Abstract

The study sought to ascertain the changes in the food insecurity status of households during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study made use of secondary data obtained from the 5 Waves of the National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM). Descriptive statistics, food insecurity index and independent sample t-test were used to compare the mean differences in the food insecurity statuses of the households over the 5 Waves. The study found that there was an increase in food insecurity as the COVID-19 progressed from Wave 1 to 5. Significant differences at the 1% level were observed between Wave 5 and Wave 1 as well as between Wave 5 and Wave 3. The study concludes that there was food security in the initial progression of the COVID-19 pandemic which deteriorated. The study recommends a reconsideration of the scrapping of the top ups on the social grants. This will likely tighten the dire economic situation the households find themselves in. There is need to expand the social safety nets to accommodate the vulnerable in society. Short and localised value chains should be promoted to improve food accessibility during times of crisis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Food insecurity index, Independent t-test, NIDS-CRAM, South Africa

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was instrumental in increasing food insecurity and hunger especially in the Global South (Crush and Si, 2020). According to Crush and Si (2020) the COVID-19 pandemic likely doubled the number of severely food insecure people from 130 million to 265 million by the end of 2020. The increase in food insecurity was more pronounced in urban areas due to disruption to food systems and supply chains from control measures. Crush and Si (2020) identify that even though “essential services” through formal food systems like supermarkets and formal retailers remained operational and were less affected, non-formal systems were affected through shutdowns through restrictions on internal and external movement. Besides the disruptions in food supply systems, this resulted in ban of informal food markets, job losses, income declines and compromise of school feeding programs, which increased food insecurity (Crush and Si, 2020). Illness and death of food systems’ workers, currency depreciation and social safety net disruptions were also instigated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Mohamed et al., 2021). Response related actions to the COVID-19 pandemic undermined food production, processing and marketing and thus physical access to food (Devereux et al., 2020). This raised food insecurity policy concerns, especially in countries such as South Africa (Patrick et al., 2021).

In South Africa, there is food security at the national level, but food insecurity at the household level (Oluwatayo, 2019; Raidimi and Kabiti, 2019). High levels of poverty and inequality have necessitated this. According to de Klerk et al. (2004) by 2004, 14 million South Africans suffered from food insecurity, 43% of households suffered from food poverty and 1.5 million children had malnutrition. By the year 2015, Walsh et al. (2015) highlighted that 26% of households in South Africa were food insecure, whilst 28.3% were at risk of being food insecure. In a more recent report by IPC (2021), it was indicated that 8.18 million people in South Africa were in crisis and 1.16 million were in a state of emergency in terms of food insecurity in December 2020, with projections to increase to 9.60 million and 2.20 million by March 2021, respectively. The main drivers of this increase in food insecurity included economic decline and unemployment, food prices, drought and the COVID-19 pandemic (IPC, 2021).

The first COVID-19 case in South Africa was reported on 3 March 2020 (NICD, 2020). This led to the South African government declaring a State of National Disaster on 15 March 2020, after 51 cases and zero deaths (GoSA, 2020a, 2020b; van Walbeek et al., 2020), and a subsequent 35 day lockdown. The interventions included the closure of business during lockdown except for essential services in what was later called Alert Stage 5 from 26 March to 16 April 2020, and then extended up to 30 April 2020 (GoSA, 2020c; van Walbeek et al., 2020). Fernandes (2020), estimated that the South Africa's economy would shrink by 3.2% due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Continuation of the lockdown up to mid-June 2020 would result in the economy shrinkage of 6.8%, with a 10.8% shrinkage when it continued up to July 2020 (Fernandes, 2020). The South African government proposed a R500 billion bailout, 80% of which was going to be sourced from various international lenders (Steyn and Klopper, 2020). This fiscal support combined revenue and spending measures, with loan guarantees, at 10% of South Africa's GDP (Department of National Treasury, 2020). The breakdown of the R500 billion fiscal response is shown in Table 1 , with the various sources of such funding in Table 2 . As of 26 December 2021, South Africa had 3 407 937 cases, with 90 773 deaths (DoH, 2020; Worldometer, 2021).

Table 1.

COVID-19 bailout package in South Africa.

| R million | |

|---|---|

| Credit guarantee scheme | 200 000 |

| Job creation and support for SME and informal business | 100 000 |

| Measures for income support (Further tax deferrals, SDL holiday and ETI extension | 70 000 |

| Support to vulnerable households for 6 months | 50 000 |

| Wage protection (Unemployment Insurance Fund) | 40 000 |

| Health and other frontline services | 20 000 |

| Support to municipalities | 20 000 |

| Total | 500 000 |

Table 2.

Sources of funding the COVID-19 bailout package in South Africa.

| R million | |

|---|---|

| Credit guarantee scheme | 200 000 |

| Baseline reprioritisation | 130 000 |

| Borrowings from multilateral finance institutions and development banks (IMF, World Bank and New Development Bank) for business support | 95 000 |

| Additional transfers and subsidies from the social security funds | 60 000 |

| Available funds in the Department of Social Development (2020)/21 appropriation | 15 000 |

| Total | 500 000 |

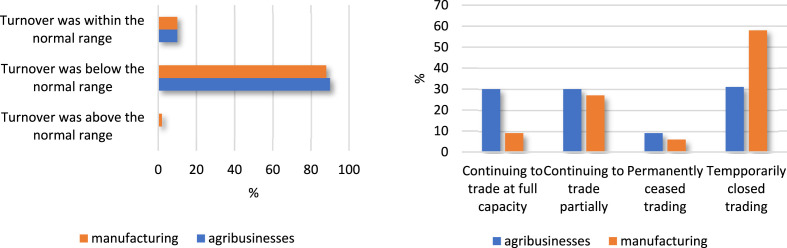

Fig. 1 shows that from a sectorial view, 90% of the businesses in the agro-industries in South Africa indicated that turnover was below normal, slightly more than manufacturing, during the lockdown periods. Furthermore, 9% of agro-businesses permanently ceased trading, with 5% of the businesses in the manufacturing sector ceasing trading during the lockdown (Govinden et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

Turnover and continuity of agri-business as well as manufacturing businesses due to COVID-19

Source:Govinden et al. (2020).

For South Africa, as a result of COVID-19, 19% percent of businesses had increased prices of materials, goods and services, with 30.6% being able to survive less than a month without turnover, whilst 54% could survive for 1–3 months without turnover. Furthermore, 34.6% and 40.5% of the businesses indicated that the exports and imports of goods and services was affected, respectively (Govinden et al., 2020). In the SME sector, 49% of the businesses had between 70% and 100% lower monthly turnover (PKF South Africa, 2020).

The South African government's economic response proposed additional tax measures (Department of National Treasury, 2020). These included the COVID-19 Temporary Employer/Employee Relief Scheme, the Tourism Relief Fund and other support to small businesses and employees. A four-month skills development levy holiday was enacted from 1 May 2020. Value-added-tax (VAT) refunds were expedited. There were 90-day payment deferrals for excise taxes on tobacco and alcoholic beverage products due to their restrictions. Filing and first payment of carbon tax was deferred by 3 months from 31 July to 31 October 2020 (Department of National Treasury, 2020). The proposal to broaden the corporate income tax base was shelved from 1 January 2021 to 1 January 2022. The wage subsidy of each employee who earned less than R6 500 per month was increased from R500 to R750 per month. There was a 35% employee liability tax deferral for a four-month period ending 31 July 2020. A portion of corporate income tax payments were also to be deferred over the six months ending 30 September 2020. The gross income threshold was increased from R50 million to R100 million. Businesses were also allowed to apply for tax deferment at SARS without incurring penalties. During the 2020/21 tax year, the tax-deductible limit for donations increased from 10 to 20% of taxable income. The pay-as-you-earn was adjusted for donations made by the employer to the Solidarity Fund (when donations were up to 5% of the employees' monthly salary). The access to living annuity funds was expanded by increasing from 17.5% to 20% or decreasing from 2.5% to 0.5% the proportion received as annuity income (Department of National Treasury, 2020).

A plethora of studies in South Africa have been conducted to ascertain the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic mitigatory measures on income and food security. According to Groot and Lemanski (2020) the early stages of the lockdown measures in South Africa severely affected food security through prohibition of vending and informal food systems. This affected the urban poor who have limited access to formal markets (Groot and Lemanski, 2020). Arndt et al. (2020) utilised the Social Accounting Matrix in determining income/expenditure flow for all economic agents. The study found that households with low education labour and high dependence of labour income were strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. This in turn had negative implications on the food security status in these households. Patrick et al. (2021) conducted a desktop review of food security in the COVID-19 era in South Africa. The study had limitations in terms of inferences as to the food security status during the pandemic. Odunitan-wayas et al. (2021) conducted a study that focussed on the food security status of urban immigrants in South Africa. The study found that the food insecurity of immigrants was compounded by social injustice and income inequality. The study was however not empirical. Tsakok (2020) also utilised a non-empirical method in assessing food security in a context of COVID-19 in South Africa. This was also the limitation to a study by Pillay and Scheepers (2020) who assessed the response of the South African transport department to food security during the COVID-19 pandemic. Wegerif (2020) also utilised non-inferential techniques in ascertaining the experiences of informal food traders on food security during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. These studies have limitations of being non-inferential and therefore not backed by empirical data and findings. van der Berg et al. (2021a) utilised the National Income Dynamics Study – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile (NIDS-CRAM) survey Wave 5 data and found that there was high food insecurity in the first Wave which declined in Wave 5 in South Africa. Their study and conclusion however were based on descriptive statics which was not inferential. According to Amare et al. (2021) the COVID-19 pandemic affected household food security through reducing income-generating activities, locally and from remittances. Furthermore, the heightened restrictions disrupted the livelihood activities, food systems and value chains. This increased food prices, limiting affordability and availability (Amare et al., 2021). However, there has been few studies that have empirically analysed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security, especially from household data in South Africa (Folayan et al., 2021). The country has exhibited food insecurity at the household level. Furthermore, the COVID-19 ravaged the country, instigating the country to lockdown conditions, which further worsened the household food insecurity status. The objective of the study was to ascertain the changes in the food insecurity status of households during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Literature review

Various studies have been undertaken that assess the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on food security. In global study reviews, Laborde et al. (2021), Béné et al. (2021) and Workie et al. (2020) indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic affected food security through income, demand and food supply shocks as well as hoarding, food waste and dietary shifts both at consumer and country level. This affected food accessibility especially through financial and physical access. However, availability was not affected. In addition, food supply and food demand were affected by the pandemic by affecting the purchasing power and ability to produce and the logistics thereof. These tend to indicate the dynamics in food stock and prices (Béné et al., 2021; Laborde et al., 2021; Workie et al. (2020)). In Bangladesh, Rahman et al. (2022) and Ruszczyk et al. (2021) found that income fell and there was limited access to livelihood opportunities during the COVID-19 pandemic, affecting food systems. This had a knock-on effect on the quantity and quality of food consumed. In telephonic surveys in Guatemala and India respectively, Ceballos et al. (2021) and Jaacks et al. (2021) indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic affected farmers ability to sell their produce, decreasing daily wage and dietary diversity. This was compounded by increasing fruit and vegetable consumption and decreasing animal source food consumption. However, Pakravan-Charvadeh et al. (2021) showed that in Iran, food security improved during the pandemic, with households reducing consumption of some food groups. Food security was affected by personal savings, nutrition knowledge, household head employment status and household income, while dietary diversity was affected by the number of male children, personal savings, occupation of household head and household size. Shupler et al. (2021) and Elsahoryi et al. (2020) showed that in Kenya and Jordan, respectively, the COVID-19 pandemic had tangible impacts on food security with 95% decrease in incomes leading to 88% of households reporting food insecurity.

Noticeable shortcoming in the literature have pertained to the methodologies that have been used, which have been mainly non-empirical reviews (Béné et al., 2021; Laborde et al., 2021; Workie et al. (2020)). This could have been due to the nature of the COVID-19 lockdown themselves which restricted movement and thus the inability to collect quantifiable and empirical data. Other authors such as Pakravan-Charvadeh et al. (2021), Elsahoryi et al. (2020) and Inegbedion (2021) circumvented this by using cross-sectional surveys but there was no clarity as to how impact of the pandemic on food security was measured. Shupler et al. (2021) utilised a longitudinal study to assess impact of the pandemic on food security before and after the lockdown in Kenya. The shortfall was that the study did not measure intermittent changes of food security in the progression of the pandemic. The study focussed on two ends, pre and post COVID-19 and did not measure the intermittent food security status as the pandemic progressed. This was also a limitation to the study by Amare et al. (2021) in Nigeria, which developed a food insecurity index and assessed the differences in food security pre and post COVID-19. In ascertaining the changes in the food security status of households during the COVID-19 pandemic, the current study utilised intermittent food insecurity index measures which showed changes as the pandemic progressed.

3. Materials and methods

The study made use of secondary data obtained from the 5 Waves of the National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey, 2020a, National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey, 2020b, National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey, 2020c, National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey, 2021a, National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey, 2021b. The NIDS-CRAM surveys assessed the socioeconomic impacts of the lockdown instigated by South Africa from March 2020 after declaration of National Disaster brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic (Ingle et al., 2021). The NIDS-CRAM surveys utilised Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) which were repeated over several months (Ingle et al., 2021). In order to obtain a nationally representative sample, the participants in the NIDS-CRAM were obtained from the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS), which was undertaken by the African Labour Development Research Unit in 2017. Data in these surveys was collected in the native language of that specific area within South Africa at various dates. Wave 1 data was collected between May–June 2020; Wave 2 between July–August 2020; Wave 3 between November–December 2020; Wave 4 between February–March 2021; and Wave 5 between April–May 2021. Wave 1 had a total of 7073 respondents that were successfully interviewed. An additional 1084 randomly selected sample was added in Wave 3 due to attrition between Wave 1 and Wave 2 (Ingle et al., 2021). At the end of Wave 5, 5862 respondents had been successfully interviewed since Wave 3, in a longitudinal manner.

3.1. Sample size and location

In the current study, after data cleaning, the total number of respondents were 5775 with the distribution outlined in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Sample size.

| Province | Eastern Cape | Free State | Gauteng | KwaZulu-Natal | Limpopo | Mpumalanga | North West | Northern Cape | Western Cape | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 588 | 348 | 884 | 1669 | 613 | 547 | 351 | 343 | 432 | 5775 |

| % | 10.2 | 6.0 | 15.3 | 28.9 | 10.6 | 9.5 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 7.5 | 100.0 |

The questionnaire template that was used during the telephonic interview in the NIDS-CRAM survey consisted of various sections that focussed on the demographic and socioeconomic status, labour and income, household and social outcomes, as well as health and COVID-19. The questionnaire adhered to ethical principles with approval from the University of Cape Town (REC, 20202/02/017) and University of Stellenbosch (REC 15433).

3.2. Analytical framework

The study utilised descriptive statistics, food insecurity index and independent sample t-test to compare the mean differences in the food insecurity statuses of the households over the 5 Waves.

-

i.

Food insecurity index

The food insecurity status was obtained through a food insecurity index based on the 3 questions (herein after referred to as indicators) in that data set that focussed on households that ran out of money to buy food; anyone in the house that had gone without a meal in 7 days; and any children in the household that had gone hungry due to lack of food. The Min-Max normalisation method as used by Ngarava et al. (2022, 2020) was used to produce an indicator which fell between a range of 0–1, using the following metrics:

where , and are the observed, minimum and maximum values of the indicator, respectively. The indicators were combined using equal weighting once standardisation was established. The 3 indicators were averaged using the formula below:

where and are the food insecurity index and the number of indicators respectively. The is scaled from 0 (food secure) to 1 (food insecure). The indicators that were utilised to compute the food insecurity index are shown in Table 4 .

-

ii.

T-test for differences in food insecurity indices over the 5 Waves

Table 4.

Measurement of indicators used in the formulation of the food insecurity index.

| Indicator | Measurement | Wave | Mean | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household ran out of money to buy food | Binary (0-Yes, 1-No) | 1 | 0.483 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0.595 | ||||

| 3 | 0.546 | ||||

| 4 | 0.580 | ||||

| 5 | 0.604 | ||||

| Anyone in the house that had gone without a meal in 7 days | Binary (0-Yes, 1-No) | 1 | 0.736 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0.809 | ||||

| 3 | 0.781 | ||||

| 4 | 0.808 | ||||

| 5 | 0.810 | ||||

| Any children in the household that had gone hungry due to lack of food | Binary (0-Yes, 1-No) | 1 | 0.810 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0.863 | ||||

| 3 | 0.812 | ||||

| 4 | 0.843 | ||||

| 5 | 0.845 |

The mean differences between the food insecurity indices over the 5 Waves were compared using an independent t-test. The independent t-test was specified as follows:

where and represent the Waves to be compared. In this instance, Wave 5 was used as the base wave from where other waves were compared. and were the means of the two waves that were compared, whether Wave 5 vs Wave 4; Wave 5 vs Wave 3; Wave 5 vs Wave 2; or Wave 5 vs Wave 1. represents the common variance of the two samples that were compared. It was calculated as follows:

The degrees of freedom used in the test were calculated as follows:

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

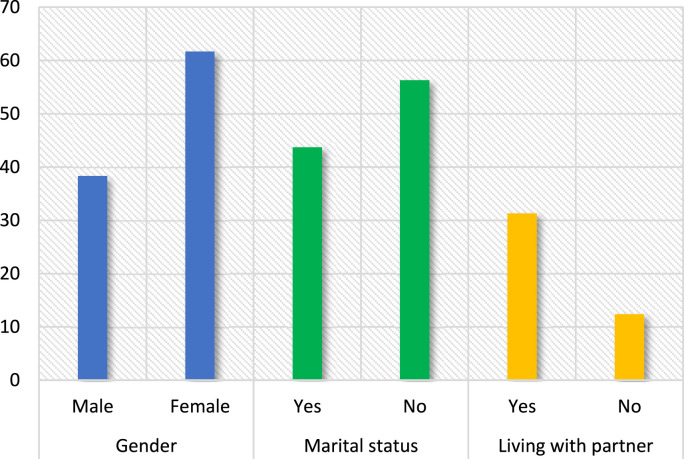

Fig. 2 shows that there were 61.7% female respondents relative to 38.3% male. According to van der Berg et al. (2021a) female respondents reported more food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is due to female headed households being poorer and having a large number of dependents. In addition, females have lower decision-making capabilities in terms of resources (van der Berg et al., 2021a). Casale and Shepherd (2021) add on highlighting that in South Africa, the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns resulted in women suffering a large and disproportionate effect in the labour market. This was further affected by the overburden of child care that was brought about by the lockdowns. Fig. 1 further shows that 56.3% of the respondents were not married compared to 43.7%. Out of the total that were married, 31.3% were living with their partners, whereas 12.4% were not. Kleve et al. (2021) found that marital status was significant in the food security status of households. Furthermore, it was women who are in these marriages/partnered households that experience food insecurity (Kleve et al., 2021).

Fig. 2.

Gender, marital status and living condition of respondents.

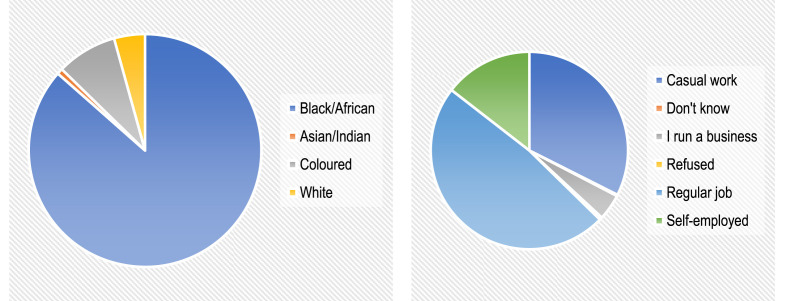

The majority of the respondents were Black/African (86.5%), followed by Coloureds (8.4%), White (4.3%) and Asian/Indian (0.8%) (Fig. 3 ). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased inequalities of race (Cooper and Kramers-olen, 2021). This inequality can be exacerbated by racially based inequalities in social partners, organised labour and within business (Francis et al., 2020). According to Nwosu and Oyenubi (2021) race contributes to income-related inequalities in poor health during COVID-19, with Black/African bearing the largest brunt. This is reinforced by Black/Africans being highly exposed to the pandemic through hazardous employment (e.g. nurses and fumigation of contaminated areas) and in-access to quality health (Nwosu and Oyenubi, 2021). In addition, Fig. 3 shows that 48.2% of the respondents held regular jobs, whilst 32.4%, 14.5% and 4.3% had casual work, were self-employed and ran a business, respectively. A study by Amare et al. (2021) indicated that there was high resilience to the COVID-19 lockdowns in Nigeria for wage-related activities and farming activities. Furthermore, food insecurity was heighted for households that relied on non-farm businesses, poorer households and those living in the fringes. The COVID-19 induced lockdowns resulted in increased unemployment which has a multiplier effect on production and demand, spilling over into the macro-economy (Arndt et al., 2020).

Fig. 3.

Population group and type of employment of respondents.

Forty-five percent of the respondents resided in urban areas/towns whereas 42.3%, 12.1% and 1.1% resided in farm/rural, traditional areas/chiefdom or where unclear, respectively (Fig. 4 ). According to Odunitan-wayas et al. (2021) food insecurity in South Africa mostly impacts the urban poor due to COVID-19 induced lockdown having a bearing on their livelihoods. Urban areas also exhibit high levels of inequalities. Social, physical and economic access to food is also compromised in urban areas which rely on centralised markets which were affected by the lockdowns. This was less pronounced in rural areas. However, reduced mobility during the lockdown reduced remittances into the rural areas also compromising food security (Moseley and Battersby, 2020). Fig. 4 also shows that the main source of household income was formal employment (43.9%), followed by government grants (41.3%), own business (5.9%), gifts from friends and family (3.7%), pension (2.5%) and lack of income (2.2%). This had direct impact on their food security (Picchioni et al., 2021). Baldwin-ragaven (2020) however averred of an increase in reliance on social grants by households in South Africa, relative to paid employment. A study by Kleve et al. (2021) in Australia showed that changes in employment status induced by COVID-19 lead to an increase in food insecurity.

Fig. 4.

Type of residential area and main source of income of respondents.

Child support grant was the main government grant that was received by the households during the COVID-19 pandemic at 39.4% of the households, followed the R350 COVID-19 social relief of distress grant (29.7%) and old age pension grant (22.7%), respectively (Fig. 5 ). The least was from care dependency grant and grant in aid at 0.3% each. van der Berg et al. (2021a) indicates that the expansion of the child support grant has enabled households to increase food security for children. A study by van der Berg et al. (2021a) found an increase in child support grant and social relief of stress grant targeting households that were more vulnerable to running out of money and reporting child hunger. Fig. 5 also shows that for respondents that were formally employed, 32.9% were from community, social and personal services, 14.1% from wholesale and retail trade, repair, hotels and restaurants, 9.0% from financial intermediation, insurance, real estate and business services, respectively. The least were self-employed at 0.3%. In Kenya and Uganda, Kansiime et al. (2021) found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was less severe food insecurity effects for those who were self-employed in the agricultural sector, especially farmers, relative to household who had their food needs reliant upon markets. Picchioni et al. (2021) augment, indicating that there was resilience from shorter value chains and traditional smallholder agriculture, especially in terms of food security through accessibility, availability and diversity.

Fig. 5.

Main types of grants and employment sector of households.

4.2. Food insecurity status of households in the 5 waves under COVID-19 conditions

Fig. 6 shows the movement in the food insecurity status of the households during the 5 Waves. There was a gradual decrease in the households that ran out of money to buy food, from 51.7% in Wave 1–39.6% in Wave 5. The results were similar to van der Berg et al. (2021a) who found the gradual decrease of households who ran out of money to buy food from 47% in Wave 1–35% in Wave 5. Household that went without a meal decreased from 26.5% in Wave 1–19.1% in Wave 5. van der Berg et al. (2021a) also found household that went hungry decreasing from 23% to a fluctuation between 18% and 17%, between Waves 1 and 5. A modest change was observed for children in the households going hungry due to lack of food from 19.0% to 18.8% in Wave 2 and Wave 3, respectively, to 15.5% in Wave 5. van der Berg et al. (2021a) found that child hunger fluctuated between 15% and 14% between Waves 1 and 5. Furthermore, van der Berg et al. (2021a) concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the levels of the equilibrium levels of hunger and food insecurity in South Africa.

Fig. 6.

Households that have ran out of money to buy food; anyone in the house that has gone without a meal in 7 days; and any children in the household that have gone hungry due to lack of food.

Table 5 shows that there was a gradual increase in the indicator of running out of money to buy food from Wave 1 to Wave 5. This was also observed for the indicator relating to any children going hungry due to lack of food. The indicator relating to anyone going without a meal for 7 days abruptly increased in Wave 2 and then remained constant from thereon. An increase in the indicators show that there was an increase in food insecurity in the progression of the COVID-19 pandemic from Wave 1 to Wave 5. A study by Kansiime et al. (2021) in Kenya and Uganda found that the COVID-19 brought income shocks with a worsening food insecurity and dietary quality. This was due to limited disposable income to spend on food, augmented by food supply chain disruptions, resulting in food inflation (Kansiime et al., 2021). Amare et al. (2021) also found that in Nigeria, the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with significant increase in food insecurity due to mobility lockdowns which reduced labour market participation. Picchioni et al. (2021) avers that COVID-19 had direct effects on food insecurity through affecting employment, income and purchasing power.

Table 5.

Food insecurity indicators in the different Waves.

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ran out of money to buy food | N | 7018 | 5646 | 6094 | 5606 | 5842 |

| Mean | 0.4833 | 0.5953 | 0.5463 | 0.5803 | 0.6042 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.49976 | 0.49088 | 0.49789 | 0.49356 | 0.48905 | |

| Anyone gone without a meal in 7 days | N | 7016 | 5638 | 6108 | 5615 | 5857 |

| Mean | 0.7355 | 0.8090 | 0.7808 | 0.8082 | 0.8091 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.44112 | 0.39314 | 0.41375 | 0.39376 | 0.39303 | |

| Any kids gone hungry due to lack of food | N | 5658 | 4603 | 4610 | 4216 | 4343 |

| Mean | 0.8104 | 0.8625 | 0.8117 | 0.8430 | 0.8448 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.39205 | 0.34443 | 0.39098 | 0.36386 | 0.36213 |

Table 6 augments earlier findings of an increase in food insecurity in the progression of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant actions that were taken. The highest food insecurity condition was observed for Wave 2 with the highest food insecurity index, followed by Wave 5, Wave 4, Wave 3 and Wave 1, respectively. From this comparison, it shows that there was more food security in the initial phases of the COVID-19 lockdowns which decreased as the pandemic progressed.

Table 6.

Food insecurity indices from Wave 1 to Wave 5.

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std Error Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | 5598 | 0.6690 | 0.35375 | 0.00473 |

| Wave 2 | 4576 | 0.7478 | 0.32296 | 0.00477 |

| Wave 3 | 4579 | 0.7058 | 0.34510 | 0.00510 |

| Wave 4 | 4196 | 0.7340 | 0.34839 | 0.00538 |

| Wave 5 | 4326 | 0.7437 | 0.34840 | 0.00530 |

4.3. Mean differences in the food insecurity status of households in the 5 waves under COVID-19 conditions

There were significant mean differences in the food insecurity indices between Wave 5 and Wave 1 as well as Wave 5 and Wave 3 (Table 7 ). The positive mean value indicates that in both instances, the food insecurity status increased. There was a 7.47% increase in food insecurity between Waves 5 and 1, while there was a 3.80% increase in food insecurity between Waves 5 and 3. Contrary, van der Berg et al. (2021a) aver that food security in the households improved for some households, however hunger has not been abated. This is through some households recovering from the initial devastating effects of the pandemic, even though a large portion was still economically vulnerable. Furthermore, hunger and running out of money for food were shown not be inversely proportional (van der Berg et al., 2021a). The results are contrary to van der Berg et al. (2021a) because the latter utilised a descriptive analysis which was not inferential, tending to compare percentages. Interestingly however, a previous report by van der Berg et al. (2021b) has highlighted that there was a decrease in food insecurity, especially in Wave 2, which subsequently increased in Wave 3. The improvement in the food security status during Wave 2 can be attributed to the effect of the increased access to the COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) Grant which had been initiated in May 2020. The payment had initially been slow, but had peaked up to 2.4 million people in South Africa (Casale and Shepherd, 2020). The increase in food insecurity from Wave 2 can also be attributed to the ceasing of the SRD grant and the R500 top up to the Child Support Grants that was provided to caregivers by October 2020 (Casale and Shepherd, 2020; van der Berg et al., 2021b). van der Berg et al. (2021a) indicates that removal of the top ups to the Child Support Grants and the SRD in April 2021 will likely worsen the food insecurity caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 7.

Mean differences in the food insecurity indices based on Wave 5 base level.

| Levene's Test for Equality of Variance | t-test for equality of means | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig | Mean Difference | Std Error Difference | t | Sig | |

| Wave 1 | 2.404 | 0.121 | 0.07467*** | 0.00711 | 10.496 | 0.000 |

| Wave 2 | 23.536*** | 0.000 | −0.00409 | −0.00985 | −0.575 | 0.565 |

| Wave 3 | 2.526 | 0.112 | 0.03789*** | 0.00735 | 5.154 | 0.000 |

| Wave 4 | 0.134 | 0.714 | 0.00969 | 0.00755 | 1.283 | 0.199 |

The results are also comparable to Amare et al. (2021) who found that there were significant differences in the households that skipped a meal, ran out of food and went for a day without eating pre and post-COVID 19 in Nigeria. These changes were attributed to mobility restrictions and participation in income generating activities. In Kenya, Shupler et al. (2021) showed that household tended to change their food consumption patterns and had lower food availability as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This also caused household to shift their food supplier during the lockdown with an increase in household farming and livestock production as primary source of food.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The objective of the study was to ascertain the changes in the food security status of households during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study made use of secondary data obtained from the 5 Waves of the National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM). The majority of the respondents were Black/African female-headed households who held regular formal employment and resided in urban area/towns. Most of the respondents were formally employed in the community, social and personal services sector and child support grant was the most dominant for households that received social grants. The study found that there was a decrease in the households that ran out of money to buy food, households that had gone without a meal in the last 7 days and children who had gone hungry due to lack of food. However, the Min-Max normalisation indicators showed an increase in food insecurity from Wave 1 to 5. Significant differences in food security was observed between Wave 5 and Wave 1 as well as Wave 5 and Wave 3, which further showed an increase in food insecurity. The study concludes that there was initially food security which deteriorated as the pandemic progressed. Furthermore, even though some households were recovering from the initial devastating effects of the pandemic, a large portion were still economically vulnerable. In addition, the timing of some interventions by the South African government, such as increased access to the COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) Grant which had been initiated in May 2020 and the R500 top up to the Child Support Grants that was provided to caregivers by October 2020, also had an impact on food security.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is analogous to natural disasters which can be circumvented (or at least reduced) by mitigation and adaptation measures. Mitigation measures pre-empt and provide safety measures to counter food insecurity induced by the pandemic as well as build resilience. This includes promoting employment insurance to safeguard access to income during pandemics and disasters to ensure access to food. Short and localised value chains should be promoted to improve food accessibility during times of crisis. This tends to circumvent the logistical disruptions that are brought about by lockdown measures induced by disasters or pandemics and improve access to food. Re-energising homestead food garden programmes such as the Siyazondla Homestead Food Production Programme can help cut the long food value chains right to the doorstep, increasing the likelihood of having access to foods in times of crisis. This also reduces inequalities in accessing food resources which has been a precursor in household food insecurity relative to national food security.

Adaptation measures are ex-post and meant to cushion household against pandemics and natural disasters once they do occur. The study recommends a reconsideration of the scrapping of the top ups on the Child Support Grants as well as the SRD grant. The Child Support grants assists parents in lower income households with the costs of basic needs of their children, while the SRD grant was instituted to cushion against the effects of COVID-19 lockdowns on lost incomes. Scrapping the top ups will likely tighten the dire economic situation the households find themselves in and negatively affect household food security. There is need to expand the social safety nets to accommodate the vulnerable in society. In addition to other new grants such as the SRD and topping up of the Child Grants, food assistance programmes should be promoted such as the school nutritional programmes but at household levels. This will help insulate low income households and aid in reducing food insecurity. However, this also brings sustainability issues post-COVID-19 to cushion affected household against food insecurity.

The study contributes to empirical perspectives on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food insecurity in the midst of opinion pieces and conceptual papers especially in developing countries. Further areas of inquiry that can be pursued to augment the study are simulating the effects of the targeted safety nets on rural and urban households as their food insecurity situations, mitigation and adaptation measures differ. Comprehensive food security measures such as the Household Food In-Access Scale (HFIAS), Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) and Food Consumption Score (FCS) can be explored to provide comprehensive measures of food security and how the pandemic had an effect. Further empirical studies incorporating treatment effects or difference-in-difference can further explore the impact of the pandemic on food security, pre-, during and post-COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

Data used in the study can be obtained from (1) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2021a. Wave 5 [dataset]. Version 1.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/awhe-t852; (2) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2021b. Wave 4 [dataset]. Version 2.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/y5qj-x095; (3) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2020a. Wave 3 [dataset]. Version 3.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/s82x-nx07; (4) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2020b. Wave 2 [dataset]. Version 3.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/5z2w-7678; and (5) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2020c. Wave 1 [dataset]. Version 3.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/7tn9-1998.

Author contributions

Saul Ngarava was involved with conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology project administration, data curation and writing the original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Amare M., Abay K.A., Tiberti L., Chamberlin J. COVID-19 and food security : panel data evidence from Nigeria. Food Pol. 2021;101 doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt C., Davies R., Gabriel S., Harris L., Makrelov K., Robinson S., Levy S., Simbanegavi W., van Seventer D., Anderson L. Covid-19 lockdowns, income distribution, and food security: an analysis for South Africa. Global Food Secur. 2020;26 doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin-ragaven L. Social dimensions of COVID-19 in South Africa : a neglected element of the treatment plan. Wits J. Clin. Med. 2020;2:33–38. doi: 10.18772/26180197.2020.v2nSIa6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Béné C., Bakker D., Chavarro M.J., Even B., Melo J., Sonneveld A. Global assessment of the impacts of COVID-19 on food security. Global Food Secur. 2021;31 doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale D., Shepherd D. 2021. The Gendered Effects of the COVID-19 Crisis and Ongoing Lockdown in South Africa: Evidence from NIDS-CRAM Waves; pp. 1–5. Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Casale D., Shepherd D. vols. 1 and 2. 2020. (The Gendered Effects of the Ongoing Lockdown and School Closures in South Africa: Evidence from NIDS-CRAM Waves). (Cape Town, South Africa) [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos F., Hernandez M.A., Paz C. Short-term impacts of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition in rural Guatemala: phone-based farm household survey evidence. Agric. Econ. 2021;52:477–494. doi: 10.1111/agec.12629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S., Kramers-olen A.L. COVID-19 , inequality , and the intersection between wealth , race , and gender. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2021;51:195–198. doi: 10.1177/00812463211015517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crush J., Si Z. COVID-19 containment and food security in the Global South. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2020;9:149–151. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2020.094.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Klerk M., Drimie S., Aliber M., Mini S., Mokoena R., Randela R., Modiselle S., Vogel C., de Swardt C., Kirsten J. 2004. Food Security in South Africa: Key Policy Issues for the Medium Term. (Pretoria, South Africa) [Google Scholar]

- Department of National Treasury . 2020. Economic Measures for COVID-19. (Pretoria, South Africa) [Google Scholar]

- Devereux S., Béné C., Hoddinott J. Conceptualising COVID-19’ s impacts on household food security. Food Secur. 2020;12:769–772. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01085-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DoH . 2020. Update on COVID-19.https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2020/05/09/update-on-covid-19-9th-may-2020/?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=50f7bf124a8eafbdae33215d56c0ac668f38ad89-1589053657-0-AfZkD22KgaVeSj9QPNZ6c7H-kwx-Y4pyZbq-XNH_W3Qtvv8Hd0T8zSmYgzWR7FitcuvTyJ2_K2xciZM0f0cp6I9qrtjmfnIRnZsxdh6VTcgGW 9th May, 2020) [WWW Document]. COVID-19 Online Resour. News Portal. URL. 4.16.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsahoryi N., Al-Sayyed H., Odeh M., McGrattan A., Hammad F. Effect of Covid-19 on food security: a cross-sectional survey. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2020;40:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N. Economic effects of coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) on the world economy (No. Working Paper No. WP-1240-E) 2020. Barcelona. [DOI]

- Folayan M.O., Ibigbami O., Tantawi M. El, Brown B., Aly N.M., Ezechi O., Abeldaño G.F., Ara E., Ayanore M.A., Ellakany P., Gaffar B., Al-khanati N.M., Osamika B.E., Faeq M., Quadri A., Roque M., Al-tammemi A.B., Yousaf M.A., Virtanen J.I., Ariel R., Zuñiga A., Okeibunor J.C., Nguyen A.L. Factors associated with financial security, food security and quality of daily lives of residents in Nigeria during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. Artic. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D., Valodia I., Webster E. Politics, policy, and inequality in South Africa under COVID-19. Agrar. South J. Polit. Econ. 2020;9:342–355. doi: 10.1177/2277976020970036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- GoSA . 2020. Declaration of National Disaster. Pretoria, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- GoSA . 2020. Minister Zweli Mkhize Confirms 13 More Coronavirus COVID-19 Cases in South Africa.https://www.gov.za/speeches/dr-zweli-mkhize-confirms-latest-coronavirus-covid-19-cases-south-africa-15-mar-2020-0000 [WWW Document]. South African Gov. URL. 5.9.20. [Google Scholar]

- GoSA . 2020. Small Business Development: Measures to Prevent and Combat the Sptread of COVID-19. Pretoria, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Govinden K., Pillay S., Ngobeni A. 2020. Business Impact Survey of the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Groot J. De, Lemanski C. COVID-19 responses: infrastructure inequality and privileged capacity to transform everyday life in South Africa. Environ. Urbanization. 2020;33:255–272. doi: 10.1177/0956247820970094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inegbedion H.E. COVID-19 lockdown: implication for food security. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2021;11:437–451. doi: 10.1108/JADEE-06-2020-0130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingle K., Brophy T., Daniels R. 2021. National Income Dynamics Study - Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM) 2020-2021 Panel User Manual. Version 1. Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- IPC . 2021. South Africa: IPC Acute Food Insecurity Analysis, September 2020 - March 2021. Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Jaacks L.M., Veluguri D., Serupally R., Roy A., Prabhakaran P., Ramanjaneyulu G. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural production, livelihoods, and food security in India: baseline results of a phone survey. Food Secur. 2021;13:1323–1339. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01164-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansiime M.K., Tambo J.A., Mugambi I., Bundi M., Kara A., Owuor C. COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda : findings from a rapid assessment. World Dev. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleve S., Bennett C.J., Davidson Z.E., Kellow N.J., Mccaffrey T.A., Reilly S.O., Enticott J., Moran L.J., Harrison C.L., Teede H., Lim S. Food insecurity prevalence , severity and determinants in Australian households during the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of women. Nutrients. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/nu13124262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laborde D., Martin W., Vos R. Impacts of COVID-19 on global poverty, food security, and diets: insights from global model scenario analysis. Agric. Econ. 2021;52:375–390. doi: 10.1111/agec.12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed E.M.A., Abdallah S.M.A., Ahmadi A., Lucero-Prisno D.E., III Food security and COVID-19 in africa : implications and recommendations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;104:1613–1615. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley W.G., Battersby J. The vulnerability and resilience of African food systems, food security, and nutrition in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Afr. Rev. 2020;63:449–461. doi: 10.1017/asr.2020.72. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM) 2021. Wave 5. Version 1.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM) 2021. Wave 4. Version 2.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM) 2020. Wave 3. Version 3.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM) 2020. Wave 2. Version 3.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM) 2020. Wave 1. Version 3.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ngarava S., Mushunje A., Chaminuka P. Qualitative benefits of livestock development programmes. Evidence from the Kaonafatso ya Dikgomo (KyD) Scheme in South Africa. Eval. Progr. Plann. 2020;78 doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2019.101722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngarava S., Zhou L., Ningi T., Chari M.M., Mdiya L. Gender and ethnic disparities in energy poverty : the case of South Africa. Energy Pol. 2022;161 doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NICD . 2020. First Case of COVID-19 Coronavirus Reported in SA. Johannesburg, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu C.O., Oyenubi A. Income-related health inequalities associated with the coronavirus pandemic in South Africa : a decomposition analysis. Int. Journl Equity Heal. 2021;20:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01361-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odunitan-wayas F.A., Alaba O.A., Lambert E.V., Alaba O.A., Lambert E.V. Food insecurity and social injustice : the plight of urban poor African immigrants in South Africa during the COVID-19 crisis. Global Publ. Health. 2021;16:149–152. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1854325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwatayo I.B. Towards assuring food security in South Africa : smallholder farmers as drivers. AIMS Agric. Food. 2019;4:485–500. doi: 10.3934/agrfood.2019.2.485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pakravan-Charvadeh M.R., Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F., Gholamrezai S., Vatanparast H., Flora C., Nabavi-Pelesaraei A. The short-term effects of COVID-19 outbreak on dietary diversity and food security status of Iranian households (A case study in Tehran province) J. Clean. Prod. 2021;281 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick H.O., Khalema E.N., Abiolu O.A., Ijatuyi E.A., Abiolu R.T. South Africa’ s multiple vulnerabilities, food security and livelihood options in the COVID-19 new order : an annotation. J. forTransdisciplinary Res. South. Africa. 2021;17:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Picchioni F., Goulao L.F., Roberfroid D. The impact of COVID-19 on diet quality , food security and nutrition in low and middle income countries : a systematic review of the evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay R., Scheepers C.B. Response of department of transport to food security in South Africa: leading agility during COVID-19. Emerald Emerg. Mark. Case Stud. 2020;10:1–23. doi: 10.1108/EEMCS-06-2020-0224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PKF South Africa . 2020. Lockdown's Impact on Your Business. Johannesburg, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.T., Akter S., Rana M.R., Sabuz A.A., Jubayer M.F. How COVID-19 pandemic is affecting achieved food security in Bangladesh: a perspective with required policy interventions. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022;7 doi: 10.1016/j.jafr.2021.100258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raidimi E.N., Kabiti H.M. A review of the role of agricultural extension and training in achieving sustinable food security: a case of South Africa. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2019;47:120–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszczyk H.A., Rahman M.F., Bracken L.J., Sudha S. Contextualizing the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on food security in two small cities in Bangladesh. Environ. Urbanization. 2021;33:239–254. doi: 10.1177/0956247820965156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shupler M., Mwitari J., Gohole A., Anderson de Cuevas R., Puzzolo E., Čukić I., Nix E., Pope D. COVID-19 impacts on household energy & food security in a Kenyan informal settlement: the need for integrated approaches to the SDGs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021;144 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.111018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyn F., Klopper H. Why government must lift the ban on tobacco sales - UP experts weigh in. 2020. https://www.up.ac.za/news/post_2892092-in-my-opinion-why-government-must-lift-the-ban-on-tobacco-sales-up-experts-weigh-in WWW Document]. Univ. Pretoria. URL. 5.4.20.

- Tsakok I. Food security in the context of COVID-19: the public health challenge. The case of South Africa. 2020 Rabat, Morocco. [Google Scholar]

- van der Berg S., Patel L., Bridgman G. vol. 5. 2021. (Food Insecurity in South Africa: Evidence from NIDS-CRAM Wave). Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- van der Berg S., Patel L., Bridgman G. 2021. Hunger in South Africa during 2020: Results from Wave 3 of NIDS-CRAM. Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- van Walbeek C., Filby S., van der Zee K. Lighting up the illicit mrket: smoker's responses to the cigrette sales ban in South Africa. Research Unit on the Economics and Excisable Products (REEP) 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C.M., Rooyen F.C. Van, Walsh C.M. Household food security and hunger in rural and urban communities in the Free State Province , South Africa. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2015;54:118–137. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2014.964230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegerif M.C.A. Informal ” food traders and food security : experiences from the Covid-19 response in South Africa. Food Secur. 2020;12:797–800. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01078-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workie, E., Mackolil, J., Nyika, J., Ramadas, S., 2020. Deciphering the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food security, agriculture, and livelihoods: A review of the evidence from developing countries. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2, 100014. 10.1016/j.crsust.2020.100014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Worldometer COVID-19 Coronvirus pandemic. 2021. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?utm_campaign=homeAdvegas1?%22 WWW Document]. URL. 7.26.21.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in the study can be obtained from (1) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2021a. Wave 5 [dataset]. Version 1.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/awhe-t852; (2) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2021b. Wave 4 [dataset]. Version 2.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/y5qj-x095; (3) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2020a. Wave 3 [dataset]. Version 3.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/s82x-nx07; (4) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2020b. Wave 2 [dataset]. Version 3.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/5z2w-7678; and (5) National Income Dynamics Study-Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (NIDS-CRAM), 2020c. Wave 1 [dataset]. Version 3.0.0. Cape Town, South Africa. https://doi.org/10.25828/7tn9-1998.