Abstract

Medicinal plants are in use of humankind since ancient and still they are playing an important role in effective and safer natural drug delivery systems. Acacia nilotica (native of Egypt) commonly known as babul belongs to family Fabaceae, widely spread in India, Sri Lanka and Sudan. Being a common and important plant, using in many ways from fodder (shoots and leaves to animals) to dyeing (leather coloration) to medicine (root, bark, leaves, flower, gum, pods). The present study is focused on investigating the natural chemistry and important biological activities of the plant. Employing bioassay guided fractionation coupled with TLC and column chromatography, a pure fraction named AN-10 was isolated from ethyl acetate fraction of crude methanol extract which identified as “Betulin (Lupan-3ß,28-diol)” by Liebermann-Burchard test and structure elucidation by UV–Vis, NMR and MS techniques. A battery of in vitro biological assays for antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer were performed and betulin showed excellent potential in all assays. It was found that the inhibitory potential in all assays were dose dependent manner and after a range of concentration, the activities get leveled off with no further increase in activity.

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Cancer, Drug discovery

Introduction

Increasing evidence from epidemiological and biological studies has shown that reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in variety of physiological and pathological processes1,2. Plant and food derived antioxidants are implicated in the prevention of cancer and aging by destroying oxidative species that initiate carcinogenesis through oxidative damage of DNA3,4. Previous scientific reports confirmed an inverse association between the daily consumption of fresh fruits & green vegetables and the chances of degenerative & chronic diseases5. The phenolic compounds of fruits and vegetable act as antioxidant through various ways, which includes complexation of redox-catalytic metal ions, scavenging of free radicals, and decomposition of peroxides. Especially in food-related systems (extracts/fractions), antioxidant activity studies using multiple experimental approaches, allow a complete screening of the putative chain-breaking capacity6. The phenols and polyphenols have attracted the interest of medical scientist because of their pharmacological properties5,7. Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. Ex Del., (family Fabaceae) is a medicinal tree known for the versatile source of bioactive components. This plant offers a variety of compounds which are potent for their spasmogenic, vasoconstrictor, anti-hypertensive, antioxidant, antispasmodic, anti-inflammatory and anti-platelet aggregatory properties8. The leaves & flowers of A. nilotica, an evergreen tree are also been used as animal fodder9–11. The bark of the plant is rich with condensed tannins, catechin, epicatechin, epigallocatechin gallate and has also been used for the treatment of viral, bacterial, amoeboid, fungal, bleeding piles & leucodermal diseases12. The previous studies performed at Genetic Toxicology Laboratory of GNDU has shown that bark of A. nilotica enriched with kaempferol, umbelliferon, gallic acid, ellagic acid, which are responsible for their potent antioxidant, antimutagenic and cytotoxic activities8,9,13. The lack of detailed & systematic phenolic profiling of A. nilotica, which might be responsible for their important biological activities, led us to design the present study. In this study, HPLC based phenolic fingerprinting, bioassay guided fractionation, isolation & identification of betulin (AN-10) from ethyl acetate fraction of crude methanol extract of A. nilotica was done. The betulin was further checked for their antioxidant activities (DPPH, Deoxyribose, Chelating power, reducing power, lipid peroxidation assays), cytotoxic (SRB assay) & anti-inflammatory activities (COX-2 inhibitory assay).

Methods

Chemicals

2’-2’ Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and Betulin (Lupan-3ß,28-diol) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and 2-deoxyribose was obtained from Lancaster Synthesis Inc. (Windham, USA). Adriamycin, 5- Fluorouracil (5-FU), Mitomycin-C, Trypsin, RPMI-1640 medium, acetic acid, trichloro acetic acid (TCA), fetal calf serum (FCS), gentamycin, penicillin, and 2-Thiobarbituric acid and HPLC authentic standards were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich USA. Human Cancer Cell lines were procured from National Cancer Research Institute, USA. Sulforhodamine B from Fluka, phosphate buffer saline (PBS) from Merck (Germany) and Tris EDTA from Hi Media. All stock solutions were prepared in double distilled H2O. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and procured from Ranbaxy Fine Chemicals Ltd. (New Delhi, India). The anti-inflammatory bioassay kit was purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Michigan, USA).

Collection and identification of plant material

The bark material of A. nilotica was collected in the month of November from a tree grown at the front side of Bebe Nanaki Girls Hostel-II, Guru Nanak Dev University (GNDU), Amritsar (As per permission and guidelines from competent authority). GNDU is located at 31.6340° N, 74.8259° E with loamy soil texture. Plant identification was conducted at the herbarium in the Department of Botanical & Environmental Sciences, GNDU, Amritsar–India, where a voucher specimen of A. nilotica is deposited (A/C # 6421, dated 12-01-2007). All plant experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of institution.

Sample preparation and extraction

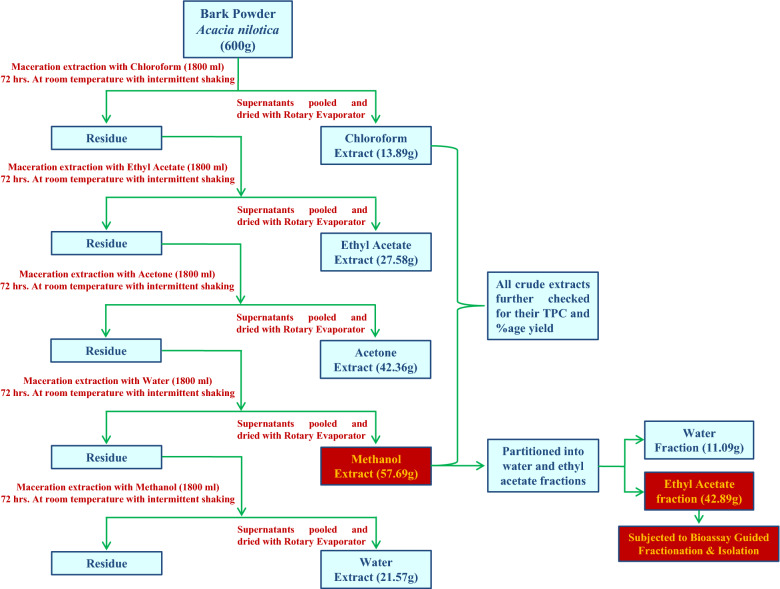

The bark material was washed with tap water (thrice) to remove dust particles, dried in oven at 40 °C for 24 h and grounded to fine powder. The fine bark powdered material (600 g) of A. nilotica was macerated first with chloroform (1800 ml) for 72 h with intermittent vigorous shaking and after every 24 h supernatant was filtered, and the dried powder was re-macerated twice with fresh chloroform solvent. Then all supernatants pooled and dried by using a rotary evaporator (BUCHI R-300, SWITZERLAND). The crude methanol extract, which was used in present study, was obtained after maceration extracting the bark powder in chloroform, ethyl acetate and acetone. i.e. increasing order of solvent polarity. The methanol extract was further fractioned into water and ethyl acetate fractions (Fig. 1). The dried crude extracts were transferred into vials and kept in a desiccator until use.

Figure 1.

Extraction/fraction procedure of Methanol and other crude extracts from bark powder of Acacia nilotica.

Determination of total phenolic content

The Total Phenolic Content (TPC) of different crude extracts of A. nilotica was determined by the method of Folin Ciocalteu14 as gallic acid equivalent (GAE) in milligram per gram extract sample.

HPLC analysis of ethyl acetate fraction of methanol extract

Standard stock solution of gallic acid, quercetin, myricetin, rutin, quercetin, kaempferol, catechin, epicatechin, ferulic acid and 7-hydroxycoumarin were prepared as 1 mg/1 ml in HPLC grade methanol: water (90:10). HPLC analysis was performed on a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC system and Shimadzu LC solution (ver. 1.21 SP1) software. Chromatography was carried out on a Luna C18 (2) column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size). At a column temperature of 27 °C and a flow rate of 0.80 mL/min using solvent A (water) and solvent B (0.02% trifluroacetic acid (TFA) in acetonitrile) with a linear gradient elution: 70% A (5 min), 15–35% (7 min), 35–45% (11 min), 45–35% (16 min), 35–15% (20 min) at λ 280 nm. Stock solution containing ten analytes were prepared and diluted to appropriate concentrations for establishing calibration curves and different concentrations of theses analytes were injected thrice for the quantitative analysis and the calibration curves were constructed by plotting the peak areas versus the concentration of each analyte. The selectivity of the method was determined by analyzing standards and methanol extract. The peaks of reference compounds were identified by comparing their retention times (rt in min.) with the spectrum of authentic standard (Sigma Aldrich, USA).

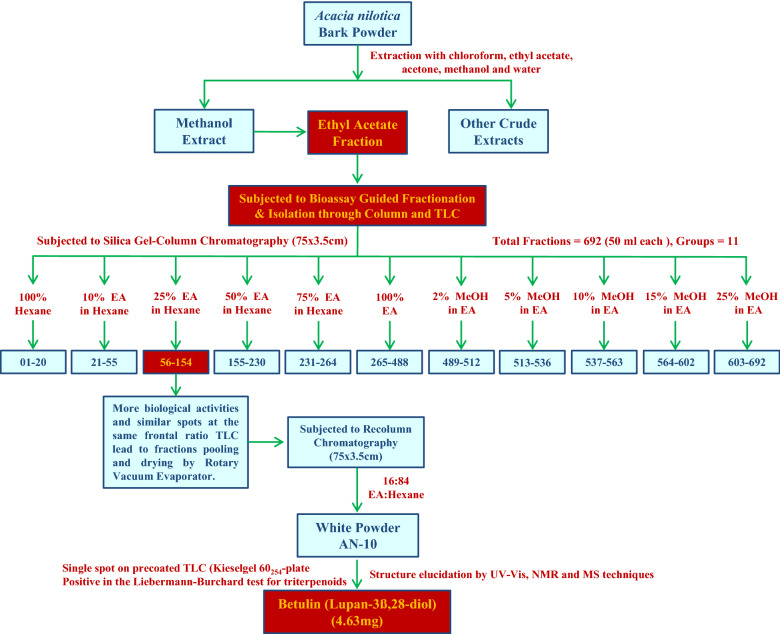

Bioassay guided fractionation and isolation of triterpenoids

In the process of bioassay-guided fractionation, ethyl acetate fraction of crude methanol extract is first tested for their activities, then fractionation and separation through column and TLC and then the resulting fractions are again tested for activity. The most active fractions (#56–154) with similar spot on pre-coated TLC plates is processed further for the separation of triterpenoids by column chromatography (data shown in results section).

20 g ethyl acetate fraction of methanol extract mixed with celite ‘545’ was suspended in methanol and subjected to column chromatography using a 75 × 3.5 cm glass column filled with acidic alumina (brockman’s activity) upto 5 cm down from the top of glass column. After bedding down the silica gel, column elution stated with 100% hexane and then conducted by successive applications of solvent gradients of hexane/ethyl acetate 90;10, 75:25, 50:50, 25:75, 0:100 then with solvent gradient of methanol/ethyl acetate 2:98, 5:95, 10:90, 15:85, 20:80 to collect total of 692 fractions (50 ml each). Preliminary thin layer chromatography of all total 692 fractions was done to check number of compounds in each elution (based on rf values and no. of spots). Elutions showing same spots on TLC plates were pooled, concentrated and dried with Rotary evaporator to obtain high purity fractions. Fractions numbering 56–154 eluted ethyl acetate/hexane 25:75 showed single spot (same rf value) on pre-coated TLC plates lead to pooling and drying of fractions. The pooled and dried fractions were re-chromatographed with solvent gradient of ethyl acetate/hexane and fraction named “AN-10” eluted with 16;84 (ethyl acetate:hexane) resulted in isolation of a white 4.63 mg amorphous powder (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Bioassay guided fractionation and isolation of triterpenoids from ethyl acetate fraction of methanol extract of Acacia nilotica bark powder.

Identification of AN-10 fraction by NMR and MS techniques

1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded for purified “AN-10” fraction at 300 MHz, using 5-mm sample tubes on a Bruker Avance-300 spectrometer. CD3OD was used as solvent for measurements at 30 °C. For structure elucidation and complete spectrum analysis, other additional experiments were performed as necessary: DEPT, 13C observation with selective 1H decoupling, 2D H,H-COSY. 13C chemical shifts δ are reported in ppm relative to TMS with an internal reference. With very few exceptions all NMR assignments are unequivocal. Mass spectra were recorded on QTOF-Micro of water Micromass. Melting point was determined on a Barnstead Electrothermal 9100.

Antioxidant activities testing assays

In vitro antioxidant activities (AOA) of the crude extracts/fractions of A. nilotica and “AN-10” fraction was addressed by employing DPPH scavenging assay measured in terms of hydrogen using the stable nitrogen centered radical DPPH following the method of Blois15. The hydroxyl radical scavenging was checked with site specific and non-site specific deoxyribose degradation method of Halliwell et al.16 and Arouma et al.17. The reducing power was determined as described by Oyaizu18. The chelating effect on ferrous ions was determined according to the method of Dinis et al.19 and Lipid Peroxidation (LPO) was determined according to Halliwell & Guttridge20.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

The Sulforhodamine B dye assay was used for In vitro cytotoxic screening of crude extracts/fractions of A. nilotica and “AN-10” fraction according to Skehan et al.21. For primary screening, A-549 (Lung), DU-145 & PC-3 (prostate), IGROV-1 (Ovary) and MCF-7 (Breast) cancer cell lines were used. The treatments were (OD) was recorded at 540 nm, on ELISA reader and percent growth inhibition in the presence of extract/fraction and “AN-10” was calculated.

Anti-inflammatory activity

In vitro COX-2 inhibiting activities of crude extracts/fractions of A. nilotica and “AN-10” fraction has been evaluated using ‘COX (ovine) inhibitor screening assay’ kit with 96-well plates. Both ovine COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes were included22. This screening assay directly measures PGF2α produced by SnCl2 reduction of COX-derived PGH2. The wells of the 96-well plate showing low absorption at 405 nm indicate the low level of prostaglandins in these wells and hence the less activity of the enzyme. Therefore, the COX inhibitory activities of the crude extracts/fractions of A. nilotica and “AN-10” fraction could be quantified from the absorption values of different wells the 96-well plate.

Statistical analysis

All experimental analyses were performed in triplicate (n = 3) and the data was presented as mean ± SD on excel sheet. For in vitro antioxidant assays, one way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s test (P < 0.05) was used to analyze the differences among IC50 of various AN-10 and extract/fractions for different antioxidant assays.

Results

% yield of extract, TPC and bioassay guided fractionation

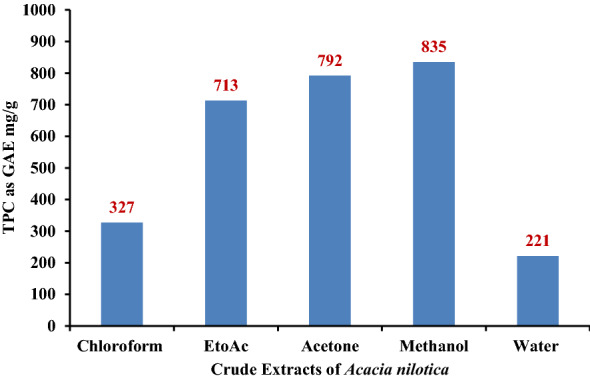

The high % yield (57.69 g and 6.15% yield) and Total Phenolic Content (835 mg/g as GAE) of methanol extract than other crude extracts of A nilotica lead for the detailed bioassay-guided fractionation (Fig. 3), HPLC based phytochemical screening and biological activities. Silica-gel column chromatography was performed on ethyl acetate fraction (42.89 g) of methanol extract of A. nilotica and 692 fractions of 50 ml each were collected. All these fractions were pooled into 11 groups according to their similar spot at the same frontal ratio on thin layer chromatography profiles and biological activities (Fig. 1). 54–156 fractions (group 3) exhibited high antioxidant, anti-inflammatory & anticancer activities as compared to other fractions and group of fractions (Table 1). In order for the detailed chemical investigation and identification of active compounds, the most active fractions (group-3) were pooled, dried and fractionated through re-column chromatography (silica gel, 75 × 3.5 cm) and “AN-10” fraction was collected by solvent gradient of ethyl acetate/hexane (16:84). Other chromatography and spectroscopy techniques were used for identification and structure establishment of “AN-10” fraction.

Figure 3.

Total Phenolic Content of different crude extracts from bark of Acacia nilotica in mg/g as GAE (Gallic acid equivalent).

Table 1.

Bioassay guided fractionation based biological activities of fractions collected from methanol extract of Acacia nilotica through column chromatography.

| Group | Fraction numbers (50 ml each) |

In vitro bioactivity testing assays | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | Deoxyribose Degradation |

Reducing power | Chelating power | Lipid peroxidation | COX | Cancer | |||

| SS | NSS | ||||||||

| Group -1 | 01–20 | + + | + + | + + | + | + + | + + + | + + | + + + |

| Group -2 | 21–55 | + + + | + + | + + | + + | + + | + + + | + + | + + |

| Group -3 | 56–154 | + + + + | + + + + | + + + | + + + + | + + + | + + + + | + + + + | + + + + |

| Group -4 | 155–230 | + + | + | + + | + + + | + + | + + + | + + | + + + + |

| Group -5 | 231–264 | + + | + + | + | + + | + + | + + | + + + + | + + |

| Group -6 | 265–488 | + + + | + + + | + + | + + + | + + + + | + + + | + + + | + + + |

| Group -7 | 489–512 | + + + | + + | + + + | + + | + + | + + + | + + | + + + |

| Group -8 | 513–536 | + + + + | + + + | + + | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + + + | + + + |

| Group -9 | 537–563 | + + + + | + + + | + + | + + + | + + + | + + | + + + | + + + + |

| Group -10 | 564–602 | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + | + + | + + + | + + + | + + + |

| Group -11 | 603–692 | + + + | + + | + + | + + | + | + | + + | + + |

SS: Deoxyribose Site specific assay; NSS: Deoxyribose non-site specific assay.

Activity percentage (%) range: + : 0–25%, + + : 25–50%, + + + : 50–75%, + + + + : 75–100%.

In HPLC analysis, for the better resolution, different mobile phases were used and after several trails, mobile phase consisting of solvent A (water) and solvent B (0.02% trifluroacetic acid (TFA) in acetonitrile) as a solvent gradient was finely selected in order to achieve optimal separation & quantification, high sensitivity, and good peak shape. Table 2 shows the Retention Time (RT in minutes) and % quantification as µg/mg of 10 major polyphenols.

Table 2.

HPLC based phenolic fingerprinting and quantification of the major polyphenols in ethyl acetate fraction of crude methanol extract of Acacia nilotica.

| Compound | RT (min) | Quantification (μg/mg) | Molecular formula | Molecular mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | 3.57 | 156.26 | C7H6O5 | 170.12 |

| Catechin | 4.83 | 265.19 | C15H14O | 290.27 |

| Epicatechin | 5.61 | 196.35 | C15H14O | 290.27 |

| Rutin | 7.10 | 109.78 | C27H30O16 | 610.52 |

| Umbelliferone | 9.24 | 183.17 | C9H6O3 | 162.14 |

| o-Coumaric | 10.68 | t | C9H8O3 | 164.16 |

| Quercetin | 12.95 | 161.91 | C15H10O7 | 302.24 |

| Myricetin | 11.09 | 117.29 | C15H10O8 | 318.24 |

| Betulin | 15.42 | 56.83 | C30H50O2 | 442.72 |

| Kaempferol | 16.10 | 19.27 | C15H10O6 | 286.24 |

RT: Retention Time.

“t” indicates “trace”.

The presence of these polyphenols, in methanol extract of A. nilotica, was confirmed by comparison of their retention times and overlaying of UV spectra with authentic standards. The methanol extract which showed presence of these 10 polyphenols, among which catechin, epicatechin, quercetin gallic acid, umbelliferone, rutin and myricetin quantitatively found in considerable amount while Kaempferol & betulin were found present in traces amount whereas o-Coumaric was not detected. Many unknown peaks were also observed in the chromatogram which was characterized as the glycosides of flavonols.

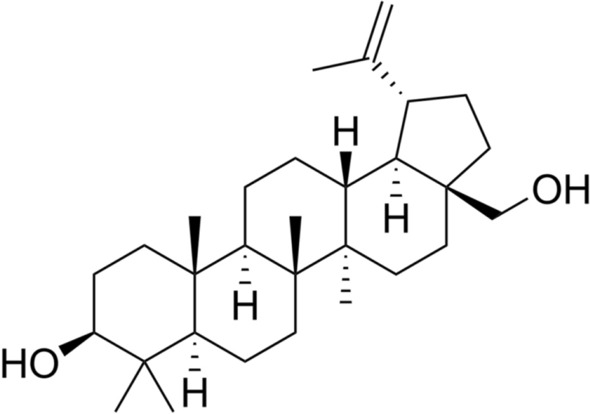

Identification and structure elucidation of “AN-10” fraction

The results of the present study showed that the methanol extract of A. nilotica contains a complex mixture of polyphenols consisting mainly of polyhydroxyflavan-3-ols (catechins, epicatechin) and ellagic acid derivatives. The chromatographic purification of this extract resulted in the isolation of compound AN-10 (4.63 mg). These results provided unequivocal determination of structures and stereochemistry. The key evidence and arguments used to define the structures shown are briefly described. Fraction “AN-10” isolated as a white amorphous powder which were positive in the Liebermann-Burchard test for triterpenoids. Its positive ion HRESI-QTOF-MS displayed protonated molecular ion peak [M+H]+ at m/z 443 corresponded to the molecular formula C30H50O2. The 1H NMR spectrum of AN-10 indicated the presence of six methyl groups at H 0.76 (s, H3-24), 0.82 (s, H3-25), 0.97 (s, H3-23 and H3-27), 1.02 (s, H3-26), 1.68 (s, H3-30) together with two diastereotopic protons for a methylene group attached to hydroxyl at H 3.31 and 3.78 (d, J = 10.7, H28 and H-28') and two exocyclic methylene protons at H 4.58, 4.68 (s, H-29 and 29') established lupane skeleton for compound23. 13C NMR spectrum displayed signals due to six methyl carbons at C 14.9, 15.5, 16.1, 16.2, 19.2 and 28.1, oxygen-bearing methine and methylene carbons at C 79.1 and 60.7 and a set of exocyclic olefinic carbons at C 109.6 and 150.6. The 1H and 13C NMR signals for exocyclic double bond suggested the presence of an isopropenyl moiety. Therefore, on the basis of NMR (1H, 13C, DEPT, HMQC and HMBC) and mass spectral data and comparison with those reported in the literatures and the structure of the compound was identified as Betulin (Lupan-3β,28-diol) having molecular formula C30H50O2, Molecular weight of 442.72 and melting point of 251.624. (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of AN-10 fraction (C30H50O2).

Biological activities of betulin

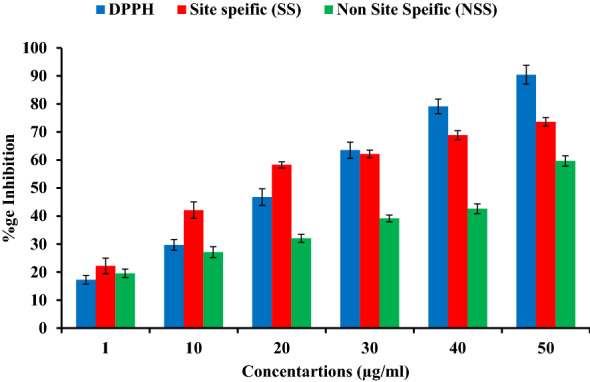

Figure 5 depicts the positive dose dependent DPPH radical scavenging potential of betulin. The addition of betulin led to change in colour, with a very fast reaction speed up to a concentration of 50 µg/ml. At 50 µg/ml concentration betulin exhibited 88.67% of activity (IC50 23.75 µg/ml), and there is no change in colour and inhibition potential after this concentration. These in-vitro DPPH radical scavenging potential of Betulin revealed remarkable antioxidant potential. Previous studies reported the antioxidant activity of plant extracts has a positive correlation with percentage radical scavenging activity25. Therefore, an extract with high percentage radical scavenging activity ought to be a potent antioxidant in vitro and in vivo. The high percentage radical scavenging activity translates to low EC50/IC50 values26.

Figure 5.

In vitro DPPH and hydroxyl radical scavenging potential of “Betulin” by site and non-site specific deoxyribose degradation assay.

Betulin also exhibited very good site (72.83%) & non-site (58.44%) specific hydroxyl radical scavenging potential at 50 µg/ml concentration and the results also showed that there is slight difference in the antioxidant potential of betulin in the site & non site specific modes of deoxyribose degradation assays.

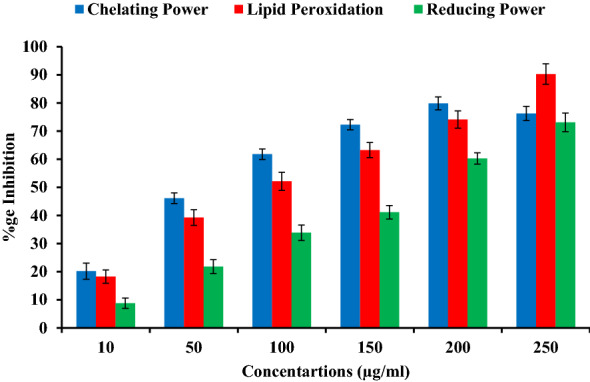

In chelating power assay, betulin isolated from A. nilotica interfered with the formation of ferrous and ferrozine complexes, and have good chelating activity of 75.22% (IC50 58.24 µg/ml) at 250 µg/ml concentration and are able to capture ferrous ion before ferrozine (Fig. 5).

Figure 6 also showed the dose response ability of the betulin to reduce Fe(III) to Fe(II) at different concentrations. This reduction helps to predict the betulin ability to mimic the body’s endogenous antioxidants like bilirubin and uric acid in attenuating oxidative stress27,28. Therefore, high ferric reducing antioxidant power is correlated with increase in absorbance values and low IC50 values. Our results are confirmatory with previous reports which found that catechin, (epi) gallocatechin and caffeic acid present in the stem bark crude extract of S. crude have good antioxidant activities against DPPH radical scavenging and reducing power activities with low IC50 values29.

Figure 6.

In vitro chelating power, reducing power and lipid peroxidation inhibition of “Betulin” through chelating reducing and Lipid peroxidation assays.

In lipid peroxidation assay, the betulin exhibit moderate to strong antioxidant potential i.e. 16.25–90.1567.2 ± 1.8% at 10–250 µg /ml concentration (weak–good). All the values of antioxidant activities were considered to be significant at P ≤ 0.05.

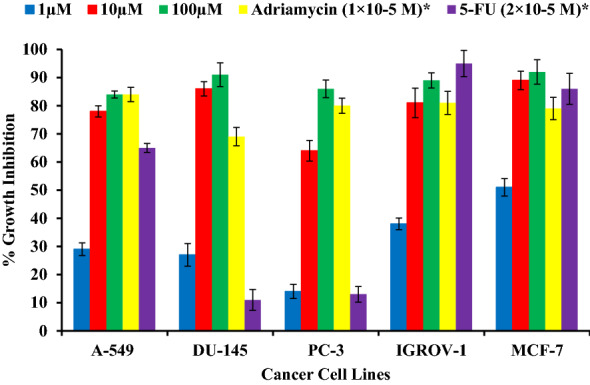

In this research work, cytotoxic activities of Betulin toward the A-549, DU-145, PC-3, IGROV-1 & MCF-7 cell lines was determined and the growth inhibition percentage by betulin is shown in Table 3 and Fig. 7. Betulin exhibited excellent potent anticarcinogenic potential at different concentrations. At 100 μM concentration, betulin exhibits 84% (A-549), 91% (DU-145), 86% (PC-3), 89% (IGROV-1) & 92% (MCF-7). Positive controls showed 84, 69, 80, 81, 79 (Adriamycin) 65, 11, 13, 95, 86 (5-FU) for A-549, DU-145, PC-3, IGROV-1 & MCF-7 cell lines at 1 × 10–5 M 2 × 10–5 M concentrations respectively.

Table 3.

In vitro cytotoxicity activities of betulin against different human cell lines.

| Compound | Concentration | A-549 (Lung) | DU-145 (Prostate) | PC-3 (Prostate) | IGROV-1 (Ovary) | MCF-7 (Breast) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betulin | 1 µM | 29 | 27 | 14 | 38 | 51 |

| 10 µM | 78 | 86 | 64 | 81 | 89 | |

| 100 µM | 84 | 91 | 86 | 89 | 92 | |

| Adriamycin | 1 × 10–5 M | 84 | 69 | 80 | 81 | 79 |

| 5-FU | 2 × 10–5 M | 65 | 11 | 13 | 95 | 86 |

Figure 7.

In vitro growth inhibition potential of “Betulin” against different human lung, prostate, ovary and breast cancer cell lines.

Betulin isolated from A. nilotica was also found to be a selective inhibitor of COX-2 (COX-2 selectivity > 10). At a concentration of 10 μM, it inhibited the COX-1 by 43.81% whereas COX-2 was inhibited by 95.03% (Table 4). The ethyl acetate fraction of methanol extract also demonstrate strong capacity to suppress this inflammatory pathway. In the presence of betulin, the level of PGE2 dropped too low. Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds are known to target cyclooxigenase-mediated inflammation30–32 HPLC based presence of polyphenols and these polyphenols already reported to block cyclooxygenase activity induced by UVB radiation. Thus it might also be implicated in suppression of cyclooxygenase-mediated inflammatory pathway33.

Table 4.

Cyclooxygenase enzyme mediated anti-inflammatory activities (COX-1 & COX-2) of “Betulin “isolated from bark of Acacia nilotica.

| Compound | % Inhibition | IC50 (µM) | COX-2 selectivity* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COX-2 | COX-1 | COX-2 | COX-1 | |||

| 1 µM | 10 µM | 10 µM | ||||

| Betulin | 56.22 | 95.03 | 43.81 | < 1.0 | > 10 | > 10 |

| Rofecoxib** | 75 | 100 | 75 | 0.3 | 40 | ˜133 |

| Celecoxib ** | 50 | 100 | 65 | 1.2 | 14 | ˜10 |

*COX-2 selectivity = IC50 (COX-1)/ IC50 (COX-2).

**Reported in literature (Kaur et al., 2009)22.

Discussion

In the past two decades triterpenes have attracted attention because of their pharmacological potential. Among them, betulin is the most abundant and it is a representative compound of Betula platyphylla, a tree species belonging to the Betulaceae family34. Betulin has been demonstrated to have a selective cytotoxicity in tumor cell line35–37. It has also shown a strong reduction of hepatotoxicity38. Furthermore, betulin was shown to exhibit chemopreventive effects on UV induced DNA damage in congenital naevi (CMN) cells39. Previous studies on betulin also shown protective effects against Cd-induced cytotoxicity occur via the anti-apoptosis pathway in Hep3B cells, ethanol induced cytotoxicity in HepG2 and potent superoxide anion generation inhibitors in human neutrophils40–42. The antioxidant property of betulin was confirmed by its ability to scavenge and prevent the attack of free radicals on the membranes by increasing its negative surface charge43. Betulin and betulinic acid have been shown as potent phospholipase A2 inhibitors44. Furthermore, betulin acts as a modest TNF-α inducer by enhancing mitogen-induced TNF-α production, and betulinic acid modulates cytokine production by Th1/Th2 cell subpopulations45. In the present study, we have isolated betulin from ethyl acetate fraction of methanol extract of A. nilotica and checked their different antioxidant, cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory activities employing a battery of in vitro assays. It is important to use different assays, instead of relying on a single assay to assess and compare the antioxidant capacity.

The methanol extract showed high biological potential than the other crude extracts of the A. nilotica (data not shown) and these results suggested that these high biological activities might be due to the high TPC. Many previous studies observed the direct relationship between TPC and antioxidant activity in medicinal plant extracts. The phenolic compounds may contribute directly to antioxidative action or as free radical scavengers due to their hydroxyl groups46. Tanaka et al.47, reported that 1 g phenolic compounds daily from a diet rich in fruits and vegetables have inhibitory effects on mutagenesis and carcinogenesis in humans. Currently the interests of phenolic compounds are increasing in the food industry because they retard oxidative degradation of lipids and thereby improve the quality and nutritional value of food48.

The HPLC based phenolic fingerprinting of methanol extract of A. nilotica showed the presence of many phenolic components such as gallic acid, quercetin, myricetin, rutin, kaempferol, catechin, epicatechin, ferulic acid, betulin and umbelliferone and are very significant to understand the relationship between the phenolic composition and bioactivities. The enrichment of the extract with polyphenols might responsible for the potent biological activities of the extract. Several previous studies have reported that these polyphenols exhibited strong antioxidative, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory activities49–52.

The methanol extract of A. nilotica showed the highest amount of TPC (835 mg/g as GAE) which lead us for the chromatographic & spectroscopic analysis of methanol extract. The chromatographic analysis on precoated Kieselgel 60254 plate (0.2 mm thick; Merck, India), showed many spots of UV & iodine sensitive compounds. The repeated column chromatography of the fraction 54–156 (group 3) as shown in Fig. 2, resulted in the isolation of white amorphous powder which was positive in the Liebermann-Burchard test for triterpenoids (M+H]+ at m/z 443 & molecular formula C30H50O2). The NMR, Mass spectroscopy techniques and previous reports established the chemical structure of compound as Betulin (Lupan-3ß,28-diol)24.

In results of the present study we found that betulin was effective for reducing the stable DPPH radical to the yellow colored diphenylpicryl hydrazine, indicating their DPPH radical scavenging potential. The higher DPPH radical scavenging potential and lower IC50 values are inverse to each other. It is pertinent to mention here that, DPPH potential may be due to the hydrogen atom donating ability of betulin, which further help in trapping free radicals. EDTA is used as the metal chelator in chelating power assay as it is a strong metal chelator. In the present study, betulin exhibits good reducing potential (Fig. 6). Natural plants/extracts having chelating potential are believed to inhibit lipid peroxidation by stabilizing transition metals53. In reducing power assay, the yellow colour of the test solution changes to various shades of green and blue based upon the reducing power of the tested compound. The reductive ability assay suggests that the betulin is able to donate electron, hence they should be able to donate electrons to free radicals in actual biological or food systems, making the radicals stable and unreactive. Reducing power is one mechanism of action of antioxidants and may serve as a significant indicator of potential antioxidant activity54. Previous reports also found dose dependent manner of hydroxyl radicals scavenging potential of xylose and lysine Maillard reaction products55. The free radical scavenging capability of phenolics are closely related with structural formation, molecular weight and presence of aromatic rings & hydroxyl groups of the phenolics56.

Recent reports found that betulin to be active against colorectal, breast, prostate & lung cancer cell lines57,58. Betulin is a natural compound, which contains derivatives that have been shown to possess strong anti-tumor properties5,59. Recent studies also found that betulin in combination with cholesterol, is a very potent agent in killing cancer cells in vitro60.

Inflammation is a complex process, which involves many cell signaling pathways in addition to free radical production which are responsible for tissue degeneration and many diseases viz. rheumatoid arthritis, arteriosclerosis, myocarditis, infections, cancer, metabolic disorders61–63. COX-2 is an enzyme which is necessary for the production of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and thus has been a target for many present anti-inflammatory and cancer-preventive drugs64. Several natural products of plant origin have been shown to transmit their anti-inflammatory activities through suppression of COX-265–67.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a senior research fellowship awarded by university grants commission (UGC), New Delhi, India to RS. Authors are thankful Dr. Tarunpreet Singh Thind for in-vitro anticarcinogenic experimentation.

Author contributions

R.S. did experimental work and paper writing. P.K. completed experimental work, data analysis and paper writing. S.A. Conceived idea and paper writing.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abenavoli L, Greco M, Milic N, Accattato F, Foti D, Gulletta E, Luzza F. Effect of mediterranean diet and antioxidant formulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized study. Nutrients. 2017;9:870. doi: 10.3390/nu9080870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olugbami JO, Damoiseaux R, France B, Onibiyo EM, Gbadegesin MA, Sharma S, Gimzewski JK, Odunola OA. A comparative assessment of antiproliferative properties of resveratrol and ethanol leaf extract of Anogeissusleiocarpus (DC) Guill and Perr against HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017;17:381–386. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1873-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czerwonka A, Kawka K, Cykier K, Lemieszek MK, Rzeski W. Evaluation of anticancer activity of water and juice extracts of young Hordeum vulgare in human cancer cell lines HT-29 and A549. Ann. Agr. Env. Med. 2017;24:345–349. doi: 10.26444/aaem/74714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dekant W, Fujii K, Shibata E, Morita O, Shimotoyodome A. Safety assessment of green tea based beverages and dried green tea extracts as nutritional supplements. Toxicol. Lett. 2017;277:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stirpe M, Palermo V, Bianchi MM, Silvestri R, Falcone C, Tenore G, Novellino E, Mazzoni C. Annurca apple (M. pumila Miller cv Annurca) extracts act against stress and ageing in S. cerevisiae yeast cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017;17:200–209. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1666-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mello LD, Kubota LT. Biosensors as a tool for the antioxidant status evaluation. Talanta. 2007;72:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MfotieNjoya E, Munvera AM, Mkounga P, Nkengfack AE, McGaw LJ. Phytochemical analysis with free radical scavenging, nitric oxide inhibition and antiproliferative activity of Sarcocephaluspobeguinii extracts. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017;17:199–208. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1712-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh BN, Singh BR, Sarma BK, Singh HB. Potential chemoprevention of N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis by polyphenolics from Acacia nilotica bark. Chem-Biol. Interact. 2009;181:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh R, Singh B, Singh S, Kumar N, Kumar S, Arora S. Anti-free radical activities of kaempferol isolated from Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. Ex. Del. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2008;22:1965–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh R, Singh B, Singh S, Kumar N, Kumar S, Arora S. Umbelliferone–An antioxidant isolated from Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. Ex. Del. Food Chem. 2010;120:825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sultana B, Anwar F, Przybylski R. Antioxidant activity of phenolic components present in barks of Azadirachta indica, Terminalia arjuna, Acacia nilotica, and Eugenia jambolana Lam. trees. Food Chem. 2007;104:1106–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhargava A, Srivastava A, Kumbhare VC. Antifungal activity of polyphenolic complex of Acacia nilotica bark. Indian Forests. 1998;124:292–298. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaur K, Micheal M, Arora S, Harkonen P, Kumar S. In vitro bioactivity guided fractionation and characterization of polyphenolic inhibitory fractions from Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. Ex. Del. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kujala TS, Loponen JM, Klika KD, Pihlaja K. Phenolic and betacyanins in red beetroot (Beta vulgaris) root: Distribution and effects of cold storage on the content of total phenolics and three individual compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:5338–5342. doi: 10.1021/jf000523q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blois MS. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;26:1199–1200. doi: 10.1038/1811199a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC, Aruoma OI. The deoxyribose method: A simple test-tube assay for determination of rate constants for reaction of hydroxyl groups. Anal. Biochem. 1987;165(215):219. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arouma OI, Grootveld M, Halliwell B. The role of iron in ascorbate dependent deoxyribose degradation. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1987;29:289–299. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(87)80035-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oyaizu M. Studies on product of browning reaction prepared from glucose amine. Jpn. J. Nutr. 1986;44:307–315. doi: 10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.44.307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinis TCP, Madeira VMC, Almeida LM. Action of phenolic derivates (acetoaminophen, salicylate, and 5-aminosalicylate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994;315:161–169. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halliwell B, Guttridge JMC. In Free radicals in biology and medicine. 2. Japan Scientific Societies Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skehan P, Storeng R, Scudiero D, Monks A, McMahon J, Vistica D, Warren JT, Bokesch H, Kenney S, Boyd MR. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1107–1112. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaur P, Kaur S, Kumar S, Singh P. Rubia cordifolia L. and Glycyrrhiza glabra L. medicinal plants as potential source of COX-2 inhibitors. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010;2:108–120. doi: 10.5099/aj100200108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahato SB, Kundu AP. 13C NMR spectra of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids—a compilation and some salient features. Phytochem. 1994;37:1517–1575. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)89569-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayatollahi SA, Shojaii A, Kobarfard F, Noori M, Fathi M, Choudhari MI. Terpens from aerial parts of Euphorbia splendida. J. Med. Plant Res. 2009;3:660–665. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fidrianny I, Budiana W, Ruslan K. Antioxidant activities of various extracts from Ardisia sp. leaves using DPPH and CUPRAC assays and correlation with total flavonoid, phenolic, carotenoid content. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2015;7:859–865. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ngai ND, Moriasi G, Ngugi MP, Njagi JM. In vitro antioxidant activity of dichloromethane: methanolic leaf and stem extracts of Pappea capensis. World J. Pharm. Res. 2019;8:195–211. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qader SW, Abdulla MA, Chua LS, Najim N, Zain MM, Hamdan S. Antioxidant, total phenolic content and cytotoxicity evaluation of selected Malaysian plants. Molecules. 2011;16:3433–3443. doi: 10.3390/molecules16043433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh V, Kahol A, Singh IP, Saraf I, Shri R. Evaluation of antiamnesic effect of extracts of selected Ocimum species using in-vitro and in-vivo models. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;193:490–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grzesik M, Naparło K, Bartosz G, Sadowska-Bartosz I. Antioxidant properties of catechins: Comparison with other antioxidants. Food Chem. 2018;241:480–492. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ambriz-Perez DL, Leyva-Lopez N, Gutierrez-Grijalva EP, Heredia JB. Phenolic compounds: Natural alternative in inflammation treatment. A review. Cogent. Food Agric. 2016;2:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 31.López-Posadas R, Ballester I, Mascaraque C, Suárez MD, Zarzuelo A, Martínez-Augustin O, Sánchez de Medina F. Flavonoids exert distinct modulatory actions on cyclooxygenase 2 and NF-kappaB in an intestinal epithelial cell line (IEC18) Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160:1714–1726. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tungmunnithum D, Thongboonyou A, Pholboon A, Yangsabai A. Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds from medicinal plants for pharmaceutical and medical aspects: An overview. Medicines. 2018;93:1–16. doi: 10.3390/medicines5030093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang NJ, Lee KW, Shin BJ, Jung SK, Hwang MK, Bode AM, Heo YS, Lee HJ, Dong Z. Caffeic acid, a phenolic phytochemical in coffee, directly inhibits Fyn kinase activity and UVB-induced COX-2 expression. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:321–330. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alakurtti S, Makela T, Koskimies S, Yli-Kauhaluoma J. Pharmacological properties of the ubiquitous natural product betulin. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006;29:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fulda S, Susin SA, Kroemer G, Debatin KM. Molecular ordering of apoptosis induced by anticancer drugs in neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4453–4460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu WK, Ho JC, Cheung FW, Liu BP, Ye WC, Che CT. Apoptotic activity of betulinic acid derivatives on murine melanoma B16 cell line. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004;498:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt ML, Kuzmanoff KL, Ling-Indeck L, Pezzuto JM. Betulinic acid induces apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cell lines. Eur. J. Cancer. 1997;33:2007–2010. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miura N, Matsumoto Y, Miyairi S, Nishiyama S, Naganuma A. Protective effects of triterpene compounds against the cytotoxicity of cadmium in HepG2 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:1324–1328. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salti GI, Kichina JV, Das Gupta TK, Uddin S, Bratescu L, Pezzuto JM, Mehta RG, Constantinou AI. Betulinic acid reduces ultraviolet-C-induced DNA breakage in congenital melanocytic naeval cells: evidence for a potential role as a chemopreventive agent. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:99–104. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200104000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oh SH, Choi JE, Lim SC. Protection of betulin against cadmium-induced apoptosis in hepatoma cells. Toxicology. 2006;220:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamashita K, Lu H, Lu J, Chen G, Yokoyama T, Sagara Y, Manabe M, Kodama H. Effect of three triterpenoids, lupeol, betulin, and betulinic acid on the stimulus-induced superoxide generation and tyrosyl phosphorylation of proteins in human neutrophils. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2002;325:91–96. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(02)00252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szuster-Ciesielska A, Kandefer-Szerszen M. Protective effects of betulin and betulinic acid against ethanol-induced cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells. Pharmacol. Rep. 2005;57:588–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vidya L, Malini MM, Varalakshmi P. Effect of pentacyclic triterpenes on oxalate-induced changes in rat erythrocytes. Pharmacol. Res. 2000;42:313–316. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernard P, Scior T, Didier B, Hibert M, Berthon JY. Ethnopharmacology and bioinformatic combination for leads discovery: application to phospholipase A(2) inhibitors. Phytochemistry. 2001;58:865–874. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zdzisinska B, Rzeski W, Paduch R, Szuster-Ciesielska A, Kaczor J, Wejksza K, Kandefer-Szerszen M. Differential effect of betulin and betulinic acid on cytokine production in human whole blood cell cultures. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2003;55:235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hatano T, Edamatsu R, Hiramatsu M, Mori A, Fujita Y. Effects of the interaction of tannins with co-existing substances. VI: effects of tannins and related polyphenols on superoxide anion radical and on 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1989;37:2016–2021. doi: 10.1248/cpb.37.2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka M, Kuei CW, Nagashima Y, Taguchi T. Application of antioxidativemailrad reaction products from histidine and glucose to sardine products. Nippon Suisan Gakk. 1998;54:1409–1414. doi: 10.2331/suisan.54.1409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aneta W, Jan O, Renata C. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem. 2007;105:940–949. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pendota SC, Aremu AO, Slavtínská LP, Rárová L, Grúz J, Doležal K, Van Staden J. Identification and characterization of potential bioactive compounds from the leaves of Leucosideasericea. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;220:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheleva-Dimitrova D, Zengin G, Balabanova V, Voynikov Y, Lozanov V, Lazarova I, Gevrenova R. Chemical characterization with in vitro biological activities of Gypsophila species. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018;21:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmad M, Malik K, Tariq A, Zhang G, Yaseen G, Rashid N, Sultana S, Zafar M, Ullah K, Khan MPZ. Botany, ethnomedicines, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Himalayan Paeony (Paeonia emodi Royle) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;220:197–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bagheri E, Hajiaghaalipour F, Nyamathulla S, Salehen N. The apoptotic effects of Bruceajavanica fruit extract against HT29 cells associated with p53 upregulation and inhibition of NF-?B translocation. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2018;12:657–671. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S155115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun L, Zhang J, Lu X, Zhang L, Zhang Y. Evaluation to the antioxidant activity of total flavonoids extract from persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) leaves. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011;49:2689–2696. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jayaprakasha GK, Negi PS, Sikder S, Rao LJ, Sakariah KK. Antibacterial activity of Citrus reticulata peel extracts Z. Naturforsch. 2000;55:1030–1034. doi: 10.1515/znc-2000-11-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yen G, Hsieh P. Antioxidant activity and scavenging effects on active oxygen of xylose-lysine Maillard reaction products. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1995;67:415–420. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740670320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hagerman AE, Riedl KM, Jones GA, Sovik KN, Ritchard NT, Hartzfeld PW, Riechel TL. High molecular weight plant polyphenolics (tannins) as biological antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:1887–1892. doi: 10.1021/jf970975b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gauthier C, Legault J, Lavoie S, Rondeau S, Tremblay S, Pichette A. Synthesis and cytotoxicity of bidesmosidicbetulin and betulinic acid saponins. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:72–81. doi: 10.1021/np800579x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pyo JS, Roh SH, Kim DK, Lee JG, Lee YY, Hong SS, Kwon SW, Park JH. Anti-cancer effect of Betulin on a human lung cancer cell line: a pharmacoproteomic approach using 2 D SDS PAGE coupled with nano-HPLC tandem mass spectrometry. Planta Med. 2009;75:127–131. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sarek J, Kvasnica M, Urban M, Klinot J, Hajduch M. Correlation of cytotoxic activity of betulinines and their hydroxy analogues. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2005;15:4196–4200. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mullauer FB, Kessler JH, Medema JP. Betulin is a potent anti-tumor agent that is enhanced by cholesterol. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Esposito K, Giugliano D. The metabolic syndrome and inflammation: association or causation? Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2004;14:228–232. doi: 10.1016/S0939-4753(04)80048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krakauer T. Molecular therapeutic targets in inflammation: cyclooxygenase and NF-kappaB. Curr. Drug Targets- Inflamm. Allergy. 2004;3:317–324. doi: 10.2174/1568010043343714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ohshima H, Bartsch H. Chronic infections and inflammatory processes as cancer risk factors: possible role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 1994;305:253–264. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.González-Gallego J, Sánchez-Campos S, Tunon M. Anti-inflammatory properties of dietary flavonoids. Nutr. Hosp. 2007;22:287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pathak SK, Sharma RA, Steward WP, Mellon JK, Griffiths TR, Gescher AJ. Oxidative stress and cyclooxygenase activity in prostate carcinogenesis: targets for chemopreventive strategies. Eur. J. Cancer. 2005;41:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hughes FJ, Buttery LD, Hukkanen MV, O'Donnell A, Maclouf J, Polak JM. Cytokine-induced prostaglandin E2 synthesis and cyclooxygenase-2 activity are regulated both by a nitric oxide-dependent and -independent mechanism in rat osteoblasts in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:1776–1782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jachak SM. Cyclooxygenase inhibitory natural products: current status. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006;13:659–678. doi: 10.2174/092986706776055698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]