Abstract

Child screen media use may cause family conflict, and risk factors for such conflict are not well characterized. This study examined risk factors of persistent requesting to use screen media among preschool-age children, focusing on parent-reported characteristics of parent and child screen media use. Data was collected through an online survey completed in 2017 by a nationally recruited sample of 383 parents of 2–5-year-old children. Parents reported on their child’s and their own screen media use, household/sociodemographic measures, and child requests to use screen media. Persistent requesting was defined as exhibiting “bothersome” or “very bothersome” behaviors to use screen media. Poisson regression with robust standard errors computed the prevalence risk ratio of persistent requests on parent and child screen media use characteristics, adjusted for household and sociodemographic characteristics. Overall, based on parents’ reports, 28.7% of children exhibited persistent requesting, which was often accompanied by whining, crying, gesturing, or physically taking a device. In an adjusted regression model, higher amounts of parental time spent using social media, but not parental time spent using other screen media, was associated with a greater prevalence of children’s persistent requests. In latter models, children’s use of smartphones and engagement with online videos were independently related to persistent requests. Across all models, children’s total quantity of screen media use was unrelated to persistent requests. Practitioners advising families on managing conflict around child screen media use should consider characteristics of both child and parent screen media use.

Keywords: Smartphone usage, Social media, Parent-child interactions, Screen media, Online videos, Household chaos, Electronic devices, Children, Parenting, Household rules

Introduction

Screen media use is a common activity among preschool-age children (i.e., 2–5 years old), who now engage with screens for an average of 2.5 hours daily in the US (Rideout et al., 2017). In contrast to this daily usage, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no more than 1 hour per day of high-quality screen activities for children of this age (2016). Although there are positive uses of technology (e.g., using video chat to connect young children with family members; prosocial or educational media that can foster social-emotional skills, e.g., Rasmussen et al., 2016), a bulk of research has examined how excessive screen media use in early childhood may negatively affect child growth and development, yet there is an increasing need to understand how screen media use affects parenting and the parent-child relationship (Stiglic & Viner, 2019). For example, while many parents report that screens are helpful in occupying children or managing their behavior, transitioning children away from screen media can be challenging (Hiniker et al., 2016; Rideout et al., 2017; Wartella et al., 2014).

In a 2014 nationally representative survey, 21% of parents with young children (birth to 8 years of age) reported that negotiation of screen use limits between parent and child is a cause of household conflict (Wartella et al., 2014). A recent study also found that negotiating around screen media use limits was a common practice among family members, including preschool-age children (Domoff et al., 2019). Children are active in bargaining and negotiating which devices they can use and when, while parents often experience multiple sources of conflict concerning management of family screen media use, including the challenge of increasingly available technology and children’s often superior knowledge of screen devices (Beyens & Beullens, 2017; Hiniker et al., 2016). Prior research has found that early exposure to television increases the risk for children protesting limits on time allowed for viewing, while other research reports that the total quantity of time young children spend engaging with screens is positively related to this screen media use conflict (Beyens & Beullens, 2017; Wartella et al., 2014). However, it remains unclear if specific characteristics of contemporary media uniquely impact tension around children’s screen media use. Additionally, there is a lack of understanding of how parental screen media use habits, including their own engagement with screens, may affect conflict around screen media use limits for children.

Children naturally challenge parents during the preschool years as they learn to navigate boundaries (Schneider-Rosen & Wenz-Gross, 1990). Because excessive screen media use may have detrimental effects on development during this time, understanding factors related to conflict about limits will facilitate identification of strategies for parents to manage these activities with less dissension. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine risk factors for insistent requests to use screen media among preschool-age children, which we refer to as “persistent requesting,” with a specific focus on characteristics of child and parent screen media use.

Methods

Study Design

Data came from a survey of parents recruited nationally via social media to examine household factors associated with young children’s screen media use (Emond et al., 2018). More than 70% of parents in the US use social media, and samples recruited via social media are often more generalizable as compared to study samples recruited locally (Duggan et al., 2015; Whitaker et al., 2017). For recruitment, advertisements targeted to parents of preschoolers were purchased on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram during a 5-week period from June to August 2017. Parents who clicked the recruitment advertisements were directed to a secure website to complete a brief screening questionnaire; recruitment advertisements did not disclose the study’s intent. Study eligibility included being a parent or guardian of a child aged 2–5 years, living with that child at least 50% of the time, and being knowledgeable about that child’s weekly TV use. Parents who completed the survey could enroll in a raffle for one of 20 $50 gift cards to a popular online vendor. All parents provided electronic consent, and the study was approved by the [university’s institutional review board].

Measures

Child requests to use screen media.

Parents were asked, Does your child ever ask you to use media devices, even after you’ve said no (yes versus no)? Parents who answered yes were then asked, How bothersome is it when your child asks you to use media devices, even after you’ve said no? Response options were not at all bothersome, a little bothersome, bothersome or very bothersome. Responses of bothersome or very bothersome were combined to indicate persistent requesting to use media devices. In contrast, children who did not ask to use media devices after the parent denied the request, or responses of not all bothersome or a little bothersome, were all combined to indicate no requesting/non-persistent requesting. Parents then reported on four behaviors their child might display when asking to use screen media after the parent denied their request: whining, crying, making physical gestures like stomping his/her feet or making fists, and physically taking a device on his/her own. Responses to each item were never, rarely, sometimes, or a lot, and each item was dichotomized as sometimes or a lot versus never or rarely to describe the prevalence of each requesting behavior.

Children’s screen media use.

Parents completed a series of questions regarding their children’s typical screen media use in the past few months (Rideout et al., 2010). Parents reported on their child’s use of seven screen devices in the past 3 months (yes versus no): traditional TV, smartphones, touchscreen tablets made for adults, child-specific touchscreen tablets, desktop/laptop computers, video game consoles, and handheld videogames. Few (3.1%) children used a handheld video game device; as such, video game consoles or handheld video game devices were combined into one category.

Parents also reported which screen media activities their child engaged in (yes versus no), with the following activities being included in the analysis: watching TV programs or movies, playing or engaging with “apps”, watching online videos or clips other than shows or movies (e.g. YouTube), and playing video games on the Internet. We asked about but did not include in our analyses: listening to or streaming music, browsing or “reading” electronic books or magazines, or video conferencing. This was due to these activities being quite distinct from screen-based media consumption. A sensitivity analysis was conducted including those activities, indicating that they were not associated with persistent requesting, while all other results were essentially unchanged. We also asked about, but did not include, engaging in social media (alone or with another) or browsing websites, because few children (n=5 and n=8, respectively) engaged in those activities.

Parents reported on the hours per day their child spent on each screen media activity on a typical weekday and a typical weekend day. Values for each day were summed and a weighted average (5/7*weekday use+2/7*weekend day use) was created to reflect children’s total screen media use in hours per day. Children’s total screen media use was treated as a continuous measure after confirming that a linear dose-response relationship was appropriate. Parents also reported if they had rules for the amount of time their child could use screens (yes/no) and separately, rules for the content of media their child could access (yes/no). If rules were present, parents reported how often those rules were enforced (never, a little of the time, some of the time, most of the time). Responses for each set of questions were combined and dichotomized to define children with screen time rules that were enforced most of the time and, separately, those with media content rules enforced most of the time.

Parent screen media use.

Parents reported on their own, non-work related time spent engaging in nine screen media activities in the past 3 months: watching TV shows or movies, watching online videos or clips, using social media, engaging with apps, playing video games on the Internet (herein referred to as online gaming), reading e-books or magazines, emailing, text-messaging, and browsing websites. Parents reported on the time per day spent on each activity on a typical weekday and weekend day. Values were summed per day and a weighted average (5/7*weekday use+2/7*weekend day use) was created to reflect parent’s total daily screen media use in hours per day. We specifically analyzed parents’ time spent on screen activities that are particularly engaging and reinforcing to users: social media, apps, and online gaming. Parents’ total daily screen media use, social media use, and app use were categorized into tertiles to assess dose-response trends. Because most parents (80.7%) did not engage in online gaming, that measure was categorized into no online gaming, less than 1.9 hours per day or 1.9 or more hours per day, as 1.9 hours per day was the median daily time among parents who engaged in online gaming.

Covariates.

Parents reported their children’s age, gender, ethnicity, and race; their own age, education level, and relationship to the child; annual household income; homeownership status (own, rent or other); the total number of adults (≥18 years old) and the total number of children and adolescents (0–17 years old) who lived in the home. Parents also reported on household chaos as measured with the Confusion, Hubbub and Order Scale which includes 15 items to assess confusion, disorganization, and hurriedness in the home (Matheny et al., 1995). The final score is a sum of all responses (range 15–60) with a higher score indicating a home that is more chaotic. The chaos scale has been validated against direct observations of parental and household behaviors. Household chaos was included as a covariate to account for characteristics of the home environment that have been related to greater externalizing behaviors among children (Jaffee et al., 2012; Vernon-Feagans et al., 2016). Household chaos scores were categorized into tertiles to assess dose-response trends.

Statistical Analyses

Sample characteristics were described overall, and the prevalence of persistent requesting was compared across child, parent, and household characteristics using chi-square tests. The prevalence of each of the four requesting behaviors was compared between children with and without persistent requesting using chi-square tests; these comparisons were limited to children with any persistent requesting. Unadjusted Poisson regression with robust standard errors was used to compute the crude risk of persistent requesting by child and parent screen media use characteristics (Zou, 2004). Adjusted regression models were then used to assess the risk of persistent requesting on child and parent screen media use characteristics, adjusted for the types of screen devices and, separately, the types of screen media activities that children engaged in. Each model was adjusted for child age, gender, ethnicity and race, parent education, annual household income, and household chaos, all selected a priori. We also planned to include any other sociodemographic or household characteristics associated with persistent requesting at the p<0.10 from bivariate analyses. The threshold for statistical significance from the regression models was set to p<0.05. All analyses were completed using the R Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 3.6.1.

Results

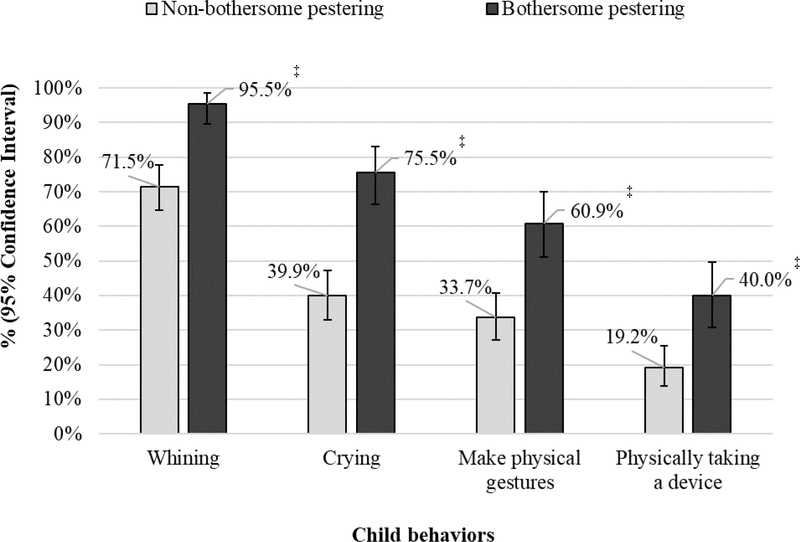

Among the 479 eligible parents enrolled, 385 completed the survey; analyses were limited to the 383 parents with children who used any screen media in the past 3 months. Each age group was well represented in the sample, genders were equally represented, and the sample was socio-demographically and economically diverse (Table 1). Most (94.8%) parents were mothers. On average, parents reported that their children spent 3.7 (SD=3.0) hours per day with screen media, most of which was spent watching TV programs or movies (M=2.1, SD=1.7 hours per day). Children averaged 0.7 (SD=1.0), 0.8 (SD=1.3), and 0.8 (SD=0.1) hours per day using apps, viewing online videos, or playing Internet video games, respectively. Overall, reports indicated that 110 children (28.7%) engaged in persistent requesting to use screen media. The prevalence of persistent requesting differed by age (p<0.001) and was highest among 3-year-olds (39.8%). Persistent requesting was lower among Hispanic versus non-Hispanic children (p=0.04) and increased with greater household chaos (p=0.01). No other child, parent, or household characteristic was associated with persistent requesting. Nearly all (95.5%) children that engaged in persistent requesting were reported to demonstrate whining; crying, making physical gestures, and physically taking a device were also common behaviors (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and associations with persistent requesting to use screen media.

| Overall | Outcome:

Persistent requesting |

P-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Column n (%) | n (%) with outcome | ||

|

| |||

| Overall | 383 (100%) | 110 (28.7%) | -- |

| Child characteristics | |||

| Age, years | |||

| 2 | 114 (29.8%) | 16 (14.0%) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 103 (26.9%) | 41 (39.8%) | |

| 4 | 95 (24.8%) | 32 (33.7%) | |

| 5 | 71 (18.5%) | 21 (29.6%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 186 (48.6%) | 55 (29.6%) | 0.81 |

| Male | 197 (51.4%) | 55 (27.9%) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 351 (91.6%) | 106 (30.2%) | 0.04 |

| Hispanic | 32 (8.4%) | 4 (12.5%) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 298 (77.8%) | 87 (29.2%) | 0.31 |

| Black | 30 (7.8%) | 7 (23.3%) | |

| Asian | 12 (3.1%) | 6 (50.0%) | |

| Other | 43 (11.2%) | 10 (23.3%) | |

| Parent characteristics | |||

| Age, years | |||

| 18–29 | 138 (36%) | 35 (25.4%) | 0.54 |

| 30–39 | 228 (59.5%) | 70 (30.7%) | |

| 40–49 | 17 (4.4%) | 5 (29.4%) | |

| Education level | |||

| High school or less | 136 (35.5%) | 34 (25.0%) | 0.30 |

| Associates degree | 53 (13.8%) | 13 (24.5%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 117 (30.5%) | 35 (29.9%) | |

| Graduate or professional school | 77 (20.1%) | 28 (36.4%) | |

| Household characteristics | |||

| Annual household income | |||

| Less than $25,000 | 49 (12.8%) | 9 (18.4%) | 0.34 |

| $25,000-$64,999 | 158 (41.3%) | 47 (29.8%) | |

| $65,000-$144,999 | 134 (35.0%) | 40 (29.9%) | |

| $145,000 or more | 17 (4.4%) | 4 (23.5%) | |

| I don’t want to answer | 25 (6.5%) | 10 (40.0%) | |

| Home ownership status | |||

| Own | 213 (55.6%) | 63 (29.6%) | 0.60 |

| Rent | 145 (37.9%) | 42 (29.0%) | |

| Other | 25 (6.5%) | 5 (20.0%) | |

| Overall | 383 (100%) | 110 (28.7%) | -- |

| Total adults (≥18 years old) in the home | |||

| 1 | 21 (5.5%) | 4 (19.1%) | 0.59 |

| 2 | 262 (68.4%) | 76 (29.0%) | |

| 3 or more | 100 (26.1%) | 30 (30.0%) | |

| Total children (0–17 years old) in the home | |||

| 1 | 72 (18.8%) | 19 (26.4%) | 0.71 |

| 2 | 163 (42.6%) | 45 (27.6%) | |

| 3 or more | 148 (38.6%) | 46 (31.1%) | |

| Household chaos2 | |||

| Least chaotic | 138 (36.0%) | 29 (21.0%) | 0.01 |

| Mid chaotic | 120 (31.3%) | 34 (28.3%) | |

| Most chaotic | 125 (32.6%) | 47 (37.6%) | |

Among 383 parents of preschool-age children who used any screen media in the past three months; parents were recruited nationally via social media for an online survey.

Persistent requesting includes “bothersome” or “very bothersome” requesting to use media devices versus no requesting or requesting that is “not bothersome at all” or “a little bothersome.”

P-values are from chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests when the sample size in any cell of the cross-tabulation was 5 or less.

Cut-points based on tertiles.

Figure 1:

Behaviors of Children Engaged in Persistent Requesting to use Media

‡P<0.001 based on chi-square tests.

There was a small, positive association between children’s total screen media use and risk of persistent requesting (Table 2); the risk of requesting increased 5% with each additional hour of children’s screen media use per day (prevalence risk ratio, PRR: 1.05; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.10). When considering children’s engagement with specific screen media devices or activities, using smartphones, using video game devices, and watching online videos were related to an increased risk of persistent requesting. The presence of enforced rules on screen media use was protective against persistent requesting, while the presence of enforced rules on the content of screen media activities was unrelated.

Table 2.

Distributions of children’s screen use characteristics and unadjusted associations with the child’s persistent requesting to use screen media.

| Overall (n=383) | Outcome: Persistent requesting (n=110) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | PRR (95% CI) | ||

|

| |||

| Child’s total screen use, hours per day, mean (SD)1 | 3.7 (3.0) | 383 | 1.05 (1.00, 1.10)* |

| Screen devices used by the child, n (%) | |||

| Traditional TV | 338 (88.3%) | 96 | 0.91 (0.57, 1.46) |

| Smartphone | 213 (55.6%) | 74 | 1.64 (1.16, 2.31)† |

| Touchscreen tablet | 202 (52.7%) | 64 | 1.25 (0.90, 1.72) |

| Kid’s touchscreen tablet | 112 (29.2%) | 32 | 0.99 (0.70, 1.41) |

| Desktop, laptop computer or "netbook" | 75 (19.6%) | 22 | 1.03 (0.69, 1.52) |

| Video game console or handheld device | 72 (18.8%) | 28 | 1.47 (1.05, 2.08)* |

| Screen activities the child engages with, n (%) | |||

| Watching TV programs or movies | 322 (84.1%) | 94 | 1.11 (0.71, 1.75) |

| Playing apps | 253 (66.1%) | 78 | 1.25 (0.88, 1.78) |

| Watching online videos or clips | 236 (61.6%) | 85 | 2.12 (1.43, 3.15)‡ |

| Playing Internet video games | 38 (9.9%) | 14 | 1.32 (0.84, 2.08) |

| Rules for child’s screen time | |||

| No rules, or not consistently enforced | 174 (45.4%) | 59 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Rules that are enforced most of the time | 209 (54.6%) | 51 | 0.72 (0.52, 0.99)* |

| Rules for the content of media child exposed to | |||

| No rules, or not consistently enforced | 48 (12.5%) | 14 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Rules that are enforced most of the time | 335 (87.5%) | 96 | 0.98 (0.61, 1.58) |

P<0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001

PRR: Prevalence risk ratio.

Among 383 parents of preschool-age children who used any screen media in the past three months; parents were recruited nationally via social media for an online survey.

Children’s total screen use is the sum of watching TV programs or movies, playing apps, watching online videos or clips and playing Internet video games.

When considering parent screen media use characteristics (Table 3), the risk of persistent requesting appeared greater when parents averaged higher daily screen media use, yet those associations were not statistically significant. Greater daily social media use by parents was strongly and statistically associated with persistent requesting, while parent’s daily app use and online gaming were unrelated.

Table 3.

Distributions of parent’s screen use characteristics and unadjusted associations with the child’s persistent requesting to use screen media.

| Overall (n=383) | Outcome: Persistent requesting (n=110) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n | PRR (95% CI) | |

|

| |||

| Parent’s daily screen use1 | |||

| 6.7 or less hours per day | 127 (33.2%) | 29 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 6.7 to 11.7 hours per day | 127 (33.2%) | 40 | 1.38 (0.92, 2.08) |

| 11.7 or more hours per day | 129 (33.7%) | 41 | 1.39 (0.93, 2.09) |

| Parent’s daily social media use1 | |||

| 1.3 or less hours per day | 130 (33.9%) | 25 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1.3 to 3.0 hours per day | 128 (33.4%) | 42 | 1.71 (1.11, 2.62)* |

| 3.0 or more hours per day | 125 (32.6%) | 43 | 1.79 (1.17, 2.74)† |

| Parent’s daily app use1 | |||

| 0.4 or less hours per day | 126 (32.9%) | 35 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 0.4 to 2.0 hours per day | 132 (34.5%) | 39 | 1.06 (0.72, 1.56) |

| 2.0 or more hours per day | 125 (32.6%) | 36 | 1.04 (0.70, 1.54) |

| Parent’s daily online gaming1 | |||

| None | 309 (80.7%) | 87 | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1.9 or less per day | 43 (11.2%) | 16 | 1.32 (0.86, 2.03) |

| 1.9 or more per day | 31 (8.1%) | 7 | 0.80 (0.41, 1.58) |

P<0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001

PRR: Prevalence risk ratio. SD: Standard deviation.

Among 383 parents of preschool-age children who used any screen media in the past three months; parents were recruited nationally via social media for an online survey.

Cut-points based on tertiles.

In the adjusted regression analyses (Table 4), there were no associations between persistent requesting and children’s total daily screen media use, presence of enforced rules on children’s screen time, or enforced rules on content access. Children’s use of a smartphone (Model 1; PRR: 1.57; 95% CI: 1.11, 2.22) and, separately, engagement with online videos (Model 2; RR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.40, 3.00) were each associated with persistent requesting. Greater daily use of social media by parents also remained positively associated with children’s persistent requesting while parents’ daily use of all other screen media was unassociated. Parents’ daily use of apps or online gaming was not associated with persistent requesting in univariate or in adjusted analyses, and thus those measures were not included as predictors in the final models. In each final model (Table 4), greater household chaos was positively associated with persistent requesting.

Table 4.

Adjusted associations between parent and child screen use characteristics with the child’s persistent requesting to use screen media.

| Outcome: Persistent requesting (n=110) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 Adjusted for child’s screen device use | Model 2 Adjusted for child’s screen activity use | |

| PRR (95% CI) | PRR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||

| Child screen media characteristics | ||

| Child’s total screen use, hours per day1 | 1.03 (0.96, 1.09) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) |

| Screen devices the child uses | ||

| Traditional TV | 0.74 (0.48, 1.16) | -- |

| Smartphone | 1.57 (1.11, 2.22)* | -- |

| Touchscreen tablet | 0.93 (0.66, 1.30) | -- |

| Kid’s-specific touchscreen tablet2 | 0.95 (0.67, 1.35) | -- |

| Desktop, laptop computer or "netbook" | 0.85 (0.59, 1.24) | -- |

| Video game console or hand-held device | 1.20 (0.84, 1.71) | -- |

| Screen activities the child engages with | ||

| Watch TV programs or movies | -- | 1.20 (0.78, 1.84) |

| Play or engaged with “apps” | -- | 1.03 (0.71, 1.50) |

| Watch online videos or clips | -- | 2.05 (1.40, 3.00)‡ |

| Play video games on the Internet | -- | 0.97 (0.60, 1.58) |

| Rules for child’s screen time | ||

| No rules, or not consistently enforced | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Rules that are enforced most of the time | 0.84 (0.60, 1.18) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.2) |

| Rules for child’s screen content accessed | ||

| No rules, or not consistently enforced | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Rules that are enforced most of the time | 0.97 (0.61, 1.55) | 1.00 (0.63, 1.60) |

| Parent screen media characteristics | ||

| Parent’s daily screen use excluding social media | ||

| 4.8 or less hours per day | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 4.8 to 9 hours per day | 0.82 (0.56, 1.2) | 0.81 (0.55, 1.19) |

| 9 or more hours per day | 0.91 (0.58, 1.42) | 0.96 (0.62, 1.47) |

| Parent’s daily social media use | ||

| 1.3 or less hours per day | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 1.3 to 3.0 hours per day | 1.56 (1.00, 2.44)* | 1.57 (0.99, 2.48) |

| 3.0 or more hours per day | 2.03 (1.24, 3.33)† | 2.08 (1.26, 3.43) † |

| Household chaos 1 | ||

| Least chaotic | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Mid chaotic | 1.12 (0.73, 1.71) | 1.13 (0.74, 1.74) |

| Most chaotic | 1.43 (0.95, 2.13) | 1.54 (1.05, 2.27)* |

P<0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001

PRR: Prevalence risk ratio.

Among 383 parents of preschool-age children who used any screen media in the past three months; parents were recruited nationally via social media for an online survey. Persistent requesting includes “bothersome” or “very bothersome” requesting to use media devices versus no requesting or requesting that is “not bothersome at all” or “a little bothersome.” Each model was also adjusted for child age, gender, ethnicity and race; parent education and annual household income.

Children’s total screen use is the sum of watching TV programs or movies, playing apps, watching online videos or clips and playing Internet video games.

We conducted an additional exploratory analysis to examine the dose-response relationship between children’s watching of online videos and persistent requesting. Visualization of the associations supported a threshold effect where the risk increased up to 0.5 hours per day and then plateaued. There were no dose-response relationships evident when examining trends for the associations between children’s daily time spent on the other screen media activities and requesting.

Discussion

In this socio-economically diverse, nationally recruited sample, parents reported that more than 1 in 4 preschool-age children engaged in persistent requests to use screen media, which we defined as persistent requesting. Behaviors associated with persistent requesting included whining, crying, and physical gestures. Children’s total daily screen media use was unrelated to persistent requesting in our sample, and persistent requesting appeared equally common across the various screen media devices and activities. We found that only two aspects of children’s screen media use were related to persistent requesting: the use of smartphones and engagement with online videos. The strongest and most consistent predictor of children’s persistent requesting was the amount of time parents spent using social media, an effect that was independent of parents’ total screen time and household chaos. Findings highlight the need to consider both child and parent screen media use habits when identifying sources of conflict related to children’s screen media use.

Our results align with prior research documenting parents’ self-reported concerns with tensions around managing children’s screen media use (Hiniker et al., 2016). We found limited evidence that children’s total screen media use and other characteristics of children’s use were uniquely associated with persistent requesting to use screen media, indicating that such conflicts are equally frequent across all screen devices and activities. However, persistent requesting was more prevalent when children used smartphones or when they viewed online videos. Mobile devices differ greatly from other devices in their portability, ease of use, and access to varied and engaging content. Caregivers also commonly provide mobile devices to their young children to occupy or pacify them in multiple environments, including when out in public (Hiniker et al., 2016; Kabali et al., 2015; Radesky et al., 2016; Wartella et al., 2014). Online videos, including those accessed via YouTube, are designed to be enticing and engaging for young children, and provide outlets for entertainment, pass-time, and content-seeking that produce strong user gratification (Balakrishnan & Griffiths, 2017; Burroughs, 2017). Thus, it is possible that managing young children’s online video use also offers unique challenges for parents.

The findings of a positive association between parents’ report of their own social media use and persistent requesting to use screens among young children warrants further examination. It is possible that parent social media use has a direct effect on children’s requesting behavior if, as suggested by previous studies, parents are less attentive to their children when engaged in social media and as a result, children may exhibit more externalizing behaviors (Radesky et al., 2014, 2015). Greater social media use could also be a proxy for general disengagement or greater internalizing behaviors of the parent that could adversely impact parenting (Shakya & Christakis, 2017).

Established routines around young children’s screen media use likely reduce conflict related to that use (Beyens & Beullens, 2017; Hiniker et al., 2016). In our study, the presence of enforced rules determining the time children spent with screen media was protective against persistent requesting in unadjusted analyses. However, that finding was attenuated in adjusted analyses, suggesting that the protective effect might be confounded by other factors. Additionally, we did not capture the type of screen media use rules (e.g., general rules on total screen media use per day versus more specific rules for a specified timeframe of use) or the methods used to transition children away from screens when the time limit was reached, all of which can impact the conflict over children’s transition away from screen media use (Hiniker et al., 2016).

While these results come from a nationally recruited sample, this study does have the limitation of only including parent report (i.e., no observational data were collected). Studies have shown that individuals are only moderately accurate at reporting their own media use, and parents are not completely objective in rating the frequency of their children’s behaviors (Boase & Ling, 2013; Wood et al., 2019). However, by using survey methods, we were able to obtain data from a large sample of parents across the United States. We recommend that future research investigates these associations using observational methods to address this limitation.

Conclusion

The findings from this study indicate the importance of assessing family screen media use habits when determining sources of conflict in the home. Clinicians and other service providers should particularly take notice of children’s use of smartphones and viewing of online videos, as these may be associated with persistent requesting for screen media. It is important to consider both child and parent screen media use habits, as the social media use of parents may also be an important factor in persistent requesting. Future research should seek to replicate these findings with observational measures of parent-child interactions. Assessing children’s behaviors after devices or screens are removed, in a home or laboratory setting, may elicit additional indicators of parent-child conflict around screen media use that could be addressed clinically.

Funding statement:

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number 1K01DK117971 to Dr. Emond).

Conflict of interest disclosure: Dr. Domoff is on the Board of the SmartGen Society, and regularly receives honoraria for speaking invitations to different academic and non-profit institutions. Dr. Domoff has received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Children’s Foundation (Michigan).

Biography

Sarah E. Domoff, PhD

Sarah E. Domoff, Ph.D., is a licensed psychologist and Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology at Central Michigan University (CMU) and Research Faculty Affiliate at the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan. She established the Problematic Media Assessment and Treatment Clinic at the Center for Children, Families and Communities at CMU, where she trains clinicians to provide evidence-based care to children and adolescents who experience conflict and stressors related to digital media use. Additionally, at her clinic, Dr. Domoff trains school personnel and other providers in promoting healthy digital media use among children and adolescents.

Twitter: @sarah_domoff

Website: www.sarahdomoff.com

Aubrey L. Borgen, MA

Aubrey L. Borgen, MA, is a doctoral student in the Clinical Psychology program at Central Michigan University. Ms. Borgen is a research assistant in Dr. Sarah Domoff’s Family Health Lab, where she is currently assisting with projects investigating the impact of parenting on obesogenic behaviors in childhood. Her research interests include identifying strategies for managing the screen use of young children and helping adolescents develop healthy social media use. Ms. Borgen’s clinical interests include assessing for problematic media use and coaching parents in improving child health behaviors.

Sunny Jung Kim, Ph.D.

Sunny Jung Kim (Ph.D., Cornell University) is Assistant Professor in the Department of Health Behavior and Policy at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) School of Medicine, and a Co-Director of the Health Communication and Digital Innovation (HCDI) Core at VCU Massey Cancer Center. Dr. Kim is a health communication and media scholar by training, specializing in theory-based persuasive technologies for health research and their effects on social, psychological mechanisms of behavior change. Her research focuses on translating Communication and Social Psychology principles, leveraging communication technologies, and implementing mixed methods in new media environment to understand health/social phenomena and disseminate effective interventions and campaign messages to promote social and behavioral medicines for underserved at-risk populations.

Jennifer A. Emond, Ph.D.

Jennifer A. Emond is Assistant Professor of Biomedical Data Sciences at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College. Her research focuses on modifiable risk factors for obesity among young children and adolescents, with a particular emphasis on how screen media use impacts diet and food-cue responsiveness, physical activity and sleep.

Footnotes

Ethics approval statement: The study was approved by the Dartmouth College Institutional Review Board.

Patient consent statement: All participants provided electronic consent to participate in the study.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources: No material was reproduced from other sources.

Data availability statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2016, October 21). American Academy of Pediatrics announces new recommendations for children’s media use. HealthyChildren.org. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/news/Pages/AAP-Announces-New-Recommendations-for-Childrens-Media-Use.aspx

- Balakrishnan J, & Griffiths MD (2017). Social media addiction: What is the role of content in YouTube? Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6, 364–377. 10.1556/2006.6.2017.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyens I, & Beullens K (2017). Parent–child conflict about children’s tablet use: The role of parental mediation. New Media & Society, 19, 2075–2093. 10.1177/1461444816655099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boase J, & Ling R (2013). Measuring mobile phone use: Self-report versus log data. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18, 508–519. 10.1111/jcc4.12021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs B (2017). YouTube kids: The app economy and mobile parenting. Social media + Society, 3, 1–8. 10.1177/2056305117707189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domoff SE, Radesky JS, Harrison K, Riley H, Lumeng JC, & Miller AL (2019). A naturalistic study of child and family screen media and mobile device use. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 401–410. 10.1007/s10826-018-1275-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M, Lenhart A, Lampe C, Ellison NB (2015). Parents and social media. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2015/07/Parents-and-Social-Media-FIN-DRAFT-071515.pdf

- Emond JA, Tantum LK, Gilbert-Diamond D, Kim SJ, Lansigan RK, & Neelon SB (2018). Household chaos and screen media use among preschool-aged children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 18, 1–8. 10.1186/s12889-018-6113-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiniker A, Suh H, Cao S, & Kientz JA (2016). Screen time tantrums: How families manage screen media experiences for toddlers and preschoolers. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 648–660). Association for Computing Machinery. 10.1145/2858036.2858278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Hanscombe KB, Haworth CM, Davis OS, & Plomin R (2012). Chaotic homes and children’s disruptive behavior: A longitudinal cross-lagged twin study. Psychological Science, 23, 643–650. 10.1177/0956797611431693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabali HK, Irigoyen MM, Nunez-Davis R, Budacki JG, Mohanty SH, Leister KP, & Bonner RL (2015). Exposure and use of mobile media devices by young children. Pediatrics, 136, 1044–1050. 10.1542/peds.2015-2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny AP Jr, Wachs TD, Ludwig JL, & Phillips K (1995). Bringing order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16, 429–444. 10.1016/0193-3973(95)90028-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radesky JS, Kistin CJ, Zuckerman B, Nitzberg K, Gross J, Kaplan-Sanoff M, Augustyn M, & Silverstein M (2014). Patterns of mobile device use by caregivers and children during meals in fast food restaurants. Pediatrics, 133, e843–e849. 10.1542/peds.2013-3703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radesky J, Miller AL, Rosenblum KL, Appugliese D, Kaciroti N, & Lumeng JC (2015). Maternal mobile device use during a structured parent–child interaction task. Academic Pediatrics, 15, 238–244. 10.1016/j.acap.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radesky JS, Peacock-Chambers E, Zuckerman B, & Silverstein M (2016). Use of mobile technology to calm upset children: Associations with social-emotional development. JAMA Pediatrics, 170, 397–399. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen EE, Shafer A, Colwell MJ, White S, Punyanunt-Carter N, Densley RL, & Wright H (2016). Relation between active mediation, exposure to Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, and US preschoolers’ social and emotional development. Journal of Children and Media, 10, 443–461. DOI: 10.1080/17482798.2016.1203806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V (2017). The Common Sense census: Media use by kids age zero to eight. Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/csm_zerotoeight_fullreport_release_2.pdf

- Rideout VJ, Foehr UG, & Roberts DF (2010). Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8-to 18-year-olds. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/8010.pdf

- Schneider‐Rosen K, & Wenz‐Gross M (1990). Patterns of compliance from eighteen to thirty months of age. Child Development, 61, 104–112. 10.2307/1131051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya HB, & Christakis NA (2017). Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 185, 203–211. 10.1093/aje/kww189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiglic N, & Viner RM (2019). Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open, 9, e023191. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon-Feagans L, Willoughby M, Garrett-Peters P, & Family Life Project Key Investigators (2016). Predictors of behavioral regulation in kindergarten: Household chaos, parenting, and early executive functions. Developmental Psychology, 52, 430–441. 10.1037/dev0000087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartella E, Rideout V, Lauricella AR, & Connell S (2014). Revised parenting in the age of digital technology: A national survey. Center on Media and Human Development, School of Communication, Northwestern University. https://cmhd.northwestern.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ParentingAgeDigitalTechnology.REVISED.FINAL_.2014.pdf

- Whitaker C, Stevelink S, & Fear N (2017). The use of Facebook in recruiting participants for health research purposes: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19, e290. 10.2196/jmir.7071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood CT, Skinner AC, Brown JD, Brown CL, Howard JB, Steiner MJ, … & Perrin EM (2019). Concordance of child and parent reports of children’s screen media use. Academic Pediatrics, 19, 529–533. 10.1016/j.acap.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G (2004). A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159, 702–706. 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.