Abstract

COVID-19 mainly causes a lower respiratory tract illness, meaning there has been great interest in the chest and lung radiological findings seen during the course of the disease. Most of this interest has centred around the computed tomographic findings. Most commonly, computed tomographic images report ground-glass opacities but a less common finding, and potential complication associated with COVID-19, is pneumatocele formation. In this case series, we describe the presentation and management of three patients with large pneumatoceles that developed during the recovery phase of COVID-19. A conservative approach is most recommended, with surgical intervention reserved for complicated cases that cause cardiorespiratory compromise.

Keywords: Pneumatocele, COVID-19, pneumothorax, thorax

Introduction

The radiographic features of the chest and lungs during the course of COVID-19 infection have been of great interest, mainly centring around computed tomographic (CT) imaging, which is thought to yield the best diagnostic benefit. Most studies of CT chest findings have shown bilateral involvement with ground-glass opacity and consolidation the most common patterns.1,2

Studies of CT findings in COVID-19 have reported pneumatoceles, or at least cystic changes, as a less common but potential complication of COVID-19 pneumonia with an incidence of 10%, as reported in the study by Shi et al.1–3 With a further case study reporting giant bulla formation in a patient who suffered COVID-19.4

Between April and May 2020, we identified three patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, who developed unusual radiological findings of large pneumatoceles during recovery from COVID-19. We share the in-hospital journey of three patients with interesting radiological findings and their clinical and radiological evolution during the first 12 months of recovery.

Case one

A 67-year-old male with a past medical history of diabetes mellitus type II and ulcerative colitis. He presented with worsening breathlessness and a dry cough. He was febrile, with C-reactive protein (CRP) elevated at 240 mg/L, and was diagnosed with COVID-19 pneumonia, following a positive COVID swab result. Initial chest X-ray showed diffuse infiltrations in the right middle zone (Figure 1). He made a rapid recovery on conservative treatment with empirical antibiotics (intravenous Amoxicillin and oral Clarithromycin) and anti-viral medication as part of a clinical trial (Lopinavir/Ritonavir 200/50). Throughout this admission, he did not require any form of invasive/non-invasive ventilation and was discharged in 6 days. Nine days later he was readmitted with breathlessness, haemoptysis, and pleuritic chest pain. Chest X-ray was consistent with COVID-19 pneumonia and computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) showed right lower lobe pulmonary embolism and bilateral ground-glass opacities. CT scan also revealed a possible left-sided loculated pneumothorax or bulla and a small right-sided cyst (Figure 2). He was treated conservatively with oxygen and low molecular weight heparin.

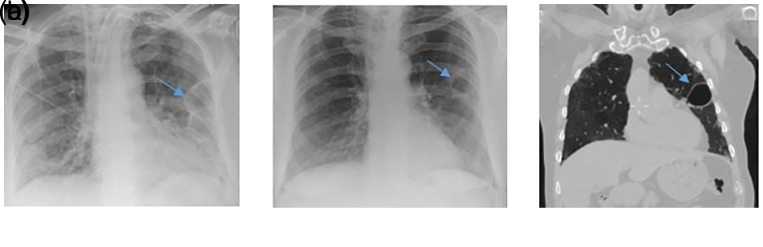

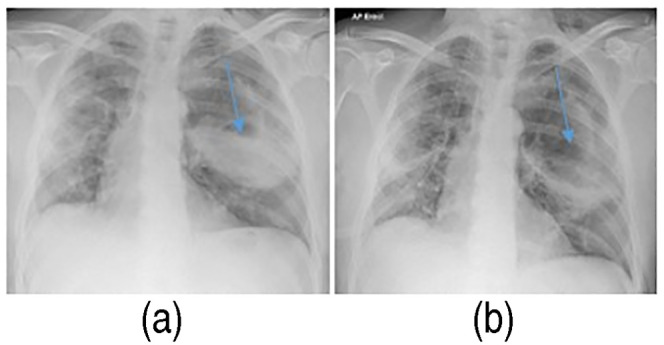

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray on admission with bilateral diffuse infiltrations centred in the right middle zone. The image quality is affected due to under penetration and slight rotation of the radiograph.

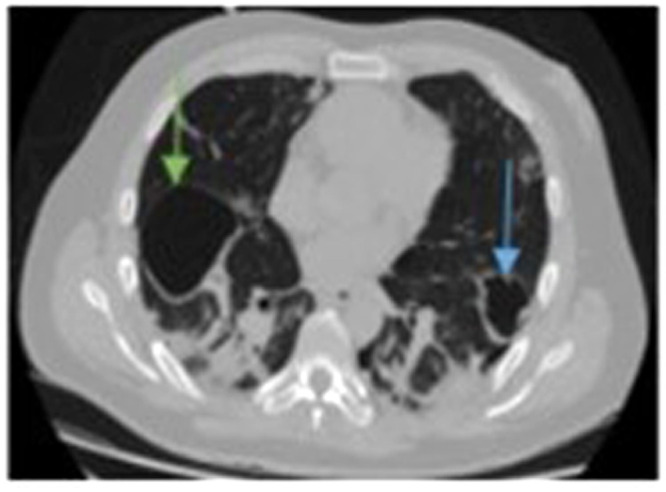

Figure 2.

Initial computed tomographic (CT) scan with a finding of air cavity, suggestive of left-sided, moderate in size loculated pneumothorax or potential bulla formation (blue arrow). A small cyst in the right upper lobe was also noted (green arrow).

Follow-up chest X-ray, 72 h after CTPA, showed air-fluid level in air locule which was confirmed with CT chest (Figure 3). The finding was suspicious for empyema. Therefore, he was commenced on empirical antibiotics, as there were no positive culture samples, and a decision was made for chest drain insertion. This was attempted under CT guidance but was unsuccessful, therefore no drain was placed. Post-procedural chest X-ray showed new iatrogenic peripheral pneumothorax with an obvious large pneumatocele partially filled with fluid. CT scan confirmed initially presumed left loculated pneumothorax was a fluid-filled pneumatocele, with a smaller right-sided pneumatocele with fluid (Figure 4). Conservative management was continued with antibiotics and oxygen therapy. Further chest X-ray showed pneumatocele still present (Figure 5(a)), but later fluid disappeared following episode of productive cough (Figure 5(b)). Appearances of pneumatocele were evident at discharge but the patient remained clinically stable.

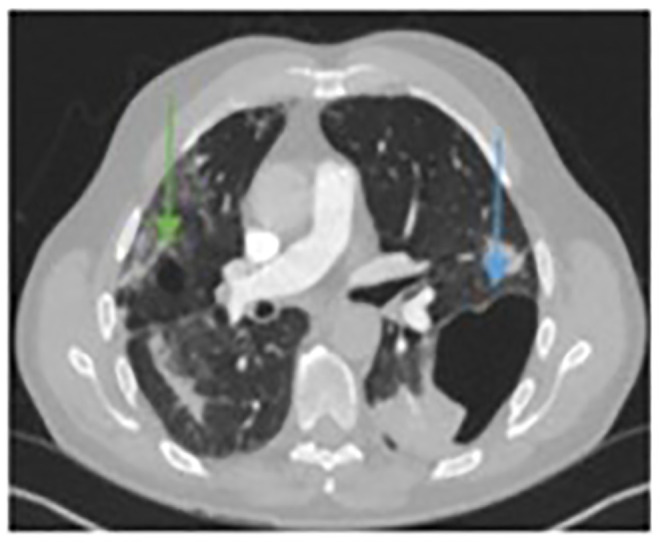

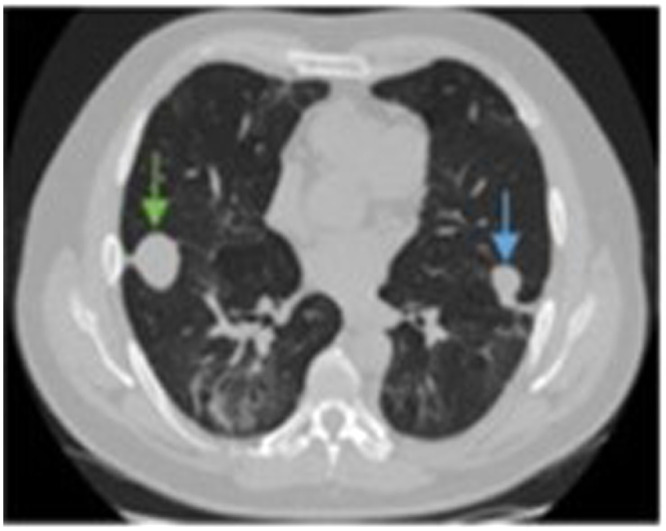

Figure 3.

The left-sided air cavity, gradually increasing in size and filling with fluid (blue arrow). The right-sided cyst has also enlarged (green arrow).

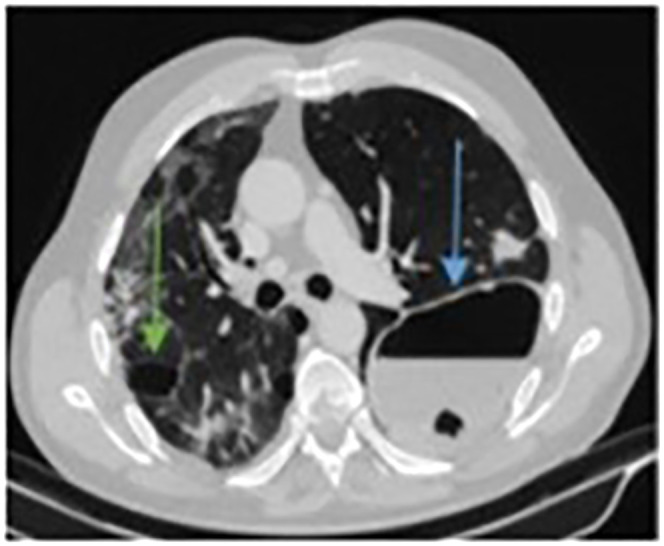

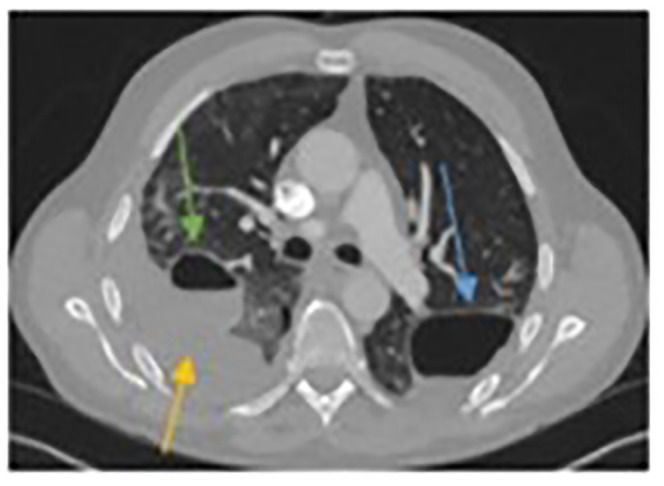

Figure 4.

Computed tomographic (CT) scan following attempts at CT-guided drain insertion, showing the persistence of the left-sided air cavity (blue arrow) with an obvious iatrogenic pneumothorax (yellow arrow). The right-sided air cavity continues to grow in size (green arrow).

Figure 5.

Chest X-ray showing the large left-sided pneumatocele, partially filled with fluid (blue arrow) (a). Follow-up chest X-ray showing the same left-sided pneumatocele being empty from fluid (blue arrow), following an episode of productive cough (b).

He was re-admitted with worsening right-sided pleuritic chest pain, cough with haemoptysis and increasing breathlessness. Blood tests revealed a raised CRP at 177 mg/L. Once more his chest X-ray showed no significant change but CTPA found a mildly enlarging right pneumatocele and no new PE (Figure 6). He was treated conservatively with empirical IV Amoxicillin with Clavulanic acid for infected pneumatocele. He remained stable throughout this admission and was discharged home with 2 weeks of oral antibiotics.

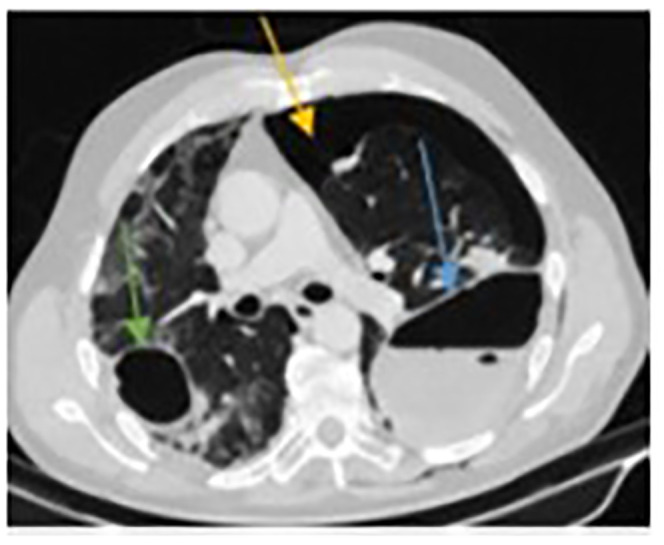

Figure 6.

Computed tomographic (CT) scan on re-admission with right chest pain. The left-sided pneumatocele is still obvious but decreased in size (blue arrow). The right-sided pneumatocele has started to fill with fluid (green arrow) and there is an obvious pleural effusion (yellow arrow).

A five-month follow-up X-ray confirmed the resolution of pulmonary changes with a reduction in the size of both pneumatoceles (Figure 7). At a 12-month follow-up, the patient had an almost complete recovery.

Figure 7.

Five-month follow-up chest X-ray after initial presentation. Small residual pneumatoceles in both lungs without any fluid in their cavities (blue arrows outline visible left lung findings).

Case two

A 71-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented with a ten-day history of dry cough, fever and progressing breathlessness. He was diagnosed with COVID-19 pneumonia and an initial chest X-ray demonstrated diffuse infiltrations (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Chest X-ray on admission with bilateral diffuse infiltrations.

Initially, he was treated with non-invasive ventilation in the form of continuous positive airway pressure. Four days later he deteriorated, requiring intubation and invasive ventilation. He was treated with steroids and antibiotics to cover super-imposed bacterial infection. He developed severe renal failure and soon required renal replacement therapy.

He tested negative for COVID-19 on three occasions and during recovery, almost 4 weeks after his admission, finding suspicious for cavitation was observed on his chest X-ray (Figure 9(a)). All subsequent follow-up chest X-rays, during his admission, had appearances of pneumatocele which remained uncomplicated and stable until his discharge. A three-month follow-up chest X-ray (Figure 9(b)) and CT scan (Figure 9(c)) confirmed the diagnosis, with moderate-sized pneumatoceles demonstrated in the left lung of each scan. Further CT scan, 9 months later, showed one of the pneumatoceles had completely resolved and the second was completely unchanged.

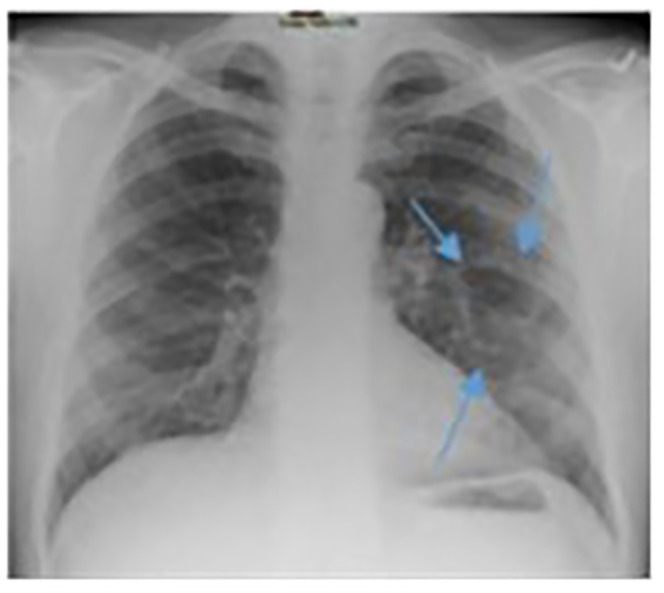

Figure 9.

Chest X-ray (CXR) in the recovery phase showed the left-sided pneumatocele (a), which persisted in a 3-month follow-up chest X-ray (b) and computed tomographic (CT) scan (c) (represented with a blue arrow in all images). Only one pneumatocele was demonstrated in these images.

Case three

A 47-year-old previously fit and non-smoking male presented with a 17-day history of fever, cough, and shortness of breath and was diagnosed with COVID-19. Rapidly, he developed severe hypoxia and was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit for invasive ventilation. His chest X-ray initially showed patchy consolidation throughout the right lung and left lung base (Figure 10). Following 4 days of invasive ventilation in combination with empirical antibiotic treatment (Amoxicillin with Clavulanic acid and Clarithromycin), he gradually improved and was finally discharged after 2 weeks. Ten days later he was readmitted with chest pain and progressing breathlessness. Chest X-ray revealed left-sided tension pneumothorax with mediastinal deviation to the right and cavitating lesion in the right lung (Figure 11(a)). Pneumothorax was drained immediately to treat tension pneumothorax (Figure 11(b)). Twenty-four hours later there was further clinical deterioration with progressing breathlessness. CTPA showed pulmonary embolism and bilateral pneumatoceles of various sizes (Figure 12). He was treated in a high dependency unit conservatively with oxygen, antibiotics and low molecular weight heparin. His recovery was no more complicated and he was finally discharged. Three-months follow-up CT chest showed significantly smaller pneumatoceles which were filled with fluid (Figure 13).

Figure 10.

Chest X-ray on admission with patchy consolidation throughout the right lung and less in the left lung base.

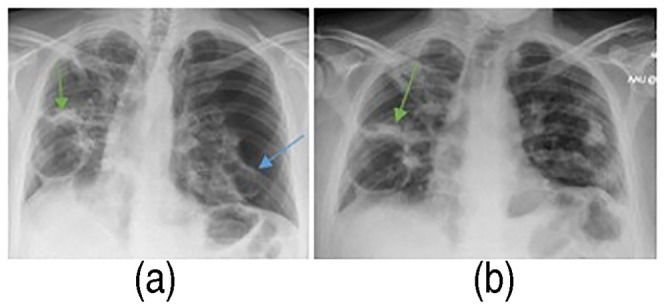

Figure 11.

Chest X-ray scan on re-admission showed the left-sided pneumothorax with mediastinal shift to right (blue arrow) and right-sided pneumatoceles (green arrow) (a). Resolved pneumothorax left, but right pneumatocele persists (green arrow) (b).

Figure 12.

Computed tomographic (CT) scan confirming the existence of right (green arrow) and left (blue arrow) pneumatocele formation at the same time with pulmonary embolism (not obvious in this image).

Figure 13.

Three-month follow-up CT scan. Decrease in right (green arrow) and left (blue arrow) pneumatoceles, which have been completely replaced by fluid.

Discussion

All three patients followed the same pattern; during recovery from COVID-19 (4–6 weeks after the first symptoms and 2–4 weeks after initial hospital admission), clinical deterioration triggered a further radiological investigation. At that point, the pneumatoceles were identified in areas of lung parenchyma where previously infective changes were observed.

Although there is literature suggesting that pneumatocele formation may be caused by invasive ventilation,5–7 this is not the common trend seen in our small cohort of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, as one of them did not even require invasive ventilation, one required it just for 4 days and the last for a long period of time. And if COVID-19 pneumonia can cause pneumatocele formation as part of its long-term sequelae, it is important clinicians recognize and manage this complication appropriately.

Pneumatoceles are a known complication of acute Staphylococcus pneumonia, especially in young children less than 4 years of age, and there is a decreasing incidence with age.8 However, other infectious and non-infectious aetiologies, or even a combination of them, have been reported to contribute in the formation of pneumatoceles. These include trauma, surgery, burns, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and mechanical ventilation, hydrocarbon inhalation and diffuse interstitial pulmonary emphysema.5–10

From what is reported in the literature, most pneumatoceles are asymptomatic and will resolve with conservative treatment.5,7 There is not an established algorithm in managing such a lung pathology. Invasive treatment usually takes the form of image-guided percutaneous chest drain insertion and should be reserved for patients who show signs of cardiorespiratory distress, such as tension pneumatocele, pneumothorax, haemothorax, and infected fluid-filled pneumatocele causing sepsis.5,7–9,11 In our first patient, we decided to intervene initially with an image-guided drain, in order to control his ongoing sepsis. The failure of the drain insertion and the fact that we were hesitant to drain it surgically at that point had, as a result, the resolution of the problem with the conservative only treatment, proving that the role of surgery is limited in these cases. Considering the level of success of conservative treatment, the risk of bleeding due to anticoagulation for the concomitant pulmonary embolism and the risk of exposure to high viral load for all the members of the operating team, the decision to intervene should be made only when all other measures fail or in life-saving cases. The indications for surgical intervention in patients with pneumatocele due to COVID-19 infection are the same as for any type of complicated pneumatocele:

Persistent air leak, haemothorax or pneumothorax following rupture.

Failure of lung expansion, in spite of drain insertion.

Progressive enlargement of the pneumatocele, causing compression of normal lung parenchyma and/or cardiorespiratory compromise.

Massive haemoptysis.

Abscess formation with ongoing sepsis.

Lack of response to conservative treatment.

In these cases, there are few possible options of surgical treatment, starting from deroofing or removal of the pneumatocele and extending to lung resections (lobectomy or rarely pneumonectomy) by thoracoscopic approach or thoracotomy.5,7,12–15 Currently, in the literature there is only one case report of a COVID-19 related pneumatocele that was treated surgically with deroofing due to respiratory compromise of the patient.14

Based on our own experience and what is reported in the literature, for COVID-19 related pneumatoceles, we advise plain chest X-rays to be utilized for diagnosis and monitoring, while CT scanning can be reserved to investigate causes of acute clinical or radiological deterioration. A conservative approach is recommended, focusing mainly on the management of the background COVID-19 infection.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Not Applicable.

Informed consent: All three patients have provided written consent about sharing their radiological images.

ORCID iD: Cameron McCann https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9184-1635

References

- 1.Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20: 425–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu J, Pan J, Teng Det al. et al. Interpretation of CT signs of 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Eur Radiol 2020; 30: 5455–5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J, Feng LC, Xian XY, et al. Novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) CT distribution and sign features. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2020; 43: 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun R, Liu H, Wang X. Mediastinal emphysema, giant bulla, and pneumothorax developed during the course of COVID-19 pneumonia. Korean J Radiol 2020; 21: 541–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serebrisky D, Atlas AB, Boyer D. Pneumatocele. Medscape. Accessed 18/04/2021. <https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1003289-overview>. 2016.

- 6.Al-Ghafri M, Al-Hanshi S, Al-Ismaily S. Two cases of pneumatoceles in mechanically ventilated infants. Oman Med J 2015 Jul; 30: 299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamil A, Kasi A. Pneumatocele [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan.

- 8.Gholap PM, Shankar SA. A rare case of tension pneumatocele. Indian J Tuberc 2017; 64: 327–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryou SH, Bae JW, Baek HJ, et al. Pulmonary pneumatocele in a pneumonia patient infected with extended-Spectrum β-lactamase producing Proteus mirabilis. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2015; 78: 371–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph L, Shahroor S, Fisher Det al. et al. Conservative treatment of a large post-infectious pneumatocele. Pediatr Int. 2010; 52: 841–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazer S, Söylemez UPO. Clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of traumatic pulmonary pseudocysts. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2018; 24: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shishido Y, Minami K, Sakanoue Iet al. et al. Large traumatic pneumatocele treated using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2019; 86: 1039–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerdung CA, Ross BC, Dicken BJet al. et al. Pneumonectomy in a child with multilobar pneumatocele secondary to necrotizing pneumonia: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Pediatr 2019; 2019: 2464390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamad A-MM, El-Saka HA. Post COVID-19 large pneumatocele: clinical and pathological perspectives. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2021; 33: 322–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiBardino DJ, Espada R, Seu Pet al. et al. Management of complicated pneumatocele. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003; 126: 859–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]