Abstract

Lung disease with diffuse nodules has a broad differential diagnosis. We present a case of childhood papillary thyroid carcinoma with diffuse lung metastases in which the diagnosis was delayed due to fact that the diffuse nodules were considered to be pathognomonic of miliary tuberculosis. Diffuse nodular lung disease in children requires a careful diagnostic approach. The role of multidisciplinary involvement in these rare cases is invaluable.

Keywords: Paediatric oncology, Paediatrics, Respiratory medicine

Background

Lung disease with diffuse nodules has a broad differential diagnosis in children. While infective aetiologies are most common, lung metastases should be considered in the differential diagnosis. We report a case of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) with diffuse ‘miliary’ metastases on chest radiograph (CXR) and CT chest.

Case presentation

A teenage boy was referred with suspected miliary tuberculosis (TB) due to a non-resolving cough, loss of weight, diminished exercise tolerance and diffuse nodular opacities on CXR. He had no exposure to TB or COVID-19. Nor did he travel recently, use electronic cigarettes or have contact with birds. He was born extremely premature (27 weeks gestational age), requiring 3 months of respiratory support (both invasive and non-invasive), after which he had a relatively symptom-free childhood.

On admission, he appeared acute-on-chronically ill. He was tachypnoeic and hypoxic at rest. No digital clubbing or organomegaly was present, but he had palpable cervical lymphadenopathy and a central neck mass. Respiratory examination revealed limited chest expansion and diffuse bilateral crackles.

Investigations

The Mantoux skin test was non-reactive. Sputum GeneXpert and microscopy for acid-fast bacilli were negative. Haematological investigations demonstrated polycythaemia (haemoglobin 16.2 g/L) while the differential white cell count and peripheral smear were unremarkable. Connective tissue screen and HIV serology were negative, inflammatory markers were not raised and normal thyroid function.

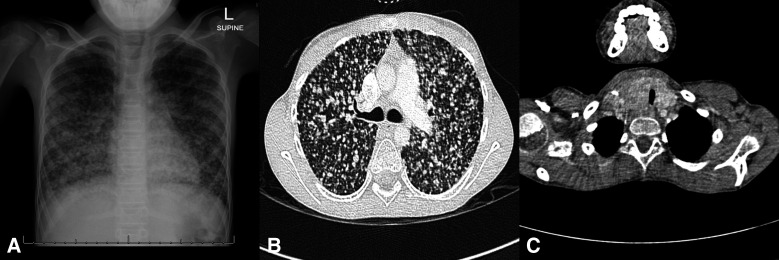

Anteroposterior CXR exhibited countless diffuse pulmonary nodules of varying size with a right paratracheal mass causing visible displacement of the trachea (figure 1A). CT chest confirmed diffuse bilateral nodules with a basal predominance (figure 1B). The right thyroid lobe was enlarged, causing mass effect on the trachea (figure 1C). Pathological lymph nodes were present in the lateral compartment of the neck and the upper mediastinum. Thyroid ultrasound demonstrated a hypoechoic mass with microcalcifications scattered throughout the right thyroid lobe. Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the largest nodule in the right lobe of the thyroid showed typical features of PTC.

Figure 1.

(A) Anteroposterior chest radiograph of the chest demonstrating diffuse, coarse lung nodules of varying size throughout the lung fields. The nodules extend to the lung periphery with a basal predominance and areas of confluence in the basal zones. At the level of the thoracic inlet the trachea is compressed from the right with lateral displacement. There is no evidence of compression of the main-stem bronchi or bronchus intermedius and no perihilar or subcarinal nodes are present. (B) Transverse contrasted CT chest (lung window); widespread, evenly distributed coarse pulmonary nodules of varying size (maximal size 6 mm) extend to the lung periphery. No ventilation defect, hilar or subcarinal lymph nodes are present. (C) transverse contrasted CT (mediastinal window) demonstrating an ill-defined mass in the right lobe of the thyroid with compression and lateral displacement of the tracheal.

Extensive investigation did not reveal any diagnosis other than metastases as a cause of the diffuse lung nodules, howeve, no lung biopsy was performed. Post-treatment WBS I-123, however, showed diffuse irregular pulmonary uptake localising to a bilateral diffuse reticular nodular pattern with basal predominance, suggestive of metastases.

Treatment

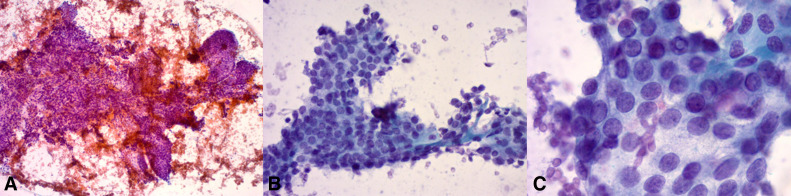

Total thyroidectomy with resection of the right recurrent laryngeal nerve, a right lateral neck dissection with en bloc resection of the internal jugular vein and bilateral central neck dissections was performed. The pathology reported a 36 mm BRAFV600E negative classic type PTC with extrathyroidal extension into the skeletal muscle. Twenty-one out of the 47 lymph nodes showed metastatic cancer (figure 2A–C)

Figure 2.

(A) A low magnification image showing flat sheets with branching comprised of round-oval follicular cells. Papanicolaou stain, ×10. (B) Higher magnification image showing a flat sheet of crowded and overlapping follicular cells with pale chromatin features. Papanicolaou stain, ×40 (C) High magnification demonstrating the fine nuclear chromatin, with inconspicuous nucleoli and occasional intranuclear pseudo (top centre). All these features are consistent with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Papanicolaou stain, ×100.

Due to persistent hypoxia and oxygen dependency, standard treatment with adjuvant radio-active iodine (RAI) was impossible. Therefore, the multikinase inhibitor, sorafenib, was initiated, and his oxygen requirements steadily decreased. Once no longer hypoxic, he received RAI. Thyroglobulin levels and antithyroglubulin antibodies decreased from 14 330 µg/L to 750 ug/L (3.5–77.0 µg/L) and 83 U/mL to 18 U/mL (<115 U/mL), respectively.

We do not have access to routine molecular testing for thyroid cancers at our hospital, due to resource constraints and the unavailability of targeted therapy.

Outcome and follow-up

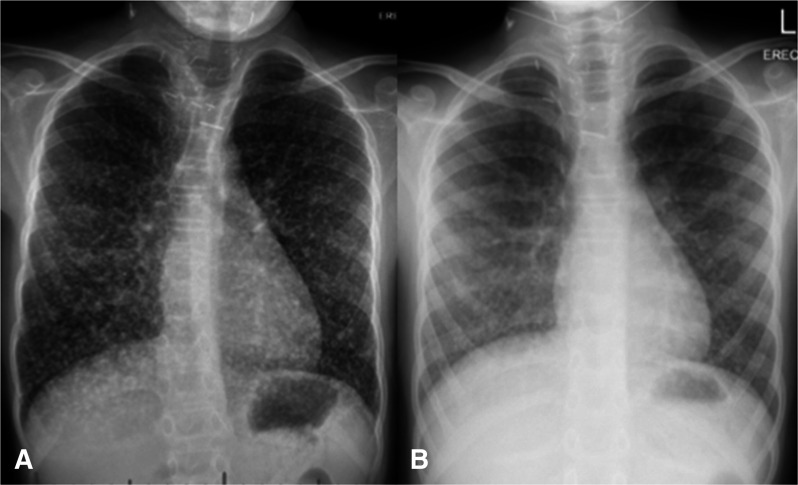

He could maintain oxygen saturation on room air within 4 months postoperatively, and CXR showed gradual improvement with decreased nodule size (figure 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Chest X-ray: Significant improvement of the miliary metastasis picture after the use of sorafenib. (b) Chest X-ray: Postsorafenib and RAI treatment chest X-ray demonstrating near to complete disappearance of the metastasis. RAI, radio-active iodine.

Discussion

Childhood lung disease with parenchymal opacities requires a careful diagnostic approach.1 Infection and environmental exposures, including e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury (EVALI), are leading causes. Infections, including Pneumocystis Jirovecii, cytomegalovirus, fungal infection and military TB, are often associated with immunosuppression.2 In high burden HIV and TB areas, miliary TB and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis have become synonymous with diffuse micronodular lung infiltrates. Nodal airway compression occurs in childhood TB, however, bronchus intermedius and the left main bronchus are most commonly involved, and isolated tracheal compression rarely occurs.3

While uncommon, pulmonary metastases do occur and should be considered in children with pulmonary nodules.4 In contrast to adults, childhood thyroid carcinoma often presents with advanced disease, and lung metastasis regularly occurs.5 Careful examination of chest imaging for mediastinal masses or signs of airway compression is required.

Conclusion

We present a case of childhood PTC with diffuse lung metastases. The diagnosis was delayed due to diffuse nodules being considered pathognomonic of miliary TB. This case demonstrates that diffuse nodular lung disease in children requires a careful diagnostic approach to identify rare causes that require urgent and specific therapy. The role of multidisciplinary involvement in these rare cases are invaluable.

Learning points.

Diffuse lung nodules in children have a broad differential diagnosis.

Metastatic lung disease does occur in children and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of lung nodules.

Miliary tuberculosis (TB) is not the only cause of diffuse micronodular lung disease in TB endemic areas.

Footnotes

Contributors: AG and PG were responsible for the clinical management of the patient. WC was responsible for the surgical management. PS was responsible for the histology. All the authors contributed to the report, reviewed the script and agreed on the content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained from parent(s)/guardian(s)

References

- 1.Bush A, Cunningham S, de Blic J, et al. European protocols for the diagnosis and initial treatment of interstitial lung disease in children. Thorax 2015;70:1078–84. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gie AG, Morrison J, Gie RP, et al. Diagnosing diffuse lung disease in children in a middle-income country: the role of open lung biopsy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017;21:869–74. 10.5588/ijtld.16.0853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goussard P, Gie RP, Kling S, et al. Bronchoscopic assessment of airway involvement in children presenting with clinically significant airway obstruction due to tuberculosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2013;48:1000–7. 10.1002/ppul.22747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva CT, Amaral JG, Moineddin R, et al. CT characteristics of lung nodules present at diagnosis of extrapulmonary malignancy in children. Am J Roentgenol 2010;194:772–8. 10.2214/AJR.09.2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nies M, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Bassett RL, et al. Distant metastases from childhood differentiated thyroid carcinoma: clinical course and mutational landscape. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021;106:1683–97. 10.1210/clinem/dgaa935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]