilities and 3) individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds. The addition of an inclusion statement to the residency program website would require low time investment but could alter applicants’ perceptions of the residency program.17,26

Limitations and Future Perspectives

Several limitations to this study exist. First, there is insufficient public information about the breakdown of residency applicants by race, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status to determine whether there is an association between diversity scores on residency program websites and diversity of program applicants. Further study is necessary to determine whether a causal effect exists between demonstrated commitment to diversity and inclusion on program websites and increasingly diverse applicants and matched residents; however, previous research indicates concordance between the number of minoritized faculty and number of minoritized residents, which indicates that emphasizing program commitment to diversity may help attract diverse applicants.8 Another limitation is that the authors of this study were unable to assess diversity and inclusion element quality. The binary scoring system is consistent with previous studies using residency program website content analysis, but the inclusion of higher quality diversity and inclusion elements (e.g., resident testimonies) is likely to have a greater impact than lower quality elements.15,18,28–30 Although the 12 diversity and inclusion elements included are not a validated measure of program commitment to diversity and inclusion, these criteria have been utilized previously and are based on updated ACGME guidelines regarding residency program diversity and inclusion.15,16 Finally, orthopaedic NIH funding is dependent on faculty submitting and receiving grants. There may be variability in funding to orthopaedic departments on a yearly basis that was not captured in this cross-sectional study.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a large potential for orthopaedic surgery residency programs to use their residency website to further their commitment to diversity and inclusion initiatives. Incorporating the diversity and inclusion elements that have been analyzed in this study represents a low-burden way to signal a greater commitment to diversity that could help programs recruit more diverse applicants. The NIH has served as a model in the medical community for launching diversity initiatives in the past, and their use of the internet as a diversity and inclusion tool could prompt orthopaedic surgery departments to similarly harness the power of the internet to demonstrate their commitment to diversity and inclusion.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosures: This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health K23AR073307-01 and Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation Mentored Clinician Scientist Grant #19-064 to Dr. Kamal. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Poon S, Kiridly D, Mutawakkil M, et al. Current trends in sex, race, and ethnic diversity in orthopaedic surgery residency. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019; 27(16):e725–e733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Day MA, Owens JM, Caldwell LS. Breaking barriers: a brief overview of diversity in orthopedic surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 2019; 39(1):1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institutes of Health. Policy & Compliance. [NIH web site]. 2020. Available at https://grants.nih.gov/policy/index.htm. Accessed February 13, 2021.

- 4.National Institutes of Health. Scientific Workforce Diversity at NIH. [NIH web site]. 2021. Available at https://diversity.nih.gov/. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- 5.National Institutes of Health. Populations Underrepresented in the Extramural Scientific Workforce. [NIH web site]. February 7, 2020. Available at https://diversity.nih.gov/about-us/population-underrepresented Accessed June 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valantine HA, Lund PK, Gammie AE. From the NIH: a systems approach to increasing the diversity of the biomedical research workforce. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016; 15(3):fe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valantine HA. NIH’s scientific approach to inclusive excellence. FASEB J. 2020; 34(10):13085–13090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald TC, Drake LC, Replogle WH, Graves ML, Brooks JT. Barriers to increasing diversity in orthopaedics: the residency program perspective. JBJS Open Access. 2020; 5(2):e0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad FA, White AJ, Hiller KM, Amini R, Jeffe DB. An assessment of residents’ and fellows’ personal finance literacy: an unmet medical education need. Int J Med Educ. 2017; 8:192–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarman BT, Joshi ART, Trickey AW, et al. Factors and influences that determine the choices of surgery residency applicants. J Surg Educ. 2015; 72(6):e163–e171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Embi PJ, Desai S, Cooney TG. Use and utility of web-based residency program information: a survey of residency applicants. J Med Internet Res. 2003; 5(3):e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long T, Dodd S, Licatino L, Rose S. Factors important to anesthesiology residency applicants during recruitment. J Educ Perioper Med. 2017; 19(2):E604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaeta TJ, Birkhahn RH, Lamont D, Banga N, Bove JJ. Aspects of residency programs’ web sites important to student applicants. Acad Emerg Med. 2005; 12(1):89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institutes of Health. Draft Report of the Advisory Committee to the Director Working Group on Diversity in the Biomedical Research Workforce: Final Report. [NIH web site]. June 13, 2012. Available at: https://acd.od.nih.gov/documents/reports/DiversityBiomedicalResearchWorkforceReport.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Driesen AMDS, Romero Arenas MA, Arora TK, et al. Do general surgery residency program websites feature diversity? J Surg Educ. 2020; 77(6):e110–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. [ACGME web site]. 2021. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Specialties/Overview/pfcatid/14/Orthopaedic-Surgery. Accessed February 9, 2021.

- 17.Phitayakorn R, Macklin EA, Goldsmith J, Weinstein DF. Applicants’ self-reported priorities in selecting a residency program. J Grad Med Educ. 2015; 7(1):21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silvestre J, Tomlinson-Hansen S, Fosnot J, Taylor JA. Plastic surgery residency websites: a critical analysis of accessibility and content. Ann Plastic Surg. 2014; 72(3):265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research. NIH Award Rankings. [Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research web site]. February 10, 2018. Available at: http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2017/NIH_Awards_2017.htm. Accessed February 15, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wadhwa H, Shah SS, Shan J, et al. The neurosurgery applicant’s “arms race”: analysis of medical student publication in the neurosurgery residency match. J Neurosurg. 2019. Nov 1; 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan EM, Geelan-Hansen KR, Nelson KL, Dowdall JR. Examining the otolaryngology match and relationships between publications and institutional rankings. OTO Open. 2020; 4(2):2473974X20932497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobel AD, Cox RM, Ashinsky B, Eberson CP, Mulcahey MK. Analysis of factors related to the sex diversity of orthopaedic residency programs in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018; 100(11):e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U. S. News Staff. 2019 Best Grad Schools Preview: Top Medical Schools. [US News & World Report web site]. March 13, 2018. Available at www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate-schools/top-medical-schools/articles/2018-03-13/2019-best-graduate-schools-preview-top-10-medical-schools. Accessed February 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okike K, Utuk ME, White AA. Racial and ethnic diversity in orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011; 93(18):e107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yousuf SJ, Kwagyan J, Jones LS. Applicants’ choice of an ophthalmology residency program. Ophthalmology. 2013; 120(2):423–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aagaard EM, Julian K, Dedier J, et al. Factors affecting medical students’ selection of an internal medicine residency program. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005; 97(9):1264–1270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammoud MM, Standiford T, Carmody JB. Potential implications of COVID-19 for the 2020–2021 residency application cycle. JAMA. 2020; 324(1):29–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu LF, Young CA, Zamora AK, et al. Self-reported information needs of anesthesia residency applicants and analysis of applicant-related web sites resources at 131 United States training programs. Anesth Analg. 2011; 112(2):430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Svider PF, Gupta A, Johnson AP, et al. Evaluation of otolaryngology residency program websites. JAMA Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 2014; 140(10):956–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skovrlj B, Silvestre J, Ibeh C, Abbatematteo JM, Mocco J. Neurosurgery residency websites: a critical evaluation. World Neurosurg. 2015; 84(3):727–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]