Abstract

In this study, Norwalk-like virus (NLV) RNA was detected by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) in sewage water concentrates. Sequence analysis of the RT-PCR products revealed identical sequences in stools of patients and related sewage samples. In 6 of 11 outbreak-unrelated follow-up samples, multiple NLV genotypes were present. Levels as high as 107 RNA-containing particles per liter were found. These data show that high loads of NLVs may be present in sewage and warrant further studies addressing the efficacy of NLV removal by sewage water treatment processes.

The most common viral pathogens associated with epidemic gastroenteritis in adults are the Norwalk-like caliciviruses (NLVs), also known as small round-structured viruses. NLVs have been implicated in numerous food-borne and waterborne outbreaks (7). Outbreaks of NLV have been associated with drinking fecally contaminated water (8, 11, 22) and with swimming in contaminated recreational water (9). Until now, routine microbiological quality control of such surface waters is performed by the enumeration of fecal coliform bacteria, and occasionally water samples are also screened for the presence of enteroviruses. However, it is clear that there is no correlation between the levels of fecal bacteria and those of viruses that cause gastroenteritis (12). Therefore, it would be better to screen waters also for specific, known pathogens. Based on such screening, waters could be concluded as being safe or not with respect to those pathogens tested.

Recently, sensitive reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR)-based detection methods have been developed and used to determine the presence of NLVs or other enteric viruses in sewage and surface water (1, 3–5, 13, 16, 17). However, few groups have addressed the use of these assays in field surveys (1, 3, 5, and 17). To validate the methods used during periods of known sewage contamination, we chose to start monitoring sewage samples in conjunction with outbreaks of viral gastroenteritis, epidemiologically linked with NLVs. The outbreaks occurred in November 1997, December 1997, and March 1998 in nursing homes in the cities of Reeuwijk, Apeldoorn, and Enkhuizen, The Netherlands, respectively. Stool specimens were collected from persons with (patients) and without (controls) reported illness. From each outbreak, at least five stool samples from patients were tested for the presence of Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and Shigella spp. by routine culture and for the presence of group A rotavirus, adenovirus types 40/41, and astrovirus by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (rotavirus, adenovirus, astrovirus) or NLV RT-PCR (NLV) (21). More than 50% of the stool samples from patients from the three outbreaks tested positive for NLV.

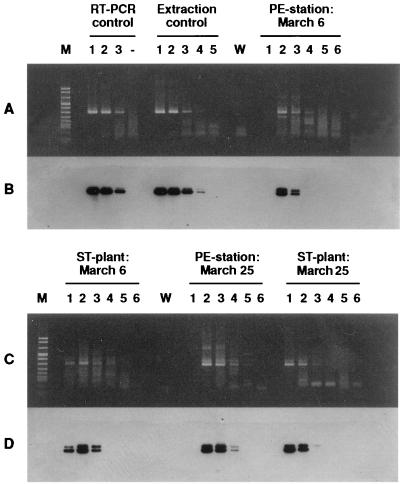

The sewage samples were all taken close to the source of the outbreak, where high concentrations of NLVs could be expected. In addition, in the period from February to May 1998, at one of the locations (Apeldoorn), a follow-up survey at 3-week intervals was done at the pumping-engine station and the nearby sewage treatment plant (treating sewage from 140,000 inhabitant equivalents). Raw sewage samples (10 liters each) were first concentrated by a conventional filter adsorption-elution method (19). The resulting eluate (650 ml) was used in a two-phase separation method (15) which is based on the selective distribution of viruses in two incompatible phases (Dextran T40 and 10% [wt/vol] polyethylene glycol 6000). We modified this method by omitting the chloroform extraction prior to separation. In our hands, this method gives the highest recovery and reproducibility in comparison to other methods (14). After separation, the bottom phase and the interphase were harvested. Further purification was done by spin column gel chromatography using Sephadex G200 and by ultrafiltration in a Centricon 100 microconcentrator. The resulting RNA extracts were processed by the method of Boom et al. (2), modified to allow an increased input volume by adding solid guanidinium (iso)thiocyanate. Purified viral RNA was subsequently tested in the NLV RT-PCR (21) as well as in a rotavirus group A RT-PCR (6). The detection limit of both assays was determined to be 10 to 100 RNA-containing particles. All negative control samples that had been tested in parallel to monitor for contamination remained negative. Positive control samples, artificially spiked with NLVs of a known genetic cluster, showed a single 326-bp fragment after both RT-PCR and Southern hybridization (Fig. 1A and B). NLV RNA could be detected in sewage samples that had been collected just after notification of the outbreaks at all three locations.

FIG. 1.

RT-PCR detection and Southern hybridization of follow-up sewage samples collected at a pumping engine (PE) station and a sewage treatment (ST) plant in Apeldoorn. (A and C) Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels; (B and D) Southern blot hybridizations corresponding to panels A and C. (A and B) Lane M, molecular weight marker (marker V; Boehringer Mannheim). RT-PCR control lanes include RT-PCR product amplified from undiluted RNA (lane 1), 10-fold-diluted RNA (lane 2), and 100-fold-diluted RNA (lane 3) extracted from an electron microscopy-positive fecal sample. Lane −, negative control. Extraction control lanes include RT-PCR product amplified from undiluted RNA (lane 1), 10-fold-diluted RNA (lane 2), 100-fold-diluted RNA (lane 3), 1,000-fold-diluted RNA (lane 4), and 10,000-fold-diluted RNA (lane 5) from an NLV-positive fecal sample (RT-PCR control) but isolated with the modified method of Boom et al. (2). Lane W, water sample, i.e., negative control. PE-station: March 6 lanes include RT-PCR products amplified from serially diluted RNA, i.e., undiluted (lane 1), 10−1 diluted (lane 2), 10−1 diluted (lane 3), 10−3 diluted (lane 4), 10−4 diluted (lane 5), and 10−5 diluted (lane 6). RNA had been extracted from a sewage sample taken at the PE station on March 6 in Apeldoorn. (C and D) ST-plant: March 6 lanes include lanes such as those described for PE station, March 6 but RNA was extracted from a sewage sample collected at the ST plant, March 6, in Apeldoorn. PE-station: March 25 lanes include serially diluted RNA extracted from sewage sample collected at the PE station, March 25, in Apeldoorn. ST-plant: March 25 lanes include serially diluted RNA extracted from sewage sample collected at the ST plant, March 25, in Apeldoorn.

To determine the viral load, serial sewage extracts collected within 10 days after the first day of illness at the locations of Reeuwijk, Apeldoorn, and Enkhuizen were tested in the NLV RT-PCR assay. RNA dilutions of 10−3, 10−1, and 10−7 were positive as visualized by ethidium bromide staining of agarose gels (Table 1). Of note, in the 10−1 dilutions of some samples that were positive in higher dilutions, no NLV RNA could be amplified, clearly demonstrating that not all PCR inhibitors had been removed (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Detection of NLV and rotavirus RNA by RT-PCR in sewage samples collected during three nursing home outbreaks of NLV gastroenteritis in Reeuwijk, Apeldoorn, and Enkhuizen and in follow-up sewage samples collected at two locations in Apeldoorn in winter and early spring

| Locationa | Date of sampling (day/mo/yr) | First day of illness (day/mo/yr) | % Of samples affected | Positive dilution in RT-PCR

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLV | Rotavirus | ||||

| Reeuwijk | 18/11/97 | 13/11/97 | 67 | 10−4 | 10−2 |

| 11/2/98 | 13/11/97 | —b | 10−3 | ||

| Apeldoorn | 10/12/97 | 4/12/97 | 48 | 10−1 | 10−2 |

| 11/12/97 | 4/12/97 | 100 | 10−1 | ||

| 12/12/97 | 4/12/97 | — | 10−4 | ||

| 16/12/97 | 4/12/97 | 100 | 10−1 | ||

| 12/2/98 | 4/12/97 | — | 10−3 | ||

| Enkhuizen | 1/4/98 | 22/3/98 | 45 | 10−7 | — |

| 2/4/98 | 22/3/98 | 10−6 | — | ||

| 6/4/98 | 22/3/98 | 10−6 | — | ||

| Apeldoorn | |||||

| PE station | 11/2/98 | — | 10−3 | ||

| PE station | 6/3/98 | 10−3 | 10−2 | ||

| PE station | 25/3/98 | 10−4 | 10−2 | ||

| PE station | 15/4/98 | 10−3 | — | ||

| PE station | 6/5/98 | 10−1 | 100 | ||

| PE station | 27/5/98 | 10−1 | — | ||

| ST plant | 6/3/98 | 10−3 | 10−2 | ||

| ST plant | 25/3/98 | 10−2 | — | ||

| ST plant | 15/4/98 | 10−3 | 10−2 | ||

| ST plant | 6/5/98 | 10−1 | 10−2 | ||

| ST plant | 27/5/98 | 10−2 | — | ||

PE, pumping engine; ST, sewage treatment.

—, not detected.

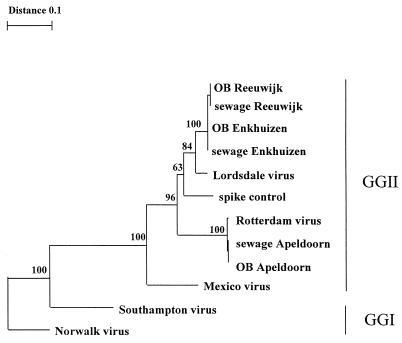

The genetic variability of NLV strains from stool and sewage samples was determined by sequencing the RT-PCR products with the Big Dye terminator kit either directly or after cloning (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk a/d IJssel, The Netherlands). We analyzed DNA sequences of which 145 nucleotides was used to create an alignment and phylogenetic tree by use of Geneworks (V2.5; Intelligenetics, Mountain View, Calif.) and the Treecon software package (18). Strains from stool and sewage were identical for each individual outbreak (Fig. 2). Outbreak strains found in Reeuwijk and Enkhuizen were closely related to the Lordsdale-Bristol cluster within genogroup II of NLVs (20). The viruses found in the Apeldoorn outbreak belong to a different genotype within genogroup II, first detected in The Netherlands in stool samples from an outbreak that occurred in early 1997 in Rotterdam (Fig. 2). This Rotterdam genotype was detected in all three sewage samples collected during the Apeldoorn outbreak.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on a 145-bp region of the RNA polymerase gene showing the relationships among NLVs from genogroup I (GGI) (Norwalk virus and Southampton virus), genogroup II (GGII) (Lordsdale virus, Mexico virus, and Rotterdam virus), and outbreak strains (OB) detected in stool specimens of patients and outbreak-related sewage samples. GenBank accession numbers of the prototype strains were as follows: Norwalk virus, M87661; Southampton virus, L070418; Lordsdale virus, X86557; Mexico virus, U22498. The TREECON program was used to generate the dendrogram (18). Bootstrap values of the internal nodes are indicated.

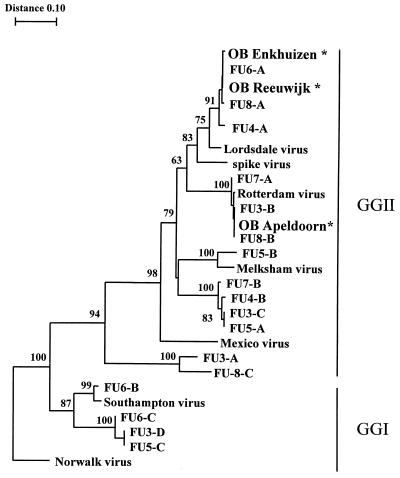

NLVs could also be detected in the follow-up samples taken at the pumping-engine station and the sewage treatment plant. In Apeldoorn, 10 of 11 samples taken were found positive for NLVs, in some samples even up to 10−7 dilutions (Table 1). However, not each NLV RT-PCR product resulted in a clear 326-bp band (Fig. 1A and B). Since we assumed that more strains might cocirculate and therefore be present in a single sewage sample, we cloned the PCR products and sequenced at least five individual clones. By this approach, several additional genotypes were detected in 6 of the 11 specimens for which individual clones were obtained (Fig. 3). Both genogroup I and genogroup II NLVs were found.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on a 145-bp region of the polymerase gene showing the relationships among the three outbreak strains (OB Apeldoorn, OB Reeuwijk, and OB Enkhuizen) indicated by an asterisk and the strains found in follow-up (FU) sewage samples (FU3, FU4, FU5, FU6, FU7, and FU8), Rotterdam virus, and prototype NLVs (Norwalk virus, Southampton virus, Mexico virus, Melksham virus [accession no. X81879], and Lordsdale virus). For the follow-up samples, PCR products were cloned and five different clones were sequenced. Different sequences within a sample were given an alphabetical code (FU3-A, FU3-B, etc.). Bootstrap values of the internal nodes are indicated.

For reference, we also screened for rotaviruses by RT-PCR (6), since the incidence of rotavirus infection in the general population in the Netherlands has been estimated from a population-based survey and from laboratory surveillance data (10). During the peak shedding of rotavirus (between weeks 4 and 12), all sewage samples were found positive for rotavirus but at maximum concentrations that were on average 10-fold lower than those for NLVs (Table 1, Apeldoorn data). Taking into account that NLVs are generally shed at lower maximal titers than rotavirus (7), our data suggest that NLVs may exceed rotaviruses in importance as a cause of illness.

In addition, this study shows that the concentration and purification method described is applicable for virus detection by RT-PCR in water samples. We found that during the study period, the NLV load in sewage was high independent of outbreaks. In future research, the presence of NLVs in surface, recreational, and drinking water, as well as the effectiveness of sewage treatment processes for removal of viral pathogens, will have to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and the Environment (The Netherlands), and KIWA Research and Consultancy (project no. 289202 Water Microbiology).

We thank A. Koks, A. Keja, and F. Slijkerman, from the regional health services Gouda, Apeldoorn, and Hoorn, The Netherlands, respectively, for epidemiological investigations and collection of stool specimens. We also thank the microbiologists participating in the laboratory surveillance network, as well as the Society for Clinical Virology, for supplying data on rotavirus detection. Furthermore, we thank the employees of the sewage treatment plant in Apeldoorn and Olaf E. M. Nijst and Petra M. de Bree for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beller M, Ellis A, Lee S H, Drebot M A, Jenkerson S A, Funk E, Sobsey M D, Simmons O D, Monroe S S, Ando T, Noel J, Petric M, Middaugh J P, Spika J S. Outbreak of viral gastroenteritis due to a contaminated well. JAMA. 1997;278:563–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boom R, Sol C J A, Salimans M M M, Jansen C L, Wertheim-van Dillen P M E, van der Noorda J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubois E, Le Guyader F, Haugarreau L, Kopecka H, Cormier M, Pommepuy M. Molecular epidemiological survey of rotaviruses in sewage by reverse transcriptase seminested PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism assay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1–7. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1794-1800.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gajardo R, Pintó M, Bosch A. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus in environmental samples. Water Sci Technol. 1995;31:371–374. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilgen M, Germann D, Lüthy J, Hübner P. Three-step isolation method for sensitive detection of enterovirus, rotavirus, hepatitis A virus, and small round structured viruses in water samples. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;37:189–199. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(97)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husain M, Seth P, Broor S. Detection of group A rotavirus by reverse transcriptase and polymerase chain reaction in faeces from children with acute gastroenteritis. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1225–1233. doi: 10.1007/BF01322748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapikian A Z, Estes M K, Chanock R M. Norwalk group of viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 783–810. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan J E, Goodman R A, Schonberger L B, Lippy E C, Gary G W. Gastroenteritis due to Norwalk virus: an outbreak associated with municipal water system. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:190–197. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kappus K D, Marks J S, Holman R C, Bryant J K, Baker C, Gary G W, Greenberg H B. An outbreak of Norwalk gastroenteritis associated with swimming in a pool and secondary person-to-person transmission. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;116:834–839. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koopmans M P G, van Asperen I. Epidemiology of rotavirus in The Netherlands. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1999;88(426):31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb14323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson H W, Brayn M M, Glass R I M, Stine S W, Monroe S S, Atrah H K, Lee L E, Englander S J. Waterborne outbreak of Norwalk virus gastroenteritis at a Southwest U.S. resort: role of geological formations in contamination of well water. Lancet. 1991;337:1200–1204. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Guyader F, Dubois E, Menard D, Pommepuy M. Detection of hepatitis A virus, rotavirus, and enterovirus in naturally contaminated shellfish and sediment by reverse transcription-seminested PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3665–3671. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3665-3671.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehnert D U, Stewien K E, Hársi C M, Queiroz A P S, Candeias J M G, Candeias J A N. Detection of rotavirus in sewage and creek water: efficiency of the concentration method. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:97–100. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulders M N, Koopmans M P G, Lodder W, van der Avoort H G A M, van Loon A M. Molecular tools in support of the global polio eradication campaign, chapter 9. Studies on the development of improved methods for the detection of poliovirus in environmental samples. Ph.D. thesis. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: University of Amsterdam; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pöyry T, Stenvik M, Hovi T. Viruses in sewage waters during and after poliomyelitis outbreak and subsequent nation-wide oral poliovirus vaccination campaign in Finland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:371–374. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.371-374.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwab K J, de Leon R, Sobsey M D. Concentration and purification of beef extract mock eluates from water samples for the detection of enteroviruses, hepatitis A virus, and Norwalk virus by reverse transcription-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:531–537. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.531-537.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai Y-L, Tran B, Sangermano L R, Palmer C J. Detection of poliovirus, hepatitis A virus, and rotavirus from sewage and ocean water by triplex reverse transcriptase PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2400–2407. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2400-2407.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Peer Y, De Wachter R. TREECON for Windows: a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the Microsoft Windows environment. Comput Applic Biosci. 1994;10:569–570. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Olphen M, Kapsenberg J G, van de Baan E, Kroon W A. Removal of enteric viruses from surface water at eight waterworks in The Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:927–932. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.5.927-932.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinjé J, Koopmans M P G. Molecular detection and epidemiology of small round-structured viruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in The Netherlands. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:610–615. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinjé J, Altena S A, Koopmans M P G. The incidence and genetic variability of small round-structured viruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in The Netherlands. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1374–1378. doi: 10.1086/517325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson R, Anderson L J, Holman R C, Gary G W, Greenberg H B. Waterborne gastroenteritis due to the Norwalk agent: clinical epidemiologic investigation. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:72–74. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]