See Clinical Research on Page 1258

Adoptive immunotherapy with regulatory T cells (Tregs) has the potential for treatment of autoimmune disease and as immunosuppression after solid-organ transplantation. Tregs are CD4+ T lymphocytes that express the Forkhead box p3 transcription factor. These cells dampen immune responses through a number of different potential mechanisms. Until now, the only populations of Tregs administered by adoptive transfer into humans have been without genetic manipulation and polyclonal, with some preparations enriched for donor specificity. In this issue of the KI Reports, Schreeb et al.1 propose a framework of a phase I/IIa clinical trial using Tregs that have been genetically engineered to recognize alloantigen.

The use of polyclonal versus antigen-specific Tregs is one of the most important decisions in the design of a clinical trial using Tregs to improve tolerance, either in transplantation or in autoimmune diseases. Indeed, the manufacturing process to produce polyclonal Tregs requires only expansion of a Treg pool, regardless of specificity. However, there are 2 advantages to the use of antigen-specific Tregs. First, they are more efficient as their specificity should affect their homing and proliferation abilities.2 Thus, although the exact ratio is yet to be defined in human, enrichment for donor specificity tremendously reduces the number of cells needed. To this point, the Berlin group of the ONE Study trial tracked the T cell receptor repertoire of ex vivo-sorted Tregs from patients at different time points after transplantation and compared them with the cell therapy product before injection.3 From a very diverse T cell receptor repertoire at baseline, they found significant clonal evolution within a few weeks after infusion. Clones covering >0.1% of the T cell receptor repertoire went from <15% of the total repertoire to up to 80%, suggesting the in vivo expansion of antigen-specific clones.3 Second, the use of antigen-specific Tregs could also decrease the potential risk of off-target immunosuppression, although no such signal has been recorded so far from the use of polyclonal Tregs in transplantation (reviewed in Leclerc and Lamarche4).

There are many methods to obtain antigen-specific Tregs (reviewed in Lamarche and Levings5). Previous studies in humans have relied on in vitro enrichment for graft-specific cells by expanding Tregs in the presence of donor’s antigen. This approach was used by 2 groups in the ONE Study, those from Boston and from University of California San Francisco.6 The use of those cells as adoptive immunotherapy was found to be safe, but individual reports on efficacy have not yet been published.6 Disadvantages are that it requires access to donor’s antigen, works better when there are multiple human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatches, and the cell expansion process can be quite long. Following on the revolution that happened in the cancer world with genetically engineered cells to treat cancer, treatment using chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) and transgenic T cell receptors in Tregs for tolerance is a next step forward.

CARs are engineered synthetic receptors that redirect cell specificity to recognize an antigen in an HLA-independent manner. The antigen-binding domain is extracellular and typically derived from the variable domain of the heavy and light chains of monoclonal antibodies. It is then linked to a hinge region that connects the antigen-binding domain to the transmembrane domain. The latter is often derived from natural protein, such as CD3ζ. Finally, is the intracellular signaling domain which is critical for proper T cell activation on binding to the antigen.

The use of CAR T cell therapy against malignancies has been revolutionary and led to effective and durable clinical responses. Anti–CD19 CAR T cell therapy was the first to obtain US Food and Drug Administration approval back in 2017. Since then, there has been an explosion in CAR modifications with different external domains to bind different antigenic targets and alterations in the intracellular signaling domains to increase cell persistence, efficacy, and safety.

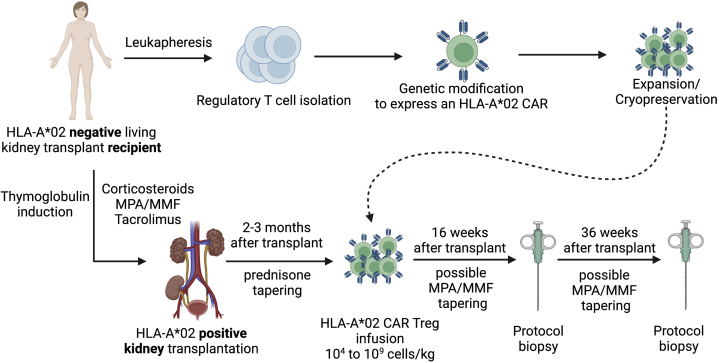

CARs have also been expressed in Tregs to promote tolerance in preclinical models of transplantation and autoimmune disease. The first antigen target tested in preclinical studies was HLA-A∗02. Tregs specific for HLA-A∗02 (A2 CAR Treg) were found to be safe and effective in the prevention of graft-versus-host disease and skin transplant rejection in mouse and humanized mouse models.7 Homing and persistence of A2-CAR Tregs were dependent on the presence of the HLA-A∗02 antigens. As approximately 50% of Caucasians express an HLA-A∗02 allele, this mismatch is present in about a quarter of the kidney transplantation in Europe and North America. The use of such CAR Tregs in preclinical mouse model of graft-versus-host disease and skin transplantation was validated by 3 independent groups (reviewed in Rosado-Sánchez and Levings7). The next step in development is now to infuse A2 CAR Tregs to promote transplant tolerance or immunosuppression minimization in HLA-A∗02–negative kidney transplant recipients receiving an HLA-A∗02–positive graft (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the proposed therapy. HLA-A∗02–negative kidney transplant recipient enrolled to receive a living HLA-A∗02–positive kidney will be recruited in the STEADFAST trial. Tregs will be isolated from the recipient before transplant and genetically modified to express an HLA-A∗02 CAR. They will then be expanded and cryopreserved. Patients will receive a thymoglobulin induction as well with corticosteroids, tacrolimus, and MPA/MMF. Prednisone will be tapered off, and MPA/MMF tapering will be attempted in patients who received the cell therapy. HLA-A∗02 CAR Tregs will be infused 2 to 3 months after transplant. Patients will have protocol biopsies 16 and 36 weeks after transplant. Created with BioRender. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPA, mycophenolic acid; Treg, regulatory T cell.

In this edition of the KI Reports, Katharina Schreeb et al.1 described the protocol of the STEADFAST study, a first-in-human phase I/IIa multicenter clinical trial using CAR Tregs. It is a multicentric European study with 5 to 6 participating renal transplant centers based in Belgium, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. They will recruit up to 21 patients with end-stage renal disease aged between 18 and 70 years. The subjects need to be HLA-A∗02 negative and designated to receive a living-donor renal transplant from an HLA-A∗02-positive donor. They will undergo leukapheresis up to 24 weeks prior surgery, and these cells will be enriched for Treg and modified to express the A2 CAR. A control cohort of up to 6 living-donor renal transplant recipients will also be recruited.

The patients will receive antithymocyte globulin (ATG) as induction therapy followed by a triple maintenance regimen consisting of corticosteroids, mycophenolic acid/mycophenolate mofetil, and tacrolimus. Prednisone will be tapered off, and mycophenolic acid/mycophenolate mofetil tapering will be attempted in patients who received the cell therapy. HLA-A∗02 CAR Tregs will be infused intravenously between 2 and 3 months after transplant. Patients will have protocol biopsies at day 0, week 16, and week 36 after kidney transplant. A total of 3 doses between 104 and 109 cells/kg body weight will be tested in single-ascending dose cohorts with 3 evaluable subjects per dose. The first and second subjects in each dose cohort will be observed for safety surveillance for a minimum of 28 and 14 days after infusion, respectively, before the next subject may be enrolled.

The protocol design is quite standard for phase I/II adoptive immunotherapy trials where there are typically 3 patients enrolled in a given dose cohort (3+3 trial). If no dose-limiting toxicity is found, the trial moves to the enrollment of the next dose. If 1 patient of 3 has a toxicity, an additional 3 are recruited at that dose. If ≥2 of 6 have developed toxicities, there is no further dose escalation. With up to 15-cell therapy-treated patients, this trial exceeds the minimal requirements. Primary end point will be safety at 28 days after infusion, and secondary end points will include additional safety parameters, clinical and renal outcome, and evaluation of biomarkers.

The STEADFAST study investigators chose to test a wide range of cell number, from 104 and 109 cells/kg body weight. The maximum dose is much higher than other studies, with an average of only 0.5 to 106 cells/kg having been tested previously.4 There is likely an even larger difference in the number of relevant Tregs being administered as previous studies used the polyclonal approach; HLA-A∗02 CAR Treg is antigen specific and therefore expected to be more effective than the previous polyclonal preparations. Considering Tregs are rare in peripheral blood, manufacturing issues might be expected for the highest doses proposed.

One important factor in the design of this study is the choice of the use of induction and timing for therapy. In the ONE Study, induction therapy was replaced by a cell therapy product, which was given between 7 days before and up to 10 days after transplant. In contrast, in the STEADFAST trial, patients from both groups will receive ATG induction, despite low immunologic risk. The presence of ATG could have several competing effects in comparison to the ONE Study protocol. If incorrectly timed, residual ATG could deplete the transferred cell product. ATG could also introduce a tolerogenic ratio of Treg-to-conventional T cell and allow delay of the cell infusion until the nadir of post-transplant decline in polyclonal endogenous Tregs after transplantation.8

The STEADFAST trial is a first in nephrology and transplantation, testing the use of genetically modified cells as therapy. It is an exciting era where we hope the revolution of treatment care will follow what happened in cancer. It is hoped that, this will lead to immunosuppression minimization or even tolerance, reducing the burden of lifelong immunosuppressive drugs.

Success of the STEADFAST study is pivotal for the future use of genetically engineered cells in nephrology and transplantation with several possible further. As cell engineering goes, the possibilities for improvement are almost endless. The target antigen could be modulated to accommodate any transplant or autoimmune glomerular diseases. The CAR’s signaling domains can be modified to improve efficacy and survival. Coexpression of constitutive or inducible factors, such as cytokines or transcription factors, with the CAR is also in development, including using the CAR T cells to deliver functional proteins at the target site (reviewed in Rosado-Sánchez and Levings7). Finally, the STEADFAST trial uses viral-mediated gene transfer to introduce the CAR in Tregs resulting in a random, variable integration. New specific DNA delivery techniques, such as CRISPR-Cas9 or zinc-finger technologies, can allow CAR insertion at a specific site into the genome and will need to be tested in Tregs. The STEADFAST study is thus the first of probably many genetically engineered cell therapy studies in transplantation.

Disclosure

CL holds 2 patent applications in the area of chimeric antigen receptor-based immunotherapy (PCT/CA2018/051167 and PCT/ CA2018/051174); one of the technologies is being tested in the STEADFAST trial. JSM has a family memmber who is employed by and has an equity interest in Genentech/Roche, serves on the SAB of Qihan, and has received honoraria and research support from Thermo Scientific/One Lambda, Inc.

References

- 1.Schreeb K., Culme-Seymour E., Ridha E., et al. Study design: Human leukocyte antigen class I molecule A∗02-chimeric antigen receptor regulatory T cells in renal transplantation. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2022.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson N.A., Lamarche C., Hoeppli R.E., et al. Systematic testing and specificity mapping of alloantigen-specific chimeric antigen receptors in regulatory T cells. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roemhild A., Otto N.M., Moll G., et al. Regulatory T cells for minimising immune suppression in kidney transplantation: phase I/IIa clinical trial. BMJ. 2020;371:m3734. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leclerc S., Lamarche C. Cellular therapies in kidney transplantation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2021;30:584–592. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamarche C., Levings M.K. Guiding regulatory T cells to the allograft. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2018;23:106–113. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawitzki B., Harden P.N., Reinke P., et al. Regulatory cell therapy in kidney transplantation (The ONE Study): a harmonised design and analysis of seven non-randomised, single-arm, phase 1/2A trials. Lancet. 2020;395:1627–1639. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30167-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosado-Sánchez I., Levings M.K. Building a CAR-Treg: going from the basic to the luxury model. Cell Immunol. 2020;358:104220. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mederacke Y.S., Vondran F.W., Kollrich S., et al. Transient increase of activated regulatory T cells early after kidney transplantation. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37218-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]