Abstract

A study of anaerobic sediments below cyanobacterial mats of a low-salinity meltwater pond called Orange Pond on the McMurdo Ice Shelf at temperatures simulating those in the summer season (<5°C) revealed that both sulfate reduction and methane production were important terminal anaerobic processes. Addition of [2-14C]acetate to sediment samples resulted in the passage of label mainly to CO2. Acetate addition (0 to 27 mM) had little effect on methanogenesis (a 1.1-fold increase), and while the rate of acetate dissimilation was greater than the rate of methane production (6.4 nmol cm−3 h−1 compared to 2.5 to 6 nmol cm−3 h−1), the portion of methane production attributed to acetate cleavage was <2%. Substantial increases in the methane production rate were observed with H2 (2.4-fold), and H2 uptake was totally accounted for by methane production under physiological conditions. Formate also stimulated methane production (twofold), presumably through H2 release mediated through hydrogen lyase. Addition of sulfate up to 50-fold the natural levels in the sediment (interstitial concentration, ∼0.3 mM) did not substantially inhibit methanogenesis, but the process was inhibited by 50-fold chloride (36 mM). No net rate of methane oxidation was observed when sediments were incubated anaerobically, and denitrification rates were substantially lower than rates for sulfate reduction and methanogenesis. The results indicate that carbon flow from acetate is coupled mainly to sulfate reduction and that methane is largely generated from H2 and CO2 where chloride, but not sulfate, has a modulating role. Rates of methanogenesis at in situ temperatures were four- to fivefold less than maximal rates found at 20°C.

The McMurdo Ice Shelf is in the northwestern corner of the Ross Ice Shelf, between Ross Island and Brown Peninsula. An area of about 1,500 km2 is known as Dirty Ice, an ablation zone covered by gravel. A large portion of this gravel originates from marine sediment, and much of the shelf ice is frozen seawater (7). During the summer melt, the area is covered by ponds of a wide size range between hummocks with a vertical profile as high as 20 m (12). Ponds form and disappear again over decades, leading to a wave-like cycling of the shelf surface through ponds and hummocks (2). Freezing, thawing, and evaporation often lead to pronounced solute gradients and water column stratification (9a).

The bottoms of these ponds are covered with thick mats consisting of cyanobacteria, diatoms, and green algae (11, 12), below which is a layer of anaerobic sediment. Variations in chemical and physical conditions between the ponds lead to community differentiation within and between the mats and to differences in mat morphology, thus creating in a small area a variety of modern unlithified stromatolites unique on Earth (31). The mats harbor a small population of grazers, mainly the rotifer Philodinia gregaria, but their activity does not appear to have a key function in the ecosystem. Apart from the discrete ponds on the ice shelf, there are also ponds in estuaries. These ponds are connected by seawater at high tide and also contain diverse assemblages of algae and cyanobacteria with primary production characteristics similar to those for discrete ponds (8).

Previous studies have shown that ponds may vary in conductivity, from highly saline to almost freshwater (12). While considerable knowledge has been gained about the photosynthetic activity and carbon flux attributed to the algal mats of these ponds, together with physical and chemical characteristics (2, 11), no studies on the processes occurring in the underlying pond sediments have been published.

In this paper we describe some of the major heterotrophic processes occurring in the sediments of a low-salinity meltwater pond, Orange Pond, near Bratina Island. The rates of terminal anaerobic processes are given together with the contributions of these processes to terminal carbon and electron flow, and we discuss their significance for carbon flux in the mat-sediment ecocouple.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Location of sampling area and study pond.

The study area was immediately south of Bratina Island (78°00′S, 165°35′E). The area was surveyed in January 1991 by B. R. George (New Zealand Department of Survey and Land Information, K 191, plan 37/165A). The study pond was Orange Pond, the water chemistry and algal mats of which have been described previously (11, 12, 29). The pond is oval, covers an area of approximately 27 m2, and has a maximum water depth of 1 m. Underlying the cyanobacterial mat at the bottom of the pond was a layer of anaerobic sediment at a depth of about 18 to 20 cm.

Sampling procedure.

Sediments were sampled by using 60-ml syringes from which the tips had been cut off. Cores were taken of the entire thawed portion of sediment. For depth profile studies, cores were cut into 2-cm segments after removal of the algal mat. Segments of identical depth were pooled, mixed, and then transferred to containers, which were sealed and frozen for chemical studies or maintained at <5°C for biological studies. Samplings along a transect were carried out at sites ranging from 2.2 m landwards from the water’s edge (51 cm above the pond level) to 1.5 m into the pond (28 cm deep). For kinetic studies of anaerobic processes, unless stated otherwise, sediment samples taken at a water depth of 10 to 20 cm, from 0 to 5 cm below the cyanobacterial mat, were pooled and stored at <5°C in sealed, near-filled containers.

Incubation techniques.

For studies without radiolabel, sediment was transferred to 70-ml serum bottles (10 cm3) or 26.5-ml Balch tubes (5 cm3) under a gas stream of 70% N2–30% CO2. Degassed pond water was added in a ratio of 1 part of water to 2 parts of sediment by volume. Tubes or bottles were sealed with butyl septum stoppers secured with aluminum closures and were incubated at 2 to 4°C in a cold room for 3 days to 6 weeks. The effects of electron acceptors and short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) on methanogenesis were tested by the addition of an electron acceptor (nitrate or sulfate) or SCFA to incubation mixtures in the range of 0 to 20 mM (final added concentration) in the interstitial water. The effect of hydrogen on methanogenesis was tested by the addition of the gas to incubation mixtures in tubes in the range of 0 to 30 kPa. Tubes were incubated by using a radial shaker as previously described (16) to minimize the slow diffusion of the gas from the gas phase to the sediment. Methane oxidation was determined by the addition of methane to septum-stoppered serum bottles (initial concentration in an air-gas phase, 1% [vol/vol]) containing sediment taken from 0 to 1 cm below the cyanobacterial mat. Denitrification was determined by incubating sediments anoxically in the presence of nitrate (0.7 μg of atomic N cm−3).

Incubations investigating the partitioning of acetate to methane and CO2 were carried out on sediments taken at 2-cm depth intervals at a water depth of 20 cm. [2-14C]acetate (0.2 ml; 51 mCi mmol−1; 25 μCi ml−1) was added via syringe to butyl septum-stoppered 70-ml serum bottles, each containing 10 ml of sediment (taken from 2-cm depth intervals) diluted with 5 ml of degassed pond water under a gas mixture of 70% N2–30% CO2. Slurries were incubated at 2 to 4°C. Bottles also contained a glass center tube for CO2 capture by NaOH. Incubation was terminated by the addition of 0.3 ml of 50% H2SO4 to the sediment slurry, immediately preceded by the addition of 2.5 ml of 3 N NaOH to the center well, and bottles were stored for 2 h to allow for complete absorption of CO2 before analysis.

Studies on the turnover of acetate were carried out by the addition of 0.2 ml of [2-14C]acetate (51 mCi mmol−1; 25 μCi ml−1) via syringe to butyl septum-stoppered Balch tubes containing 12 ml of sediment slurry made up of 2 parts of pond sediment (depth, 0 to 5 cm below the cyanobacterial mat) to 1 part of degassed pond water under a gas stream of 70% N2–30% CO2. Sediments were incubated at 2 to 4°C. At various intervals over 20 days, samples (0.5 to 1 ml) were withdrawn via syringe by using a wide-bore needle and spun at 7,000 × g for 20 min at 7°C, and the supernatants were stored at −18°C until they were analyzed.

Studies on sulfate reduction were carried out by incubation of 2 ml of sediment slurry (2 parts of sediment to 1 part of degassed pond water by volume) in plastic syringes (3.0 ml), the sawn-off ends of which were sealed with butyl septum stoppers. Two microcuries of Na235SO4 (100 mCi mmol−1; 10 μCi ml−1) was injected into each sample, which was shaken to distribute the label evenly and then incubated at 2 to 4°C.

Analysis of radioactive incubations.

For the analysis of radiolabelled gases from [2-14C]acetate incubations, negative gas pressure in bottles as a result of CO2 absorption was relieved by the injection of nitrogen to give a positive pressure. The total volume of gas was determined by recording the volume of excess gas forced into the syringe. The amount of label in methane was determined by injection of 1-ml volumes of gas from gas-equilibrated bottles into scintillation vials sealed with butyl septum stoppers and counting in 20 ml of toluene-based scintillant as previously described (16). The label in carbon dioxide was counted in toluene-methanol scintillant (15). Analysis of radiolabelled acetate in turnover studies was carried out by high-pressure liquid chromatography of the supernatant as described previously (28) except that a Brownlee Polypore H column was used; acetate in the eluate was collected in a scintillation vial and counted in a toluene-based scintillant.

For the analysis of 35SO42− incubations, sediment in a syringe was injected into the chamber of a sulfide distillation apparatus in which the top was modified to take a 3-ml syringe. The chamber contained 10 ml of 3 N HCl, which was sparged with a gas stream of O2-free nitrogen. Released sulfide was trapped in two serial traps, each containing 20 ml of 1% zinc acetate. Portions of distillate and remaining acidified sample were counted by liquid scintillation procedures for determinations of 35S2− and 35SO42−. 35SO42− counts were confirmed by the addition of a reducing agent to the chamber (16) and distillation into a second series of traps. The evolved 35S2−, together with that from sulfate reduction, was found to account for 85 to 90% of the initial 35SO42− added. 35S2− from sulfate reduction accounted for nearly 40% of the initial 35SO42− over a 15-day time course.

Sulfate levels in the interstitial water were determined as described below after centrifugation of parallel incubations (6,000 × g for 15 min at 2°C) at time zero and at the completion of incubations, respectively.

Rates of sulfate reduction were determined as described previously (16) and are expressed as nanomoles of sulfate reduced per cubic centimeter per hour.

Analysis of nonradioactive incubations.

Methane levels were determined by gas chromatography on a Porapak Q column connected to a flame ionization detector in a Hewlett-Packard gas chromatograph. Analysis of hydrogen was carried out with a Fisher-Hamilton gas partitioner equipped with a thermal conductivity detector. Gas samples were fractionated with argon as the carrier gas on a 2-m Molecular Sieve 13X column at room temperature. SCFA were analyzed by gas chromatography (18) after centrifugation of sediments or sediment slurries (at 6,000 × g for 20 min at 2°C) and acidification of the supernatant. N2O produced in the denitrification enzyme assay was analyzed by electron capture detection after gas chromatography (21).

Chemical analysis of sediments.

Sediment was dried at 30°C for measurement of pH, sulfate, and sodium. pH was measured in a slurry prepared from 1 part of sediment to 2.5 parts of distilled water (20) or in the interstitial water. Sodium was extracted with water and then measured by flame emission spectrometry. Sulfate levels were determined by turbidometry after phosphate extraction. Sediment was extracted with 1 M KCl for colorimetric determination of levels of soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP), ammonia-N (25), nitrite-N, and nitrate-N (after Cd reduction). Chloride levels were determined colorimetrically after water extraction. Sediment was dried at 105°C for dry weight and then ashed at 500°C for ash-free dry weight (organic matter). The concentration of methane in the sediment was determined by gas chromatography of the headspace gas over the slurry from a 2-cm core segment and 5 ml of water in a stoppered Balch tube after equilibration by vigorous shaking for several minutes. Water analyses were carried out by the same methods used for sediments. Total nitrogen in water was measured as nitrate after photooxidation. Where methods are not specifically referenced, American Public Health Association methods (6) were used.

Chemicals.

All chemicals were of reagent grade and were obtained from commercial sources. The radioisotopes [2-14C]acetate (51 mCi · mmol−1) and Na235SO4 (100 mCi · mmol−1) were obtained from the Radiochemical Center, Amersham, Little Chalfont, England.

RESULTS

Physical and chemical characteristics of sediment along pond transect.

The chemical composition of Orange Pond sediments along the transect is summarized in Table 1. Sulfate levels were highest above the waterline (i.e., on the land) at 0- to 2-cm depths and decreased with increasing depth. Lower levels of sulfate were present in sediments taken at and below the waterline (i.e., at the pond’s edge and in the pond). No clear relationship existed between depth and sodium concentrations in sediments at different points along the transect. SRP levels were highest in the 0- to 2-cm depth zone below the waterline. The highest levels of Kjeldahl nitrogen were found in the 0- to 4-cm depth zone above the waterline, in the 4- to 8-cm depth zone at the waterline, and at depths of >8 cm below the waterline. Trends for NH4 levels were similar, but below the waterline there was no relationship between depth and concentration. The highest pH values were in the 0- to 2-cm depth range at all points along the transect.

TABLE 1.

Chemical analysis of Orange Pond sediments

| Chemical | Concn (mg · kg [dry wt] of sediment−1)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Above waterlineb | Waterlinec | Below waterlined | |

| Na+ | 1,014–1,642 (0–18) | 743–1,637 (0–16) | 801–1,234 (0–16) |

| Cl− | 150–300 (0–6) | ||

| SO42− | 544–1,198 (0–2) | 82–129 (0–16) | 13–86 (0–14) |

| 160–882 (2–8) | |||

| 65–465 (8–18) | |||

| SRP | 0.01–0.07 (0–18) | 0.06–0.14 (0–16) | 0.11–0.56 (0–2) |

| 0.05–0.13 (2–16) | |||

| Kjeldahl nitrogen | 200–640 (0–4) | 130–200 (0–4, 8–16) | 83–320 (0–8) |

| 61–160 (4–18) | 390–490 (4–8) | 260–670 (8–14) | |

| NH4+ | 2–66 (0–4) | 2–3 (0–4) | 15–41 (0–18) |

| 1–3 (4–18) | 16–42 (4–18) | ||

| NO3− | 11–108 (0–4) | 4–16 (0–18) | 1–4 (0–18) |

| 2–40 (4–18) | |||

| NO2− | 0.01–0.23 (0–18) | 0.02–0.28 (0–18) | 0–0.18 (0–18) |

Values in parentheses are depth ranges (in centimeters).

Samples were taken at 100 and 220 cm landwards from the water’s edge. The pH values of the sediments were 6.9 to 9.3 at depths of 0 to 4 cm and 7.1 to 8.8 at depths of 4 to 18 cm.

Sediments had pH values of 9.1 to 9.4 at depths of 0 to 4 cm and 8.2 to 8.4 at depths of 4 to 18 cm.

Samples were taken from the pond at 50, 100, and 150 cm from the water’s edge. Sediments had pH values of 8.1 to 9.2 at depths of 0 to 4 cm and 7.6 to 8.3 at depths of 4 to 18 cm.

The dry weight as a percentage of the wet weight of the sediment was >80% above the waterline, 75 to 80% at the waterline, and 70 to 75% below the waterline, and the organic matter content ranged from 1 to 4% of the dry weight. The density of sediments below the waterline ranged from 1.1 to 1.5 g (dry weight) ml−1 (data not tabulated).

Rates of methanogenesis and in situ levels of methane.

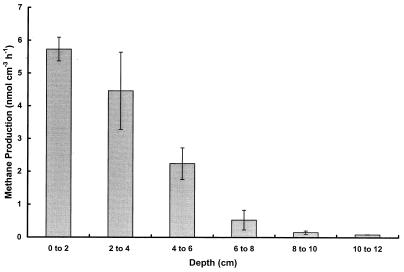

Figure 1 shows the rates of methanogenesis versus depth for sediment 50 cm below the waterline. The highest rates (5.5 nmol · cm−3 h−1) were obtained for sediment at depths of 0 to 2 cm. At and above the waterline, rates of methanogenesis were <0.2 nmol cm−3 h−1. Rate data did not reflect in situ levels of methane (Table 2). This is particularly evident for the profile 50 cm below the waterline, where methane levels were highest at depths of 12 to 14 cm. Since the most productive sediments were those from below the waterline, and in the depth range of 0 to 5 cm, all subsequent experiments were carried out with sediments taken from this zone.

FIG. 1.

Depth profile for methanogenesis in sediments taken from Orange Pond 50 cm below the waterline. Values are means of at least duplicate determinations ± 1 standard deviation.

TABLE 2.

Methane profiles along transect at Orange Pond

| Segment depth (cm) | Methane concn (nmol · cm−3) at the following horizontal distance from the pond’s edge and elevationa:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220, 51 | 100, 27 | 0, 0 | −50, −9 | −100, −17 | −150, −28 | |

| 0–2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 39 |

| 2–4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 87 |

| 4–6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 25 | 82 |

| 6–8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 46 | 19 | 67 |

| 8–10 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 82 | 17 | 86 |

| 10–12 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 89 | 14 | 88 |

| 12–14 | 0 | 0 | 97 | 120 | 14 | 92 |

| 14–16 | 0 | 0 | 216 | |||

| 16–18 | 0 | 0 | ||||

In centimeters. The first number in each boxhead is the horizontal distance, and the second is the elevation. Negative numbers refer to samples in the pond and below water level.

Fates of acetate and hydrogen.

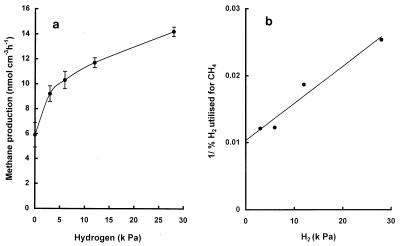

[2-14C]acetate was added to sediments in order to determine whether the methyl group intermediate was utilized for methanogenesis or oxidized by sulfate-reducing bacteria. The proportion of the methyl group oxidized to CO2 is expressed by the term pox, calculated as 14CO2/(14CO2 + 14CH4). Table 3 shows that for sediment taken at various depths at 60 cm below the waterline, the pox was >0.96, indicating that acetate was mainly oxidized to CO2 in these sediments. When hydrogen was added to sediments, methanogenesis was stimulated as much as 2.4-fold (Fig. 2a) and measurements of hydrogen utilized revealed that methane accounted for >82 to <40% of the hydrogen utilized at initial H2 levels ranging from 3 to 28 kPa (Table 4). Transformation of the results in Table 4 (plotting 1/percent H2 utilized for CH4 versus initial H2 [in kilopascals] [Fig. 2b]) predicts that under physiological conditions (H2 <5 Pa), methanogenesis would account for all of the hydrogen (1/intercept >95%).

TABLE 3.

Ratio of counts in methane and CO2 produced from the degradation of [2-14C]acetate at different depths of sediment core taken from Orange Pond at 60 cm below the waterline

| Depth (cm) | 14CH4 (102 dpm · h−1)a | 14CO2 (104 dpm · h−1)a | poxb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 | 0.09 | 1.05 | 0.99 |

| 2–4 | 0.18 | 0.88 | 0.99 |

| 4–6 | 2.95 | 1.11 | 0.97 |

| 6–8 | 2.54 | 1.04 | 0.97 |

| 8–10 | 3.37 | 1.03 | 0.97 |

Determined over a time course of 240 h in which production of 14CO2 and 14CH4 was linear.

pox = 14CO2/(14CO2 + 14CH4).

FIG. 2.

Stimulation of methanogenesis by H2 (a) and plot of the reciprocal of the percentage of H2 utilized for methane versus initial H2 (in kilopascals) (b). The level of H2 in the unamended system was <5 kPa. Values are means of at least duplicate determinations ± 1 standard deviation.

TABLE 4.

Proportion of hydrogen utilized for methane in Orange Pond sediments

| Initial H2 level (kPa) | Amt of H2 utilized (μmol)a | Amt of methane produced (μmol)a | % H2 utilized for methane productionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 3.30 ± 0.54 | 0 |

| 3 | 8.96 ± 1.76 | 5.14 ± 0.35 | 82.1 |

| 6 | 12.21 ± 0.41 | 5.79 ± 0.39 | 81.6 |

| 12 | 23.73 ± 6.27 | 6.48 ± 0.22 | 53.5 |

| 28 | 46.44 ± 5.50 | 7.88 ± 0.21 | 39.4 |

Determined after 74 h of incubation. Values are means of at least duplicate determinations ± standard deviation.

Determined according to the equation CO2 + 4H2 → CH4 + 2H2O in which methane was subtracted from the control.

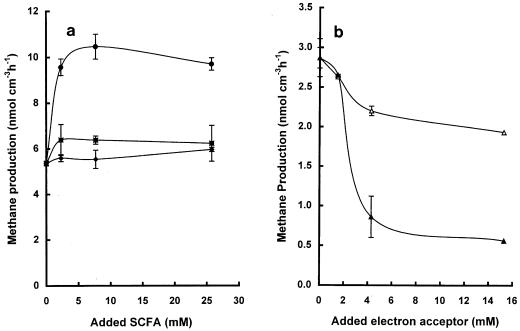

Effects of added short-chain volatile fatty acids on rates of methane production.

Addition of SCFA to sediments (final added concentrations, 0 to 25 mM in the interstitial water) stimulated methanogenesis in decreasing order as follows: formate (2-fold) > butyrate (1.25-fold) > acetate (1.1-fold) (Fig. 3a).

FIG. 3.

Effects of SCFA additions (a) and electron acceptors (b) on methanogenesis. Levels of acetate (⧫), butyrate (■), and formate (●) in the sediment interstitial water of unamended systems were 1.8, 0.05, and <0.02 mM, respectively. Levels of nitrate (▴) and sulfate (▵) in unamended systems were <0.01 and 0.3 mM, respectively. Values are means of at least duplicate determinations ± 1 standard deviation.

Effect of nitrate and effect of sulfate and NaCl on methanogenesis.

Addition of sodium sulfate at levels in the range of 0 to 15.3 mM inhibited methanogenesis slightly, whereas addition of nitrate in the same concentration range inhibited the process substantially (Fig. 3b). Addition of NaCl at low levels (12 mM) did not inhibit methanogenesis, but >50% inhibition occurred when the salt was present at higher levels (36 mM).

Sulfate reduction rate versus methanogenesis and acetate dissimilation rates.

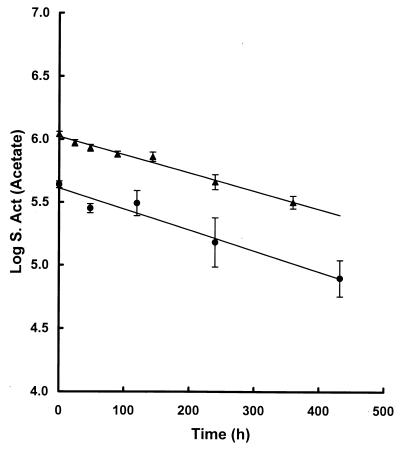

Determinations of the sulfate reduction, methanogenesis, and acetate dissimilation rates for sediments are shown in Table 5. Rates of acetate dissimilation were determined from the turnover rate constants obtained from the slopes of the plots in Fig. 4 multiplied by the pool size. Rates of sulfate reduction exceeded methanogenesis rates by a ratio of 3. Based on the value of pox for acetate degradation and rates of acetate dissimilation together with the rates of the two terminal processes, acetate was calculated to contribute to 2% of methane production and 70% of sulfate reduction. On the other hand, H2 was nearly all utilized for methanogenesis (Fig. 2b).

TABLE 5.

Rates for sulfate reduction, methanogenesis, and acetate dissimilation in Orange Pond sediments and calculations of the contribution of acetate to methanogenesis and sulfate reduction

| Yr of samplinga | Sulfate reduction rate (nmol · cm−3 h−1)b | Methane production rate (nmol · cm−3 h−1)b | Acetate dissimilation rate (nmol · cm−3 h−1)c | poxd | % CH4 from acetatee | % Sulfate reduction from acetate oxidationf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 10.99 ± 1.87 | 3.32 ± 1.21 | 7.2 | 0.99 | 2.00 | 65.0 |

| 1998 | 6.83 ± 0.82 | 1.78 ± 0.23 | 5.6 | 0.99 | 3.10 | 81.2 |

Sediments were taken in two separate summer seasons.

Values are means of at least duplicate determinations ± 1 standard deviation.

Determined from the slopes of the plots (Fig. 4) × 2.303 × acetate pool size.

Obtained from Table 3.

Based on the equation CH3COO− + H+ → CH4 + CO2 and determined from [nanomoles of acetate per cubic centimeter per hour × (1 − pox)/nanomoles of CH4 per cubic centimeter per hour] × 100.

Based on the equation CH3COO− + SO42− → 2HCO3− + HS− and determined from (nanomoles of acetate per cubic centimeter per hour × pox/nanomoles of sulfate reduced per cubic centimeter per hour) × 100.

FIG. 4.

Decrease in the log specific radioactivity (S. Act) of acetate after addition of [2-14C]acetate to sediments. Plots are for sediments taken from two different summer seasons, 1994 and 1998. Average pool sizes were 2.2 (▴) and 1.8 (●) μmol · cm−3 of sediment, respectively. Values are means of duplicate determinations ± 1 standard deviation.

Determination of methane oxidation and denitrification rates in sediments.

Rates of methane oxidation in surface sediments under aerobic conditions almost matched the rates of methanogenesis found in the deeper anaerobic sediments (Tables 5 and 6). No net rate of methane oxidation was observed for the same sediment incubated under anaerobic conditions. Sediments taken from both the shallow and deeper profiles showed a capacity for denitrification, but the rates were substantially lower than those for methanogenesis and sulfate reduction.

TABLE 6.

Estimates of methane oxidation and denitrification in sediments of Orange Pond

| Process | Conditions | Depth below cyanobacterial mat (cm) | Rate (nmol of CH4 or g of atomic N · cm−3 h−1)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane oxidation | Anaerobic | 0–1 | 0b |

| Aerobic | 0–1 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | |

| Denitrification | Anaerobic | 0–1 | 0.83 ± 0.24 |

| 0–5 | 1.11 ± 0.34 |

Values are means of at least duplicate determinations ± 1 standard deviation and are for sediments taken at water depths between 10 and 20 cm and incubated at 4°C.

Sediments showed net production of methane.

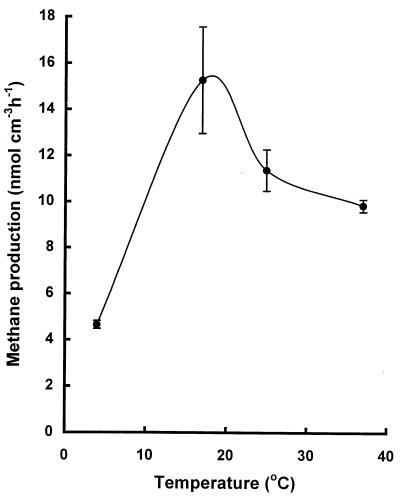

Optimal temperature for methanogenesis.

The highest rate of methanogenesis was at 20°C (Fig. 5). Rates at 4°C were about 20% of the maximum.

FIG. 5.

Temperature dependence of methanogenesis in sediments. Values are means of triplicate determinations ± 1 standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Previous to this work anaerobic microbial processes have been described for antarctic ecosystems including dry valley and coastal lakes (3–5, 14). However there has been no previous documentation of the processes occurring beneath the mats of McMurdo Ice Shelf ponds. In this communication we describe the terminal anaerobic processes occurring in the sediments beneath the cyanobacterial mats of Orange Pond, a low-salinity meltwater pond. Both methanogenesis and sulfate reduction were found to be important terminal events in which the rate ratio (sulfate reduction to methanogenesis) was about 3.

In our previous studies of sulfate reduction and methanogenesis in temperate coastal sediments where active methanogenesis occurred, the pox was >0.5, indicating that a substantial amount of methyl carbon from acetate was converted to methane (16, 17). Furthermore, sulfate addition to such sediments substantially inhibited methanogenesis, indicating the potential for sulfate-reducing organisms to compete for the methanogenic substrates. In a totally methanogenic system, the methyl group of acetate is stoichiometrically converted to methane (30). While Orange Pond sediments were actively methanogenic, the passage of carbon from acetate was mainly to CO2. Acetate did not stimulate methanogenesis, which is unusual in a typical methanogenic environment unless levels of acetate are already saturating. These findings indicate that the Orange Pond sediments were unusual in the context of known anaerobic systems.

Clarification of the results on acetate metabolism was obtained through studies on hydrogen addition, from which we calculated that under physiological conditions, methane could be wholly accounted for by this precursor. The hydrogen addition studies were also consistent with the results on stimulation of methanogenesis by formate, in which the acid was most likely cleaved by formate hydrogen lyase to release CO2 and hydrogen for methanogenesis. Hydrogen as the major precursor of methane is not unusual in the context of Antarctic ecosystems. Ellis-Evans (3) demonstrated from studies with 14CO2 that in sediments of Antarctic lakes H2 and CO2 were the major precursors of methane, and Smith et al. (24) showed that in incubations of sediments from Lake Fryxell the rate of methanogenesis from H2 and CO2 was approximately four times that of acetate cleavage to methane.

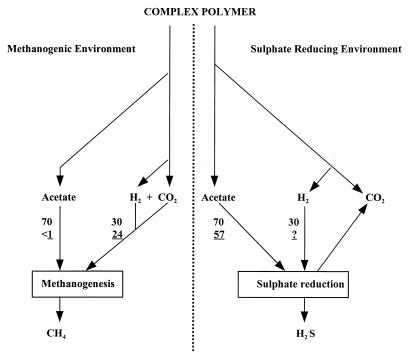

Estimates of the proportions of sulfate reduction and methane production contributed by acetate and hydrogen in Orange Pond sediments are shown in Fig. 6. They are based on rate data (Table 5), together with the data on pox and hydrogen utilization. The diagram also gives the proportions of carbon flow associated with acetate and hydrogen metabolism in methanogenic and sulfate-reducing ecosystems based on known stoichiometric conversions. In Orange Pond sediments the passage of carbon flow is not that of a typically methanogenic or sulfate-reducing ecosystem in that sulfate reduction accounts for most of the acetate metabolized and methane accounts for most of the hydrogen. The fates of the two precursors are therefore partitioned between the two processes. To our knowledge this is the first detailed report of such an event occurring in an anaerobic ecosystem.

FIG. 6.

Carbon flow in methanogenic and sulfate-reducing environments. Numbers that are not underlined refer to the percent contribution to sulfate reduction or methanogenesis from acetate or hydrogen based on the stoichiometry of known anaerobic transformations (30, 32). Underlined numbers are from this study and were calculated as (percent contribution of acetate or H2 to the process of sulfate reduction or methanogenesis × rate of process)/(rate of methanogenesis + rate of sulfate reduction).

There is some precedent for believing that changes in the Gibbs free energy of key processes, differential sensitivities of populations to temperature, and temperature-dependent substrate affinities are key factors in influencing microbial community function at low temperatures and that they contributed to the results we observed. Anaerobic communities consisting of different methanogenic populations utilizing either acetate or hydrogen and with different temperature optima have been described for subarctic peat (26). In anoxic paddy soil, reducing the temperature decreased turnover and the Gibbs free energy of H2-mediated methanogenesis, resulting in decreases in the contribution of H2-utilizing methanogens to overall methanogenesis (1). A detailed study by Nedwell and Rutter (19) demonstrated that temperature affected growth rate and substrate affinity in two psychrotolerant Antarctic bacteria and that the two organisms responded differently to temperature changes. The net outcome of one or several of the above temperature-dependent factors may be critical to the degree of carbon and electron partitioning between members of an anaerobic community. In Orange Pond sediments this has favored sulfate reducers for the utilization of acetate and H2-utilizing methanogens for the production of methane.

Also contributing to the processes we observed are the physical and biological characteristics of the ponds, e.g., the flux of inorganic ions through the pond system and the decay of the overlying cyanobacterial mat, contributing organic matter to the sediment. Levels of sulfate and, to a lesser extent, Na+ in the sediment were low compared to those in soil adjacent to the pond (Table 1), where mirabilite (Na2SO4 · 10H2O) is deposited (2). It is likely that the latter acts as a reservoir contributing sulfate to the pond sediment via meltwater. However, reoxidation of sulfide at the aerobic-anaerobic interface between microbial mat and sediment may be the major source of sulfate for the most active sediment immediately underneath the microbial mat. The mat is the only significant source of organic carbon in the pond ecosystem (9), and its importance to anaerobic processes is reflected in the substantial stimulation of methanogenesis upon its addition to sediment (18a). The very low levels of NO3− (Table 1) would have precluded denitrification as a significant process. The rates (Table 6) obtained by enzyme assay reflect the capacity of the sediment for denitrification, which is typically several orders of magnitude higher than in situ rates found in long-term anaerobic incubations (13). The potential for denitrification can also explain the substantial inhibition of methanogenesis upon the addition of nitrate to the sediment (Fig. 3b), as it is the preferred electron acceptor in H2-consuming reactions (27). Among other processes that could have contributed to methane production is the reductive demethylation of dimethyl sulfide (DMS). DeMora and colleagues have detected DMS in the water column of the pond systems (2). However, while sediments have the capability of producing DMS from dimethylsulfoniopropionate, DMS was not detected in incubation mixtures degrading the cyanobacterial mat, nor did its addition to sediments stimulate methanogenesis, with or without hydrogen addition (18a). Oxidation of methane occurred in surface sediment under aerobic conditions at rates almost matching rates of methane production from the deeper anaerobic sediments (Tables 5 and 6), but the same sediments under anaerobic conditions produced methane. Except for the first few millimeters below the mat, the absence of oxygen (9) limits methane oxidation. However, the measured methane oxidation rates and the methane gradients in Table 2 suggest that most of the anaerobically generated methane does not leave the mat-sediment system but is re-oxidized.

Inhibition of methanogenesis by the addition of salt was most likely due to the effects of osmotic stress action on the wider anaerobic bacterial community. It is unlikely that salt directly inhibited methanogenesis, as the process is dependent on sodium (23). The effects of salinity on the anaerobic processes in sediments of ponds of varying salinity will be described in a future paper (18b).

Of all the factors, temperature, via the mechanisms already detailed, is likely to have been the major factor limiting anaerobic degradation in Orange Pond. During the summer the temperature of thawed Orange Pond sediments ranged between 7.1 and −1.5°C. Rates of degradation as determined by methanogenesis in this temperature range were substantially lower than those determined for the same sediments incubated at higher temperatures (Fig. 5). The pond temperatures were also below the growth temperature optima of many psychrotolerant and psychrophilic organisms (10, 22).

The partitioning of carbon and electron flow between methanogenesis and sulfate reduction in sediments of Orange Pond ensures that CO2 production is maximized via acetate oxidation for uptake by the cyanobacterial community for photosynthesis, in a process occurring at relatively low sulfate concentrations. Our results suggest, however, that any methane that is produced is likely to be oxidized to CO2 in an aerobic sediment zone immediately below the cyanobacterial mat. The net effect of the sediment processes is total conversion to CO2 by a combination of anaerobic degradation and methane oxidation, the result of which is a tight coupling between phototrophic and heterotrophic processes via CO2, the lack of which would limit primary production (9).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are greatly indebted to Clive Howard-Williams, Ian Hawes, and Anne-Marie Schwartz for introducing us to antarctic research and for their support. We thank the personnel of Antarctica New Zealand VXE6 for their excellent support.

Funding for this work was provided by contracts with the New Zealand Foundation for Research, Science and Technology. The work was also supported by grants from the New Zealand Lottery Science Board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Conrad R, Schultz H, Babbel M. Temperature limitation of hydrogen turnover and methanogenesis in anoxic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1994;45:281–289. [Google Scholar]

- 2.deMora S J, Whitehead R F, Gregory M. The chemical composition of glacial meltwater ponds and streams on the McMurdo Ice Shelf, Antarctica. Antarctic Sci. 1994;6:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis-Evans J C. Methane in maritime Antarctic freshwater lakes. Polar Biol. 1984;3:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis-Evans J C, Sanders M W. Observations on microbial activity in a seasonally anoxic nutrient-enriched maritime Antarctic lake. Polar Biol. 1988;8:311–318. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franzmann P D, Roberts N J, Manusco C A, Burton H R, McMeekin T A. Methane production in meromictic Ace Lake, Antarctica. Hydrobiology. 1991;210:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg A E, Clesceri L S, Eaton A D, editors. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 18th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart C P. Holocene megafauna in the McMurdo Ice Shelf sediments—fossilization and implications for glacial processes. Antarctic J. 1990;25:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawes I, Howard-Williams C, Schwarz A-M J, Downes M T. Environment and microbial communities in a tidal lagoon at Bratina Island, McMurdo Ice Shelf, Antarctica. In: Battaglia B, Valencia J, Walton D W H, editors. Antartic communities. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawes I, Howard-Williams C, Pridmore R D. Environmental control of microbial biomass in the ponds of the McMurdo Ice Shelf, Antarctica. Arch Hydrobiol. 1993;127:271–287. [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Hawes, I. 1995. Personal communication.

- 10.Herbert R A. The ecology and physiology of psychrophilic organisms. In: Herbert R A, Codd G A, editors. Microbes in extreme environments. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard-Williams C, Pridmore R, Downes M T, Vincent W F. Microbial biomass, photosynthesis and chlorophyll a related pigments in the ponds of the McMurdo Ice Shelf, Antarctica. Antarctic Sci. 1989;1:125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard-Williams C, Pridmore R D, Broady P A, Vincent W F. Environmental and biological variability in the McMurdo Ice Shelf ecosystem. In: Kerry K R, Hempel G, editors. Antarctic ecosystems: ecological change and conservation. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaspar H F, Tiedje J M, Firestone R B. Denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia in digested sludge. Can J Microbiol. 1981;27:878–885. doi: 10.1139/m81-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konda T, Takii S, Fukui M, Kusuoka Y, Matsumoto G I, Torii T. Vertical distribution of bacterial population in Lake Fryxell, an Antarctic lake. Jpn J Limnol. 1994;55:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mountfort D O, Asher R A. Changes in proportions of acetate and carbon dioxide used as methane precursors during the anaerobic digestion of bovine waste. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:648–654. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.4.648-654.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mountfort D O, Asher R A, Mays E L, Tiedje J M. Carbon and electron flow in mud and sandflat intertidal sediments at Delaware Inlet, Nelson, New Zealand. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:686–694. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.4.686-694.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mountfort D O, Asher R A. Role of sulfate reduction versus methanogenesis in terminal carbon flow in polluted intertidal sediment of Waimea Inlet, Nelson, New Zealand. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;42:252–258. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.2.252-258.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mountfort D O, Rhodes L L. Anaerobic growth and fermentation characteristics of Paecilomyces lilacinus isolated from mullet gut. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1963–1968. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.7.1963-1968.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Mountfort, D. O. Unpublished data.

- 18b.Mountfort, D. O., et al. Unpublished data.

- 19.Nedwell D B, Rutter M. Influence of temperature on growth rate and competition between two psychrotolerant Antarctic bacteria: low temperature diminishes affinity for substrate uptake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1984–1992. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.1984-1992.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page A L, editor. Methods of soil analysis, part 2. Madison, Wis: American Society of Agronomy Inc., Soil Science Society of America Inc.; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Priscu J C, Downes M T. Microbial activity in the surficial sediments of an oligotrophic and eutrophic lake, with particular reference to dissimilatory nitrate reduction. Arch Hydrobiol. 1987;108:385–469. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell N J. Biochemical differences between psychrophilic and psychrotolerant micro-organisms. In: Guerrero R, Pedros-Alio C, editors. Trends in microbial ecology. Barcelona, Spain: Spanish Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schonheit P, Biemborn D. Presence of a Na+/H+ antiporter in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum and its role in Na+ dependent methanogenesis. Arch Microbiol. 1985;140:247–251. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith R L, Millar L G, Howes B L. The geochemistry of methane in Lake Fryxell, an amictic, permanently ice-covered, antarctic lake. Biogeochemistry. 1993;21:95–115. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solorzano L. Determination of ammonia in natural waters by the phenol-hypochlorite method. Limnol Oceanogr. 1969;14:799–801. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svensson B H. Different temperature optima for methane formation when enrichments from acid peat are supplemented with acetate or hydrogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:389–394. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.2.389-394.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thauer R K, Jungerman K, Decker K. Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1977;41:100–180. doi: 10.1128/br.41.1.100-180.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Titus E, Ahearn G A. Short chain fatty acid transport in the intestine of a herbivorous teleost. J Exp Biol. 1988;135:77–94. doi: 10.1242/jeb.135.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vincent W F, Casternholz R W, Downes M T, Howard-Williams C. Antarctic cyanobacteria: light, nutrients, and photosynthesis in the microbial mat environment. J Phycol. 1993;29:745–755. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogels G D, Keltjens J T, van der Drift C. Biochemistry of methane production. In: Zehnder A J B, editor. Biology of anaerobic organisms. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1988. pp. 707–770. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wharton R A, Parker B C, Simmons G M. Distribution, species composition and morphology of algal mats in Antarctic Dry Valley lakes. Phycologia. 1983;22:355–365. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Widdel F. Microbiology and ecology of sulfate and sulfur reducing bacteria. In: Zehnder A J B, editor. Biology of anaerobic organisms. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1988. pp. 469–585. [Google Scholar]