Abstract

Ruthenium alkoxymethylidene complexes have recently come into view as competent species for metathesis copolymerization reactions when coupled with appropriate comonomer targets. Here, we explore the ability of Fischer-type carbenes to participate in cascade alternating metathesis cyclopolymerization (CAMC) through facile terminal alkyne addition. The combination of diyne monomers and an equal feed ratio of low-strain dihydrofuran leads to a controlled chain-growth copolymerization with high degrees of alternation (>97% alternating diads) and produces degradable polymer materials with low dispersities and targetable molecular weights. When combined with enyne monomers, this method is amenable to the synthesis of alternating diblock copolymers that can be fully degraded to short oligomer fragments under aqueous acidic conditions. This work furthers the potential for the generation of functional metathesis materials via Fischer-type ruthenium alkylidenes.

Ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) is one of the most powerful methods to construct diverse polymers containing numerous kinds of functional groups.1-9 Recent efforts have been directed towards advancing the backbone chemistry of metathesis-derived materials to incorporate labile functionality and control the sequence of the polymer backbone.10-19 To obtain the desired degradable materials using metathesis chemistry, a variety of new monomer scaffolds have been developed. Following classical bicyclic monomers design, Kiessling introduced an oxazinone system that could be degraded under aqueous acidic or basic media and easily modified to introducing fluorophores and bioactive epitopes.20,21 Entropy-driven ROMP also has granted access to degradable polyesters with near living precision.22 Statistical copolymerization strategies developed by Kilbinger,11 Johnson,23 and Xia24 have explored the ability to merge classical high-strain monomers with low-strain cyclic acetals and silyl ethers to impart ROMP systems with degradable linkages. As an alternative to commonly used highly strained cyclo-olefinic monomers, alkynes have found use in directing the ring-opening of low-strain rings to produce degradable materials.25,26 In this approach, the degree of degradation of the final polymers is directly related to the reactivity ratios of the monomer, with alternating systems being ideal.

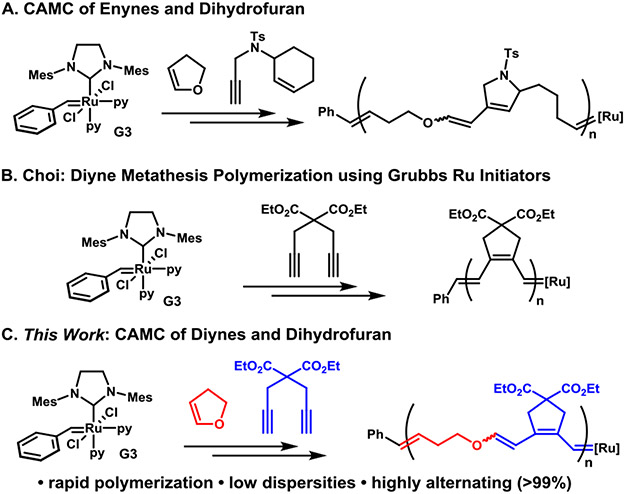

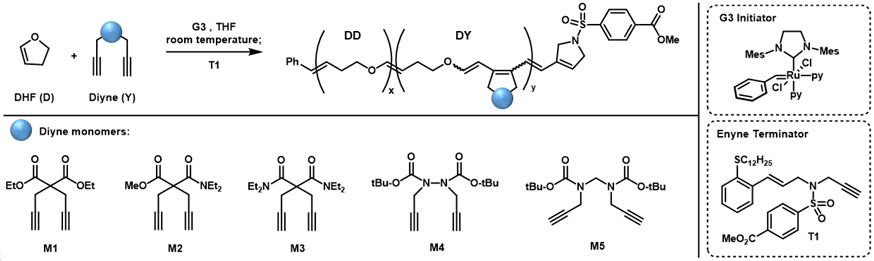

Recently, Xia and co-workers reported that the ROMP of electron-rich dihydrofuran (DHF) was viable and produced a poly(enol ether) that could be depolymerized back to monomer or hydrolyzed.27 The surprising reactivity of the Fischer carbenes in this method led our group to extend this insight to enyne monomers and develop an efficient alternating cascade metathesis polymerization with cyclic enol ethers (Figure 1A).28 In an even more dramatic example, Xia showed how copolymerization of DHF with even traditional norbornene monomers is highly efficient to create alternating copolymers.29 In all of these examples, the copolymers could be degraded into small molecules under acidic conditions.

Figure 1.

(A) Synthetic design for CAMC using enyne and cyclic enol ethers. (B) Diyne monomers for metathesis polymerization. (C) New synthetic design for CAMC using diyne and cyclic enol ethers.

Metathesis polymerization of diynes offers a versatile method for preparing functional polyacetylene derivatives. The first controlled living polymerization of diynes were demonstrated by Schrock and co-workers using molybdenum and tungsten catalysts with 1,6-heptadiyne monomers.30,31 They later modified these catalysts to obtain polyacetylenes in β-addition selectively.32,33 Buchmeiser and co-workers expanded this chemistry by identifying molybdenum systems that could give α-addition products exclusively.34,35 Most recently, Choi and coworkers demonstrated the synthesis of diverse polyacetylenes with user-friendly ruthenium catalysts that have control over α- or β-addition products (Figure 1B).5, 36-40 Given the ability of Fisher carbenes to efficiently react with terminal alkynes, we explored the ability of diyne monomers to participate in alternating copolymerization with dihydrofuran (Figure 1C).

The propagation rate of ynyne homopolymerization initiated with Grubbs third generation initiator (G3) is considerably slower than enyne homopolymerization. The polymerization of common 1,6 ynyne monomers reach full completion within 1 h, while that of enyne could be done in a matter of minutes or seconds.36,41 In the previously developed copolymerization of DHF and enyne monomers, the degree of alternation is limited by competitive enyne homopropagation. The lower rate observed for ynyne-systems was viewed as a benefit that may reduce the quantity of DHF needed in the feed while maintaining highly alternating behavior. To investigate the small molecule reactivity of diynes and enol ethers in metathesis processes, bis-ester diyne (M1, 50 eq) was reacted with an excess of ethyl vinyl ether (EVE, 500 eq) in the presence of G3 (1eq). After two hours at room temperature, M1 was cleanly converted into an enol triene without observation of any polymer or oligomer (Figure S7). This indicated that the homopolymerization of M1 was fully inhibited and suggested the viability of CAMC if combined with dihydrofuran (DHF).

To examine the cascade metathesis cyclopolymerization (AROMP) of diynes and dihydrofurans, bis-ester diyne monomer (M1) and dihydrofuran (DHF) were initially investigated (Table 1). Following our protocol for enyne substrates,28 G3 was added to a THF solution of M1 (0.5 M) and DHF (4.5 M) at room temperature with a diyne monomer to initiator (M:I) ratio of 20:1. To avoid the chain-transfer to active enol ether structures in the backbones, an efficient termination method using enyne terminator (T1) was utilized.42 The polymerization reached 82% conversion of M1 in 4 hours to give polymer P1 with a number average molecular weight (Mn) of 15 kDa and a dispersity (Ð) of 2.12 (Table 1, entry 1) according to size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). Despite the high dispersity of this resulting polymer, the 1H NMR spectrum contained distinct resonances for the backbone enol diene protons could be differentiated from DHF homopolymer and diyne homopolymer resonances (Figure S5). This analysis revealed the structure of P1 contained 85 % of alternating dyads (DY%) through comparison with the M1 homopolymer (Table 1, entry 1, Figure S5), with the remaining 15% comprised of DHF-DHF repeating units.

Table 1.

aPolymerization conditions: 3 μmol G3 catalyst and desired amount of DHF in THF, termination using 2 eq T1, DP (degree of polymerization) is the theoretical ratio of total amount of both monomers to the Grubbs initiator. bDetermined by 1H NMR in CDCl3. cDetermined by CHCl3 size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) calibrated using polystyrene standards. dCalculation of Mn, theo is based on alternating structures.

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry a | Diyne (Y) |

[M] (mol/L) |

Y: D | DP a | DY: DD b | Conversion b | Mn,SEC (kDa) c | Mn, theo (kDa) d | Ð c |

| 1 | M1 | 0.5 | 1: 9 | 40 | 85/15 | 82% | 15 | 6.1 | 2.12 |

| 2 | M1 | 0.5 | 1:1.2 | 40 | 97/3 | 83% | 9.1 | 6.1 | 1.38 |

| 3 | M1 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 40 | 98/2 | 86% | 8.2 | 6.1 | 1.24 |

| 4 | M1 | 0.05 | 1:1.2 | 40 | 99/1 | 82% | 8.5 | 6.1 | 1.24 |

| 5 | M1 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 100 | 99/1 | 88% | 16 | 15 | 1.45 |

| 6 | M2 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 100 | 99/1 | 87% | 15 | 16 | 1.38 |

| 7 | M3 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 100 | -- | <1% | -- | 18 | -- |

| 8 | M4 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 100 | 99/1 | 92% | 23 | 19 | 1.21 |

| 9 | M5 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 100 | -- | <1% | -- | 20 | -- |

| 10 | M4 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 20 | 99/1 | 93% | 4.4 | 4.1 | 1.21 |

| 11 | M4 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 40 | 99/1 | 93% | 11 | 8.1 | 1.22 |

| 12 | M4 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 200 | 99/1 | 91% | 38 | 37 | 1.45 |

| 13 | M4 | 0.1 | 1:1.2 | 400 | 99/1 | 89% | 48 | 75 | 1.61 |

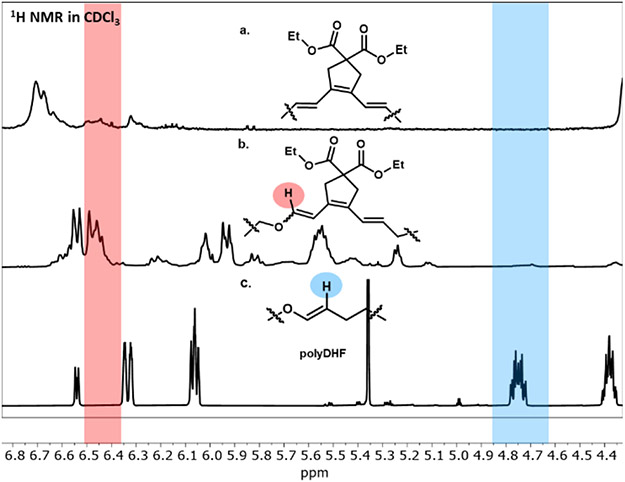

In order to suppress the homoaddition of DHF monomers and stabilize the propagating carbene, the diyne copolymerization was conducted at a lower temperature (0 °C). Unfortunately, the lower temperature reduced the overall polymerization rate significantly (Table S1, entry 4). Different Grubbs initiators were tested in this alternating copolymerization, though only G3 initiator displayed controlled behavior (Table S1, entry 1-3). Reducing the feed ratio of DHF surprisingly led to lower dispersities and higher alternation (Table 1, entry 2), and reduction in the overall monomer concentration produced additional increases to polymerization control (Table 1, entries 3-4). This led to optimized copolymerization conditions of 0.1 M in diyne with 1.2 equiv of DHF, and resulted in low dispersity polymers with almost entirely alternating structures (Table 1, entry 3). Analysis of the 1H-NMR spectrum led to the independent assignment of isolated M1-DHF diads (Figure S5 and Figure 2, red highlight, 6.4 ppm) and DHF-DHF diads (blue highlight 4.7 ppm), showing trace homopolymerization of DHF. Additionally, the 13C NMR revealed complete suppression of the oligo-diyne sequences in the obtained copolymers based on independently assigned ethyl group carbons on the polymer sidechains (Figure S6). Collectively, this data supports a very high degree of alternation without diyne homoaddition diads (>98% alternating dyads).

Figure 2.

1H NMR for polymers: a. polyM1, b. polyM1/DHF (1/1.2, 0.1 M of M1, RT), and c. polyDHF.

With the optimized reaction conditions established, CMAC of diyne monomers M2–M5 were evaluated with an ynyne-to-initiator ratio of 100:1. These derivatives vary with side chain or linker chemistry, and, interestingly, these features were found to play an important role in the success of the polymerization. While the mono-amide (M2) performed well to give an alternating copolymer in a high yield and low dispersity (Mn = 15 kDa, Ð = 1.38), bis-amide (M3) was completely resistant to copolymerization (Table 1, entries 6 and 7). Although not fully understood, this difference in reactivity may be caused by increased steric hindrance of the amide substituents, and a dimethyl amide analog led to the same result (Table S1, entry 6). The use of Boc-protected 1,7-diyne M4 gives a polymer with six-member ring rather than five-member ring in the backbone structures. It performed very well in copolymerization to give P4 with a targetable molecular weight of Mn = 23 kDa and much lower dispersity (Ð = 1.21) (Table 1, entry 8). While the shorter C─N bonds facilitate the ring-closing in this copolymerization, 1,8-diyne monomers (M5) did not copolymerize well, possibly due to the difficulty in cyclization for the medium-size ring (Table 1, entry 9).

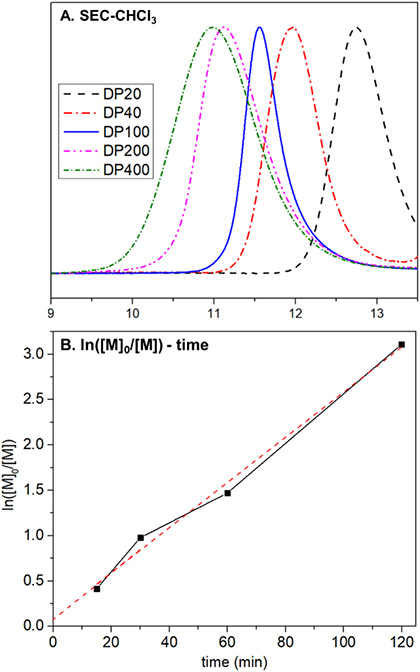

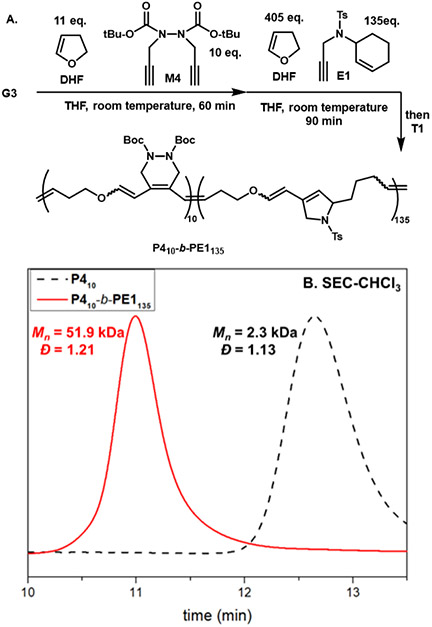

Given the performance of M4 and DHF in copolymerization, a series of molecular weights were targeted to probe the control of the polymerization. By changing the ratio of M4 to initiator, a series of polymers were obtained that possess low dispersities at high M4 conversions for DP (degree of polymerization) up to 100 (Figure 3A, Table 1, entries 8, 10-13). A slight increase in dispersity resulted (Ð = 1.45) when a degree of polymerization of 200 was targeted, presumably due to backbone chain transfer from reactive alkylidenes at high conversions or chain-end decomposition.43 Kinetic studies were also performed to determine the order of the polymerization (Figure 3B). By sampling and terminating the polymerization at different time points, a first-order kinetic profile for copolymerization of M4 and DHF was obtained. Given the living characteristics displayed in this copolymerization, alternating block polymers were prepared using diyne and enyne monomers (Figure 4). First, polymerization of M4 (10 equiv) with DHF (11 equiv) for 45 minutes was performed to give a living macroinitiator. E1 (135 equiv) with DHF (405 equiv) was then added to the reaction mixture for 90 minutes to give a P410-b-PE1135 diblock (Mn = 51.9 kDa, Ð = 1.21). The first block proceeded to high conversion of M4 (>95% by 1H NMR, Figure S9) and the chain-extension clearly shifted the elution peak to a lower retention time, suggesting highly living behavior of the propagating alkylidene.

Figure 3.

(A) SEC chromatogram of P4 at different targeted degrees of polymerization (DP) and (B) linear correlation of ln([M4]0/[M4]) with time.

Figure 4.

(A) Synthesis of diblock P410-b-PE1135 through sequential monomer addition and (B) SEC chromatogram of the first block and chain-extension.

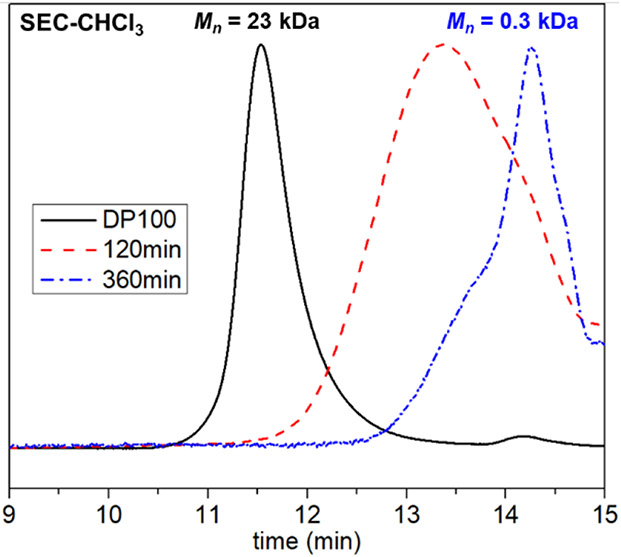

Due to the high degree of alternation in the polymer backbone, it was anticipated that these enol-containing copolymers could be hydrolyzed into small soluble fragments upon exposure to aqueous acidic conditions. To test the degradability, P4 was subjected to dichloromethane/water/TFA (1/1/1, v/v/v) mixtures, and aliquots were sampled at different timepoints for SEC analysis (Figure 5). Clear breakdown of the copolymer was observed at 120 minutes under these conditions, and complete degradation was reached within 60 hours. The observable shoulder at shorter elution times could arise from some degree of oligomerization of degraded products via condensation reaction. Although readily degraded under acidic conditions, P4 was found to be stable after one week in the solid-state at 0 °C and only slight changes to molecular weight and disparity after two weeks (Figure S18).

Figure 5.

Degradation of P4 in acidic condition in 2 hours.

To explore the thermal properties of these polymers, P4 was subjected to thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). While the TGA displayed 76% weight loss at 392 °C (Figure S11), DSC showed an endothermic transition at 125 °C (Figure S12) in the first cycle, which was not present in the second or third cycles. This uncommon heat exchange may be the result of Diels-Alder or ionic reactions occurring between the enol trienes moiety in backbones.44 To further study this behavior, a diluted solution of P4 was heated at 100 °C for 2 hours in toluene to promote intra-chain reactions and prevent cross-linking. No aldehyde peaks could be observed in 1H NMR of the obtained polymer, while changes were found in the olefinic region. Multiangle Light Scattering (MALS) characterization of the polymer before and after heating showed a reduction in polymer molecular weight and size for the new polymer (Figure S16). This leads to opportunities to develop new materials with thermally or hydrolytically triggered degradation.

In conclusion, a controlled polymerization of diynes and dihydrofurans has been developed that results in a highly alternating copolymer microstructure and employs nearly equivalent monomer feeds. The facile addition of ruthenium Fischer carbene with terminal alkynes enabled this CAMC and endowed the polymers with degradability. This work further demonstrates that ruthenium Fischer carbenes have significant potential towards the development of new chemoselective polymerization strategies for the design of new materials with degradability for bio-applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by start-up funds generously provided by the Georgia Institute of Technology and the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM133784. We acknowledge support from Organic Materials Characterization Laboratory (OMCL) at GT for use of the shared characterization facility.

Footnotes

No competing financial interests have been declared.

REFERENCE

- 1.Ogba OM; Warner NC; O’Leary DJ; Grubbs RH Recent Advances in Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 4510–4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutthasupa S; Shiotsuki M; Sanda F Recent Advances in Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization, and Application to Synthesis of Functional Materials. Polym. J 2010, 42, 905–915. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leitgeb A; Wappel J; Slugovc C The ROMP Toolbox Upgraded. Polymer. 2010, 51, 2927–2946. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callmann CE; Thompson MP; Gianneschi NC Poly(Peptide): Synthesis, Structure, and Function of Peptide–Polymer Amphiphiles and Protein-like Polymers. Acc. Chem. Res 2020, 53, 400–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang EH; Lee IS; Choi TL Ultrafast Cyclopolymerization for Polyene Synthesis: Living Polymerization to Dendronized Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 11904–11907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grubbs RB; Grubbs RH 50th Anniversary Perspective: Living Polymerization - Emphasizing the Molecule in Macromolecules. Macromolecules. 2017, 50, 6979–6997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Self JL; Sample CS; Levi AE; Li K; Xie R; de Alaniz JR; Bates CM Dynamic Bottlebrush Polymer Networks: Self-Healing in Super-Soft Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 7567–7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James CR; Rush AM; Insley T; Vuković L; Adamiak L; Král P; Gianneschi NC Poly(Oligonucleotide). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 11216–11219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Radzinski SC; Foster JC; Chapleski RC; Troya D; Matson JB Bottlebrush Polymer Synthesis by Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization: The Significance of the Anchor Group. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 6998–7004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pal S; Alizadeh M; Kong P; Kilbinger AFM Oxanorbornenes: Promising New Single Addition Monomers for the Metathesis Polymerization. Chem. Sci 2021, 12, 6705–6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker KA; Sampson NS Precision Synthesis of Alternating Copolymers via Ring-Opening Polymerization of 1-Substituted Cyclobutenes. Acc. Chem. Res 2016, 49, 408–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Moatsou D; Nagarkar A; Kilbinger AFM; O’Reilly RK Degradable Precision Polynorbornenes via Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem 2016, 54, 1236–1242. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pal S; Alizadeh M; Kilbinger AFM Telechelics Based on Catalytic Alternating Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 1396–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firat Ilker M; Bryan Coughlin E Alternating Copolymerizations of Polar and Nonpolar Cyclic Olefins by Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elling BR; Xia Y Living Alternating Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization Based on Single Monomer Additions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 9922–9926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu TW; Kim C; Michaudel Q Stereoretentive Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization to Access All-cis Poly(p-Phenylenevinylene)s with Living Characteristics. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 11983–11987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi T; Rutenberg IM; Grubbs RH Synthesis of A,B-Alternating Copolymers by Ring-Opening-Insertion-Metathesis Polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2002, 41, 3839–3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Park H; Lee H-K; Choi T-L Tandem Ring-Opening/Ring-Closing Metathesis Polymerization: Relationship between Monomer Structure and Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 10769–10775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Park H; Choi T-L Fast Tandem Ring-Opening/Ring-Closing Metathesis Polymerization from a Monomer Containing Cyclohexene and Terminal Alkyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 7270–7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song A; Parker KA; Sampson NS Synthesis of Copolymers by Alternating ROMP (AROMP). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3444–3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L; Li L; Sampson NS Access to Bicyclo[4.2.0]Octene Monomers to Explore the Scope of Alternating Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 2892–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan L; Parker KA; Sampson NS A Bicyclo[4.2.0]Octene-Derived Monomer Provides Completely Linear Alternating Copolymers via Alternating Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization (AROMP). Macromolecules 2014, 47, 6572–6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishman JM; Kiessling LL Synthesis of Functionalizable and Degradable Polymers by Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 5061–5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fishman JM; Zwick DB; Kruger AG; Kiessling LL Chemoselective, Postpolymerization Modification of Bioactive, Degradable Polymers. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 1018–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss RM; Short AL; Meyer TY Sequence-Controlled Copolymers Prepared via Entropy-Driven Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shieh P; Nguyen HV-T; Johnson JA Tailored Silyl Ether Monomers Enable Backbone-Degradable Polynorbornene-Based Linear, Bottlebrush and Star Copolymers through ROMP. Nat. Chem 2019, 11, 1124–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elling BR; Su JK; Xia Y Degradable Polyacetals/Ketals from Alternating Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Bhaumik A; Peterson GI; Kang C; Choi T-L Controlled Living Cascade Polymerization To Make Fully Degradable Sugar-Based Polymers from d-Glucose and d-Galactose. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 12207–12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yuan J; Giardino GJ; Niu J Metathesis Cascade-Triggered Depolymerization of Enyne Self-Immolative Polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60, 24800–24805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu L; Sui X; Crolais AE; Gutekunst WR Modular Approach to Degradable Acetal Polymers Using Cascade Enyne Metathesis Polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 15726–15730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feist JD; Xia Y Enol Ethers Are Effective Monomers for Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization: Synthesis of Degradable and Depolymerizable Poly(2,3-Dihydrofuran). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 1186–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sui X; Zhang T; Pabarue AB; Gutekunst WR Alternating Cascade Metathesis Polymerization of Enynes and Cyclic Enol Ethers with Active Ruthenium Fischer Carbenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 12942–12947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feist JD; Lee DC; Xia Y A Versatile Approach for the Synthesis of Degradable Polymers via Controlled Ring-Opening Metathesis Copolymerization. Nat. Chem 2021, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox HH; Schrock RR Living cyclopolymerization of diethyl dipropargylmalonate by Mo(CH-t-Bu)(NAr)[OCMe(CF3)2]2 in dimethoxyethane. Organometallics 1992, 11, 2763–2765. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox HH; Wolf MO; O’Dell R; Lin BL; Schrock RR; Wrighton MS Living Cyclopolymerization of 1,6-Heptadiyne Derivatives Using Well-Defined Alkylidene Complexes: Polymerization Mechanism, Polymer Structure, and Polymer Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 2827–2843. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schattenmann FJ; Schrock RR; Davis WM Preparation of Biscarboxylato Imido Alkylidene Complexes of Molybdenum and Cyclopolymerization of Diethyldipropargylmalonate To Give a Polyene Containing only Six-Membered Rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 3295–3296. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schattenmann FJ; Schrock RR Soluble, Highly Conjugated Polyenes via the Molybdenum-Catalyzed Copolymerization of Acetylene and Diethyl Dipropargylmalonate. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 8990–8991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anders U; Nuyken O; Buchmeiser MR; Wurst K Stereoselective Cyclopolymerization of 1,6-Heptadiynes: Access to Alternating cis-trans-1,2-(Cyclopent-1-enylene)vinylenes by Fine-Tuning of Molybdenum Imidoalkylidenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2002, 41, 4044–4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anders U; Nuyken O; Buchmeiser MR; Wurst K Fine-Tuning of Molybdenum Imido Alkylidene Complexes for the Cyclopolymerization of 1,6-Heptadiynes To Give Polyenes Containing Exclusively Five-Membered Rings. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 9029–9038. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang E-H; Yu SY; Lee IS; Park SE; Choi T-L Strategies to Enhance Cyclopolymerization using Third-Generation Grubbs Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 10508–10514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar PS; Wurst K; Buchmeiser MR Factors Relevant for the Regioselective Cyclopolymerization of 1,6-Heptadiynes, N,N Dipropargylamines, N,N-Dipropargylammonium Salts, and Dipropargyl Ethers by RuIV-Alkylidene-Based Metathesis Initiators. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang E-H; Kang C; Yang S; Oks E; Choi T-L Mechanistic Investigations on the Competition between the Cyclopolymerization and [2 + 2 + 2] Cycloaddition of 1,6-Heptadiyne Derivatives Using Second-Generation Grubbs Catalysts. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 6240–6250. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang C; Kang E-H; Choi T-L Successful Cyclopolymerization of 1,6-Heptadiynes Using First-Generation Grubbs Catalyst Twenty Years after Its Invention: Revealing a Comprehensive Picture of Cyclopolymerization Using Grubbs Catalysts. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 3153–3163. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jung H; Jung K; Hong M; Kwon S; Kim K; Hong SH; Choi T-L; Baik M-H Understanding the Origin of the Regioselectivity in Cyclopolymerizations of Diynes and How to Completely Switch It. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 834–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park H; Choi T-L Fast Tandem Ring-Opening/Ring-Closing Metathesis Polymerization from a Monomer Containing Cyclohexene and Terminal Alkyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 7270–7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu L; Zhang T; Fu G; Gutekunst WR Relay Conjugation of Living Metathesis Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 12181–12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jung K; Kim K; Sung JC; Ahmed TS; Hong SH; Grubbs RH; Choi TL Toward Perfect Regiocontrol for β-Selective Cyclopolymerization Using a Ru-Based Olefin Metathesis Catalyst. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 4564–4571. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shea KJ; Fruscella WM; Carr RC; Burke LD; Cooper DK Synthesis of Bridgehead Enol Lactones via Type 2 Intramolecular Diels-Alder Cycloaddition. New Intermediates for Stereocontrolled Organic Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109 (2), 447–452. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.