Abstract

Bacteria in the Desulfovibrionaceae family, which contribute to S element turnover as sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and disproportionation of partially oxidized sulfoxy anions, have been extensively investigated since the importance of the sulfur cycle emerged. Novel species belonging to this taxon are frequently reported, because they exist in various environments and are easy to culture using established methods. Due to the rapid expansion of the taxon, correction and reclassification have been conducted. The development of high-throughput sequencing facilitated rapid expansion of genome sequence database. Genome-based criteria, based on these databases, proved to be potential classification standard by overcoming the limitations of 16S rRNA-based phylogeny. Although standards methods for taxogenomics are being established, the addition of a novel genus requires extensive calculations with taxa, including many species, such as Desulfovibrionaceae. Thus, the genome-based criteria for classification of Desulfovibrionaceae were established and validated in this study. The average amino-acid identity (AAI) cut-off value, 63.43 ± 0.01, was calculated to be an appropriate criterion for genus delineation of the family Desulfovibrionaceae. By applying the AAI cut-off value, 88 genomes of the Desulfovibrionaceae were divided into 27 genera, which follows the core gene phylogeny results. In this process, two novel genera (Alkalidesulfovibrio and Salidesulfovibrio) and one former invalid genus (“Psychrodesulfovibrio”) were officially proposed. Further, by applying the 95–96% average nucleotide identity (ANI) standard and the 70% digital DNA–DNA hybridization standard values for species delineation of strains that were classified as the same species, five strains have the potential to be newly classified. After verifying that the classification was appropriately performed through relative synonymous codon usage analysis, common characteristics were listed by group. In addition, by detecting metal resistance related genes via in silico analysis, it was confirmed that most strains display metal tolerance.

Keywords: Desulfovbrionaceae, AAI, RSCU, genome, Desulfovibrio, taxogenomics, classification criteria

Introduction

Sulfur is an essential element of biomolecules and an important factor in climate change through direct and indirect effects in the H2SO4 form, which brought attention to the sulfur cycle (Kellogg et al., 1972). The Desulfovibrionaceae family has been identified as one of the major contributor to the sulfur cycle on Earth. Discoveries of novel species are frequently reported as these species exist in various environments and can be easily cultured using well-established methods (Postgate, 1984; Widdel and Bak, 1992). Members of the family Desulfovibrionaceae have been employed as model organisms for sulfate reducing bacteria (SRB). Studies regarding anaerobic respiration have been actively conducted using Desulfovibrio since the 1950s, when dissimilatory sulfate reduction and a sulfate reductase named desulfoviridin (Postgate, 1956) were first identified in Desulfovibrio (Peck, 1959, 1961; Vosjan, 1975; Kobayashi et al., 1982; Barton et al., 1983; Lie et al., 1996; Matias et al., 2005; Pereira, 2008; Keller and Wall, 2011; Keller et al., 2014). Recently, interesting research results have been published on the effect of Desulfovibrionaceae family bacteria on host health. Although the exact correlation and mechanism have not been established, the results showed that the relative abundance of Desulfovibrionaceae was significantly increased in obese and metabolically impaired mice (Just et al., 2018), and the amount of Desulfovibrio spp. detected in the feces of Parkinson’s disease, patients showed a significant correlation with the severity of the disease (Murros et al., 2021). However, Desulfovibrio spp. do not always play negative roles. For example, Desulfovibrio spp. may live in sulfate depleted habitats in syntropy with methanogenic archaea (Scholten et al., 2007). SRB converts sulfate into sulfide, which reacts with heavy metals to form metal sulfide. Subsequently, spontaneous precipitation of metal sulfide achieves bioremediation (Ayangbenro et al., 2018). Aside from precipitation of sulfide, Pseudodesulfovibrio hydrargyri and Pseudodesulfovibrio mercurii are well-known mercury methylating bacteria, and activity against 10 ppb and 1 ppm inorganic Hg has been confirmed (Goñi-Urriza et al., 2020). Desulfovibrio desulfuricans showed resistance and high removal rates at concentrations of 50, 100, and 200 ppm in a mixed solution of cadmium nitrate tetrahydrate, nickel sulfate hexahydrate, and chromium oxide (Jeong et al., 2015). Desulfovibrio magneticus exhibited a sharp decrease in cadmium before the exponential phase when 1.3 ppm cadmium chloride was added to the medium (Arakaki et al., 2002). Nitratidesulfovibrio vulgaris was reported to tolerate a wide range of metal ions, such as 10 ppm Mn(II), 15 ppm Cr(III), 4 ppm Cu(II), 8.5 ppm Ni(II), and 20 ppm Zn(II) (Goulhen et al., 2006).

After the genus Desulfovibrio was first proposed in 1936 (Kluyver and Van Niel, 1936), the first attempt to classify this taxon, based on of DNA composition and physiological and biochemical properties, was crucial in establishing the classification criteria (Postgate and Campbell, 1966). In 2002, the genus Desulfomonas (Moore et al., 1976) was reclassified as a member of the genus Desulfovibrio based on molecular analysis (Loubinoux et al., 2002). Subsequently, the Desulfovibrionaceae family was officially recognized in 2006 (Kuever et al., 2005). The genera Bilophila (Baron et al., 1989), Desulfovibrio (Kluyver and Van Niel, 1936), and Lawsonia (McOrist et al., 1995) were reclassified into this family. Thereafter, Desulfocurvus (Klouche et al., 2009) and Desulfobaculum (Zhao et al., 2012) were added. The addition of several new genera, namely Pseudodesulfovibrio (Cao et al., 2016), Halodesulfovibrio (Shivani et al., 2017), “Mailhella” (Ndongo et al., 2017), Desulfohalovibrio, Desulfocurvibacter (Spring et al., 2019), “Paradesulfovibrio” (Kim et al., 2020), and Desulfolutivibrio (Thiel et al., 2020), finally led to a major reorganization based on the genome sequence data (Waite et al., 2020), resulting in Desulfovibrionaceae currently comprising nine validly published genera (Fundidesulfovibrio, Humidesulfovibrio, Maridesulfovibrio, Megalodesulfovibrio, Nitratidesulfovibrio, Oleidesulfovibrio, Paradesulfovibrio, Paucidesulfovibrio, and Solidesulfovibrio) and three published but not validated genera (“Alteridesulfovibrio,” “Aminidesulfovibrio,” and “Frigididesulfovibrio”) besides the existing genera. Reorganizing the confusing taxonomy of the Desulfovibrionaceae family was completed by adding two valid [Macrodesulfovibrio (Galushko and Kuever, 2020b), Oceanidesulfovibrio (Galushko and Kuever, 2020c)] and one invalid genera [“Psychrodesulfovibrio” (Galushko and Kuever, 2020d)] at the end of 2020 through Bergey’s manual (Galushko and Kuever, 2020a). As of August 2021, the Desulfovibrionaceae family comprised 21 validated genera, one synonym, and five non-validated genera.

The recently introduced classification method using the whole genome has been a powerful alternative to the two-step approach, which combined 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity and DNA–DNA hybridization (DDH) (Chun and Rainey, 2014). A genome sequence-based classification, such as average nucleotide identity (ANI) and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH), was introduced (Richter and Rosselló-Móra, 2009) to improve the resolution between highly similar interspecies sequences caused by the short length of the 16S rRNA sequence (Wambui et al., 2021). However, the resolution was insufficient for classification at the genus level, as it comprised only four nucleotide types. Therefore, as an alternative, the average amino acids identity (AAI)-based classification method was introduced to compare the genome information composed of amino acids (Konstantinidis and Tiedje, 2005b; Chun and Rainey, 2014; Rodriguez-R and Konstantinidis, 2014; Barco et al., 2020). There are several successful cases of reclassification using the whole genome, for example, dividing 39 strains belonging to 27 species of Arcobacter spp. into seven genera (Pérez-Cataluña et al., 2018) and reorganizing 91 genomes belonging to the existing three genera of the order Methylococcales into four genera (Orata et al., 2018). These cases followed a similar methodology, wherein the housekeeping genes were extracted, and phylogeny was performed using the ANI and dDDH values for the delineation of species, and percentage of conserved proteins (POCP) and AAI values for the delineation of genera. As the POCP is calculated using an amino acid sequence, it allows a higher resolution comparison for distant groups than the ANI or dDDH values that use a nucleotide sequence. Further, genome sequence-based reclassification of Epsilonproteobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria, to which SRB are affiliated, had been conducted (Waite et al., 2017, 2020). Although this method is not based on comparing genomic indices, it became the foundation for SRB classification by applying an alternative taxogenomic method based on phylogeny to a vast range of taxa and reorganizing them into a new phylum.

Although the results published in Waite et al. (2020) and Bergey’s manual (Galushko and Kuever, 2020a) almost corrected the confusing taxonomy of the family Desulfovibrionaceae, still issues require further investigation. First, the research did not provide a numerical value for genus delineation. Therefore, researchers proposing a new genus must perform extensive calculations and investigation. Comparing genomic indices becomes increasingly complex when studying large genera. Second, the classification was based solely on phylogeny results, indicating that the genus classification that introduced the numerical standard value comparison of genomic indices, which is considered a formal method of taxonomy, has not been made. Third, several mis-classified groups remain, particularly Cupidesulfovibrio [a genus newly proposed in early 2021 (Wan et al., 2021)] which requires further reclassification because it collides with the genus Nitratidesulfovibrio. Referring to the taxonomic comments on the Desulfovibrionaceae family in the 2020 version of Bergey’s manual (Galushko and Kuever, 2020a), some suggested that several species of Pseudodesulfovibrio, which are related to ‘Paradesulfovibrio onnuriensis’ IOR2T, deserve to be considered as an independent genus.

In this study, we performed phylogeny investigations using core genes extracted from all genomes belonging to Desulfovibrionaceae and roughly divided them into smaller groups. To evaluate the categorization process, several genomic indices, such as G + C content, dDDH, ANI, AAI, and POCP, were explored. Moreover, we not only arranged mis-classified strains at the species level but also proposed new genera reflecting phenotypes of other well-divided groups. This research will provide a genus cut-off genomic index that can be referenced without comparing extensive genome indices with previously reported species. In addition, the metal tolerance enzyme prediction using genome data highlights that the family Desulfovibrionaceae displays tolerance to certain extreme environments.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Sequences

Information on all strains was collected from their related literature (Supplementary Table 1). All genomes of isolates, except for Pseudodesulfovibrio tunisiensis RB22T, registered under the Desulfovibrionaceae family were obtained from two public databases, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and EzBioCloud (Yoon et al., 2017a). Pseudodesulfovibrio tunisiensis RB22T strains were ordered from JCM RICKEN and cultured for two days in DSM143 medium injected with H2/CO2 gas. Afterward, their genomic DNAs were extracted using QIAGEN DNeasy tissue kits and sequenced using the Oxford Nanopore PromethION sequencer according to NICEM’s commercial process. The raw data were de novo assembled using Flye v2.9-b1768 (Kolmogorov et al., 2019) and polished four times using Racon v1.5.0 (Vaser et al., 2017) and one time using Medaka v1.6.0.1 As a result, a complete genome of 1 contig of 3.6Mb size showing coverage of 675X depth was obtained (GenBank Assembly accession: GCA_022809775). To maintain the same conditions, all genomes were annotated using Prokka version 1.14.6 (Seemann, 2014). Information regarding CDS, rRNA, CRISPR repeat region, tRNA, and tmRNA was obtained from the Prokka output. Genome assembly statistics, such as number of contigs, bases (size), N50, and G + C content, were obtained using the Genome Assembly Annotation Service (GAAS) tool kit. Small subunit (SSU) rRNA sequences of the type strains were obtained from EzBioCloud. The data for strains with unpublished SSU rRNA sequences were directly exported from the annotation file for each strain.

Phylogenetic Analyses

Core gene phylogeny was performed using PhyloPhlAn (Segata et al., 2013) with .faa result files obtained from Prokka. The phylogenomic tree was constructed with default options of 400 universal protein markers (Supplementary Table 2) and the following tools for the internal steps: USEARCH v5.2.32 (Edgar, 2010) for mapping into amino acid databases; MUSCLE v3.6 (Edgar, 2004) for multiple sequence alignment, and FastTree v2.1.10 (Price et al., 2009) with 1,000 bootstraps for phylogenic inference. The genomes of two strains belonging to the phylum Rhodothermaeota were downloaded from NCBI and used as an outgroup. In addition, the results were compared by phylogeny based on the 16S rRNA sequences. The 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree was multiple aligned using ClustalW (Chenna et al., 2003) in MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013), and 1,000 bootstrap iterations were conducted to construct a tree using the neighbor-joining (Saitou and Nei, 1987) and the maximum-likelihood (White, 1982) methods with the Jukes–Cantor model (Jukes and Cantor, 1969) and the maximum-parsimony (Moore et al., 1973) method.

Calculation of Genomic Indices

Average nucleotide identity values were calculated using the OAU (OrthoANI-usearch tool) (Yoon et al., 2017b), and dDDH (digitalDDH, known as isDDH) was calculated using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2013) provided by the DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany). The AAI calculator by Kostas lab (Luo et al., 2014) was employed to compare two genomes written in amino acids with 20% minimum identity and 50 minimum alignments as alignment options. POCP is a comparison of the genomes as an amino acid sequence of two strains using BLASTP. The matched proteins with an E-value less than 10–5, a sequence identity over 40%, and a query cover of over 50% were regarded as conserved proteins. As strains belonging to the same genus share conserved proteins, with at least half of the whole protein, the strains showing a POCP value over 50% can be considered belonging to the same genus. POCP values were calculated as [(C1 + C2)/(T1 + T2)] × 100%, where C1 and C1 represent the conserved number of proteins in the two genomes, respectively; and T1 and T1 represent the total number of proteins in the two genomes being compared, respectively (Qin et al., 2014).

Relative Synonymous Codon Usage Analysis

The open reading frame (ORF) search was performed as a priority to compare codon usage. The ORF finder function of the Sequence Manipulation Suite tool (Stothard, 2000) was used with the bacterial genetic code beginning with only ATG. The obtained ORFs were calculated using the bacterial genetic code for the codon usage function of the same tool. Analysis was conducted only for codons, excluding Met (ATG) and Trp (TGG), which are encoded by only one codon, and stop codons (TAG, TGA, and TAA) that encode no amino acids. A global test between codon bias in each group was conducted using Analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) with R’s vegan package (Oksanen et al., 2013; Gu et al., 2020). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using R’s prcomp formula, and since 93% of the variables could be explained with three principal components, 3D plotting was performed using plot_ly packages (Sievert, 2020). The distance between plots was obtained by introducing the coordinates into Equation 1.

| (1) |

Comparison of Phenotype and Metal Resistance-Related Genes Between Groups

A literature study was conducted on all strains of the Desulfovibrionaceae family to investigate their phenotype. DIAMOND BLASTP was performed on the BacMet v2.0 database to identify metal resistance-related genes. Genes which satisfy the following conditions were searched: E-value lower than 10–5, 70% or more query coverage, and 30% similarity. The relative abundance of metal resistance-related genes was shown as a heatmap for each genome using ggplot2.

Results

Bacterial Strains and Genomes

All genomes (88 genomes) belonging to Desulfovibrionaceae were collected for subsequent analyses, and their basic information is summarized in Supplementary Table 1. A portion of the target genomes originate from host body isolates, including blood, gut, and feces (Moore et al., 1976; Baron et al., 1989; McOrist et al., 1995) but mainly from anaerobic environments such as sludge, mud, wastewater (sulfidic water), oil field, and marine sediment (Baena et al., 1998; Hernandez-Eugenia et al., 2000). Some members of this family have also been isolated from extreme environments, such as permafrost, ocean vent fields (hydrothermal chimneys), and heavy-metal-effected lake sediments (Ramsay et al., 2015; Ryzhmanova et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020). Likewise, their genomic characteristics also showed large variations amongst isolation sources. Genome sizes ranged from 1.41 to 5.77 Mb, and the G + C content varied over a wide range (32.9–69.8 mol%). Genome statistics, such as contig number and N50, and characteristics, such as CDS, rRNA, tRNA, tmRNA, and CRISPR repeat regions, are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 along with the GenBank assembly accession number.

Core Genes Phylogeny

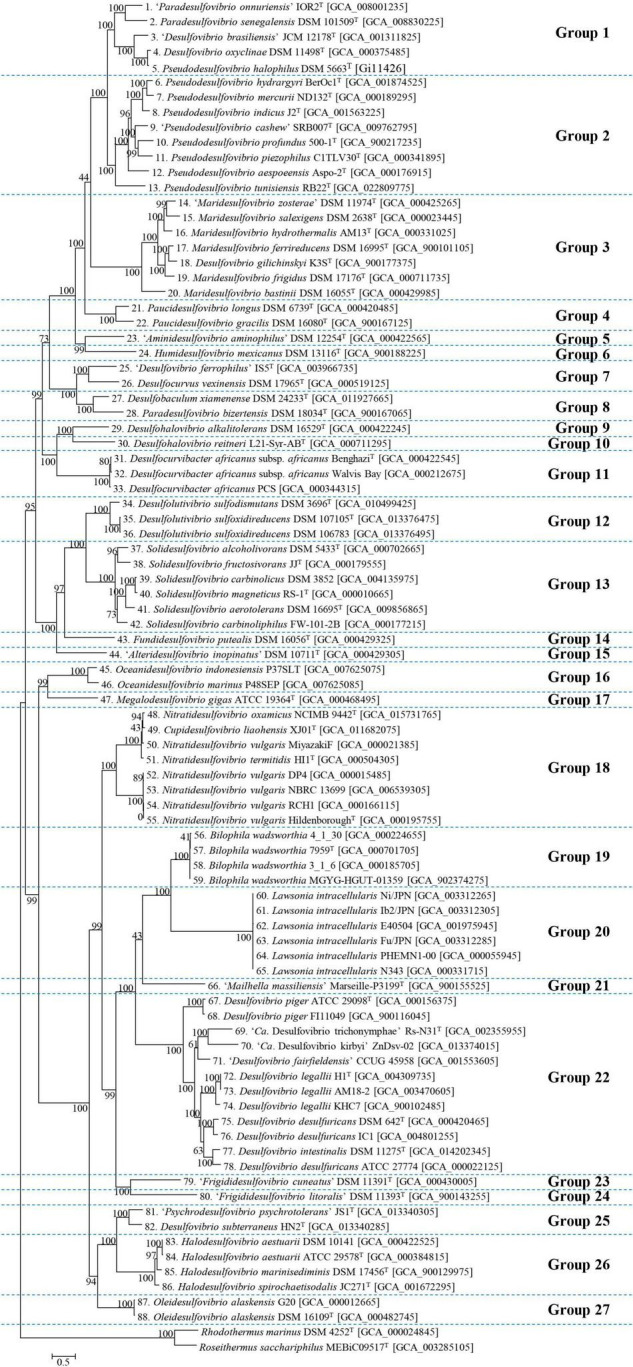

Phylogeny was performed using core genes extracted from previously collected genomes (Figure 1). A quick skim of a classified group with a difference of less than 1.5 distance, referred to the scale bar on the tree, suggested that 88 genomes, excluding the outgroup, could be subdivided into 27 groups. The results of clustering corresponded well with the validly published genera in most group cases. Although the genera constituting groups 5, 15, 21, and 23 are not officially recognized genera, each cluster resulting from those groups matched an individual genus. Group 1 is a mixture of the genera “Paradesulfovibrio” (“Paradesulfovibrio onnuriensis”), Desulfovibrio (“Desulfovibrio brasiliensis” and Desulfovibrio oxyclinae), and Pseudodesulfovibrio (Pseudodesulfovibrio senegalensis, Pseudodesulfovibrio halophilus). Group 8 is a mix of Paradesulfovibrio (Paradesulfovibrio bizertensis) and Desulfobaculum (Desulfobaculum xiamenense). In group 18, Cupidesulfovibrio and Nitratidesulfovibrio genera coexist. Desulfohalovibrio alkalitolerans belonging to group 9, has been classified as belonging to the same genus as Desulfohalovibrio, and with Desulfohalovibrio reitneri belong in group 10. However, as they show sufficient evolutionary distance, it was determined that they should be classified into separate groups. In the same vein, Fdv, from group 23, classified as “Frigididesulfovibrio” can also be proposed as a new genus. Last, group 18 is a cluster of two genera, Nitratidesulfovibrio (Nitratidesulfovibrio oxamicus, Ntd. vulgaris, and Nitratidesulfovibrio termitidis) and Cupidesulfovibrio (Cupidesulfovibrio liaohensis).

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenomic tree of strains belonging to Desulfovibrionacae. Using 400 core gene markers, 88 Desulfovibrionaceae family strains were subdivided into 27 groups. Two type strains belonging to Rhodothermaceae were selected as outgroups. Each number before the scientific name implies the identical organism with the corresponding number at the subsequent analysis. The scale bar represents 5% estimated sequence divergence.

Genome-Based Similarity Indices

Amino-acid identity and POCP are popular examples of genome-based similarity indices for genus delineation. The AAI cut-off value applied for the delineation of genera has a wide range of 60–80% (Konstantinidis and Tiedje, 2005a; Rodriguez-R and Konstantinidis, 2014). In previous studies on the Desulfovibrionaceae family, the AAI value of 60% was adopted to distinguish the genus by checking whether the existing genus satisfies these values (Spring et al., 2019). However, in reality, many taxa do not meet the AAI value criteria above, so it is necessary to verify whether this is an “appropriate AAI criterion that does not violate the monophyly rule” (Orata et al., 2018). Therefore, we devised a method to determine the threshold through clustering and scoring after much consideration. Subjective intervention was avoided by repetitive clustering and evaluation with gradual increment of cut-off parameters to establish unbiased criteria, and not setting strict borders after dividing the genus first. As the AAI cut-off value applied for each taxon varied, a Python script was written to objectively evaluate various thresholds and establish the criteria. This Python script automatically iterates clustering work and evaluates its result to determine an optimum threshold between 60.0 and 80.0. In the clustering step, threshold-based clustering was performed using the given pairwise AAI matrix (Supplementary Table 3). In the scoring step, inclusion of a member in multiple clusters was heavily penalized, whereas the single member group received relatively small point deductions. When the scoring is complete, the threshold is raised by 0.01 and the steps are repeated until the threshold reaches 80.00 (Supplementary Figure 1). For example, if there are three genomes A, B, and C, and A shows similarity above the given threshold with B and C, respectively, but B and C show similarity below the threshold with each other, Three clusters are created: [A, B, C], [A, B], and [A,C]. At this time, since A belongs to these three clusters, a large deduction is given. In order to distinguish the penalty given to the singleton member and the penalty given for overlapping clusters, the large deduction was given more than the total number of genome used. An executable file for Windows is available from the following repository: https://github.com/PMKYU98/monophyly_cutoff. Subsequently, the threshold that finally obtained the maximum score was set as the optimal AAI value. Therefore, there were five AAI threshold ranges calculated as possible thresholds (63.43 ± 0.01, 76.33 ± 0.23, 76.99 ± 0.17, 78.34 ± 0.11, and 78.50 ± 0.01). The threshold 63.43 ± 0.01 was determined to be the best, and when these values were set as cut-off values, it was confirmed that each genome belonged to one of the 27 independent groups without re-occurrence in multiple groups. These 27 groups matched the 27 groups abstracted in the previous phylogenomic tree. The second-best range, 76.33 ± 0.23, formed 49 groups, but an excessive number of unary groups occurred. Therefore, we selected 63.43 ± 0.01 as a promising maximum score, which is in the range of the recommended AAI threshold to classify the genus (Rodriguez-R and Konstantinidis, 2014), but slightly higher than the value used by Spring et al. (2019).

POCP played the role of an auxiliary criterion besides the AAI value, and the value for genera delineation was set at 50% (Qin et al., 2014). However, when plotting the AAI and POCP values between genomes (Supplementary Figure 2), 50% POCP values did not correspond with the 63.43 ± 0.01 AAI cut-off values. Moreover, applying the 50% POCP cut-off violated the monophyly rule for taxon delineation. Previous studies have reported that the POCP cut-off cannot be an appropriate standard for genus delineation in several taxa (Aliyu et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Lopes-Santos et al., 2017; Orata et al., 2018; Wirth and Whitman, 2018). Therefore, it was decided not to adapt the POCP value as a criterion for genus delineation. The AAI and POCP results between each genome are displayed in a heatmap shown in Figure 2, and detailed values can be found in Supplementary Tables 3, 4.

FIGURE 2.

AAI and POCP from pairwise whole-genome comparisons. The values of AAI and POCP were expressed as heatmap. AAI is the lower left triangle indicated in purple color, and POCP is the upper right triangle indicated in cyan color. When the group was divided based on the AAI value alone, it was subdivided into 27 groups, which are separately surrounded by a black square on the figure.

Average nucleotide identity and dDDH are widely used for species delineation because their standard values are defined. If either ANI or dDDH values from the comparison of two genomes are under the cut-off of 95% ANI and 70% dDDH (Colston et al., 2014), they are considered as different species. Among the Nitratidesulfovibrio vulgaris strains belonging to group 18, the Miyazaki F strain should be classified as a different species. Group 22, including Desulfovibrio piger FI11049, Desulfovibrio legallii KHC7, Dsv. desulfuricans IC1 and Dsv. desulfuricans ATCC 27774, should be separated into new species from their type strains. Excluding the strains mentioned above, every other strain met both the ANI and dDDH criteria, and therefore, did not require additional classification. The ANI and dDDH results between each genome are summarized in a heatmap and shown in Supplementary Figure 3. Detailed values are provided in Supplementary Tables 5, 6.

Comparison for Codon Bias

Codon usage can reflect evolutionary processes because it is influenced by the G + C content, replication strand skew, or gene expression (Sharp et al., 2005). Thus, we calculated the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values and measured codon usage bias for each group to verify their evolutionary relationship and clustering (Supplementary Table 7). The RSCU values obtained for each genome were then calculated and plotted. (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 4). ANOSIM was used to observe the similarity in the codon usage bias of each group. The R statistic was 0.678 and the p-value was 0.0001 in the global test result. These figures indicate each genus group has a codon usage bias that differs significantly from other groups, suggesting that the group previously divided at the genus level was sufficiently discriminated. In addition, the PCA using the RSCU values also verified whether they were the same species. Figure 3 shows the distance between them more intuitively in the 3D plot. The numbers in parentheses next to the scientific name in the following statements indicate the label in the figure. Four strains of Ntd. vulgaris, DP4, NBRC 13699, RCH1 and HildenboroughT (52–55), were plotted closely (distance: 0.065 ± 0.035), whereas the other Nitratidesulfovibrio vulgaris strain, Miyazaki F (50), was plotted slightly further away (distance:1.59 ± 0.04). Similarly, Dsv. piger FI11049 (68), Dsv. legallii KHC7 (74), Dsv. desulfuricans IC1 (76), and Dsv. desulfuricans ATCC 27774 (78), which were separated into new species, showed sufficient distance to be separated from strains belonging to the existing group (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

(A) 3D plot of the three major axes generated by principal component analysis (PCA) of the RSCU values. The RSCU of each strain except for the 5 codons of Met, Trp, and Stop codons were plotted after PCA analysis. In this scatter plot, the same color indicates the same genus and the label of each dot can be found in the accompanying.html file. (B) The distance on the PCA plot between the existing group and the strain to be reported as a novel species. 50, Ntd. vulgaris Miyazaki F; 52, Ntd. vulgaris DP4; 53, Ntd. vulgaris NBRC 13699; 54, Ntd. vulgaris RCH1; 55, Ntd. vulgaris HildenboroughT; 67, Dsv. piger ATCC 29098T; 68, Dsv. piger FI11049; 72, Dsv. legallii H1T; 73, Dsv. legallii AM18-2; 74, Dsv. legallii KHC7; 75, Dsv. desulfuricans DSM 642T; 76, Dsv. desulfuricans IC1; 78, Dsv. desulfuricans ATCC 27774.

Phylogenetic Analysis Based on 16S rRNA Sequence

Based on the previous analysis, 88 genomes were divided into 27 genera. During the process, two new genera were added and the possibility of six new species was confirmed. However, since there are many species in the Desulfovibrionaceae family without identified genome sequences, extended phylogenetic analysis using 16S rRNA sequence had to be performed. For this, type strains corresponding to all species and subspecies of taxa registered in the Ez-taxon DB were listed together. To compare with the previous core gene phylogenetic tree, 16S rRNA sequences of strains used for genome analysis were also added. With strains not registered with the 16S rRNA sequence, the sequence was directly extracted from the annotation results. The results are summarized in Figure 4 (illustrated as a mirror image; the left side indicates previously published taxa names, and the right side indicates newly reorganized taxa names), which implies that most of the type strains belonging to Desulfovibrionaceae are well grouped according to new classification groups, as determined by our analysis. Psd. tunisiensis RB22T belonged to the Pseudodesulfovibrio group in the phylogenetic analysis using the genome sequence. Still, it was classified to the Salidesulfovibrio group in analysis using the 16S rRNA sequence. Dsv. cavernae H1MT, which was grouped with Dhv. reitneri L21-Syr-ABT, appears to be far enough to be classified as a different genus. However, as reclassification using the genome sequence was impossible, the status of this species remains to be investigated.

FIGURE 4.

Reclassification of the Desulfovibrionaceae by 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity inferred by genomic tree. This figure includes mirror image. Left sided tree is before reclassifications, Right sided tree is after reclassifications. Purple colored label, rearrangement through this study; Red colored label, proposed as a new genus; Green colored label, which has the potential to be newly classified, but requires further researches because it cannot be achived at this moment: lack of detailed phenotypic characterization or lack of available genome sequence or lack of available culture in two public culture collections. The tree is based on the Jukes & Cantor distances model and the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstraps. Nodes with branch support > = 70% recovered by the three algorithms (the neighbor joining, the maximum-likelihood, and the maximum-parsimony algorithm) were indicated with •; Nodes recovered by the three methods but with < 70% bootstrap values were indicated with ○° ; Nodes recovered by two of the above methods were indicated with °.

Defining Phenotype and Genotype Characteristics for Each Group

To define the characteristics of the newly classified groups, a literature search was conducted on the characteristics of the phenotype for each strain. The information obtained is summarized in Table 1 by group (genus). Most show morphology in the form of curved rods (vibrio) and have motility with a single polar flagellum. Paucidesulfovibrio and Desulfovibrio include members of the spirillum type and Desulfohalovibrio, Oceanidesulfovibrio, and Nitratidesulfovibrio include sigmoid types, inferring that one genus can show various morphologies, as well as vibrio. Regarding growth conditions, the characteristics of each group were more pronounced. Particularly, depending on whether the taxa comprised terrestrial-derived species or marine-derived species, they either did not require salt or demanded a NaCl concentration of 2% or more for optimal growth. In addition, the newly classified genera, Alkalidesulfovibrio, require an optimal pH of higher than 8, which is higher than that required by other genera (generally pH 7). Regarding the G + C content, the difference between the maximum and minimum values in each group of Frigididesulfovibrio, Pseudodesulfovibrio, Desulfocurvus, Desulfobaculum, and Desulfovibrio were 16.6, 13.9, 13.7, 11.3, and 10.6, respectively, showing a difference of over 10 mol%, whereas in other groups, the gap was only around 5 mol%.

TABLE 1.

Phenotype and genotype information of the genera of the family Desulfovibrionaceae.

| Genus | Alkalidesulfovibrio | “Alteridesulfovibrio” | “Aminidesulfovibrio” | Bilophila | Desulfobaculum | Desulfocurvibacter | Desulfocurvus | Desulfohalovibrio | Desulfolutivibrio | |

| Morphology | Vibrio | Vibrio | Vibrio | Pleomorphic rod with swollen ends | v (Rod or Vibrio) | Vibrio | v (Rod or Vibrio) | v (Sigmoid or Vibrio) | Vibrio | |

| Flagellation | Single polar | Single polar | Single polar | – | Single polar | Lophotrichous | Single polar | Single polar or Monopolar bitrichous | Single polar | |

| Motility | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | |

| G + C content (genome) | 64.5 | 49.1 | 66.2 | 59.2–59.3 | 52.3–63.6 | 61.1–61.4 | 56.0–69.7 | 65.5 | 63.5–64.1 | |

| Respiration Quinone | MK-7 | Nr | Nr | Nr | MK-7a | MK-7b | Nr | MK-7/MK-6c | MK-7 | |

| pH range (Opt.) | 6.9–9.9 (9.0–9.4) | 5.0–8.0 (6.9–7.2) | 6.7–8.0 (7.5) | Nr | 6.0–8.1 (7.0–7.6) | 6.3–7.7 (7.0) | Nr (6.9–7.1) | 5.5–8.5 (7.5) | 6.5–8.5 (6.5–7.3) | |

| Temp. range (Opt.) oC | 16–47 (43) | 15–42 (30) | 25–40 (35) | Nr (35–37) | 15–42 (35–40) | 20–40 (37) | Nr (37–40) | 20–48 (37–40) | 15–45 (35–37) | |

| Salinity. range (Opt.)% | 0.085–0.7 (0.13) | 0.5–2.0 (1.0) | 0–2.0 (0.05–0.75) | Nr | 0–12.5 (0.5–2.5) | 0–4.25 (0–1.0) | 0–5.0 (0.2) | 0.7–18.0 (4.0–6.0) | 0.1–2.0 (0.1–0.7) | |

| Fermentative growth | + | – | + | Nr | v+ | – | + | + | Nr | |

| Major electron donors | All | H2†, Formate†, Lactate, Pyruvate |

H2‡, Formate‡, Ethanol, Lactate, Pyruvate, Fumarate, Malate, Sugars | Formate‡, Ethanol‡, Lactate, Pyruvate, Amino acids | Pyruvate | H2†, Lactate, Pyruvate | H2†, Formate†, Ethanol, Lactate, Pyruvate |

Formate‡, Lactate, Pyruvate |

Formate†, Lactate, Pyruvate, Ethanol | H2‡, Ethanol, Lactate |

| Most | Fumarate, Succinate, Malate, Cysteine | H2† | ||||||||

| Some | C2–C4 alcohols | Iron | H2†, C1 and C3-C5 alcohols, Fumarate, Succinate, Malate, Glycerol | Formate‡ | ||||||

| Major electron acceptors | All | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate | Nitrate | Sulfate, Sulfite | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate, Sulfur(w) | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate |

| Most | Thiosulfate, Fumarate | |||||||||

| Some | Sulfur | Nitrate | DMSO | |||||||

| Isolation source | Metal coupon in corroison monitoring reactor in District heating plant |

Marine sediment | Wastewater | Intra-abdominal specimen | Marine sediment, solar saltern |

Marine sediment, well water | Deep ground water, marine sediment, wastewater treatment reactor |

Microbial mat of hypersaline lake, deep subsurface | Sewage sludge, freshwater mud | |

| References | Abildgaard et al., 2006 | Reichenbecher and Schink, 1997 | Baena et al., 1998 | Baron et al., 1989 | Haouari et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2012; Tsu et al., 1998 | Brown et al., 2011; Campbell et al., 1966; Spring et al., 2019; Castañeda-Carrión et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2011 | Klouche et al., 2009; Hamdi et al., 2013; Dinh et al., 2004 | Spring et al., 2019; Sass and Cypionka, 2004 | Thiel et al., 2020; Bak and Pfennig, 1987 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Genus | Desulfovibrio | “Frigididesulfovibrio” | Fundidesulfovibrio | Halodesulfovibrio | Humidesulfovibrio | Lawsonia | Macrodesulfovibrio | “Mailhella” | Maridesulfovibrio | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Morphology | v (Rod or sprillum or Vibrio) | Vibrio | Vibrio | Vibrio | Vibrio | Vibrio | v (Rod or vibrio) | Rod | v (Rod or Vibrio) | |

| Flagellation | Single polar | Single polar | Single polar | Single polar | Single polar | – | Single polar | Nr | Single polar or Monopolar bitrichous | |

| Motility | v+ | + | + | + | v+ | – | + | – | + | |

| G + C content (genome) | 53.6–64.2 | 36.9–53.5 | 62.8 | 45.0–46.2 | 65.0–65.6 | 32.9–33.1 | 54.6–59.5∨ | 59.1 | 41.8–47.1 | |

| Respiration Quinone | MK-6d | Nr | MK-6(H2)e | MK-6f, MK-6(H2)g | MK-6(H2) | Nr | Nr | Nr | MK-6(H2)h | |

| pH range (Opt.) | 4.9–9.0 (7.0–7.5) | Nr | 6.2–8.0 (7.0–7.1) | 6.5–8.5 (7.0–8.0) | 6.0–8.2 (6.5–7.2) | Nr | 5.5–8.5 (7.5–7.9) | Nr | 5.2–8.5 (5.8–7.8) | |

| Temp. range (Opt.) oC | 10–45 (28–37) | 0–33 (28) | 20–40 (30–35) | 10–40 (20–37) | 2–40 (24–37) | Nr (35–37) | 15–45 (35–37) | Nr | 0–50 (19–40) | |

| Salinity. range (Opt.)% | 0–3.0 (0–0.5) | 0.25 (Nr) | 0–6.0 (0–1.0) | 0.05–6.0 (2.0–3.5) | 0–2.0 (0–0.2) | Nr | 0.2–8.0 (0.2–3.0) | Nr | 0–12.0 (1.0–4.0) | |

| Fermentative growth | v+ | + | + | + | v+ | Nr | + | Nr | v+ | |

| Major electron donors | All | H2‡, Ethanol, Lactate, Pyruvate | H2‡, Formate‡, Lactate, Pyruvate, Fumarate | H2†, Ethanol, C4 alcohols, Lactate, Pyruvate | Formate‡, Lactate, Pyruvate, Fumarate, Malate | H2†, Formate†, Lactate, Pyruvate |

Nr | H2‡ Lactate, Pyruvate | Nr | Formate†, Lactate, Pyruvate, |

| Most | Fumarate, Succinate | H2‡, Glycerol, Succinate | Ethanol | H2†, Ethanol, Fumarate | ||||||

| Some | Formate‡, C3-C4 alcohols, Malate, Aromatic aldehydes, Alanine | Ethanol, Malate | C3 alcohols, C4–C5 fatty acids, Fumarate, Malate, Butyrate | Ethanol, C3 alcohols, Amino acids, Sugars | Fumarate, Succinate, Malate, Amino acids, | Formate‡, Ethanol, C3–C4 alcohols, Glycerol, Fumarate, Cysteine | Glycerol, C3–C4 alcohols, Succinate, Malate†, Amino acids, Sugars | |||

| Major electron acceptors | All | Sulfate, Thiosulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate, Sulfur | Sulfate, Thiosulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate, Sulfur, DMSO |

Nr | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate | Sulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate |

| Most | Sulfite | Taurine, Fumarate | ||||||||

| Some | Sulfur, Nitrate, Fumarate, Metal ions# | Sulfite, Fumarate | Fumarate | Sulfur | Sulfur, Fumarate | |||||

| Isolation source | Hindgut of termite, rumen of a sheep, human faeces and blood, tar and sand mix, anaerobic sludge | Littoral sediment | Well water, sewage sludge | Anoxic sea sediment, sea water, soil | Anaerobic sludge of cheese wastewater, permafrost, sediment |

Intestines of animals, intracellular parasite | Thermal spring, lagoon sediment | Human faeces | Saline and freshwater lake, sediment, hydrothermal chimney, seagrass, permafrost, deep subsurface oil well |

|

| References | Loubinoux et al., 2002; Zellner et al., 1989; Jyothsna et al., 2008; Thabet et al., 2010 | Sass et al., 1998 | Basso et al., 2005; Suzuki et al., 2010 | Stüven, 1960; Postgate and Campbell, 1966; Finster and Kjeldsen, 2010; Shivani et al., 2017; Takii et al., 2008 | Hernandez-Eugenia et al., 2000; Pecheritsyna et al., 2012; Sass et al., 2009 | McOrist et al., 1995 | Fadhlaoui et al., 2015; Esnault et al., 1988 | Ndongo et al., 2017 | Magot et al., 2004; Nielsen et al., 1999; Alazard et al., 2003; Postgate and Campbell, 1966; Ben Ali Gam et al., 2018; Ryzhmanova et al., 2019; Vandieken et al., 2006; Sattley and Madigan, 2010 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Genus | Megalodesulfovibrio | Nitratidesulfovibrio | Oceanidesulfovibrio | Oleidesulfovibrio | Paucidesulfovibrio | Pseudodesulfovibrio | Psychrodesulfovibrio | Salidesulfovibrio | Solidesulfovibrio | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Morphology | Vibrio | v (Sigmoid or Vibrio) | v (Sigmoid or Vibrio) | Vibrio | v (Rod or vibrio or spirillum) | Vibrio | Vibrio | v (Rod or Vibrio) | v (Rod or Vibrio) | |

| Flagellation | Single polar | Single polar or Monotrichous polar | Single polar | Single polar | Single polar | Single polar or peritrichous | Single polar | v (Negative or Single polar) | Single polar | |

| Motility | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | v+ | |

| G + C content (genome) | 63.0–63.3 | 63.2–67.1 | 60.4–62.4 | 57.8–64.1 | 58.4–63.6 | 49.9–65.2 | 56.7–59.3 | 58.1–61.0 | 61.6–66.5 | |

| Respiration Quinone | MK-6i | Nr | Nr | Nr | Nr | MK-6(H2)j | MK-6(H2)k | Nr | MK-6l, MK-7(H2)m | |

| pH range (Opt.) | 6.5–8.5 (7.2–7.4) | 5.5–9.0 (6.6–7.4) | 6.4–8.5 (6.9–7.3) | 5.0–10.0 (7.0–7.5) | 5.4–8.8 (6.8–7.4) | 4.5–9.9 (6.5–7.5) | 6.0–10.0 (7.2–9.0) | 4.5–9.0 (6.5–7.6) | 5.3–8.7 (6.5–7.3) | |

| Temp. range (Opt.) oC | 10–45 (30–36) | 16–50 (35–37) | 10–50 (30–37) | 10–45 (37) | 10–50 (35–40) | 4–65 (25–35) | 10–50 (28–35) | 15–45 (30–40) | 3–50 (29–38) | |

| Salinity. range (Opt.)% | 0–10 (0) | 0–5.0 (0–0.1) | 0–17.0 (5.0–6.0) | 0–10.0 (2.5–5.0) | 0–12.0 (1.0–6.0) | 0–10.0 (0.6–8.0) | 0–4.0 (0–0.5) | 0.5–22.5 (3.0–10.0) | 0–5.0 (0–1.0) | |

| Fermentative growth | + | + | + | v | v– | + | + | v+ | + | |

| Major electron donors | All | H2†, Formate†, Lactate, Pyruvate, Fumarate, Succinate, Malate | Lactate, Pyruvate | H2‡, Formate‡, Ethanol, Lactate, Pyruvate, Fumarate, Succinate, Malate, Fructose | Formate‡, Ethanol, Glycerol, Lactate, Pyruvate, Fumarate, Malate | H2‡, Formate‡, Lactate, Pyruvate | Lactate | Ethanol, Lactate, Pyruvate, Succinate, Malate | Lactate, Pyruvate | Ethanol, Lactate, Pyruvate, Fumarate |

| Most | H2†, Formate†, Ethanol, Fumarate, Malate, Organic acids | H2†, Pyruvate, Fumarate, Malate | H2†, Formate† | H2‡, Formate‡, Glycerol, C3–C5 alcohols, Malate | ||||||

| Some | Ethanol, C3–C5 alcohols, Glycerol | C1 and C4 alcohols, Sugars | C4 alcohols | Succinate, Ethanol, C4 alcohols | Formate†, Fatty acids∧, Ethanol∧, C1 and C3–C4 alcohols, Succinate, Amino acid | H2†, Formate†, C4 alcohols, Fumarate, Cysteine | Ethanol, Glycerol, C1 and C3–C4 alcohols, Fumarate, Succinate, Malate, Amino acids |

C1 alcohols‡, Succinate | ||

| Major electron acceptors | All | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate, Sulfur | Sulfate, Sulfite | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate, Sulfur |

Sulfate, Sulfite Thiosulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate, Sulfur |

Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate | Sulfate | Sulfate, Sulfite, Thiosulfate | Sulfate, Thiosulfate |

| Most | Thiosulfate | Fumarate | Sulfur | Sulfite, Sulfur | ||||||

| Some | Fumarate, Haloaromatic compounds | Sulfur, Iron(III), Nitrate, Nitrite, Oxygen, Fumarate | Fumarate | Fumarate | Sulfur, Fe(III), Nitrate, Nitrite, DMSO, Fumarate | Sulfite, Thiosulfate, Fe(III), Mn(IV), DMSO, Fumarate, AQDS | Fe(III), DMSO, Oxygen, Fumarate | Fumarate, Malate | ||

| Isolation source | Water, wastewater from a zinc smelter | Heavy metal impacted sediment, uranium mining waste piles, hindgut of a termite, degraded paddy field, oilfield fluids, chicken feed | Sea water from oilfield, water from oil pipeline | Oil field | Oil field | Marine sediment, deep subsurface, ground water |

Mud and ice, deep sea surface sediment | Marine sediment, microbial mat in saline lake, oil refinery plant wastewater, dolomite |

Waste water, sulfide-rich sediment, ricefield soil, contaminated ground water |

|

| References | Le Gall and Dragoni, 1966; Morais-Silva et al., 2014; Van Houten et al., 2009 | Trinkerl et al., 1990; Aketagawa et al., 1985; Yagi, 1969; Ogata and Yagi, 1986; Ozawa et al., 2000; López-Cortés et al., 2006; Wan et al., 2021; Redburn and Patel, 1994; Voordouw, 2002; Heidelberg et al., 2004 | Feio et al., 1998; Thabet et al., 2007; Tardy-Jacquenod et al., 1996 | Dang et al., 1996; Feio et al., 2004 | Magot et al., 2004; Miranda-Tello et al., 2003; Magot et al., 1992 |

Ranchou-Peyruse et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2000; Cao et al., 2016; Suzuki et al., 2010; Motamedi and Pedersen, 1998; Bale et al., 1997; Khelaifia et al., 2011 Ben Ali Gam et al., 2009 |

Jyothsna et al., 2008 | Kim et al., 2020; Thioye et al., 2017; Warthmann et al., 2005; Krekeler et al., 1997; Caumette et al., 1991 | Nanninga and Gottschal, 1987; Sakaguchi et al., 2002; Ouattara et al., 1999; Mogensen et al., 2005; Ramsay et al., 2015; Allen et al., 2008; Qatibi et al., 1991; Vainshtein et al., 1992; Ollivier et al., 1988; Chamkh et al., 2009 | |

†: Require acetate or yeast extract.

Nr: Not reported.

‡: Require acetate.

Bold type: predominant characteristic.

∧: Require 2-chlorophenol.

v: variable.

∨: G + C content measured based on HPLC.

v+: variable but positive is predominant.

#: only in sulfate-free conditions.

v-: variable but negative is predominant.

+ : positive.

(w): weak activity.

-: negative.

a: Desulfobaculum xiamenense.

b: Desulfocurvibacter africanus benghazi.

c: Desulfohalovibrio reitneri.

d: Desulfovibrio piger, Desulfovibrio legallii.

e: Fundidesulfovibrio butyratiphilus.

f: Halodesulfovibrio aestuarii, Halodesulfovibrio oceani, Halodesulfovibrio spirochaetisodalis.

g: Halodesulfovibrio marinisediminis.

h: Maridiesulfovibrio gilichinskyi.

i: Megalodesulfovibrio gigas.

j: Pseudodesulfovibrio portus.

k: Psychrodesulfovibrio subterraneus.

l: Solidesulfovibrio alcoholivorans, Solidesulfovibrio fructosivorans.

m: Solidesulfovibrio magneticus.

Comparison of Metal Resistance-Related Gene Abundance Between Groups

Most of the Desulfovibrionaceae are isolated from habitats with high metal concentrations (Supplementary Table 1). This inspires interest in the search for metal resistance genes in the Desulfovibrionaceae family. Most species belonging to the family exhibit metal resistance by forming metal-sulfide precipitates, resulting from sulfate reduction. Besides forming metal-sulfide precipitates, several mechanisms are required for metal resistance, including import system regulation, efflux system, extracellular barrier, and reduction. Because many previous studies explored the genes related to sulfate reduction in Desulfovibrionaceae taxa, we focused on other metal resistance genes. Through this analysis, we aimed to explore species with the potential to show metal resistance, and to determine differences between species showing resistance potential and species that do not. The result of PCA of relative abundance data indicates significantly different patterns between each group (Supplementary Figure 5). Although not all species were investigated, obvious trends can be observed within the data. While most Desulfovibrionaceae family members display many metal resistance-related genes (Figure 5), several strains of the genus Desulfovibrio, Lawsonia, Bilophila, and “Mailhella” have low level gene abundances of metal import system regulators, such as copR and corR. They were commonly isolated from the biotic environment (intestine, feces, and blood). Considering that other strains were isolated from environments where metal elements are easily accessible (hydrothermal vent field, heavy metal affected sediment, aquifer, and mud), we estimate that the environmental condition of the habitat is reflected. Conversely, groups under the monophyly are adjacent in a PCA 3D plot (Supplementary Figure 5), which implies that gene abundance patterns of evolutionarily related species show a relative resemblance. Although the analysis was limited to species with identified genome sequences, we observed a distinction between each genus. Regarding Solidesulfovibrio and Desulfovibrio, the abundance of the multidrug efflux system is greater than other genera. The gene abundance related to arsenate methylation was relatively high in the genera Solidesulfovibrio, Pseudodesulfovibrio, Desulfolutivibrio, and Desulfovibrio. The mercury reductase gene, merA, displayed great abundance in the genera Maridesulfovibrio, Desulfocurvibacter, “Mailhella”, Desulfovibrio, and Bilophila (refer to Supplementary Table 8 for details).

FIGURE 5.

Heatmap of metal related genes. This figure verifies that there is a distinguishable difference in pattern of metal resistance related genes between each group.

Discussion and Conclusion

The literature shows several gaps in knowledge regarding the current taxonomy of the family Desulfovibrionaceae. Therefore, this study reclassified the mis-classified taxa. In this process, the entire species was reclassified and expanded to the type strain of the species without genome sequencing. According to previous analysis, a significant number of taxa require classification. However, to propose a new taxon or to change an existing taxon, Rule 30-3b of the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (ICNP) must be followed (Parker et al., 2019), it indicates that the type strain must be deposited into two publicly recognized public culture collections. The classification cannot be ideally completed because some taxa of Desulfovibrionaceae do not meet the mentioned condition due to deposits remaining in only one culture collection or loss of resources (Dsv. legallii KHC7, Dsv. desulfuricans IC1, Dsv. piger FI11049, Dsv. litorals DSM 11393, “Dsv. cavernae” H1M, “Dsv. ferrophilus” IS5, “Dsv. lacusfryxellense” FSRs, “Dsv. dechloracetivorans” SF3, “Dsv. oxyclinae” P1B), while some others lack the complete phenotypic description and chemotaxonomic characterization required to be proposed as a new species (Dsv. desulfuricans ATCC 27774 and Ntd. vulgaris Miyazaki F), which are the common limitations shared with previous research (Galushko and Kuever, 2020a; Waite et al., 2020). Despite the unclear distinction between Oceanidesulfovibrio and Macrodesulfovibrio in phylogeny based on the 16S rRNA sequence, this study with AAI-based criteria could not confirm that Oceanidesulfovibrio and Macrodesulfovibrio should be reorganized into the same genera (Figure 1, 4) due to the lack of reported genomes of strains belonging to those groups. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a classification study applying the AAI classification standard value suggested when the genome of any type strain belonging to Macrodesulfovibrio is reported. In the case of Pseudodesulfovibrio tunisiensis, 16S rRNA phylogeny showed that the bacteria clearly belong to the Salidesulfovibrio group, but genome phylogeny showed that it belongs to the Pseudodesulfovibrio group. Marixanthomonas spongiae HN-E44T has an AAI value of 85.2% with Marixanthomonas ophiurae JCM 14121T. Similarly, AAI and 16S rRNA sequence similarity analysis results conflict also in the case of Marixanthomonas spongiae HN-E44T and Marixanthomonas ophiurae JCM 14121T. Two bacteria have an AAI value of 85.2%, and this exceeds the AAI criteria for genus delineation of Flavobacteriaceae. However, they showed only a 16S rRNA sequence similarity of 93.6%, which is lower than the minimum identity value of 94.9 ± 0.4% to guarantee the circumscription of a single genus (Yarza et al., 2008). This inconsistency is unaccountable yet, but several possibilities can be discussed. An introduction of an external 16S rRNA sequence might be charge of this discrepancy. However, the three 16S rRNA sequences from Pseudodesulfovibrio tunisiensis were highly similar, so this possibility should be excluded. Another possibility is that the evolutionary rate of the rRNA sequence and the genome did not match. It can happen when a large amount of external functional genes are introduced into the genome through various mechanisms, including horizontal gene transfer. This hypothesis is supported by the vast G + C content range of the Pseudodesulfovibrio group from 49.9 to 65.2.

Finally, two novel genera were proposed and the possibility of five independent species was confirmed. In addition, nine species were reclassified into different genera. According to rule 23a of the ICNP, “Each taxon above species, up to and including order, with a given circumscription, position, and rank can bear only one correct name, that is, the earliest that is in accordance with the rules of this code.” Therefore, for group 18, where Nitratidesulfovibrio and Cupidesulfovibrio collided, Nitratidesulfovibrio was established as the genus name of the group. In the same context, Paradesulfovibrio bizertensis of group 8 belongs to the same genus as Desulfobaculum xiamenense and is corrected as Desulfobaculum bizertensis. Despite the vacancy in the genus Paradesulfovibrio, group 1 deserves proposal as a new genus, and because they are of marine origin, we propose a new genus called Salidesulfovibrio.

From this study, objectivity and accuracy were obtained using indices, such as ANI, dDDH, and AAI, to compare genomic similarity and the classification was not based on phylogenetic analysis alone. As there are no clear standards for classifying the genus in the family Desulfovibrionaceae, an AAI cut-off value that did not incur a member included in multiple clusters for taxon delineation was defined to establish a clear standard. These accurately presented values will serve as a criterion to facilitate classification when new genera are added to this taxon.

Not all strains of the Desulfovibrionaceae family are extremophiles. However, strains belonging to this taxon have been reported to tolerate high heavy metal concentrations, and many are isolated from extreme marine environments such as hypersaline environments, deep sea sediment, and hydrothermal vent fields (with high metal concentration), and extreme terrestrial environments, such as regions contaminated with uranium, oil, and heavy metals. Because we noticed the frequent detection of this group in metal rich conditions, we explored the distribution of metal resistance-related genes through macroscopic in silico analysis. The analysis based on the genomes of Desulfovibrionaceae from the public database alone does not define characteristic of each group, yet it reveals a clear tendency within the given data. Based on taxa isolated from the biotic environment showed relatively low gene abundance and that evolutionarily close taxa were located closely on the PCA plot, it could be inferred that each genus showed a uniquely distinct gene abundance pattern under the influence of both environmental and evolutionary factors.

Taxonomic Reclassifications

Description of Alkalidesulfovibrio gen. nov.

Alkalidesulfovibrio [Al.ka.li.de.sul.fo.vi’.bri.o. N.L. n. alkali (from Arabic article al the; Arabic n. qaliy ashes of saltwort) alkali; N.L. masc. n. Desulfovibrio a bacterial genus; N.L. masc. n. Alkalidesulfovibrio a Desulfovibrio living in alkaline environment].

Cells are vibrio-shaped, 0.5–0.8 × 1.4–1.9 μm. DNA G + C content is 64.5 mol%. Cells are motile by a single polar flagellum. The member of this genus shows anaerobic respiration, but tolerates short exposure to oxygen. Fermentative growth is observed. Sulfate, thiosulfate, and sulfite serve as electron acceptors and are reduced to sulfide. H2/CO2 and formate can serve as an electron donor in the presence of yeast extract or acetate. Thermotolerant, the optimum temperature for growth is 43°C and alkaliphilic, the optimum pH for growth is 9.0–9.4. The major menaquinone is MK-7. Desulfoviridin is present. The type species is Alkalidesulfovibrio alkalitolerans.

Description of Alkalidesulfovibrio alkalitolerans comb. nov.

Basonym: Desulfovibrio alkalitolerans (Abildgaard et al., 2006).

Other synonym: Desulfohalovibrio alkalitolerans (Spring et al., 2019).

The description is the same given by Abildgaard et al. (2006). The type strain is DSM 16529T (= RT2T = JCM 12612T). Genome and 16S rRNA sequence accession number: NZ_ATHI00000000 and AY649785.

Description of Salidesulfovibrio gen. nov.

Salidesulfovibrio [Sa.li.de.sul.fo.vi’.bri.o. L. masc. n. sal (gen. salis), salt; N.L. masc. n. Desulfovibrio a bacterial genus; N.L. masc. n. Salidesulfovibrio a Desulfovibrio living in saline environment].

Cells are rod or vibrio shaped, 0.3–0.5 × 1.0–4.0 μm with motility. Lactate and pyruvate are used as electron donors and some members show fermentative growth. When yeast extract and cysteine or acetate are present, H2/CO2 and formate can be used. Sulfate can be reduced to sulfide, and some members can use sulfur and Fe(III) as electron acceptors. Mesophilic, the optimum temperature for growth is 30–40°C and neutrophilic, the optimum pH for growth is 6.5-7.6. The DNA G + C content is 55.8–61.0 mol%. The type species is Salidesulfovibrio onnuriiensis.

Description of Salidesulfovibrio onnuriiensis comb. nov. nom. rev.

Basonym: ‘Paradesulfovibrio onnuriensis’ (Kim et al., 2020).

The description is the same given by Kim et al. (2020). The type strain is IOR2T (= KCTC 15845T = MCCC 1K04559T). Genome and 16S rRNA sequence accession number: CP040751.1 and MK968309.

Description of Salidesulfovibrio brasiliensis comb. nov.

Basonym: ‘Desulfovibrio brasiliensis’ (Warthmann et al., 2005).

The description is the same given by Warthmann et al. (2005). The type strain is JCM 12178T (= DSM 15816T = LVform1T). Genome and 16S rRNA sequence accession number: NZ_BBCB01000000 and AJ544687.

Description of Salidesulfovibrio halophilus comb. nov.

Basonym: Desulfovibrio halophilus (Caumette et al., 1991).

Other synonym: Pseudodesulfovibrio halophilus (Waite et al., 2020).

The description is the same given by Caumette et al. (1991). The type strain is DSM 5663T (= ATCC 51179T = SL8903T). Genome and 16S rRNA sequence accession number: SRX1760576 and X99237.

Description of Salidesulfovibrio senegalensis comb. nov.

Basonym: Desulfovibrio senegalensis (Thioye et al., 2017).

Other synonym: Pseudodesulfovibrio senegalensis (Galushko and Kuever, 2019), ‘Paradesulfovibrio senegalensis’ (Kim et al., 2020).

The description is the same given by Thioye et al. (2017), Galushko and Kuever (2019), and Kim et al. (2020). The type strain is DSM 101509T (= BLaC1T = JCM 31063T). Genome and 16S rRNA sequence accession number: NZ_WAIE00000000 and KT767981.

Emended Description of the Genus Psychrodesulfovibrio Galushko and Kuever, 2020d

Psychrodesulfovibrio [Psy.chro.de.sul.fo.vi’bri.o. Gr. masc. adj. psychros, cold; N.L. masc. n. Desulfovibrio, a bacterial genus; N.L. masc. n. Psychrodesulfovibrio, a Desulfovibrio living in the cold].

Cells are vibrio-shaped. DNA G + C content is 56.7-59.3 mol%. Cells are motile by a single polar flagellum. Strictly anaerobic with respiratory metabolism type. Sulfate serves as an electron acceptor. Succinate, malate, fumarate, pyruvate, lactate, and ethanol serve as electron donors with sulfate. Mesophilic, the optimum temperature for growth is 30-36OC and neutrophilic, the optimum pH for growth is 7.2-9.0. The type species is Psychrodesulfovibrio psychrotolerans.

Description of Psychrodesulfovibrio subterraneus comb. nov.

Basonym: Desulfovibrio subterraneus (Ueno et al., 2021).

The description is the same given by Ueno et al. (2021). The type strain is HN2T (= DSM 101010T = NBRC 112213T). Genome and 16S rRNA sequence accession number: NZ_BLVO00000000 and LC531930.

Description of Desulfobaculum bizertensis comb. nov.

Basonym: Desulfovibrio bizertensis (Haouari et al., 2006).

Other synonym: Paradesulfovibrio bizentensis (Waite et al., 2020).

The description is the same given by Haouari et al. (2006). The type strain is DSM 18034T (= MB3T = NCIMB 14199T). Genome and 16S rRNA sequence accession number: SRX1760595 and DQ422859.

Description of Nitratidesulfovibrio liaohensis comb. nov.

Basonym: Cupidesulfovibrio liaohensis (Wan et al., 2021).

The description is the same given by Wan et al. (2021). The type strain is XJ01T (= DSM 107637T = CGMCC 1.5227T). Genome and 16S rRNA sequence accession number: NZ_VSMK00000000.1 and MK260014.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

M-JP conducted every computational analysis and wrote manuscript. YK and KK designed experiment and instructed manuscript. MP helped programming for data treatment and repetitive calculation process. JY, TN, and Y-RR conducted literature study and organized data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to gratefully thank editor and the two reviewers who shared their insights into Desulfovibrionaceae taxa and led constructive discussions.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by Korea Institute of Ocean Science & Technology (PE99922) and Korea Ministry of Oceans & Fisheries (20170411).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.738205/full#supplementary-material

Repetitive clustering and evaluation. Repetitive clustering and evaluation designed to find an appropriate AAI classification value without inclusion of a member in multiple cluster. Subjective intervention was avoided by repetitive clustering and evaluation with gradual increment of cut-off parameter to establish unbiased criteria, not setting strict borders after dividing the genus first.

Correlation between AAI and POCP. Red dots represent values between inter-genus strains, and blue dots represent values between intra-genus strains. The color of regression equation in the upper left corresponds to the color of each dot.

ANI and dDDH from pairwise whole-genome comparisons. The values of ANI and dDDH were expressed as heatmap. ANI is the lower left triangle indicated in violet color, and dDDH is the upper right triangle indicated in red color. Groups identified as the same species based on ANI and dDDH values are surrounded by black squares.

Comparison of the RSCU data of the 27 groups. This figure verifies that there is a distinguishable difference in codon usage between each group. A line plot showing the average value of RSCU for each group.

PCA results for metal resistance related gene abundance using z-score normalization. This figure verifies that there is a distinguishable difference in pattern of metal resistance related genes between each group.

Isolation information and genomic indices by bacterial strains.

The universal protein markers using for multi locus sequence alignments.

AAI values between genomes.

POCP values between genomes.

ANI values between genomes.

dDDH values between genomes.

RSCU values of each genome.

Relative abundance of metal related genes.

References

- Abildgaard L., Nielsen M. B., Kjeldsen K. U., Ingvorsen K. (2006). Desulfovibrio alkalitolerans sp. nov., a novel alkalitolerant, sulphate-reducing bacterium isolated from district heating water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56 1019–1024. 10.1099/ijs.0.63909-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aketagawa J., Kobayashi K., Ishimoto M. (1985). Purification and properties of thiosulfate reductase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris, Miyazaki F. J. Biochem. 97 1025–1032. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alazard D., Dukan S., Urios A., Verhé F., Bouabida N., Morel F., et al. (2003). Desulfovibrio hydrothermalis sp. nov., a novel sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from hydrothermal vents. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53 173–178. 10.1099/ijs.0.02323-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu H., Lebre P., Blom J., Cowan D., De Maayer P. (2016). Phylogenomic re-assessment of the thermophilic genus Geobacillus. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 39 527–533. 10.1016/j.syapm.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen T. D., Kraus P. F., Lawson P. A., Drake G. R., Balkwill D. L., Tanner R. S. (2008). Desulfovibrio carbinoliphilus sp. nov., a benzyl alcohol-oxidizing, sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from a gas condensate-contaminated aquifer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58 1313–1317. 10.1099/ijs.0.65524-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakaki A., Takeyama H., Tanaka T., Matsunaga T. (2002). “Cadmium recovery by a sulfate-reducing magnetotactic bacterium, Desulfovibrio magneticus RS-1, using magnetic separation,” in Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals, eds Davison B. H., Wyman C. E., Finkelstein M. (Berlin: Springer; ), 833–840. 10.1385/abab:98-100:1-9:833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayangbenro A. S., Olanrewaju O. S., Babalola O. O. (2018). Sulfate-reducing bacteria as an effective tool for sustainable acid mine bioremediation. Front. Microbiol. 9:1986. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena S., Fardeau M.-L., Labat M., Ollivier B., Garcia J.-L., Patel B. (1998). Desulfovibrio aminophilus sp. nov., a novel amino acid degrading and sulfate reducing bacterium from an anaerobic dairy wastewater lagoon. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21 498–504. 10.1016/s0723-2020(98)80061-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak F., Pfennig N. (1987). Chemolithotrophic growth of Desulfovibrio sulfodismutans sp. nov. by disproportionation of inorganic sulfur compounds. Arch. Microbiol. 147 184–189. 10.1007/bf00415282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bale S., Goodman K., Rochelle P. A., Marchesi J. R., Fry J. C., Weightman A. J., et al. (1997). Desulfovibrio profundus sp. nov., a novel barophilic sulfate-reducing bacterium from deep sediment layers in the Japan sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 47 515–521. 10.1099/00207713-47-2-515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barco R., Garrity G., Scott J., Amend J., Nealson K., Emerson D. (2020). A genus definition for bacteria and archaea based on a standard genome relatedness index. MBio 11:e02475-19. 10.1101/392480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron E. J., Summanen P., Downes J., Roberts M. C., Wexler H., Finegold S. M. (1989). Bilophila wadsworthia, gen. nov. and sp. nov., a unique gram-negative anaerobic rod recovered from appendicitis specimens and human faeces. Microbiology 135 3405–3411. 10.1099/00221287-135-12-3405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L., Legall J., Odom J., Peck H., Jr. (1983). Energy coupling to nitrite respiration in the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio gigas. J. Bacteriol. 153 867–871. 10.1128/jb.153.2.867-871.1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso O., Caumette P., Magot M. (2005). Desulfovibrio putealis sp. nov., a novel sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from a deep subsurface aquifer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55 101–104. 10.1099/ijs.0.63303-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ali Gam Z., Thioye A., Cayol J.-L., Joseph M., Fauque G., Labat M. (2018). Characterization of Desulfovibrio salinus sp. nov., a slightly halophilic sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from a saline lake in Tunisia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 68 715–720. 10.1099/ijsem.0.002567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ali Gam Z., Oueslati R., Abdelkafi S., Casalot L., Tholozan J. L., Labat M. (2009). Desulfovibrio tunisiensis sp. nov., a novel weakly halotolerant, sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from exhaust water of a Tunisian oil refinery. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59 1059–1063. 10.1099/ijs.0.000943-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. D., Wall J. D., Kucken A. M., Gilmour C. C., Podar M., Brandt C. C., et al. (2011). Genome sequence of the mercury-methylating and pleomorphic Desulfovibrio africanus strain Walvis Bay. J. Bacteriol. 193 4037–4038. 10.1128/jb.05223-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L. L., Kasprzycki M. A., Postgate J. R. (1966). Desulfovibrio africanus sp. n., a new dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 92 1122–1127. 10.1128/jb.92.4.1122-1127.1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Gayet N., Zeng X., Shao Z., Jebbar M., Alain K. (2016). Pseudodesulfovibrio indicus gen. nov., sp. nov., a piezophilic sulfate-reducing bacterium from the Indian Ocean and reclassification of four species of the genus Desulfovibrio. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66 3904–3911. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda-Carrión I. N., Sheik C. S., Krumholz L. R. (2010). Desulfovibrio africanus subsp. uniflagellum subsp. nov., a sulfate-reducing bacterium from a uranium-contaminated subsurface aquifer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60 880–886. 10.1099/ijs.0.006668-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caumette P., Cohen Y., Matheron R. (1991). Isolation and characterization of Desulfovibrio halophilus sp. nov., a halophilic sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from Solar Lake (Sinai). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 14 33–38. 10.1016/s0723-2020(11)80358-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chamkh F., Spröer C., Lemos P. C., Besson S., El Asli A.-G., Bennisse R., et al. (2009). Desulfovibrio marrakechensis sp. nov., a 1, 4-tyrosol-oxidizing, sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from olive mill wastewater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59 936–942. 10.1099/ijs.0.003822-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenna R., Sugawara H., Koike T., Lopez R., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G., et al. (2003). Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31 3497–3500. 10.1093/nar/gkg500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J., Rainey F. A. (2014). Integrating genomics into the taxonomy and systematics of the Bacteria and Archaea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64 316–324. 10.1099/ijs.0.054171-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colston S. M., Fullmer M. S., Beka L., Lamy B., Gogarten J. P., Graf J. (2014). Bioinformatic genome comparisons for taxonomic and phylogenetic assignments using Aeromonas as a test case. MBio 5:e02136. 10.1128/mbio.02136-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang P. N., Dang T. C. H., Lai T. H., Stan-Lotter H. (1996). Desulfovibrio vietnamensis sp. nov., a halophilic sulfate-reducing bacterium from Vietnamese oil fields. Anaerobe 2 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh H. T., Kuever J., Mußmann M., Hassel A. W., Stratmann M., Widdel F. (2004). Iron corrosion by novel anaerobic microorganisms. Nature 427 829–832. 10.1038/nature02321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26 2460–2461. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnault G., Caumette P., Garcia J.-L. (1988). Characterization of Desulfovibrio giganteus sp. nov., a sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from a brackish coastal lagoon. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 10 147–151. 10.1016/s0723-2020(88)80029-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fadhlaoui K., Hania W. B., Postec A., Fauque G., Hamdi M., Ollivier B., et al. (2015). Characterization of Desulfovibrio biadhensis sp. nov., isolated from a thermal spring. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65 1256–1261. 10.1099/ijs.0.000088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feio M. J., Beech I. B., Carepo M., Lopes J. M., Cheung C. W. S., Franco R., et al. (1998). Isolation and characterization of a novel sulphate-reducing bacterium of the Desulfovibrio genus. Anaerobe 4 117–130. 10.1006/anae.1997.0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feio M. J., Zinkevich V., Beech I. B., Llobet-Brossa E., Eaton P., Schmitt J., et al. (2004). Desulfovibrio alaskensis sp. nov., a sulphate-reducing bacterium from a soured oil reservoir. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54 1747–1752. 10.1099/ijs.0.63118-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finster K. W., Kjeldsen K. U. (2010). Desulfovibrio oceani subsp. oceani sp. nov., subsp. nov. and Desulfovibrio oceani subsp. galateae subsp. nov., novel sulfate-reducing bacteria isolated from the oxygen minimum zone off the coast of Peru. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 97 221–229. 10.1007/s10482-009-9403-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galushko A., Kuever J. (2019). “Pseudodesulfovibrio,” in Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, ed. Whitman W. B. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; ), 1–11. 10.1002/9781118960608.gbm01574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galushko A., Kuever J. (2020b). “Macrodesulfovibrio gen. nov,” in Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, ed. Whitman W. B. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 1–5. 10.1002/9781118960608.gbm01893 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galushko A., Kuever J. (2020c). “Oceanidesulfovibrio gen. nov,” in Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, ed. Whitman W. B. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 1–5. 10.1002/9781118960608.gbm01894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galushko A., Kuever J. (2020d). “Psychrodesulfovibrio gen. nov,” in Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, ed. Whitman W. B. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 1–5. 10.1002/9781118960608.gbm01892 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galushko A., Kuever J. (2020a). “Desulfovibrionaceae,” in Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, ed. Whitman W. B. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 1–13. 10.1002/9781118960608.fbm00199.pub2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goñi-Urriza M., Klopp C., Ranchou-Peyruse M., Ranchou-Peyruse A., Monperrus M., Khalfaoui-Hassani B., et al. (2020). Genome insights of mercury methylation among Desulfovibrio and Pseudodesulfovibrio strains. Res. Microbiol. 171 3–12. 10.1016/j.resmic.2019.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulhen F., Gloter A., Guyot F., Bruschi M. (2006). Cr (VI) detoxification by Desulfovibrio vulgaris strain Hildenborough: microbe–metal interactions studies. Appl. Microbiol. Biotecnhol. 71 892–897. 10.1007/s00253-005-0211-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H., Chu D. K., Peiris M., Poon L. L. (2020). Multivariate analyses of codon usage of SARS-CoV-2 and other betacoronaviruses. Virus Evol. 6:veaa032. 10.1093/ve/veaa032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi O., Hania W. B., Postec A., Bartoli M., Hamdi M., Bouallagui H., et al. (2013). Isolation and characterization of Desulfocurvus thunnarius sp. nov., a sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from an anaerobic sequencing batch reactor treating cooking wastewater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63 4237–4242. 10.1099/ijs.0.051664-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haouari O., Fardeau M.-L., Casalot L., Tholozan J.-L., Hamdi M., Ollivier B. (2006). Isolation of sulfate-reducing bacteria from Tunisian marine sediments and description of Desulfovibrio bizertensis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56 2909–2913. 10.1099/ijs.0.64530-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberg J. F., Seshadri R., Haveman S. A., Hemme C. L., Paulsen I. T., Kolonay J. F., et al. (2004). The genome sequence of the anaerobic, sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Nat. Biotechnol. 22 554–559. 10.1038/nbt959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Eugenia G., Fardeau M.-L., Patel B. K., Macarie H., Garcia J.-L., Ollivier B. (2000). Desulfovibrio mexicanus sp. nov., a Sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from an upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor treating cheese wastewaters. Anaerobe 6 305–312. 10.1006/anae.2000.0354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong O. J., Choi J.-H., Kim I. H., Kim Y.-K., Oh B.-K. (2015). Effective bioremediation of Cadmium (II), nickel (II), and chromium (VI) in a marine environment by using Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 20 937–941. 10.1007/s12257-015-0287-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes T. H., Cantor C. R. (1969). “Evolution of protein molecules,” in Mammalian Protein Metabolism, ed. Munro H. N. (New York, NY: Academic press; ), 21–132. 10.1016/b978-1-4832-3211-9.50009-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Just S., Mondot S., Ecker J., Wegner K., Rath E., Gau L., et al. (2018). The gut microbiota drives the impact of bile acids and fat source in diet on mouse metabolism. Microbiome 6 1–18. 10.1186/s40168-018-0510-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jyothsna T. S., Sasikala C., Ramana C. V. (2008). Desulfovibrio psychrotolerans sp. nov., a psychrotolerant and moderately alkaliphilic sulfate-reducing deltaproteobacterium from the Himalayas. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58 821–825. 10.1099/ijs.0.65402-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller K. L., Wall J. D. (2011). Genetics and molecular biology of the electron flow for sulfate respiration in Desulfovibrio. Front. Microbiol. 2:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller K. L., Rapp-Giles B. J., Semkiw E. S., Porat I., Brown S. D., Wall J. D. (2014). New model for electron flow for sulfate reduction in Desulfovibrio alaskensis G20. Appl. Environ. Microb. 80 855–868. 10.1128/aem.02963-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg W. W., Cadle R., Allen E., Lazrus A., Martell E. (1972). The sulfur cycle. Science 175 587–596. 10.1126/science.175.4022.587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. J., Yang J.-A., Lim J. K., Park M.-J., Yang S.-H., Lee H. S., et al. (2020). Paradesulfovibrio onnuriensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a chemolithoautotrophic sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from the Onnuri vent field of the Indian Ocean and reclassification of Desulfovibrio senegalensis as Paradesulfovibrio senegalensis comb. nov. J. Microbiol. 58 252–259. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klouche N., Basso O., Lascourreges J.-F., Cayol J.-L., Thomas P., Fauque G., et al. (2009). Desulfocurvus vexinensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from a deep subsurface aquifer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59 3100–3104. 10.1099/ijs.0.010363-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluyver A. J., Van Niel C. B. (1936). Prospects for a natural system of classification of bacteria. Zentralbl. Bakter. Par. 94 369–403. 10.2307/j.ctv176g0.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Hasegawa H., Takagi M., Ishimoto M. (1982). Proton translocation associated with sulfite reduction in a sulfate-reducing bacterium, Desulfovibrio vulgaris. FEBS Lett. 142 235–237. 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80142-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov M., Yuan J., Lin Y., Pevzner P. A. (2019). Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37 540–546. 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]