Abstract

Wellness is more than the simple absence of disease. As such, health can be envisioned as a journey to a state of optimal wellness and not a simple destination. To measure progress on such a journey, defining wellness by measures other than disease risk factors and biomarkers is necessary. Health can be defined by five areas of functionality: metabolic, physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral. Indeed, an individual’s behaviors are the outward expression of an inward integration of the metabolic, physical, emotional, and cognitive functions in a fully actualized mind, body, and spirit. Personalized Lifestyle Medicine recognizes the importance of facilitating lasting behavioral change but facilitating this change may be difficult and may resist standard practice models. It is our proposal that a major obstacle on the journey to achieving full wellness is the brokenness of an individual’s connections to self, to purpose, to community, and to the environment. Programs aimed both at defining an individual’s authentic self and providing patient education using Functional Medicine’s unique philosophy can facilitate a patient’s creation of a lasting vision that is the work of successful behavioral change.

Introduction

It is an accepted tenet of Integrative Medicine, of Functional Medicine, of P4 Medicine, and of Personalized Lifestyle Medicine that wellness is more than the simple absence of disease. When a patient awakens on a Monday morning with crushing chest pain while preparing for their busy day and subsequently receives a new diagnosis of angina and coronary artery disease, it is clear that the dysfunction driving a disease-defining pathophysiology has been present for an extended period.

Addressing the epidemic of noncommunicable chronic diseases requires an appreciation of this preclinical window of disrupted physiology that progresses to expressed pathophysiology. Personalized Lifestyle Medicine, incorporating features of functional medicine, P4 medicine, naturopathy and allopathic medicine, uses a patient-centered, longitudinal assessment of functional health status to focus efforts on prevention of disease occurrence and modification of disease progression.

Certainly, in his valedictory speech at the University of Pennsylvania in 1889, Sir William Osler might have said it best: “Our study is man, as the subject of accidents or disease. Were he always, inside and outside, cast in the same mould, instead of differing from his fellow man as much in constitution and in his reaction to stimulus as in feature, we should ere this have reached some settled principles in our art.”1

Despite not having reached “some settled principles” as practitioners, we strive to understand our patients (The authors recognize the limitations of the word patient; indeed, some of the authors aren’t able to use the word patient and instead use the word client. Perhaps participant, a word that has been replacing patient or subject in recent clinical trials, is a better alternative. Each of these words have their limitations, and thus, for clarity and simplicity, the authors have chosen to use patient in this article) and make both our diagnoses and treatments relevant. The 4 Ps of P4 medicine—personalized, predictive, preventive, and participatory—provide a useful focus.

Personalized care requires recognition of the individual’s uniqueness and the disease that they have. Participatory requires creating an equal partnership with the patient, both acknowledging their autonomy and requiring their responsible leadership in lifestyle change. Predictive and preventive care requires identification of a patient’s current status to allow personalized interventions to be meaningfully applied. To ensure the relevancy of a practitioner’s recommendations regarding lifestyle change, it becomes necessary to define health and wellness by measures other than the standard identification of disease risk factors and disease biomarkers.

Cassell2 has noted that “Patients have a sense of well-being when they are able to pursue their purposes and achieve their goals in life’s various domains.” To pursue purpose and achieve goals, an individual must have the ability to perform their functions and activities of daily living vitally. To measure this ability, clinicians and researchers can now collect and analyze data, including functional testing—both clinical assessments and wearable devices, advanced laboratory biomarkers of cardiovascular and hormonal status, genomic testing, microbiome testing, and exposome testing. However, in a discussion of data analysis methodologies for these aggregated sets of individual patients’ data, Price3 has identified a lack of clear boundaries between the definitions of disease, average health, and optimal well-being. This lack presents a significant challenge to the practical use of this data to draw distinctions between the lack of disease and optimal well-being in an individual.

The exploration of functionality as a measure that gives definition to those boundaries has been discussed by Hanaway4 and Bland.5 The Doetinchem Cohort Study evaluated frailty in adults, aged 40 to 81 years, and concluded that defining physical, cognitive, and emotional function permitted personalization and increased the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions.6 In 2017, Bland, Minich, and Eck described an approach to improving individual health and wellness using systems biology and unique functional assessments to improve the effectiveness of lifestyle medicine.7

Bland8 has identified four unique subgroups of function, specifically metabolic, physical, emotional, and cognitive. These four functions can be directly viewed, assessed, and quantified through the compilation and analysis of de-identified collections of detailed patient histories, questionnaires regarding symptoms and general condition, and associated objective findings, such as genomic data, vital signs, physical examinations and laboratory biomarkers.

Metabolic functions are hidden to the human eye without the use of microscopes or biochemical assays but are assessable with standard laboratory biomarkers and imaging techniques. Ideally, laboratory evaluations would include basic chemistries and blood counts, advanced lipid panels, inflammatory markers, nutritional markers, single nucleotide polymorphism analyses, and stool microbiome assessment.

Physical functions are macroscopic, viewable by the human eye and measurable. These measures include expiratory peak flow, grip strength, balance, gait timed up and go, vision, taste perception and smell as well as extensive anthropometric measurements and a nutrition-targeted physical examination.

Cognitive and emotional functions can be well understood by selecting from the extensive array of standardized questionnaires available to practitioners and researchers. Among the broad range of questionnaires, the Rand MOS quality of life survey, the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (MOS SF-36);9 measures of mood and stress such as the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS),10 Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),11 and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI);12 the National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) questionnaires;13 and the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Scale (URICA)14 can contribute to a deeper understanding of a patient’s uniqueness, which can foster the development of a personalized lifestyle medicine program.

Behavior: An Outward Expression

Stein15 summarizes Carl Jung’s characterization of an individual’s inner subjective experience of their psyche as the integration of ego-consciousness, complexes, libido, archetypes, shadow, animus or anima, and self. In his Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy,16 Wilber quantifies human experience to draw distinctions between intentional (subjective), behavioral (objective), cultural, and social perspectives.

As clinicians and researchers, we do not see, nor can we measure accurately an individual’s inner experience. Instead, we attempt to objectively listen, take detailed histories, do physical and laboratory evaluations, and in functional medicine, tell the person’s story back to him or her.

One of the practical tools taught by the Institute for Functional Medicine is GO-TO-IT representing “gather, organize, tell (back), order, initiate, and track.” This model encourages both the clinician and the patient to see the patterns of the past that have promoted health or disease and to project a plan for the future. Ultimately, we draw conclusions based on observing a patient’s past and current actions. Given Merriam-Webster’s definition of behavior as “the way a person or animal acts or behaves,”17 the actions that we observe are a patient’s behavior.

Many of our (practitioners and patients, alike) behaviors seem automatic; indeed, they become hardwired due to plasticity and often are beyond our ken when it comes to describing how we do what we do. If challenged to describe how to ride a bike or to gather words to teach someone to ride a bike, many would experience difficulty with the task. Defining each step, what comes next, what we are sensing, initiating, doing, and integrating to keep us upright and the bike rolling is anything but easily expressed in words. Yet once we learn how to do it, it is as simple as riding a bike.

While behaviors may be automatic, they are not necessarily instinctual, we don’t come equipped with all necessary programming at birth. Instead, we gain experience, learnings and functions, that enable us to behave as we choose.

The potential offered by neuroplasticity to form new synaptic connections is essential for changes in perspective and behaviors. Personal lifestyle choices—sleep, exercise, nutrition, thoughts and emotions, and societal and personal relationships—influence neurotrophic factors that affect the survival, growth and veracity of novel neural connections. By making new connections between neurons, neurogenesis within existing networks occurs, thus changing the activity in specific regions of the brain and reshaping the networks.

Hansen18 notes that consciously repeated behaviors with resulting growth or pruning of neuronal connections changes the neural networks, increasing the ease of adapting new behaviors; specifically, he says “Our neuroplasticity allows the mind to change the brain to change the mind.”

The influence of repeated practice on neuroplasticity and the creation of automatic behaviors that increase an individual’s functionality may be analogous to ceremony as “a formal act or series of acts prescribed by ritual, protocol, or convention”19 that increase a group’s functionality.

Hobson et al20 note three regulatory functions of ritual: regulation of emotions, of performance goal states, and of social connection. Sacrament, a specific class of religious ceremony or behavior, has been defined as “the outward and visible sign of an inward and invisible grace.”21 Thus, we may say that behaviors are the outward expression of an internal integration of metabolic, physical, emotional, and cognitive functions in a fully actualized mind, body, and spirit.

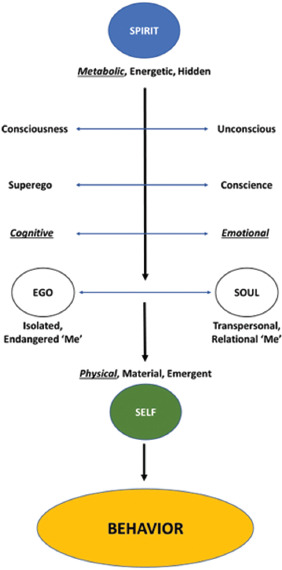

Accepting that definition, practitioners may recognize the tension between what they have defined as functions and the subtle and not so subtle influences on how individuals express and value their behaviors. Behaviors thus become meaningful as an outward expression of functional capacity and a balance of interior psychological processes - hidden versus emergent, cultural and societal versus personal values, and soul versus ego. The breadth of inputs influencing the output called behavior is presented in Figure 1, which shows the four functions—metabolic, physical, cognitive, and emotional—integrated into a proposed model of self.

Figure 1.

Interaction of the Four Physiologic Functions - Metabolic, Physical, Cognitive, and Emotional. Figure 1 shows the authors’ model of self that is consistent with Wilber’s integral psychology approach. Many factors can influence the motivation and ability to perform a behavior. Behaviors are meaningful as an outward expression of functional capacity and of a balance of interior psychological processes - hidden versus emergent, soul versus ego, and cultural versus personal values.

Behavioral Change

A challenge for all, practitioners and patients alike, is that their behaviors frequently do not serve them. Many behaviors, whether distractions, detours, or relapses, complicate a journey to wellness. Personalized lifestyle medicine recognizes the importance of facilitating lasting behavioral change.

Facilitating that change may be difficult, however. Lack of integrated programs in standard allopathic settings illuminate the gaps in standard motivational and behavioral models, and patients fail to achieve lasting change. One obstacle is the failure to recognize the patient’s readiness to change.

Prochaska et al22 have demonstrated that patients can be unaware of the need for change, be unprepared or undermotivated to make the change, and when change occurs are vulnerable to relapse. Fortunately, those researchers’ model has demonstrated that effective techniques are available to use at each identified stage.

Other obstacles may include lack of knowledge regarding the benefits of change or of effective techniques for change, cognitive dissonance, and primary and secondary gains associated with troublesome behaviors.

Communication styles employed by practitioners may also be problematic. Allopathic physicians, advanced practice nurses, and physician assistants frequently first learn their communication skills in the acute-care setting. Telling patients what to do or motivating them through fear may be efficacious in the setting of acute appendicitis, but those skills don’t transfer well when applied to chronic health challenges.

Just as therapeutic models appropriate for acute care propagate a “pill for an ill” approach to chronic disease, the way practitioners communicate, especially in a timebound, traditional 15-minute visit, may also be ineffective in producing lifestyle change. This can lead to an unfortunate cycle of ineffective communication, lack of effective behavioral change, no change in the biomarker that is driving the need for change, and finally, a reinforced belief by practitioner and patient that lifestyle change doesn’t work. Hence, a practitioner’s perception of the limited efficacy of lifestyle-change programs encourages a default prescribing of medications rather than of lifestyle change and the patient’s default acceptance of a prescription.

Advances in the lifestyle-education coaching model forwarded by the Functional Medicine Coaching Academy and reviewed by Phillips et al23 would suggest that failure to promote successful lifestyle change can be attributed to ineffective communication. Frates24 notes that the more an expert surrenders his or her expertise in the change conversation and truly communicates unconditional positive regard for an individual’s autonomy, the greater the opportunity for the client’s motivation to emerge.

Practitioners cannot tell others what they need to change or what they should do; instead, change needs to be self-directed. And behaviors are not good or bad; they are instead functional or dysfunctional, with functionality being measured by the degree to which they make the journey to wellness an easier path to navigate. Integrated care teams, consisting of practitioners, clinician extenders, nutrition professionals, social workers, and health coaches,25 and group medical visits26 are two models demonstrating efficacy in promoting behavioral change.

The ineffectiveness of the paradigm that practitioners can command or motivate successful behavioral change, has led researchers to explore what can indeed work. Fogg27 has demonstrated the effectiveness of making behaviors simple and tying them to established triggers to create new behaviors. His practice addresses the challenge of unhealthy behaviors by crowding them out with preferred behaviors.

Importance, Meaning, and Value

Many practitioners and patients have had the experience of making lifestyle changes, perhaps even recognizing the benefits, yet witnessing the return of old patterns of behavior. Despite one’s best intentions, many journeyers find challenges to successful long-term implementation of change.

New behaviors must compete with established needs for energy, time, and resources. External demands, cultural and societal messages, and life events, all may create threats to the ego’s strong yearning for the status quo. Or perhaps desired results may not have been enough or new behaviors left us unsatisfied; so, old behaviors called, and we responded.

Maslow has established a hierarchy of needs28—physiological needs, safety needs, love and belonging needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization needs—that influence an individual’s behaviors. Thus, lacking energy, time, and resources for behavioral change represents a failure to satisfy basic physiological and safety needs. Establishing successful change may be difficult despite meeting these basic needs due to emotional and psychological struggles in higher hierarchical states.

We propose that a major obstacle to achieving full wellness is the brokenness of the connection to the self and of the self to the community and the environment. Young children, when asked, express their dreams of being an astronaut, ballerina, quarterback, president, nurse, doctor, teacher, scientist, stockbroker, soldier, or movie star; they dream large. It is unlikely that any child ever wished to be the unknown, fifth row back, fourth cubicle over, in a grey, sullen workplace.

Patients and practitioners dream of being Joseph Campbell’s hero venturing “… forth from the world of common-sense consciousness into a realm of supernatural wonder. There he encounters fabulous forces—demons and angels, dragons and helping spirits. After a fierce battle, he wins a decisive victory over the powers of darkness. Then he returns from his mysterious adventure with the gift of knowledge or of fire, which he bestows on his fellow man.”29

While Murdock30 has addressed the danger of sexist archetypes and toxic masculinity in the classic Hero’s Journey model, it is clear that the larger danger with the archetype of hero today is the distortion that the sought-after rewards are the accoutrements of financial success and power. Today’s culture of toxic consumerism generates ill health on all levels, from a single-celled organism to a planetary level.31

Many people, practitioners and patients alike, are unconsciously drawn, however, to an integrative journey where they may realize their unique purpose for existence and their reward is the sharing of the received gifts and accomplishments with fellow beings. Whether it may be writing the great American novel, addressing climate change, or simply remembering to be a compassionate neighbor, each individual can be called to journey.

Wilber16 notes: “Whenever we moderns pause for a moment and enter the silence, and listen very carefully, the glimmer of our own deepest nature begins to shine forth, and we are introduced to the mysteries of the deep, the call of the within, the infinite radiance of a splendor that time and space forgot—we are all introduced to the all-pervading Spiritual domain that the growing tip of our honored ancestors were the first to discover.”

As a patient is drawn by spirit to a reclamation of their life’s purpose and authentic self, practitioners need to aid them in assessing “What is important, meaningful and valuable” in their lives. This can be achieved through the use of coaching, guided imagery, and journaling techniques that have early roots in the work of Simon.32 Ultimately, what makes a behavior simple is the degree that it resonates with a vision that patients choose and can state.

In reclaiming their life’s purpose, patients are creating the opportunity to improve their health by consciously choosing a journey to wellness. Keen and Valley-Fox state: “To remain vibrant throughout a lifetime, we must always be inventing ourselves, weaving new themes into our life narratives, remembering our past, re-visioning our future, reauthorizing the myth by which we live.”33

Scott et al34 have found that a patient’s acknowledgment of wounding and suffering, development of helping relationships, and acquisition of resources are key components of a therapeutic model (Figure 2) to facilitate healing and the recovery of wellness.

Figure 2.

Acknowledgment of Suffering as an Impediment to Wellness and Healing. Developing helping relationships and acquiring resources are key components of a therapeutic model that values safety, persistence, and trust to facilitate healing and the recovery of wellness. (With permission from the NOVA Institute for Health of People, Places, and Planet.)

Debusk et al have published a detailed description of their work integrating a systems-biology approach to behavioral health.35 Invaluable resources include Gordon’s training program36 at the Center for Mind Body Medicine in Washington, DC which trains practitioners to assist their patients on their health journey as does the program at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine.37 Snapp, Debusk, and Stone at the University of Georgia, in their work with medical students and residents, have demonstrated changes in practitioner well-being with similar programs (Personal communication to first author of work in press).

We propose that programs aimed both at defining an individual’s authentic self and at providing patient education using Functional Medicine’s philosophy, are uniquely suited to the re-creating, visioning, and new behavior adaptation that is the work of successful behavioral change. To wholly participate in a patient’s journey, practitioners must actively engage in their own self-discovery and drive to wellness. (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Trainings, Retreat Centers and Books for a Practitioner’s Journey of Self-Discovery

| Trainings: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Center | Location | Website |

| Institute for Functional Medicine | Federal Way, WA | https://www.ifm.org/ |

| Center for Mind Body Medicine | Washington, DC | https://cmbm.org/ |

| Functional Medicine Coaching Academy | Chicago, IL | https://functionalmedicinecoaching.org/ |

| Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at MGH | Boston, MA | https://bensonhenryinstitute.org/ |

| Retreat Centers: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Center | Location | Website |

| Esalen Institute | Big Sur, CA | https://www.esalen.org/ |

| Feathered Pipe Ranch | Helena, MT | https://featheredpipe.com/ |

| Omega Institute | Rhinebeck, NY | https://www.eomega.org/ |

| Books: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Title | Publisher | Date |

| Jeffrey Bland | The Disease Delusion: Conquering the Causes of Chronic Illness for a Healthier, Longer, and Happier Life | Harper Wave | 2015 |

| James Gordon | Transforming Trauma: The Path to Hope and Healing | Harper One | 2021 |

| Bill Plotkin | Soulcraft: Crossing into the Mysteries of Natures and Psyche | New World Library | 2010 |

| Pierre Teilhard de Chardin | The Divine Milieu. | Harper Perennial Modern Classics | 2001 (originally published 1957) |

| Bessel Van Der Kolk | The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma | Penguin Books | 2014 |

| Ken Wilber | Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy | Shambhala | 2000 |

Modeling programs of self-discovery that are typical of integral psychology as well as extensive patient education about the modifiable personal lifestyle factors which are the base of the Functional Medicine Matrix,38 the Consilience Partnership team—Lamb, Stone, Class, Buell, Suiter, and Heller—have conducted Functional Medicine Journey retreats at the Rivendell Spiritual Center in Sewanee, Tennessee, the Harmony Hill Healing Retreat in Union, Washington and the Feathered Pipe Ranch in Helena, Montana. Attendees at these retreats participated in didactic and experiential large groups exploring lifestyle-change strategies using the Functional Medicine Matrix and Timeline and attended small groups involved in mind-body-spirit skill building and therapeutic activities. The Consilience Partnerships experience has demonstrated that participants’ self-discovery, supportive coaching, patient education, and development of new and practical cognitive behavioral skills, coupled with supportive technologies, such as social-media support and virtual communities, foster lasting change.

Service and Creation of Community

As patients explore their understanding of their wellness journey and the factors influencing their behaviors, they may recognize the role of spirit in creating their uniqueness and self-worth. William Stafford,39 writing just a few days before his death and perhaps equating presence with now and self-awareness, asked: “What can anyone give you greater than now, starting here, right in this room, when you turn around.”

Just as practitioners surrender their expertise to facilitate a patient’s autonomy, practitioners should not define spirit, instead leaving patients to experience and name the spark that perhaps defines humanness.

In the Consilience Partnership work, participants are challenged to look for this spark in others, after first finding it in themselves. And all of us, upon finding that spark in those whom we meet, owe them, as Pope Francis reminded us, our “respect and reverence”40 and our service. Showing compassion and providing service to all those around us will change the world we see. Viewing our communities and the planet in this fashion may bring us closer to our full actualization as a person.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit paleontologist, wrote: “Someday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides, and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love and then, for a second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire.”41 Perhaps the greatest gift, our work, research, and programs can give us and our patients is the sense that we are all in this journey together.

References

- 1.Osler Wm. Aequanimitas with Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. P. Blakiston’s Son & Co, Philadelphia, 1914. p.35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassell EJ. The Nature of Healing: The Modern Practice of Medicine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price ND, Magis AT, et al. A wellness study of 108 individuals using personal, dense, dynamic data clouds. Nature Biotechnology. 2017; 35:747-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanaway P. Form follows function: A functional medicine overview. Perm J. 2016; 20(4):125-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bland J. Defining function in the functional medicine model. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2017; 16(1):22-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Oostrom SH, van der A DL, Rietman ML, et al. A four-domain approach of frailty explored in the Doetinchem Cohort Study. BMC Geriatr. Aug 30, 2017; 17(1):196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bland JS, Minich DM, Eck BM. A systems medicine approach: Translating emerging science into individualized wellness. Adv Med. 2017; 2017:1718957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bland JS. Systems biology meets functional medicine. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2019; 18(5):14-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck A.T., Ward C.H., Mendelson M., Mock J., Erbaugh J. An Inventory for Measuring Depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parkitny L., McAuley J. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) J. Physiother. 2010;56:204. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(10)70030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck A.T., Steer R.A. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. J. Clin. Psychol. 1984;40:1365–1367. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198411)40:6<1365::AID-JCLP2270400615>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck A.T., Epstein N., Brown G., Steer R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella D., Yount S., Rothrock N., Gershon R., Cook K., Reeve B., Ader D., Fries J.F., Bruce B., Rose M. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med. Care. 2007;45((Suppl. S1)):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Field C.A., Adinoff B., Harris T.R., Ball S.A., Carroll K.M. Construct, concurrent and predictive validity of the URICA: Data from two multi-site clinical trials. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein M. Jung’s Map of the Soul. Chicago and La Salle, IL: Open Court Publishing, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilber K. Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy. Boston and London: Shambhala, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merriam-Webster On-line Dictionary; https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/behavior, accessed 29 October 2021.

- 18.Hansen R. Neurodharma: New Science, Ancient Wisdom, and Seven Practices of the Highest Happiness. New York, NY: Harmony Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merriam-Webster On-line Dictionary; https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ceremony, accessed 21 November 2021.

- 20.Hobson NM, Schroeder J, et al. The psychology of rituals: An integrative review and process-based framework. Pers Soc Psych Rev. 2018: 22(3): 260-86. DOI:10.1177/1088868317734944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holcomb JS, Johnson DA. Christian Theologies of the Sacraments: A Comparative Introduction. New York, NY: NYU Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prochaska JO, Norcross J, DiClemente C. Changing for Good: A Revolutionary Six-Stage Program for Overcoming Bad Habits and Moving Your Life Positively Forward. New York, NY: Avon Books, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips EM, Frates EP, Park DJ. Lifestyle medicine. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2020; 31(4):515-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frates EP. Health coaching: Changing the delivery of health care. Altern Complement Therapies Health Med. 2018; 24(6):250-2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henwood BF, Siantz E, et al. Advancing integrated care through practice coaching. Int J Integr Care. 2020; 20(2):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frates EP, Morris EC, et al. The art and science of group visits in lifestyle medicine. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2017; 11(5):408-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fogg BJ. Tiny Habits: The Small Changes that Change Everything. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH) Books, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 1943; 50(4);370-96. 10.1037/h0054346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keen S. Man and myth: A conversation with Joseph Campbell. Psychology Today. 1971; 5:35-9, 86-95. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murdock M. The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness, 30th Anniversary Edition. Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala Publications, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prescott SL, Logan AC. Planetary health: From the wellspring of holistic medicine to personal and public health imperative. Explore. 2019; 15(2):98-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon SB. Promoting the search for values. Sch Health Rev. 1971; 2(1):21-4. PMID: 5206291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keen S, Valley-Fox A. Your Mythic Journey. New York, NY: TarcherPerigee, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott JG, Warber SL, Dieppe P, Jones D, Strange KC. Healing journey: A qualitative analysis of the healing experiences of Americans suffering from trauma and illness. BMJ Open. 2017; 0:e016771. Doi 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeBusk R, Snapp CA. “A Systems Medicine Approach to Behavioral Health in the Era of Chronic Disease,” in The Behavioral Health Specialist in Primary Care. New York. NY: Springer, 2015, pp. 291-309. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Staples JK, Gordon JS. Effectiveness of a mind-body skills training program for health-care professionals. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005; 11(4):36-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trager l, Styklunas GM, Park EY, et al. Promoting resilience and flourishing among older adult residents in community living: A feasibility study. Gerontologist. 2022. Mar 2;gnac031. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac031. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones DS, Quinn S. (editors). Textbook of Functional Medicine. Federal Way, WA: Institute For Functional Medicine, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stafford W. “You Reading This, Be Ready” in Ask Me: 100 Essential Poems of William Stafford. Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pope Francis. Message for “Day for Life,” Vatican Press release 17 July 2013. http://www.archivioradiovaticana.va/storico/2013/07/17/pope_francis_all_life_has_inestimable_value/en1-711052. Accessed 30 October 2017.

- 41.Teilhard de Chardin P. “The Evolution of Chastity” in Toward the Future. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 1973. [Google Scholar]