Abstract

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, the Government of India imposed a nationwide lockdown of 21 days on May 25, 2020, which was extended thrice to a total of 68 days. Mandatory quarantine could hamper mental well-being, trust in the government, and compliance with guidelines. This study looks in-depth at individual accounts during the lockdown (phase A) and after the “unlock” (lifting of the nationwide lockdown; phase B) using telephonic interviews. Mass job loss and the exodus of migrant workers from major cities highlighted the need to include low-income groups in research; hence, purposive sampling was used. We interviewed 45 participants in phase A and 35 participants in phase B; the latter was drawn from the phase A pool based on availability and willingness. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis. Analysis revealed four themes of participants’ experiences, namely: (1) transitioning from a disrupted normal to a “new normal”; (2) accountability and lack of trust; (3) fear and uncertainty; and (4) perceived lack of control. Within the themes, coping with stressors was observed in six broad categories: (1) distraction, (2) escape/avoidance, (3) positive cognitive restructuring, (4) problem solving, (5) seeking support, and (6) religious coping. Results enabled the drawing of parallels and contrasts between various socioeconomic, religious, and sexual/gender groups and were discussed from the lens of cognitive appraisal theory and coping. The implications of these findings in psychological crisis intervention and policy are discussed, pointing toward the need to allow a collaborative effort and mutual trust to build a resilient society.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Lockdown in India, Longitudinal study, Psychological impact, Coping, Thematic analysis

In the light of the global pandemic of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by a virus named “SARS-CoV-2,” the Government of India imposed a 3-week-long lockdown on March 25, 2020 (Hebbar, 2020; The Hindu Net Desk, 2020). The lockdown was extended thrice to a total of 68 days with revisions in guidelines. Non-essential services and movement were restricted. The public was ordered to stay at home, follow social distancing, practice hygiene, and wear face covers. The lockdown was lifted, referred to as the unlock, in phases starting from June 1, 2020.

Research suggests that quarantine could be disturbing for those experiencing it, leading to symptoms of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anger, fear, and stress (e.g., Ferguson et al., 2021; Hawryluck et al., 2004; Rehman et al., 2022; Sharma & Subramanyam, 2020; Torales et al., 2020). Involuntary quarantine and ambiguous communication could hamper trust in the government (Barbisch et al., 2015) and reduce compliance to quarantine guidelines (e.g. Seale et al., 2020; Taylor-Clark et al., 2005). Misinformation or sensationalization by information sources (see Li et al., 2020) could hinder the effective management of health emergencies and amplify fear and panic (Rubin & Wessely, 2020; Patel et al., 2020; see Kilgo et al., 2019).

Researchers and health organizations have been asserting that the COVID-19 pandemic is exposing and exacerbating pre-existing socioeconomic inequities (e.g. American Psychological Association, 2020; Marmot & Allen, 2020). Poor representation of low-income groups in research could be detrimental for the Indian perspective, as the lockdown saw a large-scale loss of daily wage jobs, followed by a mass exodus of migrant workers from major cities, pushing people into deprivation (Iyengar & Jain, 2020). Those on the roads, mostly migrant workers, bore the brunt of police action (Dhar, 2020). While abundant studies look at the psychological impact of the pandemic in India, online tools such as self-report questionnaires become a barrier in reaching groups with poor educational or technological literacy—typically low-income groups (see Sharma & Subramanyam, 2020). The long-term psychosocial effects of involuntary quarantine after a mandatory lockdown is lifted also need to be investigated (Rubin & Wessely, 2020).

We aspired to understand the long-term impact of mandatory quarantine by exploring participants’ experiences, perceptions, and coping during the lockdown and after the unlock. Our inquiry was rooted in the theory of cognitive appraisal of stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), according to which people’s evaluation of an event becomes key in their outcomes. Individuals appraise events at two levels: primary and secondary. Primary appraisal involves assessing the relevance and impact of the event based on which it could be labeled irrelevant, positive, or stressful. For the same, we looked at the impact of the lockdown on participants’ daily routines, sleep, appetite, mood, emotions, behavior, and personal and professional relationships. We also looked at how the lockdown affected people’s functioning at home, work, or school. Aspects, such as sources of pandemic-related information and their effect, were covered in the interviews to know the perception of those experiences. Secondary appraisal is related to the available resources and options to deal with the stressor and one’s future expectations (Krohne, 2002; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Hence, we set out to understand how coping surfaced during the lockdown phase and changed in the unlock phase; and what expectations or concerns people had of the future. Whether participants viewed lockdown (or its consequences) as harm/loss, threat, or an opportunity for growth could give an understanding of their stress responses and well-being-related outcomes (O’Connor et al., 2010; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

To theorize coping with stress, we used the five-core coping families as described by Skinner and colleagues (2003): (1) distraction, (2) positive cognitive restructuring, (3) seeking support, (4) escape/avoidance, and (5) problem-solving. Following pilot interviews, we added a sixth coping category: religious coping. It was more useful to separate religious coping strategies from the other five as the former was particularly rooted in faith in God and religiosity; these were taken from the brief measure of religious coping (RCOPE; Pargament et al., 2011). Table 2 (under Result) contains a description of all the six coping categories.

Table 2.

Common coping strategies in response to stressors during the lockdown and unlock

| Coping/management | Description |

|---|---|

| Distraction | Coping passively by engaging in distracting activities rather than direct confrontation or problem solving (Allen & Leary, 2010) |

| Acceptance |

Accepting one’s situation and the lack of control and uncertainty attached to it “You can't keep dreading each and every day because you never know when this [lockdown] will extend. So, I have just accepted in my head that it is okay if it extends also.” (P12) |

| Consuming entertaining content | Consuming content for leisure or entertainment, such as watching TV, listening to music, and reading |

| Creative expressions | Articulating thoughts and feelings through creative channels, such as scribbling, practicing music, and writing |

| Meditation | Using meditation techniques, such as mindfulness, to disengage with the stress or negative emotions accompanied by a situation |

| Physical activities | Physical exercises or activities to keep fit or busy such as, yoga, walking, and boxing |

| Scheduling | Planning and following a routine of daily activities to “keep busy” and minimize unplanned space in a day |

| Positive cognitive restructuring | Coping by viewing one’s stressors from a positive outlook by overemphasizing positive aspects, de-emphasizing negative aspects, or thinking positively in general |

| Downward comparisons | Reframing one’s situation by making comparisons to people who are perceivably doing worse off financially, physically, emotionally, or socially. For e.g., “at least I have family support. People who are living alone must be suffering more.” (P01) |

| Hope | Talking about one’s future with hope or expectation of eventual positive outcomes. E.g., “[What keeps me going is] the thought that I will be able to get work again once the lockdown is lifted.” (P37) |

| Positive inferences | Drawing out positive inferences out of a neutral or negative event. For example, “[getting laid off from work] is good for me. I will stay at home and stay safe.” (P24) |

| Seeking support |

Being around or interacting with family, friends, acquaintances, pets, and other people “Connecting with your friends, your family members, talking to them is one thing that keeps us, me in particular, socially connected. Just physically disconnected.” (P19) |

| Escape/avoidance | Attempting to avoid a stress-inducing thoughts or events or reducing engagement with them |

| Avoiding institutions and people | Avoiding confrontation or encounters with institutions, such as healthcare and police, and with other people beyond the reasons of physical distancing, say, to avoid mistreatment, stigma, antipathy, and violence |

| Avoiding negative information or thoughts | Escaping or reducing exposure to information or thoughts that could be overwhelming or stress-inducing |

| Waiting it out | Passively waiting for a stressful event to pass by itself, such as the lockdown or phase of unemployment due to lockdown |

| Problem solving | Direct confrontation of the problem that can be correct or negative effects of which could be minimized |

| Controlling consumption | Cutting down on or increasing consumption of available resources in response to financial distress or insecurity, for example by “adding fewer ingredients in meals” (P28) |

| COVID-related preventive behaviors | Voluntarily engaging in desirable health behaviors for preventing infection and spread of coronavirus disease. For example, physical distancing, hand-washing, wearing face masks, etc |

| Helping behavior | Proactively helping people who one expects to be in distress in response to financial or empathy-related stress |

| Online activism | Making efforts to generate awareness about socio-political issues through online channels with the intention of reform |

| Replanning or resuming delayed plans | Planning life events again in the context of the pandemic or resuming plans delayed due to lockdown, such as weddings or travel |

| Seeking precarious work | Looking for precarious or low-paying work in response to unemployment and financial distress |

| Self-treatment | Seeking treatment for one’s physical or psychological symptoms without consulting a health practitioner, by searching information online, practicing remedies, or taking over-the-counter medicines |

| Religious copinga | Using religion, religious beliefs, and religious practices to cope with stress |

| Religious methods of coping to find meaning | Redefining stressor in context of religion |

| Religious methods of coping to gain comfort and closeness to God | Focusing on religion through faith-based rituals such as praying, fasting, reading religious text |

| Religious methods of coping to gain control |

Collaborative religious coping: believing that the situation could be solved through collaboration with God, as long as they also do their part; gratitude towards God Passive religious deferral: expecting a higher being, i.e., God, to take control of one’s situation (Pargament et al., 2011) |

Method

Participants

The sample included people aged 18 years or older and residing in India during the lockdown. Exceptions to the lockdown rules (e.g. essential service workers or other professionals commuting to their work throughout the lockdown) were out of the scope of the study. Social media advertisements (Facebook and LinkedIn) and word-of-mouth were combined to recruit participants. Participants were, at least, second-order contacts. Purposive sampling allowed for greater inclusivity in terms of occupation and socio-economic background.

We interviewed 45 participants during the lockdown (phase A) and 35 participants after the unlock (phase B). Among phase A participants, 15 were female and 28 were male; four identified as non-binary and other gender or sexual minorities (mean age = 34.45 years, SD = 13.06, years). All 17 participants from the low socioeconomic status (SES) group worked precarious jobs spread out among Skill level I and Skill level II occupations and were out of work due to the lockdown. Majority of the participants reported Hinduism (n = 28) as their religious background, while Islam also accounted for a substantial portion of the sample (n = 15). One individual reported Buddhist religious background and one was unspecified. The term religious background is used over “religion” to include non-religious or non-practicing participants, as their background religion was important in certain experiences. In phase B, 35 participants (mean age = 32.71, SD = 10.53, years) were interviewed from the pool of participants in phase A based on willingness and availability. Ten were female; 23 were male; and three identified with other sexual or gender identities. Twelve out of the 13 participants from the low SES group remained out of work in phase B. Proportions based on religious background were similar to phase A (Hinduism = 22, Islam = 11, Buddhism = 1, Non specified = 1, n). Table 1 represents the socio-demographic details of the participants.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic details of the participants

| Participant characteristics | Phase A | Phase B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender and sex-related informationa | ||||

| Female | 15 | 33.33 | 10 | 28.57 |

| Male | 28 | 62.22 | 23 | 65.71 |

| Non-binary and other gender/sexual minorities | 4 | 8.89 | 3 | 8.56 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | 7 | 15.56 | 6 | 17.14 |

| 25–34 | 17 | 37.78 | 14 | 40 |

| 35–44 | 14 | 31.11 | 11 | 31.43 |

| 45–54 | 3 | 6.67 | 2 | 5.71 |

| 55–64 | 2 | 4.44 | 2 | 5.71 |

| 65 + | 2 | 4.44 | 0 | 0 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | ||||

| Low | 17 | 37.78 | 13 | 37.14 |

| Mid to high | 28 | 62.22 | 22 | 62.86 |

| Religious background | ||||

| Hinduism | 28 | 62.22 | 22 | 62.86 |

| Islam | 15 | 33.33 | 11 | 31.43 |

| Buddhism | 1 | 2.22 | 1 | 2.86 |

| Not specified | 1 | 2.22 | 1 | 2.86 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Home-makers | 4 | 8.89 | 3 | 8.57 |

| Full-time student | 8 | 17.78 | 7 | 20 |

| Skill level I (elementary occupations, e.g., laborers, domestic workers, cleaners) | 8 | 17.78 | 5 | 11.11 |

| Skill level II (skilled trade occupations, e.g., tailors, farmers) | 8 | 17.78 | 6 | 13.33 |

| Skill level III (associate professionals, e.g., clerks, religious associates, event organizers) | 7 | 15.56 | 5 | 11.11 |

| Skill level IV (professionals, e.g., teachers, engineers) | 9 | 20 | 9 | 20 |

| Workers not classified by occupations (e.g., escort service workers) | 1 | 2.22 | 0 | 0 |

N = 80 (nA = 45, nB = 35). Participants were on average 34.45 years old in phase A (SD = 13.06) and 32.71 years old in phase B (SD = 10.53)

aIncludes intersectionalities between gender identity and sexual orientation

bOccupations were coded according to the National Classification of Occupations by the Government of India, Ministry of Labour & Employment (National Career Service, 2015)

Data Collection

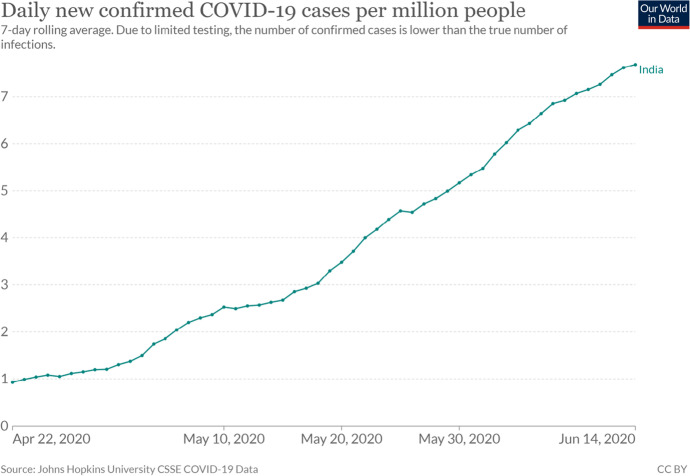

We utilized semi-structured, in-depth interviews of individuals about their experiences and perceptions during and after the nationwide lockdown in India. A third researcher, not part of the main study, took seven interviews during the lockdown and added value to early discussions. The study was conducted in two phases. Phase A was conducted during the lockdown from April 22, 2020, to May 10, 2020, with 45 participants (nA = 45). They were coded as Px, x being a two-digit number from 01 to 47 based on the chronology of their interviews in phase A (P17 and P36 dropped out). Phase B was conducted after the unlock from June 7, 2020, to June 14, 2020. Participants (nB = 35) in the second phase were drawn from the pool of phase A participants based on their availability and willingness for a second interview. Figure 1 illustrates a graph of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the period of data collection.

Fig. 1.

An image of the graph of confirmed COVID-19 cases per million people in India from April 22, 2020 to June 14, 2020. Note. Image downloaded from OurWorldinData.org (Ritchie et al., 2020). Graph represents the combined phases (phase A and phase B) of data collection

Our interview guide (attached as Appendix) with open-ended questions was based on available literature on stress and discussions among the authors and two external researchers. It was piloted on two participants not included in the study sample and was modified accordingly. The interviews were telephonic and approximately 1 h long each (range of phase A interview length = 0:14:47 to 2:24:22, mean = 0:50:53; range of phase B interview length = 0:29:57 to 1:57:43, mean = 0:58:24; hours:minutes:seconds). After the participants provided consent, interviews were audio-recorded. The encrypted audio files were transcribed by university students, who were trained and compensated for the work. The researchers then verified and edited the transcriptions to correct errors and gaps. Interview languages were Hindi, English, or both. The English parts of interviews were presented verbatim, and the Hindi parts were translated.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were uploaded on a web application, Dedoose, for thematic analysis. The thematic approach delineated by Coffey and Atkinson (1996) was used for analysis. Adopting a pragmatic approach, we first used interview templates to generate open, primary codes, e.g., “sleep,” “appetite,” “routine,” “mood/emotions/feelings,” “work or school-related,” “personal relationships,” “any medical history,” “major events,” “sources of information.” Second, codes were added, connected, revised, or reduced as per the interview data by hand and in Dedoose. This process of analysis was carried out until saturation of significant themes was achieved in each phase. We analyzed the data, first independently, and then collaboratively. New codes were defined with examples within Dedoose for the other coder, and then they were discussed after every few sets of interviews. The preliminary themes and interpretation were discussed with two external researchers with access to our Dedoose accounts. The manuscript was reviewed by the Technical Review Committee at the first author’s workplace, and the critiques and concerns were discussed in person with the committee members. Preliminary results were also presented at a national conference as a poster for expert feedback.

The interview notes were summarized to participants at the end of each interview to check researchers’ understanding. Major interpretations of the first interview were verified with the participants in the second interview. Five participants were called for a follow-up after the second interview for respondent validation (Birt et al., 2016).

Ethical Considerations

The procedures in the study followed the ethical standards of APA and the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained prior to the conduction and recording of the interviews. The participants understood that they could withdraw at any point in time and were given points of contact for follow-up. We encrypted identifying or sensitive information in interview audios before sending them for transcription. Describing potentially stressful accounts could leave participants vulnerable to negative emotional outcomes. Hence, all the participants were given lists of volunteering mental health professionals compiled by the Rehabilitation Council of India (RCI, 2020) and Queer Affirmative Counselling Practice (QACP) certified practitioners by Pink List India (2020). Due to non-funding, only the participants indicating lower socioeconomic status (SES; 17 participants) were compensated—with a sum of 1000 Indian Rupees1 each.

Results

The analysis of 45 interviews in the first phase and 35 interviews in the second phase revealed four themes representing the broad experiences of the sample: (1) transitioning from a disrupted normal to a “new normal,” (2) accountability and lack of trust, (3) fear and uncertainty, and, (4) perceived lack of control. The themes describe participants’ overarching experiences of the lockdown in each phase within which stressors and coping interact. Coping was observed and categorized from the lens of the models by Skinner et al. (2003) and Pargament et al. (2011). The broad coping families were observed in both phases but differed in manifestations depending on the change or persistence of stressors. Table 2 describes coping strategies observed in this study. It is to note that coping strategies employed by the study participants may or may not be healthy, desirable, or lead to positive outcomes.

While every participant was not cited, all of them are represented in the following themes.

Theme 1: Transitioning from a Disrupted Normal to a “New Normal”

Phase A was accompanied by various immediate changes directly due to the lockdown or due to the disruptions caused by it. All the participants indicated certain changes in their pattern and quality of daily routine, sleep, and appetite immediately after the lockdown, if not throughout. Lockdown created a lot of unstructured time that would lead to monotony and stress. After the unlock, phase B saw some reversal in routines, but mostly exhibited adjustment to a new normal or prolonged effects of the lockdown.

Phase A: Lockdown Creating Disruption and Unstructured Time

As a direct result of home quarantining and social distancing, a substantial number of people reported “monotony” (P05, female, in her 40 s, mid-to-high SES), saying that their “life had stopped” (P11, male, in his 40 s, mid-to-high SES). P27 (female, in her 20 s, mid-to-high SES), a college student, said, “It’s a self-imposed pressure that I have this entire day before me; I need to do something productive today. That’s literally my first waking thought.” Unstructured time and monotony were often dealt with by engaging in activities and hobbies to distract oneself from the distress associated with the disruption caused by the lockdown. The participants often spoke about “practicing gratitude” (P19, female, in her 20 s, mid-to-high SES), “mindfulness” (P42, male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES), and “yoga and meditation” (P47) to cope with distress. Many others resorted to passively consuming entertaining content. P02 (male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES) reported a lack of motivation and reduced physical activity, saying, “I work on auto-pilot. Watch another series, an episode, another episode. There is no reason to get up anyway.”

Having and engaging with social relationships was a protective factor for most participants and also a way of coping with isolation and monotony. P24 (male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES) said, “Whenever I go for my evening walk, I talk to my friends on the phone.” Others engaged in religious activities, such as “praying and reading” religious texts (P30, female, in her 40 s, low SES) to distract from loneliness and stress. Having something to look forward to was also a way of distraction. P15 (male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES) said, “I have defined a time schedule for the whole day. […] I don’t feel low because my schedule is tight.” “Waking up for the pre-dawn meal [during Ramadan],” “farming” (P25, male, in his 60 s, low SES), or scheduling a “regular workout” (P18, female, in her 20 s, mid-to-high SES) were other activities that gave participants something to look forward to.

Regular income was discontinued, reduced, or delayed for most participants or the primary earners of their families. All the respondents engaged in precarious work reported job loss. Difficulties in financial adjustment led to participants “reducing daily expenditure” (P44, male, in his 40 s, low SES).

Several participants reported interruption of access to basic needs, urgent care, and social support. Ten participants, mostly from the low SES group, reported being stranded in a place away from their hometown because of the lockdown, hindering accessibility.

[We] cannot get to a hospital, cannot book an auto[rickshaw] or cab. My wife is pregnant—it is her seventh month—we are taking her to a government dispensary for check-ups. The private dispensary where she was getting check-ups earlier is too far to walk to. [...] She had to get a vaccine shot but that could not happen. [...] If I were in my hometown, things would have been easier, as I know people there. (P39, male, in his 20s, low SES)

P37 (male, in his 40 s, low SES), a daily wage painter unemployed after the lockdown, said,

Now that I don’t have work anymore, I don’t get drowsy [...] I think a lot... ‘What should I do?’ [...] Sometimes I nap for half an hour but I barely sleep. [...] My wife often nags me for not buying something in advance when we have a food shortage. I have headaches thinking about how to arrange for ration [grocery].” (P37)

Feeling financially and psychologically unprepared for the lockdown caused psychological distress and bodily responses such as fatigue, lethargy, and “body pain” (P46, female, in her 60 s, low SES). P34 (female, in her 20 s, mid-to-high SES), a trans woman and an escort service worker said,

You know, we [transgender people] are not born the way we wanted to be… our expenses on medicine, our expenses on laser treatment and this and that [...] Moreover, right before the lockdown I just got implants done—literally, I’m—like—exhausted, I had no clue this was coming but it's more stressful because of that. [...] And lots of pressure for rent [...] My coping mechanism is my dog [...] If he wasn’t there I would have gone mad. (P34)

The participants reported self-treating physical and psychological symptoms. P14 (male, in his 30 s, mid-to-high SES) said, “I have withdrawal symptoms of [cigarette] smoking—headaches, nausea, irritation, depression. […] I have knowledge about medicines so I take medicines for it. […] And I search on YouTube [a video hosting website] for videos of psychologists talking about depression.”

Many participants reported being worried about the effects of lockdown disruptions and trauma on others, perhaps, i.e., experiencing empathy-based stress. While most of the time, these “others” were family members and friends, sometimes they were strangers.

I have running thoughts, not for myself, but for the poor… like our maids, laborers—how are they managing, if they are getting food to eat. I have a soft corner for them [...] So I feel a lot for poor people, [stray] animals—dogs, cows. I make rotis2 for puppies. (P03, female, in her 40s, mid-to-high SES)

Among low-SES participants, helping behavior seemed to be a general response to collective struggle. P29 (male, in his 30 s, low SES), who depended on his workplace for food, said, “I give away one food packet every day to my neighbor… they don’t even have access to food.”

For several individuals, the lockdown was a break from the demands of daily life. The work-from-home setup allowed for a certain level of freedom. P18, a private tutor, “I prefer [conducting] online classes rather than traveling [to classroom locations]. I can be around my family more.” P42 said, “I deliver the same amount of work [working from home] as I did at the office.” Having enough “free time for hobbies” (P15) and other desired activities allowed participants to see lockdown as “a chance to work on self and do some self-reflection” (P02). Some participants reported, “improved quality of sleep” (P24) and healthier, “home-cooked meals” (P20, male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES).

Apart from a lot of deaths, I am very happy that this lockdown happened. I am not facing any issues. [...] I got a sudden break. It was like a surprise gift. I am enjoying this time, everyone is. Unless someone is not getting food to eat. [...] I am able to prepare [academically]. Some of my friends have internet problems but I don’t. (P16, male, in his 20s, mid-to-high SES)

While lockdown was viewed as an opportunity to spend “more time with family” (P01, female, in her 40 s, mid-to-high SES), this was a stressor for gender and sexual minorities and for participants with a history of abuse at home; particularly as interaction with friends and dating opportunities reduced.

My uncle would sexually abuse me when I was younger… and my family did nothing about it [...] Due to the lockdown I am stuck with my family for much longer than I am used to. And he [uncle] still lives in this house. It is stressful to be in the same space as him. (P45, non-binary, in her 20s, mid-to-high SES)

For P38 (non-binary, in their late teens, mid-to-high SES), engaging in creative expressions was a way of dealing with anxiety caused by living with their family.

I went on one date but then the lockdown happened. [...] We texted but nothing happened. Just texting did not help. [...] Most of the time—before the lockdown—I was out of home, in college. I am a different person at home. I was a more outspoken person in the world but at home I reserve myself. [...] There are issues, conflicts with my family. [...] Sometimes I scribble randomly. It helps me forget whatever made me anxious. (P38)

Phase B: Readjusting to the “New Normal” and Feeling Left Behind

Phase B saw a conversation around the “new normal” as people had to readjust to their old routines or incorporate new, semi-permanent changes to their routines.

Only a handful of participants said that their “life [was] getting back to normal” (P13, male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES) as their pre-lockdown schedule resumed. P03 reported recovering financially, “[My husband] is getting [building] contracts now… Although, it’s not at the same rate.” P11’s job insecurity dissipated as he started going “back to the office” and “received a regular salary.” And, P39 had secured “contract work” and was in a “good [or better] mood” after the unlock (P39). Additionally, external financial aids (by relatives, acquaintances, volunteers, non-government bodies, and government bodies) reportedly helped in transitioning to the new normal. P23 (male, in his 50 s, low SES) said, “Your assistance [research compensation] of Rs. 10003 benefited me a lot.” Transitioning was also easier for those who could structure their time. For example, P15 continued to “keep a schedule” for each day that helped him “not get stressed.”

Many participants described difficulties in readjusting to pre-lockdown routines. P42 said, “The place where I live is a containment zone. It is quite far from my workplace. So it will be really difficult for me to commute”—considering not many public modes of transport were operating. For P29, it was difficult getting back to laborious work after a long period of inactivity as “it had become a habit to keep lying on the bed.”

My husband has started going to the office again, so now I sleep on time. [...] But for two and a half months we spent 24 hours together. Now he [her husband] is at work for eight hours a day. So it gets lonely. It will take some time to get used to that routine again. (P01)

Most participants asserted that either their life had not changed from the way it was during the lockdown, or that the change was a “new normal” (P26, female, in her 20 s, mid-to-high SES), different from pre-lockdown times. Commonly, this new normal was about getting accustomed to COVID-related behaviors, such as frequent hand washing, sanitizer use, wearing protective gear, especially masks, and maintaining social distance. Some said that “getting used to this weird way of living will also take some time” (P45). P14 said, “People believed that COVID would end after the lockdown. It is false optimism.”

Mostly [I am] just anticipating when things will get back to normal. Just the simple pleasures of going out without repercussions and without having to think that “oh!” when I go out and “I have to take a shower now” when I come back, these little things, you know? (P27)

Engaging in COVID-related behaviors helped adjust to the new normal and were positive habits that some participants wanted to continue in the future.

Few things like consciously not touching people; I think this is a good habit even without lockdown. And I feel to [sic] continue after this scenario goes away. Because I feel we Indians generally ignore the personal spaces of individuals. (P13)

Some approached the new normal with acceptance. P15 added, “We have to learn to live with it [the coronavirus].” The participants started to normalize or avoid the stress associated with the pandemic and lockdown. P02 said, “It’s [COVID-19 cases] just numbers for me now. Like the prices of petrol and diesel.” P24 said, “I stopped looking at it [COVID-19 cases]. It is normal now.” According to the participants, this normalization was reflected in the “[reduced] coverage of corona in the news” (P22, male, in his 30 s, low SES) and “less conversation of coronavirus with others” (P29). Many believed that “people [were] more aware now,” which was also why there were “less [sic] fake messages on WhatsApp” about COVID-19 (P03).

The participants were learning to adjust to stressful situations using distracting coping techniques, such as creative expressions. P38, for whom living with family was a source of stress, said, “I am getting used to [living with family]. […]I would articulate the [stressful] thoughts or bring the thoughts onto the paper.” Strategies such as meditation and mindfulness were “difficult to be regular at” (P02), so participants would only meditate “when there [was] high stress” (P05).

For most participants, interacting with family, friends, and neighbors remained a supportive factor. P28 (female, in her 30 s, low SES) said, “Sometimes neighbors sit with me and we chat… talk about something good. Then I forget all the problems.” Some participants took upon a problem-solving strategy by resuming plans interrupted by the lockdown, such as marriage and travel.

So, we are getting married this month. [...] We had planned to put it off until the pandemic ends. But, what I realized was... things are going to remain the same and there is no point in delaying life events and activities because of this. (P19)

The participants from the lower-income groups, who remained out of work in the second phase, expressed “feeling left behind” (P30) and believed that lockdown was “not completely lifted” (P43, male, in his 20 s, low SES). They continued experiencing distress with physical symptoms for which they would self-medicate.

Most people from the labor class have gone to their hometowns. And the ones remaining here, like painters, carpenters... no one gives us work. We have to live this way. [...] We could not go to our villages. The trucks charge 4000-5000 rupees.4 For the past 60 days, I have been unwell. I developed a fever. Sometimes my whole body hurts. [...] I would take some paracetamol [medicine] and lie down. (P31, male, in his 40s, low SES)

Interviewees drew out positive inferences from unexpected negative consequences and changes in the second phase. P24, who had expressed job security in the previous phase, said,

The company has given me a final. I am getting laid off from work. I believe that it is good for me. The office is far away. Corona has gotten out of control. So, I will stay at home and stay safe. (P24)

Theme 2: Accountability and Lack of Trust

The participants attributed COVID-19, the lockdown, prejudice, and their effects to various factors. Lack of trust in the government, healthcare authorities, and news sources were expressed in both phases. Unable to employ problem solving coping, most people used avoidance or escape strategies. However, phase B witnessed a diffusion of responsibilities to the people for the spread of coronavirus. The participants emphasized greater self-compliance with COVID-related behaviors in phase B as they observed undesirable health behaviors in others.

Phase A: Ambiguous Communication and Xenophobia Leading to Lack of Trust in Institutions

A number of people held the government responsible for a lockdown “without strategy” (P14), and “no relief or aid” to the ones who were financially affected (P39). Fourteen participants from the low SES group reported receiving no or insufficient government aid. P31 said, “I feel suffocated. You never know when things will change. When laws will change. Laws are announced at night and are enforced in the morning.”

From the government5…once we received 493 rupees6 in my wife’s account and then 500 rupees.7 So, 900-9938 in the last two months. That’s everything we have. [...] I don’t have a ration card. The [village] pradhan [elected minister] said he would help me get one but the offices were closed. I was watching this yesterday…[TV] news showed that the government was sending rations to people without ration cards but I have not received any help. (P43)

While television (TV) news was one of the most popular sources of information among the participants, it also seemed to be the least trusted one. The participants said that TV was “very negative” (P03) and “did not show the full picture” (P01). Most participants expressed concern over “fake news on WhatsApp [a messaging application]” (P09, male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES). Interviewees said that they tend to rely more on digital and print media for authentic information and to “bust fake news” (P27).

While some participants expressed concern over particular groups spreading coronavirus, others were concerned about the attribution of the spread to particular groups. P05 said, “Ramadan is coming up and Muslims may gather and coronavirus may spread further… Of course, after all, it’s their festival. But I worry about it […] because I heard they spit everywhere during Ramadan because they can’t swallow the saliva.” P12 (male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES) said, “COVID-19 is an opportunity for people to express that racism [against Northeast Indians] as people have nothing else to do.” Social media was seen as a reflection of the xenophobic content broadcasted on TV. Taking a problem-solving approach by engaging with such content was overwhelming and distressing, and thus, people disengaged with social media platforms.

I would regularly see communal posts on a classmate’s Facebook which were painful to me and I started responding to it. [...] I was able to successfully resolve the discussion but I realized that the process of me seeing the post, going over it several times, dealing with the initial negative responses, and then finally coming to a resolution… it all took a toll on my mental health. So, I consciously decided to stay away from it [engaging on social media]. (P21)

The participants also expressed low trust in the healthcare system and authorities and avoided those. P16 said, “So many on-the-spot deaths have started and they are still increasing. So, then I feel that India’s healthcare system is not very good. So, if someone is infected, they have to take care of themselves.” P14 recounted his visit to the hospital when he developed a fever after coming in contact with a friend who had traveled from China in March 2020. The experience resulted in him avoiding encounters with healthcare and police.

I remember a girl screaming, “There is a corona patient here!” [...] Three-four doctors were there. One of them said, “He looks Chinese.” Actually, my mom has mongoloid features to an extent. My nose is like my dad’s. But my eyes are small. [...] So I was like I should take off from here. They called me an ambulance and asked me to go to [retracted hospital name]. But as soon as I stepped outside, I ran away from there. I was sure they were planning to kill me. (P14)

Phase B: Diffused Responsibility from the Government but Lack of Trust in Institutions due to Stigma

As the lockdown was lifted, the diffusion of accountability from government and authorities to personal responsibility was observed across many participants in the second phase.

Now cases will rise further because there is too much freedom. [...] It is up to us to protect ourselves. We are saying, “[the Indian Prime Minister] Modi is not doing anything, not delivering rations to us.” But what are we doing for him? We have to protect our country by taking precautions. (P11)

P24 said, “Now we have to protect ourselves. Earlier, the government was overseeing… but now we have to be safe, we should follow safety rules.” Many respondents perceived irresponsible behavior in others in the context of the pandemic. P14 said, “When there were 500 cases of corona, people had fear in their minds.[…] Today, the fear has disappeared.” Engaging in compliant behaviors and observing non-compliant in others created resentment and frustration.

Irritation and anger would be there [in me] because... See, I’m aware that I am taking care of myself, we’re taking precautions and we’re sanitizing our place every day. [...] So we’re doing our best to get... to save ourselves from this disease. But at the same time, I get angry when people just neglect all these seriousness [sic], [...] just because of their own selfish reasons, which are not necessary for survival, people are going out. (P18)

Many participants, mostly those from the low-income group, held the government responsible for lockdown-related difficulties. P31 said, “They imposed a lockdown when they should not have. And now that the cases are increasing, they have unlocked.” Others who criticized the unlock said that they “understand that it was required to restart the economy” (P12) but believed that “cases will further increase because of the unlock” (P07, male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high). P29 said, “[the government] should have given some time to people to go to their homes or safe places before announcing the lockdown… and then imposed a longer lockdown.” P04 (male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES) said, “The purpose of a lockdown is defeated. More people have died of hunger and suicide because they did not have money.”

Ambiguities related to lockdown impeded important financial decisions. P43, a daily wager and a farmer, avoided going back to the city for work, saying, “What if I go to the city for work and get stuck? The government announces its decisions overnight. So I am waiting for it to unlock further.” Lockdown-related rumors added to the distress. P31 said, “I heard that the lockdown will be re-imposed on the 15th [June 2020]. Our difficulties will further worsen.” Lack of trust in the government was expressed by participants; some believed that “[the government] is hiding the numbers [COVID-19 cases].” (P02). P12 described his experience at a quarantine center after traveling interstate to be with his family.

There was a lot of miscommunication. [...] They said, “it will take two-three hours to take the corona test and then you’ll be asked to home quarantine [sic].” [...] But once we reached there, the officials were like, “The DM has issued different instructions. You will have to stay here... get quarantined.” That gave me anxiety like crazy. [...] Luckily, the place we were quarantined in was a stadium [...] The main concern was... the stadium was clean but there was only one toilet to be shared. So that was... crazy. Because the results will come after three days. The fact that for the three days, you are using the same bathroom, same washbasin... with like 50-60 people. Imagine! (P12)

Participants, who could not approach mistrust in the governance directly, resorted to online activism.

The worst thing is I can’t go out and do anything about it. When you’re in a protest, you feel, “Fine, I am here doing something. There will be some impact.” But now I’m only reading things on social media... sharing links. (P45)

Lack of trust in the healthcare authorities was exacerbated by the experience of prejudice and mistreatment.

My cousin’s father-in-law went to the hospital and they asked him to quarantine. He did not have corona [sic]. He went for an operation. But they did not let him meet his sons, his family. The guys in the hospital were not treating him well. [...] After two days, we found out that he died. And then there was a blame game. Even my friend’s father, who was having a fever, went to the doctor. The doctor just asked him, “Are you from Tablighi Jamaat9?” because he had a beard and wore a skull cap. So, there is this constant fear of identity… as Muslims. (P26)

The participants also continued to attribute the xenophobic sentiment they were experiencing to TV news. P40 said, “I don’t watch TV anymore. Watching the news has driven people crazy. They think that Muslims are spreading the coronavirus.” In response to xenophobic content, others shifted their focus to different kinds of news.

I am selective in my approach to social media. I keep removing people on social media when I feel they are hazardous to my mind. The ones remaining… they have moved on to other topics from corona and they post about those. So I feel good. It has sort of given a relief [sic]. (P21)

Theme 3: Fear and Uncertainty

For almost all the participants, the unexpected lockdown prompted uncertainty about different aspects of their lives. The uncertainty resulted in fear, distress, and helplessness. Overall, uncertainty reduced in the second phase but low-SES participants continued to face financial insecurity. Fear related to stigma, police action, and healthcare anxiety continued to increase.

Phase A: Fear, Uncertainty, and Insecurity Hampered Daily Functioning

In phase A, the participants expressed fear related to COVID-19 infection, police action, and healthcare facilities. Some people reported a “feeling of impending doom” (P21, male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES) to describe uncertainty. Concern for the health of family members, particularly those who were elderly or had predisposing health conditions, led to increased COVID-related preventive behaviors. P04 said, “The only thing I fear about [sic] is that I have a family. I have a dadi10 who is sick. That’s why I am doing the social distancing thing at home.”

Besides wearing face masks, using sanitizers, and physical distancing, many reported being preoccupied with thoughts about the people and surfaces they came in contact with, as “they could be infected” (P37).

I experience anxiety related to cleaning everything. [...] When I wash vegetables or fruits, there is a little anxiety about whether I could properly clean them. What do I do with these? How do I test them? How do I sanitize perishable items? We bought mangoes and oranges; we washed them with soap and they all rotted in three days. (P6)

While many participants defined this perpetual set of thoughts as “paranoia” (P45), P19 perceived it as her being “more mindful.” Interviewees expressed anxiety about reporting symptoms or seeking treatment. P01 said, “I am anxious about going to hospitals… they are infected areas.”

Some participants hesitated going out for basic needs out of fear of police action. P25 said, “If I go out, the police will beat me up.” When people went outside, they felt a sense of urgency to rush back home. P14 said, “There is a shop right across the road. I run at full speed, I keep maximum distance, buy things quickly, and then run back inside my house. […] Now everything is focused on survival.” P38 said, “I am scared […] about riots. Communal riots. Because you know, there is a communal angle in the news about COVID.” Apprehensions related to judgment, stigma, rumor-mongering, and antipathy were also met with avoidance. P39, a migrant worker, said “There is no point in going back to the village as they [villagers] may be afraid that I am bringing the infection from Delhi.”

Personal, academic, and professional uncertainties were pronounced and intensified if there was a “lack of clear communication” (P08, male, in his 20 s, mid-to-high SES). Those who were unemployed as a result of the lockdown were unsure regarding work opportunities. P31 said, “We will have to work for lower wages after the lockdown is lifted,” further expressing uncertainty regarding accessing basic needs like food and housing. Fear of financial insecurity was also expressed by participants in the middle-to-high-income group.

My husband is a lawyer. Even if work starts… most of the clients he has come from small towns and villages. Their income sources have stopped; how would they hire a lawyer? So it would take a lot of time to cover up… about 4-5 months, 6 months to recover. Children’s studies are also taking a hit. (P01)

Being able to maintain hope helped participants facing financial insecurity to keep going.

Hoping that the lockdown would end by 17th [May 2020], as they [the Government officials] are saying, gives me the strength to continue. I am waiting [...] I hope to start working by May 18-19 [2020] and earn some money to feed my family. (P37)

The participants, who received external aid, worried about its shortage in the future and increased their consumption.

When I used to pay for my food, I would budget the rotis I eat so as not to spend more than 50 rupees11 [...] Now, if I ask for four rotis, they [neighbors] give me five. I have to eat it because food shortage is the biggest crisis right now. If I throw away even half a roti, I would feel, “I may have not even gotten this.” So, I force myself to eat it. My food intake has increased a lot this way. (P41, male, in his 30s, low SES)

Religious coping emerged at the face of uncertainty. P37 said, “Whatever God would do, would be for the best.” P44, a temple priest, redefined the pandemic in terms of religion, saying, “God has reincarnated in the form of the [Indian] Prime Minister […] Had he not imposed the lockdown, many people would have lost their lives.”

P12 applied learnings from his terminated therapy sessions by accepting uncertainty and the resulting emotions.

Sometimes I feel low… But I believe in—like—feeling it. If you feel sad, be sad. [...] My therapist told me this. [...] You can’t keep dreading each day because you never know when it [the lockdown] will extend. So, I have just accepted it in my head that it is okay if it extends. I’m mentally preparing for this for my own good. (P12)

Phase B: Risk Realization, Uncertainty, and Fear of Stigmatization Affected Planning and Decision-Making

Some participants believed that they were “less likely to get infected” (P21) as their “immune system [was] good enough to tackle” COVID or because they were “taking all the necessary precautions” (P07). However, as more cases emerged in their periphery or among acquaintances, P02 said, “COVID has become real now.” P15 said, “One of my college friends… he was tested [sic] positive, so I felt that… yeah, our age can also get it.” P16, who had earlier perceived low infection risk for himself, revealed that he tested positive for COVID but also reported a “positive [healthcare] experience because [he] was at an army hospital.”

Many respondents expressed anxiety about being around people as “anyone could be infected” (P03). P23 said, “Some say it [increasing COVID-19 cases] will get better, some say it won’t. We can’t be sure.” More people were concerned about the accessibility to healthcare if they were infected with the coronavirus. Some participants raised issues with the lack of facilities at hospitals requiring patients to “isolate at home” instead of admitting them (P35, female, in her 30 s, mid-to-high SES). P13 said, “We could get better medical facilities […] because we are on the well-off side of the population income curve.” P40 said, “Good healthcare services are for VIPs, not for the poor like myself.”

For one person in our household, we can manage. [...] If my grandmother becomes positive, then [the expense] is doubled. But, definitely, we are not going to send her to a government hospital because we know the condition of government hospitals. (P45)

The participants, thus, became aversive towards hospitals, especially government hospitals. P31 said, “The things I am hearing about hospitals. It’s better to die in your home.”

Several participants reported that, if tested COVID-positive, they would refrain from telling others for the fear of stigma and hate crime. P07 said, “Telling others will create more difficulty for you.” P14 elaborated, “If I told my family, they will get a heart attack out of worry. If I told the people in my society, they would lynch me. Other people would spread baseless rumors.”

Financial insecurities and uncertainty continued to prevail for most people in low-income groups; most of them reported inability to find paid work. P30 expressed uncertainty and helplessness about the inaccessibility to basic needs, saying, “[I wonder] what do I do? Will I have to end up begging for food?” The participants would avoid having direct conversations with their family and relatives about financial uncertainty.

I am always anxious. I assumed we would start earning a little bit after the lockdown ends. But we are unable to get work because of the corona. I keep thinking about what will happen to my children—I have four children. They ask me, “Papa, what are you thinking about?” I say, “Nothing.” But I am thinking about their future. (P32, male, in his 40s, low SES)

The unlock and increased mobility allowed hope. P43 stated, “Now that the unlocking is happening, there is some hope that maybe we will only struggle for one or two months… maybe six months. But after that, life would go back to normal.”

P10 (female, in her 40 s, low SES), a domestic worker, reported being “extremely stressed as [her] son’s school [had] closed” and they did not have access to online classes. P01 said, “Online classes […] are ineffective in comparison with normal [traditional] classes.” Furthermore, college students continued to express uncertainty about career opportunities. P15 added, “Even if I get a job, there are technical things, practical things that I am not able to learn in online classes. That I am not well-trained in. So, I won’t be able to perform.” People continued to accept, be “mentally prepared for,” and “embrace” such uncertainties (P12). For some, this acceptance was “out of compulsion” (P14).

Theme 4: Perceived Lack of Control

A majority of participants in phase A expressed a lack of control over their personal circumstances, psychological and physical responses, or the pandemic situation. Because lack of control was related to the most diverse number of stressors, it also covered the largest number of coping strategies. In phase B, the participants engaged in voluntary restraint to gain back control in addition to some freedom in mobility. Those who remained unemployed and financially distressed continued to express helplessness and distress.

Phase A: Perceived Lack of Control Leading to Lowered Distress Tolerance

Numerous people said that taking precautionary measures was out of their control to some extent.

Whenever our Prime Minister comes on the TV, the concept of social distance is thrown out of the window. He announces, “lockdown will extend by 30 days.” Now, what happens? People rush to the shops before his announcement is finished. They go to buy essentials and realize the grocery shops have 100 people in line already. Now, if 100 people maintain a distance of one-one meter, there will be a 100-meter line. We don’t have that [sic] big roads. (P14)

The participants often coped with the lack of control regarding lockdown rules by engaging in activities and hobbies for distraction. P16 said, “I try to listen to music or watch TV series. I keep my mind fresh and try to be positive […] because there is nothing much you could [sic] do when you can’t go outdoors.”

For the participants in the low-SES group, this lack of control was debilitating. P32, who was living with a physical disability, said, “Lockdown is imposed. I have no work, no income. I can only beg or borrow. Because nothing is in my capacity.” P22 used distraction in response to the lack of control regarding his financial situation, saying, “When I feel too stressed, I go to sleep.” P37 was “waiting” for the situation to pass on its own as he was “unprepared for the adversity” and was facing a shortage of essentials that led to frequent conflicts with his wife. Many others deferred control to a higher being, saying that “Everything is now in God’s control” (P22). Partial control allowed a more collaborative approach to religious coping. P25 said, “God will help me as long as I keep doing my part.” Social support and interaction helped against helplessness and mental exhaustion. P41 said, “My daughter [who had a speech impediment] has started saying “hello, hello.” Hearing that, I am filled with joy and relief that she has started to speak again. I feel full of life for some time.” Downward comparison was a way of coping with financial lack of control for participants in the low-SES group. P41 said, “I am able to use my savings to feed my children. So many other children are not even getting food.”

Making downward comparisons led to empathy-related stress and guilt in some mid-to-high SES participants. Coping with lack of control on humanitarian crisis by engaging in helping behavior alleviated guilt.

[We] were restless since the lockdown started. My friend said, “I can’t sit at home and let people die.” So we started [retracted name of a social initiative] to provide essentials to the underprivileged. [...] Somewhere I feel guilty for not doing enough. But then I think of the little things I do… I collect funds and send them. That makes me feel that, perhaps, there is someone who will not sleep hungry tonight… or there would be some positive change in someone’s life today because of our efforts. (P21)

Helplessness and guilt for their inability to help would lead participants to disengage with sources that informed them of humanitarian issues, however, that could induce more guilt of negligence.

Initially, I was following it [news sources] actively but it has affected me very much because every day I open the internet and there is one sad image of the migrant laborers or one sad image of people just walking or just dying out of hunger. [...] I saw this video from [retracted name] hospital where they are keeping the COVID patients with dead bodies wrapped in plastic bags and it just disturbed me so much that I was like, “I am not opening Instagram anymore” and I didn't. For a day I didn't. [...] I also feel bad that—because probably I am sheltered and I have food—that I am negligent which I shouldn't be… but then again it is affecting me so much just thinking that I can't go out and do something for these people. (P45)

“Seeing the number [of cases] increasing” (P19) and “overflow of information” (P13) from various sources left participants feeling overwhelmed, anxious, or sad.

Everywhere you are looking… at your home, even if a news channel is running in a different room, COVID-19 reaches your ears. When you call someone, it [the COVID-19 caller tune] plays, “clean your hands, wear face masks.” These things are all around you: corona. [...] Sometimes I do feel overwhelmed. So it is... a downpour of information. (P21)

The participants feeling overwhelmed reported that they had “stopped watching TV news” because it was “negative” and “depressing” (P05).

Due to lack of control, several participants expressed being “more frustrated” (P26) and “irritable” (P13), having more “mood swings” (P35), being “mentally exhausted” (P40, male, in his 40 s, low SES), and “physically exhausted” (P46), and overall, less tolerant of distress. P14 talked about how he could earlier manage issues more calmly, saying, “I get emotional outbursts. I know I cannot do anything about this. As in, I am packed in my room, closed off all the time, can’t meet anyone. There is a kind of anger. Rather, frustration.” Not confronting stressful thoughts was often used to cope when faced with helplessness. The participants tried to “avoid negative thinking” (P06, female, in her 30 s, mid-to-high SES). P11 said, “It’s of no use to think negatively because whatever has to happen will happen.”

Some participants positively framed the lack of control they experienced. P02 said, “I have failed to do things but I am guilt-free. Even if I go outside, nothing would happen because I cannot fix anything […] It’s liberating.” P19, a mental health professional, said, “Both [online and in-person sessions] have their pros and cons but now there is no choice. […] There is more control in face-to-face sessions but you can learn more about a person on video calls, seeing them at home.”

Phase B: Gaining Back Control or Facing Continued Helplessness

Unlike the lockdown that many considered to be “like a curfew” (P38), several participants in phase B indicated freedom of choice and mobility that came as “a relief” (P43). However, the participants from low-income groups who were unable to secure work after the unlock expressed increased helplessness in phase B. Problem-solving strategies such as trying to secure low-paying precarious jobs were employed at the cost of their physical and mental health.

I experience weakness… I have health problems. So, I can’t do labor work like my peers. But I guess that is my only option now—to do labor work—for some income. [...] My mother suffered a paralytic attack last year. Much of my savings go into her treatment. (P23)

While fewer participants indicated religious coping in phase B, continued lack of control led to the deference of control to God. P31, who was stranded away from home and in financial distress, said, “God is there. Whatever He plans for us, we have left it up to Him.”

For many participants, simply being around family seemed to be a supportive factor. P40, who was stranded in a city in phase A, retrospectively informed about suicidal thoughts.

All I could think about was taking loans, doing some work, and earning money somehow. [...] Sometimes, I would have extremely distressing thoughts, like, “I don’t have a job. How will I manage my family? What would I do?” And I thought about killing myself. [...] Now, I feel extremely happy [to be back home]. I am with my family. Now, no matter what happens to me, good or bad, I have no regrets because I am at my place. (P40)

P22 made downward comparisons, saying, “There are others who are suffering so much more than I am. So I am grateful, I thank God for my situation. […] when I see others, I forget about my struggles.”

P45 described her experience with Cyclone Amphan (see BBC News, 2020) which added to perceived loss of control. Making downward comparisons induced further guilt.

For around four weeks, we had no Wi-Fi [...] WhatsApp messages were taking four to five days to deliver. Everything was in [sic] a standstill. So it has been quite a bouncy ride, if you ask me, I have had extreme mood swings [...] Because, even in the lockdown, all we get to do is be on our phones or on our laptops. And when you don’t have Wi-Fi, that gets restricted. And for the first few days, most of the people did not even have electricity, and I was very fortunate that I did. So I don’t know how terrible it is for most of the people [...] The accessibility was also reduced because of the lockdown, so it was a burden on top of this pandemic.

Continued helping behavior aided in countering empathy-related stress.

Had [redacted social initiative name] not been there... Firstly, I would not have gotten a chance to go out, help people, and report to those people who had contributed their money. Had these three things not happened, I would not have felt a sense of satisfaction. (P21)

Others drew positive inferences to reduce empathy-related distress. P03, who expressed worry about the less privileged in the previous phase, said, “I am relieved now. I was relieved after I learned that the government was helping the poor… My housekeeper was transferred 500 rupees12 to her account during the lockdown. So, I realized that everyone is receiving help.”

Although the participants reported reduced circulation of COVID or lockdown-related information, many others still felt “anxious” as they felt “bombarded with the news” (P38). The participants adopted a “social media detox” (P45) to maintain their “digital well-being” (P15). P42, who talked about reducing news consumption in the previous phase, said, “Now it’s even lesser [sic]. I realized that I should not read the news which triggers my anxiety.”

P02 compared his own experience to the previous phase, saying, “lack of control was there the last time and is still there. Earlier it was liberating, but now it… it is making me restless, making me unsure, anxious.” P14 said, “The most trivial things trigger me and I get angry. […] Living alone is the main problem.” P21, whose mode of teaching had become completely online, said, “When there are technical issues and I have to work… I get angry and feel like smashing my laptop into the ground.”

Respondents attempted to gain back control through COVID-related behaviors to improve distress tolerance. Despite the relaxation of quarantine rules, participants asserted that they were voluntarily restraining themselves by not going out or avoiding social gatherings “from a safety point of view” (P03). P23, who lived with a family of 40–45 people, added, “None of us go out. Only the office-goers. Even when I go out, I keep a distance from everyone. Secondly, I tell others to keep their distance. If they don’t listen, I distance myself.” P11 said, “There is no need to go out. Most things are available at the doorstep.” While the parent sample raised concerns regarding online classes, they were not keen on sending children to schools “because it is very unsafe for children” (P01).

Discussion

The present study addresses the need for a longitudinal qualitative inquiry into the experiences of a relatively large and diverse sample during the COVID-19 lockdown and unlock in India. It provides a deeper, more nuanced insight through the voices of participants from various income groups, occupations, and to some extent, religious backgrounds, and sexual and gender groups. The emerging themes and factors in the study overlap with each other as they are reciprocally related.

Our results support previous work on mental health outcomes of COVID-19 and its consequences (Ferguson et al., 2021; Khoury et al., 2021). Phase A presented the immediate effects of involuntary quarantine, such as changes and stagnation in various spheres of life, including changes in routine, physical activity, and professional, personal, and financial aspects (Ferguson et al., 2021). While some participants had the option to work from home, other participants (or the earning members of their families) were laid off from work. In phase B, participants faced readjustment challenges as they had to go back to their pre-lockdown routines without the pre-lockdown situation—a “new normal,” which involved adapting, accepting, or normalizing observed changes. Securing employment, however, was supportive for participants who expressed job insecurity in the previous phase. Almost all the participants from the lower SES groups were unable to secure a livelihood, facing long-term psychological distress and bodily responses. Depending on their appraisal of situations, thoughts, and available resources, the participants employed, continued, or abandoned various coping behaviors and strategies. These factors also determined whether the participants could transition smoothly into the “new normal” presented in the unlock or faced adjustment challenges.

At the primary level of appraisal (see Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), the majority of the participants appraised the COVID-19 lockdown and its consequence as stressful and the flow of information around it as overwhelming. It was perceived as harmful to financial security, physical and psychological well-being, and non-familial relationships. Being unprepared for the changes and sudden lack of access to daily needs and interaction opportunities triggered uncertainty and lack of control.

The participants from the low-SES group believed that they did not have the appropriate resources to deal with stressors effectively, as all of them had lost their jobs during the lockdown. Many of them were migrant workers stranded away from their hometowns with a lack of access to basic needs and transport (Jha & Kumar, 2020; Srivastava et al., 2021). They experienced more lack of control, uncertainty, and hopelessness. They viewed the lockdown as a long-term threat to their financial stability and existence. Religious minorities (Muslims), stranded migrant workers, and those experiencing empathy-related stress viewed the situation as a social threat—social exclusion, damage to reputation, or violence (see Saalfeld et al., 2018; Ahuja & Banerjee, 2021; Srivastava et al., 2021). Students and parents of students viewed the events as a threat to academic development and future career prospects. Unlock was largely viewed as a threat to health and healthcare. Individuals with a history of anxiety or depression were not more vulnerable to the symptoms during the lockdown than individuals with no history of those conditions (c.f. Sharma & Subramanyam, 2020). A possible explanation could be that those who reported a history of diagnosed psychological conditions also mentioned taking therapy, which equipped them with psychological resources to manage negative emotional outcomes.

Stressors associated with disruption, loss, and threat compounded the distress caused by the lockdown, resulting in poor well-being (Ferguson et al., 2021). This manifested in the form of physical and emotional responses: frustration, low mood, mood swings, poor sleep quality, anxiety, headaches, lack of motivation, loneliness, and lethargy (see Brooks et al., 2020; Chakraborty & Chatterjee, 2020; Kwong et al., 2021; Yan & Huang, 2020). A longitudinal study by Rehman and colleagues (2022) found that symptoms of depression and anxiety were reduced with lower restrictions. In our study, this result was contingent upon financial and social resources available for adjustment and coping. Suicidal ideation was reported by one study participant in retrospect; previous literature (e.g., Barbisch et al., 2015; Gruber et al., 2021; Yip et al., 2010) suggests that long durations of confinement and lack of access to coping resources could lead to extreme behaviors, such as suicide. Adding to that, hopelessness and helplessness, expressed frequently in this study by the low-income group, play a role in suicidal ideation, intent, and behavior (see Johnson & Tomren, 1999; Weishaar & Beck, 1992).

Ambiguous communication and sudden policy changes from the state added to the distress, causing a lack of trust in institutions and uncertainty. With a lack of awareness and overflow of information, it became difficult to pick apart facts from rumors, thus it became easier for false information and xenophobic content to be largely circulated, especially in phase A. Uncertainties, along with financial distress and hindered accessibility, triggered a scarcity mindset that hampered planning, self-control, and decision-making (Heshmat, 2015; Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013). While people questioned policy decisions in phase B, the accountability of the pandemic outcomes was diffused to the Indian citizens. Observing irresponsible behavior in others while reporting voluntary restraining behaviors by oneself produced feelings of resentment. This difference in observation supported the findings of Williams et al. (2020). However, it was more prevalent in our study in phase B rather than during the state-mandated quarantine. This may suggest that voluntary quarantine leads to greater compliance than a mandatory one (Rubin & Wessely, 2020) . Or, this could have been observed due to the order of events; by the time of the unlock, people became more aware of undesirable COVID behaviors they observed in others while ignoring or justifying their own.

The reported lack of trust was raised between the two phases. Many participants believed that the Indian healthcare system was too overwhelmed or incompetent to provide proper services to them. For the participants from minority/marginalized groups (religious minorities, sexual/gender minorities, Northeast Indians), the lack of trust was based on the fear or experience of stigma, prejudice, and antipathy faced in healthcare institutions (see Ahuja & Banerjee, 2021; Pellecchia et al., 2015). The participants from the low-SES group added that they could not afford “good” private hospitals and did not trust (like other participants) subsidized government hospitals owing to their poor conditions. One participant, a trans woman, indicated inadequate access to gender-sensitive healthcare aggravated during the pandemic (Pandya & Redcay, 2021) .

While the fear of infection led to some compliant behaviors, fear of police action hampered daily functioning, such as going out for basic needs or earning a livelihood. Minority and low-SES groups, in particular, reported more fear of police violence. In general, lack of trust and fear led some participants to avoid encounters with healthcare or law enforcement. Many would make consequential health-related decisions, such as not reporting or not intending to report COVID-related symptoms (see also Blair et al., 2017). Lack of control, anxiety, and lack of trust in the government and healthcare could also lead to conspiracy beliefs and vaccine hesitancy (Ahorsu et al., 2022; Šrol et al., 2022).

Not being able to go out was a common source of lost control along with the lack of regulation over information. Perceiving a lack of control over the situation lowered participants’ distress tolerance. While fewer people reported emotional outbursts in phase B as restrictions relaxed, continued lack of control exaggerated distress intolerance along with heightened feelings of helplessness and hopelessness and interpersonal conflicts. More often than not, these participants were from low SES groups and those who lived alone (Marmet et al., 2021; Raina et al., 2021). Some participants reported empathy-related stress or stress about the well-being of others (Ferguson et al., 2021); they expressed guilt and anxiety if they were unable to help others directly (Feng et al., 2020).

Similar to previous findings (see Ferguson et al., 2021; Grover et al., 2020), positive appraisals were indicated in phase A, perceiving lockdown as an opportunity for relaxation, personal growth, and family bonding. However, these were almost exclusively the experiences of participants from the mid-to-high SES group (Williams et al., 2020). On the other hand, for the participants from sexual/gender minorities and those with a history of abuse at home, being stuck with family was anxiety-provoking and viewed as a psychological threat (Fish et al., 2020); see Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Sharma & Subramanyam, 2020). Non-familial interactions (with peers, potential romantic partners) decreased, and virtual modes were considered ineffective in building deeper relationships, which may have further added to loneliness and anxiety (Sharma & Subramanyam, 2020). Work-from-home setup received mixed attitudes as people appreciated the autonomy it provided (Schade et al., 2021), while others experienced a lack of choices because of their profession (such as mental health professionals).

The families of coping (see Table 2) remained stable throughout the study, but the manifestation of coping strategies changed depending on the stressors and major participant characteristics. Distracting activities like consuming entertaining content to cope were popularly used to deal with isolation, monotony, and lack of control during the lockdown (Sameer et al., 2020; Sweeny et al., 2020). These activities were either replaced by other elements in the routine in phase B or were difficult to sustain (such as meditation). Having schedules or plans was an effective way to cope with the unstructured time (Van Hoye & Lootens, 2013) and was continued in phase B. Acceptance of one’s situation and uncertainty and the lack of control allowed the stress these caused to be minimized (Shapiro et al., 2011).

Although escape/avoidance is considered a maladaptive coping strategy (e.g., Allen & Leary, 2010), it was effective in coping with an overflow of information surrounding the pandemic (see Yoon et al., 2021) and perceived xenophobia (which was also attributed to TV news and mass-sharing applications). The participants blocked or muted certain channels or avoided certain social media entirely. The participants from the low-SES group who experienced prolonged helplessness passively coped by waiting or letting the situation pass on its own, as even after the unlock many facilities and opportunities remained unavailable to them.

The participants used positive cognitive restructuring by actively reframing their situations positively, pursuing hope, or making downward social comparisons to cope with distress (Allen & Leary, 2010). Downward comparisons (comparing one’s situation to those who were perceivably having poorer experiences of the lockdown; see Festinger, 1954) were made regardless of their socio-economic status; low SES groups, too, acknowledged relative privileges, such as better access to food or social support than many others (Srivastava et al., 2021). Perhaps to avoid empathy-related stress from the inability to help (Feng et al., 2020), some participants in phase B expressed the belief that the vulnerable groups they were worrying about received some relief or rehabilitation.

Many participants chose to directly confront the problems after the lockdown (problem-solving). Some dealt with empathy-related stress through prosocial behavior, which reduces anxiety and guilt, and is a source of meaning (Van Tongeren & Showalter Van Tongeren, 2021). Low-SES participants engaged in helping behavior despite their own distress, perhaps, due to the additional reason of affinity (Bennett, 2011). To deal with the lack of control in helping directly, interviewees took to social media activism. Some participants self-medicated for health conditions, including symptoms of SARS-CoV-2, to avoid hospitals, perhaps due to the fear of stigmatization (Sadio et al., 2021). Acceptance of a long-term pandemic and a “new normal” also led participants to take a problem-solving approach by taking back control of delayed life events.