BACKGROUND

Home-based health care refers to primary, urgent, or palliative care for “high-risk, medically vulnerable patients” in the comfort of their homes (American Academy of Home Care Medicine, n.d.). Approximately 2 million older adults in the U.S. are homebound and have difficulty obtaining office-based primary care due to functional limitations, frailty, or multiple chronic conditions (Ankuda et al., 2021). Female, non-White, and people with less education and income are disproportionately affected (Ankuda et al., 2021; De Jonge et al., 2014). Homebound older adults are the most expensive patients, accounting for about half of the costliest 5% Medicare beneficiaries (De Jonge et al., 2014; Stanhope et al., 2018). With a rapidly aging population, homebound older adults are expected to increase (Ankuda et al., 2021; Ong et al., 2018). It is important to develop and implement effective home-based interventions to help address medical and non-medical needs (Norman et al., 2018) of the homebound.

Home-based health care, when healthcare professionals visit patients’ home to diagnose or to provide treatment, has been commonly referred to “home visits” or “house calls” (U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d.). This service may be provided virtually. For example, a virtual medication reconciliation program was successfully implemented for home-based primary care patients (Monzón-Kenneke et al., 2021). Similarly, home-based primary care practices in New York City delivered virtual mental health services combined with necessary in-person contact to home-based medically complex patients experiencing depression (Franzosa et al., 2021). Home-based care has had an overall positive effect on patient outcomes, with reduction in the number and length of hospital visits (Gonzalez-Jaramillo et al., 2020) and delays in long-term institutionalization (Valluru et al., 2019). Participants of this care model have also experienced substantial cost savings. For example, in a matched cohort study, Stanhope et al. (2018) found an estimated $37,037 in savings over 24 months among home-based primary care participants relative to matched controls.

Nurses, physical and occupational therapists, and physicians have traditionally been the most common providers of home health care (Crowley et al., 2016). Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (referred to as NPs hereafter) have also provided home-based primary care services that are within the scope of their practice such as comprehensive head-to-toe assessment, diagnosis, prescribing or adjusting medication and treatment. Nevertheless, NPs had significant regulatory restraints which required physicians to sign home health certifications, even if NPs were primary care providers for their patients (American Association of Nurse Practitioners, n.d.). Then in 2020, the U.S. Senate passed the Home Health Care Planning Improvement Act (S. 296/H.R. 2150) as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the “CARES Act” (H.R. 748), which includes permanent authorization of NPs to order home health care services for Medicare patients (American Nurses Association, 2020).

NP home visits have increased nearly two-fold in just over three years (1.1 million visits in 2013 to 2+ million in 2016) (Wolff-Baker & Ordona, 2019; Yao et al., 2017). Despite the growing popularity, there is limited information about the scope and nature of NP home-based interventions and outcomes. We found three reviews addressing relevant topics. Osakwe et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review of seven studies addressing the impact of NP home visits. The authors found that a relationship between NP home visits and patient outcomes was limited, with one study each investigating the quality of life and functional status of homebound older adults. The nature and scope of NP home visits were not clearly described in the review, however. In an integrative review, Mora et al. (2017) reported that NP interviews (though not exclusively led by NPs) resulted in reduced hospital readmission rates. However, the review addressed NP interventions exclusively within the context of transitional care. Finally, a recent systematic review (Zimbroff et al., 2021) included 79 studies examining home-based primary care and revealed positive outcomes, but the interventionists included diverse practice groups (e.g., pharmacists, physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers, case managers, NPs).

OBJECTIVES

Given the increasing need for home-based health care and the essential roles NPs play in home health care, it is important to understand the scope and nature of NP home visit interventions and associated outcomes. NP interventions in transitional care have been studied extensively and included in two of the aforementioned reviews (Mora et al., 2017; Osakwe et al., 2020). Hence, the purpose of this systematic review is to synthesize the research evidence of NP visits in home-based “primary” care. For our purposes, we defined primary care as the provision of continuous, comprehensive, non-specialized care in the context of community and family.

METHODS

SEARCH STRATEGIES

We prepared this review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). A systematic search for peer-reviewed literature was conducted initially in December 2020 and an updated search in January 2021 in six databases—PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, Cochrane, Web of Science, and Scopus. These databases were searched from their inception to identify relevant studies published in English.

Following consultation with a health sciences librarian, peer-reviewed articles were searched with Boolean operators. Search terms included: “nurse practitioners” OR “nurse practitioner”; “house calls” OR “home visit” OR “home care” OR “primary health care”; and “Primary Care Nursing” OR “Primary care” OR “primary health care” OR “Primary healthcare.” We also searched for the term nurse within three words of practitioner (nurse NEAR/3 practitioner); primary within three words of care or healthcare (primary NEAR/3 (care OR ‘healthcare)); and home or house within three words of care or visit ((home W/3 visit) OR (house W/3 call). Detailed search terms for each database are provided in Appendix 1.

ELIGIBILITY—INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA

We included studies if they met each of the following conditions: interventions were led at least in part by NPs; performed within a U.S. home-based primary care setting, had measured outcomes, and could be classified as human subjects research. With respect to home-based care, we also included studies that leveraged telehealth as a mechanism for intervention delivery. Studies were excluded if the intervention focused on transitional or palliative care, if the interventionists were primarily midwives, or if they were based on quality improvement projects. We did not exclude studies based on their published dates in order to provide a more comprehensive summary of home-based primary care intervention made by NPs.

STUDY SELECTION

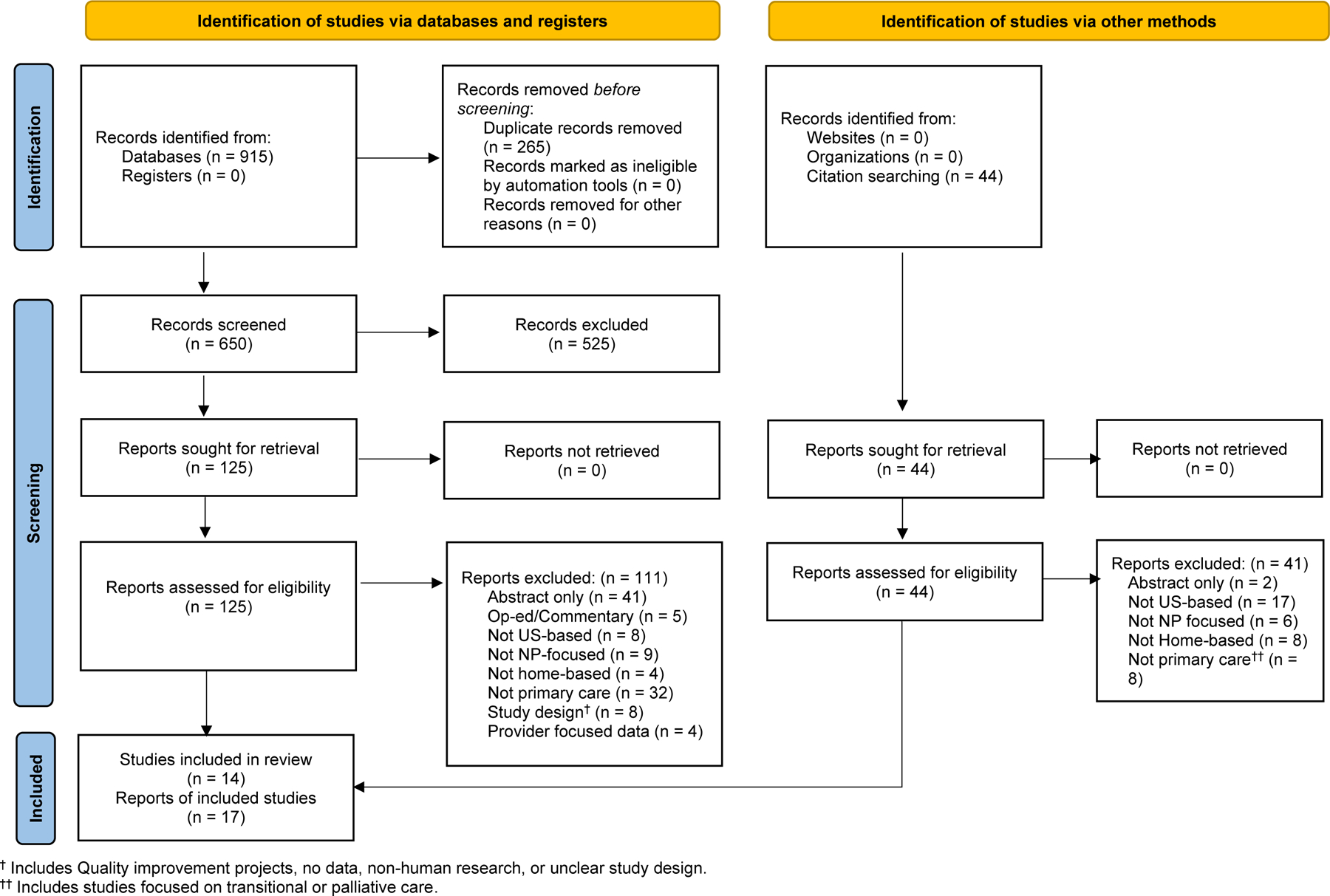

The electronic search resulted in 915 references, which were imported into a systematic review management tool—Covidence (Moher et al., 2009)—for screening. A total of 265 duplicates were removed, resulting in 650 articles forwarded to the title and abstract screening stage. Three review authors (CAS, CP, JG) screened the titles and abstracts independently for inclusion eligibility; disagreements were resolved through consensus. A total of 525 records were excluded based on the established criteria. An additional 44 articles were identified through a hand search of references included in relevant articles, leaving 169 articles for full-text review. After full-text screening, consensus was reached through similar means. Four review authors convened to resolve disagreements (HRH, CAS, CP, JG), and 111 records from the databases and 41 records from the hand search were excluded for the reasons identified in Figure 1, yielding 17 articles to include in the review.

Fig 1. PRISMA diagram of a review of NP-led home-based primary care interventions.

Describes number of studies identified, screened, and included

QUALITY ASSESSMENT

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality assessment tool—developed to aid in clinical decision-making in healthcare—is an evidence-based critical appraisal instrument that assesses the methodological rigor of studies included in a systematic review (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017). We used the corresponding JBI tool for each of the 3 types of study designs employed in the articles included in the review (randomized controlled trials [RCTs], quasi-experimental, and qualitative). No studies were excluded based on quality assessment, which was conducted independently by two pairs of two raters. Each pair reviewed one half of the total studies included for full-text review. Studies were rated as having high, medium, or low quality by meeting assessment components (total score >66.6%, 33.4% to 66.6%, or <33.4%, respectively). Inter-rater agreement rates ranged from 84.6% to 100%, with the resulting statistics indicating substantial agreement (average inter-rater agreement rate = 95.9%). All scoring discrepancies were resolved via inter-rater discussion.

RESULTS

OVERVIEW OF STUDIES

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the 14 unique studies reported in 17 articles. Two companion articles provided preliminary results (Counsell et al., 2006) and cost analysis (Counsell et al., 2009) of the study testing a geriatric home care management program (Counsell et al., 2007). Another companion article (Jones, Ornstein et al., 2017) described sample characteristics and reasons for referral to NP co-management of homebound patients (Jones, DeCherrie et al., 2017). For the studies with companion articles, we extracted relevant information from all relevant articles but reported only the final results. Four of the 14 unique studies were RCTs (Counsell et al., 2007; Stone et al., 2010; Stuck et al., 1995; Zimmer et al., 1985); eight were quasi-experimental (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Palfrey et al., 2004; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010); the remaining two were qualitative studies (Dick & Frazier, 2006; Muramatsu et al., 2004).

Table 1.

Study Characteristics and Results

Overview of all included studies, including author name, design/timeline, quality rating, population focus, sample demographics, NP role in home-based intervention/visit schedule, and main findings

| First author, Year | Design/Timeline | Quality Rating | Population age/focus | Sample demographics | NPs’ role in home-based Intervention/Visits schedule | Main Outcome [measurement] | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bryant, 2014 | Quasi-experiment pre-post/6 months | High | Older adults (65+)/ Homebound with heart failure |

N=18 Mean age: not reported Female: 72.2% Education ≥ high school graduate 50.0% Race/ethnicity: not reported |

One-on-one counseling education, disease management (treatment, evaluation), medication reconciliation, care coordination/ Three schedule visits (initial, 5 weeks, 10 weeks) |

Utilization- hospitalization [health record], Other- Self-care behavior [self-reported self-care of heart failure index] |

Hospitalization decreased compared to before intervention (0 vs 1.39 [SD1.539]) Self-care behavior increased (maintenance 5.7 (df:16), p < .001; management 4.9 (df:4), p < .01; confidence 6.9 (df:17), p < .001.) |

| Coppa, 2018 | Quasi-experiment pre-post | High | Adults/ 7-day within post hospitalization and/or who met high risk high utilizer criteria by CMS living in the catchment area |

N=95 Mean age: 60.6 Female: 73% Education: not reported Race/ethnicity: White 86% |

NP history taking, vital signs, physical examination, medication reconciliation, primary care plan, and care coordination/ As needed |

Utilization- hospitalization, ED admission, urgent care use [insurance claims, health records] |

Pre-post comparison: Fewer ED visit (1.24 (SD 0.30) vs 0.55 (SD0.11), p <.001). Hospitalization (0.58 (SD0.12) vs 0.35 (SD.0.07), p >.05) urgent care visit (0.03 (SD0.63) vs 0.04 (SD0.02) p >.05) |

| Counsell, 2006, 2007, 2008 | Randomized controlled trial | High | Older adults (65+)/ with annual income <200% of the federal poverty level |

N=951 Intervention group (n=474) Mean age: 71.8 Female: 75.5% Education >high school graduate 37.5% Race/ethnicity: Black 57.6% Control (n=477) Mean age: 71.6 Female: 76.5% Education >high school graduate 40% Race/ethnicity: Black 62.4% |

NP implement the care plan and coordinate care between providers and patients, family members or caregivers via face-to-face visits and telephone contacts/ 1 initial in-home visit to review the care plan, at least 1 telephone or face-to-face contact month, a face-to-face home visit after ED visit or hospitalization, and as needed |

Utilization- hospitalization, ED admission, [regional health information exchange] Health status- activities of daily living (ADLs), Quality of Life (QOL) [AHEAD, SF36 questionnaire] |

The cumulative 2-year ED visit rate per 1000 patients was lower in the intervention group (1445 vs 1748, p <.05). The cumulative 2-year hospitalization rates per 1000 did not differ between group (700 vs 740, p >.05). 2-year mean changes of instrumental ADL and basic ADL did not differ between group (0.4 (3.3)/0.2 (2.7) vs 0.6 (3.6)/0.4 (2.7), p >.05). 2-year mean changes of SF-36 scales physical health did not differ between group (−1.1 (8.9) vs −1.6 (8.8), p >.05). The intervention group had better 2-year improvement for SF-36 mental health (2.1 (10.2) vs -0.3 (10.8), p <.001) |

| Dick, 2006 † | Qualitative | High | Older adults (65+)/ frail homebound |

N=36 Mean age: 48.2 Female 100% Education master 100% Race/ethnicity: White 97.2% |

NPs manage health issues, care coordination, teaching-coaching function/ As needed |

Utilization- hospitalization, ED visits [Qualitative interview] Health status- fall, death [qualitative interview] Other- medication error [qualitative interview] |

The NPs believed they prevented medication errors, falls, ED visits, hospitalizations, deaths. |

| Hahn, 2005 | Quasi-experiment pre-post | Medium | Adults/ Community-living adults with intellectual and developmental disability who in a 25-mile radius of the study site |

N=70 Mean age: 41.3 (20–65) Female: 51.4% Education: ≥high school graduate 63.5% Race/ethnicity: White 75.7%, Black 10%, Latino 14.3% |

NP completed comprehensive geriatric assessment (medical history, physical exam, hearing screening, gait and balance, preventive care, nutrition risk, functional assessment of activities of daily living, depression, social support, mental status), examined prescribed and over-the-counter medications, home-safety assessment initially, contact and review active problems and recommendations via mail/ Initial, every 3 months for 2–3 times |

Health status- Health Risk Reduction [questionnaire] | Health risk reduction (pre vs post 4.7 vs 3.5, p <.05) |

| Jones 2017 | Quasi-experiment | High | Adults, 85% 70+/ Homebound patients who are high-risk high utilization (frequent hospitalization and ED visits, disease exacerbation) |

N=1,114 Intervention (n=87) Mean age: 72.31 Female: 70.1% Education: not reported Race/ethnicity: White 33.3% Control (n=1,027) Mean age: 80.30 Female: 76.8% Education: not reported Race/ethnicity: White 38.2% |

NP conducted post-discharge visits within 7–14 days, symptom management, medication management, quality of life improvement, care coordination and transition. Phone contact for acute problems/ At least monthly |

Utilization- hospitalization, 30-day readmission [questionnaire] | Less hospitalizations (pre vs post 1.38 vs 0.74, p <.001), lower readmission rate (pre vs post 0.38 vs 0.15, p <.05). |

| Kobb, 2003 | Quasi-experiment prospective two groups | High | Veteran adults/ Chronically ill with high-cost medical care needs ($25k) and high-use (2+ hospitalization, ED visits, unscheduled walk-in visits & 10+ prescription) in the past year |

N=1401 Intervention (n=451) Mean age: 72 Female: 2% Education: not reported Race/ethnicity: White 65% Controlled (n=1120) Mean age: 70 Female: 2% Education: not reported Race/ethnicity: White 70% |

NPs use home-telehealth devices to monitor and educate patients to prevent health crises / Weekly and quarterly contact, daily blood pressure monitor, as needed if significant changes |

Utilization- hospitalization, ED visit [medical records] Health status- functional health [SF 36 V questionnaire] |

Intervention group had less hospitalization compared to controlled group (−60 vs +27, p: not reported), ED visit (−66 vs +22, p not reported). Among 281in intervention group, improved perceived physical health between baseline and 12 months (28 vs 40, p: not reported). |

| Muramatsu 2004 | Qualitative | Medium | Adults/ Patients meet the Medicare definition of homebound |

N= unknown Interview (n=unknown) 3 focus groups (n=27) |

NP assess home environment, establish diagnoses, design comprehensive treatment plans, coordinate other services/ As needed |

Utilization- hospitalization, ED admission [Qualitative] Health status- perceived health status [Qualitative] Other- communication |

The program reduces use of hospital and emergency services. The program improved patients’ medication and health management and optimizes health. Caregivers more informed about the patients’ medical conditions. |

| Palfrey 2004 | Quasi-experiment Pre-post one group | High | Children/ with special health care needs, (had >3 hospitalization in the last year, dependent on a wheelchair, early intervention for developmental impairment, ongoing need for home- or school-based health care services) |

N=150 Mean age: 5.6 (SD4.5) Female 33.3% Mother’s Education: ≥ high school graduate 67.4% Race/ethnicity White 58.7% |

NP initial home visit to evaluate needs, sick visits, streamline medication and supplies ordering, coordinate appointment, consolidate children’s medical records/ Not mentioned |

Utilization- hospitalization, ED visits [questionnaire] Health status- Illness measure [questionnaire, missed work or school] |

Less hospitalization (pre vs post 57.7% vs 43.2%, p <.01). No difference in ED visits (pre vs post 53.1% vs 53.9%, p >.05). Parents missed less work (pre vs post 26.3% s 14.1%, p <.05); missed schools >20 days (pre vs post 10.4% vs 11.7%, p >.05). |

| Stone 2010 | Randomized controlled trial | High | Adults veterans/ diabetes with an A1C ≥ 7.5% |

N=137 Intervention (n=64) Age: ≥45yo 95.3% Female: 0% Education: ≥ high school graduate 89% Race/ethnicity White 71.9% Control (n=73) Age: ≥45yo 94.5% Female: 2.7% Education: ≥ high school graduate 89% Race/ethnicity White 80.8% |

Home telemonitoring device reviewed by NP via phone contact, medication adjustment, counseling/ Monthly |

Health status- A1C, blood pressure, weight, fasting lipid panel [medical records] | Greater decrease in A1C at 3 months (intervention vs control 1.7% vs. 0.7%, p <.001), 6 months (1.7% vs 0.8%, p <.001). |

| Stuck 1995 | Randomized controlled trial | High | Older adults (75+)/ living at home |

N=414 Intervention (n=215) Mean Age: 81 (SD3.9) Female: 69% Education: ≥ high school graduate 80% Race/ethnicity: not reported Control (n=199) Mean Age: 81.4 (SD4.2) Female: 71% Education: ≥ high school graduate 76% Race/ethnicity: not reported |

NP comprehensive geriatric assessment, including medical history taking, physical examination (lab, functional status, oral health, mental status, gait and balance, percentage of ideal body weight, vision, hearing, extensiveness of social network, quality of social support, safety in the home and ease of access to the external environment), medications review, make recommendations/ Annual comprehensive assessment, follow-up every 3 months, phone contact as needed |

Utilization- hospitalization, nursing home admission [Medicare claims] Health status- functional status [questionnaire] |

Acute Care admission (Intervention vs control 99 (46) vs 93 (47) aOR 1.0 (0.8–1.4) p <.05)*, Nursing home admission (Intervention vs control 9 (SD4) vs 20(SD10) aOR 0.4 (0.2–0.9) p <.05)* *aOR adjusted for age, sex, baseline self-perceived health, bassline functional status. Better basic ADL (intervention vs control (basic ADL intervention vs control 96.8 (94.8–98.8) vs 95.4 (93.4–97.4) p <.05), instrumental ADL (intervention vs control 92.3 (69.0–75.6) vs 69.3 (66.0–72.6), p <.05); basic and instrumental ADL (intervention vs control 75.6 (73.2–77.9) vs 72.7 (70.2–75.2) p <.05) |

| Swartz 2019 | Quasi-experiment | High | Children/ chronic asthma |

N=37 Mean age: 9.1 (range 6–16) Female: 43% Education: not reported Race/ethnicity: 48% Black, 35% White, 21% Hispanic |

NPs review symptom assessment, conduct physical assessment, review medication delivery, identify and mitigate asthma triggers, coordinate planning and information sharing with the specialty care team and primary care provider, provide intensive education/ Not mentioned |

Utilization- hospitalization, ED visits, ICU admission [medical records] Health status- the frequency of nighttime symptoms, number of missed school days, the number of intubations, the number of courses of oral steroid therapy, level of asthma severity, level of control [medical records] |

Fewer hospitalization (t test 4.399 df 26 p<.001), fewer ICU admissions (t test 3.077, df 25 p <.05), fewer primary care provider visits (t test 2.179 df 14 p <.05), no difference in ED visits (t test 1.638, df 25, p >.05) Improved pediatric outcome, including fewer nighttime symptoms (t test 3.966 df 19 p <.05), fewer course of oral steroids (t test 3.750 df 18, p <.05), better adherence to therapy (z score -3.272, p <.05), level of control (z score -4.132, p <.001) *not significant, but experienced 4 fewer missed school days (t test 1.928 df 15 p >.05) |

| Wajnberg 2010 | Quasi-experiment | High | Older adults (65+)/ Homebound by Medicare’s definition |

N=179 Mean age: 79.0 (SD10.6) Female 70% Education: not reported Race ethnicity: 49% Black, 26% White, 12% Hispanic, 14% other |

NP makes monthly visits after the primary care physician (PCP) performs an initial comprehensive visit, including continuous assessment, lab evaluation, medication provision/ Monthly (NP), every 3 months (PCP) |

Utilization- hospitalization, nursing home admission [medical and billing records] | Less patients had ≥ 1 hospitalization (pre vs post 61% vs 38%, p <.05), less patients had ≥ 1 nursing home admission (pre vs post 38% vs 18%, p <.05) |

| Zimmer 1985 | Randomized controlled trial | Medium | Adults/ Homebound patients with chronical or terminal illness, or disability |

N=158 intervention (n=82) Mean age: 73.8 Female: 61.0 Mean education: 9.6 (years) Race/ethnicity: white 73.2% Control (n=76) Mean age 77.4 Female: 76.3% Mean education: 8.9 (years) Race/ethnicity: White 85.5% |

One home visit assessment by NP, internist, social worker, 24-hour telephone service for emergency consultation/ Initial, as needed |

Utilization- hospitalization, nursing home admission, ED visits [diary] Health status- [The sickness impact profile] Patient and caretaker morale/life satisfaction [Philadelphia geriatric center moral scale] |

Intervention group spent less days per month in hospital (2.04 vs 3.29, p: not reported) and nursing home (0.55 vs 1.32 p: not reported). More days per month in ED visits ED visits (0.26 vs 0.15 p: not reported). Health status: no difference between intervention and control after controlled for age, sex, and initial health status score in 3 months (55 vs 49) or at 6 months (39 vs 34) Patient morale/life satisfaction: no difference between intervention or control initial (intervention 25.6, control 26.8) or six months (intervention 25.9 control 25.8); no difference across time for intervention (initial 25.6, 6-month 25.9). |

Studies were provider-focused

The mean sample size for studies focused on patients was 542, with a range of 18 (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014) to 2,188 (Muramatsu et al., 2004). Two studies focused on provider perspectives on patient outcomes, with a range of 13 (Jones et al., 2017) to 27 (Muramatsu et al., 2004) providers. Nine studies included more female participants (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Jones et al., 2017; Stuck et al., 1995; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985). One did not report the sex of the participants (Muramatsu et al., 2004). Two studies included veterans (Kobb et al., 2003; Stone et al., 2010). Half of the studies included >50% White participants in the sample (Coppa et al., 2018; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Kobb et al., 2003; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stone et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985); four included >50% racial/ethnic minorities such as Black and Latinx (Counsell et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2017; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010). Three studies did not report the race/ethnicity of the samples (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995).

Most samples were adults (n=12) (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Stone et al., 2010; Stuck et al., 1995; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985). Five of them were specific to older adults (65+) (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Stuck et al., 1995). The most common inclusion criteria was homebound (n=6) (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985). Other inclusion criteria included heart failure (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014), intellectual or developmental disability (Hahn & Aronow, 2005), poverty (Counsell et al., 2007), or uncontrolled diabetes (Stone et al., 2010). Two studies focused on children with special healthcare needs (Palfrey et al., 2004) or asthma (Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019).

DESCRIPTION OF HOME-BASED PRIMARY CARE NP INTERVENTIONS

NPs were the sole home-based healthcare providers in half of the studies (n=7) (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Jones et al., 2017; Stone et al., 2010; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Zimmer et al., 1985). Six studies included NPs and other health professionals in the intervention team, including physicians (Muramatsu et al., 2004; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995), social workers (Kobb et al., 2003), or both (Counsell et al., 2007; Wajnberg et al., 2010). All NPs in the studies performed history-taking, physical examination, medication reconciliation, as well as education (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stone et al., 2010; Stuck et al., 1995; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985). Other common tasks included care coordination (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Palfrey et al., 2004; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Zimmer et al., 1985). NPs in one study helped patients and caregivers to consolidate medical information (Palfrey et al., 2004). Most studies used face-to-face home visits (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Jones et al., 2017; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985). Two studies used telemonitoring and phone calls to connect with participants (Kobb et al., 2003; Stone et al., 2010) (see Table 1).

OUTCOMES OF HOME-BASED PRIMARY CARE NP INTERVENTIONS

The outcomes examined in the included studies are categorized as healthcare utilization, health status, and others. Healthcare utilization such as emergency department (ED)visit or hospitalization was the most common type of outcome reported. A variety of subjective and objective clinical health outcomes, costs, and satisfaction were also reported.

Healthcare utilization:

Healthcare utilization outcomes were used as the main outcomes in all but two studies (n=12) (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985). The most common measure was hospitalization (n=12) (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985), ED visit (n=8) (Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Kobb et al., 2003; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Palfrey et al., 2004; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Zimmer et al., 1985), and nursing home admission (n=3) (Stuck et al., 1995; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985). Utilization outcomes were often captured by health records (n=4) (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Counsell et al., 2007; Kobb et al., 2003; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019), patient- or caregiver-reported questionnaires or diaries (n=3) (Jones et al., 2017; Palfrey et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 1985), both health records and claims (n=2) (Coppa et al., 2018; Wajnberg et al., 2010), provider qualitative interviews or focus groups (n=2) (Dick & Frazier, 2006; Muramatsu et al., 2004), or billing or insurance claims (Stuck et al., 1995).

Ten of twelve studies addressing healthcare utilization found that NP home visits led to fewer hospitalizations (n=10) (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010). The intervention group in the two studies without significant utilization changes had a trend of decreased hospitalizations (Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007). Among eight studies that included an outcome of ED admissions, five reported significantly less ED visits among intervention participants (Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Kobb et al., 2003; Muramatsu et al., 2004); the others (n=3) found no group difference (Palfrey et al., 2004; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Zimmer et al., 1985). All three studies that examined nursing home admissions found fewer nursing home admissions in intervention participants (Stuck et al., 1995; Wajnberg et al., 2010; Zimmer et al., 1985).

Health status:

Ten studies included health status outcomes (Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Kobb et al., 2003; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stone et al., 2010; Stuck et al., 1995; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Zimmer et al., 1985). The health status outcomes encompassed subjective overall health (n=4) (Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 1985), functional status (n=3) (Counsell et al., 2007; Kobb et al., 2003; Stuck et al., 1995), objective health outcomes (i.e., hemoglobin A1c, health risk reduction) (n=2) (Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Stone et al., 2010), self-reported illness measure (Palfrey et al., 2004), or both self-reported symptoms and objective treatment level (Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019). Health status was determined mostly from participant-reported or caregiver-reported data (n=6) (Counsell et al., 2007; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Kobb et al., 2003; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019). To retrieve patient health status, studies utilized medical records (n=2) (Stone et al., 2010; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019) or qualitative data from individual and/or focus group interviews with NPs (n=2) (Dick & Frazier, 2006) or from both NPs and patients (Muramatsu et al., 2004).

Among four studies measured subjective health outcomes, two found no changes (Counsell et al., 2007; Zimmer et al., 1985), but one interviewing patients found better perceived health (Muramatsu et al., 2004), and one found that NPs believed their patients’ quality of life was improved (Dick & Frazier, 2006). Among three studies with a functional status outcome, two reported significant improvement (Kobb et al., 2003; Stuck et al., 1995); the other study found a trend in better functioning though the result was not statistically significant (Counsell et al., 2007). Two studies that measured objective health outcomes found a greater decrease in hemoglobin A1c (Stone et al., 2010) or more health risk reduction among intervention participants (Hahn & Aronow, 2005). Palfrey et al. (2004) found that providing NP home visits to children with special needs significantly improved school and work attendance for children and parents. Finally, one study found that children with asthma had fewer courses of oral steroids, fewer nighttime symptoms, and better asthma control (Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019).

Others:

Five articles reported cost-related outcomes (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Counsell et al., 2009; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995; Zimmer et al., 1985). One article reported cost savings of $200,000 for 18 participants but did not report how they calculated savings (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014). Two articles calculated the potential savings by adding all medical expenses and intervention operation costs (Counsell et al., 2009; Zimmer et al., 1985). One article found that the mean costs per patient in the post-intervention year were significantly less in patients with high risk of hospitalization in the intervention arm than in those in the control arm ($5,088 vs. $6,575, p<.001); however, both mean 2-year total costs ($14,348 vs. $11,834, p>.05) and mean costs per patient in per-intervention year ($5,045 vs. $4,732, p>.05) were not different between groups (Counsell et al., 2009). The other study reported that the mean day-cost differences were not statistically significant between intervention and control groups (Zimmer et al., 1985). Additionally, one article reported total revenue deficits for the intervention but noted it was less than the national average loss per physician ($41,338 vs. $54,721 in 2001) (Muramatsu et al., 2004). Finally, Stuck et al. (1995) reported cost estimates of the NP-intervention ($24,000 per 100 persons) and of preventing one day of stay in a nursing home ($35).

Four articles included outcomes relevant to patients’ or caregivers’ satisfaction with the intervention (Kobb et al., 2003; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stuck et al., 1995; Zimmer et al., 1985). For patient satisfaction, two articles showed that more than 95% of the participants were satisfied with the NP intervention (Kobb et al., 2003; Stuck et al., 1995). Although one study showed no significant difference in patient satisfaction, caregiver satisfaction was significantly higher in the intervention group (99.8 vs 88.8, p<.05) (Zimmer et al., 1985). Another study showed that caregiver satisfaction increased 0.2 points on a 10-point scale post-intervention, though it was not statistically significant (Palfrey et al., 2004).

QUALITY

Table 2 lists the quality ratings for each study. Eleven of 14 studies included in the review were rated as high quality (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Palfrey et al., 2004; Stone et al., 2010; Stuck et al., 1995; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010) and three studies were rated as medium quality (Dick & Frazier, 2006; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Zimmer et al., 1985). Of the 11 high quality studies, three were RCTs (Counsell et al., 2007; Stanhope et al., 2018; Stuck et al., 1995), seven were quasi-experimental (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Palfrey et al., 2004; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010,) and one was qualitative (Dick & Frazier, 2006). Of the three medium quality studies, one was an RCT (Zimmer et al., 1985), one was quasi-experimental (Hahn & Aronow, 2005), and one was qualitative (Muramatsu et al., 2004). Common methodological challenges in the RCTs included participants and interventionists not being blinded to treatment assignment (Counsell et al., 2007; Stone et al., 2010; Stuck et al., 1995; Zimmer et al., 1985); also, allocation was not concealed (Stone et al., 2010; Stuck et al., 1995; Zimmer et al., 1985). Most of the quasi-experimental studies were unclear about the follow-up completion (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010) and did not have a control group (Bryant & Gaspar, 2014; Coppa et al., 2018; Hahn & Aronow, 2005; Palfrey et al., 2004; Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019; Wajnberg et al., 2010). Neither qualitative studies demonstrated congruence between research methodology and analytic methods nor addressed the influence of the researcher on the research (Dick & Frazier, 2006; Muramatsu et al., 2004).

Table 2.

Quality Rating

Quality ratings based on study type (RCT, quasi-experimental, and qualitative)

| Randomized controlled trial | Counsell, 2006, 2007, 2009 | Stone, 2010 | Stuck, 1995 | Zimmer, 1985 | ||||

| Items | ||||||||

| 1. Was true randomization used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 2. Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 3. Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 4. Were participants blind to treatment assignment? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 5. Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 6. Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 7. Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 8. Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed? | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 9. Were participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 10. Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 11. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 12. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 13. Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Total Score | 10 | 9 | 10 | 7 | ||||

| Percentage (%) | 83.3 | 69.2 | 76.9 | 53.8 | ||||

| Quasi-Experimental | Bryant, 2014 | Coppa, 2018 | Hahn, 2005 | Jones, 2017 | Kobb, 2013 | Palfrey, 2004 | Swartz, 2019 | Wajnberg, 2010 |

| Items | ||||||||

| 1. Is it clear in the study what is the ‘cause’ and what is the ‘effect’ (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. Were the participants included in any comparisons similar? | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Was there a control group? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Were there multiple measurements of the outcome both pre and post the intervention/exposure? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed? | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total Score | 6 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Percentage (%) | 75.0 | 77.8 | 55.6 | 88.9 | 66.7 | 77.8 | 77.8 | 77.8 |

| Qualitative | Dick, 2006 | Muramatsu, 2004 | ||||||

| Items | ||||||||

| 1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| 5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice- versa, addressed? | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| 8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpreta- tion, of the data? | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Total Score | 8 | 5 | ||||||

| Percentage (%) | 80 | 50 |

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that provides a critical appraisal of studies on home-based primary care provided by NPs to people across life spans in the U.S. Although there was a great variability in terms of study design, setting, and sample, most of the studies included healthcare utilization outcomes and showed that NP-led home-based primary care improved health utilization. However, there were inconsistent findings for health status outcomes.

We found that participants in NP home-based primary care interventions were more likely to be older and female, have multiple chronic disease diagnoses, and self-identify as White. The sociodemographic characteristics of study samples described in this review reflect the issues of health inequity that are present in health systems across the country (Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). Patients from disadvantage and minority groups often have unmet social needs that should be prioritized in interventions alongside their health needs (Kreuter et al., 2021). Community-based interventions have shown that addressing social needs can reduce avoidable health utilization and improve patient satisfaction (Daaleman et al., 2019; Moreno et al., 2021). As many NP-led home-based interventions have been community-based, they offer an innovative approach improving both social and health needs for marginalized populations.

While prior reviews of studies addressing home-based healthcare revealed healthcare utilization as primary outcomes (Mora et al., 2017; Osakwe et al., 2020; Zimbroff et al., 2021), we found several studies evaluating patient-reported outcomes that included subjective health (Counsell et al., 2007; Dick & Frazier, 2006; Muramatsu et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 1985), functional status (Counsell et al., 2007; Kobb et al., 2003; Stuck et al., 1995), and self-reported symptoms (Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019) with mixed results. Specifically, we noted half of four studies addressing subjective health had improvements but only in the studies using qualitative approaches (Dick & Frazier, 2006; Muramatsu et al., 2004). The effects of NP home visits on functional status and patient symptoms were overall positive, with two of three studies examining functional status (Kobb et al., 2003; Stuck et al., 1995) and one study examining asthma symptoms (Swartz & Meadows-Oliver, 2019) showing significant improvements. Patient-reported outcomes encompass patient-reported disease symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue, anxiety), functional status (e.g., physical, emotional, social functioning), or health- related quality of life (Food and Drug Administration, 2009). With increasing recognition of the importance of patient-centered data in clinical trials, patient-reported outcomes may provide information on the impact of an intervention that is more relevant and meaningful to patients. Future trials should consider incorporating more patient-reported outcomes to ensure that impacts of NP home visit interventions adequately assess patient perspectives.

Caregiver burden is increasing as the population ages and develops more chronic conditions. According to the Family Caregiver Alliance in the United States, as of 2019, there were 41 million informal caregivers providing care, with the approximate cost of their unpaid work of approximately $470 billion (Reinhard et al., 2019). However, our review revealed that the caregiver burden has been understudied. Only two studies have included caregivers’ satisfaction with the intervention (Palfrey et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 1985) and only one assessed the caregivers’ burden (i.e., parental workdays) (Palfrey et al., 2004). Future research is warranted to investigate how NP-led home-based primary care may be beneficial not only to chronically ill, homebound patients but also to their caregivers.

Face-to-face home visits were the most common mode of NP intervention delivery among the included studies. Only two studies used telemonitoring or phone calls to connect with participants with similar outcomes (Kobb et al., 2003; Stone et al., 2010). Telehealth uses electronic information and telecommunication technologies to provide health care remotely (Health Resources & Services Administration, 2020). Integration of home-based primary care and telemonitoring or telehealth have long been tested in rural America (Sorocco et al., 2013). Recent evidence indicates that telehealth addresses some barriers to “in-person” appointments such as transportation, time, and work commitment (Gordon et al., 2020) and decreases the rate of missed appointments (Snoswell & Comans, 2020). Additionally, a home-based primary care team focusing on homebound older adults with multiple comorbidities transitioned their care to telehealth during COVID-19 and found fewer hospitalizations and ED visits during COVID-19 compared to a year prior (Abrashkin et al., 2021). As the adoption of telehealth continues, equity is one area of concern. The digital divide presents a potential barrier and many older adults have faced challenges in adjusting to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kalicki et al., 2021). More research is needed to study the effect on health outcomes using telehealth and the balance between NP home visits and NP telehealth in the setting of home-based primary care.

From an overall quality perspective, the majority of our studies were rated as high quality. Nonetheless, within the sample of quasi-experimental studies, only two of the eight studies (Jones et al., 2017; Kobb et al., 2003) included a control group for comparative purposes. This decreases causal plausibility and reminds us to exercise caution in interpreting the bulk of our findings. Likewise, it is important to note that one of the RCTs (Zimmer et al., 1985) stratified the sample by three variables (hospice/terminal status, cognition, and being a member of a couple where both wanted to be in the study) before randomization, but did not report stratum-specific estimates. Additionally, the limited number of unique studies in this review warrants further confirmatory and innovative research into this important field. Therefore, although these studies were generally carried out with rigor, we must acknowledge the design limitations when synthesizing these research findings.

This systematic review has some limitations. First, it is possible that we did not find all relevant articles in the literature even though we conducted an extensive systematic electronic search in consultation with an experienced health sciences librarian and conducted hand searches of references of the identified studies. We also included only articles conducted in the United States written in English. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to studies outside the United States. In addition, we did not include gray literature such as quality improvement reports from organizations; hence, publication bias may exist. Moreover, the published year of the included ranged from 1985 to 2019. It is likely the role of the NPs in those earlier published studies were limited compared to later published studies as only nine states plus the District of Columbia (D.C.) adopted a long-term full practice authority before 2000 (Brom et al., 2018) while NPs in 24 states plus D.C. have full practice authority in 2021 (American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 2021). The home-based primary care intervention by NPs may have evolved based on this change and trend. We decided to include and report all studies regarding the NP’s roles in home-based primary care intervention given the limited numbers of studies we found. Finally, the studies’ participants included in this review were predominantly female and self-identified as White. This may limit the generalizability of study results. Therefore, the findings from this review should be interpreted with caution.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Home-based primary care programs are designed to meet the needs of patients with complex health needs that are largely underserved by traditional primary care clinical models. Our review of 14 studies of various study designs show that home-based primary care provided by NPs may decrease the consequent health utilization (e.g., hospitalizations, ED visits) but results are mixed with respect to health status and cost-related outcomes. With full practice authorization by the 2020 Federal CARES Act to allow NPs to independently assess, diagnose, and order homecare services, NP-led home-based primary care programs have potential to promote the health status of underserved populations while saving costs. Our findings suggest the need for evaluating home-based primary care led by NPs to more diverse populations with more patient-reported and caregiver outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The study was supported, in part, by grants from the NIH NCATS Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research [UL1TR003098], the National Institute of Nursing Research [P30NR018093], and the National Institute on Aging [R01AG062649] to HRH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional resources were provided by the Center for Community Programs, Innovation, and Scholarship at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/Completing interests – None

Declarations

Ethical Approval – Not applicable

Consent to participate – Not applicable

Availability of data and material – Not applicable

Code availability – Not applicable

Consent for publication– Not applicable

References

- Abrashkin KA, Zhang J, & Poku A (2021). Acute, Post-acute, and Primary Care Utilization in a Home-Based Primary Care Program During COVID-19. The Gerontologist, 61(1), 78–85. 10.1093/geront/gnaa158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Home Care Medicine. (n.d.). What is home-based primary care? American Academy of Home Care Medicine. https://www.aahcm.org/what_is_hbpc [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. (n.d.). Improve Medicare patient access to home health services. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/federal/federal-issue-briefs/improve-medicare-patients-access-to-home-health-care [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. (2021). Practice information by state: What you need to know about NP practice in your state. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. https://www.aanp.org/practice/practice-information-by-state [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association. (2020). Congress Passes and the President Signs into Law Third COVID-19 Package. American Nurses Association. https://anacapitolbeat.org/2020/03/27/congress-passes-and-the-president-signs-into-law-third-covid-19-package [Google Scholar]

- Ankuda CK, Husain M, Bollens-Lund E, Leff B, Ritchie CS, Liu SH, & Ornstein KA (2021). The dynamics of being homebound over time: A prospective study of Medicare beneficiaries, 2012–2018. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 69(6), 1609–1616. 10.1111/jgs.17086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brom HM, Salsberry PJ, & Graham MC (2018). Leveraging health care reform to accelerate nurse practitioner full practice authority. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 30(3), 120–130. 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant R, & Gaspar P (2014). Implementation of a self-care of heart failure program among home-based clients. Geriatric Nursing (New York), 35(3), 188–193. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JE, Lai AY, Gupta A, Nguyen AM, Berry CA, & Shelley DR (2021). Rapid Transition to Telehealth and the Digital Divide: Implications for Primary Care Access and Equity in a Post-COVID Era. The Milbank Quarterly, 99(2), 340–368. 10.1111/1468-0009.12509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppa D, Winchester SB, & Roberts MB (2018). Home-based nurse practitioners demonstrate reductions in rehospitalizations and emergency department visits in a clinically complex patient population through an academic-clinical partnership. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 30(6), 335–343. 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Buttar AB, Clark DO, & Frank KI (2006). Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE): A New Model of Primary Care for Low-Income Seniors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 54(7), 1136–1141. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00791.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, Tu W, Buttar AB, Stump TE, & Ricketts GD (2007). Geriatric Care Management for Low-Income Seniors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 298(22), 2623–2633. 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, Stump TE, & Arling GW (2009). Cost Analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders Care Management Intervention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 57(8), 1420–1426. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02383.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley C, Stuck Amy R., Martinez T, Wittgrove AC, Zeng F, Brennan JJ, Chan TC, Killeen JP, & Castillo Edward M.. (2016). Survey and Chart Review to Estimate Medicare Cost Savings for Home Health as an Alternative to Hospital Admission Following Emergency Department Treatment. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 51(6), 643–647. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.07.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daaleman TP, Ernecoff NC, Kistler CE, Reid A, Reed D, & Hanson LC (2019). The Impact of a Community-Based Serious Illness Care Program on Healthcare Utilization and Patient Care Experience. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(4), 825–830. 10.1111/jgs.15814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge KE, Jamshed N, Gilden D, Kubisiak J, Bruce SR, & Taler G (2014). Effects of Home-Based Primary Care on Medicare Costs in High-Risk Elders. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 62(10), 1825–1831. 10.1111/jgs.12974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick K, & Frazier SC (2006). An exploration of nurse practitioner care to homebound frail elders. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 18(7), 325–334. 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. (2009). Guidance for Industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labelling claims (). https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Franzosa E, Gorbenko K, Brody AA, Leff B, Ritchie CS, Kinosian B, Ornstein KA, & Federman AD (2021). “At Home, with Care”: Lessons from New York City Home-based Primary Care Practices Managing COVID-19. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 69(2), 300–306. 10.1111/jgs.16952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Jaramillo V, Fuhrer V, Gonzalez-Jaramillo N, Kopp-Heim D, Eychmüller S, & Maessen M (2020). Impact of home-based palliative care on health care costs and hospital use: A systematic review. Palliative & Supportive Care, 1–14. 10.1017/S1478951520001315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon HS, Solanki P, Bokhour BG, & Gopal RK (2020). “I’m Not Feeling Like I’m Part of the Conversation” Patients’ Perspectives on Communicating in Clinical Video Telehealth Visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine: JGIM, 35(6), 1751–1758. 10.1007/s11606-020-05673-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JE, & Aronow HU (2005). A Pilot of a Gerontological Advanced Practice Nurse Preventive Intervention. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 18(2), 131–142. 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2005.00242.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources & Services Administration. (2020). Understanding telehealth. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/patients/understanding-telehealth/#what-is-telehealth.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017). Critical Appraisal Tools. https://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical_appraisal_tools

- Jones MG, DeCherrie LV, Meah YS, Hernandez CR, Lee EJ, Skovran DM, Soriano TA, & Ornstein KA (2017). Using Nurse Practitioner Co-Management to Reduce Hospitalizations and Readmissions Within a Home-Based Primary Care Program. Journal for Healthcare Quality, 39(5), 249–258. 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MG, Ornstein KA, Skovran DM, Soriano TA, & DeCherrie LV (2017). Characterizing the high-risk homebound patients in need of nurse practitioner co-management. Geriatric Nursing (New York), 38(3), 213–218. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalicki AV, Moody KA, Franzosa E, Gliatto PM, & Ornstein KA (2021). Barriers to telehealth access among homebound older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 10.1111/jgs.17163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobb R, Hoffman N, Lodge R, & Kline S (2003). Enhancing Elder Chronic Care through Technology and Care Coordination: Report from a Pilot. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 9(2), 189–195. 10.1089/153056203766437525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Thompson T, McQueen A, & Garg R (2021). Addressing Social Needs in Health Care Settings: Evidence, Challenges, and Opportunities for Public Health. Annual review of public health, 42, 329–344. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339(jul21 1), b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monzón-Kenneke M, Chiang P, Yao N (., & Greg M (2021). Pharmacist medication review: An integrated team approach to serve home-based primary care patients. PloS One, 16(5), e0252151. 10.1371/journal.pone.0252151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora K, Dorrejo XM, Carreon KM, & Butt S (2017). Nurse practitioner-led transitional care interventions: An integrative review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29(12), 773–790. 10.1002/2327-6924.12509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno G, Mangione CM, Tseng CH, Weir M, Loza R, Desai L, Grotts J, & Gelb E (2021). Connecting Provider to home: A home-based social intervention program for older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(6), 1627–1637. 10.1111/jgs.17071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu N, Mensah E, & Cornwell T (2004). A Physician House Call Program for the Homebound. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety, 30(5), 266–276. 10.1016/S1549-3741(04)30029-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GJ, Wade AJ, Morris AM, & Slaboda JC (2018). Home and community-based services coordination for homebound older adults in home-based primary care. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 241. 10.1186/s12877-018-0931-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong HL, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Sambasivam R, Fauziana R, Tan M, Chong SA, Goveas RR, Chiam PC, & Subramaniam M (2018). Resilience and burden in caregivers of older adults: moderating and mediating effects of perceived social support. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 27. 10.1186/s12888-018-1616-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osakwe ZT, Aliyu S, Sosina OA, & Poghosyan L (2020). The outcomes of nurse practitioner (NP)-Provided home visits: A systematic review. Geriatric Nursing (New York), 41(6), 962–969. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey JS, Sofis LA, Davidson EJ, Liu J, Freeman L, & Ganz ML (2004). The Pediatric Alliance for Coordinated Care: evaluation of a medical home model. Pediatrics (Evanston), 113(5 Suppl), 1507–1516. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15121919 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard SC, Feinberg LF, Houser A, Choula R, & Evans M (2019). Valuing the Invaluable: 2019 Update. (). Washington DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. 10.26419/ppi.00082.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchman M, Fain M, & Cornwell T (2018). The Resurgence of Home-Based Primary Care Models in the United States. Geriatrics (Basel), 3(3), 41. 10.3390/geriatrics3030041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snoswell CL, & Comans TA (2020). Does the Choice Between a Telehealth and an In-Person Appointment Change Patient Attendance? Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 10.1089/tmj.2020.0176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorocco KH, Bratkovich KL, Wingo R, Qureshi SM, & Mason PJ (2013). Integrating Care Coordination Home Telehealth and Home Based Primary Care in Rural Oklahoma. Psychological Services, 10(3), 350–352. 10.1037/a0032785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope SA, Cooley MC, Ellington LF, Gadbois GP, Richardson AL, Zeddes TC, & LaBine JP (2018). The effects of home-based primary care on Medicare costs at Spectrum Health/Priority Health (Grand Rapids, MI, USA) from 2012-present: a matched cohort study. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 161. 10.1186/s12913-018-2965-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone RA, Rao RH, Sevick MA, Cheng C, Hough LJ, Macpherson DS, Franko CM, Anglin RA, Obrosky DS, & Derubertis FR (2010). Active Care Management Supported by Home Telemonitoring in Veterans With Type 2 Diabetes: The DiaTel randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 33(3), 478–484. 10.2337/dc09-1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuck AE, Aronow HU, Steiner A, Alessi CA, Bula CJ, Gold MN, Yuhas KE, Nisenbaum R, Rubenstein LZ, & Beck JC (1995). A Trial of Annual in-Home Comprehensive Geriatric Assessments for Elderly People Living in the Community. The New England Journal of Medicine, 333(18), 1184–1189. 10.1056/NEJM199511023331805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz MK, & Meadows-Oliver M (2019). Clinical Outcomes of a Pediatric Asthma Outreach Program. Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 15(6), e119–e121. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2019.01.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). MeSH—House calls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/68006792

- Valluru G, Yudin J, Patterson CL, Kubisiak J, Boling P, Taler G, De Jonge KE, Touzell S, Danish A, Ornstein K, & Kinosian B (2019). Integrated Home- and Community-Based Services Improve Community Survival Among Independence at Home Medicare Beneficiaries Without Increasing Medicaid Costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 67(7), 1495–1501. 10.1111/jgs.15968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajnberg A, Wang KH, Aniff M, & Kunins HV (2010). Hospitalizations and Skilled Nursing Facility Admissions Before and After the Implementation of a Home-Based Primary Care Program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 58(6), 1144–1147. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02859.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff-Baker D, & Ordona RB (2019). The Expanding Role of Nurse Practitioners in Home-Based Primary Care: Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 45(6), 9–14. 10.3928/00989134-20190422-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao N, Rose K, LeBaron V, Camacho F, & Boling P (2017). Increasing Role of Nurse Practitioners in House Call Programs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 65(4), 847–852. 10.1111/jgs.14698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimbroff RM, Ornstein KA, & Sheehan OC (2021). Home-based primary care: A systematic review of the literature, 2010–2020. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 10.1111/jgs.17365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer JG, Groth-Juncker A, & McCusker J (1985). A randomized controlled study of a home health care team. American Journal of Public Health (1971), 75(2), 134–141. 10.2105/ajph.75.2.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.