Abstract

This study uses SSR Health data on drug list prices and estimated net prices after manufacturer discounts to evaluate trends in prices for newly marketed brand-name prescription drugs in the US from 2008 to 2021.

Prescription drug spending in the US exceeded half a trillion dollars in 2020.1 Spending is driven by high-cost brand-name drugs, for which manufacturers freely set prices after approval.2 Rising brand-name drug prices often translate to payers restricting access, raising premiums, or imposing unaffordable out-of-pocket costs for patients. We evaluated recent trends in prices for newly marketed brand-name drugs.

Methods

We identified drugs newly marketed from 2008 to 2021 within SSR Health, a database with quarterly wholesale acquisition cost (ie, list prices) and estimated net prices after manufacturer discounts for more than 1230 brand-name products.3 For drugs with multiple dosage forms, we included the first marketed version. Price per unit was converted to price per year (or course of treatment, if <1 year) based on US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved labeling; in cases of weight-based dosing, US population averages were used. Prices were converted to 2021 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers.

We used linear regression to estimate trends in mean launch prices, which were log transformed to improve normality and fit observed exponential trends. We adjusted for drug characteristics, including biologics vs small molecules, novel active ingredients vs reformulations, accelerated vs traditional FDA approval, Orphan Drug Act designation for rare conditions vs nonrare conditions, oncology vs nononcology indications, and oral vs injected vs other route of administration. In a secondary analysis, we included interaction terms between each characteristic and time to determine if trends varied between subgroups (2-tailed; P < .05). In another secondary analysis, we used estimated net prices after manufacturer discounts among non-Medicaid payers, if such estimates were available from SSR Health within 1 year after launch. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

We included 548 of 576 drugs (95%) first marketed in 2008-2021, excluding 3 diagnostics and 25 drugs for which we could not estimate price per year (eg, as-needed use). Overall, 357 (65%) were new molecules, 139 (25%) were biologics, 182 (33%) treated rare diseases, 64 (12%) received accelerated approval, 119 (22%) were oncologic agents, and 282 (51%) were orally administered (Table). The highest prices were among drugs for rare diseases (median, $168 441 [IQR, $78 291-$338 379] per year) and oncology drugs (median, $155 091 [IQR, $109 832-$233 916] per year).

Table. Differences in Prices and Price Trends for Newly Marketed Drugs From 2008-2021, by Drug Characteristics.

| Drug characteristicsa | Drugs, No. (%) | Price per y, 2008-2021, median (IQR), $ | Adjusted relative differences in mean priceb | Adjusted absolute difference in % price increase per yc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | P value | Estimate (95% CI) | P value | |||

| All drugs | 548 | 20 657 (3929-138 509) | ||||

| Novelty | ||||||

| New active ingredient | 357 (65) | 68 596 (7276-184 065) | 1.7 (1.2-2.2) | .001 | 0.4 (–6.9 to 8.3) | .91 |

| Reformulationd | 191 (35) | 5429 (2105-18 782) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Ingredient type | ||||||

| Biologic | 139 (25) | 84 508 (18 861-288 759) | 2.2 (1.5-3.4) | <.001 | 13.7 (2.9 to 25.7) | .01 |

| Small molecule | 409 (75) | 10 580 (3076-98 516) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Approval pathway | ||||||

| Accelerated approvale | 64 (12) | 168 344 (115 609-240 302) | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) | .75 | –0.4 (–11.2 to 11.6) | .94 |

| Traditional approval | 484 (88) | 12 912 (3434-96 030) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Patient population | ||||||

| Raref | 182 (33) | 168 441 (78 291-338 379) | 6.8 (5.0-9.2) | <.001 | 8.1 (0.5 to 16.4) | .04 |

| Nonrare | 366 (67) | 6252 (2675-33 227) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Indication | ||||||

| Oncology | 119 (22) | 155 091 (109 832-233 916) | 3.7 (2.5-5.3) | <.001 | –10.3 (–18.3 to –1.5) | .02 |

| Nononcology | 429 (78) | 7783 (2963-52 483) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Route of administration | ||||||

| Oral | 282 (51) | 15 630 (3948-115 609) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Injected | 199 (36) | 72 875 (9908-236 164) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | .70 | –6.0 (–14.3 to 3.0) | .19 |

| Otherg | 67 (12) | 3545 (1542-6689) | 0.4 (0.3-0.6) | <.001 | –0.5 (–10.4 to 10.4) | .92 |

Drug characteristics were obtained from Drugs@FDA, linked to SSR Health data based on brand name.

Estimates are from a linear regression model of log-transformed price; the model included year of market entry (rounded to calendar quarter) plus all listed characteristics as independent variables. The results shown are exponentiated coefficients and reflect the relative difference in mean price, adjusting for all other characteristics and time. For example, mean prices for oncology drugs were 3.7 times higher than those for nononcology drugs.

Estimates are from a second linear regression model that additionally included interaction terms between year of market entry and each characteristic. The results shown are based on exponentiated coefficients and reflect the difference in the annual percent increase in price. For example, mean prices for oncology drugs increased by 10.3% per year less than those for nononcology drugs.

Reformulations included any product for which the US Food and Drug Administration had previously approved a different product with the same active ingredient. This included new formulations of existing drugs (eg, long-acting depot injections), new manufacturers, and new combination products.

The US Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval program allows approval of drugs that treat a serious condition or fill an unmet need to be approved based on evidence of efficacy using a surrogate end point that is only reasonably likely to predict a clinical end point.

Under the Orphan Drug Act, a drug is intended to treat a rare condition that affects fewer than 200 000 individuals in the US.

Includes 18 inhaled, 18 transdermal, 9 ophthalmic, 7 nasal, 5 vaginal, 4 implanted, 4 sublingual, 1 instilled, and 1 rectal.

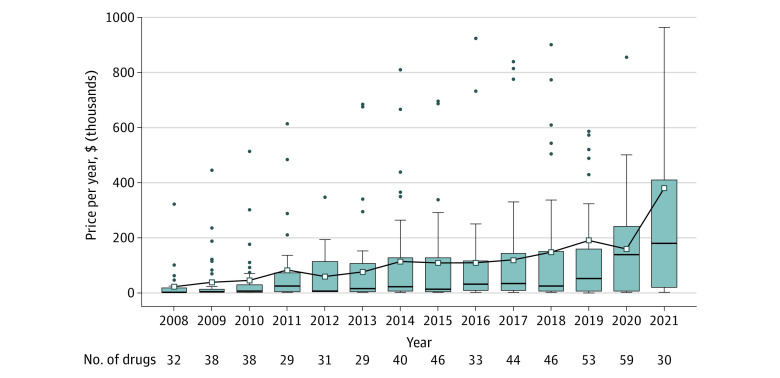

Median launch prices increased from $2115 per year (IQR, $928-$17 866) per year in 2008 to $180 007 (IQR, $20 236-409 732) per year in 2021 (Figure). The proportion of drugs priced at $150 000 per year or more was 9% (18/197) in 2008-2013 and 47% (42/89) in 2020-2021. Unadjusted mean launch prices increased exponentially by 20.4% per year (95% CI, 15.3%-25.8% per year). Adjusting for drug characteristics, mean prices increased exponentially by 13.0% per year (95% CI, 9.4%-16.7% per year). Most drug characteristics were independently associated with launch price, and including interaction terms revealed that launch prices increased more quickly among biologics, drugs treating rare diseases, and nononcology drugs (Table).

Figure. Prices for Newly Marketed Drugs, 2008-2021.

Each box-and-whisker plot represents the price per year (in 2021 US dollars) of drugs first marketed each year, from 2008 to 2021. Boxes indicate 25th to 75th percentiles; horizontal lines, medians; white squares, means. Outliers are shown except for 6 drugs with launch prices exceeding $1 million per year: sebelipase alfa (Kanuma, 2015; $1.2 million per year), inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa, 2018; $1.0 million per year), tagraxofusp-erzs (Elzonris, 2019; $2.2 million per year), onasemnogene abeparvovec (Zolgensma, 2019; $2.2 million per year), naxitamab-gqgk (Danyelza, 2021; $3.2 million per year), and asparaginase erwinia chrysanthemi-rywn (Rylaze, 2021; $1.6 million per year). Date of market entry was determined primarily based on the first year a price was listed in SSR Health. However, if the first listed price in SSR Health occurred 1 year or more after US Food and Drug Administration approval, an industry database (IBM Red Book) was used to verify and correct, if necessary, the date of market entry and launch price.

Estimated net prices were available for 395 drugs (72%); these net prices were a median of 14% lower than the wholesale acquisition cost in 2008 and 24% lower in 2020. Net prices increased from a median of $1376 (IQR, $693-$10 897) in 2008 to $159 042 (IQR, $31 187-$380 509) in 2021. Adjusting for drug characteristics, mean net prices increased exponentially by 10.7% per year (95% CI, 6.3%-15.2% per year).

Discussion

From 2008 to 2021, launch prices for new drugs increased exponentially by 20% per year. In 2020-2021, 47% of new drugs were initially priced above $150 000 per year. Prices increased by 11% per year even after adjusting for estimated manufacturer discounts and changes in certain drug characteristics, such as more oncology and specialty drugs (eg, injectables, biologics) introduced in recent years. The study was limited to drugs sold by public companies; SSR Health net price estimates have limitations, including underestimating net prices paid by payers.3,4

The trend in prices for new drugs outpaces growth in prices for other health care services.5 Even after drugs are marketed, manufacturers routinely increase prices over time; in another analysis, net prices increased by 4.5% per year from 2007 to 2018.3 In response to the current trends, the US could stop allowing drug manufacturers to freely set prices and follow the example of other industrialized countries that negotiate drug prices at launch.6

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

References

- 1.IQVIA Institute . The Use of Medicines in the US: Spending and Usage Trends and Outlook to 2025. Published May 27, 2021. Accessed January 4, 2022. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/the-use-of-medicines-in-the-us?utm_campaign=2021_USMedsreportpromo_Enterprise_TC&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Eloqua

- 2.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: origins and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2016;316(8):858-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez I, San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Gellad WF. Changes in list prices, net prices, and discounts for branded drugs in the US, 2007-2018. JAMA. 2020;323(9):854-862. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman WB, Rome BN, Raimond VC, Gagne JJ, Kesselheim AS. Estimating rebates and other discounts received by Medicare Part D. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(6):e210626. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartman M, Martin AB, Washington B, Catlin A; National Health Expenditure Accounts Team . National health care spending in 2020: growth driven by federal spending in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(1):13-25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rand LZ, Kesselheim AS. An international review of health technology assessment approaches to prescription drugs and their ethical principles. J Law Med Ethics. 2020;48(3):583-594. doi: 10.1177/1073110520958885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]