Abstract

Tissue plasminogen activator’s (tPA) fibrinolytic function in the vasculature is well-established. This specific role for tPA in the vasculature, however, contrasts with its pleiotropic activities in the central nervous system. Numerous physiological and pathological functions have been attributed to tPA in the central nervous system, including neurite outgrowth and regeneration; synaptic and spine plasticity; neurovascular coupling; neurodegeneration; microglial activation; and blood-brain barrier permeability. In addition, multiple substrates, both plasminogen-dependent and -independent, have been proposed to be responsible for tPA’s action(s) in the central nervous system. This review aims to dissect a subset of these different functions and the different molecular mechanisms attributed to tPA in the context of learning and memory. We start from the original research that identified tPA as an immediate-early gene with a putative role in synaptic plasticity to what is currently known about tPA’s role in a learning and memory disorder, Alzheimer’s disease. We specifically focus on studies demonstrating tPA’s involvement in the clearance of amyloid-β and neurovascular coupling. In addition, given that tPA has been shown to regulate blood-brain barrier permeability, which is perturbed in Alzheimer’s disease, this review also discusses tPA-mediated vascular dysfunction and possible alternative mechanisms of action for tPA in Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

Keywords: Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), Alzheimer’s disease, learning and memory, vascular dysfunction, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)

Introduction

The serine protease tissue-plasminogen activator (tPA), classically known for its role in fibrinolysis, is also expressed on the abluminal side of the vasculature in the central nervous system. Seminal in vivo studies demonstrated that brain tPA is upregulated following activity-dependent events in the hippocampus and cerebellum, suggesting a physiological role for tPA in synaptic plasticity and learning and memory1, 2. These reports, however, were followed by others that showed a pernicious role for tPA in neurodegeneration, microglial activation, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability3–5. Moreover, a variety of plasminogen-dependent and plasminogen-independent substrates and receptors have been reported to effectuate tPA’s actions in these processes, including N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR), platelet-derived growth factor-CC (PDGF-CC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-related protein (LRP1), and pro-brain derived neurotrophic factor (pro-BDNF)5–8. To contextualize these varied reports, this review uses learning and memory as a paradigm to examine and analyze tPA’s actions in the central nervous system. It summarizes the foundational studies implicating tPA in synaptic plasticity and synaptic transmission, and it re-examines those studies considering more recent reports demonstrating a role for tPA in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis.

AD is a degenerative brain disease characterized by amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques, tau neurofibrillary tangles, and progressive cognitive decline9. Though Aβ and tau are hallmark pathologies of AD, accumulating evidence indicates that vascular dysfunction also plays a significant contributory, if not causal, role in disease progression10. Indeed, more contemporary studies in AD patients and in AD mouse models demonstrate that targeting vascular pathologies slows the clinical and pathological manifestations of AD11, 12. Accordingly, this review discusses the putative roles for tPA in AD, including Aβ clearance and neurovascular coupling, and how tPA provides a possible mechanistic link between Aβ and vascular pathology. In addition, it proposes alternative pathways through which tPA could act on the vasculature to promote AD pathology.

Role of tPA in synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity

Upregulation of tPA following activity-dependent events

A role for tPA in learning and memory was first suggested when tPA was shown to be an immediate-early gene that was induced by neuronal activity1. In that study, tPA was identified in a differential screen of 30,000 clones from a complementary DNA library; using three activity-dependent events – seizure, long-term potentiation (LTP), and kindling – tPA gene expression was upregulated in vivo within 1 hour in the granule and pyramidal cell layers of the hippocampus in the adult rat brain. Consistent with these data, tPA was found to be induced in the cerebellum of rats after learning a complex motor task2. Using a pegged runway of regular and irregular patterning to test cerebellar-dependent motor learning, tPA mRNA expression was upregulated in Purkinje cells during the most active phase of learning. These spatial and temporal data suggested that tPA may have a role in learning and memory by regulating neuronal plasticity.

Modulation of basal synaptic transmission by tPA

Further studies deconstructing tPA’s role in hippocampal plasticity ex vivo, however, have yielded somewhat varied results. While some groups have observed defects in basal synaptic transmission13 and early14 and late LTP (L-LTP) in the hippocampal CA1 region of tPA−/− mice, others have not15, 16. Frey and colleagues13 were the first to report deficits in synaptic efficacy at the Schaffer collateral-to-CA1 synapse in tPA−/− mice under basal conditions. In tPA−/− mice, a larger stimulus was needed to evoke synchronous somatic action potentials (so called “pop-spike”) of similar amplitude to that seen in wild-type mice. In addition, paired-pulse facilitation of the pop-spike was significantly reduced in the tPA−/− mice, while paired-pulse facilitation of the field excitatory post-synaptic potential was largely unaltered. These results suggest that CA3-CA1 synapses in tPA−/− mice are under enhanced γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic inhibition, especially since increased facilitation was observed when slices were treated with the GABAA receptor competitive antagonist bicuculline. Consistent with the hypothesis that tPA−/− mice have altered GABAergic transmission, no differences in L-LTP between tPA−/− mice and wild-type mice were found, but significant differences were observed when GABAergic transmission was blocked with the noncompetitive GABAA channel blocker picrotoxin13.

More recently, it was proposed that tPA modulates pre-synaptic transmission through its effects on synaptic vesicle cycling17. From immunoblots of neuronal membrane extracts and isolated synaptic fractions from synaptoneurosomes, tPA treatment was found to recruit βII-spectrin, a cytoskeletal protein implicated in synaptic vesicle release, to the active zone and induce the binding of synaptic vesicles to βII-spectrin. Treatment with tPA also induced phosphorylation of synapsin I, a synaptic vesicle membrane protein, presumably via tPA-mediated increases in voltage-gated calcium channel expression. In keeping with these expression and localization studies, tPA treatment was shown to increase the frequency of miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents in CA1 pyramidal neurons from rat brain slices17. Mechanistic studies investigating whether tPA increases the release probability of individual synaptic vesicles or the number of synaptic vesicles released were not performed. Moreover, it is unclear if this increase in miniature excitatory post-synaptic current frequency is due to tPA-mediated increases in the expression/recruitment of presynaptic vesicle cycling proteins to the active zone. Further studies, therefore, are necessary to determine if these reported effects of tPA are linked and if they are responsible for the defects in basal synaptic transmission first observed in tPA−/− mice13.

Alternatively, in experiments utilizing neuronal cortical cultures, tPA treatment was shown to increase p-35 cyclin-dependent kinase-5/Ca2+ calmodulin-dependent kinase IIα (Cdk5/CaMKIIα) activation, and attenuate NMDA-induced decreases in post-synaptic density-95 and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) levels18, 19. Changes to post-synaptic AMPAR have long been known to contribute to synaptic efficacy and synaptic plasticity20. Though, roscovitine, a broad-range purine inhibitor of multiple cyclin-dependent kinases, including Cdk5, appeared to abrogate the effects of tPA treatment18, more mechanistic studies are needed to demonstrate if the observed effects of tPA are within the same pathway and if they cause changes in synaptic transmission. Moreover, decreased, not increased, Cdk5 activity has been reported to be responsible for NMDAR-induced AMPAR endocytosis21, further highlighting the importance of future experiments that directly test tPA-mediated Cdk5 signaling and its potential downstream effects on synaptic transmission.

Loss of tPA results in impairments in long-term potentiation

Despite these studies, however, other groups have reported no differences in basal synaptic transmission in tPA−/− mice14–16. Specifically, these reports show no differences in basal synaptic transmission in the CA1 hippocampal region of tPA−/− compared to wild-type mice, but significant defects in L-LTP, with or without blocking GABAergic transmission14–16. It has also been shown that maintenance of L-LTP at the Schaffer collateral-to-CA1 synapse can be diminished by application of the protease inhibitor tPA-Stop22. Conversely, potentiation can be enhanced when tetanization is coupled with either pharmacologic16 or genetic23 increases in tPA. It was further demonstrated that this potentiation in CA1 requires activation of the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated pathway15, 22, as analogs of cAMP and activators of cAMP/PKA-dependent signaling cascades can induce L-LTP in wild-type, but not tPA−/− mice. Consistent with this, the tPA gene, Plat, has previously been shown to house a cAMP responsive element promoter24.

The endocytic signaling receptor, LRP1, on neurons has also been implicated in mediating tPA’s actions in L-LTP16. Blocking LRP1 with an inhibitor, receptor-associated protein (RAP), caused deficits in L-LTP that were similar to what was reported previously for tPA−/− mice. Moreover, RAP blocked Schaffer collateral-to-CA1 synaptic potentiation in tPA−/− hippocampal slices that had been treated with tPA. PKA, a kinase known to play a key role in the induction and maintenance of L-LTP25, was also shown to be activated upon tPA binding to LRP1. Together, these data support a LRP1-mediated mechanism of action for tPA in L-LTP. In addition, they suggest that tPA’s protease activity is not necessary for the full expression of L-LTP, as proteolytically active tPA is not required to interact with and signal through LRP126.

While the involvement of LRP1 in tPA-mediated L-LTP implicates tPA as having a plasminogen-independent mechanism of action, tPA/plasmin-induced cleavage of BDNF has also been demonstrated to be essential for long-term hippocampal plasticity8. Previously, genetic or pharmacologic ablation of BDNF or its receptor TrkB was shown to inhibit L-LTP27–30. It was also previously demonstrated that secreted proBDNF can be cleaved extracellularly by plasmin into mature BDNF (mBDNF)31. It was not known, however, if the tPA/plasmin/mBDNF pathway formed a common pathway important for hippocampal L-LTP.

Through a series of L-LTP experiments using tPA−/− mice, plasminogen deficient mice, and mice heterozygous for BDNF, it was demonstrated that tPA/plasmin-mediated cleavage of proBDNF is critical for the full expression of L-LTP in the CA1 region of the mouse hippocampus8. Subcellular localization studies support these functional findings. In cultured hippocampal neurons transfected with BDNF-mCherry and tPA-EYFP vectors, BDNF and tPA were shown to be co-packaged in presynaptic dense core vesicles32, suggesting that tPA and BDNF are proximally localized and likely concomitantly released to act through a common pathway.

Interestingly, while these experiments were focused upon long-term plasticity in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, both BDNF and tPA have been shown to be most highly expressed in giant mossy fiber boutons in the mossy fiber pathway in the CA3 region of the hippocampus33–36. In addition to en passant terminals and filopodial extensions, giant mossy fiber boutons are one of three identified presynaptic specializations that emanate from the mossy fiber axons of dentate granule neurons37, 38. The subcellular localization of both BDNF and tPA within giant mossy fiber boutons, therefore, not only indicates that these two proteins are proximally localized to act in concert but suggests that their role in synaptic plasticity is highly compartmentalized and possibly unique to mossy fiber-to-CA3 synaptic plasticity. While deficits in L-LTP have been reported in tPA−/− mice at the mossy fiber-to-CA3 cell synapse15, 22, functional consequences of tPA/plasmin-mediated mBDNF generation have not been tested in the CA3 region specifically.

Behavioral consequences of tPA deficiency

Mice deficient in tPA display defects in avoidance behavior

Given the deficits in hippocampal L-LTP in tPA−/− mice, it was thought that they would exhibit comparable behavioral deficits in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory tasks. While there is conflicting data on whether loss of tPA causes overt cognitive defects14, 15, 39, tPA−/− mice have been consistently found to have impairments in avoidance tests14, 15, 39. Avoidance tests require the mouse to learn to avoid an adverse stimulus, usually foot shock. Depending on the experimental design, avoidance tests can reveal differences in acquisition, working memory, consolidation, and long-term recall40. In addition, methods by which the adverse stimulus is presented to the mouse - in an active or passive way - can alter the cognitive difficulty and effect the type of learning being tested and brain structures involved.

Mice lacking the tPA gene have been tested in both two-way shuttle box active avoidance15, 22 and step-down passive avoidance39. In a two-way shuttle box active avoidance test, mice are trained to avoid a foot shock upon the presentation of a light cue. It is inferred that mice have successfully learned the task if they associate the light cue with the oncoming foot shock and avoid the shock by moving to the neighboring compartment. Using this paradigm, tPA−/− mice were found to have significant defects in their ability to avoid the aversive stimulus. Similarly, in a step-down passive avoidance test, mice are placed on a raised platform and learn to not step-down onto the lower platform, which is formed by an electrical grid, thereby avoiding a foot shock. In the step-down passive avoidance test, tPA−/− mice had significantly shorter latencies to step-down than wild-type mice. Taken together, these studies suggest that tPA−/− mice have deficits in acquisition or working memory required for aversive associative learning. However, this interpretation is complicated by the role tPA has been shown to have in the amygdala function and anxiety-like behavior41 (see next section).

Key role for tPA in anxiety-like behavior

Mice deficient in tPA have been found to be resistant to stress-induced anxiety, with no changes in basal anxiety39, 42, 43. Basal anxiety was tested using elevated-plus maze, which takes advantage of a rodent’s natural aversion to open spaces and preference for closed spaces; tPA−/− mice were found to spend equivalent time in the open arms compared to wild-type mice. However, when tPA−/− and wild-type mice were first subjected to bouts of chronic restraint42 or injections of corticotropin-release factor43, tPA−/− mice did not exhibit the expected stress-induced anxiety-like behavior (significantly less time in open arms) when compared with wild-type mice. Moreover, the increased stress-induced anxiety-like behavior observed in wild-type mice correlated with increased tPA activity in the central and medial amygdala, but not the basolateral amygdala42. In line with this phenotype and in-keeping with tPA promoting anxiety-like behavior, intraventricular injections of the stress hormone, corticotropin-releasing factor, were found to upregulate tPA activity in the central and medial amygdala43.

The molecular mechanism for tPA’s role in facilitating anxiety-like behavior points to plasminogen-independent neuronal remodeling, with evidence demonstrating that: 1) plasminogen null mice do not phenocopy tPA−/− mice42, 2) signaling cascades implicated in spine plasticity44 are upregulated in wild-type, but not tPA−/− mice42, and 3) tPA−/− mice have significantly attenuated stress-induced spine retraction in the medial amygdala compared to wild-type mice45. Given the behavioral data, it is possible that the impairments observed in tPA−/− mice in avoidance tasks are due to tPA’s effect on stress-induced neuronal plasticity in the amygdala and not a direct effect of tPA on the neural substrates that underlie hippocampal-dependent learning and memory. Recognizing the importance of stress-susceptibility on behavioral performance46, future studies that employ task-independent stressors to test learning and memory 47 would be informative in discriminating between tPA’s role in stress versus learning and memory.

Role of tPA in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis

Mechanisms of tPA-mediated neuropathology and cognitive deficits

Despite the cumulative work demonstrating that tPA modulates synaptic transmission and plasticity, most studies of tPA in AD have not focused on synaptic pathology; though one group has shown that inhibition of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), an endogenous inhibitor of tPA, ameliorates hippocampal LTP deficits in the amyloidogenic Tg2576 AD mouse model48 (See Table 1 for a summary mouse models of AD-related neuropathology discussed in this review). In fact, most studies on tPA’s role in AD pathogenesis have concentrated on tPA-mediated clearance of Aβ plaques49–55. One of the hallmark neuropathologies associated with AD is the deposition of Aβ plaques in the brain parenchyma and cerebrovasculature; an imbalance in amyloid precursor protein (APP) production and Aβ clearance is thought to contribute to AD pathogenesis56.

Table 1.

Mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease-related neuropathology

| Mouse model | Genes | Mutations | Genetic background | Primary reference | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5×FAD | APP, PSEN1 | Human APP770 KM670/671NL (Swedish), APP I716V (Florida), APP V717I (London), PSEN1 M146L (A > C), PSEN1 L286V | C57BL/6 × SJL | 135 | 12, 132 |

| J20 FAD | APP | Human APP770 KM670/671NL (Swedish), APP V717F (Indiana) | C57BL/6 | 136 | 86 |

| APP/PS1 | APP, PSEN1 | Human APP770 KM670/671NL (Swedish), PSEN1:deltaE9 | C57BL/6 × C3H | 137 | 78, 85, 108 |

| APPs1 | APP | Human APP751 isoform KM595/596NL (Swedish), V642I (London) | C57BL/6 × CBS | 138 | 72 |

| Tg2576 | APP | Human APP770 KM670/671NL (Swedish) | B57BL/6 × SJL | 139 | 48, 53, 55, 77, 79 |

| Tg4510 | MAPT | Human MAPT P301L | 129S6 × FVB | 140 | 73 |

| PSAPP | APP, PSEN1 | Human APP770 KM670/671NL (Swedish), PSEN1 M146L (A > C) | B57BL/6 × D2 × Swe × SJL | 141 | 48 |

APP, amyloid precursor protein; FAD, familial Alzheimer’s disease; PS, presenilin 1; PS1, presenilin 1; PSEN1, presenilin 1; MAPT, microtubule-associated protein tau.

Through its proteolytic activity, the tPA/plasmin system has been shown to promote α-secretase cleavage of APP50, shuttling the APP production pipeline toward the non-amyloidogenic pathway, and degrade Aβ in vitro48–52. Moreover, Aβ appears to act like a fibrin(ogen)-mimic, catalyzing plasminogen activation by tPA, and stimulating tPA activity via feedforward mechanisms in vitro57–60.

Other studies have focused on tPA’s interaction with LRP1 to modulate Aβ uptake and influence AD pathogenesis. Immunohistochemistry of LRP1 and tPA, along with other LRP1 ligands like apolipoprotein E, α−2 macroglobulin, urokinase plasminogen activator, PAI-1, lipoprotein lipase, and lactoferrin, have been observed in Aβ plaques from human AD brain tissue61. Though no direct studies have investigated the effects of tPA on LRP1-mediated clearance of Aβ, other LRP1 ligands, like α−2 macroglobulin and lactoferrin, have been shown to enhance clearance of soluble Aβ in vitro62. Indeed, LRP1 is a well-established contributor to AD pathology. It is expressed on neurons, microglia, astrocytes, endothelial cells, choroid plexus epithelial cells, pericytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells, where it mediates Aβ uptake and trafficking to the lysosome for degradation or across the BBB for clearance63–70.

This apparent protective effect of tPA/plasmin activity on direct Aβ degradation or LRP1-mediated clearance, however, appears to be blunted in vivo by upregulated expression of PAI-1. PAI-1, which increases with age and diseases of the central nervous system in humans71, is also upregulated in amyloidogenic AD mouse models, including Tg257653, APPs172, and PSAPP48, and the tauopathy AD mouse model Tg451073. Concomitant with the increased expression of PAI-1 is a reduction in tPA activity, but not mRNA expression or total protein, in vivo72, suggesting a post-translational inhibitory mechanism of action. This seeming discrepancy between the in vitro and in vivo effects of the tPA/plasmin pathway may be due to the in vivo microenvironment (e.g., chronic inflammation), comorbidities (including age), and/or genetic and lifestyle factors that influence AD susceptibility74–76. Any one or more of these factors, therefore, may alter the ability of the tPA/plasmin system to exert regulatory control over Aβ aggregation and AD pathogenesis.

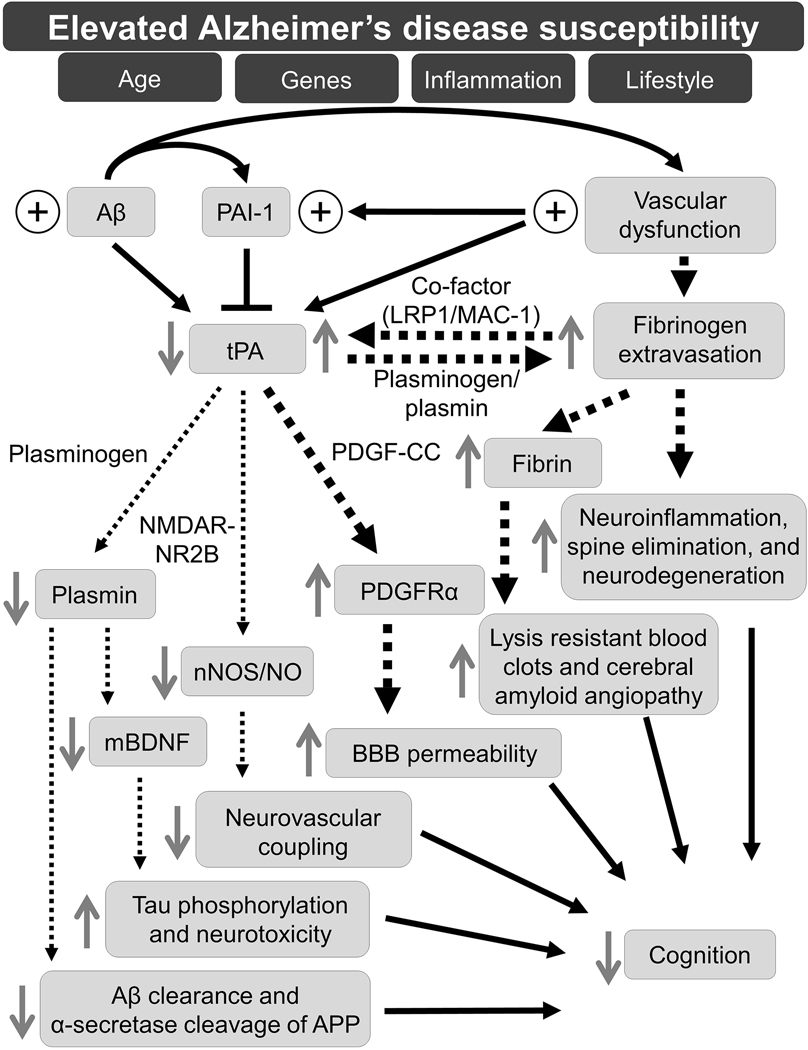

The working model presented in Figure 1 is supported by in vivo evidence from PAI-1−/− and tPA−/− mice that have been crossed with the amyloidogenic APP/PS1 and Tg2576 AD mice, respectively54, 55, and from pharmacologic studies that show activation of the tPA/plasmin system with PAI-1 inhibitor treatment48, 77, 78. In brain homogenates from APP/PS1/PAI-1−/− mice, both tPA and plasmin activity were shown to be elevated when compared with APP/PS1/PAI-1+/− mice (birth and survival rates for APP/PS1/PAI-1+/+ mice were too low for comparison), and this increased tPA/plasmin activity was associated with reduced Aβ burden54. Similarly, when Tg2576 mice were crossed with tPA−/− mice, Tg2576/tPA+/− mice were found to have greater Aβ burden than their Tg2576/tPA+/+ controls (birth and survival rates for Tg2576/tPA−/− mice were too low for comparison)55.

Figure 1. Working model of tPA-mediated pathways in AD pathogenesis.

This working model proposes that risk factors, including, age, genes, inflammation, and lifestyle, promote an environment of high susceptibility to AD development. One or more of these risk factors can initiate a cascade of pathological responses involving tPA that culminate in cognitive deficits. This cascade of tPA-mediated pathways, within a high AD susceptibility milieu, is initiated by the pathological interplay of elevated (plus sign) Aβ and vascular dysfunction, which contribute to increased levels (plus sign) of PAI-1. Thick black, dotted arrows represent physiological or pathological processes upregulated by increased levels of tPA activity, and thin black, dotted arrows represent physiological or pathological pathways downregulated by decreased levels of tPA activity. Gray, solid arrows represent the effect of tPA and/or plasmin on the corresponding protein or process. Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid-β; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; LRP1, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1; MAC1, macrophage-1 antigen; PDGF-CC, platelet-derived growth factor-CC; NMDAR; N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; NR2B, NMDAR subtype 2B; PDGFRα, platelet-derived growth factor receptor α; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; mBDNF, mature brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BBB, blood-brain barrier; APP, amyloid precursor protein.

Reports on Aβ clearance via activation of the tPA/plasmin system with pharmacologic inhibition of PAI-1 are variable in AD mouse models: some show reduced Aβ burden, while others show no change48, 77–79. It’s likely that differences in detection method (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] versus immunohistochemical staining), tissue sample (whole brain homogenates versus cortical and/or hippocampal sections), and form of angiopathy (insoluble versus soluble and cerebral amyloid angiopathy versus parenchymal Aβ) are responsible for the discrepancy. Moreover, it’s possible that off-target effects of PAI-1 inhibition, not increased tPA/plasmin activity, are responsible for the increased Aβ degradation and clearance in AD mice with inhibitor treatment. Interestingly, oral administration of TM5275, a small molecule PAI-1 inhibitor, in APP/PS1 mice upregulated LRP1 expression on what appeared to be endothelial cells, though co-localization studies were not performed to determine cell type specificity78.

Consistently, though, the homeostatic state of the tPA/plasmin system correlates with cognitive ability in AD mouse models. In the Morris water maze, Tg2576/tPA+/− mice spent less time in the target quadrant during the probe trial than their Tg2576/tPA+/+ controls, suggesting a deficit in their ability to form a spatial memory of platform location55. Tg2576/tPA+/− mice also had lower latency times than Tg2576/tPA+/+ controls in a passive avoidance task with retention test, indicating impairments in their long-term (> 24 hours) memory recall. The learning in both the Morris water maze and the passive avoidance task used by Oh et al55 is motivated by aversive stimuli. Prior studies, however, have demonstrated tPA−/− mice to be resistance to stress-induced anxiety-like behavior42, 43. Moreover, multiple studies have established the importance of stress on behavioral performance80, 81; indeed, performance across a range of behavioral domains - valence, arousal, and cognition – (assessed using open-field, and object and social exploration tasks; reward-seeking operant learning tasks; and the Morris water maze) has been shown to be impaired in mice that are genetically susceptible to stress46. Future cognitive tasks, therefore, like novel-object recognition, that are confounded to a lesser degree by stress and are appropriately controlled for, should be considered when assessing cognition in tPA−/− mice. This is especially true for cognitive tasks that are trying to determine the relative contribution of tPA versus AD pathology in learning and memory.

Nonetheless, in agreement with these genetic studies, AD mice treated with pharmacologic inhibitors of PAI-1 have shown improvements in hippocampal-dependent cognitive tasks. Inhibiting PAI-1 appeared to ameliorate deficits in contextual fear conditioning (Tg2576 mice, PAZ-417 inhibitor [Aleplasinin]48), Morris water maze (Tg2576 mice, PAI-039 inhibitor [Tiplaxtinin]77; APP/PS1 mice, TM5275 inhibitor78), and novel object recognition (Tg2576 mice, PAI-03977, 79). Some of these studies implicated reduced Aβ burden from ELISA48 or immunohistochemistry78 analysis of amyloidogenic AD mice treated with PAI-1 inhibitors (via increased tPA/plasmin-mediated clearance) as causal for the observed cognitive improvements48, 78. While other studies, despite observing decreases in Aβ plaque deposition77 or cerebral amyloid angiopathy79, in amyloidogenic AD mice treated with PAI-1 inhibitors, implicated pathways more ancillary to Aβ pathology (e.g. BDNF77 or cerebrovascular79). In human patients with AD, it is highly debated whether Aβ is uniquely responsible for cognitive decline or whether a spectrum of insults – Aβ-dependent and Aβ-independent – is responsible82; clinical trials investigating drugs that target Aβ have largely failed83 and the recent approval of the Aβ-directed monoclonal antibody aducanumab (Aduhelm) by the US Food and Drug Administration is controversial84. Given the current treatment landscape for patients with AD, it’s critical to explore less researched, though viable hypotheses, on AD pathogenesis for future drug development.

One of those hypotheses involves the tPA/plasmin/BDNF pathway, and while evidence is currently limited, it is well-supported for future studies into learning and memory physiology and AD pathogenesis (tPA-mediated cerebrovascular contributions to AD pathogenesis are discussed in detail in a later section). Indeed, the mossy fiber-to-CA3 synaptic circuit (where tPA and BDNF are highly expressed in mossy fiber boutons and where tPA has been shown to modulate synaptic plasticity) is of particular interest as a more recent study demonstrated that forms of neuronal plasticity at the mossy fiber-to-CA3 synapse were impaired in APP/PS1 mice85. Alterations to mossy fiber structure and organization have also been reported in the J20 FAD amyloidogenic AD mouse model, along with synaptic site changes to the thorny excrescences of CA3 dendritic spines86. In addition, functional magnetic resonance imaging has revealed functional and structural changes to the CA3/dentate gyrus region in patients with mild cognitive impairment and AD. While AD patients show decreased activity in CA3/dentate gyrus87, patients with mild cognitive impairment were more likely to have a hyperactive signal in CA3/dentate gyrus, indicating dysfunctional circuitry during disease progression87–89; CA3/dentate gyrus morphology (shape and volume) was also altered in patients with mild cognitive impairment compared to control patients88. It is thought that the cellular physiology underlying CA3 circuitry in the hippocampus is critical for rapid associative learning and contributes to episodic memory90 and impairments in episodic memory are one of the distinctive clinical manifestations of AD in patients91. The effect of the tPA/plasmin/mBDNF cascade on regulating plasticity at the mossy fiber-to-CA3 synapse under physiological conditions, and in the context of AD pathology, remains to be investigated.

Mechanisms of tPA-mediated vascular dysregulation

In addition to the tPA/plasmin/BDNF pathway, there is evidence to suggest that tPA’s role in AD pathogenesis is not related to the clearance of Aβ, but rather, mediated by a plasminogen-independent neurovascular coupling pathway. A role for tPA in neurovascular coupling was demonstrated when mice deficient in tPA, but not plasminogen, were shown to have a reduced functional hyperemia response in the whisker barrel cortex following whisker stimulation92. This response in tPA−/− mice could be restored with topical recombinant tPA treatment to the cortical surface92. As the NR2B subunit of the NMDAR is functionally coupled to neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) it was hypothesized that modulation by tPA altered nNOS-dependent nitric oxide (NO) synthesis and, in turn, cerebral perfusion. To test if this mechanism was responsible for tPA’s effects on blood flow, the cell permeable peptide inhibitor NR2B9c was used to uncouple NMDAR activity from NO production. With NR2B9c treatment, wild-type mice had an attenuated cerebral blood flow response to whisker stimulation, and recombinant tPA no longer rescued the functional hyperemia response in tPA−/− mice.

Given emerging data which suggest a strong contributory, if not causal, role for vascular dysfunction in AD93, 94, tPA’s actions on vascular function were recently investigated in Tg2576 mice79. Similar to tPA−/− mice, Tg2576 mice were found to have an attenuated cerebral blood flow response following whisker stimulation; this attenuated response could be restored with topical application of recombinant tPA. Altered tPA-NMDAR-NO signaling/production was implicated as Tg2576 mice were revealed to have reduced tPA activity and a diminished cerebral blood flow response to NMDA treatment. In addition, dissociated cortical neurons from Tg2576 mice also exhibited enhanced NO production upon co-treatment of NMDA and recombinant tPA, but no response to NMDA treatment alone. Moreover, acute or chronic inhibition of PAI-1, whose activity is upregulated in 3- to 4-month-old Tg2576 mice, with the PAI-1 inhibitor PAI-039 rescued the whisker stimulation-induced cerebral blood flow response in Tg2576 mice, and ameliorated the cognitive deficits typically observed in aged (11- to 12-month-old) Tg2576 mice. Finally, PAI-1−/− mice treated with Aβ1–40 phenocopied the Tg2576 mice treated with PAI-039. Though these data suggest a vasoregulatory role for tPA in AD, chronic PAI-1 inhibition with PAI-039 was also shown to reduce Aβ1–40 levels in the cortex and hippocampus and cortical cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Tg2576 mice. It is unclear, therefore, if the improved cognition and vascular responses with PAI-1 inhibition are a result of reduced Aβ burden or enhanced tPA modulation of the NMDAR/nNos/NO signaling pathway.

These results are further complicated by what appear to be underlying vascular or neurovascular deficiencies innate to the Tg2576 mice in particular and/or AD pathology in general. When treated with topical application of acetylcholine, Tg2576 mice exhibited a decreased cerebral blood flow response compared to their wild-type littermate controls79. Though acetylcholine treatment was intended to test endothelium-dependent vasodilation, acetylcholine receptors are not only present on endothelial cells, but vascular smooth muscle cells and astrocytes as well95–97. Thus, topical treatment of acetylcholine, rather than intravenous infusion, abrogated the ability to test the role of endothelial cells specifically. As such, it is unclear if the deficit in vasoactivity from acetylcholine is specific to the endothelium, or more broadly indicative of altered cholinergic signaling and vascular dysregulation in Tg2576 mice. Moreover, as the authors themselves indicate, Aβ treatment is known to diminish acetylcholine-mediated vasodilation98. Indeed, cholinergic dysregulation is a well-established aspect of AD pathology99. Accordingly, potential changes in the molecular programming of acetylcholine receptors or other receptors/signaling pathways because of altered cholinergic innervation may obfuscate experimental results and make determination of casual actors difficult. Finally, we note that while acetylcholine has been reported to mediate tPA release from the endothelium, the concentrations required for this effect100, 101 are significantly higher than those reported by Park et al79.

Changes in receptor expression and signaling are also important to consider with respect to the NMDAR, the proposed substrate and mediator of tPA’s actions. Like the deficits observed with acetylcholine treatment, there is an attenuated cerebral blood flow response in Tg2576 mice upon NMDA treatment. Park et al79 implicated reduced tPA activity for this attenuation, but it is also possible that altered NMDAR signaling is responsible92. Numerous groups have reported that Aβ downregulates NMDAR surface levels and impairs NMDAR function102–104. Moreover, reverse transcription-PCR analysis of AD brains revealed significantly lower mRNA levels of NMDAR-NR2B, the subunit thought to mediate tPA’s actions105, 106. Complicating this narrative is the fact that Tg2576/tPA+/− mice have decreased protein levels of the NR2B subunits55, suggesting that tPA heterozygosity or that Tg2576 mice themselves display changes in NMDAR subunit expression. It is possible, therefore, that chronic Aβ burden or other underlying molecular changes associated with AD pathology, like altered acetylcholine receptors or NMDAR levels, establish a condition of vascular dysfunction in Tg2576 mice, possibly driving a proportion of the neurovascular coupling deficit attributed to tPA. Future studies examining tPA-mediated NMDAR/nNos/NO signaling should control for changes in NMDAR or acetylcholine receptor expression to determine tPA’s relative contribution to regulating neurovascular coupling.

Interestingly, circulating tPA has also been shown to play a part in potentiating the neurovascular coupling response induced by stimulation of the somatosensory cortex107. Like Park et al92, Anfray and colleagues107 also found tPA−/− mice to have a diminished neurovascular coupling response, albeit to a lesser degree. However, administration of intravenous recombinant tPA, not topical administration to the cortical surface, restored the cerebral blood flow response in tPA−/− mice to a level observed in 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-injected wild-type mice following whisker stimulation107. Though the effects of circulating tPA on neurovascular coupling weren’t investigated in an AD mouse model, another group has shown that chronic intravenous administration of human recombinant tPA (Activase) in APP/PS1 mice correlates with reduced Aβ burden and improved cognition108. It was suggested from in vitro assays that the effects of recombinant tPA were mediated through LRP1 on microglia to enhance mobility and phagocytosis108. As tPA has been shown to cross a diseased BBB (e.g. cerebral ischemia) in vivo109, and an intact BBB in vitro via LRP1110, additional pharmacologic or genetic studies would be informative in discerning circulating tPA’s mechanism of action on neurovascular coupling and AD pathology.

Cumulatively, evidence for tPA-mediated changes in vascular tone is intriguing, especially in the context of Aβ clearance and AD pathogenesis. Perivascular drainage is one of the pathways by which the brain clears metabolic waste products, like Aβ111, 112, and there is accumulating evidence to suggest that the motive forces driving perivascular drainage are intrinsic to the cerebral arteries (i.e., vasocontraction and vasodilation)113, 114. And, while perivascular drainage wasn’t explicitly investigated, vascular abnormalities, including altered blood vessel morphology, increased blood vessel number and density, and obstructed blood flow, were observed in the Tg4510 tauopathy AD mouse model73. Increased endothelial cell PAI-1 expression was implicated in these vascular remodeling changes as PAI-1 mRNA and protein were found to be significantly upregulated73. Targeting tPA-mediated signaling pathways – whether upstream or downstream or through direct or indirect interaction with Aβ and/or tau – may provide novel therapeutic benefit against AD-related pathologies, and possibly, slow disease progression.

Future investigations into the vascular contribution to AD pathology

tPA-mediated BBB dysregulation as a therapeutic target

The data described above clearly indicate a vascular component to AD pathology. Indeed, BBB dysfunction is now a well-established feature in AD115, 116. And, while tPA has not been directly implicated in BBB dysfunction in AD, there is evidence to suggest a critical role for tPA in regulating BBB permeability in other pathologies5, 117–120. In the context of BBB regulation, tPA appears to act through cleavage of platelet-derived growth factor-CC (PDGF-CC) and subsequent activation of the PDGFR-α in the neurovascular unit. Blocking the tPA/PDGF-CC/PDGFRα signaling pathway with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor Imatinib preserves barrier function and improves outcome in models of stroke, seizure, and traumatic brain injury5, 117, 120.

While this pathway has been validated in multiple models of BBB dysfunction, earlier efforts to discern tPA/plasmin’s actions on the BBB in stroke implicated matrix metalloproteinase 9121, 122. Though the mechanism and cellular source of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in stroke and BBB damage is still controversial123, 124, numerous studies have demonstrated that neutrophils infiltrating the brain parenchyma are the main source of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in the later stages of stroke and BBB damage125, 126

The tPA/PDGF-CC/PDGFRα signaling pathway, however, appears to be activated during the early phases of BBB opening post-stroke5, 127; moreover, it is now appreciated that the integrin MAC-1 (macrophage-1 antigen; also known as αMβ2 and CD11b/CD18) on resident microglia acts as a co-factor for tPA to accelerate cleavage of PDGF-CC127. While earlier biochemical work had shown tPA to be an inefficient enzyme, compared to other serine proteases128, the activity of tPA can be greatly enhanced by co-factors, like fibrin(ogen) or Aβ57. Accordingly, Su et al127 hypothesized that there existed some unknown co-factor in the neurovascular unit that was facilitating tPA’s cleavage of PDGF-CC; in a series of in vitro and in vivo model systems, both LRP1 and MAC-1 were shown to be necessary and sufficient in facilitating activation of PDGF-CC by tPA.

That tPA activity is significantly increased by MAC-1, fibrin(ogen), or Aβ is of note as these proteins intersect at the BBB in the context of AD. In post-mortem tissue from human AD patients and mouse models of AD, fibrin(ogen), which is normally compartmentalized to the vasculature, is detected in the intra- and extravascular space12, 129–131. Extravasated fibrin(ogen) appears to induce microglia activation and generation of reactive oxygen species, which result in neurodegeneration and cognitive deficits in the 5×FAD amyloidogenic AD mouse model132. This neuroinflammatory response is mediated by MAC-1, as genetic loss of the cd11b integrin of MAC-1 disrupts fibrin(ogen)-induced microglia activation and prevents neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment. Indeed, treatment with the novel monoclonal antibody 5B8, which inhibits fibrin-induced inflammation and oxidative stress, protected 5×FAD mice from cholinergic neuron loss and aberrant inflammation12. The role of tPA and the downstream PDGF-CC/PDGFRα signaling cascade in potentiating BBB opening, and contributing to further fibrin(ogen) extravasation, was not examined in these studies.

Preserving BBB function with Imatinib treatment has been shown to be therapeutically beneficial in other mouse models of neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory disorders. In a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Imatinib treatment restored integrity of the brain spinal cord barrier and delayed amyotrophic lateral sclerosis onset119, while rats and mice with autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a model of multiple sclerosis, had improved barrier function and autoimmune encephalomyelitis symptoms after Imatinib treatment118, 133. Because of the promising preclinical data on Imatinib, clinical trials in the United States and Europe are currently investigating Imatinib treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03674099) and stroke (EudraCT Number: 2010–019014-25). The congruity of the tPA/PDGF-CC/PDGFRα pathway across disease model systems suggests that this pathway is a conserved, common regulator of BBB permeability. Targeting this pathway to preserve barrier integrity, along with other downstream effectors of vascular dysfunction, could have an additive therapeutic benefit for the treatment of AD.

Conclusions

It has been 40 years since Krystosek and Seeds134 were the first to demonstrate a non-fibrinolytic role for the plasminogen activation system in the CNS, and it has been almost 30 years since tPA was first implicated as an immediate-early gene involved in learning and memory1. Though many questions remain, progress has been made in elucidating tPA’s physiological role in synaptic plasticity and its pathological role in AD. While early work on the tPA/plasmin system in AD models focused on Aβ clearance and degradation, more recent studies have explored mechanisms of tPA-mediated vascular dysregulation. In addition to these studies demonstrating a role for tPA in cerebrovascular pathologies associated with AD, they highlight a growing body of evidence and appreciation for how vascular dysfunction is a key pathogenic contributor to AD. Understanding how tPA and other proteins are involved in vascular dysfunction is critical for developing new druggable targets to treat AD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL055374, and NS079639 (D.A.L), NS007222 (T.K.S), and AG052934 and The University of Michigan Protein Folding Disease Initiative (S.J.M and G.G.M).

Conflict of interest:

D.A.L is a founder and holds equity in MDI Therapeutics which has an option to license PAI-1 inhibitory compounds from the University of Michigan; TKS, SJM, and GGM declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Qian Z, Gilbert ME, Colicos MA, Kandel ER, Kuhl D. Tissue-plasminogen activator is induced as an immediate-early gene during seizure, kindling and long-term potentiation. Nature. Feb 4 1993;361(6411):453–7. doi: 10.1038/361453a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seeds NW, Williams BL, Bickford PC. Tissue plasminogen activator induction in Purkinje neurons after cerebellar motor learning. Science. Dec 22 1995;270(5244):1992–4. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsirka SE, Gualandris A, Amaral DG, Strickland S. Excitotoxin-induced neuronal degeneration and seizure are mediated by tissue plasminogen activator. Nature. Sep 28 1995;377(6547):340–4. doi: 10.1038/377340a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen ZL, Strickland S. Neuronal death in the hippocampus is promoted by plasmin-catalyzed degradation of laminin. Cell. Dec 26 1997;91(7):917–25. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80483-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su EJ, Fredriksson L, Geyer M, et al. Activation of PDGF-CC by tissue plasminogen activator impairs blood-brain barrier integrity during ischemic stroke. Nat Med. Jul 2008;14(7):731–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matys T, Strickland S. Tissue plasminogen activator and NMDA receptor cleavage. Nat Med. Apr 2003;9(4):371–2; author reply 372–3. doi: 10.1038/nm0403-371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samson AL, Nevin ST, Croucher D, et al. Tissue-type plasminogen activator requires a co-receptor to enhance NMDA receptor function. J Neurochem. Nov 2008;107(4):1091–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05687.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pang PT, Teng HK, Zaitsev E, et al. Cleavage of proBDNF by tPA/plasmin is essential for long-term hippocampal plasticity. Science. Oct 15 2004;306(5695):487–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1100135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polanco JC, Li C, Bodea LG, Martinez-Marmol R, Meunier FA, Gotz J. Amyloid-beta and tau complexity - towards improved biomarkers and targeted therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. Jan 2018;14(1):22–39. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strickland S. Blood will out: vascular contributions to Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Invest. Feb 1 2018;128(2):556–563. doi: 10.1172/JCI97509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding J, Davis-Plourde KL, Sedaghat S, et al. Antihypertensive medications and risk for incident dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies. Lancet Neurol. Jan 2020;19(1):61–70. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30393-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryu JK, Rafalski VA, Meyer-Franke A, et al. Fibrin-targeting immunotherapy protects against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Nat Immunol. Nov 2018;19(11):1212–1223. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0232-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frey U, Muller M, Kuhl D. A different form of long-lasting potentiation revealed in tissue plasminogen activator mutant mice. J Neurosci. Mar 15 1996;16(6):2057–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabresi P, Napolitano M, Centonze D, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator controls multiple forms of synaptic plasticity and memory. Eur J Neurosci. Mar 2000;12(3):1002–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00991.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang YY, Bach ME, Lipp HP, et al. Mice lacking the gene encoding tissue-type plasminogen activator show a selective interference with late-phase long-term potentiation in both Schaffer collateral and mossy fiber pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Aug 6 1996;93(16):8699–704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhuo M, Holtzman DM, Li Y, et al. Role of tissue plasminogen activator receptor LRP in hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. Jan 15 2000;20(2):542–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu F, Torre E, Cuellar-Giraldo D, et al. Tissue-type plasminogen activator triggers the synaptic vesicle cycle in cerebral cortical neurons. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Dec 2015;35(12):1966–76. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz A, Jeanneret V, Merino P, McCann P, Yepes M. Tissue-type plasminogen activator regulates p35-mediated Cdk5 activation in the postsynaptic terminal. J Cell Sci. Feb 28 2019;132(5)doi: 10.1242/jcs.224196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeanneret V, Wu F, Merino P, et al. Tissue-type Plasminogen Activator (tPA) Modulates the Postsynaptic Response of Cerebral Cortical Neurons to the Presynaptic Release of Glutamate. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016;9:121. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chater TE, Goda Y. The role of AMPA receptors in postsynaptic mechanisms of synaptic plasticity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:401. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bianchetta MJ, Lam TT, Jones SN, Morabito MA. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 regulates PSD-95 ubiquitination in neurons. J Neurosci. Aug 17 2011;31(33):12029–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2388-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baranes D, Lederfein D, Huang YY, Chen M, Bailey CH, Kandel ER. Tissue plasminogen activator contributes to the late phase of LTP and to synaptic growth in the hippocampal mossy fiber pathway. Neuron. Oct 1998;21(4):813–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80597-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madani R, Hulo S, Toni N, et al. Enhanced hippocampal long-term potentiation and learning by increased neuronal expression of tissue-type plasminogen activator in transgenic mice. EMBO J. Jun 1 1999;18(11):3007–12. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medcalf RL, Ruegg M, Schleuning WD. A DNA motif related to the cAMP-responsive element and an exon-located activator protein-2 binding site in the human tissue-type plasminogen activator gene promoter cooperate in basal expression and convey activation by phorbol ester and cAMP. J Biol Chem. Aug 25 1990;265(24):14618–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abel T, Nguyen PV, Barad M, Deuel TA, Kandel ER, Bourtchouladze R. Genetic demonstration of a role for PKA in the late phase of LTP and in hippocampus-based long-term memory. Cell. Mar 7 1997;88(5):615–26. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81904-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu K, Yang J, Tanaka S, Gonias SL, Mars WM, Liu Y. Tissue-type plasminogen activator acts as a cytokine that triggers intracellular signal transduction and induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene expression. J Biol Chem. Jan 27 2006;281(4):2120–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504988200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korte M, Carroll P, Wolf E, Brem G, Thoenen H, Bonhoeffer T. Hippocampal long-term potentiation is impaired in mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Sep 12 1995;92(19):8856–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korte M, Kang H, Bonhoeffer T, Schuman E. A role for BDNF in the late-phase of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Neuropharmacology. Apr-May 1998;37(4–5):553–9. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00035-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minichiello L, Calella AM, Medina DL, Bonhoeffer T, Klein R, Korte M. Mechanism of TrkB-mediated hippocampal long-term potentiation. Neuron. Sep 26 2002;36(1):121–37. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00942-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu B, Gottschalk W, Chow A, et al. The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor receptors in the mature hippocampus: modulation of long-term potentiation through a presynaptic mechanism involving TrkB. J Neurosci. Sep 15 2000;20(18):6888–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee R, Kermani P, Teng KK, Hempstead BL. Regulation of cell survival by secreted proneurotrophins. Science. Nov 30 2001;294(5548):1945–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1065057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scalettar BA, Jacobs C, Fulwiler A, et al. Hindered submicron mobility and long-term storage of presynaptic dense-core granules revealed by single-particle tracking. Dev Neurobiol. Sep 2012;72(9):1181–95. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conner JM, Lauterborn JC, Yan Q, Gall CM, Varon S. Distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein and mRNA in the normal adult rat CNS: evidence for anterograde axonal transport. J Neurosci. Apr 1 1997;17(7):2295–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan Q, Rosenfeld RD, Matheson CR, et al. Expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein in the adult rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. May 1997;78(2):431–48. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00613-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danzer SC, McNamara JO. Localization of brain-derived neurotrophic factor to distinct terminals of mossy fiber axons implies regulation of both excitation and feedforward inhibition of CA3 pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. Dec 15 2004;24(50):11346–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3846-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevenson TK, Lawrence DA. Characterization of Tissue Plasminogen Activator Expression and Trafficking in the Adult Murine Brain. eNeuro. Jul-Aug 2018;5(4)doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0119-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rollenhagen A, Lubke JH. The mossy fiber bouton: the “common” or the “unique” synapse? Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2010;2:2. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Acsady L, Kamondi A, Sik A, Freund T, Buzsaki G. GABAergic cells are the major postsynaptic targets of mossy fibers in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. May 1 1998;18(9):3386–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pawlak R, Nagai N, Urano T, et al. Rapid, specific and active site-catalyzed effect of tissue-plasminogen activator on hippocampus-dependent learning in mice. Neuroscience. 2002;113(4):995–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00166-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguiz RM, Wetsel WC. Assessments of Cognitive Deficits in Mutant Mice. In: Levin ED, Buccafusco JJ, eds. Animal Models of Cognitive Impairment. 2006. Frontiers in Neuroscience. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim EJ, Pellman B, Kim JJ. Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review. Learn Mem. Sep 2015;22(9):411–6. doi: 10.1101/lm.037291.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pawlak R, Magarinos AM, Melchor J, McEwen B, Strickland S. Tissue plasminogen activator in the amygdala is critical for stress-induced anxiety-like behavior. Nat Neurosci. Feb 2003;6(2):168–74. doi: 10.1038/nn998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matys T, Pawlak R, Matys E, Pavlides C, McEwen BS, Strickland S. Tissue plasminogen activator promotes the effects of corticotropin-releasing factor on the amygdala and anxiety-like behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Nov 16 2004;101(46):16345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407355101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas GM, Huganir RL. MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. Mar 2004;5(3):173–83. doi: 10.1038/nrn1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennur S, Shankaranarayana Rao BS, Pawlak R, Strickland S, McEwen BS, Chattarji S. Stress-induced spine loss in the medial amygdala is mediated by tissue-plasminogen activator. Neuroscience. Jan 5 2007;144(1):8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez G, Moore SJ, Neff RC, et al. Deficits across multiple behavioral domains align with susceptibility to stress in 129S1/SvImJ mice. Neurobiol Stress. Nov 2020;13:100262. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore SJ, Deshpande K, Stinnett GS, Seasholtz AF, Murphy GG. Conversion of short-term to long-term memory in the novel object recognition paradigm. Neurobiol Learn Mem. Oct 2013;105:174–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobsen JS, Comery TA, Martone RL, et al. Enhanced clearance of Abeta in brain by sustaining the plasmin proteolysis cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jun 24 2008;105(25):8754–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710823105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Nostrand WE, Porter M. Plasmin cleavage of the amyloid beta-protein: alteration of secondary structure and stimulation of tissue plasminogen activator activity. Biochemistry. Aug 31 1999;38(35):11570–6. doi: 10.1021/bi990610f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ledesma MD, Da Silva JS, Crassaerts K, Delacourte A, De Strooper B, Dotti CG. Brain plasmin enhances APP alpha-cleavage and Abeta degradation and is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease brains. EMBO Rep. Dec 2000;1(6):530–5. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tucker HM, Kihiko M, Caldwell JN, et al. The plasmin system is induced by and degrades amyloid-beta aggregates. J Neurosci. Jun 1 2000;20(11):3937–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tucker HM, Kihiko-Ehmann M, Wright S, Rydel RE, Estus S. Tissue plasminogen activator requires plasminogen to modulate amyloid-beta neurotoxicity and deposition. J Neurochem. Nov 2000;75(5):2172–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752172.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melchor JP, Pawlak R, Strickland S. The tissue plasminogen activator-plasminogen proteolytic cascade accelerates amyloid-beta (Abeta) degradation and inhibits Abeta-induced neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. Oct 1 2003;23(26):8867–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu RM, van Groen T, Katre A, et al. Knockout of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 gene reduces amyloid beta peptide burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. Jun 2011;32(6):1079–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oh SB, Byun CJ, Yun JH, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator arrests Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging. Mar 2014;35(3):511–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, et al. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. Aug 2015;11(8):457–70. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kingston IB, Castro MJ, Anderson S. In vitro stimulation of tissue-type plasminogen activator by Alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide analogues. Nat Med. Feb 1995;1(2):138–42. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wnendt S, Wetzels I, Gunzler WA. Amyloid beta peptides stimulate tissue-type plasminogen activator but not recombinant prourokinase. Thromb Res. Feb 1 1997;85(3):217–24. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(97)00006-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kranenburg O, Bouma B, Kroon-Batenburg LM, et al. Tissue-type plasminogen activator is a multiligand cross-beta structure receptor. Curr Biol. Oct 29 2002;12(21):1833–9. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01224-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kruithof EK, Schleuning WD. A comparative study of amyloid-beta (1–42) as a cofactor for plasminogen activation by vampire bat plasminogen activator and recombinant human tissue-type plasminogen activator. Thromb Haemost. Sep 2004;92(3):559–67. doi: 10.1160/TH04-02-0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rebeck GW, Harr SD, Strickland DK, Hyman BT. Multiple, diverse senile plaque-associated proteins are ligands of an apolipoprotein E receptor, the alpha 2-macroglobulin receptor/low-density-lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Ann Neurol. Feb 1995;37(2):211–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qiu Z, Strickland DK, Hyman BT, Rebeck GW. Alpha2-macroglobulin enhances the clearance of endogenous soluble beta-amyloid peptide via low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein in cortical neurons. J Neurochem. Oct 1999;73(4):1393–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bu G, Maksymovitch EA, Nerbonne JM, Schwartz AL. Expression and function of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) in mammalian central neurons. J Biol Chem. Jul 15 1994;269(28):18521–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang L, Liu CC, Zheng H, et al. LRP1 modulates the microglial immune response via regulation of JNK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. J Neuroinflammation. Dec 8 2016;13(1):304. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0772-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu CC, Hu J, Zhao N, et al. Astrocytic LRP1 Mediates Brain Abeta Clearance and Impacts Amyloid Deposition. J Neurosci. Apr 12 2017;37(15):4023–4031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3442-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Storck SE, Meister S, Nahrath J, et al. Endothelial LRP1 transports amyloid-beta(1–42) across the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest. Jan 2016;126(1):123–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI81108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanekiyo T, Liu CC, Shinohara M, Li J, Bu G. LRP1 in brain vascular smooth muscle cells mediates local clearance of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta. J Neurosci. Nov 14 2012;32(46):16458–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3987-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kanekiyo T, Cirrito JR, Liu CC, et al. Neuronal clearance of amyloid-beta by endocytic receptor LRP1. J Neurosci. Dec 4 2013;33(49):19276–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3487-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma Q, Zhao Z, Sagare AP, et al. Blood-brain barrier-associated pericytes internalize and clear aggregated amyloid-beta42 by LRP1-dependent apolipoprotein E isoform-specific mechanism. Mol Neurodegener. Oct 19 2018;13(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13024-018-0286-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fujiyoshi M, Tachikawa M, Ohtsuki S, et al. Amyloid-beta peptide(1–40) elimination from cerebrospinal fluid involves low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 at the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. J Neurochem. Aug 2011;118(3):407–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07311.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamamoto K, Takeshita K, Saito H. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in aging. Semin Thromb Hemost. Sep 2014;40(6):652–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1384635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cacquevel M, Launay S, Castel H, et al. Ageing and amyloid-beta peptide deposition contribute to an impaired brain tissue plasminogen activator activity by different mechanisms. Neurobiol Dis. Aug 2007;27(2):164–73. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bennett RE, Robbins AB, Hu M, et al. Tau induces blood vessel abnormalities and angiogenesis-related gene expression in P301L transgenic mice and human Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Feb 6 2018;115(6):E1289–E1298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710329115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Newcombe EA, Camats-Perna J, Silva ML, Valmas N, Huat TJ, Medeiros R. Inflammation: the link between comorbidities, genetics, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. Sep 24 2018;15(1):276. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1313-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Killin LO, Starr JM, Shiue IJ, Russ TC. Environmental risk factors for dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. Oct 12 2016;16(1):175. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0342-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Van Cauwenberghe C, Van Broeckhoven C, Sleegers K. The genetic landscape of Alzheimer disease: clinical implications and perspectives. Genet Med. May 2016;18(5):421–30. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gerenu G, Martisova E, Ferrero H, et al. Modulation of BDNF cleavage by plasminogen-activator inhibitor-1 contributes to Alzheimer’s neuropathology and cognitive deficits. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. Apr 2017;1863(4):991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Akhter H, Huang WT, van Groen T, Kuo HC, Miyata T, Liu RM. A Small Molecule Inhibitor of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Reduces Brain Amyloid-beta Load and Improves Memory in an Animal Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(2):447–457. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Park L, Zhou J, Koizumi K, et al. tPA Deficiency Underlies Neurovascular Coupling Dysfunction by Amyloid-beta. J Neurosci. Oct 14 2020;40(42):8160–8173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1140-20.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lopez SA, Flagel SB. A proposed role for glucocorticoids in mediating dopamine-dependent cue-reward learning. Stress. Mar 2021;24(2):154–167. doi: 10.1080/10253890.2020.1768240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Daviu N, Bruchas MR, Moghaddam B, Sandi C, Beyeler A. Neurobiological links between stress and anxiety. Neurobiol Stress. Nov 2019;11:100191. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Makin S. The amyloid hypothesis on trial. Nature. Jul 2018;559(7715):S4–S7. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05719-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oxford AE, Stewart ES, Rohn TT. Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Hurdle in the Path of Remedy. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;2020:5380346. doi: 10.1155/2020/5380346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mullard A. Controversial Alzheimer’s drug approval could affect other diseases. Nature. Jul 2021;595(7866):162–163. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01763-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Viana da Silva S, Zhang P, Haberl MG, et al. Hippocampal Mossy Fibers Synapses in CA3 Pyramidal Cells Are Altered at an Early Stage in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurosci. May 22 2019;39(21):4193–4205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2868-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wilke SA, Raam T, Antonios JK, et al. Specific disruption of hippocampal mossy fiber synapses in a mouse model of familial Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sperling R. Functional MRI studies of associative encoding in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Feb 2007;1097:146–55. doi: 10.1196/annals.1379.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yassa MA, Stark SM, Bakker A, Albert MS, Gallagher M, Stark CE. High-resolution structural and functional MRI of hippocampal CA3 and dentate gyrus in patients with amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. Neuroimage. Jul 1 2010;51(3):1242–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Setti SE, Hunsberger HC, Reed MN. Alterations in Hippocampal Activity and Alzheimer’s Disease. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. Dec 2017;3(4):348–356. doi: 10.1037/tps0000124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kesner RP, Rolls ET. A computational theory of hippocampal function, and tests of the theory: new developments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. Jan 2015;48:92–147. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gallagher M, Koh MT. Episodic memory on the path to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. Dec 2011;21(6):929–34. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Park L, Gallo EF, Anrather J, et al. Key role of tissue plasminogen activator in neurovascular coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jan 22 2008;105(3):1073–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708823105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iturria-Medina Y, Sotero RC, Toussaint PJ, Mateos-Perez JM, Evans AC, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Early role of vascular dysregulation on late-onset Alzheimer’s disease based on multifactorial data-driven analysis. Nat Commun. Jun 21 2016;7:11934. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Snyder HM, Corriveau RA, Craft S, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia including Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. Jun 2015;11(6):710–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Beach TG, Potter PE, Kuo YM, et al. Cholinergic deafferentation of the rabbit cortex: a new animal model of Abeta deposition. Neurosci Lett. Mar 31 2000;283(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00916-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clifford PM, Siu G, Kosciuk M, et al. Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression by vascular smooth muscle cells facilitates the deposition of Abeta peptides and promotes cerebrovascular amyloid angiopathy. Brain Res. Oct 9 2008;1234:158–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hamel E. Perivascular nerves and the regulation of cerebrovascular tone. J Appl Physiol (1985). Mar 2006;100(3):1059–64. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00954.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thomas T, Thomas G, McLendon C, Sutton T, Mullan M. beta-Amyloid-mediated vasoactivity and vascular endothelial damage. Nature. Mar 14 1996;380(6570):168–71. doi: 10.1038/380168a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grothe M, Heinsen H, Teipel SJ. Atrophy of the cholinergic Basal forebrain over the adult age range and in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. May 1 2012;71(9):805–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Minai K, Matsumoto T, Horie H, et al. Bradykinin stimulates the release of tissue plasminogen activator in human coronary circulation: effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. May 2001;37(6):1565–70. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01202-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Klocking HP. Release of plasminogen activator by acetylcholine from the isolated perfused pig ear. Thromb Res. 1979;16(1–2):261–4. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(79)90287-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Parameshwaran K, Dhanasekaran M, Suppiramaniam V. Amyloid beta peptides and glutamatergic synaptic dysregulation. Exp Neurol. Mar 2008;210(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Goto Y, Niidome T, Akaike A, Kihara T, Sugimoto H. Amyloid beta-peptide preconditioning reduces glutamate-induced neurotoxicity by promoting endocytosis of NMDA receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. Dec 8 2006;351(1):259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, et al. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci. Aug 2005;8(8):1051–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bi H, Sze CI. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit NR2A and NR2B messenger RNA levels are altered in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. Aug 15 2002;200(1–2):11–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00087-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hynd MR, Scott HL, Dodd PR. Differential expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor NR2 isoforms in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. Aug 2004;90(4):913–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02548.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Anfray A, Drieu A, Hingot V, et al. Circulating tPA contributes to neurovascular coupling by a mechanism involving the endothelial NMDA receptors. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Oct 2020;40(10):2038–2054. doi: 10.1177/0271678X19883599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.ElAli A, Bordeleau M, Theriault P, Filali M, Lampron A, Rivest S. Tissue-Plasminogen Activator Attenuates Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Pathology Development in APPswe/PS1 Mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. Apr 2016;41(5):1297–307. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang YF, Tsirka SE, Strickland S, Stieg PE, Soriano SG, Lipton SA. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) increases neuronal damage after focal cerebral ischemia in wild-type and tPA-deficient mice. Nat Med. Feb 1998;4(2):228–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Benchenane K, Berezowski V, Ali C, et al. Tissue-type plasminogen activator crosses the intact blood-brain barrier by low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-mediated transcytosis. Circulation. May 3 2005;111(17):2241–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163542.48611.A2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wojtas AM, Kang SS, Olley BM, et al. Loss of clusterin shifts amyloid deposition to the cerebrovasculature via disruption of perivascular drainage pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Aug 15 2017;114(33):E6962–E6971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701137114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Carare RO, Bernardes-Silva M, Newman TA, et al. Solutes, but not cells, drain from the brain parenchyma along basement membranes of capillaries and arteries: significance for cerebral amyloid angiopathy and neuroimmunology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. Apr 2008;34(2):131–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schley D, Carare-Nnadi R, Please CP, Perry VH, Weller RO. Mechanisms to explain the reverse perivascular transport of solutes out of the brain. J Theor Biol. Feb 21 2006;238(4):962–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Aldea R, Weller RO, Wilcock DM, Carare RO, Richardson G. Cerebrovascular Smooth Muscle Cells as the Drivers of Intramural Periarterial Drainage of the Brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:1. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cai Z, Qiao PF, Wan CQ, Cai M, Zhou NK, Li Q. Role of Blood-Brain Barrier in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(4):1223–1234. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Montagne A, Zhao Z, Zlokovic BV. Alzheimer’s disease: A matter of blood-brain barrier dysfunction? J Exp Med. Nov 6 2017;214(11):3151–3169. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fredriksson L, Stevenson TK, Su EJ, et al. Identification of a neurovascular signaling pathway regulating seizures in mice. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. Jul 2015;2(7):722–38. doi: 10.1002/acn3.209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zeitelhofer M, Adzemovic MZ, Moessinger C, et al. Blocking PDGF-CC signaling ameliorates multiple sclerosis-like neuroinflammation by inhibiting disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Sci Rep. Dec 24 2020;10(1):22383. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79598-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lewandowski SA, Nilsson I, Fredriksson L, et al. Presymptomatic activation of the PDGF-CC pathway accelerates onset of ALS neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. Mar 2016;131(3):453–64. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1520-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Su EJ, Fredriksson L, Kanzawa M, et al. Imatinib treatment reduces brain injury in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:385. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Asahi M, Asahi K, Jung JC, del Zoppo GJ, Fini ME, Lo EH. Role for matrix metalloproteinase 9 after focal cerebral ischemia: effects of gene knockout and enzyme inhibition with BB-94. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Dec 2000;20(12):1681–9. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200012000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Asahi M, Wang X, Mori T, et al. Effects of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out on the proteolysis of blood-brain barrier and white matter components after cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. Oct 1 2001;21(19):7724–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Turner RJ, Sharp FR. Implications of MMP9 for Blood Brain Barrier Disruption and Hemorrhagic Transformation Following Ischemic Stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016;10:56. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yepes M, Sandkvist M, Moore EG, Bugge TH, Strickland DK, Lawrence DA. Tissue-type plasminogen activator induces opening of the blood-brain barrier via the LDL receptor-related protein. J Clin Invest. Nov 2003;112(10):1533–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI19212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Justicia C, Panes J, Sole S, et al. Neutrophil infiltration increases matrix metalloproteinase-9 in the ischemic brain after occlusion/reperfusion of the middle cerebral artery in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. Dec 2003;23(12):1430–40. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000090680.07515.C8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gidday JM, Gasche YG, Copin JC, et al. Leukocyte-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates blood-brain barrier breakdown and is proinflammatory after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. Aug 2005;289(2):H558–68. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01275.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Su EJ, Cao C, Fredriksson L, et al. Microglial-mediated PDGF-CC activation increases cerebrovascular permeability during ischemic stroke. Acta Neuropathol. Oct 2017;134(4):585–604. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1749-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Fredriksson L, Li H, Fieber C, Li X, Eriksson U. Tissue plasminogen activator is a potent activator of PDGF-CC. EMBO J. Oct 1 2004;23(19):3793–802. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cortes-Canteli M, Mattei L, Richards AT, Norris EH, Strickland S. Fibrin deposited in the Alzheimer’s disease brain promotes neuronal degeneration. Neurobiol Aging. Feb 2015;36(2):608–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cortes-Canteli M, Paul J, Norris EH, et al. Fibrinogen and beta-amyloid association alters thrombosis and fibrinolysis: a possible contributing factor to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. Jun 10 2010;66(5):695–709. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]