Abstract

Gender-based stressors (e.g., sexism) are rooted in hegemonic masculinity, a cultural practice that subordinates women and stems from patriarchal social structures and institutions. Sexism has been increasingly documented as a key driver of mental and behavioral health issues among women, yet prior research has largely focused on heterosexual women. The current study examined associations between sexism and mental health (i.e., psychological distress) and behavioral health (i.e., alcohol- and drug-related consequences) among sexual minority women (SMW). We also examined whether these associations might be more pronounced among SMW who identify as gender minorities (e.g., gender nonbinary, genderqueer) or are masculine-presenting compared to those who identify as cisgender women or are feminine-presenting. Participants included 60 SMW (ages 19–32; 55.0% queer, 43.3% gender minority, 41.7% racial and ethnic minority) who completed self-report measures of sexism, psychological distress, and alcohol- and drug-related consequences. Results indicated that sexism was positively associated with psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, and drug-related consequences, respectively. In addition, sexism was associated with worse mental and behavioral health outcomes among SMW who identify as gender minorities or are masculine-presenting compared to SMW who identify as cisgender or are feminine-presenting. Findings provide evidence that the health impact of gender-based stressors among SMW may differ based on whether SMW identify as gender minorities and based on the extent to which SMW violate traditional gender norms.

Keywords: sexual minority women, mental and behavioral health, sexism, gender identity, gender presentation

Sexism represents a chronic and pervasive stressor in women’s lives, driving poor mental and behavioral health outcomes (Glick et al., 2000; Swim et al., 2001). Sexism refers to the systematic subordination of women through overt and subtle forms of traditional gender role stereotypes and prejudice, discrimination, demeaning and derogatory comments and behaviors, physical abuse, rape, and unwanted sexual objectification (Glick & Fiske, 2001; Oswald et al., 2019; S. Pharr, 1997; Swim et al., 2001). According to ambivalent sexism theory (Glick & Fiske, 1996, 2001), women experience multiple types of sexism, including hostile sexism and benevolent sexism. Hostile sexism refers to overtly negative beliefs about women as manipulative, as seeking to control men, and in need of domination, whereas benevolent sexism relies on paternalizing justifications of male dominance and prescribed gender roles, embraces a romanticized view of sexual relationships between men and women, and recognizes men’s dependence on women (Glick & Fiske, 1996; Salomon et al., 2020). Many women report encountering sexism at least once or twice a week (Brinkman & Rickard, 2009; Swim et al., 2001), and experiences of sexism have been consistently linked to psychological distress and alcohol use among heterosexual women (Fischer & Holz, 2010; Moradi & DeBlaere, 2010; Petzel & Casad, 2019; Sabik & Tylka, 2006; Szymanski et al., 2009). Furthermore, sexism partially accounts for gender differences in anxiety and depression between cisgender men and cisgender women (Klonoff et al., 2000) and contributes to psychological distress over and above general stressful life events among women (Landrine et al., 1995). Consistent findings also suggest that women engage in alcohol and drug use as a means of coping with excess stress associated with the accumulation of sexism (E. R. Carr & Szymanski, 2011; Petzel & Casad, 2019; Szymanski et al., 2011; Zucker & Landry, 2007).

Understanding health risks associated with sexism among sexual minority women (e.g., SMW; those who identify as lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, queer, or same-gender loving), including those who identify as gender diverse, such as genderqueer, transgender, nonbinary, or gender fluid, is needed given that this population faces an early and persistent disproportionate burden of mental and behavioral health issues, including psychological distress and alcohol- and drug-related consequences, compared to heterosexual women (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Hughes et al., 2014; Marshal et al., 2012, 2013; J. R. Pharr et al., 2019; Rice et al., 2019). For instance, multiple studies demonstrate that SMW are more likely to report anxiety and depression than heterosexual women (Coulter et al., 2015; Gonzales et al., 2016; J. R. Pharr et al., 2019). Compared to heterosexual women, SMW are 2 to 4 times as likely to report hazardous drinking (i.e., drinking that increases risk of harmful consequences; Drabble et al., 2013; Hughes et al., 2014); they are 11 times as likely to meet criteria for alcohol dependence (Drabble et al., 2005). Moreover, bisexual women are 2 to 6 times as likely to use illicit substances, such as opiates and methamphetamines, and misuse prescription drugs, than heterosexual women (Kerr et al., 2015; Scheer et al., 2019).

SMW experience unique stressors that confer risk for poor mental and behavioral health in this population (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003; Wilson et al., 2016) including heterosexism (Szymanski & Owens, 2009) and sexism (for example, discrimination, rape, and physical abuse; S. Pharr, 1997; Swim et al., 2007; Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014). Pervasive exposure to heterosexism and sexism might lead SMW to internalize negative beliefs about themselves, conceal their identities, and chronically expect rejection—psychological processes that might contribute to SMW’s consumption of alcohol or drugs to cope with the negative feelings associated with heterosexist bias, discrimination, traditional gender role stereotyping, and unwanted sexually objectifying comments and behaviors (Dyar et al., 2018; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; McCabe et al., 2010; Swim et al., 2001). Notably, these stressors are consistently associated with deleterious mental and behavioral health outcomes among SMW, including anxiety, depression, alcohol use, and drug use (Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; Lewis et al., 2016; Puckett et al., 2016a). However, there remains a lack of nuanced understanding of heterogeneity in sexism exposure and associated health risks among SMW subgroups—findings that can help to inform affirming prevention and intervention efforts.

There is growing recognition of SMW’s unique vulnerability to sexism as compared to heterosexual women (Lehavot et al., 2019). Indeed, for SMW, heterosexism can also serve as a “weapon of sexism” by enforcing rigid gender roles, women’s submission and subordination to men, and compulsory heterosexuality (S. Pharr, 1997). For example, SMW report being assaulted for not acting according to traditional gender roles, for refusing men’s sexual advances, and for being gender nonconforming (Fernald, 1995), findings that underscore the intersection of heterosexist bias and sexism facing SMW (Friedman & Leaper, 2010; Lehavot & Lambert, 2007; Rich, 1980). However, limited research has examined the impact of sexism in a sample of gender-diverse SMW, including whether the association between sexism and mental and behavioral health risks might vary as a function of gender identity and presentation (DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013). The current study aims to advance knowledge of how exposure to sexism relates to SMW’s, including those who are gender diverse, psychological distress (e.g., anxiety, depression) and alcohol- and drug-related consequences.

SMW’s Exposure to Sexism and Its Mental and Behavioral Health Correlates

While the majority of research among SMW has focused on experiences of heterosexism facing this population (Brooks, 1981; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; Meyer, 2003; Wilson et al., 2016), far less attention has been paid to SMW’s experiences of sexism (S. Pharr, 1997; Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014; Szymanski & Moffitt, 2012; Watson et al., 2018). Among the few studies that have examined the frequency of sexist experiences among SMW (e.g., C. L. Carr, 2011; DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013; Dyar et al., 2015; Lehavot et al., 2019; Watson et al., 2018), one study documented that, in the past 6 months, most heard sexist jokes about women, encountered disapproval for exhibiting gender-nonconforming behavior, and were called a sexist name and heard sexist comments about their body parts or clothing; nearly half were sexually threatened; and 17% experienced gender-based violence (Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014). Other findings reveal that almost twice as many SMW experienced rape in adulthood compared to heterosexual women, with the majority of perpetrators being men (Balsam et al., 2005).

Findings are mixed across the limited literature regarding mental and behavioral health risks associated with SMW’s experiences of sexism. For instance, some studies demonstrate that sexist experiences uniquely contribute to SMW’s mental and behavioral health and well-being over and above the impact of general stress and sexual orientation-based stressors, such as heterosexism (Brewster et al., 2014; Lehavot & Simpson, 2014; Szymanski, 2005; Szymanski et al., 2014; Szymanski & Owens, 2009; Watson et al., 2018). Conversely, one recent study demonstrated that, when accounting for race- and sexual-orientation-based discrimination, sexism did not emerge as a unique predictor of alcohol-related consequences among SMW of color (Cerezo & Ramirez, 2020). Given the prevalence of sexism facing SMW (Szymanski & Henrichs-Beck, 2014), additional research is needed to clarify the link between sexism and mental and behavioral health outcomes in this population.

Furthermore, virtually no empirical research, to our knowledge, has examined the association between SMW’s sexism and the extent to which SMW’s drug use caused any negative consequences. Understanding the link between sexism and alcohol- and drug-related consequences among SMW could help identify those most at risk for engaging in high-risk alcohol and drug use despite negative consequences (Mallett et al., 2006). Moreover, it is critical to consider within-group differences in psychological distress and alcohol- and drug-related consequences in this population in order to inform targeted prevention and intervention efforts (Hughes, 2011). As such, in addition to examining mental health (i.e., psychological distress) and behavioral health (i.e., alcohol- and drug-related consequences) correlates of sexism among SMW, the current study also considered subgroups of SMW for whom this link might be more pronounced, such as those who identify as gender minorities or are masculine-presenting.

The Moderating Role of Gender Identity and Presentation

SMW’s gender identity (e.g., cisgender, genderqueer, gender fluid) and presentation (e.g., appearance, gender roles, behaviors) often transcend traditional, heteronormative gender roles (Eagly, 2013; Feinberg, 1996; Halberstam, 1998; Levitt et al., 2012). Intersectionality theory represents a useful framework for studying the ways in which SMW’s social identity and inequality function interdependently (Bowleg, 2008) and how social identities interact to form novel experiences that are distinct from the individual constituent identities themselves or their sum (Cole, 2009; DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016; Parent et al., 2013; Puckett et al., 2016b). While few studies have examined whether mental and behavioral health risks associated with sexism might differ for SMW based on their sexual and gender identity, accumulating evidence suggests that SMW experience different gender-related stressors based on the extent to which they violate traditional gender norms (Lehavot et al., 2012). For example, SMW who identify their gender as nonbinary or who are masculine-presenting deviate from and resist conforming to society’s binary gender norms and thus may pose greater threat to male dominance and control over women (Connell, 1987; Horn, 2007; Lehavot & Lambert, 2007). One study demonstrated that women with relatively masculine personality traits (e.g., assertive, dominant, independent) experienced more sexual harassment than women with relatively feminine personality traits (e.g., modesty, deference, warmth; Berdahl, 2007). In contrast, feminine-presenting, cisgender SMW tend to report experiencing more objectification than masculine-presenting SMW, in part because SMW who conform to female gender stereotypes are often eroticized and viewed as sexual objects by cisgender men (Hequembourg & Brallier, 2009; Kury et al., 2004; Levitt et al., 2003; Levitt & Hiestand, 2004). These findings underscore the complexity of SMW’s experiences of sexism based on gender identity and presentation.

Feminist scholars have emphasized the importance of examining health consequences of sexism exposure in the context of other marginalized sociodemographic factors, such as gender minority identities and gender nonconformity among diverse groups of women, including SMW (DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013; S. Pharr, 1997; Szymanski & Owens, 2009). It is possible that sexism might confer distinct health risks among SMW as a function of gender identity (e.g., cisgender vs. gender minority) and presentation (feminine vs. masculine). That is, for SMW who identify as gender minorities or who are masculine-presenting, in addition to managing stress associated with deviating from traditional gender norms, many might also internalize more masculine sociocultural standards of attractiveness, behavior, and gender roles (Fleming & Agnew-Brune, 2015; Henrichs-Beck & Szymanski, 2017; Velez et al., 2016). As such, sexism (e.g., experiences of traditional gender role stereotyping and prejudice, and unwanted sexually objectifying comments and behavior) might be experienced as incongruent or dysphoric for gender minority or masculine-presenting SMW. Furthermore, sexism might reinforce gender minority or masculine-presenting SMW’s negative feelings associated with being unfeminine or not following cisgender men’s standards of female attractiveness (Brewster et al., 2014). However, few studies have examined whether sexism is associated with worse mental and behavioral health among SMW who identify as gender minorities or are masculine-presenting compared to SMW who identify as cisgender or are feminine-presenting. Documenting SMW’s possibly distinct experiences and health risks associated with sexism based on gender identity or presentation could elucidate vulnerable subgroups of SMW who might be in need of targeted prevention and intervention efforts (DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013; Hughes, 2011).

The Present Study

The current study aims to add to the emerging body of literature on the experiences of sexism among SMW. First, we sought to examine associations between sexism and three mental and behavioral health outcomes that disproportionately affect SMW compared to heterosexual women (Hughes et al., 2014; Marshal et al., 2013, Rice et al., 2019), including psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, and drug-related consequences. We hypothesized that greater exposure to sexism would be associated with greater psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, and drug-related consequences among SMW (Hypothesis 1). Second, we sought to examine the influence of SMW’s gender identity and presentation on the association between sexism and psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, and drug-related consequences. Based on previous literature suggesting that SMW who identify as gender minorities or are masculine-presenting might experience sexism as contradicting societal expectations of hegemonic masculinity (Lehavot et al., 2012; Velez, et al., 2016), we hypothesized that sexism would be more strongly associated with psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, and drug-related consequences among SMW who identify as gender minorities (Hypothesis 2) or are masculine-presenting (Hypothesis 3) relative to those who identify as cisgender or are feminine-presenting, respectively.

Method

Participants

Data were taken from the 60 SMW who enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of a 10-session transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral intervention adapted for SMW, described elsewhere (Pachankis et al., 2020). This pilot trial focused on young adult SMW, given that young adulthood is a developmental period characterized by identity-related stressors (e.g., “coming out,” homophobic victimization) as well as increased risk for mental health issues and experimentation with alcohol and drugs (Balsam et al., 2005; Kosciw et al., 2012; Marshal et al., 2012). The current study’s analyses included several baseline measures that participants completed prior to receiving the intervention.

From July 2018 through January 2019; participants were recruited from local events and venues, such as LGBTQ Pride events and bars, online listservs, college counseling centers, community organizations, and businesses serving sexual and gender minority populations. Participants were also sampled through targeted advertisements on social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, reddit). All potential participants completed a brief online eligibility questionnaire. Eligibility criteria included being between 18 and 35 years of age, identifying as a sexual minority woman (e.g., lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, queer), reporting symptoms of depression or anxiety within the past three months, reporting at least one episode of binge drinking (≥4 drinks in one sitting) within the past three months, reporting New York City residence within the past 12 months, and reporting English fluency. Drug use was not included in the eligibility questionnaire. A cutoff value of ≥2.5 on the depression or anxiety subscales of the 4-item Brief Symptom Inventory was used to identify the presence of depression or anxiety symptoms, following the recommended cutoff for sensitive and specific assessment of the presence of these disorders (Lang et al., 2009). Respondents were compensated $25 for participating in the baseline survey. To protect against participants’ fatigue and to ensure that sensitive measures were completed in person, participants completed half of the survey measures at home and the other half of the survey measures on site. Specifically, once participants confirmed their in-person appointment, they were instructed to first complete the at-home portion of the survey. On average, participants completed the in-person survey 4.26 days after completing the at-home survey (SD = 4.18; range = 1 to 16). All participants provided informed consent, and study procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committee at Yale University.

Participants ranged in ages from 19 to 32 (M = 25.58, SD = 3.26). A slight majority of participants identified as cisgender (56.7%), with the remainder identifying as gender minority (43.3%). Slightly more than half of participants identified their sexual orientation as queer (55.0%), with equal numbers identifying as lesbian (15.0%) and bisexual (15.0%). Less than half of participants identified as racial or ethnic minorities (41.7%), and around half of the sample had obtained a four-year college degree (56.7%), were employed full time (40+ hours per week; 55.0%), earned less than $29,999 annually (50.0%), and were currently partnered (48.3%).

Measures

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the entire sample. Participants indicated their age; gender identity (i.e., cisgender woman, trans man, trans woman, genderqueer, gender nonconforming, gender fluid, gender nonbinary, hijra, Two-Spirit, questioning, and other); sexual orientation (i.e., lesbian, queer, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, and uncertain); race or ethnicity (i.e., American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Multiracial, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, White, and other); education level (i.e., some high school to graduate degree); employment status (i.e., full time [40 hr per week] to unemployed); personal income (i.e., less than $10,000 to $75,000 or more); and relationship status (i.e., single, casually dating, and partnered).1 Participants could endorse more than one gender identity. Participants were limited to endorsing one sexual orientation. Those who identified as cisgender men or heterosexual were not eligible for this study.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics of Sexual Minority Women (N = 60)

| Total sample |

||

|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristics | n | % |

| Age, years (range: 19 – 32) | ||

| Mean | 25.58 | |

| SD | 3.26 | |

| Gender identity | ||

| Cisgender woman | 34 | 56.7 |

| Gender minority | 26 | 43.3 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Queer | 33 | 55.0 |

| Bisexual | 9 | 15.0 |

| Lesbian | 9 | 15.0 |

| Pansexual | 5 | 8.3 |

| Asexual | 2 | 3.3 |

| Uncertain | 2 | 3.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 35 | 58.3 |

| Black/African American | 7 | 11.7 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 5 | 8.3 |

| Other | 5 | 8.3 |

| Asian | 4 | 6.7 |

| Multiracial | 4 | 6.7 |

| Education level | ||

| 4-year college degree | 34 | 56.7 |

| Some college/currently in college | 13 | 21.7 |

| Some graduate school or higher | 9 | 15.0 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time (40+ hours per week) | 33 | 55.0 |

| Part-time employment (<40 hours per week) | 16 | 26.6 |

| Student | 7 | 11.7 |

| Unemployed | 4 | 6.7 |

| Personal income, annually | ||

| Less than $29,999 | 30 | 50.0 |

| More than $50,000 | 15 | 25.0 |

| $30,000–$49,000 | 11 | 18.3 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Partnered | 29 | 48.3 |

| Single or casually dating | 27 | 45.0 |

Note. Gender minority included sexual minority women who identified as genderqueer, gender nonconforming, gender fluid, gender nonbinary, Two-Spirit, questioning, or other (e.g., trans femme).

Masculine Gender Presentation

This study used a continuous measure of gender presentation rather than requiring participants to identify with a single label, such as “butch” or “femme” (Wylie et al., 2010). Participants responded to two items in which they indicated social perceptions of gender nonconformity in their appearance and mannerisms (Wylie et al., 2010). The item assessing appearance was “A person’s appearance, style, or dress may affect the way people think of them. On average, how do you think people would describe your appearance, style, or dress?” The item assessing mannerisms was “A person’s mannerisms (such as the way they walk or talk) may affect the way people think of them. On average, how do you think people would describe your mannerisms?” Participants rated their appearance and mannerisms based on their perceptions of how other people would describe them on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (very feminine) to 7 (very masculine). These two items were averaged, and higher scores represented greater masculine gender presentation whereas lower scores represented greater feminine gender presentation. This measure of gender presentation has shown sufficient reliability with SMW, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .89 to .92 (S. M. Steele et al., 2019). Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was .79.

Psychological Distress

The anxiety and depression subscales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983; Meijer et al., 2011) were used to assess participant’s level of self-reported psychological distress over the past three months. Examples of the 12 items include “Nervousness or shakiness inside” and “Feeling lonely.” Response options ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Mean scores were calculated separately for the anxiety and depression subscales. These scores were then averaged, and higher scale scores represented greater self-reported psychological distress. The BSI has shown good internal consistency with heterosexual women and SMW (α = .86; López & Yeater, 2018). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .84 for the anxiety subscale and .85 for the depression subscale. Cronbach’s alpha for psychological distress for the current sample was .86.

Alcohol-Related Consequences

Participants responded to a 15-item scale that assessed the extent to which their alcohol use caused any adverse consequences in the past three months. Self-reported alcohol-related consequences were assessed using the Short Inventory of Problems—Alcohol (SIP-A; Alterman et al., 2009; Blanchard et al., 2003). A sample item is “I have failed to do what is expected of me because of my drinking.” Response options to each were 0 (no) and 1 (yes). Higher total scale scores represent more alcohol-related consequences. The SIP-A has shown good reliability with SMW (α = .93; Lewis et al., 2017). Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was .78.

Drug-Related Consequences

Participants responded to a 15-item scale that assessed the extent to which their drug use caused any adverse consequences in the past three months. Self-reported drug-related consequences was assessed using the Short Inventory of Problems—Drugs (SIP-D; Blanchard et al., 2003). A sample item is “When using drugs, I have done impulsive things that I regretted later.” Response options to each were 0 (no) and 1 (yes). Higher total scale scores represent more drug-related consequences. The SIP-D has shown good reliability with LGBTQ samples, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .92 to .95 (Gillespie & Blackwell, 2009). Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was .78.

Sexism

Participants reported past-year experiences of sexism. Exposure to daily occurrences of sexism was assessed with the 20-item Schedule of Sexist Events (SSE; Klonoff & Landrine, 1995). Sample items include “How many times were you denied a raise, a promotion, tenure, a good assignment, a job, or other such thing at work that you deserved because you are a woman?” and “How many times have people made inappropriate or unwanted sexual advances to you because you are a woman?” Response options ranged from 0 (never) to 6 (almost all of the time), with higher average scores indicating greater exposure to sexism. The SSE has shown good internal consistency with SMW (Cronbach’s alpha = .94; DeBlaere & Bertsch, 2013; Lehavot et al., 2019). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .94 for the total sample of SMW, .96 for gender minority SMW, and .91 for cisgender SMW.

Analytic Plan

Data analyses using the full sample of 60 SMW were conducted using SPSS Version 26. There was no missing data across study variables. Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Then, bivariate correlations (for continuous variables) and independent samples t-tests (for dichotomous variables) were examined for sexism, masculine gender presentation, gender identity, psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, drug-related consequences, and covariates that have been linked to mental and behavioral health in prior research among SMW, namely age and race/ethnicity (Dyar et al., 2018; Kertzner et al., 2009; Lehavot et al., 2019; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; Lewis et al., 2014; Molina et al., 2015). Dependent variables were assessed for normality using skewness and kurtosis thresholds of ±2 (Field, 2013; George & Mallery, 2010). All outcome variables demonstrated normal distribution.

Next, six moderated linear regression models were estimated to test each of the two potential moderators (i.e., gender identity and masculine gender presentation) of the association between sexism and mental and behavioral health (i.e., psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, and drug-related consequences) utilizing the SPSS PROCESS Macro Version 3.40 (Hayes, 2012). Specifically, six linear regression models using 1,000 bootstrap resamples examined interactions between sexism and gender identity and masculine gender presentation on psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, and drug-related consequences. Given the potential for multicollinearity between gender identity and masculine gender presentation, they were treated as independent moderator variables in separate models to conserve statistical power and to avoid committing Type II error (Hayes, 2013).

The PROCESS procedures use ordinary least squares regression and bootstrapping methodology, which confers more statistical power than standard approaches to statistical inference and does not rely on distributional assumptions (Hayes, 2013). Prior to creating interaction terms, continuous independent variables were mean-centered to reduce the risk of multicollinearity and to increase the interpretability of the intercept. Both the total and change in R-squared statistic with the F test are reported for each moderated linear regression model to indicate goodness of fit, respectively. Following the methods suggested by Aiken and West (1991), regression slopes were plotted separately for cisgender SMW and gender minority SMW and at one standard deviation above and below mean levels of masculine gender presentation.

In addition, using the Johnson-Neyman technique, we calculated the region(s) of significance within which the conditional effects of sexism on our three mental and behavioral health outcomes are significant along the continuous distribution of masculine gender presentation (Hayes, 2013). Sensitivity analyses tested the moderation analyses again without controlling for age and race/ethnicity given that these demographic characteristics were not associated with our three primary outcome variables (Figueroa & Zoccola, 2015; Lewis et al., 2006). A significance level of α = .05 was applied when testing all study hypotheses. Follow-up analyses were conducted to examine whether the slopes of the regression lines significantly differed from zero. A power analysis using the statistical program G*Power determined that 60 participants provided 80% power to detect a small-to-medium effect (Faul et al., 2007).

Results

Associations Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Study Variables

Table 2 presents the bivariate associations among study variables as well as basic descriptive statistics for each continuous variable. Bivariate analyses revealed a significant association between alcohol-related consequences and drug-related consequences (r = .35, p = .01). Sexism was positively associated with psychological distress (r = .26, p = .04), alcohol-related consequences (r = .29, p = .03), and drug-related consequences (r = .30, p = .02), respectively.

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations Among Continuous Study Variables in the Full Sample of Sexual Minority Women

| Continuous study variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | |||||

| 2. Sexism | .01 | — | ||||

| 3. Masculine gender presentation | −.08 | .06 | — | |||

| 4. Psychological distress | −.23 | .26* | −.01 | — | ||

| 5. Alcohol-related consequences | .12 | .29* | .07 | .16 | — | |

| 6. Drug-related consequences | .03 | .30* | .24 | .12 | .35** | — |

| Mean (SD) | 25.58 (3.26) | 50.88 (17.96) | 3.28 (1.36) | 1.77 (.68) | 3.78 (3.01) | 1.33 (2.07) |

| Range | 19–32 | 25–100 | 1–6 | .33–4 | 0–10 | 0–8 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

SMW who identified as gender minorities reported higher mean levels of masculine gender presentation (M = 3.94, SD = 1.29) than cisgender SMW (M = 2.73, SD = 1.18); t(58) = −3.81, p < .001. There were no differences in sexism, psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, drug-related consequences, age, and race/ethnicity between gender minority SMW and cisgender SMW. There were also no differences on all study variables between white SMW and racial/ethnic minority SMW.

Gender Identity and Masculine Gender Presentation as Moderators of the Association Between Sexism and Psychological Distress

As indicated in Table 3, the interaction between sexism and gender identity accounted for 21% of the variance in psychological distress (F[5,54] = 2.80, p = .03; Model 1). In the model examining the interaction between sexism and gender identity on psychological distress, a significant main effect was not found for sexism (b = −.01, SE = .01, p = .91) or for gender identity (b = −.13, SE = .17, p = .45). However, the interaction between sexism and gender identity was significantly associated with more psychological distress (b = .02, SE = .01, p = .04). Simple slopes analysis revealed that sexism was significantly associated with more psychological distress only for gender minority SMW (b = .02, SE = .01, p = .01) but not for cisgender SMW (b = −.01, SE = .01, p = .91; see Figure 1).

Table 3.

Moderation Results of the Association Between Sexism and Psychological Distress

| Psychological distress |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | t | 95% CI | R 2 | F | ΔR2 | ΔF |

| Model 1 | .21 | 2.80* | .06 | 4.18* | ||||

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Age | −0.05* | 0.03 | −2.09 | [−0.11, −0.01] | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | −0.15 | 0.17 | −0.86 | [−0.48, 0.19] | ||||

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexism | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.12 | [−0.02, 0.01] | ||||

| Gender identity | −0.13 | 0.17 | −0.76 | [−0.46, 0.21] | ||||

| Interaction effect | ||||||||

| Sexism × Gender identity | 0.02* | 0.01 | 2.04 | [0.01, 0.04] | ||||

| Model 2 | .21 | 2.78* | .07 | 4.62* | ||||

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Age | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.61 | [−0.09, 0.01] | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | −0.22 | 0.17 | −1.30 | [−0.56, 0.12] | ||||

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexism | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.47 | [−0.01, 0.02] | ||||

| Masculine gender presentation | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.22 | [−0.14, 0.11] | ||||

| Interaction effect | ||||||||

| Sexism × Masculine gender presentation | 0.01* | 0.01 | 2.15 | [0.01, 0.02] | ||||

Note. Unstandardized β coefficients are reported. Model 1 includes gender identity as a moderator variable. Model 2 includes masculine gender presentation as a moderator variable. Race/ethnicity: 0 = White; 1 = racial/ethnic minority. Gender identity: 0 = cisgender; 1 = gender minority.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Sexism Exposure by Gender Identity for Psychological Distress

The interaction between sexism and masculine gender presentation accounted for 21% of the variance in psychological distress (F[5,54] = 2.78, p = .03; Model 2). In the model examining the interaction between sexism and masculine gender presentation on psychological distress, a significant main effect was not found for sexism (b = .01, SE = .01, p = .15) or for masculine gender presentation (b = −.01, SE = .06, p = .83). However, the interaction between sexism and masculine gender presentation was significantly associated with more psychological distress (b = .01, SE = .01, p = .04). Simple slopes analysis revealed that sexism was significantly associated with more psychological distress only for SMW who report high masculine gender presentation (1 SD above the mean; b = .02, SE = .01, p = .01), but not for SMW who report low masculine gender presentation (1 SD below the mean; b = −.01, SE = .01, p = .72; see Figure 2). Results of the Johnson-Newman technique demonstrated that the region of significance of the association between sexism and psychological distress ranged from values higher than .29 (i.e., .21 SD above the mean) on masculine gender presentation to the maximum score of 2.73 (i.e., 1.99 SD above the mean). In other words, sexism was predictive of psychological distress at values of masculine gender presentation greater than .29 (65th percentile).

Figure 2.

Sexism Exposure by Masculine Gender Presentation for Psychological Distress

Gender Identity and Masculine Gender Presentation as Moderators of the Association Between Sexism and Alcohol-Related Consequences

As indicated in Table 4, the interaction between sexism and gender identity accounted for 10% of the variance in alcohol-related consequences (F[5,54] = 1.21, p = .32; Model 3). Specifically, in the model examining the interaction between sexism and gender identity on alcohol-related consequences, the main effects for sexism (b = .05, SE = .03, p = .14) and gender identity (b = .08, SE = .78, p = .91) were not significant. The interaction between sexism and gender identity was also not significantly associated with alcohol-related consequences (b = −.01, SE = .04, p = .92).

Table 4.

Moderation Results of the Association Between Sexism and Alcohol-Related Consequences

| Alcohol-related consequences |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | t | 95% CI | R 2 | F | ΔR2 | ΔF |

| Model 3 | .10 | 1.21 | .01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Age | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.86 | [−0.14, 0.35] | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | −0.34 | 0.79 | −0.43 | [−1.94, 1.25] | ||||

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexism | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.49 | [−0.02, 0.12] | ||||

| Gender identity | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.11 | [−1.48, 1.65] | ||||

| Interaction effect | ||||||||

| Sexism × Gender identity | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.10 | [−0.09, 0.08] | ||||

| Model 4 | .12 | 1.41 | 0.01 | 0.71 | ||||

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Age | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1.02 | [−0.12, 0.37] | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | −0.43 | 0.79 | −0.54 | [−2.02, 1.16] | ||||

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexism | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.86 | [−0.01, 0.09] | ||||

| Masculine gender presentation | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.50 | [−0.43, 0.71] | ||||

| Interaction effect | ||||||||

| Sexism × Masculine gender presentation | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.84 | [−0.02, 0.05] | ||||

Note. Unstandardized β coefficients are reported. Model 3 includes gender identity as a moderator variable. Model 4 includes masculine gender presentation as a moderator variable. Race/ethnicity: 0 = White; 1 = racial/ethnic minority. Gender identity: 0 = cisgender; 1 = gender minority.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The interaction between sexism and masculine gender presentation accounted for 12% of the variance in alcohol-related consequences (F[5,54] = 1.41, p = .23; Model 4). In the model examining the interaction between sexism and masculine gender presentation on alcohol-related consequences, the main effects for sexism (b = .04, SE = .02, p = .07) and masculine gender presentation (b = .14, SE = .28, p = .62) were not significant. The interaction between sexism and masculine gender presentation was also not significantly associated with alcohol-related consequences (b = .01, SE = .02, p = .40).

Gender Identity and Masculine Gender Presentation as Moderators of the Association between Sexism and Drug-Related Consequences

As indicated in Table 5, the interaction between sexism and gender identity accounted for 11% of the variance in drug-related consequences (F[5,54] = 1.29, p = .28; Model 5). In the model examining the interaction between sexism and gender identity on drug-related consequences, the main effects for sexism (b = .04, SE = .02, p = .07) and gender identity (b = −.47, SE = .54, p = .38) were not significant. Furthermore, the interaction between sexism and gender identity was not significantly associated with drug-related consequences (b = −.01, SE = .03, p = .67).

Table 5.

Moderation Results of the Association Between Sexism and Drug-Related Consequences

| Drug-related consequences |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | t | 95% CI | R 2 | F | ΔR2 | ΔF |

| Model 5 | .11 | 1.29 | .01 | 0.19 | ||||

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.19 | [−0.15, 0.18] | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.15 | 0.54 | 0.27 | [−0.95, 1.24] | ||||

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexism | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.82 | [−0.01, 0.09] | ||||

| Gender identity | −0.47 | 0.54 | −0.88 | [−1.55, 0.61] | ||||

| Interaction effect | ||||||||

| Sexism × Gender identity | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.43 | [−0.07, 0.05] | ||||

| Model 6 | .21 | 2.76* | .06 | 4.19* | ||||

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Age | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.76 | [−0.09, 0.22] | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | −0.01 | 0.52 | −0.01 | [−1.04, 1.03] | ||||

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sexism | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.52 | [−0.01, 0.05] | ||||

| Masculine gender presentation | 0.36 | 0.19 | 1.92 | [−0.02, 0.73] | ||||

| Interaction effect | ||||||||

| Sexism × Masculine gender presentation | 0.02* | 0.01 | 2.05 | [0.01, 0.04] | ||||

Note. Unstandardized β coefficients are reported. Model 5 includes gender identity as a moderator variable. Model 6 includes masculine gender presentation as a moderator variable. Race/ethnicity: 0 = White; 1 = racial/ethnic minority. Gender identity: 0 = cisgender; 1 = gender minority.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

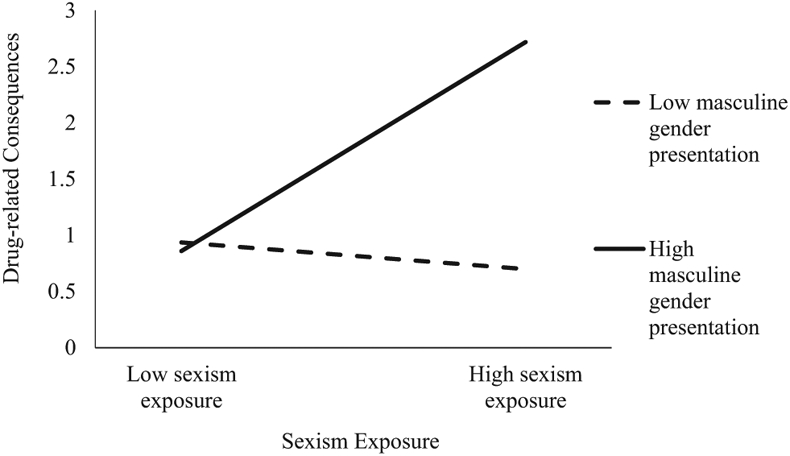

The interaction between sexism and masculine gender presentation accounted for 21% of the variance in drug-related consequences (F[5,54] = 2.76, p = .02; Model 6). In the model examining the interaction between sexism and masculine gender presentation on drug-related consequences, the main effects for sexism (b = .02, SE = .01, p = .14) and masculine gender presentation (b = .36, SE = .19, p = .06) were not significant. However, the interaction between sexism and masculine gender presentation was significantly associated with drug-related consequences (b = .02, SE = .01, p = .04). Simple slopes analysis revealed that sexism was significantly associated with drug-related consequences only for SMW who report high masculine gender presentation (1 SD above the mean; b = .05, SE = .02, p = .01), not for SMW who report low masculine gender presentation (1 SD below the mean; b = −.01, SE = .02, p = .78; see Figure 3). Results of the Johnson-Newman technique demonstrated that the region of significance of the association between sexism and drug-related consequences ranged from values higher than .28 (i.e., .21 SD above the mean) on masculine gender presentation to the maximum score of 2.73 (i.e., 2.01 SD above the mean). In other words, sexism was predictive of drug-related consequences at values of masculine gender presentation greater than .28 (65th percentile).

Figure 3.

Sexism Exposure by Masculine Gender Presentation for Drug-Related Consequences

Finally, sensitivity analyses revealed that the direction, magnitude, and significance of effects for each model remain largely the same regardless of whether models controlled for age and race/ethnicity, as reported above.

Discussion

In this study, we found that sexism was bivariately associated with greater psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, and drug-related consequences in a sample of gender-diverse SMW, consistent with our Hypothesis 1 and with existing literature among women more broadly (Carliner et al., 2017; E. R. Carr & Szymanski, 2011; Klonoff et al., 2000; Ro & Choi, 2010; Swim et al., 2001; Zucker & Landry, 2007). This is among the first studies to test the association between SMW’s sexism and the extent to which SMW’s alcohol and drug use caused any negative consequences. Building on prior research that has primarily focused on the corrosive impact of sexism on bisexual-identified women (e.g., Watson et al., 2018) or lesbian-identified women specifically (e.g., Szymanski, 2005), the current study is also one of the first studies to our knowledge to examine whether sexism is associated with worse mental and behavioral health among SMW who identify as gender minorities or are masculine-presenting compared to SMW who identify as cisgender or are feminine-presenting. We did not find significant associations between either gender identity or masculine gender presentation and psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, or drug-related consequences. However, moderation analyses revealed significant interactions between sexism and mental and behavioral health across SMW’s gender identity and presentation.

In relation to psychological distress, consistent with our hypotheses (Hypothesis 2) we found that sexism was significantly associated with more psychological distress for gender minority SMW but not for cisgender SMW. Sexism was also significantly associated with more psychological distress for SMW who report high masculine gender presentation but not for those who report low masculine gender presentation (Hypothesis 3). These findings are congruent with accumulating evidence suggesting that the psychological toll of sexism among SMW may be related to the extent to which this population violates traditional gender norms, thereby threatening the status quo (Lehavot et al., 2012). This finding may be indicative of gender minority or masculine-presenting SMW posing a greater threat to male dominance or patriarchal cultural norms (Connell, 1987; Horn, 2007; Lehavot & Lambert, 2007; Levitt et al., 2003; Levitt & Hiestand, 2004; S. Pharr, 1997). Based on this perceived threat, gender minority or masculine-presenting SMW might experience sexism as particularly harmful or devaluing, which may in turn lead to stereotype-threat effects, including anxiety and depression (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980; C. M. Steele & Aronson, 1995). Notably, while SMW did not vary in their level of exposure to sexism based on their gender identity or presentation, for SMW who identified as gender minority or were masculine-presenting, sexism was associated with more psychological distress compared to SMW who identified as cisgender or were feminine-presenting. As such, future studies should investigate whether sexism (e.g., experiences of traditional gender role stereotyping and prejudice, and unwanted sexually objectifying comments and behavior) may be experienced as particularly incongruent or dysphoric for gender minority and masculine-presenting SMW.

While we did find bivariate associations between exposure to sexism and alcohol-related consequences and drug-related consequences, we did not find significant bivariate associations between either gender identity or masculine gender presentation and alcohol- or drug-related consequences. Prior studies have demonstrated inconsistent findings regarding the association between gender nonconformity and mental and behavioral health among sexual minorities. For instance, some studies have shown that psychological distress does not vary as a function of SMW’s gender nonconformity (Baams et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016), while other findings have demonstrated a positive association between gender nonconformity and poor mental and behavioral health among SMW (Plöderl & Fartacek, 2009; Puckett et al., 2016a; Roberts et al., 2013). Still, other research finds that gender nonconformity in and of itself may not relate to psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, or drug-related consequences (e.g., Li et al., 2016), consistent with the current study’s findings. Rather, for gender minority or masculine-presenting SMW, exposure to and internalization of gender-based stressors, including inappropriate sexual advances, might help to explain this population’s elevated risk of poor mental and behavioral health (Szymanski & Moffitt, 2012).

Extending this research, we did not find significant associations between exposure to sexism and alcohol- or drug-related consequences across gender identity (Hypothesis 2). Furthermore, the interaction between exposure to sexism and masculine presentation was not associated with alcohol-related consequences (Hypothesis 3). We did, however, identify an interaction between sexism and masculine presentation in relation to drug-related consequences, such that exposure to sexism was significantly associated with drug-related consequences only for SMW who report high masculine gender presentation, but not for SMW who report low masculine gender presentation (Hypothesis 3). That is, our findings suggest that for those whose gender presentation is inconsistent with patriarchal norms, exposure to sexism may lead to drug-related consequences, potentially consistent with a stress and coping model (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Our findings underscore the need to examine stress-sensitive mental and behavioral outcomes of sexism exposure among SMW diverse in gender identities and expressions.

Existing research suggests that women engage in alcohol and drug use as a means of coping with excess stress associated with the accumulation of sexist events (E. R. Carr & Szymanski, 2011; Szymanski et al., 2011; Zucker & Landry, 2007). The current study’s inconsistent results between alcohol and drug use outcomes reflects the extent to which sexism exposure might be uniquely associated with masculine-presenting SMW’s motives and expectancies (i.e., anticipated consequences) corresponding with drug use (Green & Feinstein, 2012; Patrick et al., 2010). For instance, masculine-presenting SMW experiencing sexism might use drugs to cope with or to decrease negative emotions associated with sexism (Cooper et al., 1992). Given that sexism might be experienced as incongruent or dysphoric for masculine-presenting SMW, this group might use drugs to cope with negative feelings associated with being unfeminine or not following cisgender men’s standards of female attractiveness (Brewster et al., 2014). Consistent evidence demonstrates that those endorsing coping-motivated drug use are at increased risk for drug-related consequences (Buckner et al., 2006). In addition, drug use is often considered a masculine behavior (Rosario et al., 2008; Wallace et al., 2003). Thus, masculine-presenting SMW might engage in problematic drug use given that this behavior might be consistent with their masculine presentation (Rosario et al., 2008). Other factors that were not captured in the current study, such as social context, pressure to drink, connection to other SMW, and perception of drinking norms in the community, represent important motives underlying SMW’s alcohol use (Condit et al., 2011; Ehlke et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2016). As such, future studies should examine these factors in relation to sexism and SMW’s mental and behavioral health.

Limitations

While this study offers a unique contribution to the literature on the experiences and mental and behavioral health correlates of SMW’s sexism, several limitations should be considered. First, the sample size is small; the participants are relatively young, and are mostly White and college-educated, which may have influenced the findings and limits generalizability to more diverse SMW. Given the sample size, we did not investigate whether the identified relationships differed across gender minority subgroups or differed by race, ethnicity, or other sociodemographic variables such as income or education level. Attention to the ways in which sexism may differentially impact SMW based on their multiple marginalized identities could help inform future prevention and intervention efforts for this population. As such, research using larger samples of diverse SMW across the U.S. is critically needed in order to meaningfully compare the association between sexism and mental and behavioral health across age, gender identity, racial/ethnic identity, and income or education level. In addition, given the inclusion criteria for the pilot intervention study (Pachankis et al., 2020), all participants lived in New York City, reported recent symptoms of depression or anxiety, and reported recent binge drinking, which could limit the generalizability and interpretability of the present study’s findings.

This study did not examine sexism in the context of other forms of discrimination (e.g., heterosexism, racism). Future research should consider examining the incremental role of sexism in explaining variance in SMW’s mental and behavioral health issues, above and beyond other forms of discrimination. Research is also needed to discern the extent to which multiple forms of oppression (i.e., sexism, racism, heterosexism, and cissexism) may additively or multiplicatively influence mental and behavioral health outcomes in a sample of gender-diverse SMW (Watson et al., 2016). Future research should also consider psychological (e.g., emotion dysregulation), gender-related (e.g., internalized sexism), or sexual-orientation-specific (e.g., internalized homophobia) mechanisms that might help to explain the association between sexism and mental and behavioral health among SMW. Additionally, our measure of masculine presentation (i.e., focusing on appearance and mannerisms) may have limited our ability to assess differences in experiences associated with stereotypically masculine versus feminine personality characteristics (e.g., assertiveness, dominance, and independence vs. modesty, deference, and warmth, respectively), which have been found to be associated with sexual harassment (Berdahl, 2007). The study’s cross-sectional design does not allow us to establish causality. In addition, while participants completed distinct measures at home and in person, it is possible that practice effects might have occurred. Finally, casual inference is also limited by our use of self-reported sexism and mental and behavioral health risks, given known confounds between mental health status and reports of stress experiences as well as limitations of same-source reporting bias (Dohrenwend et al., 1984; Meyer, 2003).

Conclusion

Compared to heterosexual women, SMW are at increased risk for mental and behavioral health problems as a result of chronic exposure to stigma-related stressors associated with their sexual orientation (Hughes et al., 2014; Marshal et al., 2011, 2012, 2013; Scheer et al., 2019). The current study extends prior research on minority stress and SMW’s mental and behavioral health by highlighting the role of sexism as a potential contributor to psychological distress, alcohol-related consequences, and drug-related consequences in this population. Our findings also underscore the importance of considering gender identity and presentation as potential moderators of the association between exposure to sexism and SMW’s mental and behavioral health risks.

This study identifies the importance of considering the role of sexism, gender identity, and gender presentation in relation to SMW’s psychological distress and drug-related consequences. Findings suggest that mental health providers should be cognizant of the association between sexism and mental and behavioral health among gender minority and masculine-presenting SMW. Furthermore, when considering the association between sexism and mental and behavioral health among SMW, clinicians might consider subgroups of SMW for whom this link might be more pronounced, such as those who identify as gender minorities or are masculine-presenting. Future research should examine how risk for or consequences of sexism among SMW may vary across other intersecting identities, such as race/ethnicity, immigration status, or socioeconomic status. Documenting similarities and differences in the manifestation and impact of sexism across diverse groups of SMW is critical to advancing mental and behavioral health intervention and prevention efforts for this understudied and at-risk population.

Public Significance Statement.

This study advances our understanding of sexual minority women subgroups for whom the link between sexism and mental and behavioral health might be more pronounced, such as those who identify as gender minorities or are masculine-presenting. These findings underscore the importance of considering whether sexism (e.g., experiences of traditional gender role stereotyping and prejudice, and unwanted sexually objectifying comments and behavior) may be experienced as incongruent or dysphoric for gender minority or masculine-presenting SMW.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the study team: Oluwaseyi Adeyinka, Ricardo Albarran, Kriti Behari, Alex Belser, Cal Brisbin, Charles Burton, Kirsty Clark, Nitzan Cohen, Benjamin Fetzner, Emily Finch, Skyler Jackson, Rebecca Kaplan, Colin Kimberlin, Erin McConocha, Meghan Michalski, Faithlynn Morris, Zachary Rawlings, Maxwell Richardson, Craig Rodriguez-Seijas, Ingrid Solano, Timothy Sullivan, Tenille Taggart, Arjan van der Star, and Roxanne Winston. This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH109413-02S1: John E. Pachankis), the GLMA Lesbian Health Fund, the Fund for Lesbian and Gay Studies at Yale, and the David R. Kessler, MD ’55 Fund for LGBTQ Mental Health Research at Yale. Manuscript preparation was supported in part by the Yale Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS training program, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health under Award T32MH020031-20, in support of Jillian R. Scheer. Abigail W. Batchelder is supported by a Mentored Scientist Development Award (K23DA043418) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Katie Wang is supported by a Mentored Scientist Development Award (K01DA045738) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The research presented herein is the authors’ own and does not represent the views of the funders, including the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Due to small cell sizes and to provide adequate power for moderation analyses, gender identity was recoded into cisgender women and gender minorities, including gender queer, gender nonconforming, gender fluid, gender nonbinary, Two-Spirit, questioning, and other (e.g., trans femme). Similarly, racial and ethnic minority groups were collapsed into White and people of color, including American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Multiracial, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, and other.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Ivey MA, Habing B, & Lynch KG (2009). Reliability and validity of the alcohol short index of problems and a newly constructed drug short index of problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(2), 304–307. 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Beek T, Hille H, Zevenbergen FC, & Bos HMW (2013). Gender nonconformity, perceived stigmatization, and psychological well-being in Dutch sexual minority youth and young adults: A mediation analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(5), 765–773. 10.1007/s10508-012-0055-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, & Beauchaine TP (2005). Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 477–487. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdahl JL (2007). Harassment based on sex: Protecting social status in the context of gender hierarchy. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 641–658. 10.5465/amr.2007.24351879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard KA, Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, Labouvie E, & Bux DA (2003). Motivational subtypes and continuous measures of readiness for change: Concurrent and predictive validity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(1), 56–65. 10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2008). When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles, 59, 312–325. 10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, Velez BL, Esposito J, Wong S, Geiger E, & Keum BT (2014). Moving beyond the binary with disordered eating research: A test and extension of objectification theory with bisexual women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 50–62. 10.1037/a0034748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman BG, & Rickard KM (2009). College students’ descriptions of everyday gender prejudice. Sex Roles, 61, 461–75. 10.1007/s11199-009-9643-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VR (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Eggleston AM, & Schmidt NB (2006). Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: The mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behavior Therapy, 37(4), 381–391. 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carliner H, Sarvet AL, Gordon AR, & Hasin DS (2017). Gender discrimination, educational attainment, and illicit drug use among U.S. women. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(3), 279–289. 10.1007/s00127-016-1329-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CL (2011). Women’s bisexuality as a category in social research. Revisited. Journal of Bisexuality, 11(4), 550–559. 10.1080/15299716.2011.620868 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr ER, & Szymanski DM (2011). Sexual objectification and substance abuse in young adult women. The Counseling Psychologist, 39(1), 39–66. 10.1177/0011000010378449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo A, & Ramirez A (2020). Perceived discrimination, alcohol use disorder and alcohol-related problems in sexual minority women of color. Journal of Social Service Research, 47(1), 33–46. 10.1080/01488376.2019.1710657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64(3), 170–180. 10.1037/a0014564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit M, Kitaji K, Drabble L, & Trocki K (2011). Sexual minority women and alcohol: Intersections between drinking, relational contexts, stress, and coping. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 23(3), 351–375. 10.1080/10538720.2011.588930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, & Windle M (1992). Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment, 4(2), 123–132. 10.1037/1040-3590.4.2.123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RW, Kinsky SM, Herrick AL, Stall RD, & Bauermeister JA (2015). Evidence of syndemics and sexuality-related discrimination among young sexual-minority women. LGBT Health, 2(3), 250–257. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBlaere C, & Bertsch KN (2013). Perceived sexist events and psychological distress of sexual minority women of color: The moderating role of womanism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(2), 167–178. 10.1177/0361684312470436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Melisaratos N (1983). The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. 10.1017/S0033291700048017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP, Dodson M, & Shrout PE (1984). Symptoms, hassles, social supports, and life events: Problem of confounded measures. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93(2), 222–230. 10.1037/0021-843X.93.2.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Midanik LT, & Trocki K (2005). Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual respondents: Results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66(1), 111–120. 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Trocki KF, Hughes TL, Korcha RA, & Lown AE (2013). Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(3), 639–648. 10.1037/a0031486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Feinstein BA, Eaton NR, & London B (2018). The mediating roles of rejection sensitivity and proximal stress in the association between discrimination and internalizing symptoms among sexual minority women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 205–218. 10.1007/s10508-016-0869-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Feinstein BA, & London B (2015). Mediators of differences between lesbians and bisexual women in sexual identity and minority stress. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 43–51. 10.1037/sgd0000090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH (2013). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Erlbaum. 10.4324/9780203781906 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlke SJ, Stamates AL, Kelley ML, & Braitman AL (2019). Bisexual women’s reports of descriptive drinking norms for heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(2), 256–263. 10.1037/sgd0000312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, & Hyde JS (2016). Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: II. Methods and techniques. Methods and Techniques. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 319–336. 10.1177/0361684316647953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, & Buchner A (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg L (1996). Transgender warriors: Making history from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald JL (1995). Interpersonal heterosexism. In Lott B & Maluso D (Eds.), The social psychology of interpersonal discrimination (pp. 80–117). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Field A (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa WS, & Zoccola PM (2015). Individual differences of risk and resiliency in sexual minority health: The roles of stigma consciousness and psychological hardiness. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 329–338. 10.1037/sgd0000114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AR, & Holz KB (2010). Testing a model of women’s personal sense of justice, control, well-being, and distress in the context of sexist discrimination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(3), 297–310. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01576.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming PJ, & Agnew-Brune C (2015). Current trends in the study of gender norms and health behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 72–77. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Lazarus RS (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239. 10.2307/2136617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman C, & Leaper C (2010). Sexual-minority college women’s experiences with discrimination: Relations with identity and collective action. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(2), 152–164. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01558.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George D, & Mallery P (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step. A simple study guide and reference. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie W, & Blackwell RL (2009). Substance use patterns and consequences among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 21(1), 90–108. 10.1080/10538720802490758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, & Fiske ST (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491–512. 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, & Fiske ST (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118. 10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Fiske ST, Mladinic A, Saiz JL, Abrams D, Masser B, Adetoun B, Osagie JE, Akande A, Alao A, Brunner A, Willemsen TM, Chipeta K, Dardenne B, Dijksterhuis A, Wigboldus D, Eckes T, Six-Materna I, Expösito F, … Löpez WL (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 763–775. 10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales G, Przedworski J, & Henning-Smith C (2016). Comparison of health and health risk factors between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and heterosexual adults in the United States: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(9), 1344–1351. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KE, & Feinstein BA (2012). Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: An update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(2), 265–278. 10.1037/a0025424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstam J (1998). Transgender butch: Butch/FTM border wars and the masculine continuum. GLQ, 4(2), 287–310. 10.1215/10642684-4-2-287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. 10.1037/a0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved May 15, 2020, from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Henrichs-Beck CL, & Szymanski DM (2017). Gender expression, body–gender identity incongruence, thin ideal internalization, and lesbian body dissatisfaction. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(1), 23–33. 10.1037/sgd0000214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg AL, & Brallier SA (2009). An exploration of sexual minority stress across the lines of gender and sexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality, 56(3), 273–298. 10.1080/00918360902728517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn S (2007). Leaving lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students behind: Schooling, sexuality, and rights. In Wainryb C, Smetana JG, & Turiel E (Eds.), Social development, social inequalities & social justice (pp. 131–153). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL (2011). Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among sexual minority women. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 29(4), 403–435. 10.1080/07347324.2011.608336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Steffen AD, Wilsnack SC, & Everett B (2014). Lifetime victimization, hazardous drinking, and depression among heterosexual and sexual minority women. LGBT Health, 1(3), 192–203. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr D, Ding K, Burke A, & Ott-Walter K (2015). An alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use comparison of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual undergraduate women. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(3), 340–349. 10.3109/10826084.2014.980954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, & Stirratt MJ (2009). Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: The effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(4), 500–510. 10.1037/a0016848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff EA, & Landrine H (1995). The Schedule of Sexist Events: A measure of lifetime and recent sexist discrimination in women’s lives. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19(4), 439–70. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1995.tb00086.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff EA, Landrine H, & Campbell R (2000). Sexist discrimination may account for well-known gender differences in psychiatric symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24(1), 93–99. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01025.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, & Palmer NA (2012). The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network. [Google Scholar]

- Kury H, Chouaf S, Obergfell-Fuchs J, & Woessner G (2004). The scope of sexual victimization in Germany. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(5), 589–602. 10.1177/0886260504262967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA, Gibbs J, Manning V, & Lund M (1995). Physical and psychiatric correlates of gender discrimination: An application of the Schedule of Sexist Events. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19(4), 473–492. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1995.tb00087.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Norman SB, Means-Christensen A, & Stein MB (2009). Abbreviated brief symptom inventory for use as an anxiety and depression screening instrument in primary care. Depression and Anxiety, 26(6), 537–543. 10.1002/da.20471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Blayney J, Rhew IC, Lewis MA, & Kaysen D (2016). College status, perceived drinking norms, and alcohol use among sexual minority women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(1), 104–112. 10.1037/sgd0000142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Beckman KL, Chen JA, Simpson TL, & Williams EC (2019). Race/ethnicity and sexual orientation disparities in mental health, sexism, and social support among women veterans. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(3), 347–358. 10.1037/sgd0000333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, & Lambert AJ (2007). Toward a greater understanding of antigay prejudice: On the role of sexual orientation and gender role violation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29(3), 279–292. 10.1080/01973530701503390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, & Simoni JM (2011). The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(2), 159–170. 10.1037/a0022839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Molina Y, & Simoni JM (2012). Childhood trauma, adult sexual assault, and adult gender expression among lesbian and bisexual women. Sex Roles, 67(5-6), 272–284. 10.1007/s11199-012-0171-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, & Simpson TL (2014). Trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression among sexual minority and heterosexual women veterans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(3), 392–03. 10.1037/cou0000019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt HM, Gerrish EA, & Hiestand KR (2003). The misunderstood gender: A model of modern femme identity. Sex Roles, 48(3/4), 99–113. 10.1023/A:1022453304384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt HM, & Hiestand KR (2004). A quest for authenticity: Contemporary butch gender. Sex Roles, 50(9/10), 605–621. 10.1023/B:SERS.0000027565.59109.80 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt HM, Puckett JA, Ippolito MR, & Horne SG (2012). Sexual minority women’s gender identity and expression: Challenges and supports. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 16(2), 153–176. 10.1080/10894160.2011.605009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Derlega VJ, Clarke EG, & Kuang JC (2006). Stigma consciousness, social constraints, and lesbian well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 48–56. 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Mason TB, Winstead BA, Gaskins M, & Irons LB (2016). Pathways to hazardous drinking among racially and socioeconomically diverse lesbian women: Sexual minority stress, rumination, social isolation, and drinking to cope. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(4), 564–581. 10.1177/0361684316662603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Mason TB, Winstead BA, & Kelley ML (2017). Empirical investigation of a model of sexual minority specific and general risk factors for intimate partner violence among lesbian women. Psychology of Violence, 7(1), 110–119. 10.1037/vio0000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Milletich RJ, Mason TB, & Derlega VJ (2014). Pathways connecting sexual minority stressors and psychological distress among lesbian women. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services: The Quarterly Journal of Community & Clinical Practice, 26(2), 147–167. 10.1080/10538720.2014.891452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Pollitt AM, & Russell ST (2016). Depression and sexual orientation during young adulthood: Diversity among sexual minority subgroups and the role of gender nonconformity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 697–711. 10.1007/s10508-015-0515-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löpez G, & Yeater EA (2018, July). Comparisons of sexual victimization experiences among sexual minority and heterosexual women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Article 088626051878720. 10.1177/0886260518787202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Lee CM, Neighbors C, Larimer ME, & Turrisi R (2006). Do we learn from our mistakes? An examination of the impact of negative alcohol-related consequences on college students’ drinking patterns and perceptions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(2), 269–276. 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dermody SS, Cheong J, Burton CM, Friedman MS, Aranda F, & Hughes TL (2013). Trajectories of depressive symptoms and suicidality among heterosexual and sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(8), 1243–1256. 10.1007/s10964-013-9970-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Thoma BC, Murray PJ, D'Augelli AR, & Brent DA (2011). Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(2), 115–123. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, King KM, Stepp SD, Hipwell A, Smith H, Chung T, Friedman MS, & Markovic N (2012). Trajectories of alcohol and cigarette use among sexual minority and heterosexual girls. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(1), 97–99. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, & Boyd CJ (2010). The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 100(10), 1946–1952. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer RR, de Vries RM, & van Bruggen V (2011). An evaluation of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 using item response theory: Which items are most strongly related to psychological distress? Psychological Assessment, 23(1), 193–202. 10.1037/a0021292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]