Abstract

Palliative care research is deeply challenging for many reasons, not the least of which is the conceptual and operational difficulty of measuring outcomes within a seriously ill population such as critically ill patients and their family members. This manuscript describes how Randy Curtis and his network of collaborators successfully confronted some of the most vexing outcomes measurement problems in the field, and by so doing, have enhanced clinical care and research alike. Beginning with a discussion of the clinical challenges of measurement in palliative care, we then discuss a selection of the novel measures developed by Randy and his collaborators and conclude with a look toward the future evolution of these concepts. Randy and his foundational work, including both successes as well as the occasional near miss, have enriched and advanced the field as well as (immeasurably) impacted the work of so many others—including this manuscript’s authors.

If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.

Lord Kelvin

Not everything that counts can be measured. Not everything that can be measured counts.

Albert Einstein

The challenges of measuring outcomes in palliative care contexts

Palliative care is a care philosophy, with deliberate attention by clinicians of all backgrounds on improving or maintaining the quality of life of patients with serious illness and their loved ones. Specialty palliative care is a multidisciplinary field of those with additional training, which aims to complement usual care providers during times of great distress or complexity. Palliative care interventions reflect this multidisciplinary care and may include efforts to manage symptoms using particular medications or therapies, alter communication approaches to enhance goal clarification, and support and guide the successful navigation of spiritual and cultural needs. As the term “palliative care” can be applied broadly and in most care settings, outcomes from interventions that modify or increase palliative care approaches span several stakeholders and domains.

A common question asked by those in the palliative care field is ‘How can we fully measure all the good things we do in our comprehensive, multidisciplinary, and multidomain practice—and do so when our patients face serious illness with often unavoidably poor outcomes?” The answer to this question for some time was not ideal. It was common to see trials that included outcomes such as hospital mortality, days of mechanical ventilation, and ICU length of stay. Although these outcomes are objective, easily retrievable from medical charts, and can be measured with little training, they clearly limit our ability to faithfully render the depth and complexity of palliative care’s impact—much like trying to reproduce a great painting with a quick sketch. The field has also struggled to detect pre- to post-intervention change, in part because of the relative coarseness or poor fit of some measures. These are critical gaps because if one can’t measure a phenomenon well, it’s difficult to demonstrably change it.

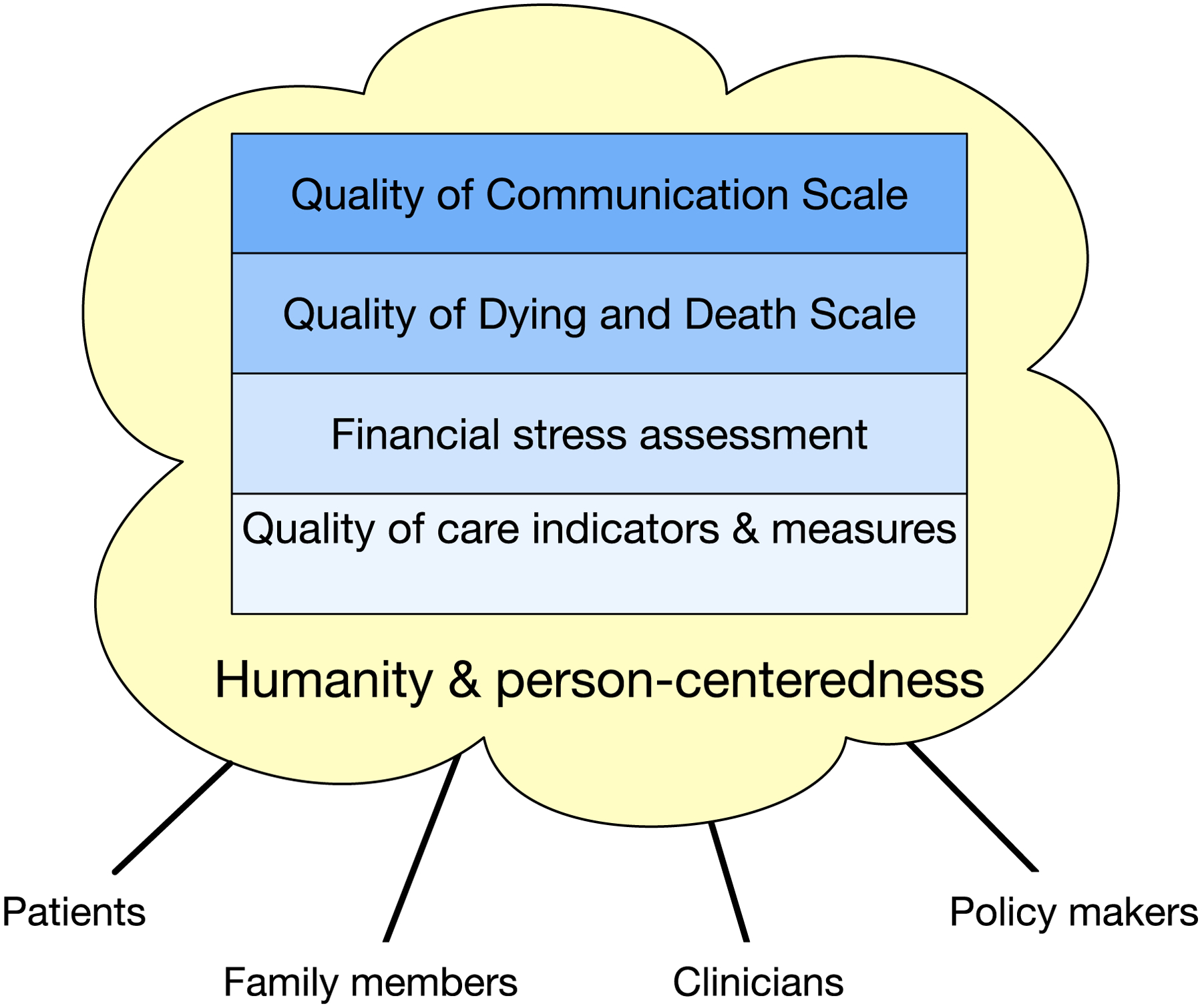

While it is worth noting that Randy himself has often commented on these challenges,1–3 he has also responded to them with an entire body of work. This quantitative and qualitative work has proposed theoretical models of mechanisms, expanded conceptual understandings of care processes, and developed novel surveys to faithfully capture person-centered outcomes relevant to the field (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

A snapshot of Randy Curtis’ measurement milestones and the context of their development

Outcomes work by Randy Curtis and colleagues

Quality of Communication

Background

Communication is the delivery mechanism for high-quality end-of-life and palliative care. In a sense, it is the syringe that delivers the palliative care intervention. Poor communication can lead to undesirable outcomes such as the receipt of goal-discordant care, increased psychological distress, and difficult bereavement.4,5 Conversely, good communication can enhance patient satisfaction, reduce family member distress, and facilitate shared decision-making.6,7

Yet in the late 1990s and early 2000s, much of the focus in outcomes measurement was on resource utilization and communication proxies such as length of stay, completion of advance directives, and clinician skills improvement. In 1995, the SUPPORT intervention with its focus on enhancing communication, failed to improve the likelihood of physicians’ understanding patients’ resuscitation preferences.8 Other work focused on shortcomings in communicating about prognosis and completion of advance directives. Although James Tulsky and colleagues had creatively defined methodological approaches to measuring communication quality in audio-taped conversations,9 few validated self-reported person-centered outcomes measures existed in the field that ‘examined the entire spectrum of communication’ as Marjorie Wenrich later described.10 To fill this gap, Randy partnered with Donald Patrick, Ruth Engelberg, and others on a series of studies that resulted in the development of the Quality of Communication (QOC) instrument which has since been used in numerous observational studies and clinical trials.11

The idea

The QOC story begins as many good things do in clinical research—by talking to patients and their clinicians. Just as highly active antiretroviral therapy was being introduced in 1997, Randy published a study conducted using focus groups among 47 patients with the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and their 19 physicians.12 They noted 29 barriers and facilitators to discussing end-of-life care, underscoring that ‘…the quality of communication about end-of-life care [was] one of the most important facilitators of [the end-of-life] discussion.’ The manuscript’s final paragraph noted that ‘it remains an unproven hypothesis that improving patient-physician communication about end-of-life care can improve the quality of the dying experience.’ How prescient. This statement foreshadowed not just the QOC and the Quality of Dying and Death instrument, but an entire school of thought—certainly in pulmonary and critical care medicine.

The beginnings of the QOC

The first version of the as-yet unnamed QOC derived from these focus groups was next evaluated among 57 patients with AIDS in 1999.13 At this point the QOC-to-be was a 4-item instrument assessing patients’ perceptions of their clinician’s knowledge of preferred treatment, willingness to listen, ability to give full attention to the patient, and caring about the patient as a person. At this stage, the pre-QOC had notable ceiling effects with most people rating each item with the most favorable response. While they observed an association between the instrument and clinicians’ knowledge of patients’ advance directives, there was no association with clinicians’ knowledge of patients’ treatment preferences. In what we choose to read as a moment of winking understatement, the authors admit that ‘measuring the quality of patient-clinician communication about end-of-life care is an important but difficult task.’

Expanding the conceptual model and adding content

So, the team returned to the drawing board in 2001. The task at hand was surely to figure out how to address the ceiling effects as well as more comprehensively capture more of the moving parts of the physician-patient interaction. Again using focus groups and qualitative analytical methods, they further explored what factors contributed to the quality of physicians’ end-of-life care among 79 patients with AIDS, cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).14 In addition to defining a conceptual model that has likely been reproduced in multiple National Institutes of Nursing Research grant applications, the authors described 55 components of physician skill contributing to quality end-of-life care organized into 12 separate domains. Some new additions included issues of competence, pain and symptom management, inclusion of the family, and emotional support. It is worth noting that some of these items were not more widely appreciated as mechanistic factors for nearly a decade and half after this publication. The paper concluded by noting that while the domains and model were novel and compelling, an evaluation of their usefulness was required. Data from this cohort was subsequently analyzed by patients’ disease process, with the predominant finding of substantial similarities in domains and components of physicians’ skills in providing good end-of-life care.15 However, some disease-specific differences existed such as COPD patients’ need for better education about their condition, AIDS patients’ worry about access to pain relief when many physicians has biases about addiction, and cancer patients’ concern with maintaining hope.

A companion focus group-based study was also published in 2001 with Marjorie Wenrich as lead author.10 Expanding the population to include 137 family members, health care professionals, as well as patients with chronic and terminal illnesses, the authors again aimed to determine which aspects of patient-physician communication were most important. They noted that the most important communication skills were ‘talking with patients in an honest and straightforward way and listening to patients’ as a process,’ a finding that ‘contrasted with the prevailing literature…focused on ‘techniques [that] tend [ed] to focus on bad news as a single event.’ This work is also noteworthy for its Discussion section’s commanding two-paragraph distillation of the multiple barriers to physicians’ effective communication with dying patients that still reads just as well two decades later. The research team returned to these data with a second publication in 2003 that reported on the importance to patients and family members of physicians’ ability to elicit and provide emotional support and personalized care—elements that ultimately became part of the QOC.16

The final QOC

In 2004, Randy and colleagues published the first exploration of the final QOC tested in a cohort of 115 patients with oxygen-dependent COPD.17 Drawing on the work described above, the team added 13 items to the original 4-item instrument. Each QOC item allowed responses from 0 (the very worst) to 10 (the very best) as well as ‘my doctor didn’t do’ or ‘don’t know’ (neither assigned a value). The 17-item QOC was scored by summing item scores and then transforming to a 100-point scale. Notably, in support of the QOC’s validity, correlations were generally high between the total score and items assessing general elements of communication (0.68), the overall care of the physician (0.52), and physician’s comfort discussing death (r=0.71). Furthermore, mean QOC scores were significantly higher among those with fewer depression symptoms. Although the mean item scores’ clustering in the 8–9 range on a 10-point scale suggested evidence of some ceiling effect, 8 of 17 items were scored ≤5 by at least 10% of respondents. It is also important to note that total scores did not reflect the high frequency with which patients reported the unscored ‘my doctor didn’t do’ option for including loved ones in discussions (37%), talking about my feelings (44%) and details (47%) about getting sicker, and asking about spiritual beliefs (83%) among others. This finding led to scoring changes in later versions. It is remarkable how persistent these same targets for intervention are nearly twenty years later,18 as are the group’s finding that QOC scores were not associated with any patient or physician characteristics.

In 2006, Ruth Engelberg, Lois Downey, and Randy published a comprehensive psychometric evaluation of the QOC using data from the 2003 and 2004 cohorts.11 Factor analysis suggested a stable two component solution composed of a 6-item general communication skills domain and a 7-item communication about end-of life care domain. Interestingly, transformed mean and median scores were high (~9) for the ‘general communication skills’ domain in comparison to those for the ‘communication about end-of-life care’ domain (~4). Evidence for convergent validity were shown through high correlations with similar constructs while discriminant validity analyses included the comparison of QOC domain scores to end-of-life reports and ratings. Note was again made of relatively high mean QOC scores akin to that often demonstrated by satisfaction measures that could limit the instrument’s responsiveness to detecting effects of future interventions. Despite these shortcomings, the QOC performed well as the only questionnaire assessing end-of-life communication quality with evidence of validity.

The legacy of the QOC

It is worth the reader’s reflection on the remarkably challenging process of transforming patients’ own words spoken in the moment to a final structured scale. To start, an entire decade elapsed between the initiation of patient recruitment for the initial focus groups and the QOC’s validation assessment. Although everyone grumbles about the quality of current outcomes measures, funding agencies are generally unwilling to support questionnaire development or improvement. The peer review process can become an interminable pitched battle of psychometric endurance.19 And to top it off, people still complain that the instrument has either too much floor or ceiling effect, is either too long or not comprehensive enough, and ‘is not hard enough’ an outcome compared to measures of death or ventilator-free days (the most frustrating complaint of all).

Yet the QOC is an innovative solution to an enormous clinical gap and a consistent success. It has proven reliable in assessing communication and consistently demonstrates strong associations with measures of similar constructs. At the time of writing, the QOC has been cited over 700 times, translated into a number of languages (e.g., Spanish, Vietnamese, Dutch, Portuguese, Korean), and demonstrated responsiveness in randomized trials.20–22 There is no question that the QOC will remain an enduring and important component of clinical research in the field of palliative care.

Quality of Dying and Death

Another substantial advance in palliative care outcomes measurement came in 2001 with the development of the Quality of Dying and Death (QODD) Questionnaire. Seemingly prescient to the evidence needs of the near future, Randy and colleagues identified that “a reliable and valid measure of the quality of the dying experience would help clinicians and researchers improve care for dying patients.”23

The conceptual model

In what we now recognize as a hallmark of their thoughtful work, Donald Patrick, Ruth Engelberg, and Randy began with a clear conceptual model of what they intended to measure. They first described the difference between three concepts relevant to the end of life: quality of care, quality of life, and quality of dying and death.24 While the first two factors tell us about medical care received near the end of life and how a person lives near the end of their life, the quality of dying and death tells us how a seriously ill person prepares for and experiences death. Recognizing the difficulty in engaging persons who are imminently dying, Randy and colleagues believed that it would be necessary to interview loved ones who bore witness to dying and the moment of death to determine how closely these experiences adhered to seriously ill loved ones’ preferences. They clearly differentiated their overall objective ‘to apply humanistic thinking and measurement principles to end-of-life experiences to obtain a summary measure that can be applied to populations’ from their expressed goal ‘not…to define all that dying means or might possibly mean as this can be known only to each person himself or herself or to demean any of the richness of life or the dying experience.’24

The measure

To understand perceptions of good and bad deaths as well as health states worse than death, Randy and colleagues reviewed the existing literature of after-death interviews with families and also conducted more than 200 interviews and numerous focus groups with healthy adults and patients with advanced AIDS, COPD, and cancer.24 The synthesis of data from this monumental effort became what we now recognize as the QODD Questionnaire, comprising 31 items in 6 domains: having control of symptoms and personal care, planning and engaging in important customs or events in preparation for death, spending time with family, having control of the moment of death, communicating treatment preferences, and addressing whole person concerns such as maintaining dignity and self-respect.24

In a validation study including 205 after-death interviews with families from a community-based sample of decedents, Randy and colleagues found that the QODD questionnaire demonstrated favorable psychometric properties.23 Specifically, they found no floor or ceiling effects, high internal consistency, and good construct validity as evidenced by significant associations with other markers of high quality care such as lower symptom burden and death in the location the patient desired. As a result, in a systematic review of measures of the quality of dying and death completed nearly a decade later, the QODD Questionnaire remained the most widely used and best validated among 18 total measures.25

The impact

Twenty years later, the QODD questionnaire continues to represent a cornerstone in the measurement of the dying experience. First, it allows clinicians, researchers, and policymakers to determine which processes of care lead to desirable outcomes such as improved quality of dying and death. For instance, in their validation study, Randy and colleagues confirmed that previously hypothesized factors such as communication with clinicians, accessibility of clinicians, and religious or spiritual considerations are key determinants of the quality of dying and death, whereas, contrary to prevalent beliefs even today, they found that intensity of medical care is not associated with quality of dying and death.23,26 Second, the QODD questionnaire accomplishes the difficult task of standardizing measurement of a highly heterogeneous outcome. For example, rather than making normative judgements about the value of dying at home or in hospital, the QODD simply asks if the individual died “in the place of one’s choice.” In this way, it allows us to reliably measure the quality of the moment of death while allowing for endless variation in individual preferences for location of death. Centering the patient as the unquestionable expert of their experience is an important lesson, and sine qua non of Randy’s research, that remains highly relevant as the field of patient-centered outcomes research continues to grow today.

Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that at the time of this writing, the two original QODD questionnaire development and validation manuscripts have been cited an astonishing 814 times,23,24 and the QODD has been adapted for use by various respondents in multiple languages and care settings. Beyond these impressive metrics, it is worth considering on a humanistic scale how the QODD has helped to improve the dying experience of countless seriously ill patients and their families, change how clinicians understand and attend to their patients who are nearing the end of life, and shape the careers of many palliative care investigators—and the overall trajectory of palliative care research.

Financial outcomes

Background

A decade-long debate between Randy and Gordon Rubenfeld, the best of friends, fueled the quest to rigorously investigate whether health care costs could be reduced by decreasing high intensity care provided near the end-of-life through palliative care interventions.27,28

Randy recognized that to ensure systematic change and sustainability of resources to support palliative care interventions, it was essential to engage hospitals, health systems and payers. To do this, exclusively addressing the quality component of the value equation would not suffice; investigating and measuring the potential for palliative care interventions to simultaneously reduce costs would also be needed.

Advancing the concept from a local to national level

Prior studies often assumed that reductions in total hospital or ICU costs and length of stay were always in the interest of hospitals and health systems. This overly simplistic view was fraught with problems. For example, hospitals must continue to pay direct-fixed and indirect costs irrespective of occupancy. This is especially pertinent in the ICU setting where 80% of costs are fixed and not easily modifiable.29 To bridge the gap between cost and utilization outcomes collected for research and fiscal metrics of particular value to hospital finance teams, Randy and colleagues recognized the need to engage with relevant stakeholders, including hospital administrators, finance teams, and economists. These discussions focused on recognizing and analyzing disaggregated costs (e.g. indirect costs, direct-fixed costs, and direct-variable costs) to better understand the economic impact of such factors as length of stay and unwanted ICU admissions.30 Randy and colleagues examined the potential for palliative care and advance care planning interventions to reduce costs using large administrative datasets and simulation methods.31 In one economic feasibility study, they found that adding a full-time communication facilitator trained to support ICU patients with serious illness and their families reduced both short-term (direct-variable) and long-term (total) health care costs even after accounting for the costs of the facilitator.32

Of course Randy’s efforts to examine the impact of palliative and supportive care interventions on costs were sometimes met with reluctance. Critiques included a sense that costs were not an appropriate patient-centered outcome and as such, some funding agencies (e.g., National Institutes of Health, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) did not find it within their purview. However, with time, persistence, changing cultural influences, and more evidence that palliative care interventions likely reduced costs for hospitals and health care systems, an increased recognition of the importance of examining both the quality and cost components of value-based care emerged.

Financial stress and its impacts on patients and families

Parallel to this work, a robust body of literature began to emerge describing the financial toxicity and stress of cancer care. Studies in this population provided compelling evidence that medical financial hardship for patients and families was associated with poor quality of life, higher symptom burden and psychological distress—all outcomes that are targets of palliative and supportive care interventions.33 This sparked great interest among this group and was the missing link to tie the exploration of financial outcomes back to improving the quality of care we provide seriously ill patients and their families.

Using data from a randomized trial comparing a coping skills training program and an education program for patients surviving acute respiratory failure and their families, Randy and colleagues found that financial stress was a key mediator in quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression for critically ill patients and their families.34 Currently, using both quantitative and qualitative methods, they are examining the various components of financial hardship (e.g. subjective and objective burden), the impact it has on patient- and family-centered outcomes for the seriously ill, and importantly, which aspects are potentially modifiable. Though often controversial due to concerns about the ability to modify financial hardship, it is likely that addressing this source of stress may be an important component of future palliative and supportive care interventions.

The future of outcomes measurement in palliative care

Randy’s contributions to envisioning, developing, and improving outcome measures to evaluate the care patients with serious illness and their families receive have enabled our field to advance the quality of palliative care. Whether these measures are self-reported surveys of patients, caregivers, or the bereaved, cost instruments, or electronic health record-based metrics, they have provided a foundation upon which to improve and enhance our approaches to outcomes measurement in a field that has struggled to faithfully render its profound impact.

One of the directions that Randy and his group have more recently identified and which holds promise for future measurement development is the use of latent variable modeling to develop and validate survey measures. No longer content with the use of exploratory factor and principal components analyses, computation of summary scores,35 and evaluation of the integrity of those scores with Cronbach’s alpha,36 the group has increasingly used latent variable modeling to assess the QOC and QODD.37,38 In 2013, Randy wrote an editorial for CHEST, noting numerous problems detected in the use of the QODD, including the fact that neither a single latent variable modeled with the full set of items as indicators nor five latent variables matching the domains proposed in the original QODD conceptual model provide acceptable fit to observed data.39 And although a 2010 article by the research group demonstrated the empirical fit of a four-domain QODD structure based on a subset of 13 of the original items in independent samples from two geographical areas that study’s use of the QODD questions as effect indicators of an underlying QODD construct now seems conceptually suspect.40 Movement in the research team’s most recent efforts with both the QOC and QODD suggest that the addition of a few questions that are unarguable effect indicators of a single underlying construct may assist in development of better measurement tools, using the original items as causal indicators of the construct.41

Another important future direction that builds on Randy’s work is the recognition of the highly individual aspects of patient and family experiences with serious illness and end-of-life that are assessed with measures like the QODD. The quality and relevance of end-of-life events and domains might be viewed in the light of ‘identities’ or ‘needs’—personal values and preferences as well as cultural and community identities that may not always be available to or easily articulated by families who are asked to describe these experiences.42,43 Exploring new ways to ask about these identities and needs that decedents have revealed to respondents during their lifetimes may be more accessible for family members than is information about specific preferences, and the incorporation of questions about identity could assist in the development of causal models. Similarly, families’ assessments of their loved ones’ needs (e.g., physiological, safety, love/belonging, esteem, self-actualization) and how well these needs are met at the end of life may contribute to a testable causal model for the quality of dying and death that will strengthen our ability to validly describe the individual’s experiences at the end of life and to measure whether interventions are able to alter and enhance those experiences.

Summary

Randy Curtis and his numerous collaborators have substantially advanced the science of outcomes measurement in palliative care through a consistently humanistic focus on the patient, the family member, and the provider. His work in measuring communication quality, quality of care delivery, quality of dying and death, financial stress, and other areas is indisputably innovative and undeniably boundary-crossing. This work has also allowed researchers and clinicians across the world to more easily understand the detailed impacts of palliative care interventions on the lives of those in their care. There is no doubt that Randy’s deep body of work and the compassion that motivated it will serve as both an enduring foundation and a consistent source of inspiration for future innovations in the field.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. Measuring success of interventions to improve the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. Nov 2006;34(11 Suppl):S341–7. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237048.30032.29 00003246-200611001-00008 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox CE, Curtis JR. Using Technology to Create a More Humanistic Approach to Integrating Palliative Care into the Intensive Care Unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Feb 1 2016;193(3):242–50. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1628CP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engelberg RA, Downey L, Wenrich MD, et al. Measuring the quality of end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage. Jun 2010;39(6):951–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. May 01 2005;171(9):987–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Apr 15 2005;171(8):844–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. Feb 1 2007;356(5):469–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slatore CG, Cecere LM, Reinke LF, et al. Patient-clinician communication: associations with important health outcomes among veterans with COPD. Chest. Sep 2010;138(3):628–34. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Investigators S A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA Nov 22–29 1995;274(20):1591–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Intern Med. Sep 15 1998;129(6):441–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Shannon SE, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med. Mar 26 2001;161(6):868–74. doi:ioi00562 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. Oct 2006;9(5):1086–98. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis JR, Patrick DL. Barriers to communication about end-of-life care in AIDS patients. J Gen Intern Med. Dec 1997;12(12):736–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell E, Greenlee H, Collier AC. The quality of patient-doctor communication about end-of-life care: a study of patients with advanced AIDS and their primary care clinicians. Aids. Jun 18 1999;13(9):1123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Understanding physicians’ skills at providing end-of-life care perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. J Gen Intern Med. Jan 2001;16(1):41–9. doi:jgi00333 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Patients’ perspectives on physician skill in end-of-life care: differences between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDS. Chest. Jul 2002;122(1):356–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Ambrozy DA, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ramsey PG. Dying patients’ need for emotional support and personalized care from physicians: perspectives of patients with terminal illness, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. Mar 2003;25(3):236–46. doi:S0885392402006942 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, Au DH, Patrick DL. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. Aug 2004;24(2):200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox CE, Ashana DC, Haines KL, et al. Assessment of Clinical Palliative Care Trigger Status vs Actual Needs Among Critically Ill Patients and Their Family Members. Jama Network Open. Jan 20 2022;5(1)doi:ARTN e2144093 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox CE, Donohue JF, Brown CD, Kataria YP, Judson MA. The Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire: a new measure of health-related quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Aug 1 2003;168(3):323–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1343OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM, et al. A Randomized Trial of a Family-Support Intervention in Intensive Care Units. N Engl J Med. Jun 21 2018;378(25):2365–2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Au DH, Udris EM, Engelberg RA, et al. A randomized trial to improve communication about end-of-life care among patients with COPD. Chest. Mar 2012;141(3):726–735. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, et al. Effect of a Patient and Clinician Communication-Priming Intervention on Patient-Reported Goals-of-Care Discussions Between Patients With Serious Illness and Clinicians: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. Jul 1 2018;178(7):930–940. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris K, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and death. Initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. Jul 2002;24(1):17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Evaluating the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. Sep 2001;22(3):717–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hales S, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Review: The quality of dying and death: a systematic review of measures. Palliative Medicine. 2010;24(2):127–144. doi: 10.1177/0269216309351783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashana DC, Chen X, Agiro A, et al. Advance Care Planning Claims and Health Care Utilization Among Seriously Ill Patients Near the End of Life. JAMA Netw Open. Nov 1 2019;2(11):e1914471. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luce JM, Rubenfeld GD. Can health care costs be reduced by limiting intensive care at the end of life? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Mar 15 2002;165(6):750–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Bensink ME, Ramsey SD. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: can we simultaneously increase quality and reduce costs? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Oct 1 2012;186(7):587–92. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1020CP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khandelwal N, Benkeser D, Coe NB, Engelberg RA, Teno JM, Curtis JR. Patterns of Cost for Patients Dying in the Intensive Care Unit and Implications for Cost Savings of Palliative Care Interventions. J Palliat Med. Nov 2016;19(11):1171–1178. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khandelwal N, Brumback LC, Halpern SD, Coe NB, Brumback B, Curtis JR. Evaluating the Economic Impact of Palliative and End-of-Life Care Interventions on Intensive Care Unit Utilization and Costs from the Hospital and Healthcare System Perspective. J Palliat Med. Dec 2017;20(12):1314–1320. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khandelwal N, Benkeser DC, Coe NB, Curtis JR. Potential Influence of Advance Care Planning and Palliative Care Consultation on ICU Costs for Patients With Chronic and Serious Illness. Critical care medicine. Mar 11 2016;doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khandelwal N, Benkeser D, Coe NB, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Economic feasibility of staffing the intensive care unit with a communication facilitator. Ann Am Thorac Soc. Dec 2016;13(12):2190–2196. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201606-449OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan RJ, Gordon LG, Tan CJ, et al. Relationships Between Financial Toxicity and Symptom Burden in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Journal of pain and symptom management. Mar 2019;57(3):646–660 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khandelwal N, Hough CL, Downey L, et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Financial Stress in Survivors of Critical Illness. Crit Care Med. Jun 2018;46(6):e530–e539. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNeish D, Wolf MG. Thinking twice about sum scores. Behav Res Methods. Dec 2020;52(6):2287–2305. doi: 10.3758/s13428-020-01398-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bentler PM. Alpha, Dimension-Free, and Model-Based Internal Consistency Reliability. Psychometrika. Mar 1 2009;74(1):137–143. doi: 10.1007/s11336-008-9100-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bollen KA, Bauldry S. Three Cs in Measurement Models: Causal Indicators, Composite Indicators, and Covariates. Psychological Methods. Sep 2011;16(3):265–284. doi: 10.1037/a0024448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bollen KA. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. John Wiley & Sons, 1989. ; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curtis JR, Downey L, Engelberg RA. The quality of dying and death: is it ready for use as an outcome measure? Chest. Feb 1 2013;143(2):289–291. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Downey L, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, Herting JR, Engelberg RA. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): empirical domains and theoretical perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage. Jan 2010;39(1):9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fayers PM, Hand DJ, Bjordal K, Groenvold M. Causal indicators in quality of life research. Qual Life Res. Jul 1997;6(5):393–406. doi: 10.1023/a:1018491512095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burke PJ, Owens TJ, Serpe R, Thoits PA. Advances in Identity Theory and Research. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zalenski RJ, Raspa R. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: a framework for achieving human potential in hospice. J Palliat Med. Oct 2006;9(5):1120–7. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]